CASE REPORT

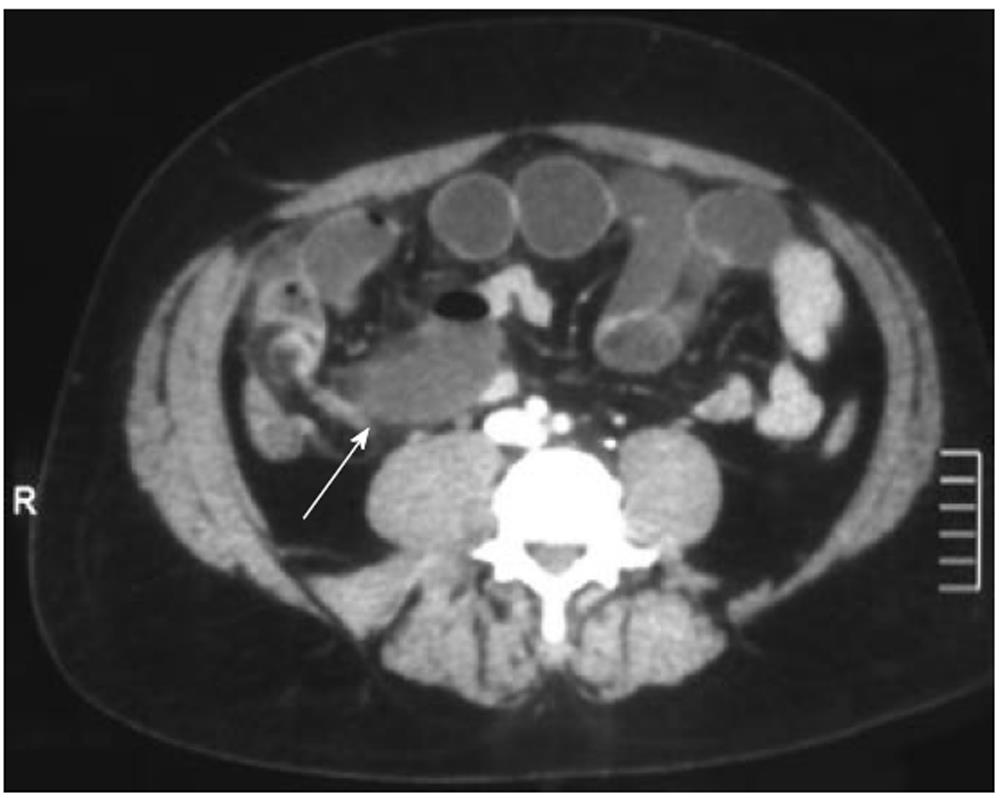

A 42-year-old man was referred to our department with a 24-h history of lower quadrant and suprapubic pain and several episodes of vomiting without flatus. The abdominal pain initially started as colicky in nature. He denied fever. The medical history was notable for one prior discrete episode, 1 mo previously, with similar clinical features, resolving over 1 d with observation. On initial examination, his vital signs were: blood pressure 120/80 mmHg, pulse rate 110 beats/min, respiration rate 16 breaths/min, and temperature 37.5°C. Laboratory examination demonstrated leukocytosis at 19 100/MCL, 90% neutrophils, and normal haemoglobin, electrolytes, creatinine, AST, and amylase. On physical examination, the abdomen was distended and tender with guarding and rebound on the lower abdomen, mainly on the right. Bowel sounds were present but of diminished intensity. No abdominal scars or hernias were present. Rectal examination was negative. The abdominal plain radiograph showed multiple air-fluid levels. Due to atypical presentation (suspected appendicitis, bowel obstruction of uncertain origin with intestinal ischemia) a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan was performed. A transition point between dilated and collapsed small bowel in the right lower quadrant consistent with a high grade small bowel obstruction was found. A blind-ending fluid-filled structure of unclear origin, in continuity with the small bowel was noted (Figure 1). There was no evidence of appendicitis. In the absence of any evident cause of obstruction and for signs of ischemia, urgent exploratory laparotomy was planned. At exploration, a moderate amount of intraperitoneal serohemorrhagic fluid was found; the cecum and appendix appeared to be normal. A part of the small intestine was entrapped and strangulated between a giant axial torsed gangrenous MD and a fibrous band connecting the tip of the diverticulum to the mesentery. The giant gangrenous MD, measuring 11 cm in length and with 1.5 cm base, was found 50 cm proximal to the ileoceacal valve, in the right iliac fossa (Figure 2). The band was lysed, unfolding the bowel and MD. The diverticulum was resected using a GIA stapler, without small bowel resection. The patient was discharged without any problems after a 7-d hospital stay.

Figure 1 Contrast-enhanced computed tomography images show blind-ending fluid-filled structure (arrow) resulting in small-bowel obstruction.

Operative findings confirmed Meckel’s diverticulum.

Figure 2 Segment of ileum with a giant gangrenous Meckel’s diverticulum after derotation.

DISCUSSION

MD is the most common congenital gastrointestinal abnormality. It was first described by Fabricius Hildanus in 1598 and later named after Johann Friedrich Meckel, a German comparative anatomist who first recognized its developmental origin in 1809[7]. MD results from the persistence of a portion of the omphalomesenteric duct, which connects the primitive gut to the yolk sac in early fetal life. Lack of elimination results in either an MD with or without a fibrous connection to the umbilicus or a fistula from the small bowel to the umbilicus[8]. These are true diverticula containing all the layers of the small bowel wall, which are located on the antimesenteric border, and are found typically within 1 meter of the ileocecal valve. Gastric heterotopias can be found in roughly 50% of cases, and pancreatic, duodenal, colonic, or biliary mucosa have rarely been reported[9]. The lifetime risk of complications in patients with an MD is only 4%. The three most common complications of MD are bleeding, obstruction, and inflammation. It has been reported that symptomatic MD is more common in men, with a male/female ratio of 2:1 to 5:1[10]. Forty percent of these complications occur in children younger than 10 years, who usually present with GI bleeding. A risk of 3.7% at age 16 years, decreasing to zero by 76 years of age, has been reported[11]. Adults develop obstructions or, less frequently, symptoms of inflammation. Hemorrhage is much less common in adults and is usually the result of heterotopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa causing ulceration[12]. Obstruction of various types is the most common presenting symptom in the adult population, occurring in almost 40% of patients[13].

The most common obstruction was intussusception or invagination, with the MD being the lead point. Other obstructions include volvulus around fibrous bands adherent to the umbilicus, and inflammatory adhesions, Littre’s hernias and diverticular strictures. Uncommon causes of obstruction include enteroliths being expulsed from the diverticulum forming a distal obstruction, and loop formations with the end of an MD and adjacent mesentery constricting the distal ileum[4]. Axial torsion of an MD is a rare complication[5,12,13] that results from axial twisting of an MD around its narrow base. In addition to this, gangrene of MD, secondary to axial torsion, as in our patient, is an extremely rare phenomenon. It has been reported only seven times in adults[5,13,14,15]. Axial torsion of the diverticulum around its base, and consequent gangrene, has been related to the attachment of the diverticulum to the umbilicus or to the ileal mesentery. Axial torsion of the diverticulum, around a narrow base can also occur[5,15]. The anatomical configuration, especially the diverticular length and base diameter is an important predisposing factor[3,15,16]. The size is variable, but diverticulum typically presents as short and wide- mouthed (on average it is 2.9 cm long and 1.9 cm wide)[13]. In our case, a diverticulum with such dimensions (11 cm in length with a 1.5 cm base), represents a rare case in itself. An elongated variant with a narrowed neck is far more likely to result in torsion[3], whereas short, large-base diverticula are subject to foreign body entrapment[10]. Obstruction has been found to occur more frequently with a giant MD[3,17]. An axial torsion of a giant MD can also be incomplete and recurrent, resulting in repeated episodes of intestinal subocclusion[3]. In our case there was the coexistence of gangrenous MD and its loop-forming mechanism of obstruction; this is a very rare co-occurrence and to the best of our knowledge only one case has been reported in the English-speaking literature[6]. Sharma et al[6] reported mechanical reasons to explain this coexistence: the process of herniation of the portion of terminal ileum in the loop of MD, might have caused an axial rotation of the MD resulting in compromised blood supply and gangrene. The second most common complication in adults appears to be related to an inflammatory process. Diverticulitis and perforation occur at a combined rate of almost 20% and are often indistinguishable from acute appendicitis until visualization in the operating room[4]. Post-inflammatory gangrene is infrequent, occurring only in the case of late diagnosis, as the symptoms of diverticulitis are intense, leading to diagnosis and therefore to surgical treatment[13]. The correct diagnosis of MD before surgery is often difficult because a complicated form of this condition may be clinically indistinguishable from a variety of other intra-abdominal diseases such as acute appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or other causes of small bowel obstruction[18]. Bani-Hani et al[19] reported a preoperative diagnosis in only four patients (5.9%) in a symptomatic group of 28 patients. Similarly, Lüdtke et al[20] reported preoperative diagnoses in only 4% of their cases. Small bowel obstruction is usually visible on plain films of the abdomen. On CT, MD is difficult to distinguish from the normal small bowel in uncomplicated cases. However, a blind-ending fluid or gas-filled structure in continuity with the small bowel may be seen[17]. CT enteroclysis is an alternative to conventional CT if a small bowel lesion is suspected[21]. MD can be diagnosed by ultrasound in cases of complications[22]. Ultrasonography, which may reveal pelvic abscess, a tubular fluid-distended diverticulum at a site far from the cecum, diverticular wall swelling, segmental thickening of the intestinal walls, and invagination, is not sufficiently specific[23]. Arteriography and technetium pertechnetate scanning are useful only if there is significant bleeding or ectopic gastric mucosa[2]. Finally, laparoscopy, as a diagnostic tool in cases of symptomatic MD, has also been reported[7]. Delay in the diagnosis of a complicated MD can lead to significant morbidity and mortality[13,24]. Some authors have reported the high mortality rate of a MD with a mesodiverticular band and intestinal obstruction[24].

Surgical treatment of MD may be by open or laparoscopic procedures. Surgical treatment options include simple diverticulectomy or ileal resection. Associated bands should be removed. Laparoscopic resection of MD is feasible and ideal, especially when performed in specialized centers; techniques including intra-abdominal wedge resection or extracorporeal or intracorporeal bowel segment resection have been reported[1]. Results of surgical excision are generally excellent. Of the patients operated on for complications of MD, the cumulative incidence of early postoperative complications was 12%, including mainly wound infection (3%), prolonged ileus (3%), and anastomotic leak (2%). The mortality rate was 1.5%. The cumulative incidence of late postoperative complications during a 20-year followup was 7%. Incidental diverticulectomies are safer, with an overall rate of morbidity and mortality of 2% and 1% respectively[25]. Our patient underwent a diverticulectomy without small bowel resection only due to a laparotomy after an earlier CT scan and there were no early postoperative complications.

In conclusion, we report a very rare form of acute small bowel obstruction secondary to giant torsed gangrenous MD encircling the terminal ileum. The herniation of the portion of terminal ileum in the loop of MD might have caused axial rotation of MD resulting in compromised blood supply and gangrene. The preoperative diagnosis is often difficult and presumed to be appendicitis or small bowel obstruction of unclear etiology. The correct diagnosis of MD could only be made during surgery. Early surgery is important to prevent strangulation and gangrene of the bowel. MD should be kept in mind in patients with atypical presentations.