Published online Apr 27, 2011. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v3.i4.43

Revised: March 25, 2011

Accepted: April 1, 2011

Published online: April 27, 2011

To review the classification and general guidelines for treatment of bile duct injury patients and their long term results. In a 20-year period, 510 complex circumferential injuries have been referred to our team for repair at the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” hospital in Mexico City and 198 elsewhere (private practice). The records at the third level Academic University Hospital were analyzed and divided into three periods of time: GI-1990-99 (33 cases), GII- 2000-2004 (139 cases) and GIII- 2004-2008 (140 cases). All patients were treated with a Roux en Y hepatojejunostomy. A decrease in using transanastomotic stents was observed (78% vs 2%, P = 0.0001). Partial segment IV and V resection was more frequently carried out (45% vs 75%, P = 0.2) (to obtain a high bilioenteric anastomosis). Operative mortality (3% vs 0.7%, P = 0.09), postoperative cholangitis (54% vs 13%, P = 0.0001), anastomosis strictures (30% vs 5%, P = 0.0001), short and long term complications and need for reoperation (surgical or radiological) (45% vs 11%, P = 0.0001) were significantly less in the last period. The authors concluded that transition to a high volume center has improved long term results for bile duct injury repair. Even interested and tertiary care centers have a learning curve.

- Citation: Mercado MA, Domínguez I. Classification and management of bile duct injuries. World J Gastrointest Surg 2011; 3(4): 43-48

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v3/i4/43.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v3.i4.43

Bile duct injuries (BDI) take place in a wide spectrum of clinical settings. The mechanisms of injury, previous attempts of repair, surgical risk and general health status importantly influence the diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making pathway of every single case. A multidisciplinary approach including internal medicine, surgery, endoscopy and interventional radiology specialists is required to properly manage this complex disease. BDI may occur after gallbladder, pancreas and gastric surgery, with laparoscopic cholecystectomy responsible for 80%-85% of them[1-3]. Although not statistically significant, BDI during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is twice as frequent compared to injuries during an open procedure (0.3% open vs 0.6% laparoscopic)[4]. BDIs are a complex health problem and, although they usually occur in healthy young people, the effect on the patient’s quality of life and overall survival is substantial[5]. The two most frequent scenarios are bile leak and bile duct obstruction. Most of BDIs after laparoscopic cholecystectomy are recognized transoperatively or in the immediate postoperative period[6,7]. Bile leak scenario is easily recognized during the first postoperative week. Constant bile effusion is documented through surgical drains, surgical wounds or laparoscopic ports. Patients usually complain of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, fever and impaired intestinal motility. In addition, bile collections, peritonitis, leukocytosis and mixed hyperbilirubinemia may be part of the clinical setting[8,9]. An obstructive pattern in liver function tests accompanied by jaundice is frequent in the biliary obstruction scenario. Most of these patients have a complex Strasberg E injury recognized in the transoperative period. However, if not identified during the first postoperative week, patients have an insidious evolution with relapsing abdominal pain and cholangitis as well as bile collections. Jaundice is not always present immediately after bile duct injury. Some partial stenosis and isolated sectorial right duct lesions (Strasberg B and C) present with abdominal pain, pruritus, general weakness, fever and intermittent alteration of liver function tests.

Unfortunately, late diagnosis, multiple repair attempts and neglected medical care in order to avoid legal entanglements result in extension and increased complexity of bile duct repair. The late clinical course of bile duct injury leads to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and portal hypertension, with liver transplantation the last hope of cure.

Multiple classifications have been developed before and after the laparoscopic era. The Bismuth-Corlette classification was introduced before laparoscopy. It is difficult to apply in laparoscopic cholecystectomy as most of the technical factors and lesion mechanisms are completely different to open surgery. It considers the complete section of the common bile duct and the length of the proximal bile duct stump[10]. Nevertheless, most cases have late stenosis or bile duct obstruction which may be included in this classification, representing a subtype Strasberg E and Stewart-Way III-IV lesions.

Type I is a low injury with a stump length more than 2 cm. Type II is a middle level injury with a stump length less than 2 cm. Type III is a high level injury without common hepatic duct available but preserved confluence. Type IV involves loss of hepatic confluence with no communication between right and left ducts.

This classification involves four strata based on the mechanism and anatomy of injury.

Class I refers to the incomplete section of bile duct with no loss of tissue. It has a prevalence rate of 7%. The first mechanism of injury is a misleading recognition of the common hepatic duct with the cystic duct but is rectified and results in only a small loss of tissue with no complete section of the bile duct. The second mechanism refers to the lateral injury of the common hepatic duct which results from the cystic duct opening extension during cholangiography. The former represents 72% and the latter 28% of class I cases.

Class II is a lateral injury of the common hepatic duct that leads to stenosis or bile leak. It is the consequence of thermal damage and clamping the duct with surgical staples. It has a prevalence of 2% with a concomitant hepatic artery injury in 18% of cases. T-tube related injuries are included within this class.

Class III is the most common (61% of cases) and represents the complete section of the common hepatic duct. It is subdivided in to type IIIa, remnant common hepatic duct; type IIIb, section at the confluence; type IIIc, loss of confluence; and type IIId, injuries higher than confluence with section of secondary bile ducts. It occurs when the common hepatic duct is confounded with the cystic duct, leading to a complete section of the common hepatic duct when resecting the gallbladder. A concomitant injury of right hepatic artery occurs in 27% of cases.

Class IV describes the right (68%) and accessory right (28%) hepatic duct injuries with concomitant injury of the right hepatic artery (60%). Occasionally it includes the common hepatic duct injury at the confluence (4%) besides the accessory right hepatic duct lesion. Class IV has a prevalence of 10%[11,12].

To our knowledge, the Strasberg classification of BDI is the most complete and easy to understand. It divides in to five groups (A to E) where the E class is analog to the Bismuth classification, a complex bile duct injury with a complete section of the duct.

Only right and left partial injuries are not included in this classification. Despite the fact that the latter are infrequent injuries (8% and 4% respectively in our series), it is important for the surgeon to be aware of them in order to make a proper diagnosis and timely referral.

Class A represents a bile leak from the cystic duct or an accessory duct. In both conditions there is continuity with the common bile duct. Class B is the section of an accessory duct with no continuity with the common bile duct. Class C represents a leak from a bile duct with no continuity with the common bile duct. Class D is a partial section of a bile duct with no complete loss of continuity with the rest of the bile duct system. Class E is a complete section of the bile duct with subtypes according to the length of the stump (E1-E5). It also includes the loss of confluence and injury to accessory ducts[13].

This was published in 2007 but is poorly known in the world literature. It classifies injuries in relationship to the confluence and also includes vascular injuries. It has five subtypes. Type A refers to cystic and/or gallbladder bed leaks. Type B is a complete or incomplete stenosis caused by a surgical staple. Type C represents lateral tangential injuries. Type D refers to complete section of the common bile duct emphasizing their distance to the confluence as well as the hepatic artery and portal vein concomitant injuries. Type E is late bile duct stenosis at different lengths to the confluence[12].

BDI must be treated according to the type of injury. The Strasberg classification is a helpful tool to decide the best intervention for each case according to etiological mechanism of injury.

As Strasberg A injuries maintain continuity with the rest of the bile ducts, they are easily treated through endoscopic intervention. The objective is to decrease intraductal pressure distal to the bile duct leak. If endoscopy is not available, a T tube could be useful.

The last resource is to control the bile leak through subhepatic drains and refer to a specialized center with enough experience to treat BDI[14].

It is difficult to prevent Strasberg A injury, except when the common bile duct obstruction is documented and properly treated before surgery.

Segmentary bile duct occlusion is the etiological factor in this type of injury. If mild pain and elevation of liver function tests are present with no clinical impairment, conservative management is followed. The presence of moderate and severe cholangitis makes the drainage of the occluded liver segment necessary. Percutaneous drainage or surgical resections can be performed when cholangitis is not controlled with medical treatment.

Biliodigestive derivation of segmentary bile ducts is technically hard to perform with only anecdotal cases being reported[15]. Long term prognosis is poor and there is a higher probability of bile colonization and cholangitis[16].

As in Strasberg B injury, an accessory right duct is sectioned but the proximal stump is not detected and occluded, with an unnoticed bile leak as a consequence. No continuity exists with the rest of the bile duct system, leaving endoscopy out of the therapeutic options.

Subhepatic collections are frequent in the postoperative setting. These must be drained in order to avoid biliary peritonitis and septic shock.

It is common that the bile leak is occluded spontaneously with no other intervention maintaining a controlled bile leak through external drains. If this does not happen, therapeutic options are the same that Strasberg B injury, biliodigestive derivation to segmentary ducts (also with poor long term prognosis), percutaneous drainage and hepatectomy.

A partial injury of the common bile duct in its medial side characterizes this type. No complete loss of bile duct continuity is present. If a small injury with no devascularization is present, a 5-0 absorbable monofilament suture to close the defect is adequate. In these rare cases, external drainage must be left in place and mandatory endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoprothesis should be performed.

In the setting of a devascularized duct, even if small 5-0 absorbable stitches are used, a bile leak will develop during the first postoperative week with concomitant bile collections. Management of these cases requires a multidisciplinary approach with endoscopy and radiological-guided drainage as the first therapeutic options. Surgery is the last resource of treatment when a loss of bile duct tissue is present and migration of a Strasberg D to E injury has taken place.

This injury is defined by a complete loss of common and/or hepatic bile duct continuity. Devascularization and loss of bile duct tissue obliges the surgeon to perform a high-quality hepatojejunal anastomosis. The latter procedure guarantees well-perfused bile ducts and a low tension anastomosis. The opposite is obtained when choledoco-choledoco or hepato-duodenum anastomosis are performed as devascularized ducts are used for the reconstruction and the duodenum tends to move downwards, increasing anastomotic tension, even if a Kocher maneuver is performed well in advance[17].

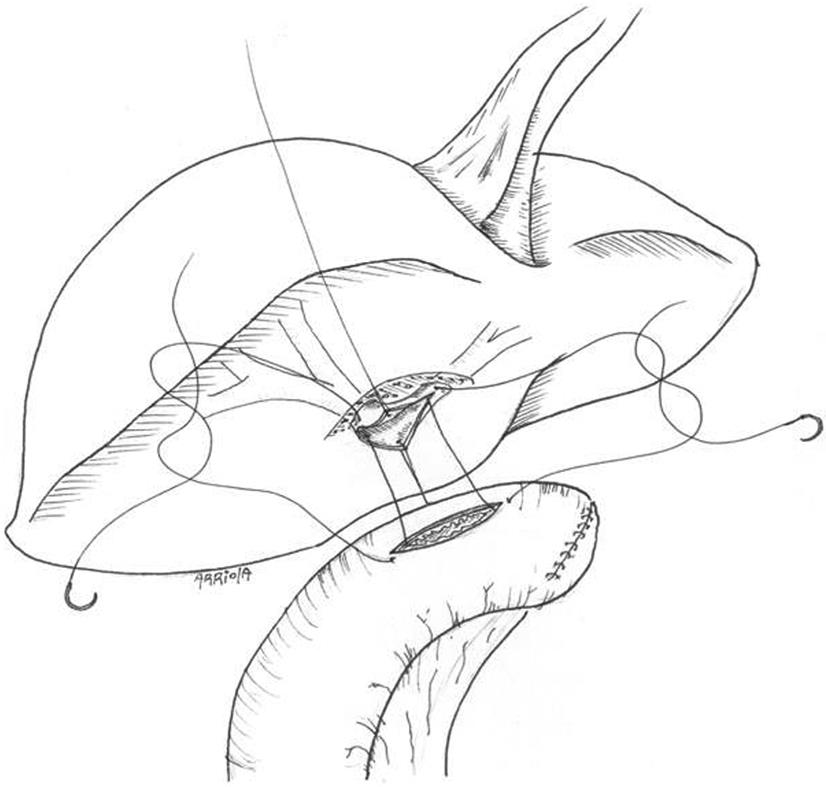

The best postoperative outcomes are obtained when the hepatic confluence is preserved, allowing a high-quality, wide, well vascularized hepatojejunal anastomosis. Partial resection of IV and V segments facilitates identification of bile ducts and proper settling of the jejunal loop[17,18].

In the unfortunate situation of inadequate ducts to perform a hepatojejunoanastomosis, the jejunal loop must be sutured to the liver parenchyma including ferulized bile ducts within the anastomosis similarly to a Kazai portoenterostomy[19]. Most of these cases are considered for liver transplant as postoperative outcomes after portoenterostomy are disappointing[20].

A retrospective review of the database of patients who have had bile duct reconstruction at our hospital from 1991 to 2008 was conducted. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Committee for Human Investigation at our hospital. All patients referred to our hospital are evaluated by a multidisciplinary team and the best option available is chosen for each individual patient. In this report only cases that were treated by means of surgery are included. All cases were treated by means of Roux en Y hepatojejunostomy, whose technical aspect has evolved in the last years[17,21]. Almost all the cases were performed by one surgeon (MAM).

Based on Strasberg’s definition, some cases were repaired at the index operation (when the injury occurred, early primary repair), other cases with delayed primary repair (6 wk or more after the injury) and, in the great majority of cases (more than 90%), secondary repairs (patients who had a prior attempt of reconstruction)[22].

At the beginning of our experience, the Bismuth classification was used[10]. From 1997 until now, the Strasberg classification has been used more frequently[13]. In the 1990s, ultrasound was used as the main imaging method with all the inherent limitations. Percutaneous cholangiography was used selectively and MR cholangiography has been used in the last decade as the most effective tool of visualizing the biliary tree.

Although a Roux en Y hepatojejunostomy has been used in every single case, the operative technique has evolved greatly. At the beginning of our experience, an end to side anastomosis with a transanastomotic stent was used for E1-E3 injuries[16]. In cases with E-4 or E-5 injuries, a porto enterostomy was done with transhepatic stents placed through the intestinal lumen. As we realized that the end to side anastomosis was sometimes jeopardized because of devascularization[4], we started to perform the anastomosis at the confluence level where well vascularized ducts were usually found. In order to reach the confluence, the anastomosis was always done in the anterior aspect of the ducts on order to preserve the circulation. In some cases lowering the hilar plate provided adequate ducts exposition for the anastomosis. In order to obtain a tension free, wide anastomosis (and as a result having more room for the intestinal loop) partial resection of segments IV and V was done[23]. Routine extension of the anterior opening of the common bile duct with direction to the left duct was done, particularly for thin ducts[24].

The utilization of transhepatic and transanastomotic stent decreased progressively so that they are placed only for cases in which a porto enterostomy has to be done. Major hepatectomy was done in some cases in which a duct was found with irreversible damage and/or the intrahepatic biliary tree was affected because of major arterial injury (right hepatic artery)[25].

In the last years, patients are scheduled for endoscopical or radiological treatment, mainly done when continuity of the bile ducts is shown and in some cases with stenosed bilio enteric anastomosis that can be dilated by percutaneous intervention. We use MRI routinely to evaluate the biliary tree and, seldom, we use percutaneous cholangiography, mainly indicated in patients with cholangitis, providing drainage and anatomical information.

Through a subcostal incision the porta hepatis is selectively dissected, preserving all the arterial branches found and the anterior aspect of the ducts is dissected free. This is enhanced with partial resection of segment IV and V parenchyma. The jejunal limb is anastomosed side to side with interrupted everted sutures of 5-0 hydrolysable monofilament suture (Figure 1).

Table 1 summarizes the results of the cohort divided in three periods. No differences were found in gender, age and type of operation (open or laparoscopic) in which the injury occurred. Most of the cases were secondary repairs and no differences were found for a given period of time. Partial segment IV and V resection had a significant increase. Usage of biliary transanastomotic stents decreased significantly. In the last period of time, only 2% of the cases had a stent placed at the time of repair. The rate of major hepatectomy remained without significant change.

| 1990-1999 | 2000-2004 | 2004-2008 | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 33 | 100 | 139 | 100 | 140 | 100 |

| Male | 6 | 18 | 39 | 28 | 31 | 22 |

| Female | 27 | 82 | 100 | 72 | 109 | 78 |

| Age (yr) | 38 ± 11 | 43 ± 15 | 40 ± 13 | |||

| Type of cholecystectomy | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Open | 27 | 82 | 104 | 75 | 89 | 63 |

| Lap | 6 | 18 | 35 | 25 | 51 | 36 |

| Previous repair | ||||||

| 0 | 17 | 51 | 72 | 52 | 71 | 51 |

| 1 | 13 | 39 | 58 | 41 | 60 | 42 |

| 2 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 7 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.7 |

| > 6 | 1 | 3 | . | . | 1 | 0.7 |

| SEG IV-V resection | 15 | 45 | 57 | 41 | 99 | 71 |

| Transanastomotic stent | 26 | 78 | 46 | 33 | 3 | 2 |

| Hepatectomy at repair | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Post op complications | ||||||

| Cholangitis | 18 | 54 | 35 | 25 | 19 | 13 |

| Stenosis | 10 | 30 | 13 | 9 | 7 | 5 |

| Abscesses | 5 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 6 |

| Fístula | 3 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Biloma | 4 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 18 | 13 |

| Reoperation | 15 | 45 | 25 | 18 | 16 | 11 |

| Hepatectomy post repair | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 | ||

| Operative mortality | 3 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0.7 |

Post operative complications also had significant changes. The rate of post operative long term cholangitis dropped to 13% and the rate of stenosis of the anastomosis to 5%. Although less frequent, no significant differences were found in the rate of postoperative abscesses, fistula or biloma. Need for reoperation (surgical or radiological) also dropped to 11%. Operation-related mortality decreased to less than 1% in the last period of time.

This study demonstrates that referral centers for bile duct injury repair, transitioning from low to high volume of cases, have a learning curve. Combining a high volume of cases with team experience, low mortality, acceptable peri and post operative morbidity and good long term results can be achieved.

Winslow and Strasberg have recently stated that technical aspects of repair are essential for early and long term success[22]. If the repair is done in well vascularized ducts, is done without tension and with the largest diameter possible (achieved with the anterior opening of the duct), with epithelium to mucosa apposition using sutures that produce minimum reaction and complete biliary tree drainage, good long term results can be achieved.

In the three periods analyzed, no differences were found in the general characteristics of the patients. In our center, secondary repair is the most frequent scenario that we face. In many centers, patients with history of bilioenteric anastomosis are treated radiologically with percutaneous dilation and/or transhepatic transanastomotic stent placement for subsequent dilation. Most of the cases with a stenosed bilioenteric anastomosis are surgically treated.

Indeed, the repair at the time of injury has not increased since our report about the repair in the acute setting. Only 1-2 cases per year are repaired by our team at the index operation. Some cases are referred after conversion, drainage and attempt of repair. These numbers certainly have a high variation according to the center, city and country analyzed. The best advice given to a surgeon for a laparoscopic injury is that if he/she is not able to do the repair and/or no interested experienced surgeon is available, it is better not to convert and only place several silastic drains though the laparoscopic ports before referring the patient to an interested center. Nevertheless, conversion is necessary in some cases in which bleeding control is mandatory and cannot be achieved though the laparoscope. In some instances, after conversion, the injury is produced with the maneuvers related to achieve hemostasis unfortunately.

The technical evolution of the repair has had a substantial variation through time. Nevertheless, in all our experience, we have always done Roux en Y hepatojejunostomy. No end to end anastomosis of the transected duct or hepatoduodenostomy has been done. Although several reports have good outcomes with this type of procedures, we do not favor them. Most of the injuries (result of the combination of ischemic injury and/or loss of substance) do not allow a tension free, well vascularized anastomosis (as is the case of liver transplantation). The result is early dehiscence and/or fistulization with late stenosis that in some cases in experienced groups has a good long term outcome[26]. Hepatoduodenostomy also has the same disadvantages. Although a wide Kocher maneuver, the anastomosis is not tension free. In these cases, when dehiscence or fistulization occurs, it results in a catastrophic outcome (biliary + duodenal fistula). In addition, direct contact with gastric contents and food (vegetables and other fibers) can result in anastomotic dysfunction.

At the beginning of our experience, we used to place transhepatic transanastomotic stents[16]. We agreed that leaks of a small bilioenteric anastomosis promote stenosis and that low pressure of the bile ducts were desirable and a flow through the anastomosis was warranted by the stents.

The opportunity to obtain a wide, non ischemic anastomosis at the hilar level began to restrict the usage of stents. A wide anastomosis allows free flow of the producing low duct pressure and less opportunity of leak. It also minimizes the risk of stricture and the need of subsequent instrumentation. Nevertheless, some cases with loss of confluence and complete destruction of the isolated right and left hepatic duct need a portoenterostomy, with no probability of obtaining a wide, tension free non ischemic anastomosis that need ferulization of the ducts, they obtain long term patency.

These types of anastomosis have the worst long term prognosis in our experience.

In the last period, the anastomosis was routinely done high in the hilum with the final goal of obtaining a high quality bilioenteric anastomosis with all the above explained requirements, particularly the circulatory status of the ducts.

This goal is obtained by removing the segments IV and V (a small wedge at its base) that also allow the lowering of the hilar plate when the parenchyma is retracted cephalically. Tissue resection is individually shaped according to the anatomical condition of the liver. Some cases have a well developed segment IV that not only obstructs the dissection of the left duct but also does not allow the placement of the jejunal limb. The resection is easy to achieve, allowing an anteroposterior view of the confluence (instead of a caudocephalic view) that permit a wide opening of a healthy left hepatic duct with well circulatory status suitable for a high quality anastomosis.

In cases with isolated right and left hepatic ducts, neoconfluence is built and the hepatojejunoanastomosis is done.

The better results obtained in the last period of time are related to refinement in the technical aspects of reconstruction but other issues have also been improved.

Classification of the injury nowadays is done initially with MRI cholangiography and in selected cases with ERCP and/or percutaneous radiology. These two options are used when continuity of the ducts (lateral injury) is suspected. Cases resolved by means of endoscopy and/or radiology are not included in this analysis. The failure of these methods, including the development of late stenosis of the duct (although patent), also indicated the need of reconstruction. Selection and timing of the operation has also been improved. Patients with active sepsis and multiple organ failure are not included for surgical repair until these issues are resolved. Some patients with these negative conditions were operated on early in our experience, explaining the higher mortality rate of the initial period.

The number of cases referred to our unit has been growing in the last years. There were 33 cases repaired in the first period of 10 years (all the cases done at other hospitals were excluded) and they have grown to 140 cases in the last 4 years. The total of repairs done by our team in the 19-year period is 510. The transition to a high volume center with the refinement in technical aspects allows better long and short term results.

In conclusion, this study shows that referral centers also have a learning curve and that a high volume of cases has repercussions in long term results due to refinement in technical aspects and selection of patients. It can also be advised that not only surgeons with low volume of repair but also centers with a low volume of repair should redirect these cases to interested facilities.

Peer reviewers: Grigory G Karmazanovsky, Professor, Department of Radiology, Vishnevsky Istitute of Surgery, B Serpukhovskaya street 27, Moscow 117997, Russia; Imtiaz Ahmed Wani, PhD, Shodi Gali, Amira Kadal, Srinagar, India

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Karvonen J, Gullichsen R, Laine S, Salminen P, Grönroos JM. Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: primary and long-term results from a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1069-1073. |

| 2. | Bujanda L, Calvo MM, Cabriada JL, Orive V, Capelastegui A. MRCP in the diagnosis of iatrogenic bile duct injury. NMR Biomed. 2003;16:475-478. |

| 3. | Bergman JJ, van den Brink GR, Rauws EA, de Wit L, Obertop H, Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN, Gouma DJ. Treatment of bile duct lesions after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gut. 1996;38:141-147. |

| 4. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Tielve M, Hinojosa CA. Acute bile duct injury. The need for a high repair. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1351-1355. |

| 5. | Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, Dellinger EP, Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168-2173. |

| 6. | Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, Hilleren DJ, Johnson RD, Baker ME, Newman GE, Cotton PB, Meyers WC. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;215:196-202. |

| 7. | Lillemoe KD, Martin SA, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Talamini MA, Kaushal S, Coleman J, Venbrux AC, Savader SJ, Osterman FA. Major bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Follow-up after combined surgical and radiologic management. Ann Surg. 1997;225:459-468; discussion 468-471. |

| 8. | Brooks DC, Becker JM, Connors PJ, Carr-Locke DL. Management of bile leaks following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:292-295. |

| 9. | vanSonnenberg E, D'Agostino HB, Easter DW, Sanchez RB, Christensen RA, Kerlan RK Jr, Moossa AR. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: coordinated radiologic and surgical management in 21 patients. Radiology. 1993;188:399-404. |

| 10. | Bismuth H. Postoperative strictures of the bile ducts. The Biliary Tract V. New York, NY: Churchill-Livingstone 1982; 209-218. |

| 11. | Way LW, Stewart L, Gantert W, Liu K, Lee CM, Whang K, Hunter JG. Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries: analysis of 252 cases from a human factors and cognitive psychology perspective. Ann Surg. 2003;237:460-469. |

| 12. | Bektas H, Schrem H, Winny M, Klempnauer J. Surgical treatment and outcome of iatrogenic bile duct lesions after cholecystectomy and the impact of different clinical classification systems. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1119-1127. |

| 13. | Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101-125. |

| 14. | Ahrendt SA, Pitt HA. Surgical therapy of iatrogenic lesions of biliary tract. World J Surg. 2001;25:1360-1365. |

| 15. | Meyers WC, Peterseim DS, Pappas TN, Schauer PR, Eubanks S, Murray E, Suhocki P. Low insertion of hepatic segmental duct VII-VIII is an important cause of major biliary injury or misdiagnosis. Am J Surg. 1996;171:187-191. |

| 16. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Cano-Gutiérrez G, Chaparro JM, Galindo E, Vilatobá M, Samaniego-Arvizu G. To stent or not to stent bilioenteric anastomosis after iatrogenic injury: a dilemma not answered? Arch Surg. 2002;137:60-63. |

| 17. | Mercado MA, Orozco H, de la Garza L, López-Martínez LM, Contreras A, Guillén-Navarro E. Biliary duct injury: partial segment IV resection for intrahepatic reconstruction of biliary lesions. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1008-1010. |

| 18. | Strasberg SM, Picus DD, Drebin JA. Results of a new strategy for reconstruction of biliary injuries having an isolated right-sided component. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:266-274. |

| 19. | Pickleman J, Marsan R, Borge M. Portoenterostomy: an old treatment for a new disease. Arch Surg. 2000;135:811-817. |

| 20. | Savader SJ, Lillemoe KD, Prescott CA, Winick AB, Venbrux AC, Lund GB, Mitchell SE, Cameron JL, Osterman FA Jr. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related bile duct injuries: a health and financial disaster. Ann Surg. 1997;225:268-273. |

| 21. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Tielve M, Contreras A, Gálvez-Treviño R, Ramos-Gallardo G, Orozco H. [Iatrogenic injury of the bile duct. Experience with repair in 180 patients]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2002;67:245-249. |

| 22. | Winslow ER, Fialkowski EA, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG, Picus DD, Strasberg SM. "Sideways": results of repair of biliary injuries using a policy of side-to-side hepatico-jejunostomy. Ann Surg. 2009;249:426-434. |

| 23. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Villalta JM, Barajas-Olivas A, Eraña J, Domínguez I. Long-term evaluation of biliary reconstruction after partial resection of segments IV and V in iatrogenic injuries. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:77-82. |

| 24. | Mercado MA, Orozco H, Chan C, Quezada C, Barajas-Olivas A, Borja-Cacho D, Sánchez-Fernandez N. Bile duct growing factor: an alternate technique for reconstruction of thin bile ducts after iatrogenic injury. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1164-1169. |

| 25. | Mercado MA, Sanchez N, Urencio M. Major hepatectomy for the treatment of complex bile duct injury. Ann Surg. 2009;249:542-543; author reply 543. |

| 26. | de Reuver PR, Busch OR, Rauws EA, Lameris JS, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Long-term results of a primary end-to-end anastomosis in peroperative detected bile duct injury. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:296-302. |