Published online Dec 27, 2012. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i12.301

Revised: December 13, 2012

Accepted: December 23, 2013

Published online: December 27, 2012

Processing time: 126 Days and 17.8 Hours

Patients with type 4 gastric cancer and peritoneal metastasis respond better to chemotherapy than surgery. In particular, patients without gastric stenosis who can consume a meal usually experience better quality of life (QOL). However, some patients with unsuccessful chemotherapy are unable to consume a meal because of gastric stenosis and obstruction. These patients ultimately require salvage surgery to enable them to consume food normally. We evaluated the outcomes of salvage total gastrectomy after chemotherapy in four patients with gastric stenosis. We determined clinical outcomes of four patients who underwent total gastrectomy as salvage surgery. Outcomes were time from chemotherapy to death and QOL, which was assessed using the Support Team Assessment Schedule-Japanese version (STAS-J). Three of the patients received combination chemotherapy [tegafur, gimestat and otastat potassium (TS-1); cisplatin]. Two of these patients underwent salvage chemotherapy after 12 and 4 mo of chemotherapy. Following surgery, they could consume food adequately and their STAS-J scores improved, so their treatments were continued. The third patient underwent salvage surgery after 7 mo of chemotherapy. This patient was unable to consume food adequately after surgery and developed surgical complications. His clinical outcomes at 3 mo were very poor. The fourth patient received combination chemotherapy (TS-1 and irinotecan hydrochloride) for 6 mo and then underwent received salvage surgery. After surgery, he could consume food adequately and his STAS-J score improved, so his treatment was continued. After the surgery, he enjoyed his life for 16 mo. Of four patients who received salvage total gastrectomy after unsuccessful chemotherapy, the QOL improved in three patients, but not in the other patient. Salvage surgery improves QOL in most patients, but some patients develop surgical complications that prevent improvements in QOL. If salvage surgery is indicated, the surgeon and/or oncologist must provide the patient with a clear explanation of the purpose of surgery, as well as the possible risks and benefits to allow the patient to reach an informed decision on whether to consent to the procedure.

- Citation: Hashimoto T, Usuba O, Toyono M, Nasu I, Takeda M, Suzuki M, Endou T. Evaluation of salvage surgery for type 4 gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4(12): 301-305

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v4/i12/301.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v4.i12.301

Patients with type 4 gastric cancer generally have a worse prognosis compared with patients with other types of advanced gastric cancer. This is primarily because of the high incidence of peritoneal metastasis in type 4 gastric cancer, which causes intestinal obstruction, hydronephrosis, or obstructive jaundice. Surgical treatment is often only palliative, and systematic chemotherapy is usually essential important to prolong survival[1-3]. In particular, patients who can consume food without gastric or intestinal obstruction often report better quality of life (QOL) during systemic chemotherapy. For gastric cancer, systemic chemotherapy with tegafur, gimestat and otastat potassium (TS-1) achieved higher response rates than conventional 5-flurouridine (5-FU)-based regimens in patients with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Additionally, TS-1 alone or in combination with cisplatin, paclitaxel, or irinotecan, for example, achieved greater antitumor effects and longer survival time for gastric linitis plastica compared with conventional 5-FU regimens[1-3].

For esophageal cancer, salvage surgery is the only curative treatment option after definitive chemoradiotherapy[4]. By contrast, in gastric cancer treatment, if neoadjuvant chemotherapy is effective for primary non-curative gastric cancer, salvage surgery may be performed to evaluate the pathological outcomes. Outcomes of interest in previous studies were procedure-related morbidity, mortality, and survival, but not QOL[5]. It is important to evaluate the outcomes of non-curative surgery, and to understand the potential risks and benefits of non-curative surgery in patients with type 4 gastric cancer. This is particularly true for patients with unsuccessful chemotherapy who cannot adequately consume food because of gastric and intestinal obstruction. Such patients often require salvage surgery to allow them to consume food adequately. Here, we examined the impact of salvage surgery on QOL in four patients who were unsuccessfully treated with chemotherapy.

We identified four patients who could not consume food because of gastric stenosis and obstruction that occurred sometime after starting systemic chemotherapy. The patients were given information about the risk and benefit of salvage surgery, and underwent this procedure.

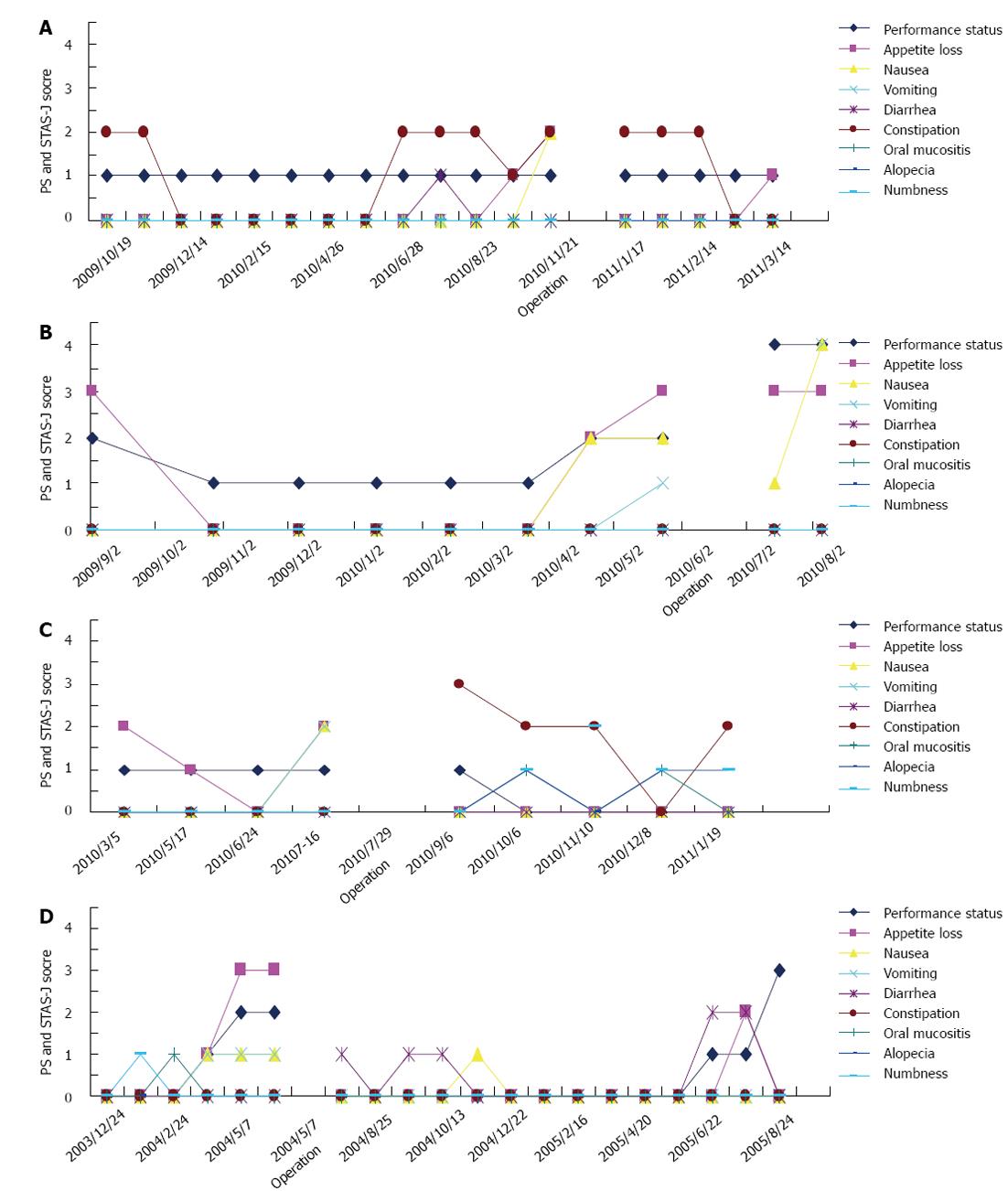

The relationship between QOL and salvage surgery was analyzed. We evaluated QOL during chemotherapy, from the first cycle of chemotherapy until death, using the Support Team Assessment Schedule-Japanese version (STAS-J). The STAS-J records performance status, appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, oral mucositis, alopecia, and numbness, to provide outcome measures assessing quality of palliative care. Each item and the need for improvement is scored on a 5-point (0-4) scale, where high scores indicate many problems and low scores indicate few problems. For example, a score of 0 indicates no symptoms. A score of 1 indicates an occasional or minor single symptom that the patient does not think needs to be resolved. A score of 2 indicates moderate distress, occasional bad days, and symptoms limiting some activities within the extent of the disease. A score of 3 indicates a severe symptom that is often present and greatly affects the patient’s activities and concentration. A score of 4 indicates a severe and continuous overwhelming symptom that prevents the patient from thinking of other things[6-8].

Three patients received TS-1 and cisplatin combination chemotherapy (Cases 1-3) and one received TS-1 and irinotecan combination chemotherapy (Case 4).

Case 1: This was a 68-year-old man. After 12 mo of chemotherapy, the patient was diagnosed with gastric stenosis caused by type 4 gastric cancer. His STAS-J scores for appetite loss and nausea increased because of gastric stenosis, indicating worsening of QOL (Figure 1A). Therefore, the patient underwent salvage surgery to improve his QOL. After salvage surgery, the patient could consume food adequately and his STAS-J scores improved. Chemotherapy was continued for a further 6 mo (Table 1 and Figure 1A).

| Three cases: Chemotherapy (TS-1 and CDDP) |

| Case 1: Salvage surgery was performed after chemotherapy about 12 mo, he could take a meal and improved QOL about 6 mo |

| Case 2: Salvage surgery was performed after chemotherapy about 7 mo, but he could not take a meal and improved QOL |

| Case 3: Salvage surgery was performed after chemotherapy about 4 mo, he could take a meal and improved QOL about 8 mo |

| One case: Chemotherapy (TS-1and CPT11) |

| Case 4: Salvage surgery was performed after chemotherapy about 6 mo, he could take a meal and improved QOL about 16 mo |

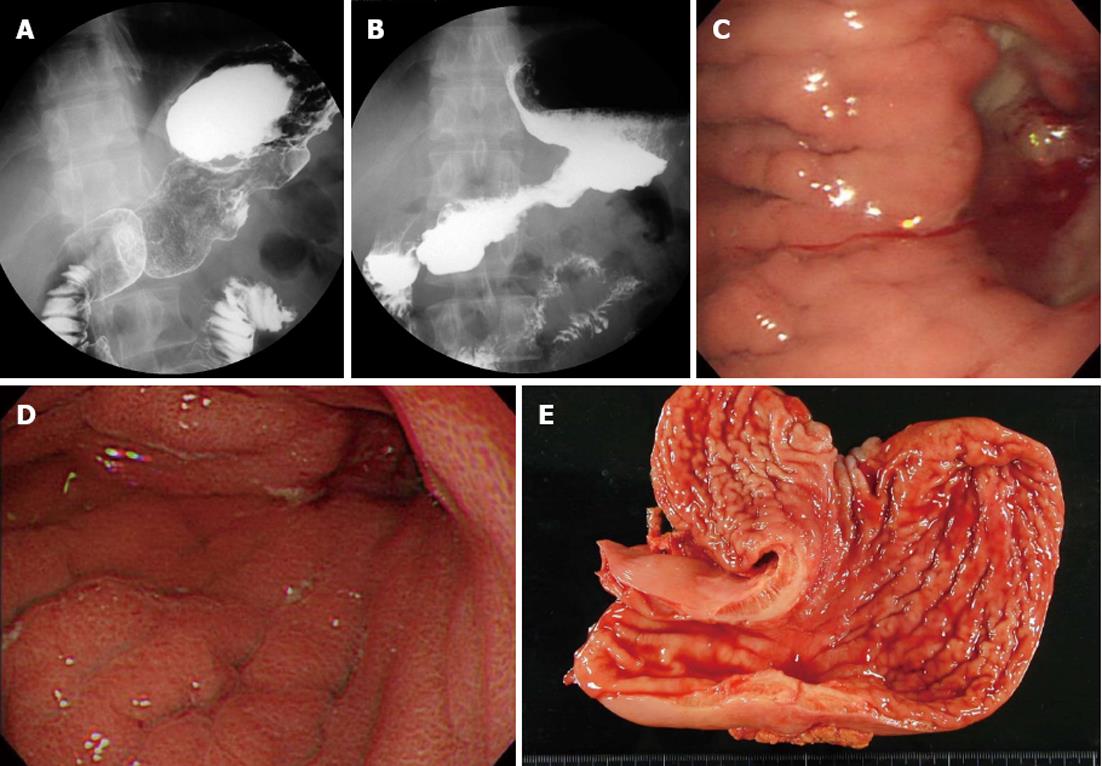

Case 2: This was a 61-year-old man. This patient had gastric stenosis caused by type 4 gastric cancer before starting neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 2A). However, as he could consume food adequately, he received combination chemotherapy. After 7 mo of chemotherapy, his gastric stenosis deteriorated (Figure 2B), which resulted in increases in STAS-J scores for appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, and performance status, thus worsening his QOL (Figure 1B). Therefore, this patient underwent total gastrectomy. However, this patient developed surgical complications and was unable to consume food adequately. The patient had a poor clinical course and died 3 mo after surgery (Table 1 and Figure 1B).

Case 3: This was a 69-year-old man. After 4 mo of chemotherapy, the patient was diagnosed with gastric stenosis caused by type 4 gastric cancer. His STAS-J scores for appetite loss and nausea increased, and his QOL worsened (Figure 3C). Therefore, the patient underwent total gastrectomy. After salvage surgery, his STAS-J scores improved and chemotherapy was continued for a further 8 mo (Table 1 and Figure 1C).

Case 4: This was a 30-year-old man who received TS-1 and irinotecan combination chemotherapy (Figure 3A and C) After 6 mo of chemotherapy, he was diagnosed with gastric stenosis caused by type 4 gastric cancer (Figure 3B and D). His STAS-J scores for appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, and performance status increased and his QOL worsened because of the gastric stenosis (Figure 1D). Therefore, the patient underwent salvage surgery. After surgery, the patient could consume food adequately and his STAS-J scores improved, so chemotherapy was continued. He enjoyed a good life for 16 mo (Table 1 and Figure 1D).

According to the S-1 plus cisplatin vs S-1 in randomized controlled trial in the treatment for stomach cancer (SPIRITS) trial the median overall survival (OS) was significantly longer in patients treated with S-1 plus cisplatin [13.0 mo (range: 7.6-21.9 mo)] than in those treated with S-1 alone (11.0 mo; 95% CI: 5.6-19.8 mo; hazard ratio for death, 0.77; 95% CI: 0.61-0.98; P = 0.04). Progression-free survival (PFS) was also significantly longer in patients treated with S-1 plus cisplatin than in those treated with S-1 alone [median PFS: 6.0 mo (range: 3.3-12.9 mo) vs 4.0 mo (range: 2.1-6.8 mo); P < 0.0001]. The PFS for cases 1, 2, 3 and 4 was approximately 12, 7, 4 and 6 mo, respectively, with a range of 3.3-12.9 mo, while the survival times were approximately 18, 10, 12 and 22 mo, respectively. Thus, the survival time of these patients was within the range reported in the SPIRITS trial, and the OS of our patients was not inferior to that in the SPIRITS trial. Unfortunately, effects of these treatments on QOL were not reported in the SPIRITS trial, so we cannot compare QOL outcomes between our patients and those included in the SPIRITS trial[9].

Symptom relief should be the primary focus of palliative treatment, as recommended by the World Health Organization. Evaluating the effectiveness of palliative interventions should incorporate this goal and include QOL outcome assessments. We have found no articles reporting true QOL outcomes using reliable, validated QOL instruments in surgically managed patients with advanced gastric cancer[10,11]. The STAS includes items that assess the quality of palliative care. This instrument has been used in a variety of clinical fields to evaluate the quality of care or interventions, assess the prevalence of symptoms, and implement outcome measures in clinical practice. Here, we used the STAS-J to evaluate the effects of salvage surgery in patients with type 4 gastric cancer on performance status, appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, oral mucositis, alopecia, and numbness[6-8]. Type 4 gastric cancer often spreads from the upper to the lower body of the stomach through the submucosa, muscularis propria, and subserosa. Although gastro-jejunostomy is often performed to allow patients with type 4 gastric cancer and gastric stenosis or obstruction to consume food, it does not necessarily improve QOL. It is necessary to assess the impact of enteral nutrition caused by jejunostomy with that of salvage total gastrectomy on QOL. Surgical procedures, including total gastrectomy, gastro-jejunostomy, and jejunostomy, are associated with greater risk of complications than other medical assessments. Therefore, surgical management, including total gastrectomy, should be performed for patients in expectation of prolonged survival. Total gastrectomy as salvage surgery carries much greater risk than other palliative surgical procedures. Nevertheless, the QOL of three patients (Cases 1, 3 and 4) improved following salvage surgery. However, Case 2 did not experience an improvement in QOL; this patient had severe gastric stenosis and a greater number of peritoneal metastases compared with the other patients, and was unable to consume food after salvage surgery. It is difficult to improve the QOL of patients with severe stenosis and peritoneal metastasis the around stomach. Consequently, it is necessary to evaluate the risks and benefits of such salvage therapy, and it is essential that the patient is given an adequate description of the purpose of the surgery and the possible risks and benefits. Salvage surgery should only be performed once the patient has given appropriate consent.

There are few reports describing the QOL of surgically managed patients with gastric cancer. Such patients exhibit various clinical states, including peritoneal metastasis grade, presence/absence of invasion to adjacent structures, and general clinical conditions. In additional, the limitations and quality of salvage surgery differ substantially among hospitals. Therefore, it is difficult to precisely evaluate the impact of salvage surgery. Prospectively designed studies using credible QOL instruments are necessary to provide information with better information about the treatment and its outcomes, and thus facilitate the decision-making process.

Of four patients who underwent salvage total gastrectomy following unsuccessful chemotherapy, QOL improved in three but not in one. Salvage surgery can improve the QOL of most patients, but surgical complication and other issues may prevent improvements in QOL. Once indicated, it is essential that the oncologist/surgeon provides the patient with a detailed description of the purpose of surgery, as well as its potential risks and benefits, to allow the patient to reach an informed decision on whether to undergo salvage surgery.

Peer reviewer: Ali Kabir, MD,Nikan Health Researchers Institute, Tehran Hepatitis Center, No. 92, Vesal Shirazi Ave., PO Box 14155/3651, Tehran 15614, Iran

S- Editor Jiang L L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Sasaki T, Koizumi W, Higuchi K, Ishido K, Ae T, Nakatani K, Katada C, Tanabe S, Saigenji K. [Therapeutic strategy for type 4 gastric cancer from the clinical oncologist standpoint]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2007;34:988-992. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Shirao K, Doi T, Sawaki A, Koizumi W, Saito H, Yamaguchi K, Takiuchi H. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1063-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kinoshita T, Sasako M, Sano T, Katai H, Furukawa H, Tsuburaya A, Miyashiro I, Kaji M, Ninomiya M. Phase II trial of S-1 for neoadjuvant chemotherapy against scirrhous gastric cancer (JCOG 0002). Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tachimori Y, Hokamura N, Igaki H. [Salvage esophagectomy after definitive chemoradiotherapy]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;112:117-121. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yano M, Shiozaki H, Inoue M, Tamura S, Doki Y, Yasuda T, Fujiwara Y, Tsujinaka T, Monden M. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by salvage surgery: effect on survival of patients with primary noncurative gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:1155-1159. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bausewein C, Le Grice C, Simon S, Higginson I. The use of two common palliative outcome measures in clinical care and research: a systematic review of POS and STAS. Palliat Med. 2011;25:304-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miyashita M, Yasuda M, Baba R, Iwase S, Teramoto R, Nakagawa K, Kizawa Y, Shima Y. Inter-rater reliability of proxy simple symptom assessment scale between physician and nurse: a hospital-based palliative care team setting. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19:124-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miyashita M, Matoba K, Sasahara T, Kizawa Y, Maruguchi M, Abe M, Kawa M, Shima Y. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Support Team Assessment Schedule (STAS-J). Palliat Support Care. 2004;2:379-385. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, Miyashita K, Nishizaki T, Kobayashi O, Takiyama W. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1320] [Cited by in RCA: 1418] [Article Influence: 83.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mahar AL, Coburn NG, Karanicolas PJ, Viola R, Helyer LK. Effective palliation and quality of life outcomes in studies of surgery for advanced, non-curative gastric cancer: a systematic review. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S138-S145. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mahar AL, Coburn NG, Singh S, Law C, Helyer LK. A systematic review of surgery for non-curative gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S125-S137. [PubMed] |