Published online Sep 27, 2010. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i9.291

Revised: September 15, 2010

Accepted: September 22, 2010

Published online: September 27, 2010

Gastroduodenal artery (GDA) aneurysm rupture is a rare serious condition. The diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion with specific attention to warning signs. Early diagnosis can prevent fatal outcomes. In this report, we describe a case of GDA aneurysm rupture presenting as recurrent syncope and atypical back and abdominal discomfort. The rupture manifested as hemorrhagic shock. The diagnosis was made by computed tomography of the abdomen which showed acute peritoneal and retroperitoneal bleeding. Angiographic intervention failed to coil the GDA and surgery with arterial ligation was the definitive treatment.

- Citation: Harris K, Chalhoub M, Koirala A. Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm rupture in hospitalized patients: An overlooked diagnosis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 2(9): 291-294

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v2/i9/291.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v2.i9.291

Gastroduodenal artery (GDA) aneurysms are extremely rare, potentially serious conditions. They account for about 1.5% of all visceral arterial aneurysms which by themselves represent rare conditions with a reported incidence of 0.01% to 0.2% at best[1].

GDA aneurysm is usually diagnosed by ultrasound (US), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), computed tomography (CT) or angiography depending on the presenting clinical scenario.

We describe a case of GDA aneurysm with onset of warning signs and symptoms 2 d prior to rupture with massive intra-abdominal bleed and resulting hemorrhagic shock.

A 64-year-old man was hospitalized 2 d post elective total knee replacement for recurrent syncopal episodes. His cardiac workup was negative on the telemetry floor with a negative echocardiogram and no evidence of arrhythmias. He was transferred to a rehabilitation ward 2 d later. The patient was doing very well with physical therapy and his knee pain was controlled using acetaminophen and opioids as needed. He was complaining of some back pain and mild epigastric discomfort with a negative physical exam. The patient has no significant past medical history and no previous surgeries. His social history was negative except for a remote smoking history and occasional alcohol use. The patient was on Coumadin postoperatively for DVT prophylaxis with therapeutic INR.

On his second day of rehabilitation, rapid response was called after he was found unresponsive in his chair. His blood pressure was undetectable with a regular heart rate at 120 per minute. Physical exam showed tender bilateral flanks with mild abdominal distension. INR was 2.9 and Hg was 9.8. Hg level was 11.3 five days prior to this event. Prior to this event and at all times, his vitals were stable with no tachycardia and normal blood pressure readings.

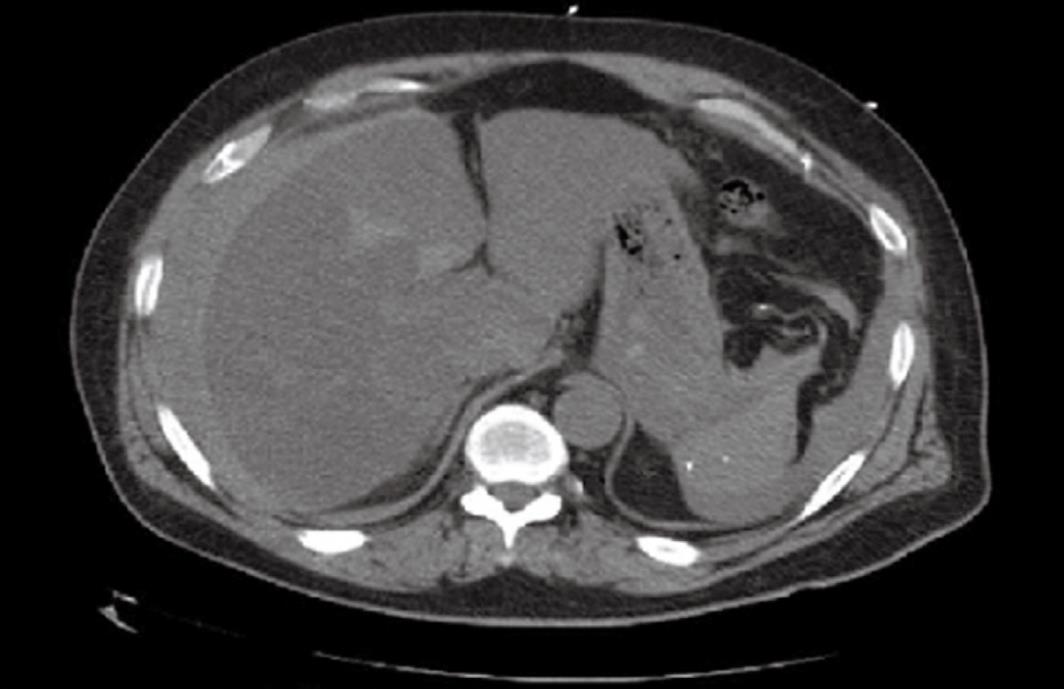

The management started with hemodynamic resuscitation with aggressive intravenous fluid management. He was given vitamin K intravenously and 4 units of FFPs were transfused immediately. The patient was transferred to the critical care unit with the diagnosis of hemorrhagic shock secondary to intra-abdominal bleed. CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis was ordered and done after hemodynamic stabilization (Figure 1). In addition to the below findings, there was an extensive inflammatory change surrounding the duodenum and pancreatic head that suggested these locations as the bleeding source.

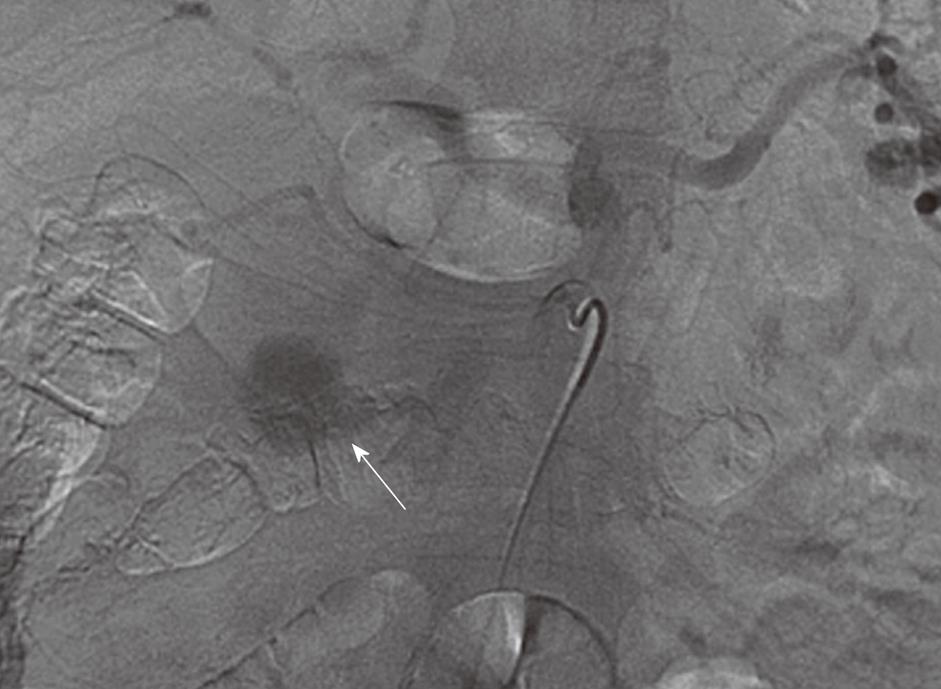

The CT abdomen/pelvis was repeated the next day with IV contrast (Figure 2). It showed a retroperitoneal aneurysm suspected to be arising from the gastroduodenal artery or one of its branches. There was evidence of a retroperitoneal bleed in addition to the intraperitoneal bleed shown on previous CT scan.

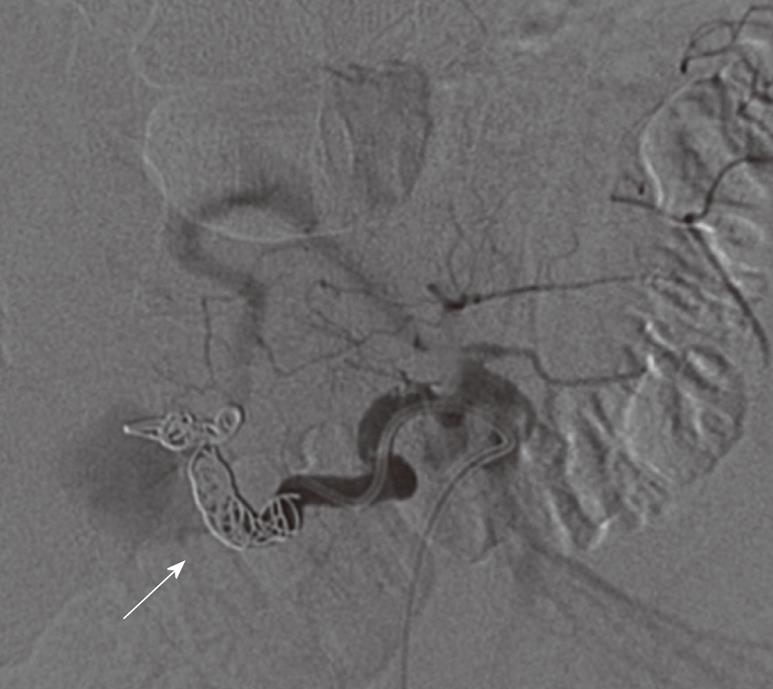

The patient underwent urgent angiographic embolization the same day with coiling of the gastroduodenal artery (Figures 3 and 4). It was successful and without any complications. A follow up bleeding scan was negative. Three days later, an abdominal CT angiogram was performed as a follow up study. There was evidence of pulmonary embolism. Intravenous contrast filled the previously described aneurysm in the region of the gastroduodenal artery, measuring 1.6 cm × 1.5 cm. There was a slight increase in size of the retroperitoneal bleed. After placing a Greenfield filter, another attempt by intervention radiology to coil the aneurysm failed. Surgical intervention was the last resort with an exploratory laparotomy and successful ligation of the aneurysm. A 1 wk follow up CT abdomen showed shrinkage of the retroperitoneal hematoma.

Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm has always been reported in the literature as rare case reports. Therefore, there is no clear evidence concerning the best time to diagnose it or a clear algorithm of how to manage it. GDA aneurysm is a rare potential life-threatening condition reported in 0.5% of all visceral aneurysms[2]. In a routine autopsy series, visceral artery aneurysms were reported in 0.01% to 0.2%[1]. In other series, GDA aneurysms account for 1.5% of all visceral aneurysms[1,3,4]. Depending on the studied population, the mean age was between 50 and 58 years[5,6]. The male/female ratio is 4.5:1 and the mean size 3.6 cm[5]. The most common identified condition associated with GDA aneurysm is chronic pancreatitis[7]. Other associated conditions are liver cirrhosis[8], other vascular abnormalities such as fibro-muscular dysplasia and poly-arteritis nodosa and predisposing events such trauma and septic emboli[9]. The pathogenesis of GDA aneurysm is not well known with trauma, hypertension and atherosclerosis as possible risk factors[10]. Abdominal pain is the main symptom which can occur with or without rupture. Other symptoms include hypotension, gastric outlet obstruction[11] and other nonspecific symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea and jaundice[12,13]. The most serious clinical scenario is upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage which occurs in about 50% of ruptured GDA aneurysms with retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal bleeds occurring less frequently[11,12,14]. In other cases, the presence of a pulsatile abdominal mass with a bruit could be the presenting warning sign[11]. The risk of rupture is high at up to 75% of cases with a mortality rate of about 20%[5]. Therefore, early diagnosis with a high level of suspicion can prevent the worst outcomes in this group of patients. Prior to the era of sophisticated imaging modalities, GDA aneurysms were diagnosed after rupture in the majority of cases. At this time, various imaging modalities are available with more cases diagnosed in asymptomatic patients.

The Gold standard diagnostic test is visceral angiography[15]. It is usually performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Plain X-ray of the abdomen is rarely helpful in suspected visceral aneurysms with shell-like calcification in an atherosclerotic aneurysm as the usual possible finding[2]. Among all diagnostic modalities, angiography is the most sensitive (100%) followed by computed tomography (67%) and ultrasonography (50%). Upper endoscopy has a sensitivity of about 20%[15].

Recently, other diagnostic modalities are available including Pulse Doppler US, color Doppler US, endoscopic ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging[16-18]. Three dimensional CT has been reported to be an accurate diagnostic especially in locating the aneurysm and its relations to adjacent vasculature[6].

It has an advantage of being less invasive and therefore more useful than angiography to diagnose the location of the aneurysm.

Therapeutic modalities depend of the type of presentation and are usually made on individual basis. Endovascular trans-catheter embolization is the most popular despite the potential risk of visceral ischemia and organs embolization[19]. In our case, this was complicated by pulmonary embolism in a patient with a ruptured GDA aneurysm. The patient required GFF placement and eventually required surgical ligation of the aneurysm. Endovascular embolization is considered the treatment of choice for hemodynamically stable patients. Surgical intervention is usually reserved for actively bleeding patients and when embolization fails[20].

In conclusion, GDA aneurysm rupture is a serious fatal manifestation of a rare condition. It requires a high level of suspicion and warning signs and symptoms warrant further investigation with computed tomography being the most useful available test. Prompt diagnosis before rupture can change the course of this condition and prevent potential lethal complications. The prognosis of GDA aneurysm is generally excellent when diagnosed before rupture and treatment is usually definitive. Giving the rarity of this condition, there are no clear screening or follow-up guidelines. Decisions about diagnostic and therapeutic procedures should be made on an individual basis.

Peer reviewer: Paolo Massucco, MD, Department of Surgical Oncology, IRCC, Str Stat 142, Candiolo 10060, Italy

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Yang C

| 1. | Røkke O, Søndenaa K, Amundsen S, Bjerke-Larssen T, Jensen D. The diagnosis and management of splanchnic artery aneurysms. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:737-743. |

| 2. | Deterling RA Jr. Aneurysm of the visceral arteries. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1971;12:309-322. |

| 3. | Carr SC, Mahvi DM, Hoch JR, Archer CW, Turnipseed WD. Visceral artery aneurysm rupture. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:806-811. |

| 4. | Shanley CJ, Shah NL, Messina LM. Uncommon splanchnic artery aneurysms: pancreaticoduodenal, gastroduodenal, superior mesenteric, inferior mesenteric, and colic. Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10:506-515. |

| 5. | Morita Y, Kawamura N, Saito H, Shinohara M, Irie G, Okushiba S, Kato H, Tanabe T, Yonekawa M, Kawamura A. [Diagnosis and embolotherapy of aneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery]. Rinsho Hoshasen. 1988;33:555-561. |

| 6. | Matsuzaki Y, Inoue T, Kuwajima K, Ito Y, Okauchi Y, Kondo H, Horiuchi N, Nakao K, Hasegawa K, Iwata M. Aneurysm of the Gastroduodenal Artery. Int Med Vol. 1998;37:930-933. |

| 7. | White AF, Baum S, Buranasiri S. Aneurysms secondary to pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:393-396. |

| 8. | Matsuno Y, Mori Y, Umeda Y, Imaizumi M, Takiya H. Surgical repair of true gastroduodenal artery aneurysm: a case report. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2008;42:497-499. |

| 9. | Tulsyan N, Kashyap VS, Greenberg RK, Sarac TP, Clair DG, Pierce G, Ouriel K. The endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:276-283; discussion 283. |

| 10. | Coll DP, Ierardi R, Kerstein MD, Yost S, Wilson A, Matsumoto T. Aneurysms of the pancreaticoduodenal arteries: a change in management. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:286-291. |

| 11. | Eckhauser FE, Stanley JC, Zelenock GB, Borlaza GS, Freier DT, Lindenauer SM. Gastroduodenal and pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms: a complication of pancreatitis causing spontaneous gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Surgery. 1980;88:335-344. |

| 12. | Moore E, Matthews MR, Minion DJ, Quick R, Schwarcz TH, Loh FK, Endean ED. Surgical management of peripancreatic arterial aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:247-253. |

| 13. | Bassaly I, Schwartz IR, Pinchuck A, Lerner R. Aneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery presenting as common duct obstruction with jaundice. Review of literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1973;59:435-440. |

| 14. | Iyomasa S, Matsuzaki Y, Hiei K, Sakaguchi H, Matsunaga H, Yamaguchi Y. Pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm: a case report and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:161-166. |

| 15. | Yeh TS, Jan YY, Jeng LB, Hwang TL, Wang CS, Chen MF. Massive extra-enteric gastrointestinal hemorrhage secondary to splanchnic artery aneurysms. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1152-1156. |

| 16. | Katsumori T, Yamane T, YokoyamaY . Ultrasonographic findings of a case of gastroduodenal and splenic artery aneurysms by B-mode, two dimensional and pulsed Doppler US. Nihon Cho-onpa Igakukaishi (JSUM Proceedings). 1990;53-54. |

| 17. | el-Dosoky MM, Reeders JW, Dol J, Bienfait HP. Radiological diagnosis of gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm in acute pancreatitis. Eur J Radiol. 1994;18:235-237. |

| 18. | Ochi T, Suzuki T, Yoshioka N, Ogawa Y, Inagaki T, Suzuki S. [A case of aneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography--review of literatures in Japan]. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;89:522-527. |

| 19. | Kasirajan K, Greenberg RK, Clair D, Ouriel K. Endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysm. J Endovasc Ther. 2001;8:150-155. |