Published online Dec 27, 2012. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i12.284

Revised: October 17, 2012

Accepted: December 20, 2012

Published online: December 27, 2012

AIM: To detect the effect of intraoperative prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) infusion on survival of esophagectomized patients due to cancer.

METHODS: In this preliminary study, a double blinded placebo based clinical trial was performed. Thirty patients with esophageal cancer scheduled for esophagectomy via the transthoracic approach were randomized by a block randomization method, in two equal groups: PGE1 group - infusion of PGE1 (20 ng/kg per minute) in the operating room and placebo group - saline 0.9% with the same volume and rate. The infusion began before induction of anesthesia and finished just before transfer to the intensive care unit. The patients, anesthetist, intensive care physicians, nurses and surgeons were blinded to both study groups. All the patients were anesthetized with the same method. For postoperative pain control, a thoracic epidural catheter was placed for all patients before induction of anesthesia. We followed up the patients until October 2010. Basic characteristics, duration of anesthesia, total surgery and thoracotomy time, preoperative hemoglobin, length of tumor, grade of histological differentiation, disease stage, number of lymph nodes in the resected mass, number of readmissions to hospital, total duration of readmission and survival rates were compared between the two groups. Some of the data originates from the historical data reported in our previous study. We report them for better realization of the follow up results.

RESULTS: The patients’ characteristics and perioperative variables were compared between the two groups. There were no significant differences in age (P = 0.48), gender (P = 0.27), body mass index (P = 0.77), American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status more than I (P = 0.71), and smoking (P = 0.65). The PGE1 and placebo group were comparable in the following variables: duration of anesthesia (277 ± 50 vs 270 ± 67, P = 0.86), duration of thoracotomy (89 ± 35 vs 96 ± 19, P = 0.46), duration of operation (234 ± 37 vs 240 ± 66, P = 0.75), volume of blood loss during operation (520 ± 130 vs 630 ± 330, P = 0.34), and preoperative hemoglobin (14.4 ± 2 vs 14.7 ± 1.9, P = 0.62), respectively. No hemodynamic complications requiring an infusion of dopamine or cessation of the PGE1 infusion were encountered. Cancer variables were compared between the PGE1 and placebo group. Length of tumor (11.9 ± 3 vs 12.3 ± 3, P = 0.83), poor/undifferentiated grade of histological differentiation [3 (20%) vs 3 (20%), P = 0.78], disease stage III [5 (33.3%), 4 (26.7%), P = 0.72] and more than 3 lymph nodes in the resected mass [3 (20%) vs 2 (13.3%), P = 0.79] were similar in both groups. All the patients were discharged from hospital except one patient in the control group who died because of a post operative myocardial infarction. No life threatening postoperative complication occurred in any patient. The results of outcome and survival were the same in PGE1 and placebo group: number of readmissions (2.1 ± 1 vs 1.9 ± 1, P = 0.61), total duration of readmission (27 ± 12 vs 29 ± 12, P = 0.67), survival rate (10.1 ± 3.8 vs 9.6 ± 3.4, P = 0.71), overall survival rate after one year [8 (53.3%) vs 7 (47%), P = 0.72], overall survival rate after two years [3 (20%) vs 3 (20%), P = 0.99], and overall survival rate after three years [0 vs 1 (6.7%), P = 0.99], respectively.

CONCLUSION: In conclusion, PGE1 did not shorten or lengthen the survival of patients with esophageal cancer. Larger studies are suggested.

- Citation: Farrokhnia F, Makarem J, Mahmoodzadeh H, Andalib N. Does perioperative prostaglandin E1 affect survival of patients with esophageal cancer? World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4(12): 284-288

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v4/i12/284.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v4.i12.284

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide. In spite of improvements in systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy, multimodality treatment and surgical processes, its mortality is considerable[1].

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) is derived enzymatically from fatty acids with effects on immunity and the vascular system[2-4]. In several previous reports, administration of a low dose of PGE1 has been shown to be advantageous in early postoperative periods, such as improved oxygenation[5,6].

Attenuation of systemic inflammatory response syndrome[7], prevention and treatment of postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome[8], prevention of ischemic injuries[2], shorter stays in the intensive care unit and hospital[9,10] and reduced mortality rate[10,11] have been reported.

PGE1 is administered in surgeries due to malignancies[5,10]. Its complex and comprehensive effects on the immune system have been shown previously but its long term effects on these patients have not been reported previously. We could not find any reports that directly assessed the effects of PGE1 on cancer cells in vitro or in vivo. There is no report about PGE1 effects on survival of cancer patients. Therefore, we decided to measure the survival of patients who were esophagectomized because of cancer and received PGE1 during the operation in a preliminary study. We followed up the patients who enrolled in our previous trial[10] and measured their survival and outcome.

We used the same patients and study from our previous publication[10] and the current manuscript is only the report of the follow up of the previous study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and written informed consent was obtained from each patient. This preliminary randomized placebo based trial was performed from October 2007 to October 2010 in a university referral cancer center. All patients scheduled for a transthoracic approach esophagectomy due to cancer were entered in the study. Exclusion criteria from the study were age older than 75 years, preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, steroid administration before operation, any antibiotic therapy (except preoperative prophylactic antibiotic administration), esophageal reconstruction using a segment of jejunum or colon, applying laparoscopy or thoracoscopy, trans-hiatal esophagectomy, any acute or chronic inflammatory or infectious disease and any acute or chronic lung disease.

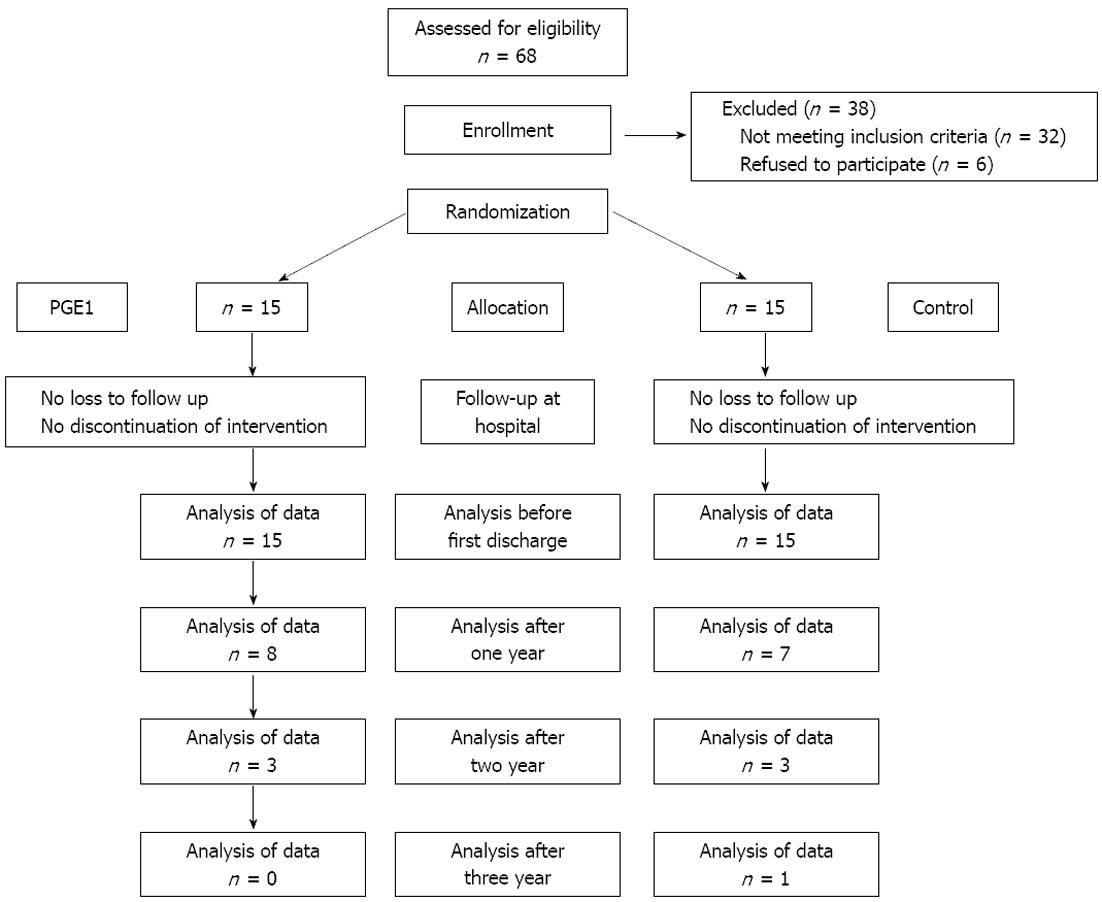

By application of a block randomization method, thirty patients were allocated to two equal groups: the PGE1 and placebo group. All the patients were followed after randomization and nobody was excluded from the study (Figure 1). In the PGE1 group, PGE1 (Prostin VR; Pharmacia and Upjohn, Puurs, Belgium) was infused with a dose of 20 ng/kg per minute in the operating room. The infusion began before induction of anesthesia and finished just before transfer to the intensive care unit. In the placebo group, saline 0.9% with the same volume and rate was infused. The patients, anesthetist, intensive care physicians, nurses and surgeons were blinded to the intervention group.

A thoracic epidural catheter was placed for all the patients before induction of anesthesia, with a midline approach through vertebral interspaces between T6-L1. Then, an epidural bolus dose of 3-4 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% was injected and the catheter was fixed to the skin.

Patients were premedicated with midazolam 0.05 mg/kg and sufentanil 0.2 μg/kg five minutes before induction of anesthesia. Anesthesia was induced by thiopental sodium 5 mg/kg. Cisatracurium 0.15 mg/kg was given to facilitate tracheal intubation. General anesthesia was maintained by 1.5%-2.0% (inspired concentration) isoflurane in oxygen. Additional cisatracurium and sufentanil were given when required.

In the postoperative period, patients were admitted to an intensive care unit and received similar care according to a specified protocol. After discharge from hospital, patients were followed up in a postoperative surgery clinic and by phone until October 2010.

Basic characteristics, duration of anesthesia, total surgery and thoracotomy time, preoperative hemoglobin, length of tumor, grade of histological differentiation, disease stage, number of lymph nodes in resected mass, number of readmissions to hospital, total duration of readmission and survival rates were compared between the two groups.

The main goal of this study was assessment of PGE1’s effects on survival of the patients. However, in this preliminary study we did not calculate the sample size.

The continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for goodness of fit to normal distribution was performed and normality was obtained for all measurements. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of the means of continuous variables. Categorical variables are given as counts and group comparisons were made with the χ2 test. All calculations were performed with SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A probability level P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Also, some of the data originates from the historical data reported in our previous study[10], such as Table 1, and we report them for better realization of the follow up results.

| PGE1 group (n = 15) | Control group (n = 15) | P value | |

| Age (yr)1 | 54 ± 9 | 57 ± 8 | 0.48 |

| Gender (male)2 | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 0.27 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)1 | 31 ± 4 | 32 ± 3 | 0.77 |

| ASA physical status (> I)2 | 9 (60) | 10 (66.7) | 0.71 |

| Smoking2 | 2 (13.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0.65 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (g/dL)1 | 14.4 ± 2 | 14.7 ± 1.9 | 0.62 |

| Duration of anesthesia (min)1 | 277 ± 50 | 270 ± 67 | 0.86 |

| Duration of operation (min)1 | 234 ± 37 | 240 ± 66 | 0.75 |

| Duration of thoracotomy (min)1 | 89 ± 35 | 96 ± 19 | 0.46 |

| Blood loss (mL)1 | 520 ± 130 | 630 ± 330 | 0.34 |

The patients’ characteristics and perioperative variables are depicted (Table 1). There were no significant differences in basic characteristics. Duration of anesthesia, thoracotomy and operation, volume of blood loss during operation and preoperative hemoglobin were comparable between the two groups. No hemodynamic complications requiring an infusion of dopamine or cessation of the PGE1 infusion were encountered.

Cancer variables are shown (Table 2). Length of tumor, grade of histological differentiation, disease stage and number of lymph nodes in the resected mass were similar in both groups.

| PGE1 group(n = 15) | Control group (n = 15) | P value | |

| Length of tumor (cm)1 | 11.9 ± 3 | 12.3 ± 3 | 0.83 |

| Grade of histological differentiation2 | |||

| Good | 3 (20) | 4 (26.7) | 0.78 |

| Intermediate | 9 (60) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Poor | 2 (13.3) | 3 (20) | |

| Undifferentiated | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Disease stage2 | |||

| IIA | 8 (53.3) | 10 (66.7) | 0.72 |

| IIB | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | |

| III | 5 (33.3 ) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Number of lymph nodes in resected mass2 | |||

| 0 | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0.79 |

| 1-3 | 7 (46.7) | 9 (60) | |

| ≥ 4 | 3 (20) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Pathological T12 | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0.75 |

| Pathological T2 | 1 (6.7) | 3 (20) | |

| Pathological T3 | 12 (80) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Pathological N12 | 5 (33.3) | 6 (40) | 0.99 |

All the patients were discharged from hospital except for one patient in the control group who died because of a post operative myocardial infarction. No life threatening postoperative complication occurred in any patient.

Patients were followed up for nearly 3 years and the results of outcome and survivals are presented (Table 3). PGE1 and placebo groups were comparable in the number of readmissions to hospital, total duration of readmission and different survival rates (P > 0.05).

| PGE1 group (n = 15) | Control group (n = 15) | P value | |

| Number of readmissions to hospital1 | 2.1 ± 1 | 1.9 ± 1 | 0.61 |

| Total duration of readmission (d)1 | 27 ± 12 | 29 ± 12 | 0.67 |

| The survival rate (mo)1 | 10.1 ± 3.8 | 9.6 ± 3.4 | 0.71 |

| The overall survival rate after 1 yr | 8 (53.3) | 7 (47) | 0.72 |

| The overall survival rate after 2 yr | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | 0.99 |

| The overall survival rate after 3 yr | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0.99 |

In this preliminary study, we did not find that an intraoperative infusion of PGE1 had any significant effects on outcomes or survival parameters of esophagectomized patients in comparison with a placebo.

Surgery related stress may cause a metabolic and systemic inflammatory response in major operations[12]. It is believed that prostaglandins, cytokines, chemokines, cyclooxygenase and other products of an uncontrolled inflammatory response could advance cancer progression via immunosuppression, resistance to apoptosis and promotion of angiogenesis[13]. However, the role of acute inflammation, especially due to the perioperative period and surgical stress, in recurrence or metastasis of cancer has not been fully studied.

In the perioperative period, an increase in the level of cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8, in combination with several other changes in the inflammatory system could account for profound suppression of natural killer cytotoxic activity[14]. PGE1 regulates the immune response to tissue trauma by various mechanisms. It modifies the release of inflammatory mediators[15], shortens the duration of systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and also attenuates the severity of systemic inflammatory response syndrome after esophagectomy[7]. It has been shown that infusion of PGE1 attenuates the increase in serum levels of IL-6[5,10] and IL-8[16]. Therefore, in a perioperative acute inflammatory condition, PGE1 may attenuate the effect of the inflammatory system on suppression of natural killer (NK) cytotoxic activity. So, it could be supposed that infusion of PGE1 indirectly could prevent the defects in NK cytotoxic activity and consequently improve defence against cancerous cells.

The results of this preliminary study should be interpreted cautiously because of several limitations in the study. This study was based on a small sample size. We did not calculate the proper sample size, with considering survival parameters and outcome as the main goal. We have not considered other important factors, such as the disease state, as well as postoperative treatment and care.

In conclusion, PGE1 did not shorten or lengthen the survival of patients with esophageal cancer. The study of the effects of PGE1 on the promotion of cancer is recommended.

We warmly thanks Dr. Farinaz Safavi for text editing.

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide. In spite of improvements in systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy, multimodality treatment and surgical processes, its mortality is considerable. Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) is derived enzymatically from fatty acids with effects on immunity and the vascular system. PGE1 is administered in surgeries due to malignancies. Its complex and comprehensive effects on the immune system have been shown previously but its long term effect on these patients has not been reported previously.

In a perioperative acute inflammatory condition, PGE1 may attenuate the effect of the inflammatory system on suppression of natural killer (NK) cytotoxic activity. So, it could be supposed that an infusion of PGE1 indirectly could prevent the defects in NK cytotoxic activity and consequently improve defence against cancerous cells.

PGE1 did not shorten or lengthen the survival of patients with esophageal cancer. The study of the effects of PGE1 on the promotion of cancer is recommended.

The aim of this study was to assess the effects of PGE1 on survival of esophageal cancer patients who underwent surgery. It was previously reported that perioperative administration of PGE1 reduced the risk of postoperative complications, yet the long term effect of PGE1 on patient survival has not been studied.

Peer reviewer: Lizi Wu, Assistant Professor, Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, University of Florida, Cancer and Genetics Research Complex, Rm 362, Gainesville, FL 32610, United States

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2591] [Cited by in RCA: 2645] [Article Influence: 139.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hanazaki K, Kuroda T, Kajikawa S, Shiohara E, Haba Y, Iida F. Prostaglandin E1 protects liver from ischemic damage. J Surg Res. 1994;57:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Beck PL, McKnight GW, Kelly JK, Wallace JL, Lee SS. Hepatic and gastric cytoprotective effects of long-term prostaglandin E1 administration in cirrhotic rats. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1483-1489. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Haynes DR, Whitehouse MW, Vernon-Roberts B. The prostaglandin E1 analogue, misoprostol, regulates inflammatory cytokines and immune functions in vitro like the natural prostaglandins E1, E2 and E3. Immunology. 1992;76:251-257. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Nakazawa K, Narumi Y, Ishikawa S, Yokoyama K, Nishikage T, Nagai K, Kawano T, Makita K. Effect of prostaglandin E1 on inflammatory responses and gas exchange in patients undergoing surgery for oesophageal cancer. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:199-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gee MH, Tahamont MV, Flynn JT, Cox JW, Pullen RH, Andreadis NA. Prostaglandin E1 prevents increased lung microvascular permeability during intravascular complement activation in sheep. Circ Res. 1987;61:420-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oda K, Akiyama S, Ito K, Kasai Y, Fujiwara M, Sekiguchi H, Nakao A, Sakamoto J. Perioperative prostaglandin E1 treatment for the prevention of postoperative complications after esophagectomy: a randomized clinical trial. Surg Today. 2004;34:662-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Leithner C, Frass M, Traindl O. PGE1 for prevention and treatment of ARDS after surgery. Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin: Springer Company 1989; 80-85. |

| 9. | Klein AS, Cofer JB, Pruett TL, Thuluvath PJ, McGory R, Uber L, Stevenson WC, Baliga P, Burdick JF. Prostaglandin E1 administration following orthotopic liver transplantation: a randomized prospective multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:710-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Farrokhnia E, Makarem J, Khan ZH, Mohagheghi M, Maghsoudlou M, Abdollahi A. The effects of prostaglandin E1 on interleukin-6, pulmonary function and postoperative recovery in oesophagectomised patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37:937-943. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Henley KS, Lucey MR, Normolle DP, Merion RM, McLaren ID, Crider BA, Mackie DS, Shieck VL, Nostrant TT, Brown KA. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of prostaglandin E1 in liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1995;21:366-372. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Gupta S. Immune response following surgical trauma. Crit Care Clin. 1987;3:405-415. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kundu JK, Surh YJ. Inflammation: gearing the journey to cancer. Mutat Res. 2008;659:15-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goldfarb Y, Ben-Eliyahu S. Surgery as a risk factor for breast cancer recurrence and metastasis: mediating mechanisms and clinical prophylactic approaches. Breast Dis. 2006;26:99-114. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sullivan TJ, Parker KL, Stenson W, Parker CW. Modulation of cyclic AMP in purified rat mast cells. I. Responses to pharmacologic, metabolic, and physical stimuli. J Immunol. 1975;114:1473-1479. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kawamura T, Nara N, Kadosaki M, Inada K, Endo S. Prostaglandin E1 reduces myocardial reperfusion injury by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines production during cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2201-2208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |