INTRODUCTION

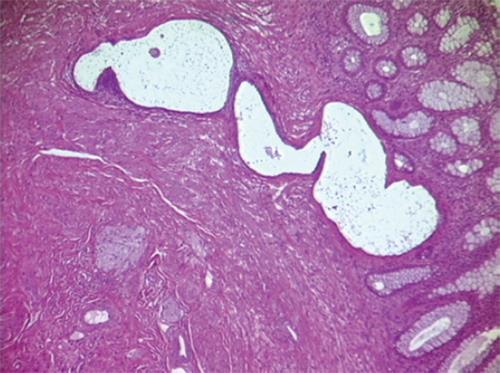

The term bowel endometriosis is used to indicate that endometrial-like gland and stroma infiltrate the intestinal wall reaching at least the subserous fat tissue and the subserous part of the enteric plexus[1] (Figure 1). Endometriotic foci located on the bowel serosa should be considered peritoneal endometriosis and not intestinal endometriosis. The exact prevalence of bowel endometriosis in the general population is unknown, although it is estimated that it affects between 3.8% and 37% of women with endometriosis[1]. The highest frequency of endometriotic nodules is on the sigmoid colon and the rectum, followed by the ileum, the appendix and the cecum[1].

Figure 1 Section of a bowel endometriotic nodule, hemeatoxylin eosin staining demonstrates the nodule infiltrate the mucosa.

SYMPTOMS

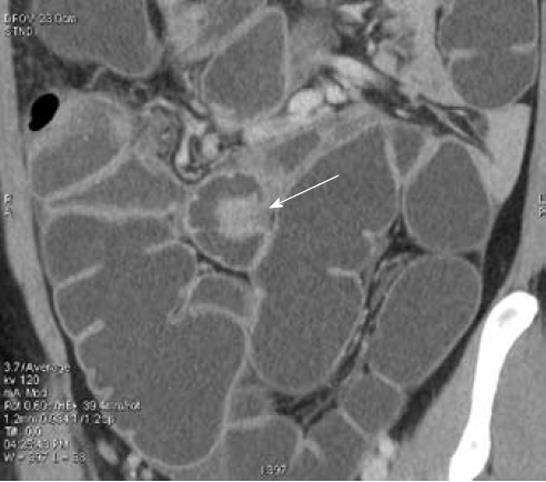

Intestinal endometriotic lesions may have variable size and depth of infiltration in the bowel wall and they may, therefore, cause a wide range of symptoms. In addition, bowel nodules are associated with the presence of other endometriotic lesions in the pelvis in over 99% of patients[2]. As a consequence, it may be difficult to determine whether intestinal endometriosis contributes to abdominal and pelvic pain. In general, small endometriotic lesions reaching only the subserosal fat tissue do not cause symptoms[3]. Larger nodules infiltrating the intestinal muscular layer cause a wide range of symptoms including dyschezia, constipation, diarrhea, abdominal bloating, painful bowel movements, passage of mucus in the stools and cyclical rectal bleeding[3,4]. The symptoms associated with intestinal endometriosis often mimic diarrhea-predominant or constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome[5,6] and this differential diagnosis may be particularly challenging[7]. It remains unclear how bowel endometriosis causes intestinal symptoms. Obviously, large endometriotic nodules may contain extensive fibrosis and thicken the bowel wall, resulting in a stenosis of the intestinal lumen (Figure 2) and perhaps mechanically hampering bowel transit. In addition, intestinal endometriotic lesions infiltrate and disrupt intestinal nervous plexus[3], damage interstitial Cajal cells[3], reduce the density of intestinal sympathetic nerve fibers[8] and thus, cause an alteration in bowel physiology.

Figure 2 Sections of an intestinal endometriotic nodule demonstrating the thickening of the bowel wall caused by the endometriotic nodule.

DIAGNOSIS

Both the evaluation of symptoms and clinical examination are inadequate for an accurate diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis[9,10]. Therefore, ultrasonographic or radiological techniques are required to confirm this diagnosis before surgery[1]. Although no gold standard is universally accepted for the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one of the techniques most commonly used (Figure 3). A study comprising 195 patients with suspected endometriosis demonstrated that MRI has a sensitivity of 88%, a specificity of 98%, a positive predictive value of 95%, a negative predictive value of 95%, and an accuracy of 95% in diagnosing intestinal endometriosis[11]. These findings were subsequently confirmed by several other investigations[9,10,12,13]. However, in some cases, the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis by MRI may be difficult because nodules with small hemorrhagic content have a signal intensity very close to that of the surrounding muscular structures[14]. Therefore, the injection of ultrasonography jelly in the vagina and the rectum during MRI has been proposed to facilitate the identification of intestinal lesions (Figure 4)[15].

Figure 3 Magnetic resonance imaging, T2W sagittal image.

A nodule infiltrating the rectum is well detectable (arrow). Enhancement of the nodule is observed after injection of iodinated contrast medium.

Figure 4 Magnetic resonance imaging enteroclysis.

The rectosigmoid is distended by using 250-300 mL of ultrasonographic gel diluted with saline solution; the 20-Fr Foley catheter used for retrograde distension can be observed in the figure. The fluid solution has a biphasic behavior on MR sequences: hypointense in T1W images and hyperintense in T2W images. A small rectovaginal endometriotic nodule (larger diameter 12 mm) is observed (arrow).

Several studies have demonstrated that transvaginal ultrasonography may not only accurately diagnose the presence of rectosigmoid endometriosis but it may also estimate the depth of infiltration of the nodules in the intestinal wall[16-20]. However, it is well known that the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography depends on the experience of the operator. Adding water contrast to the rectum during transvaginal ultrasonography may facilitate not only the identification of intestinal endometriotic lesions but also the evaluation of the characteristics of the nodules (size, number, depth of infiltration in the intestinal wall, degree of stenosis of the intestinal lumen)[21-23] However, bowel preparation is required before adding water contrast to the rectum.

Double-contrast barium enema has been widely used in the past and remains an accurate technique for the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis[24-30]. Bowel nodules appear as extrinsic masses that are associated with mucosal fine crenulations[26]. The value of this exam is limited by the fact that the degree of infiltration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall cannot be determined.

Multidetector computerized tomography enteroclysis (MDCT-e) has recently been suggested for the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis[31,32]. After bowel preparation, retrograde colonic distension is performed on the computerized tomography bed by introducing about 2000 mL of water. During the enteroclysis, pharmacological inhibition of peristaltic waves is achieved by intravenous injection of hyoscine butylbromide. Patients are examined with a 16-row MDCT scanner in supine position; a volumetric acquisition is performed from the dome of the diaphragm to the pubic symphysis, in portal phase (40 s

after the arterial peak) after the intravenous injection of iodinated contrast medium. MDCT-e allows estimation not only of the presence of intestinal endometriosis but also of the characteristics of the nodules, in particular, the depth of infiltration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall. The infiltration of the intestinal serosa is characterized by the presence of small nodules adjacent to the bowel loop resulting in an irregular intestinal profile; in these nodules, the fat plane between endometriosis and the bowel wall is preserved. When the muscularis propria is infiltrated, MDCT-e allows observation of the multilayered stratification of the thickened bowel wall. Full thickness infiltration of the bowel wall is diagnosed when the solid nodules infiltrate the submucosa (which appears as a hypodense layer between the lumen and the muscularis propria) reaching the intestinal mucosa (Figure 5)[31,32]. A strength of MDCT-e is that it allows detection of endometriotic lesions in the cecum and lower ileal loops which might be undiagnosed by other exams (Figure 6). The major disadvantages of MDCT-e are the use of iodinated contrast medium and ionizing radiations.

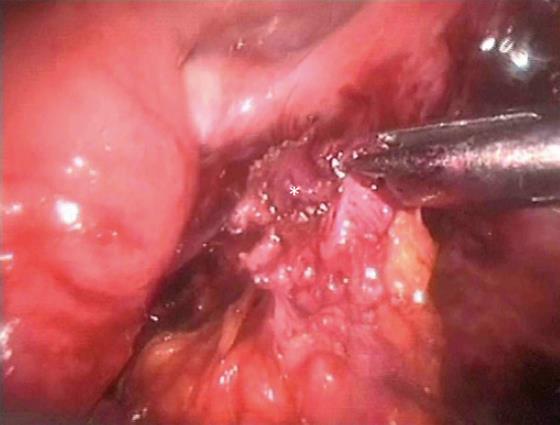

Figure 5 Multidetector computerized tomography enteroclysis, coronal reconstruction.

Endometriotic nodule infiltrating the muscularis propria of the sigmoid (shown by the arrowheads); the mucosa is not infiltrated.

Figure 6 Multidetector computerized tomography enteroclysis, the arrow shows an endometriotic nodule infiltrating the ileum.

Rectal endoscopic ultrasonography has been widely used for the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis[12,33-34]. This exam permits to estimation of the precise depth of infiltration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall (in particular, the infiltration of the muscularis propria), the maximum diameter of the lesions and the distance of the lesions from the anus[1]. In the last few years, rectal endoscopic ultrasonography has been largely replaced by transvaginal ultrasonography which is better tolerated by the patients. In addition, the equipment for performing rectal endoscopic ultrasonography is often unavailable to gynecologists, the clinicians who are commonly involved in the diagnosis and management of endometriosis.

Colonoscopy has limited value in the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis because the disease infiltrates the intestinal wall from the serosa toward the mucosa and, therefore, only large nodules infiltrating the mucosa and/or

causing a severe stenosis of the intestinal lumen can be diagnosed during this type of exam[1]. In rare cases, colonoscopy may be used to exclude the presence of colorectal cancer.

MANAGEMENT OF BOWEL ENDOMETRIOSIS

The management strategy for bowel endometriosis depends on the size of the nodule, the degree of stenosis of the intestinal lumen and the symptoms experienced by the patients. In a small percentage of women, intestinal endometriotic lesions do not cause symptoms and, therefore, these patients may not receive treatment. However, in these patients, the thickening of the bowel lumen (leading to intestinal stenosis) should be evaluated in order to exclude the risk of bowel occlusion. Larger endometriotic nodules causing intestinal symptoms may be treated by hormonal therapy or by surgery.

MEDICAL TREATMENT OF BOWEL ENDOMETRIOSIS

Hormonal therapy cannot be offered to all women with intestinal endometriosis. Patients with intestinal nodules causing a bowel stenosis and those wishing to conceive are not good candidates for long-term endocrine therapy, which inhibits ovulation. The available ultrasonographic and radiological techniques allow accurate estimation of the presence, number and depth of infiltration of intestinal endometriotic lesions; hormonal therapy may be safely offered to women with estimated bowel stenosis of < 60%.

Hormonal therapies commonly used to treat pelvic endometriosis can generally be prescribed to women with bowel endometriosis. In the past, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRH-a) have occasionally been used to treat patients with bowel endometriosis[35]. However, most authors simply report the recurrence of pain symptoms when the therapy with GnRH-a was discontinued[36,37]. In one case report, the disappearance of an intestinal endometriotic polyp was reported after 3-mo treatment with GnRH-a[38]. More recently, a prospective study systematically investigated the effects of a 12-mo treatment with triptorelin and tibolone on pain and intestinal symptoms in 18 women with colorectal endometriotic nodules[39]. As expected, the treatment improved pain symptoms. In addition, it significantly reduced the severity of symptoms mimicking diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, intestinal cramping, abdominal bloating and passage of mucus with stools. On the contrary, seven women with symptoms mimicking constipation- predominant irritable bowel syndrome reported only minor changes in their intestinal symptoms[39].

Progestins are among the most commonly used medical treatments for endometriosis. Several studies have proved that these agents effectively reduce the severity of symptoms caused by pelvic endometriosis and are in general well tolerated[40]. One prospective study examined the effects of progestins on the symptoms caused by intestinal endometriosis[41]. Forty symptomatic women with colorectal endometriosis were treated with norethisterone acetate (2.5 mg/d) for 12 mo. This reduced the severity of chronic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia and dyschezia. As expected, the treatment resulted in the disappearance of symptoms related to the menstrual cycle such as dysmenorrhea, constipation during the menstrual cycle, diarrhea during the menstrual cycle and cyclical rectal bleeding. The severity of diarrhea, intestinal cramping and passage of mucus significantly improved during treatment. However, the administration of norethisterone acetate did not produce a significant effect on constipation, abdominal bloating and feeling of incomplete evacuation after bowel movements. More recently, aromatase inhibitors have been suggested for the treatment of endometriosis[42]. A prospective pilot study comprising six women with colorectal endometriosis demonstrated that pain and intestinal symptoms are improved by the combined administration of an aromatase inhibitor (letrozole, 2.5 mg/d) and norethisterone acetate (2.5 mg/d) continuously for 6 mo[43].

Although hormonal therapies may improve the symptoms caused by intestinal endometriosis, the natural history of bowel nodules is not established. It is well known that patients undergoing surgery because of extensive intestinal endometriotic lesions have often used hormonal therapies for years. Therefore, it is possible that hormonal therapies, despite improving symptoms, do not prevent the development or progression of intestinal endometriosis. A recent report described the case of a woman with a diagnosis of an endometriotic serosal sigmoid nodule at MDCT-e which enlarged after 41 mo of continuous oral contraceptive pill, infiltrating the bowel submucosa and requiring segmental bowel resection[44]. Therefore, patients using long-term hormonal therapies to treat intestinal endometriosis should be carefully monitored by using transvaginal ultrasonography or MRI in order to identify the potential progression of intestinal nodules. In addition, these patients should be informed that the progression of the disease might occur despite the improvement in pain symptoms.

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF BOWEL ENDOMETRIOSIS

Small endometriotic lesions infiltrating only the intestinal serosa or the adventitia are unlikely to cause symptoms and may, therefore, not be excised. However, they can be easily removed by cutting the normal bowel wall adjacent to the lesion with scissors or CO2 laser. The defect of the intestinal wall can then be repaired by interrupted suture.

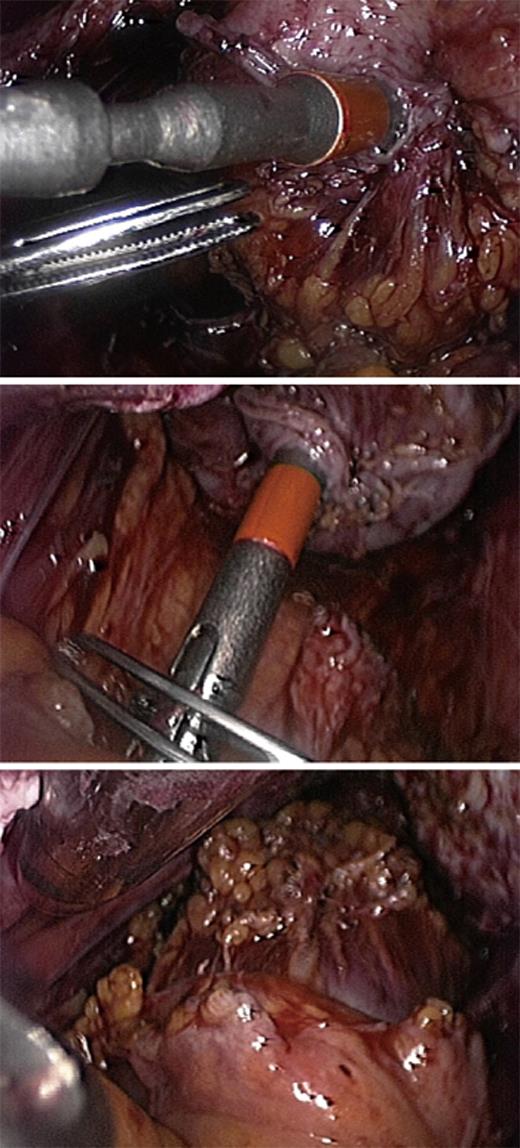

Larger colorectal endometriotic nodules infiltrating the intestinal muscularis propria can be excised by either nodulectomy (partial or full thickness) (Figure 7) or segmental bowel resection. The choice of the surgical technique is based partly on the characteristics of the intestinal lesions such as, number of nodules, size of the nodules, depth of infiltration of the intestinal wall and percentage of the intestinal circumference infiltrated by endometriosis. However, surgeon’s experience and preferences also influence the decision to perform either bowel segmental resection or nodulectomy.

Figure 7 Nodulectomy, the endometriotic nodule is shown by the asterisk.

Colorectal resection which is a standardized surgical procedure that has been used for decades for the treatment of sigmoid or rectal cancer is similarly performed (most often by laparoscopy) in women with endometriosis. The endometriotic nodule is separated from the adherent tissues, but no attempt is made to separate the nodule from the bowel. Bowel preparation requires opening the pararectal spaces in order to mobilize the bowel. As endometriosis is not a malignant disease, the separation of the fibrofatty tissue attached to the bowel is best performed immediately adjacent to the bowel wall because the vessels are smaller and easier to coagulate. The mesentery is dissected no more than 2 cm past the endometriotic lesions in order to maintain adequate blood supply to the edges of the anastomosis[1]. After the bowel is resected caudal to the endometriotic lesion by using Endo GIA, the proximal portion of the bowel is extracted through a small sovrapubic incision. After accurate inspection and palpation, the bowel segment infiltrated by endometriosis is resected. The anvil of a transanal circular stapler is inserted into the proximal bowel stump and fixed by a purse-string suture. An end-to-end anastomosis is performed transrectally using a mechanic circular stapler (Figure 8). After completing the anastomosis, the possible presence of leaks must always be checked. In patients with endometriosis, the most important argument in favor of segmental bowel resection is the fact that this technique allows a more radical removal of intestinal endometriotic foci, thus minimizing the risk of recurrences. Over the last 10 years, several studies have showed that, in women with colorectal endometriosis, segmental bowel resection improves pain, intestinal symptoms and quality of life[12,45-48]. However, segmental resection may be associated with several complications including urinary retention, inadvertent ureteral lesions, anastomosis leakage and fecal peritonitis, rectovaginal fistulas, anastomotic stenosis, pelvic abscesses and postoperative constipation[1,30,46]. Segmental bowel resection can be performed either by laparoscopy or by laparotomy. During segmental colorectal resection because of bowel endometriosis, the reported conversion rates from laparoscopy to laparotomy range from 0% to 20%[49,50]. A recent randomized trial comparing laparoscopic and open colorectal resection for endometriosis demonstrated that the two surgical techniques result in a similar improvement in symptoms and quality of life[49]. However, blood loss, analgesic consumption and complication rate were higher in patients undergoing open surgery than in those undergoing laparoscopy[49].

Figure 8 A mechanic circular stapler inserted transrectally is used to perform an end-to-end anastomosis.

It is currently debated whether bowel endometriosis should be removed by segmental resection or by nodulectomy. A prospective surgical and histological study evaluated the completeness of full thickness disk resection[46]. In 16 women requiring segmental bowel resection, nodulectomy was performed before segmental resection. In 7 out of 16 cases (43.8%), endometriosis was still present in the muscularis propria adjacent to the site of nodulectomy. A similar rate of persistent disease was observed after laparoscopic and laparotomic full thickness disc resection[51]. However, the clinical implications of these observations remain unclear because it seems unlikely that small endometriotic lesions will cause symptoms or progress to large intestinal nodules. In addition, in segmental resection, persistence of endometriosis may also be observed at the margin of the resected intestinal segment[51]. A recent study of 500 women with deep endometriosis and rectal muscularis involvement demonstrated that, after laparoscopic nodulectomy, symptoms recurred only in 8% of the patients after a median follow-up of 3.1 years[30]. In addition, the recurrence of symptoms was significantly lower in patients who conceived after surgery than in those who did not conceive[30]. When compared with segmental bowel resection, nodulectomy may have the advantage of a lower incidence of postoperative unpleasant functional digestive outcomes (such as increase in the daily number of stools, severe postoperative constipation and urinary dysfunction)[52]. In fact, during nodulectomy, nerves and vascular blood supply are preserved because it is not necessary to perform the deep lateral dissection that is required during segmental resection[30,52]. Similarly, after segmental bowel resection, the full recovery of gastrointestinal function can usually be observed several months after surgery[53].

FERTILITY AFTER SURGERY FOR BOWEL ENDOMETRIOSIS

Several studies have showed that good pregnancy rates are achieved after surgical excision of intestinal endometriosis. A retrospective study of 22 women wishing to conceive reported a 45.5% pregnancy rate after a mean follow-up of 24 mo from laparoscopic colorectal resection[54]. Subsequently, a prospective cohort study of 46 symptomatic women undergoing colorectal resection because of endometriosis showed that the pregnancy rate was significantly higher after laparoscopic (57.6%) than after laparotomic procedures (23.1%)[55]. More recently, a study of 288 women wishing to conceive demonstrated that nodulectomy is associated with an 84% pregnancy rate (obtained either naturally or after assisted reproductive technologies) after a median follow-up of 3.1 years[30].

CONCLUSION

The symptoms of bowel endometriosis are not specific, therefore its presence should be suspected in all women with endometriosis who complain of intestinal symptoms. Transvaginal ultrasonography is the first line investigation for patients with suspected bowel endometriosis as it allows to accurate determination of the presence of the disease[19,20,22]. Additional radiological techniques (such as MRI and MDCT-e) are useful to determine the extent of intestinal endometriotic lesions[11,31].

The management of bowel endometriosis depends on the severity of symptoms, the extent of the disease, the desire of the patient to conceive and the tolerability of hormonal therapies. Progestins and gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues may be offered to women with stenosis of the bowel lumen < 60% who wish to avoid surgery and do not desire to conceive[39,41]. However, hormonal therapies may not prevent the progression of bowel endometriosis[44] and, therefore, patients receiving long-term treatment should be periodically monitored.

The decision to carry out surgery should be undertaken in selected patients, such as those who are highly symptomatic, have a severe stenosis of the intestinal lumen or cannot use hormonal therapies because of the desire to conceive. Intestinal endometriotic lesions can be excised by either segmental resection or nodulectomy; it remains to be established whether one surgical technique is superior to the other. However, before surgery patients should be fully informed of potential complications including the time required to obtain a full recovery of the digestive function.

Peer reviewer: Imtiaz Ahmed Wani, PhD, Shodi Gali, Amira Kadal, Srinagar, India

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM