Published online Dec 27, 2010. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i12.405

Revised: September 19, 2010

Accepted: September 26, 2010

Published online: December 27, 2010

Since actinomycosis sometimes causes an abdominal tumor which mimics malignancy, treatment strategy varies from case to case. We herein report two cases which were treated with a combination of antibiotics and surgical intervention. Both patients presented with an intra-abdominal tumor lesion mimicking malignant disease after an appendectomy for acute appendicitis. Case 1 received surgical extirpation of the abdominal tumor in the liver and kidney twice since the clinical diagnosis of actinomycosis was not made. In contrast, case 2 was successfully treated by a combination of antibiotics and laparoscopic surgery following the experience of case 1. When a high probability diagnosis can be made, a laparoscopic approach is a useful and effective option to treat this condition.

- Citation: Hayashi M, Asakuma M, Tsunemi S, Inoue Y, Shimizu T, Komeda K, Hirokawa F, Takeshita A, Egashira Y, Tanigawa N. Surgical treatment for abdominal actinomycosis: A report of two cases. World J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 2(12): 405-408

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v2/i12/405.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v2.i12.405

Actinomycosis is a chronic suppurative granulomatous inflammation caused by the Actinomyces species, a microaerophilic, anaerobic Gram-positive rod[1]. The disease process includes an autologous infection mainly induced by surgery. The abdomen is the most frequent site for actinomycosis and when an abdominal tumor presents as the clinical symptom, the local lesion needs to be differentiated from abdominal tumors of other etiologies, malignancy in particular. Preoperative diagnosis is usually difficult with the majority of cases being diagnosed after the histological and bacteriological examination of the resected specimen[2-5].

We herein report on two cases which were treated with a combination of antibiotics and surgical intervention. When actinomycosis is already presumed with a high probability as the clinical diagnosis beforehand, a laparoscopic approach is a useful option to treat this entity, providing beneficial effect for patients quality of life.

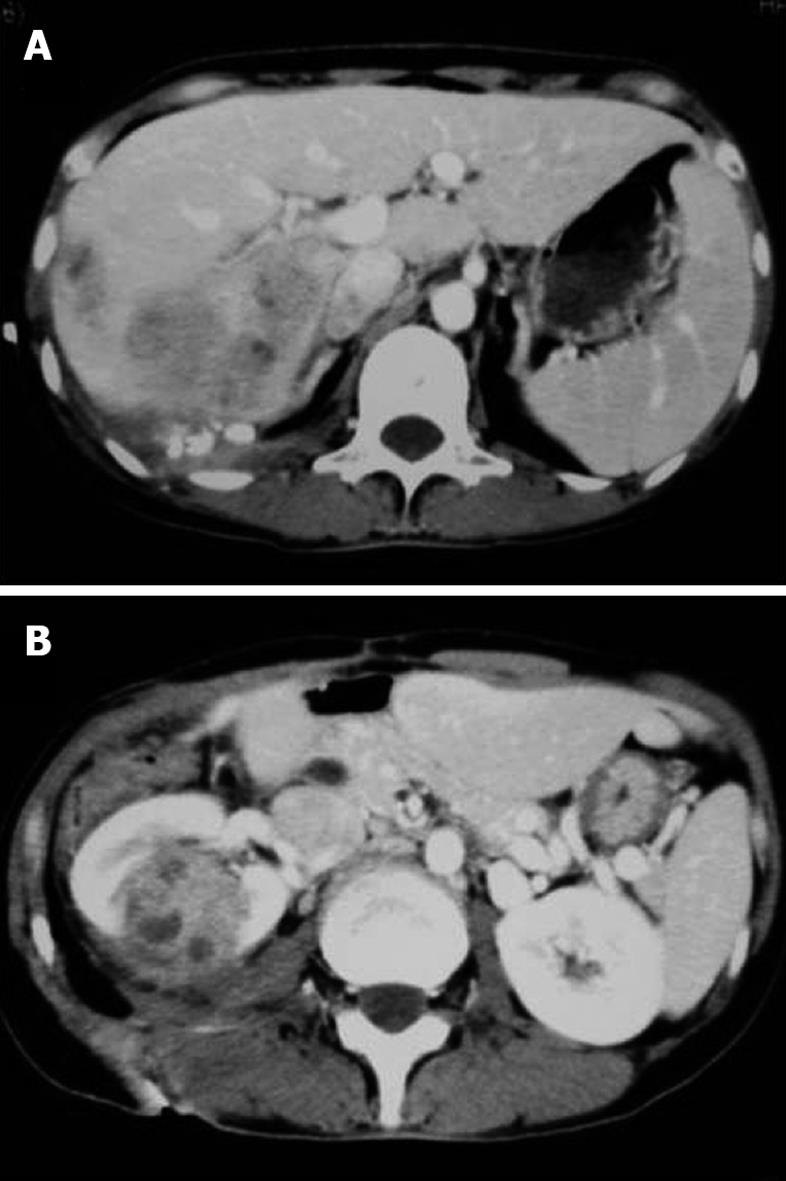

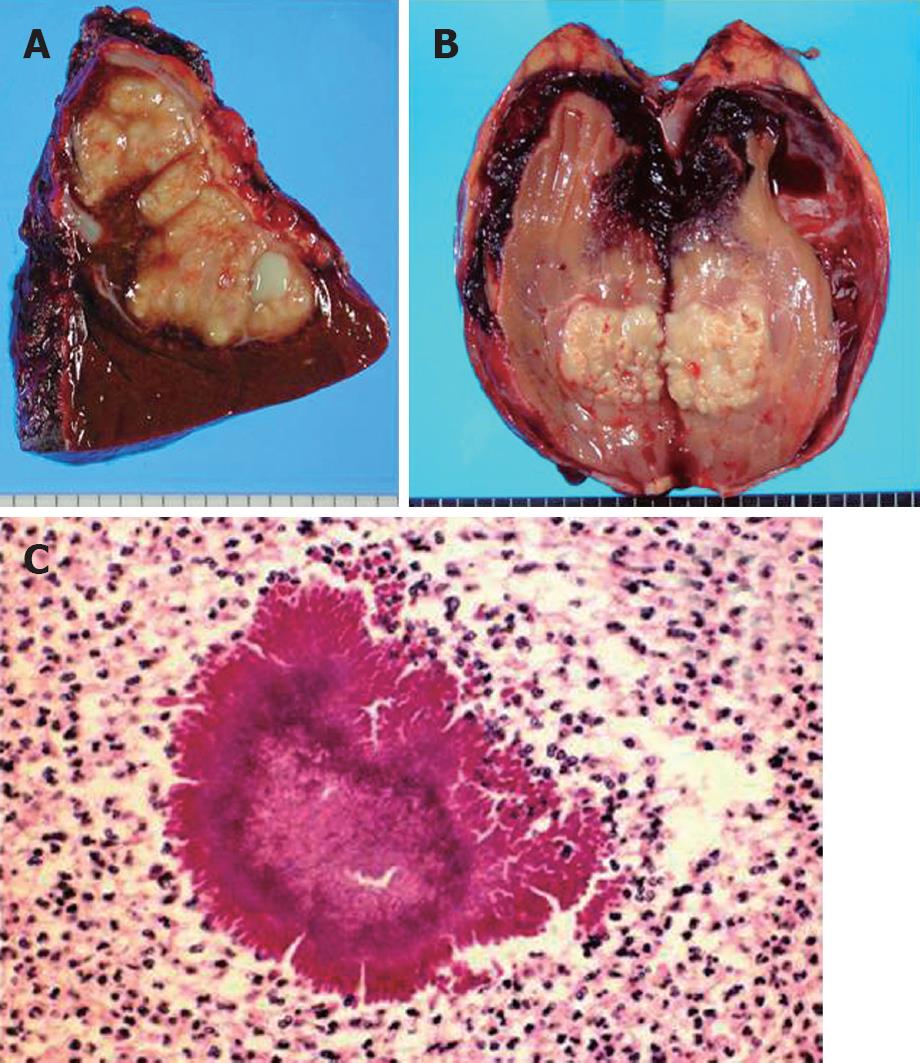

A 49-year-old Japanese woman presented with fever and right lower abdominal pain. She had received a laparoscopic appendectomy for acute gangrenous appendicitis 1 mo before at a nearby hospital. She had no relevant past or family history and did not have an intra-uterine contraceptive device. Mild grade inflammatory findings were noticed on her blood counts and serum biochemistries. On imaging analysis, a liver tumor was found and diagnosed as an abdominal abscess, subsequently treated by percutaneous drainage resulting in no substantial improvement clinically or radiologically, thus prolonging the conservation period remarkably. Bacterial culture of obtained pus showed Enterococcus faecalis. No malignant cells were observed. Although the abscess cavity decreased in size, the whole lesion expanded in segment 5 and 6 of the liver (Figure 1A) and the intrahepatic bile duct was visualized in the contrast study through the drain. Partial hepatectomy and curettage of the abscess wall was finally performed 2 mo after the initial drainage. The lesion in the resected liver was macroscopically a whitish node with capsule and histologically a chronic abscess without malignancy (Figure 2A). However, 3 mo after hepatectomy, she presented with high grade fever again and abscess formation was revealed at the right kidney (Figure 1B) for which a nephrectomy was performed (Figure 2B). The pathological examination of the resected kidney revealed an abscess due to Actinomyces israelii with characteristic “sulfur granules” and subsequently the previous specimen was retrospectively examined which revealed similar pathological findings; at this point actinomycosis was diagnosed (Figure 2C). She received intravenous administration of antibiotics for 3 wk followed by oral antibiotics for 3 mo, including ampicillin, sulbactam and minocycline. The patient is currently alive and well with no sign of recurrence 5 years and 8 mo after the last surgery.

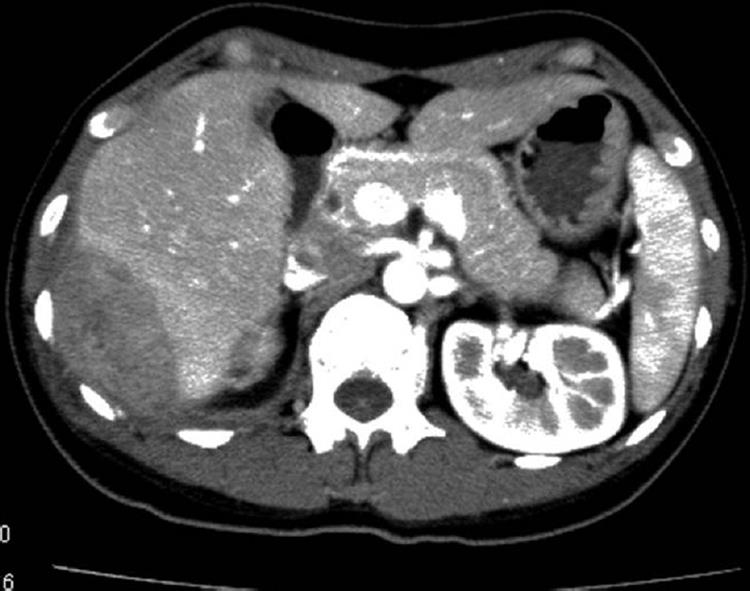

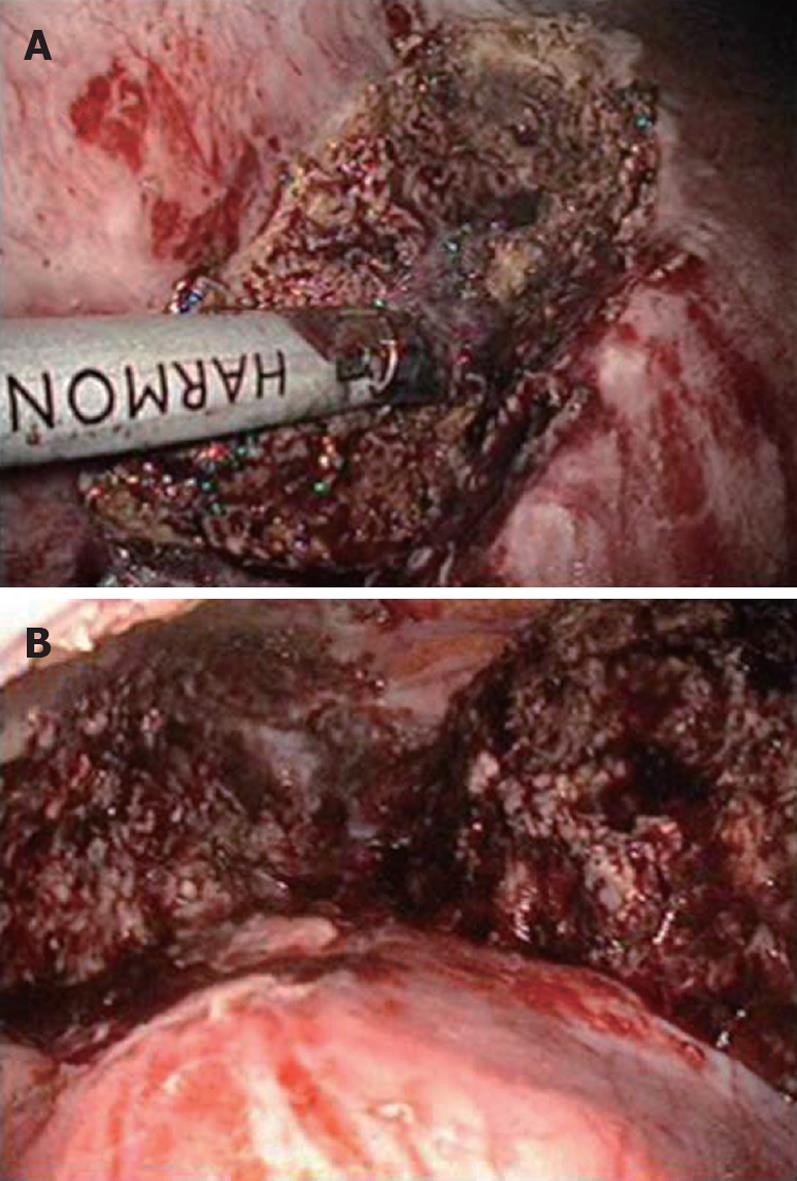

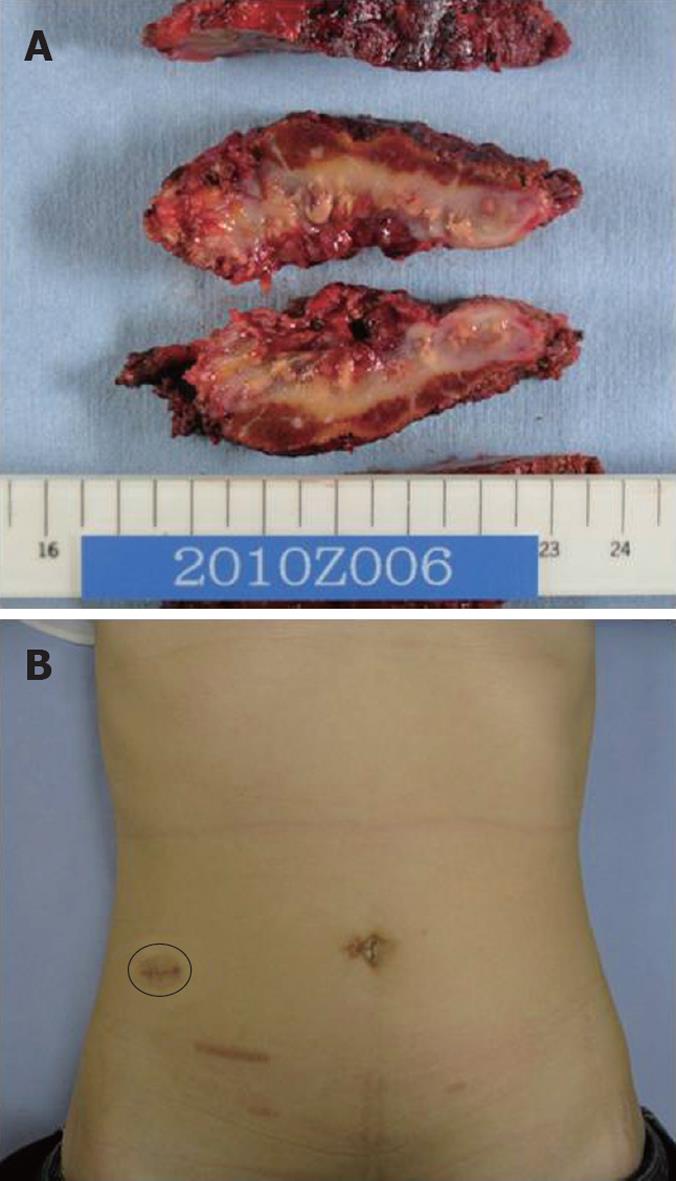

A 41-year-old Japanese woman was referred to our institute for an abdominal mass with mild abdominal pain in the right hypochondrial through flank region and low grade fever persisting for 4 mo. She had received a laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis 9 mo before at a nearby hospital. She had no history of intra-uterine contraceptive device use. An intra-abdominal mass lesion, found at the first hospital, had increased in size at the time of presentation at the second hospital and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography examination (FDG-PET) was performed for suspected malignancy which showed a high standardized uptake value (SUVmax: 11.6) for FDG at the tumor. Laboratory data showed only a mild increase in C-reactive protein and was otherwise normal, including tumor markers, blood count and biochemistry. Abdominal computed tomography (Figure 3) demonstrated a tumor 70 mm × 45 mm between the retroperitoneum and segment 6 of the liver, showing an irregularly circumferentiated, contrast-enhanced cystic structure with heterogenous content inside. From these characteristic clinical course and imaging studies, she was diagnosed as having actinomycosis and was then treated with ampicillin, sulbactam and minocycline. The tumor decreased in size but abnormal C-reactive protein level and mild grade fever persisted; thus she had a laparoscopic resection [using single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) technique] of the tumor (Figure 4). A drain was not placed. Cholecystectomy was also performed using the same single-port simultaneously for known cholecystolithiasis. She was discharged home on postoperative day 10. The resected specimen revealed (Figure 5) intra-abdominal and intrahepatic abscess due to actinomycosis without malignancy. The patient received oral antibiotics postoperatively and is currently doing well with no sign of recurrence 3 mo after the last surgery.

Actinomycosis is a chronic or subacute suppurative granulomatous inflammation caused by the Actinomyces species, mainly Actinomyces israelii, a microaerophilic, anaerobic Gram-positive rod. Since Actinomyces is considered to be saprophytes in the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract and female genital tract, some surgical triggers such as mechanical wounds, operation, placement of intra-uterine contraceptive device and teeth extraction may act to destroy the mucosal barrier function, resulting in facilitation of invasion of the pathogen into deeper tissue from its original habitat. Clinical features are classified into 3 subtypes: cervicofacial, thoracic and abdominal, and advanced type with systemic hematogenous dissemination of pathogen; the last of which sometimes causes a fatal outcome. In the abdominal type, the ileocecal region, including the appendix, is the most frequent site since the swallowed pathogen invading through defect of mucosa, i.e. ulcer lesion, causes the disease. Among the abdominal organs, liver, gall pathways, pancreas, gastro intestines and kidney are involved[2].

The differential diagnosis includes malignancies (such as sarcoma and cholangiocarcinoma), ameboma, inflammatory bowel diseases (such as diverticular disease, intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease) and pathological status within the abdominal muscles[6-8]. Definitive diagnosis is made by identification of this pathogen in the pus. Therefore, when faced with an inflammatory tumor after an episode of appendectomy or significant enterocolitis, actinomycosis should be listed on the differential diagnosis[5,9]. However, diagnostic accuracy by means of microbiological culture and biopsy is reported to be very low, thus making preoperative diagnosis difficult as in our case 1.

With respect to treatment, a natural cure is reported to be rare and early implementation of treatment including antibiotics and/or surgery is necessary[10]. Especially in the case of the systemic type, depending on the organ(s) involved, delay in treatment may be fatal. In this regard, case 1 appeared to be a systemic type with liver and subsequent kidney involvement showing a tendency to spread to the adjacent organ or tissue in which aggressive surgical treatment would be especially required.

While disease of a relatively earlier stage may respond to antibiotics mono-therapy, the majority of reported cases needed surgical intervention in addition to antibiotic administration[6]. Moreover, malignancy can not necessarily be ruled out completely. Although in case 2 in our series actinomycosis was highly suspected from our experience with our first case, surgical extirpation was eventually mandatory due to refractory nature of this case. In fact, the majority of patients shows an increased rate of recurrence after antibiotic therapy without simultaneous surgical resection of the infected area; thus combined therapy of antibiotics and surgery has been advocated as the most efficient treatment[2,6]. In such a situation, a laparoscopic approach would be the best option because of its minimal invasiveness. In fact, this is the first case, to the best our knowledge, to be treated laparoscopically. This procedure is also effective to dispense with cumbersome percutaneous abdominal drainage, enabling a shorter duration of whole treatment process. Furthermore, pretreatment with antibiotics would be beneficial to shrink the tumor to be excised and facilitate the laparoscopic operation as well as therapeutic diagnosis, as in our case 2. However, it should also be kept in mind that if malignancy is suspected during the laparoscopic procedure, immediate conversion to an open method is required.

SILS has been spreading recently as the least invasive procedure in the field of abdominal surgery. We applied this procedure on case 2 with satisfying results in terms of cosmetics and analgesics since even a simple drain insertion would have necessitated a single incision.

In conclusion, abdominal actinomycosis needs to be listed on a differential diagnosis when faced with an abdominal tumor lesion mimicking malignancy and a laparoscopic approach provides modality both of diagnostic and therapeutic effectiveness.

Peer reviewers: Mehmet Fatih Can, Assistant Professor, Gulhane School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Etlik 06018, Ankara, Turkey; Zenichi Morise, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Fujita Health University School of Medicine, 1-98 Dengakugakubo Kutsukakecho, Toyoake AICHI 470-1192, Japan

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Lin YP

| 2. | Wong JJ, Kinney TB, Miller FJ, Rivera-Sanfeliz G. Hepatic actinomycotic abscesses: diagnosis and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:174-176. |

| 3. | Baierlein SA, Wistop A, Looser C, Peters T, Riehle HM, von Flüe M, Peterli R. Abdominal actinomycosis: a rare complication after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1123-1126. |

| 4. | Chen LW, Chang LC, Shie SS, Chien RN. Solitary actinomycotic abscesses of liver: report of two cases. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:104-107. |

| 5. | Islam T, Athar MN, Athar MK, Usman MH, Misbah B. Hepatic actinomycosis with infiltration of the diaphragm and right lung: a case report. Can Respir J. 2005;12:336-337. |

| 6. | Filipović B, Milinić N, Nikolić G, Ranthelović T. Primary actinomycosis of the anterior abdominal wall: case report and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:517-520. |

| 7. | Wagenlehner FM, Mohren B, Naber KG, Männl HF. Abdominal actinomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:881-885. |

| 8. | Meyer P, Nwariaku O, McClelland RN, Gibbons D, Leach F, Sagalowsky AI, Simmang C, Jeyarajah DR. Rare presentation of actinomycosis as an abdominal mass: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:872-875. |

| 9. | Guven A, Kesik V, Deveci MS, Ugurel MS, Ozturk H, Koseoglu V. Post varicella hepatic actinomycosis in a 5-year-old girl mimicking acute abdomen. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:1199-1201. |

| 10. | Saad M, Moorman J. Images in clinical medicine. Actinomyces hepatic abscess with cutaneous fistula. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:e16. |