Published online Aug 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.108963

Revised: June 5, 2025

Accepted: July 7, 2025

Published online: August 27, 2025

Processing time: 121 Days and 1.4 Hours

Anal canal adenocarcinoma with secondary perianal Paget’s disease (PPD) is clinically rare and exhibits atypical symptoms, often misdiagnosed as benign conditions such as hemorrhoids or perianal eczema, leading to delayed treatment. Further summarization of diagnostic and therapeutic key points, as well as reasons for misdiagnosis, is necessary to enhance clinical awareness.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on a 72-year-old female patient with a 2-year history of perianal moisture, pruritus, and hematochezia, who was re

Secondary PPD has a high misdiagnosis rate. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for elderly patients with prolonged perianal symptoms (e.g., pruritus, hematochezia > 6 months) and promptly perform colonoscopy and im

Core Tip: Perianal Paget's disease (PPD), particularly secondary PPD associated with anal adenocarcinoma, is frequently misdiagnosed due to nonspecific symptoms resembling hemorrhoids or eczema. This case highlights a 72-year-old female with a 2-year misdiagnosis history, ultimately confirmed via colonoscopy, biopsy, and immunohistochemistry [IHC; CK7(+)/CK20(+)/CDX2(+)/CEA(+)]. Successful treatment with 3D laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection and extended perianal excision underscores the importance of early IHC testing in refractory perianal symptoms. Key takeaways: (1) Secondary PPD requires high clinical suspicion in elderly patients with chronic perianal lesions; (2) Multimodal diagnostics (endoscopy, biopsy, IHC) are critical to differentiate primary/secondary PPD; and (3) Radical resection ensures oncologic safety, while structured follow-up prevents recurrence.

- Citation: Wu SW, Rong Y, Chen GJ, Cao XS, Xie ZY, Wu B, Huang HC, Wang ZW, Wu XX. Anal adenocarcinoma with perianal Paget's disease: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(8): 108963

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i8/108963.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.108963

Extramammary Paget's disease (EMPD) is a rare epithelial malignancy that constitutes approximately 20%-30% of all Paget's disease cases. This condition primarily develops in regions rich in apocrine glands, particularly the external genitalia and perineal area. Within the spectrum of EMPD, perianal Paget's disease (PPD) accounts for 6.5%-10% of cases. Pathogenetically, PPD is categorized into two distinct subtypes: Primary PPD, originating from perianal epidermal apocrine glands, and secondary PPD, which is commonly associated with concurrent malignancies such as rectal adenocarcinoma, anal canal carcinoma, or urothelial carcinoma[1]. Clinically, PPD often presents with nonspecific symptoms, including perianal moisture, pruritus, erythematous plaques, erosions, superficial ulcerations, and hyperpigmentation. These manifestations frequently mimic benign anorectal disorders like hemorrhoids, anal eczema, or perianal dermatitis, leading to a high misdiagnosis rate. Studies indicate that the average diagnostic delay for PPD exceeds two years[2]. This is particularly concerning for secondary PPD cases, which often coexist with underlying gastrointestinal malignancies. Diagnostic delays in such cases may result in missed therapeutic windows, substantially compromising patient outcomes[3]. Given these clinical challenges, there is an urgent need to improve clinician recognition of PPD, enhance diagnostic precision, and develop effective strategies to prevent misdiagnosis. In the present study, we report a diagnostically complex case of anal canal adenocarcinoma with secondary PPD that was initially misdiagnosed as mixed hemorrhoids over an extended period. The patient was admitted to the General Hospital of the Southern Theater Command, People's Liberation Army of China in January 2024. Through a comprehensive analysis of the misdiagnosis causes and by distilling key diagnostic and therapeutic lessons, we aim to provide clinically relevant insights for the management of PPD.

A 72-year-old female patient was admitted due to "recurrent perianal moisture, pruritus, and hematochezia for 2 years".

The patient developed unexplained perianal moisture and pruritus accompanied by skin ulceration and exudation 2 years ago, which worsened at night and significantly affected sleep. Subsequently, the patient experienced progressive symptoms characterized by bright red blood streaks on toilet paper following defecation. The bleeding was not mixed with stool, and no associated prolapsed masses, dyschezia, or tenesmus were observed.

The patient denied any history of alternating bowel habits (constipation/diarrhea), inflammatory bowel disease, or pelvic floor disorders. During the initial 2-year diagnostic odyssey, the patient's persistent perianal symptoms were recurrently misattributed to benign conditions (''mixed hemorrhoids'' and ''anal pruritus'') at peripheral institutions. Despite undergoing two sessions of sclerotherapy, two hemorrhoidectomies, and prolonged topical therapy (suppositories/corticosteroid ointments), her symptoms not only failed to resolve but progressively exacerbated. Critically, the absence of definitive diagnostic procedures—specifically colonoscopy and histopathological evaluation—at these institutions perpetuated the diagnostic delay until ultimate referral. Over the past three months, the patient experienced worsening perianal pruritus accompanied by progressive skin erosion, exudation, and significantly aggravated hematochezia, severely impairing quality of life. To establish a definitive diagnosis, the patient was admitted to our hospital in January 2024 with preliminary diagnoses of PPD and anal canal tumor.

The patient denied any significant personal or family medical history, including chronic diseases, malignancies, or hereditary disorders.

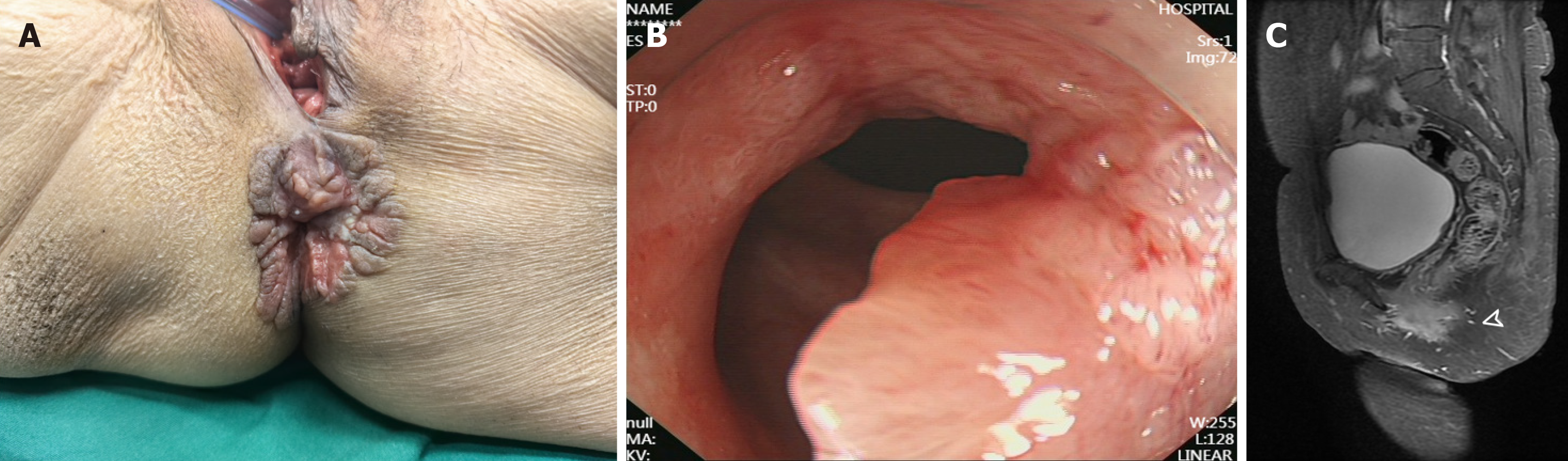

Physical examination revealed extensive moist erythematous lesions with erosion, hyperpigmentation, white scaling, and fissured hyperplasia encircling the anus in a circumferential pattern (approximately 4 cm in diameter). Digital rectal examination identified an irregular ulcerated mass located 1.5 cm above the dentate line on the posterior rectal wall. The lesion exhibited a soft texture, irregular surface, and poorly defined margins, with blood staining noted on the examining glove (Figure 1A).

Routine laboratory examinations revealed no clinically significant abnormalities.

Colonoscopic examination (covering the rectum, sigmoid colon, descending colon, and ascending colon) revealed a semi-circumferential friable and bleeding tumor extending from 3 cm above the anal verge to the anal canal, with multiple biopsies obtained. Pathology of the rectal mucosal biopsy showed atypical glands arranged in papillary and micro

The multidisciplinary team (MDT) comprising general surgery, oncology, and pathology departments conducted a comprehensive evaluation. Given the patient's concurrent malignancy and PPD, abdominoperineal resection (APR) combined with extended perianal lesion excision was ultimately prioritized as the treatment of choice.

The patient's final preoperative diagnosis was "anal canal adenocarcinoma with secondary PPD (cT3N0M0)".

Following comprehensive preoperative evaluation, the patient underwent three-dimensional laparoscopy-assisted APR with extended perianal lesion excision under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, primary reconstruction and closure of the pelvic peritoneum were performed without requiring perianal skin flap transplantation. The perineal wound was primarily repaired and reconstructed (Figure 2A). The resected specimen was submitted for pathological examination. Both gross and histopathological evaluations confirmed negative surgical margins, achieving an R0 resection. Postoperative pathological examination revealed: (Rectoanal tumor and perianal skin) moderately to well-differentiated adenocarcinoma infiltrating the superficial muscular layer (flat-type lesion, approximately 4 cm × 3 cm in size). Microscopic examination of the perianal grayish-white rough area demonstrated nests of atypical cells within squamous epithelium, consistent with EMPD (approximately 7 cm × 1.5 cm in size). Immunohistochemical staining showed: MLH1(+), PMS2(+), MSH2(+), MSH6(+), Ki67 approximately 80%(+), PD-1 lymphocytes approximately 20%(+), and PD-L1(-; Figure 2B and C). The patient recovered well postoperatively without perioperative complications, achieving primary healing of both perianal and perineal wounds, and was successfully discharged on postoperative day 10.

After comprehensive evaluation by the MDT comprising general surgery, medical oncology, radiology, and pathology disciplines, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was not recommended based on the final pathological staging (pT2N0M0 with R0 resection) and absence of high-risk features such as lymph node metastasis. The patient was advised to undergo regular follow-up evaluations every 3 months, consisting of comprehensive physical examinations, serum tumor marker assessments (CEA, CA19-9, and CA-125), contrast-enhanced pelvic MRI, and thoracoabdominal computed tomography scans, supplemented by annual colonoscopic surveillance. At the 12-month follow-up assessment, the patient maintained favorable overall health status with complete resolution of the perianal wound. All measured tumor markers persisted within normal physiological ranges, while serial imaging evaluations conclusively demonstrated absence of both local disease recurrence and distant metastatic spread. Importantly, no stoma-associated complications (including parastomal hernia formation) or perineal/pelvic floor herniation were clinically evident, and the patient consistently reported preserved quality of life parameters throughout the follow-up period.

PPD represents a rare subtype of EMPD, comprising about 20% of EMPD cases yet fewer than 1% of all anorectal conditions[4-6]. In contrast to vulvar or scrotal EMPD, PPD demonstrates more aggressive biological behavior, with invasive disease present at diagnosis in nearly half of cases. Additionally, local recurrence occurs in over one-third of patients, and the disease shows marked potential for lymph node involvement and distant metastasis, collectively contributing to its unfavorable prognosis[5,6]. Recent multicenter data indicate PPD primarily affects patients aged over 65 years, with a male predominance (male-to-female ratio approximately 2.4:1). The average disease duration exceeds two years, and the misdiagnosis rate remains alarmingly high (72.2%), with recent data suggesting that delayed referral and overreliance on clinical impression without biopsy contribute significantly to this trend[2,7]. PPD is frequently misdiagnosed as eczema (48.4%), hemorrhoids (12.9%), or chronic dermatitis (6.4%), with many patients receiving multiple unsuccessful treatments before accurate diagnosis[8]. A JAMA dermatology study reported an average diagnostic delay of 35.7 months, attributed to nonspecific symptoms and the perianal region's anatomical concealment that hinders self-examination[9].

PPD demonstrates varied clinical presentations, most commonly including refractory pruritus, pain, erythematous plaques, erosions, and localized white scaling[10]. The pathognomonic "strawberry-and-cream" appearance may be observed in classic presentations[11]. Histologically, the disease is defined by intraepidermal Paget cells exhibiting large vesicular nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm, frequently arranged in nests that complicate accurate margin assessment[12-14]. Secondary PPD (representing 18.1% of cases) predominantly arises from concomitant malignancies in the rectum, anal canal, or urogenital tract[5]. IHC is indispensable for differentiation: Primary PPD typically expresses CK7(+)/GCDFP-15(+) but lacks CK20, while secondary PPD shows CK7(+)/CK20(+)/CDX2(+) with GCDFP-15(-), indicating likely colorectal adenocarcinoma origin[15-17]. However, IHC alone has diagnostic limitations, necessitating a multimodal assessment—including pelvic MRI, endoscopy, and digital rectal examination—to detect potential underlying malignancies[18]. The staging and management of PPD still follow the 1990 Shutze and Gleysteen classification system (Table 1), which remains the basis for treatment decisions[19]. Although surgical resection is the primary treatment, recurrence rates depend not only on surgical technique but also on adverse prognostic factors, such as advanced age, male sex, perianal/rectovaginal involvement, extensive subclinical spread, lymphovascular invasion, adnexal infiltration, and high p53 expression. Wide local excision carries a high recurrence rate (37.5%), whereas Mohs micrographic surgery, with its superior margin control, reduces recurrence to 11%-22%[20]. In secondary PPD with concurrent anal or rectal carcinoma, extended APR combined with perianal skin excision provides definitive radical treatment[21]. A study confirm that this combined approach significantly lowers local recurrence and improves long-term survival in secondary PPD[22]. Although T2N0M0-stage tumors are generally candidates for sphincter-preserving procedures, this case necessitated APR due to circumferential anal canal involvement and extensive PPD infiltration. Secondary Paget's disease requires wider surgical margins (typically 3-5 cm beyond standard adenocarcinoma resection) and generally contraindicates sphincter-sparing approaches. Furthermore, the coexistence of secondary Paget's disease with rectal adenocarcinoma may signify more aggressive tumor biology and/or advanced disease staging, which is strongly associated with adverse clinical outcomes including diminished survival rates and elevated recurrence risk[3]. Given the significantly elevated recurrence risk in such cases, intensified postoperative surveillance is mandatory. In recent years, molecular targeted therapies have become important treatment options for advanced or recurrent PPD. HER2 (ERBB2) gene amplification is detected in 30%-60% of PPD cases, with HER2-positive tumors showing favorable responses to trastuzumab-based regimens[23]. Additionally, immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 have demonstrated promising efficacy in advanced PPD, further expanding therapeutic options[24-26].

| Stage | Description | Treatment recommendation |

| I | Paget cells confined to perianal dermis and its appendages without carcinoma in situ | WLE |

| II | Paget's disease of epidermis with associated appendageal carcinoma | WLE |

| III | Paget's disease with concurrent rectal/anal canal carcinoma | APR |

| IV | Paget's disease with regional lymph node metastasis | APR + regional lymphadenectomy |

| V | Paget's disease with distant organ metastasis | Chemoradiotherapy + local palliative therapy |

The patient in this case was misdiagnosed for two years, primarily due to the nonspecific nature of the presenting symptoms (perianal moisture, pruritus, and hematochezia), which are commonly attributed to hemorrhoids or eczema. This diagnostic oversight was further compounded by clinicians' limited familiarity with PPD and their failure to perform fundamental examinations, particularly digital rectal evaluation. Moreover, the absence of timely colonoscopy and skin biopsy at referring institutions, coupled with repeated unnecessary hemorrhoid procedures, significantly prolonged the diagnostic process, while the patient's inadequate health literacy delayed appropriate specialist referral. To mitigate such diagnostic errors, a comprehensive multilevel approach is imperative: (1) Heightening clinical suspicion for PPD (especially in malignancy-associated cases) by systematically including it in the differential diagnosis for elderly patients presenting with refractory perianal symptoms lasting more than three months; (2) Implementing standardized diagnostic workflows that incorporate early digital rectal examination, colonoscopy, tissue biopsy, and immunohistochemical profiling (utilizing CK7/CK20/CDX2/CEA/GCDFP-15 markers) to distinguish between primary PPD and secondary manifestations (particularly those of gastrointestinal origin); (3) Establishing MDT collaboration to integrate specialized knowledge from proctology, pathology, and other relevant disciplines; (4) Improving accessibility to advanced pathological and immunohistochemical testing capabilities in primary care settings; and (5) Enhancing patient education initiatives to promote early recognition of warning signs and facilitate prompt specialist consultation.

The clinical insights from this case further underscore that PPD diagnosis necessitates comprehensive pathological evaluation and immunohistochemical analysis, whereas secondary PPD demands radical resection with wide margins

In conclusion, the experience of this case suggests that clinicians need to enhance the early recognition of PPD, strictly standardize the diagnosis and treatment process, and strengthen multidisciplinary cooperation to effectively avoid misdiagnosis and mistreatment of the disease, and maximize the improvement of the patient's prognosis and quality of life.

We appreciate the help of the RCA citation tool (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/) in improving our article. We appreciate the valuable contributions of the general surgery specialists at General Hospital of Southern Theater Command.

| 1. | Morris CR, Hurst EA. Extramammary Paget Disease: A Review of the Literature-Part I: History, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Presentation, Histopathology, and Diagnostic Work-up. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:151-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rastogi S, Thiede R, Sadowsky LM, Hua T, Rastogi A, Miller C, Schlosser BJ. Sex differences in initial treatment for genital extramammary Paget disease in the United States: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:577-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Isik O, Aytac E, Brainard J, Valente MA, Abbas MA, Gorgun E. Perianal Paget's disease: three decades experience of a single institution. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hatta N, Yamada M, Hirano T, Fujimoto A, Morita R. Extramammary Paget's disease: treatment, prognostic factors and outcome in 76 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhu Y, Ye DW, Yao XD, Zhang SL, Dai B, Zhang HL, Shen YJ, Mao HR. Clinicopathological characteristics, management and outcome of metastatic penoscrotal extramammary Paget's disease. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:577-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Onaiwu CO, Salcedo MP, Pessini SA, Munsell MF, Euscher EE, Reed KE, Schmeler KM. Paget's disease of the vulva: A review of 89 cases. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;19:46-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Imaizumi J, Moritani K, Takamizawa Y, Inoue M, Tsukamoto S, Kanemitsu Y. A review of 14 cases of perianal Paget's disease: characteristics of anorectal cancer with pagetoid spread. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Karam A, Dorigo O. Treatment outcomes in a large cohort of patients with invasive Extramammary Paget's disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:346-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cheng JW, Zheng BW, Li JH. Perianal Paget Disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:1239-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hutchings D, Windon A, Assarzadegan N, Salimian KJ, Voltaggio L, Montgomery EA. Perianal Paget's disease as spread from non-invasive colorectal adenomas. Histopathology. 2021;78:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Murata T, Honda T, Egawa G, Kitoh A, Dainichi T, Otsuka A, Nakajima S, Kore-Eda S, Kaku Y, Nakamizo S, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Three-dimensional evaluation of subclinical extension of extramammary Paget disease: visualization of the histological border and its comparison to the clinical border. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:229-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hikita T, Ohtsuki Y, Maeda T, Furihata M. Immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization studies on noninvasive and invasive extramammary Paget's disease. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20:441-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Navarrete-Dechent C, Aleissa S, Cordova M, Hibler BP, Erlendsson AM, Polansky M, Cordova F, Lee EH, Busam KJ, Hollmann T, Lezcano C, Moy A, Pulitzer M, Leitao MM Jr, Rossi AM. Treatment of Extramammary Paget Disease and the Role of Reflectance Confocal Microscopy: A Prospective Study. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:473-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nagai Y, Kazama S, Yamada D, Miyagawa T, Murono K, Yasuda K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Kawai K, Masui Y, Nozawa H, Yamaguchi H, Ishihara S, Kadono T, Watanabe T. Perianal and Vulvar Extramammary Paget Disease: A Report of Six Cases and Mapping Biopsy of the Anal Canal. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:624-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shiomi T, Noguchi T, Nakayama H, Yoshida Y, Yamamoto O, Hayashi N, Ohara K. Clinicopathological study of invasive extramammary Paget's disease: subgroup comparison according to invasion depth. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:589-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Li X, Hu T, Xu X, Wu Z, Zhang X, Wang H, Xu J, Xu F, Guan M. Clinical and pathological characteristics of extramammary Paget's disease: report of 246 Chinese male patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13233-13240. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kodama S, Kaneko T, Saito M, Yoshiya N, Honma S, Tanaka K. A clinicopathologic study of 30 patients with Paget's disease of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaku-Ito Y, Ito T, Tsuji G, Nakahara T, Hagihara A, Furue M, Uchi H. Evaluation of mapping biopsies for extramammary Paget disease: A retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1171-1177.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shutze WP, Gleysteen JJ. Perianal Paget's disease. Classification and review of management: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:502-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Damavandy AA, Terushkin V, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG, Miller CJ, Etzkorn JR, Shin TM, Cappel MA, Mitkov M, Hendi A. Intraoperative Immunostaining for Cytokeratin-7 During Mohs Micrographic Surgery Demonstrates Low Local Recurrence Rates in Extramammary Paget's Disease. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:354-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jung JH, Kwak C, Kim HH, Ku JH. Extramammary Paget Disease of External Genitalia: Surgical Excision and Follow-up Experiences With 19 Patients. Korean J Urol. 2013;54:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Parashurama R, Nama V, Hutson R. Paget's Disease of the Vulva: A Review of 20 Years' Experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:791-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tanaka R, Sasajima Y, Tsuda H, Namikawa K, Tsutsumida A, Otsuka F, Yamazaki N. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 protein overexpression and gene amplification in extramammary Paget disease. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1259-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fowler MR, Flanigan KL, Googe PB. PD-L1 Expression in Extramammary Paget Disease: A Case Series. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nakayama Y, Ogata D, Wada S, Tsuruta S, Matsui Y, Okumura M, Hiki K, Nakano E, Namikawa K, Yamazaki N. Treatment of high tumor mutation burden metastatic extramammary Paget disease with an anti-PD-1 antibody. J Dermatol. 2023;50:e396-e397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gatalica Z, Vranic S, Krušlin B, Poorman K, Stafford P, Kacerovska D, Senarathne W, Florento E, Contreras E, Leary A, Choi A, In GK. Comparison of the biomarkers for targeted therapies in primary extra-mammary and mammary Paget's disease. Cancer Med. 2020;9:1441-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |