Published online Jul 27, 2010. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i7.231

Revised: July 15, 2010

Accepted: July 22, 2010

Published online: July 27, 2010

A chronic anal fissure is a common perianal condition. This review aims to evaluate both existing and new therapies in the treatment of chronic fissures. Pharmacological therapies such as glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), Diltiazem ointment and Botulinum toxin provide a relatively non-invasive option, but with higher recurrence rates. Lateral sphincterotomy remains the gold standard for treatment. Anal dilatation has no role in treatment. New therapies include perineal support devices, Gonyautoxin injection, fissurectomy, fissurotomy, sphincterolysis, and flap procedures. Further research is required comparing these new therapies with existing established therapies. This paper recommends initial pharmacological therapy with GTN or Diltiazem ointment with Botulinum toxin as a possible second line pharmacological therapy. Perineal support may offer a new dimension in improving healing rates. Lateral sphincterotomy should be offered if pharmacological therapy fails. New therapies are not suitable as first line treatments, though they can be considered if conventional treatment fails.

- Citation: Poh A, Tan KY, Seow-Choen F. Innovations in chronic anal fissure treatment: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 2(7): 231-241

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v2/i7/231.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v2.i7.231

A chronic anal fissure is a non-healing linear tear in the distal anal mucosa below the dentate line. An anal fissure is likely to be non-healing if the fissure persists beyond 4 wk. A chronic fissure can be identified by the presence of indurated edges, visible internal sphincter fibres at the base of the fissure, a sentinel polyp at the distal end of the fissure or a fibroepithelial polyp at the apex. A chronic fissure classically occurs at the posterior midline position (6 o’clock position), with the anterior midline position occurring in 10% of females and 1% of males. Fissures occurring at positions other than the 6 o’clock position or the presence of multiple fissures may suggest other pathologies like tuberculosis, inflammatory bowel disease, syphilis and immunosuppressive diseases like Human immunodeficiency virus[1-3].

Chronic anal fissures can occur in all age groups, though it is more common in young and otherwise healthy adults. In Australia, anal fissures account for 6.2% to 15% of all visits and 10% of all operations in colorectal units[4]. In the United Kingdom, 10% of visits to colorectal units are for anal fissures[5].

There have been changes to the hypothesis of the development of anal fissures over the years. The initial hypothesis was that of anal canal trauma, most commonly by the passage of hard stools or bouts of diarrhoea[1-3]. However, this only accounted for acute fissures but not the progression to chronic non-healing anal fissures even after the bowel consistency had improved.

Subsequent studies have elucidated two additional factors that may account for the persistence of chronic anal fissures[1-3]. The first factor is the presence of persistently high basal internal sphincter tone in the majority of individuals with chronic anal fissures. A long high pressure zone in the anal canal with ultra-slow waves is seen commonly in these patients[1]. Pain is likely to be a contributing factor, though the hypertonia is unlikely to be secondary to pain alone as it persists despite the alleviation of pain with application of topical local anaesthetic[1].

The second factor is the presence of ischemia causing non-healing of the anal fissure. The distal anal canal where fissures occur is supplied by inferior rectal arteries, branches of the internal pudendal artery. These arteries traverse through the internal anal sphincter to supply the anal mucosa. Angiography of the vessels shows a relative deficiency of arterioles in the posterior commissure of the anal canal in 85% of individuals[1]. This area is usually only supplied by end vessels and is thus more susceptible to ischaemia. This is the same area where the majority of chronic anal fissures tend to occur. Laser Doppler flowmetry also demonstrate that blood flow to the distal anal canal decreases with increasing anal pressure and vice versa. As such, it has been postulated that the high anal pressure and ischaemia go hand-in-hand.

The current understanding is that there is an initiating trauma to the anal canal caused by the passage of hard stools or diarrhoea episodes. In susceptible individuals with internal sphincter hypertonia, there is little or no healing of the anal mucosa after the initial trauma. This is due to ischemia of the tissues around the anal fissure, especially the posterior commissure, by compression of the inferior rectal arteries from the internal sphincter. The paucity of blood flow prevents healing of the anal fissure until the cycle of internal sphincter hypertonia and decreased blood flow is broken by muscle relaxants or surgery.

In addition to the above two factors, it has been postulated that the pathogenesis of posterior anal fissures is contributed by the repeated preferential over-stretching of the posterior anal sphincter complex and perineum[6,7]. This is very likely secondary to the direction of the passage of faeces due to the anorectal angle. Furthermore there is a relative paucity of support between the coccyx and the anorectal ring. This preferential over-stretching of the posterior perineum need not occur with full perineal descent. In these cases, any descent is likely to be very subtle. Many of the patients with posterior anal fissures actually do not have clinical perineal descent. This syndrome in turn perpetuates the cycle of anal trauma causing pain and increased internal sphincter tone which in turn leads to mucosa ischemia and non-healing fissures. The fissure is subsequently exposed to trauma again, restarting the whole cycle.

A small subgroup of patients (about 11% of chronic anal fissure patients) develops chronic anal fissures after child delivery[1]. These fissures tend to occur in the anterior midline and are associated with difficult or instrumental deliveries. The hypothesis is that there is an initial shearing force on the anal mucosa as a result of passage of the fetal head. There is subsequent tethering of the anal mucosa to the underlying muscle which predisposes to further trauma. Significantly, these patients often do not have raised anal tone.

The principle aim of treatment for chronic anal fissures is to decrease internal sphincter tone and hence increase the blood flow with subsequent tissue healing. Treatment options include pharmacological and surgical means.

Conventional pharmacological treatment involves the use of muscle relaxants, commonly topical and occasionally oral agents. These agents include nitrates [ISDN or glyceryl trinitrate (GTN)], calcium channel blockers, Botulinum toxin, α-adrenoreceptor antagonists, β-adrenoreceptor agonists and muscarinic agonists. Newer pharmacological agents being tested include Gonyautoxin, a paralytic neurotoxin derived from shellfish[8].

Conventional surgical therapy involves finger anal dilatation and lateral internal sphincterotomy. Finger anal dilatation is generally regarded by many colorectal surgeons to be an obsolete method as finger dilatation has been associated with the development of anal incontinence. Lateral sphincterotomy has been regarded as the gold standard for treatment of chronic fissures. Newer surgical therapies that have evolved include local flap procedures such as V-Y advancement flaps and rotation flaps[9,10]. Attempts at fissure revision have lead to the development of fissurectomy and fissurotomy procedures[11,12]. New interest in the technique of anal dilatation has lead to the development of calibrated and controlled procedures with anal dilatators or pneumatic balloons[13-15]. A new method of blunt division of internal sphincter fibers termed sphincterolyis has also been attempted[16].

In evaluating the results of the various modalities of treatment, the healing, recurrence and incontinence rates are of key interest. We have collated various studies and divided them into 2 categories-comparison of the various pharmacological therapies and comparison of surgical therapies (Tables 1 to 4).

| S/N | Ref. | Study details | Healing | Remarks |

| 1 | Lund et al[17] 1997 Double armed, prospective, randomized | 0.2% GTN vs placebo 80 patients | GTN-68% healing rate within 8 wk Placebo-8% healing rate Recurrences-7.9% in GTN group. Treated successfully with additional 6 wk of GTN | |

| 2 | Kennedy et al[18] 1999 Double arm, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled | 0.2% GTN vs placebo 43 patients | GTN group-46% healing rate Placebo group-16% healing rate | Statistically significant |

| 3 | Altomare et al[19] 2000 Double arm, prospective, randomized | 0.2% GTN vs placebo 132 patients | GTN-49.2% healing rate Placebo-51.7% healing rate Recurrence-19% in GTN group | Failed to establish superiority of GTN over placebo |

| 4 | Scholefield et al[20] 2003 Four armed, prospective, randomized | 0.1% GTN vs 0.2% GTN vs 0.4% GTN vs placebo 200 patients | Intention-to-treat analysis: Placebo-37.5% healing rate 0.1% GTN-46.9% healing rate 0.2% GTN-40.4% healing rate 0.4% GTN-54.1% healing rate | High placebo healing rates noted-possibly due to inclusion of acute fissures Lowest healing rate with 0.2% GTN likely due to anomaly due to small sample size |

| 5 | Kocher et al[23] 2002 Double arm, prospective, randomized | 0.2% GTN vs 2% Diltiazem cream 61 patients | GTN-25/29 (86.2%) patients improved or healed Diltiazem-24/31 (77.4%) patients healed or improved | |

| 6 | Knight et al[27] 2001 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | 2% Diltiazem cream for chronic anal fissures 71 patients | 59/66 (89.4%) patients healed within 16 wk 7/59 (11.8%) patients on follow-up developed recurrences | |

| 7 | Carapeti et al[25] 2002 Two separate pilot studies | 2% Diltiazem cream vs 0.1% bethanechol gel 30 patients | Diltiazem-67% healing rate Bethanechol-60% healing rate | |

| 8 | Jonas et al[26] 2002 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Topical 2% Diltiazem for fissures failing GTN therapy 39 patients | 49% healing rate | |

| 9 | Maria et al[21] 1998 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Botulinum toxin 20 units vs saline 30 patients | Botulinum toxin-11/15 (73.3%) patients healed at 2 mo. Remaining 4 patients (26.7%) healed after additional 25 units Saline-2/12 patients healed at 2 mo No recurrences in the botulinum group | |

| 10 | Lindsey et al[24] 2003 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Botulinum toxin 20 units injection for non-healing anal fissures after initial 8 wk of 0.2% GTN 40 patients | 43% complete healing 12% unhealed with symptom resolution 18% unhealed with symptom improvement 27% unhealed with no symptom improvement 27% underwent eventual surgery | |

| 11 | Brisinda et al[22] 1999 Dual arm, prospective randomized, non-controlled | Botulinum toxin 20 units injection vs 0.2% GTN for 8 wk Failure to heal after 8 wk-treatment offered from the other arm 50 patients | Botulinum toxin–96% healed fissures after 2 mo 0.2% GTN-60% healed fissures after 2 mo | Statistically significant |

| 12 | Jones et al[28] 2006 Dual arm, prospective randomized, non-controlled | Botulinum toxin 25 units injection and 0.2% GTN vs Botulinum toxin 25 units alone 30 patients | Botulinum toxin and GTN-47% complete healing at 8 wk Botulinum toxin alone-27% complete healing Botulinum toxin and GTN-27% treatment failure by 6 mo Botulinum toxin alone-47% treatment failure by 6 mo | Not statistically significant Not statistically significant |

| 13 | Garrido et al[8] 2007 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Gonyautoxin 100 units injection 23 patients | 18/23 patients-healed in 7 d 3/23-healed in 12 d 2/23 patients-healed in 14 d |

In the studies under review (Tables 1 and 2), the baseline healing rates for chronic anal fissures left untreated or treated conservatively with stool softeners and lignocaine gel ranges from 8% to 51.7%, with the majority ranging from 16% to 31%[17-21].

| S/N | Ref. | Study details | Results |

| 1 | Lund et al[17] 1997 Double armed, prospective, randomized | 0.2% GTN vs placebo 80 patients | Headaches-56.4% (GTN) vs 17.9% (placebo) |

| 2 | Altomare et al[19] 2000 Double arm, prospective, randomized | 0.2% GTN vs placebo 132 patients | Headaches-33.8% (GTN) vs 7.8% (placebo) |

| 3 | Scholefield et al[20] 2003 Four armed, prospective, randomized | 0.1% GTN vs 0.2% GTN vs 0.4% GTN vs placebo 200 patients | Headaches-31% (treatment group) vs 12.5% (placebo group) Severe headaches-19.6% (0.4% GTN) vs 5.9% (0.2% GTN) vs 2% (0.1% GTN) vs 4.2% (placebo) |

| 4 | Knight et al[27] 2001 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | 2% Diltiazem cream for chronic anal fissures 71 patients | Complications: 1 (headache) and 1 (allergic dermatitis) |

| 5 | Jonas et al[26] 2002 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Topical 2% diltiazem for fissures failing GTN therapy 39 patients | Perineal itchiness-10% (no drop-out from treatment) |

| 6 | Maria et al[21] 1998 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Botulinum toxin 20 units vs saline 30 patients | No significant complications noted in the botulinum toxin group |

| 7 | Lindsey et al[24] 2003 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Botulinum toxin 20 units injection for non-healing anal fissures after initial 8 wk of 0.2% GTN 40 patients | 18% minor incontinence-resolved |

| 8 | Brisinda et al[22] 1999 Dual arm, prospective randomized, non-randomized | Botulinum toxin 20 units injection vs 0.2% GTN for 8 wk Failure to heal after 8 wk-treatment offered from the other arm 50 patients | Headaches – 20% in GTN arm No bleeding complications in Botulinum arm |

| 9 | Jones et al[28] 2006 Dual arm, prospective randomized, non-randomized | Botulinum toxin 25 units injection and 0.2% GTN vs Botulinum toxin 25 units alone 30 patients | Botulinum toxin and GTN-33% transient incontinence rate Botulinum toxin alone-13% transient incontinence rate |

| 10 | Garrido et al[8] 2007 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Gonyautoxin 100 units injection 23 patients | No flatus or fecal incontinence |

The healing rates for topical GTN ointment range from 40.4% to 68%[17-20,22]. The most common concentration tested was 0.2% GTN ointment, which is the usual dose used in treatment. The majority of the patients healed within 2 mo. However, recurrences do occur at a rate of 7.9% to 50%[17-20,22,23]. A study investigating the effect of GTN ointment concentrations on healing rates demonstrate a better healing rate with increasing concentrations (40.4% for 0.2% vs 54.1% for 0.4%)[20]. The most common complication is headache, occurring at a rate of 5.9% to 56.4%[17,19,20,24]. The incidence of headaches increased with increasing concentration of GTN[20]. Most studies do not report any significant incontinence symptoms.

The healing rates for topical Diltiazem ointment range from 67% to 89.4%[23,25,26]. The concentration tested was 2% Diltiazem ointment. One study investigating the use of Diltiazem as second line therapy in GTN-resistant fissures achieved a healing rate of 49%[26]. The recurrence rate reported in one study is 11.8%[27]. Complications include minor headaches in a small proportion and perianal itchiness in 10% of patients[26].

The healing rates for Botulinum toxin injection range from 27% to 96%[21,22,24,28,29]. The dosages used ranged from 20 to 25 units. The majority of the cases also healed within 2 mo, similar to rates for GTN ointment. No recurrence rates were reported in the studies, though one study reported 30% of patients with non-healing fissures but with symptomatic improvement[24] and another study reported healing in 26.7% of patients after treatment with an additional 25 units[21]. The incontinence rate reported in one study was 18%, with no permanent incontinence occurring[24].

The only study investigating Gonyautoxin injection achieved a healing rate of 100% within 14 d[8]. There were no incidences of incontinence. The rapid healing rate and complete resolution of anal fissures achieved indicates the need for further research into the use of Gonyautoxin.

The relatively poor healing rates (when compared with surgical therapy) achieved with pharmacological therapy prompted investigation into the usage of therapies combining different pharmacological agents. One study comparing Botulinum toxin alone with a combination of Botulinum toxin and GTN ointment showed a 47% healing rate with combination therapy and 27% with Botulinum toxin alone[28]. However, these figures are still inferior to those for lateral internal sphincterotomy.

Lateral internal sphincterotomy is the gold standard against which all treatments are compared. In the studies under review (Tables 3 and 4), the healing rates of sphincterotomy range from 92% to 100%, with the majority of the fissures healing within 2 mo[29,30-37]. A study comparing open vs closed sphincterotomy did not show any significant difference in the healing rates (95% for open vs 97% for closed) and incontinence rates[33]. The recurrence rates range from 0% to 15.4%, although the majority of studies report rates of 0% to 3.3%[29,34-37]. The most serious complication is anal incontinence, the majority of case of which are transient and not extending beyond 2 mo. The overall incontinence rates (early and late incontinence) range from 3.3% to 16%, with the incontinence rate beyond 2 mo at 3% to 7%[29-35,37]. A study comparing the extent of division of the internal anal sphincter showed that the incontinence rates were higher at 10.9% when divided up to the dentate line vs 2.2% when only divided up to the fissure apex[38].

| S/N | Ref. | Study details | Results | Remarks |

| 1 | Garcea et al[30] 2002 Single arm, retrospective, non-randomized | Conservative lateral sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissures 65 patients | 97% healing rate | 98% of patients had prior failure of healing with GTN Maximum of 5 mm of internal sphincter divided |

| 2 | Tocchi et al[31] 2004 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy for non-responders to 0.2% GTN 164 patients | 100% healing rate within 6 wk | |

| 3 | Liratzopoulos et al[32] 2006 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissures 246 patients | Overall healing rate-97.5% at 3 mo | |

| 4 | Wiley et al[33] 2004 Dual arm, prospective, randomized | Open vs closed lateral sphincterotomy 79 patients | Open technique-95% healing rates Closed technique-97% healing rates | Closed technique: Blind division of internal sphincter guided by finger Open technique: Division under direct vision |

| 5 | Jensen et al[34] 1984 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Lateral sphincterotomy vs simple anal dilatation | Sphincterotomy-100% healing rate Anal dilatation-96.4% Recurrences-3.3% (sphincterotomy) vs 28.6% (anal dilatation) | |

| 6 | Renzi et al[13] 2007 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Pneumatic balloon dilatation vs lateral sphincterotomy 53 patients | Balloon dilatation-83.3% healing rate Sphincterotomy-92% | Balloon dilated to 20 PSI and maintained for 6 min Division of half of internal sphincter |

| 7 | Richard et al[35] 2000 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Internal sphincterotomy vs 0.25% GTN 90 patients | Internal sphincterotomy-92.1% healing rate at 6 wk GTN-27.2% healing rate at 6 wk 5.5% of GTN group had an eventual sphincterotomy Recurrences-0 (sphincterotomy) vs 5/44 (11.4%) (GTN) | |

| 8 | Evans et al[36] 2001 Dual arm, prospective, randomized | 0.2% GTN vs lateral sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissures 65 patients | Sphincterotomy-97% healing rate after 8 wk GTN-60.6% healing rate after 8 wk 12/13 (92%) of patients not healed by GTN healed after sphincterotomy Recurrence-50% (GTN) vs 15.4% (sphincterotomy) 11/13 (85%) of GTN failures not compliant with treatment-7/13 (54%) (lack of effect) and 4/13 (31%) (headaches) | |

| 9 | Brown et al[37] 2007 Double arm, prospective, randomized, multi-centric | 2% GTN vs lateral internal sphincterotomy at 6 yr post-treatment 82 patients | GTN-11/27 (40.7%) patients had recurrence Sphincterotomy-no recurrence Patient satisfaction-100% (sphincterotomy) vs 56% (GTN) | 60% of GTN patients underwent subsequent sphincterotomy |

| 10 | Menteş et al[29] 2003 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Botulinum toxin 0.3 units/kg vs internal sphincterotomy 111 patients | Sphincterotomy healing rates-82% (1 mo)-98% (2 mo)-94% (6 mo)-94% ( 12 mo) Botulinum toxin healing rates-62.3% (1 mo)-73.8% (2 mo)-86.9% (6 mo, with a second injection given at end of 2nd month for non-healers)-75.4% (12 mo, with 7 patients having recurrences) | |

| 11 | Schiano di Visconte et al[14] 2009 Double arm, prospective, randomized | 0.25% GTN and anal cryothermal dilators BD vs 0.4% GTN 60 patients | Dilators and 0.25% GTN-86.6% healing rate 0.4% GTN-73.3% healing rate Recurrence after 1 year-3.3% (GTN and dilators) vs 13.3% (GTN only) | Dilators soaked for 15 min in 40 degrees water |

| 12 | Yucel et al[15] 2009 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Controlled intermittent anal dilatation (CIAD) vs lateral sphincterotomy 40 patients | Dilatation-90% healing rate at 2 mo Sphincterotomy-85% healing rate at 2 mo | Adjustable anal speculum dilated to 4.8 cm followed by relaxation for 15 times over 5 min |

| 13 | Singh et al[9] 2005 Single arm, prospective, non-randomised | Rotational flap for treatment of chronic anal fissures 21 patients | Complete healing in 17/21 (81.0%) patients | |

| 14 | Giordano et al[10] 2009 Single arm, prospective, non-randomised | Cutaneous advancement flap anoplasty for chronic anal fissures 51 patients | 98% healing rate No recurrences at median 6 mo follow-up 3/51 developed new fissures at new locations | |

| 15 | Pelta et al[11] 2007 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Subcutaneous fissurotomy for chronic anal fissures 109 patients | 98.2% healing rate | Opening up of subcutaneous tract beneath fissure and excision of sentinel tag |

| 16 | Soll et al[12] 2004 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Fissurectomy and botulinum toxin 20-25 units for chronic anal fissures not responsive to medical therapy 31 patients | 93% healing rate by 16 wk with 7% having symptomatic relief despite non-healing fissures | |

| 17 | Gupta[16] 2008 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Closed anal sphincter manipulation (sphincterolysis) for chronic anal fissures 312 patients | 96.5% healing rate within 8 wk No recurrence | Finger fracture of internal sphincter fibres over left lateral side without breaching anal mucosa |

| 18 | Tan et al[7] 2009 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Effect of posterior perineal support on chronic anal fissure healing | Moderate (or more) improvement in: Pain-50% (2 wk) and 97.5% (3 mo) Bleeding-46.9% (2 wk) and 65.6% (3 mo) Constipation-40.6% (2 wk) and 84.4% (3 mo) Need for laxatives-15.6% (2 wk) and 40.6% (3 mo) Abdominal discomfort-31.3% (2 wk) and 68.8% (3 mo) Decrease in pain score from 5 (before treatment) to 0 (after 3 mo) |

| S/N | Ref. | Study details | Results |

| 1 | Garcea et al[30] 2002 Single arm, retrospective, non-randomized | Conservative lateral sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissures 65 patients | Flatus or fecal incontinence-3.3% |

| 2 | Tocchi et al[31] 2004 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy for non-responders to 0.2% GTN 164 patients | Early gas and fecal soilage-9.1% Some degree of incontinence at 3 mo-3% (3/5 patients had pre-op external sphincter damage) |

| 3 | Liratzopoulos et al[32] 2006 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissures 246 patients | Incidence of new continence at 48 wk-7.02% |

| 4 | Wiley et al[33] 2004 Dual arm, prospective, randomized | Open vs closed lateral sphincterotomy 79 patients | Overall incontinence rate-6.8% (no significant difference between the 2 techniques) |

| 5 | Elsebae et al[38] 2007 Dual arm, prospective, randomized | Impact of the extent of division of internal anal sphincter on fecal incontinence 108 patients | Up till dentate line-10.86% incontinence rate Up till apex of fissure-2.17% incontinence rate |

| 6 | Jensen et al[34] 1984 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Lateral sphincterotomy vs simple anal dilatation | Flatus incontinence-0% (sphincterotomy) vs 28.6% (anal dilatation) Fecal incontinence-0% (sphincterotomy) vs 7.1% (anal dilatation) Fecal soiling of underwear-3.3% (sphincterotomy) vs 39.3% (anal dilatation) All above results statistically significant |

| 7 | Renzi et al[13] 2007 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Pneumatic balloon dilatation vs lateral sphincterotomy 53 patients | Fecal incontinence-0% (balloon dilatation) vs 16% (sphincterotomy) |

| 8 | Richard et al[35] 2000 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Internal sphincterotomy vs 0.25% GTN 90 patients | Headaches-84% (GTN) No incontinence complications Patient satisfaction-97% (sphincterotomy) vs 61% (GTN) |

| 9 | Evans et al[36] 2001 Dual arm, prospective, randomized | 0.2% GTN vs lateral sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissures 65 patients | GTN-31% headaches No mention of sphincterotomy complications |

| 10 | Brown et al[37] 2007 Double arm, prospective, randomized, multi-centric | 2% GTN vs lateral internal sphincterotomy at 6 years post-treatment 82 patients | No difference in fecal incontinence scoring between both groups No difference in symptoms of incontinence-16/24 (66.7%) (sphincterotomy) vs 18/27 (66.7%) (GTN) |

| 11 | Menteş et al[29] 2003 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Botulinum toxin 0.3 units/kg vs internal sphincterotomy 111 patients | Incontinence-8/50 (16%) patients (sphincterotomy) had transient flatus incontinence vs 0 (botulinum toxin) |

| 12 | Schiano di Visconte et al[14] 2009 Double arm, prospective, randomized | 0.25% GTN and anal cryothermal dilators BD vs 0.4% GTN 60 patients | No incontinence reported |

| 13 | Yucel et al[15] 2009 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Controlled intermittent anal dilatation (CIAD) vs lateral sphincterotomy 40 patients | No incontinence reported |

| 14 | Singh et al[9] 2005 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Rotational flap for treatment of chronic anal fissures 21 patients | 11.8% flap uptake failure with wound dehiscence No donor site complications No new incontinence complications post-op |

| 15 | Giordano et al[10] 2009 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Cutaneous advancement flap anoplasty for chronic anal fissures 51 patients | Suture line dehiscence-5.9% No incontinence complications |

| 16 | Pelta et al[11] 2007 Double arm, prospective, randomized | Subcutaneous fissurotomy for chronic anal fissures 109 patients | No incontinence complications |

| 17 | Soll et al[12] 2004 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Fissurectomy and botulinum toxin 20-25 units for chronic anal fissures not responsive to medical therapy 31 patients | 7% flatus incontinence rate lasting maximum of 6 wk |

| 18 | Gupta[16] 2008 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Closed anal sphincter manipulation (sphincterolysis) for chronic anal fissures 312 patients | 11/312 patients had incontinence symptoms within first 4 wk Complete continence restored in 97% of patients after 1 mo |

| 19 | Tan et al[7] 2009 Single arm, prospective, non-randomized | Effect of posterior perineal support on chronic anal fissure healing | No complications noted |

A study comparing internal sphincterotomy with Botulinum toxin showed a high healing rate that is sustained over a 1 year period with sphincterotomy[29]. Sphincterotomy achieved a 82% healing rate within the first month and further improvement to 94% at 12 mo. In contrast, Botulinum toxin achieved a 62.3% healing rate within the first month, reaching a peak of 86.9% at 6 mo before decreasing to 75.4% at 12 mo due to recurrences. Sixteen percent of sphincterotomy patients had flatus incontinence, though all instances were temporary in nature.

Studies comparing internal sphincterotomy with GTN ointment produced similar results to those on Botulinum toxin. The general trend was to higher healing rates, lower recurrence rates and better patient satisfaction for internal sphincterotomy. The first study[36] achieved a 60.6% healing rate and 50% recurrence rate with GTN, in contrast to sphincterotomy which achieved a 97% healing rate and 15.4% recurrence rate. In addition, 92% of GTN-failure patients achieved healing after sphincterotomy. The second study[35] achieved a 92.1% healing rate and 0% recurrence rate with no fecal incontinence with sphincterotomy, while GTN achieved a 27.2% healing rate with an 11.4% recurrence rate. Ninety-seven percent of the sphincterotomy patients were satisfied with their treatment, in contrast to 61% for GTN patients. A third study[37] showed a 40.7% recurrence rate with GTN and 0% for sphincterotomy with no difference in fecal incontinence scoring between the 2 groups. 100% of sphincterotomy patients were satisfied with their treatment, in contrast to 56% for GTN patients.

A single study reported on a new technique of division of the internal sphincter, termed sphincterolysis[16]. This technique involved the use of firm finger pressure over the internal sphincter fibres to produce a full thickness division of the fibres without breaching the anal mucosa. This study achieved healing rates of 96.5% with a 3.5% temporary incontinence rate that resolved in 97% of the affected patients within 1 mo. There were no recurrences reported. However, the technique described is rather uncontrolled and there is concern about the development of serious incontinence if it is carried out by inexperienced hands.

Digital anal dilatation is a technique which preceded lateral internal sphincterotomy. However, the unacceptably high rates of anal incontinence have rendered it obsolete. The healing rates of anal dilatation are on par with sphincterotomy, with one study comparing sphincterotomy with anal dilatation reporting healing rates of 96.4%[34]. However, the same study reported incontinence to flatus at 28.6% and feces at 7.1% for anal dilatation. In addition, the recurrence rate reported for anal dilatation was 28.6%, which is much higher than that for sphincterotomy.

There has been renewed interest in the technique of anal dilatation, although the current technique requires standardised dilatation to avoid excessive internal sphincter trauma. One study used cryothermal anal dilators heated to 40°C to perform anal dilatation in combination with GTN ointment application and achieved an 86.6% healing rate with a 3.3% incontinence rate[14]. These figures are comparable with that of sphincterotomy. In contrast, in the same study GTN ointment alone achieved a 73.3% healing rate with a 13.3% recurrence rate. A second study[15] used intermittent anal dilatation with an adjustable anal dilator and achieved a 90% healing rate with no incontinence symptoms. A further study[13] compared pneumatic balloon anal dilatation with lateral sphincterotomy and achieved comparable healing rates (83.3% for balloon dilatation vs 92% for sphincterotomy) but lower incontinence rates (0% for balloon dilatation vs 16% for sphincterotomy) for balloon dilatation.

Flap anoplasty procedures are also used in the treatment of chronic anal fissures. These procedures involve fashioning a local flap to cover the fissure defect. As flap procedures do not involve disruption of the internal anal sphincter, they are particularly useful in patients with normal anal pressures or in fissures secondary to obstetric trauma where there is often associated internal sphincter disruption. A study using a rotation flap achieved 81% healing rate with an 11.8% flap failure rate and 0% incontinence rate[9]. A second study using a V-Y advancement flap achieved a 98% healing rate with a flap dehiscence rate of 5.9% and 0% incontinence rate, but with a recurrence rate of 5.9% of new fissures at new locations[10].

Newer therapies in chronic anal fissure management include anal fissurectomy or fissurotomy. Fissurectomy involves freshening of the anal fissure to allow healing, and this includes excision of the fissure edges, curetting or excision of the fissure base and possibly excision of sentinel skin tags and anal polyps. One study investigated the role of fissurectomy in combination with Botulinum toxin injection, and achieved a 93% healing rate within 16 wk and a temporary flatus incontinence rate of 7% that resolved within 6 wk[12]. The technique of fissurotomy stems from the discovery of a subcutaneous tract underlying a chronic anal fissure, akin to an anal fistula. The laying open of this tract allows healing of the tract and also release of the perianal skin as well as widening of the anal canal, rendering internal sphincterotomy unnecessary. One study investigating subcutaneous fissurotomy reported a 98.2% healing rate with no incontinence symptoms[11]. Both of these techniques are only recently reported, and the number of studies few is number.

In addition to reduction of internal sphincter tone in treating chronic anal fissures, there is also research into the reduction of trauma during defecation. One recent study looked into the use of a posterior perineal support device incorporated into a toilet seat to improve the healing rates of chronic anal fissures[7]. This posterior perineal support device is likely to reverse the preferential over-stretching of the posterior anal sphincter complex and mucosa and thus facilitate defaecation with less trauma. This study on 32 patients with symptomatic chronic anal fissures reported: at least moderate (or greater) improvement in pain for 50% of patients at 2 wk with 97.5% improvement at 3 mo; 46.9% improvement in bleeding at 2 wk and 65.6% at 3 mo; 40.6% improvement in constipation at 2 wk and 84.4% at 3 mo; 15.6% improvement in usage of laxatives at 2 wk and 40.6% at 3 mo; 31.3% improvement in abdominal discomfort at 2 wk and 68.8% at 3 mo. The improvement in pain, bleeding, constipation and abdominal discomfort were statistically significant. The improvement in pain was also manifested in a decrease in pain score from five (before treatment) to zero (at 3 mo).

In another recent pilot study reported on reduction on pain post lateral sphincterotomy[39], methylene blue dye was injected into the perianal skin and inter-sphincteric space just before sphincterotomy was carried out. The median pain score of the patients decreased from 2.5 on post-operative day one to zero on day five. Nine out of 24 patients had no pain at all post-operatively. The improvement in pain in turn helped in fissure healing.

The data available from the various studies investigating chronic anal fissures are very heterogeneous, with a large variation in the healing rates for the same modality and also a large degree of overlap between the healing rates achieved for the different modalities. This heterogeneity can be attributed to the inclusion of acute fissures, the inclusion of patients who had already undergone previous treatment modalities and hence likely to have recalcitrant non-healing fissures and the differences between the various studies in determining the endpoint of fissure healing. In addition, many studies have allowed the addition of further treatment modalities to the primary treatment in the event of treatment failure, thus making comparison between the various studies difficult. The results of long- term follow up are also incomplete due to poor follow-up rates and the frequency of patients seeking alternative treatment in the follow-up period.

No single conventional pharmacological therapy has consistently proven to be superior to others as is evident from the results above. This can be attributed partly to the data heterogeneity mentioned above. Conventional therapies include GTN ointment, Diltiazem ointment and Botulinum toxin injections. The healing rates achieved with the various modalities are similar, with Botulinum toxin studies reporting rates of 27%[28], 43%[24], 73%[29] and 96%[22], Diltiazem studies reporting rates of 47%[26], 67%[25], 77%[23] and 89%[27] and GTN studies reporting rates of 40.4%[20], 46%[18], 49%[19], 68%[17] and 86%[23]. The incontinence rates between are also similar between studies and are generally low and the effects are reversible.

GTN ointment and Diltiazem ointment have similar healing rates (figures as mentioned above), although one study has reported additional healing of GTN-resistant fissures when treated with Diltiazem[23]. However, Diltiazem has a superior side effect profile to GTN, with an incidence of mild headaches and pruritus ani with Diltiazem use lower than that of headaches with GTN use (Table 2). In addition, the headaches reported with GTN usage tend to be more severe than those from Diltiazem usage. Both GTN and Diltiazem ointment have the advantage of being topical treatments with similar healing rates, and hence it is reasonable to consider initiating treatment with either. In the event of unacceptable side effects with GTN therapy, it is still reasonable to switch to Diltiazem therapy for a period of 4 to 6 wk before declaring treatment failure. In addition, it is reasonable to consider a trial of either therapy in the event of treatment failure of one.

Botulinum toxin injections demonstrate similar healing rates to GTN and Diltiazem (figures as mentioned above), though one study again demonstrated additional healing of GTN-resistant fissures when treated with Botulinum[24]. However, Botulinum has the disadvantage of being an invasive procedure necessitating injections in the peri-anal area, with the potential for more severe side effects such as bleeding, hematoma formation and abscess formation[1,3,21,22,24,28,40]. In addition, Botulinum toxin has the additional side effect of temporary anal incontinence that is rarely reported with GTN or Diltiazem use[24]. Botulinum toxin injections can be used as first line therapy, although because of the potentially serious side effects, it is more commonly used as second line therapy in the event of failure of GTN and/or Diltiazem therapy.

A common disadvantage in conventional pharmacological therapies (GTN, Diltiazem or Botulinum toxin) is the non-permanent effect of sphincter relaxation, resulting in a high recurrence rate of between 10% to 50% on long term follow-up[8,14,17-29,35-37].

Gonyautoxin is the newest pharmacological therapy to emerge and the initial results are optimistic with 100% healing rate within 2 wk and no incontinence reported. The mechanism of action of Gonyautoxin is the dose-dependent reversible binding of the toxin to voltage-gated sodium channels on excitable cells, thereby producing a neuronal transmission blockage. This mechanism is similar to that for Botulinum toxin in that the effects are reversible and non-permanent and so this does not solve the fundamental problem of recurrence noted in Botulinum toxin injection. However, Gonyautoxin may act in additional ways as yet undiscovered that aid fissure healing. Long term follow-up is therefore needed to determine the recurrence rate and large scale randomized placebo-controlled trials are needed to confirm the time to healing and healing rates.

The gold standard for surgical and pharmacological treatment of anal fissures is lateral internal sphincterotomy. The primary concern regarding sphincterotomy is the anal incontinence rate, which has been reported in some studies to be as high as 30%. However, the review conducted here has shown that the rate of any long term incontinence (beyond 2 mo) to be only in the range of 3.3% to 7%[16,29-37]. In addition, lateral sphincterotomy has consistently provided better healing rates, decreased recurrence rates and better patient satisfaction than pharmacological therapies. Therefore, despite the small but definite risk of permanent incontinence with sphincterotomy, sphincterotomy is still an option, alongside pharmacological therapies as first line treatment for chronic anal fissures.

The technique of sphincterolysis appears to offer an alternative to lateral internal sphincterotomy avoiding the skin incision and offering lower anal incontinence rates. However, it is questionable whether such uncontrolled manipulation of the internal sphincter will lead to less incontinence. Furthermore, the long term recurrence rate needs to be determined. As such, further investigation is still needed of this technique as there has only been a single study thus far.

The role of flap anoplasty procedures in the treatment of chronic anal fissures with raised anal pressures has not been clearly defined. There is a general consensus that sphincterotomes should be performed with some caution for chronic anal fissures in females, and should be avoided in normal anal pressure chronic anal fissures and fissures secondary to obstetric trauma. It is in these clinical circumstances that flap anoplasty procedures have a defined role in treatment. In the treatment of raised anal pressure chronic anal fissures, flap anoplasty procedures have achieved good healing rates (81% to 98%)[9,10],approaching those of lateral sphincterotomy, with minimal anal incontinence complications. Flap failure rates are however relatively high (5.9% to 11.8%) and coupled with the fact that not many studies have been conducted to clearly define the role of flap anoplasty procedures in raised anal pressure fissures, the flap anoplasty procedure is not one of the recommended first line treatments at this juncture.

Both fissurectomy and fissurotomy are recently developed surgical techniques. Fissurotomy alone and the combination of fissurectomy with Botulinum toxin and have achieved similar healing rates to sphincterotomy. However, the lack of studies and long term follow-up have hampered reporting of complication and recurrence rates.

Simple finger anal dilatation has no role in the modern day treatment of chronic anal fissures due to the unacceptably high anal incontinence rates. The new techniques of anal dilatation utilize controlled dilatation with calibrated equipment to ensure consistency and avoid excessive tearing of the internal anal sphincter with associated incontinence. These new techniques have achieved similar healing rates to sphincterotomy with a much lower incontinence rate compared to conventional finger anal dilatation. It is important to note that these studies only have small study populations (60[14], 40[15] and 53[13] patients respectively), and larger scale randomized placebo-controlled studies are needed to verify the data. The recurrence rates have not been verified by long-term follow-up, and this aspect will also need further investigation.

The recent study describing the usage of a posterior perineal support device[7] to decrease recurrent trauma to anal mucosa represents another approach to chronic anal fissure management other than reduction of internal sphincter tone. It has the advantage of being a non-invasive technique. The posterior perineal support device is purported to help support and hold up the anococcygeal region just posterior to the posterior anal wall, hence providing pressure to the posterior aspect of the pelvic floor to counteract the pressure exerted by the feces. This confers two advantages, the first is the enhancement of the defecation reflex for effective defecation and decreased straining and the second is the reduction in tissue stretching and tension of the posterior perineum and levator ani muscles. The initial results show promise, with over 75% of patients expressing moderate or greater improvement in two or more symptoms associated with chronic anal fissures as well as a decrease in pain score from five to zero. This device may be used as an adjuvant to pharmacological therapies.

The role of ancillary methods to further improve wound healing and reduce post-operative pain has been described. The first study which described improved wound healing after hemorrhoidectomy with GTN ointment[41] has applications in the wound healing rates in flap anoplasty, fissurectomy and fissurotomy. GTN decreases anal sphincter tone and improves blood flow, with benefits on tissue healing and may potentially help in improving flap uptake rates. The same study also indicated that GTN may have an effect in decreasing pain through decrease in anal sphincter spasm (though no improvement of pain

score was noted in this study). This effect of GTN has not been confirmed due to conflicting reports from other studies[42-44]. A second study reported decrease in post-operative pain after lateral sphincterotomy with peri-anal and inter-sphincteric methylene blue injections[39]. The proposed mechanism was the destruction of dermal nerve endings[45]. Pain improvement allows the patient to have regular bowel movement, preventing formation of hard stools and constipation and hence anal mucosa trauma. Both of these studies are limited by small patient numbers, and the results need to be validated by large scale studies. However, these findings may have wide ranging implications in anorectal surgery.

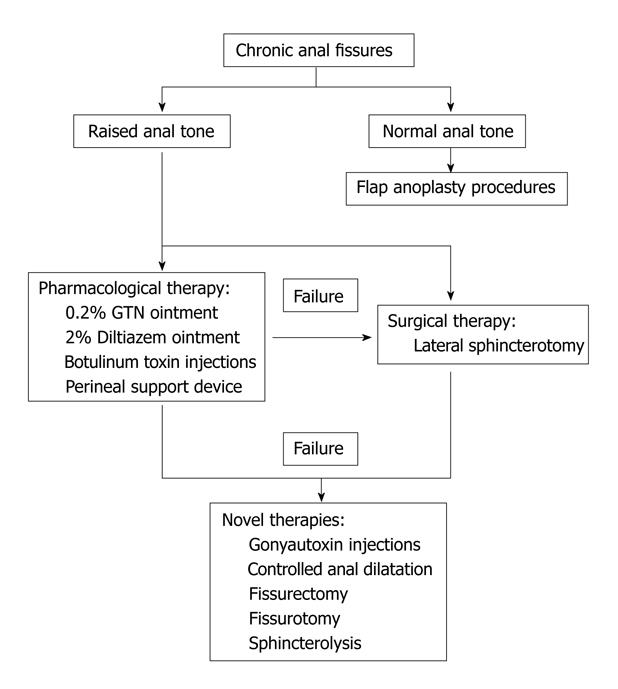

The recommended treatment algorithm was shown in Figure 1.

Pharmacological therapies such as 0.2% GTN, 2% Diltiazem ointment or Botulinum toxin injection can be tried as initial treatment for chronic anal fissures. The perineal support device provides an interesting and non-invasive approach to treating chronic fissures by decreasing anal mucosa trauma and can be an adjuvant to pharmacological therapies. A larger scale randomized controlled trial is being performed currently. Where there is failure of either GTN or Diltiazem treatment, it is reasonable to offer Botulinum injections as second line pharmacological treatment if the patient is still positive to pharmacological options. Lateral internal sphincterotomy can be offered as primary treatment in patients who do not wish to try pharmacological therapy.

In cases of failure of all pharmacological therapy options or discontinuation due to complications, lateral internal sphincterotomy should be offered. Division of the internal sphincter up to the apex of the fissure will help minimize anal incontinence.

Flap anoplasty procedures should be offered for normal anal pressure anal fissures and fissures secondary to obstetric trauma. The role of flap anoplasty as primary treatment in high pressure anal fissures is not as established as lateral internal sphincterotomy, but can be considered if the patient does not favour sphincterotomy.

Novel therapies such as Gonyautoxin injection, controlled anal dilatation, sphincterolysis, fissurectomy and fissurotomy are not well established treatments and will need further research before their roles in the treatment of chronic anal fissures can be determined. In the event of failure of both pharmacological therapy and lateral sphincterotomy, these novel therapies can be attempted.

The use of ancillary methods like GTN ointment and methylene blue injections to improve wound healing and post-operative pain can potentially accelerate healing for all anal fissure procedures and has wide-ranging implications on anorectal surgery.

Peer reviewer: Giulio A Santoro, Professor, Pelvic Floor Unit and Colorectal Unit, Department of Surgery, Regional Hospital, Treviso 31000, Italy

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Yang C

| 1. | Jonas M, Scholefield JH. Anal Fissure. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:167-181. |

| 2. | Van Outryve M. Physiopathology of the anal fissure. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106:517-518. |

| 3. | Utzig MJ, Kroesen AJ, Buhr HJ. Concepts in pathogenesis and treatment of chronic anal fissure--a review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:968-974. |

| 4. | Lubowski DZ. Anal fissures. Aust Fam Physician. 2000;29:839-844. |

| 5. | Garner JP, McFall M, Edwards DP. The medical and surgical management of chronic anal fissure. J R Army Med Corps. 2002;148:230-235. |

| 6. | Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59:477-482. |

| 7. | Tan KY, Seow-Choen F, Hai CH, Thye GK. Posterior perineal support as treatment for anal fissures--preliminary results with a new toilet seat device. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:11-15. |

| 8. | Garrido R, Lagos N, Lattes K, Abedrapo M, Bocic G, Cuneo A, Chiong H, Jensen C, Azolas R, Henriquez A. Gonyautoxin: new treatment for healing acute and chronic anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:335-340; discussion 340-343. |

| 9. | Singh M, Sharma A, Gardiner A, Duthie GS. Early results of a rotational flap to treat chronic anal fissures. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:339-342. |

| 10. | Giordano P, Gravante G, Grondona P, Ruggiero B, Porrett T, Lunniss PJ. Simple cutaneous advancement flap anoplasty for resistant chronic anal fissure: a prospective study. World J Surg. 2009;33:1058-1063. |

| 11. | Pelta AE, Davis KG, Armstrong DN. Subcutaneous fissurotomy: a novel procedure for chronic fissure-in-ano. a review of 109 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1662-1667. |

| 12. | Soll C, Dindo D, Hahnloser D. Combined fissurectomy and botulinum toxin injection. A new therapeutic approach for chronic anal fissures. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:667-670. |

| 13. | Renzi A, Izzo D, Di Sarno G, Talento P, Torelli F, Izzo G, Di Martino N. Clinical, manometric, and ultrasonographic results of pneumatic balloon dilatation vs. lateral internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:121-127. |

| 14. | Schiano di Visconte M, Munegato G. Glyceryl trinitrate ointment (0.25%) and anal cryothermal dilators in the treatment of chronic anal fissures. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1283-1291. |

| 15. | Yucel T, Gonullu D, Oncu M, Koksoy FN, Ozkan SG, Aycan O. Comparison of controlled-intermittent anal dilatation and lateral internal sphincterotomy in the treatment of chronic anal fissures: a prospective, randomized study. Int J Surg. 2009;7:228-231. |

| 16. | Gupta PJ. Closed anal sphincter manipulation technique for chronic anal fissure. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2008;73:29-32. |

| 17. | Lund JN, Scholefield JH. A randomised, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of glyceryl trinitrate ointment in treatment of anal fissure. Lancet. 1997;349:11-14. |

| 18. | Kennedy ML, Sowter S, Nguyen H, Lubowski DZ. Glyceryl trinitrate ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of a placebo-controlled trial and long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1000-1006. |

| 19. | Altomare DF, Rinaldi M, Milito G, Arcanà F, Spinelli F, Nardelli N, Scardigno D, Pulvirenti-D'Urso A, Bottini C, Pescatori M. Glyceryl trinitrate for chronic anal fissure--healing or headache? Results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controled, double-blind trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:174-179; discussion 179-181. |

| 20. | Scholefield JH, Bock JU, Marla B, Richter HJ, Athanasiadis S, Pröls M, Herold A. A dose finding study with 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.4% glyceryl trinitrate ointment in patients with chronic anal fissures. Gut. 2003;52:264-269. |

| 21. | Maria G, Cassetta E, Gui D, Brisinda G, Bentivoglio AR, Albanese A. A comparison of botulinum toxin and saline for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:217-220. |

| 22. | Brisinda G, Maria G, Bentivoglio AR, Cassetta E, Gui D, Albanese A. A comparison of injections of botulinum toxin and topical nitroglycerin ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:65-69. |

| 23. | Kocher HM, Steward M, Leather AJ, Cullen PT. Randomized clinical trial assessing the side-effects of glyceryl trinitrate and diltiazem hydrochloride in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg. 2002;89:413-417. |

| 24. | Lindsey I, Jones OM, Cunningham C, George BD, Mortensen NJ. Botulinum toxin as second-line therapy for chronic anal fissure failing 0.2 percent glyceryl trinitrate. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:361-366. |

| 25. | Carapeti EA, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Topical diltiazem and bethanechol decrease anal sphincter pressure and heal anal fissures without side effects. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1359-1362. |

| 26. | Jonas M, Speake W, Scholefield JH. Diltiazem heals glyceryl trinitrate-resistant chronic anal fissures: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1091-1095. |

| 27. | Knight JS, Birks M, Farouk R. Topical diltiazem ointment in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg. 2001;88:553-556. |

| 28. | Jones OM, Ramalingam T, Merrie A, Cunningham C, George BD, Mortensen NJ, Lindsey I. Randomized clinical trial of botulinum toxin plus glyceryl trinitrate vs. botulinum toxin alone for medically resistant chronic anal fissure: overall poor healing rates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1574-1580. |

| 29. | Menteş BB, Irkörücü O, Akin M, Leventoğlu S, Tatlicioğlu E. Comparison of botulinum toxin injection and lateral internal sphincterotomy for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:232-237. |

| 30. | Garcea G, Sutton C, Mansoori S, Lloyd T, Thomas M. Results following conservative lateral sphincteromy for the treatment of chronic anal fissures. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:311-314. |

| 31. | Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Miccini M, Cassini D, Bettelli E, Brozzetti S. Total lateral sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:245-249. |

| 32. | Liratzopoulos N, Efremidou EI, Papageorgiou MS, Kouklakis G, Moschos J, Manolas KJ, Minopoulos GJ. Lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy in the treatment of chronic anal fissure: our experience. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:143-147. |

| 33. | Wiley M, Day P, Rieger N, Stephens J, Moore J. Open vs. closed lateral internal sphincterotomy for idiopathic fissure-in-ano: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:847-852. |

| 34. | Jensen SL, Lund F, Nielsen OV, Tange G. Lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy versus anal dilatation in the treatment of fissure in ano in outpatients: a prospective randomised study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289:528-530. |

| 35. | Richard CS, Gregoire R, Plewes EA, Silverman R, Burul C, Buie D, Reznick R, Ross T, Burnstein M, O'Connor BI. Internal sphincterotomy is superior to topical nitroglycerin in the treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of a randomized, controlled trial by the Canadian Colorectal Surgical Trials Group. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1048-1057; discussion 1057-1058. |

| 36. | Evans J, Luck A, Hewett P. Glyceryl trinitrate vs. lateral sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:93-97. |

| 37. | Brown CJ, Dubreuil D, Santoro L, Liu M, O'Connor BI, McLeod RS. Lateral internal sphincterotomy is superior to topical nitroglycerin for healing chronic anal fissure and does not compromise long-term fecal continence: six-year follow-up of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:442-448. |

| 38. | Elsebae MM. A study of fecal incontinence in patients with chronic anal fissure: prospective, randomized, controlled trial of the extent of internal anal sphincter division during lateral sphincterotomy. World J Surg. 2007;31:2052-2057. |

| 39. | Tan KY, Seow-Choen F. Methylene blue injection reduces pain after lateral anal sphincterotomy. Tech Coloproctol. 2007;11:68-69. |

| 40. | Collins EE, Lund JN. A review of chronic anal fissure management. Tech Coloproctol. 2007;11:209-223. |

| 41. | Tan KY, Sng KK, Tay KH, Lai JH, Eu KW. Randomized clinical trial of 0.2 per cent glyceryl trinitrate ointment for wound healing and pain reduction after open diathermy haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1464-1468. |

| 42. | Elton C, Sen P, Montgomery AC. Initial study to assess the effects of topical glyceryl trinitrate for pain after haemorrhoidectomy. Int J Surg Investig. 2001;2:353-357. |

| 43. | Wasvary HJ, Hain J, Mosed-Vogel M, Bendick P, Barkel DC, Klein SN. Randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of effect of nitroglycerin ointment on pain after hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1069-1073. |

| 44. | Hwang DY, Yoon SG, Kim HS, Lee JK, Kim KY. Effect of 0.2 percent glyceryl trinitrate ointment on wound healing after a hemorrhoidectomy: results of a randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:950-954. |

| 45. | Eusebio EB, Graham J, Mody N. Treatment of intractable pruritus ani. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:770-772. |