Published online Oct 27, 2011. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v3.i10.147

Revised: October 17, 2011

Accepted: October 22, 2011

Published online: October 27, 2011

AIM: To compare hemorrhoidectomy with a bipolar electrothermal device or hemorrhoidectomy using an ultrasonically activated scalpel.

METHODS: Sixty patients with grade III or IV hemorrhoids were prospectively randomized to undergo closed hemorrhoidectomy assisted by bipolar diathermy (group 1) or hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel (group 2). Operative data were recorded, and patients were followed at 1, 3, and 6 wk to evaluate complications. Independent assessors were assigned to obtain postoperative pain scores, oral analgesic requirement and satisfaction scores.

RESULTS: Reduced intraoperative blood loss median 0.9 mL (95% CI: 0.8-3.7) vs 4.6 mL (95% CI: 3.8-7.0), P = 0.001 and a short operating time median 16 (95% CI: 14.6-18.2) min vs 31 (95% CI: 28.1-35.3) min, P < 0.0001 was observed in group 1 compared with group 2. There was a trend towards lower postoperative pain scores on day 1 group 1 median 2 (95% CI: 1.8-3.5) vs group 2 median 3 (95% CI: 2.6-4.2), P = 0.135. Reduced oral analgesic requirement during postoperative 24 h after operation median 1 (95% CI: 0.4-0.9) tablet vs 1 (95% CI: 0.9-1.3) tablet, P = 0.006 was observed in group 1 compared with group 2. There was no difference between the two groups in the degree of patient satisfaction or number of postoperative complications.

CONCLUSION: Bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy is quick and bloodless and, although as painful as closed hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel, is associated with a reduced analgesic requirement immediately after operation.

- Citation: Tsunoda A, Sada H, Sugimoto T, Kano N, Kawana M, Sasaki T, Hashimoto H. Randomized controlled trial of bipolar diathermy vs ultrasonic scalpel for closed hemorrhoidectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2011; 3(10): 147-152

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v3/i10/147.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v3.i10.147

Hemorrhoidectomy is the treatment of choice for patients with symptomatic grade III and IV hemorrhoids. Although the operation is considered a minor procedure, the postoperative course is protracted and painful. Recent advances in instruments that include a bipolar electrothermal device[1], ultrasonic scalpel[2], and circular stapler[3] have provided effective alternatives, resulting in less postoperative pain and perioperative blood loss.

A bipolar electrothermal device (Ligasure™, Valleylab, Boulder, CO) is a novel hemostatic device and can deliver the precise amount of electrocautery energy across the vascular structures with minimal surrounding thermal spread. Hemorrhoidectomy with a bipolar diathermy has been shown to reduce operating time and postoperative pain or analgesic requirements[4,5]. An ultrasonic activated scalpel (Harmonic Scalpel™, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Puerto Rico) is associated with decreased thermal damage to tissue, superior wound healing, and facilitated dissection within tissue planes[6]. Hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel has been shown to be an effective, safe method for hemorrhoid excision[7] with the additional benefit of reduced postoperative pain[2]. Recently, bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy was reported to reduce postoperative pain compared to open hemorrhoidectomy using the ultrasonic scalpel[8]. Bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy is considered as a sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy, since the “tissue sealing zone” is just transected[1,9]. This prompted a prospective evaluation of postoperative pain and analgesic requirements after bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy vs closed hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel.

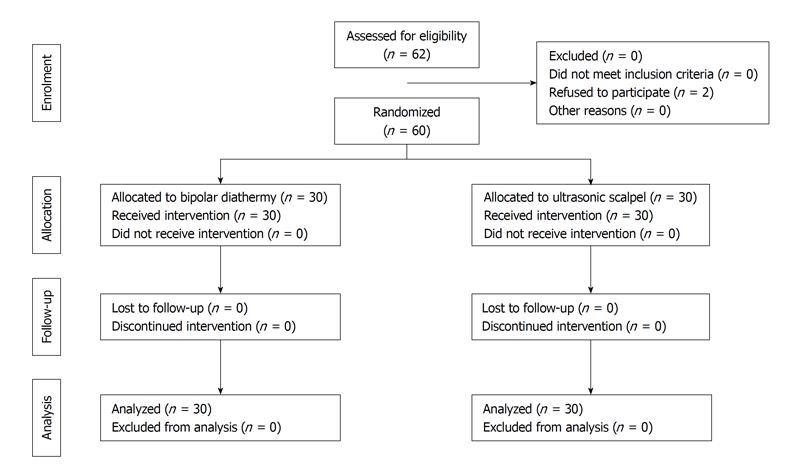

Between February 2010 and December 2010, 62 patients with symptomatic grade III and IV hemorrhoids were recruited to the trial according to the profile in Figure 1. Patients who refused to be randomized were excluded. Approval of the local ethics committee had been obtained. Exclusion criteria included the use of regular immunosuppressants or analgesics, patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists grade III and IV, pregnancy, previous anal surgery, and inability to give written informed consent. Primary endpoints included the analgesic requirements and postoperative pain score. Secondary endpoints included the operating time, blood loss, hospital stay, patient satisfaction score, and early and late complications. Patient demographics and symptoms were recorded. Patients were first stratified according to sex and age (< 60 years vs≥ 60 years) and then randomly assigned to either group 1 (bipolar diathermy) or group 2 (ultrasonic scalpel) using the permuted block method at the time of anesthesia. The patients were blind to the treatment that they were to undergo.

Under spinal anesthesia, patients were placed in a prone jackknife position. A mixture of lidocaine 0.5% and adrenaline 1:200 000 was infiltrated into the subcutaneous and submucosal planes to elevate the hemorrhoidal pedicles from the underlying anal sphincter muscle. A senior surgeon (AT) was present at all surgeries to ensure that the same technique was used and the inclusion criteria were observed. Higher surgical trainees performed the procedures. A hemostatic sponge was inserted into the anal canal after complete excision of hemorrhoids.

In group 1, the power of the system was set at level 2. A self-retaining anal retractor was used to exposure the hemorrhoids. The diathermy forceps were applied across the skin tags, then the hemorrhoids, and finally the pedicles. Completion of coagulation was signaled by the feedback sensors, and hemorrhoidal tissue was excised along the line of coagulation. Repeated applications of the bipolar diathermy were performed, as necessary, for complete hemorrhoidal excision. In group 2, the power of the system was set at level 3. The ultrasonic scalpel was applied across the skin tags and the hemorrhoids. Pedicle control was achieved using the same device. Wounds were closed with a continuous 4-0 Polyglactin suture.

Normal diet was allowed, and a magnesium laxative [Magmit™ (0.3 mg) (Nihon Shinyaku Co., Kyoto, Japan) 6 tablets per day] was prescribed after surgery. The patient was instructed to irrigate the anal wound with clean water at least three times a day and after every bowel movement. For pain relief, Loxonine™ (Daiichi Sankyo Co., Tokyo, Japan) (one tablet, four times a day on demand) was given orally. Intravenous flurbiprofen axetil (50 mg) was given on demand every 6 h. The patient was discharged from the hospital once the following criteria were met: (1) no significant postoperative complications; (2) no fever; and (3) intravenous flurbiprofen axetil administration no longer required. Pain scores, analgesic requirements, the operating time, blood loss, days to first bowel movement, complications, and length of stay were recorded. Pain scores were evaluated using a numeric rating scale (0-10).

Patients were followed up 1, 3 and 6 wk after surgery. Wound healing and late complications were documented. Postoperative swelling of wounds was evaluated by the inspection of the anal canal 1 wk after surgery. Two grades were defined as “negative” (no swelling or swelling are less than 1 cm × 1 cm) and “positive” (swelling are larger than 1 cm × 1 cm) as previously reported[9]. The independent assessors were blind to the results of randomization evaluated pain scores and recorded analgesic requirements both preoperatively and on postoperative Days 1 to 7, and at 3 and 6 wk by telephone follow-up. The patient satisfaction score was also obtained by the independent assessors at 6 wk. The score ranged from -3 to +3, with -3 being very dissatisfied and +3 being very satisfied with the outcome of the operation.

At least 20 patients were needed in each group to detect a difference of one standard deviation in mean analgesic requirement, with an 80% power at a 5% level of significance. All data analyses were performed using the SPSS™ statistical software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and categoric variables using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Results are expressed as the median unless otherwise specified.

Sixty patients were randomized to the trial. Adequacy of randomization was demonstrated by the similarity in patient characteristics in both groups (Table 1). No protocol violations were recorded throughout the study. The median number of hemorrhoids excised was similar between the groups (Table 2). Median (range) operating time was significantly shorter in group 1 [16 (9-28) min, 95% CI: 14.6-18.2 min] than in group 2 [(31 (14-58) min, 95% CI: 28.1-35.3 min)], P < 0.0001. The median (range) intraoperative blood loss was significantly less in group 1 than in group 2 [0.9 (0-20) mL, 95% CI: 0.8-3.7 mL vs 4.6 (0-15), 95% CI: 3.8-7.0 mL, P = 0.001]. The median (range) number of oral analgesic tablets consumed was 12.5 (0-75) (95% CI: 11.7-25.3) by patients in group 1 and 13.5 (0-64) (95% CI: 10.1-21.8) by patients in group 2. There was no significant difference in oral analgesic usage between the two groups. However, during the postoperative 24 h, usage was significantly less in group 1 than group 2 [1 (0-2), 95% CI: 0.4-0.9 vs 1 (0-2), 95% CI: 0.9-1.3], P = 0.006. Altogether, 60% of patients in group 1 required analgesics compared to 90% in group 2. Moreover, although no patient required flurbiprofen axetil injections in group 1, one patient required 1 injection, and the other patient required 2 injections during the postoperative 24 h in group 2. The duration of the hospital stay, the time to first bowel motion, and patient satisfaction score were similar between the two groups. Analysis of the postoperative pain scores revealed a trend toward less discomfort on day 1 in group 1 patients, although this was not statistically significant [2 (0-8), 95% CI: 1.8-3.5 vs 3 (0-8), 95% CI: 2.6-4.2, P = 0.135]. Subsequently, the recorded pain scores of the two groups converged, with a gradual reduction to day 7 (Table 3).

| Group 1 | Group 2 | P | |

| No. of patients | 30 | 30 | |

| Nedian (range) age (yr) | 63 (3-85) | 63 (27-84) | 0.646 |

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 16:14 | 16:14 | 1.000 |

| Grade | 0.598 | ||

| III | 17 | 19 | |

| IV | 13 | 11 |

| Parameter | Group 1 (n = 30) | Group 2 (n = 30) | P |

| No. of hemorrhoids resected, median (range) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0.548 |

| 2 | 8 | 9 | |

| 3 | 18 | 19 | |

| 4 | 4 | 2 | |

| Operating time (95% CI, min) | 16 (14.6-18.2) | 31 (28.1-35.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Blood loss (95% CI, mL) | 0.9 (0.8-3.7) | 4.6 (3.8-7.0) | 0.001 |

| Oral analgesics use (tablets) (95% CI, 24 h) | 1 (0.4-0.9) | 1 (0.9-1.3) | 0.006 |

| Hospital stay (95% CI, d) | 2 (2.1-2.7) | 2 (2.2-2.8) | 0.275 |

| First defecation (95% CI, postoperative day) | 1 (1.1-1.7) | 1 (1.2-1.8) | 0.883 |

| Satisfaction (95% CI, -3 to +3) | 3 (1.9-2.8) | 3 (1.9-2.7) | 0.931 |

| Time point | Group 1 (n = 30) | Group 2 (n = 30) | P |

| Preoperative | 0 (0.1-1.0) | 0 (0.0-1.1) | 0.303 |

| POD 1 | 2 (1.8-3.5) | 3 (2.6-4.2) | 0.135 |

| POD 2 | 2 (1.8-3.3) | 2.5 (1.9-3.3) | 0.690 |

| POD 3 | 2 (1.6-2.3) | 2.5 (1.9-3.1) | 0.484 |

| POD 4 | 2 (1.4-2.7) | 2 (1.6-3.0) | 0.602 |

| POD 5 | 2 (1.3-3.0) | 2 (1.3-2.6) | 0.988 |

| POD 6 | 2 (1.5-2.9) | 2 (1.5-2.9) | 0.976 |

| POD 7 | 1 (1.1-2.4) | 2 (1.3-2.5) | 0.416 |

| POW 3 | 0 (0.4-1.2) | 0 (0.3-1.1) | 0.665 |

| POW 6 | 0 (0.1-0.9) | 0 (0.0-0.4) | 0.399 |

Postoperative complications are listed in Table 4. Urinary retention was present in two patients (6.7%) in group 1 and in five (16.7%) in group 2. Wound edema at 1 wk after operation occurred in five (16.7%) group 1 and in six (20.0%) in group 2. One patient in group 2 experienced reactive hemorrhage requiring hospital admission. Impaired wound healing at 6 wk after operation was present in two (6.7%) in group 1 and one (3.3%) in group 2. Complete wound healing was achieved in two of the three patients at 12 wk after operation. The remaining patient in group 1 developed anal fissure, which did not respond to the treatment with stool softners and topical diltiazem paste for 6 mo. None of the patients complained of anal stenosis, flatus incontinence, and recurrent symptoms at the end of 6 wk of follow up.

| Group 1 (n = 30) | Group 2 (n = 30) | P | |

| Urinary retention | 2 | 5 | 0.424 |

| Wound edema (at 1 wk) | 5 | 6 | 0.330 |

| Hemorrhage | 0 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Anal stenosis (at 6 wk) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Flatus incontinence (at 6 wk) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Impaired wound healing (at 6 wk) | 2 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Recurrence (at 6 wk) | 0 | 0 | - |

Hemorrhoidectomy is the most effective and definitive treatment for prolapsed hemorrhoids. Nevertheless, pain after conventional excision hemorrhoidectomy continues to be a major problem. Various techniques have been developed with the aim of reducing postoperative pain. A bipolar electrothermal device delivers optimal electrocautery energy across the diathermy forceps, which ensures the combination of localized coagulation with minimal thermal spread, compared with electrocautery instruments[10]. The ultrasonically activated scalpel divides tissue using high-frequency ultrasonic energy. Because the instrument operates at temperature less than 100°C, it is associated with less undesirable tissue desiccation, char formation and zone of thermal injury compared with electrocautery instruments[6]. Either system may contribute to lower postoperative pain.

This study failed to demonstrate a significant reduction in postoperative pain after bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy. However, the analgesic requirement during 24 h after bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy was significantly lower than that after surgery using the ultrasonic scalpel and no patient required flurbiprofen axetil injections after bipolar diathermy surgery. Kwok et al[8] reported that the postoperative pain was less after bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy than hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel, where the wounds were left open. Because bipolar diathermy surgery is considered as a sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy[1,9] and the wounds were closed in the ultrasonic scalpel group in the present study, treatment of wounds seemed to be identical in both groups. There was some evidence that closed hemorrrhoidectomy was associated with less pain compared with open controls during the early postoperative period[11,12] and this may explain why no significant difference in postoperative pain was observed between the two groups in the present study.

The early and delayed complication rates of either surgery were comparable to those for conventional hemorrhoidectomy, and no serious complications were noted. Urinary retention experienced by the patients treated with a bipolar diathermy or the ultrasonic scalpel occurred with an incidence similar to that found after conventional operations. This complication might be influenced by the regional anesthesia. The troublesome late anal stenosis that occurs following conventional hemorrhoidectomy seems to have been eliminated. As with any technique for the treatment of hemorrhoids, preservation of anal sphincter is extremely important. With the use of adequate tissue retraction and submucosal infiltration, the hemorrhoidal plexus can be readily elevated off the underlying anal sphincter, allowing for safe application of either the diathermy forceps or the blades of the ultrasonic scalpel. Stapled hemorrhoidectomy was reported to be a less painful procedure than bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy, but the latter was a more radical operation[13], without serious complications including pelvic sepsis, anastomotic stenosis, fecal incontinence, and rectovaginal fistula[14].

Although the ultrasonic scalpel has the same advantage of producing less-lateral thermal injury, bipolar diathermy surgery required a shorter operating time, which was consistent with the previous studies[1,5,9,15] and can be explained by the effective hemostatic control with a bipolar diathermy. The operating time for hemorrhoidectomy by the ultrasonic scalpel was reported to be longer than that required for electrocoagulation and conventional surgery, mainly because the hemostasis required after surgery using the ultrasonic scalpel was more time consuming[2,7]. In the present study, an additional procedure of closing wound in patients treated with the ultrasonic scalpel seemed more time consuming than bipolar diathermy surgery.

The disadvantage with either system is the expense incurred. The list price of the disposable electrode of the bipolar diathermy system (LS3111 mode) is approximately $224 and that of the disposable hand piece of the ultrasonic scalpel system (CS14C mode) is approximately $790 and represents a direct addition to the cost of the procedure.

The present study has several limitations. The number of patients was small and our follow-up period was short. The long-term results and recurrence rate should be evaluated in larger prospective studies.

In summary, bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy is quick and bloodless and, although as painful as closed hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel, is associated with a reduced analgesic requirement immediately after the operation.

The authors thank Yuka Kobori and Mugumi Oonishi (pharmacists) for evaluating pain score, analgesic requirements and patient satisfaction score.

Hemorrhoidectomy is the treatment of choice for patients with symptomatic grade III and IV hemorrhoids. Although the operation is considered a minor procedure, the postoperative course is protracted and painful. Hemorrhoidectomy with either a bipolar diathermy or an ultrasonic scalpel has been shown to reduce postoperative pain or analgesic requirements. Recently, bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy was reported to reduce postoperative pain compared to open hemorrhoidectomy using the ultrasonic scalpel.

Bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy is considered as a sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy, since the “tissue sealing zone” is just transected. This prompted a prospective evaluation of postoperative pain and analgesic requirements after bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy vs closed hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel.

Bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy is quick and bloodless and, although as painful as closed hemorrhoidectomy with the ultrasonic scalpel, is associated with a reduced analgesics requirement immediately after operation.

Bipolar diathermy hemorrhoidectomy may be applicable in higher risk patients who need a shorter operating time and a reduced analgesic requirement.

A bipolar electrothermal device (Ligasure™, Valleylab, Boulder, CO) is a novel hemostatic device and can deliver the precise amount of electrocautery energy across the vascular structures with minimal surrounding thermal spread. An ultrasonic activated scalpel (Harmonic Scalpel™, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Puerto Rico) is associated with decreased thermal damage to tissue and facilitated dissection within tissue planes.

The study was well-designed and the results were compatible with previous studies as the authors discussed. Interpretation of the data was reasonable. This paper provides some useful information on this field.

Peer reviewers: Imtiaz Ahmed Wani, PhD, Shodi Gali, Amira Kadal, Srinagar, India; Tsuyoshi Konishi, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Cancer Institute Hospital, 3-10-6 Ariake, Koto-ku, Tokyo 135-8550, Japan

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Sayfan J, Becker A, Koltun L. Sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy: a new technique. Ann Surg. 2001;234:21-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Armstrong DN, Ambroze WL, Schertzer ME, Orangio GR. Harmonic Scalpel vs. electrocautery hemorrhoidectomy: a prospective evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:558-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Rowsell M, Bello M, Hemingway DM. Circumferential mucosectomy (stapled haemorrhoidectomy) versus conventional haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:779-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Franklin EJ, Seetharam S, Lowney J, Horgan PG. Randomized, clinical trial of Ligasure vs conventional diathermy in hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1380-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Palazzo FF, Francis DL, Clifton MA. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasure versus open haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:154-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McCarus SD. Physiologic mechanism of the ultrasonically activated scalpel. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Khan S, Pawlak SE, Eggenberger JC, Lee CS, Szilagy EJ, Wu JS, Margolin M D DA. Surgical treatment of hemorrhoids: prospective, randomized trial comparing closed excisional hemorrhoidectomy and the Harmonic Scalpel technique of excisional hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:845-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kwok SY, Chung CC, Tsui KK, Li MK. A double-blind, randomized trial comparing Ligasure and Harmonic Scalpel hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:344-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chung YC, Wu HJ. Clinical experience of sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy with LigaSure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tan EK, Cornish J, Darzi AW, Papagrigoriadis S, Tekkis PP. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes of randomized controlled trials of LigaSure vs conventional hemorrhoidectomy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1209-118; discussion 1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | You SY, Kim SH, Chung CS, Lee DK. Open vs. closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:108-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McConnell JC, Khubchandani IT. Long-term follow-up of closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:797-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Basdanis G, Papadopoulos VN, Michalopoulos A, Apostolidis S, Harlaftis N. Randomized clinical trial of stapled hemorrhoidectomy vs open with Ligasure for prolapsed piles. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:235-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oughriss M, Yver R, Faucheron JL. Complications of stapled hemorrhoidectomy: a French multicentric study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:429-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jayne DG, Botterill I, Ambrose NS, Brennan TG, Guillou PJ, O'Riordain DS. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasure versus conventional diathermy for day-case haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:428-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |