INTRODUCTION

Patients after surgery for malignant tumors frequently experience a range of psychiatric and psychological disorders due to factors such as tumor severity, medical economic burdens, physiological changes, and shifts in social and family roles (for example, leaving one’s job position). Getie et al[1] showed that among cancer survivors globally, the overall prevalence of depression is 33.16% (95% confidence interval: 27.59-38.74), while anxiety affects 30.55% (95% confidence interval 24.04-37.06). Similarly, post-surgery gastric cancer patients face both physical and psychological challenges, with depression notably obstructing recovery. The incidence of depression in gastric cancer patients is elevated. A small-sample survey from China reported a prevalence of 8.6% within 2-3 days among post-surgery gastric patients[2]. Liu et al[3] also evaluated the depressive status of 226 patients who underwent gastric cancer surgery, including preoperative baseline (M0), 12 months postoperatively (M12), 24 months postoperatively (M24), and 36 months postoperatively (M36). It was found that the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression scores in these patients gradually increased from M0 to M36. This indicates that psychological issues following gastric cancer surgery are not merely short-term but become more severe over time. Another cohort study by Han[4] found that gastric cancer patients had significantly higher Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression scores (6.9 ± 3.5), compared to healthy controls (4.2 ± 2.6), with a depression prevalence of 33.5% vs 10.0% in controls. This study also demonstrated that patients who were suffered with depression had much shorter disease-free survival (P = 0.016) and overall survival (P = 0.022) compared to those without mental and psychological disorders among gastric cancer patients with the same stage. Moreover, due to potential differences in socioeconomic status, awareness of mental health, and access to psychological therapy, some patients after gastric cancer surgery may not receive effective psychological treatment. Consequently, managing depression following gastric cancer surgery is of paramount importance. This article aims to provide an overview of the mental and psychological health challenges that may arise after gastric cancer surgery, the mechanisms of Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics in microbiology, immunology, and neurology, and their clinical efficacy in restoring gastrointestinal function, enhancing immunity, and improving nutritional status during postoperative recovery.

PSYCHOLOGICAL HEALTH ISSUES AFTER GASTRIC CANCER SURGERY: AN UNDERESTIMATED BARRIER TO RECOVERY

The psychological well-being of gastric cancer patients post-surgery need to receive more attention, because these issues not only affect mental states but may also delay physical recovery. Studies have identified a spectrum of psychological challenges in this population. Depression is among the most prevalent, with incidence rates exceeding those in the general population[4]. Contributing factors include the tumor severity, changes in body image due to surgery, economic burdens, family condition drastic, dietary adjustments and fear of recurrence. A study on gastrointestinal cancer patients by Lv et al[5] found that approximately 30% of the patients experienced chronic psychological stress post-surgery, significantly impacting recovery quality. While the long-term incidence of depression in patients with gastric cancer can be as high as 40%. This rate is higher than that observed in patients with other types of malignancies, such as ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer[3]. This finding suggests that compared with patients with other malignant tumors, those with gastric cancer experience disproportionately high levels of psychological distress. Anxiety is another common issue, with patients often preoccupied with concerns about disease progression, treatment efficacy, and future uncertainties, potentially leading to reduced sleep quality and treatment adherence. Additionally, patients may struggle to adapt to new physical conditions and lifestyle changes, which is called adjustment disorder, such as dietary restrictions and associated weight fluctuations after gastric cancer surgery. Some patients may even exhibit symptoms resembling post-traumatic stress disorder, particularly after major surgery or disease-related trauma. These psychological issues carry social consequences, including strained family relationships, diminished social functioning, and increased economic burdens. Evidence suggests that psychological stress may indirectly influence cancer prognosis by modulating the immune system and lifestyle behaviors[6].

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS OF BIFIDOBACTERIUM TRIPLE VIABLE PROBIOTICS IN TREATING POSTOPERATIVE DEPRESSION IN GASTRIC CANCER

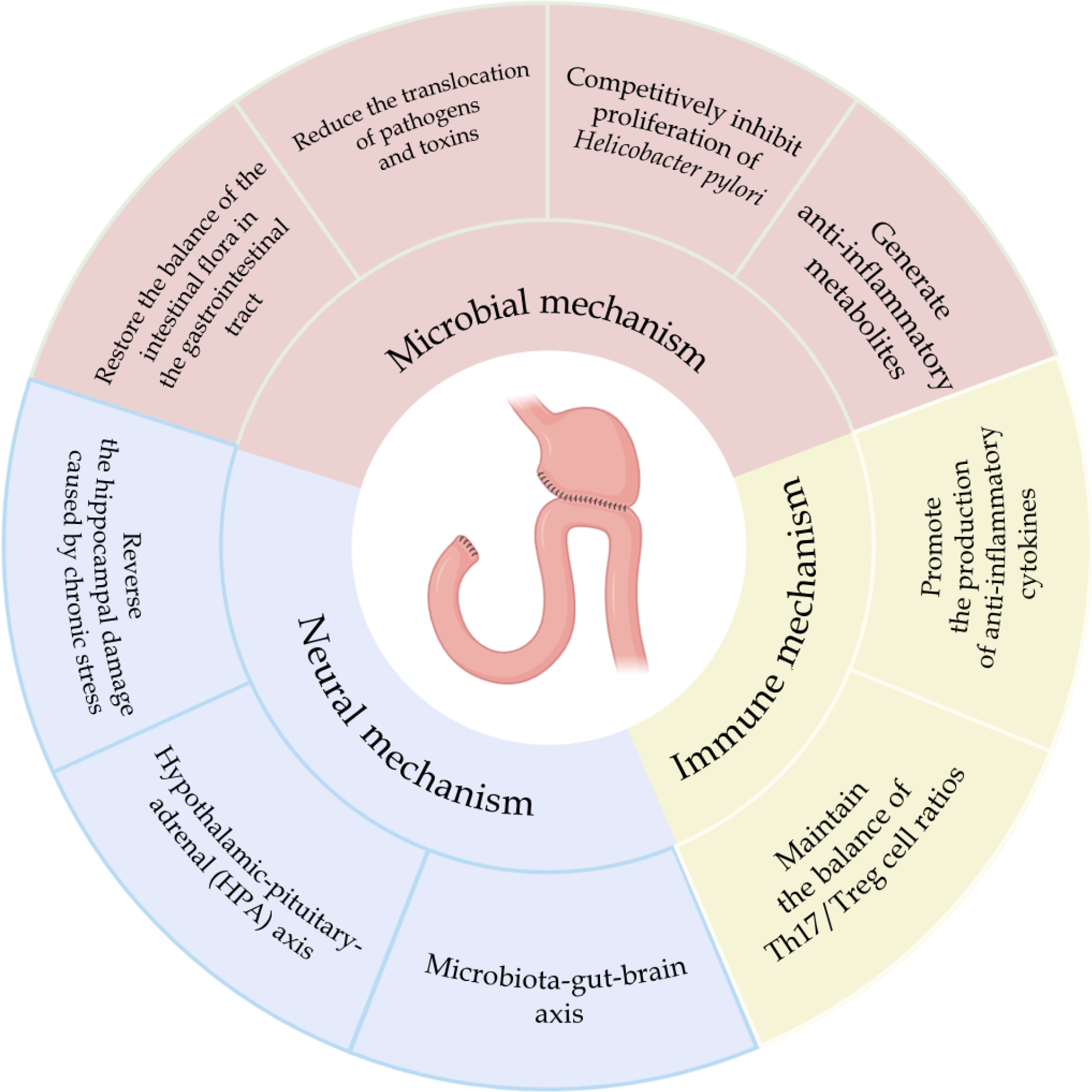

Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics typically comprise three live bacterial strains (e.g., Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Enterococcus faecalis). Given that Bifidobacterium preparations are the most commonly used probiotics, and Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics is the most prevalent probiotic pharmaceutical preparation on the market, it is both practical and representative to explore the impact of Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics on postoperative depression in gastric cancer patients. When combined with mirtazapine, their potential in alleviating postoperative depression in gastric cancer patients may involve microbiological, immunological, and neurological mechanisms (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Potential mechanisms of Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics in treating postoperative depression in gastric cancer.

From a microbiological perspective, gastric cancer surgery and postoperative prophylactic antibiotics often disrupt the gut microbiota. Bifidobacterium can restore a balanced gut microbiome by competitively excluding pathogenic bacteria[7], forming a protective barrier on the gastrointestinal mucosa. This barrier reduces pathogen and toxin translocation, which further lowers systemic inflammation[8]. This effect is also evident in competitively inhibiting Helicobacter pylori infections, with studies showing that probiotic supplementation enhances eradication rates and reduces postoperative adverse reactions[8]. Moreover, Bifidobacterium produces beneficial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which possess anti-inflammatory properties and reinforce gastrointestinal barrier function[9].

Immunologically, Bifidobacterium may regulate local cytokine levels, contributing to immune modulation. The distribution and abundance of microbial community in the mucosal layer may directly influence local immune regulation (such as cytokine levels) and inflammatory responses[10]. Related research indicates that Bifidobacterium can promote anti-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., interleukin (IL)-10] while suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α), mitigating postoperative inflammation[11,12]. Surgical trauma in gastric cancer can increase Th17 cells and decrease Treg cells, amplifying local inflammation and disrupting the Th17/Treg balance. This imbalance may elevate postoperative infection risks, delay healing, and increase cancer recurrence. Chronic long-term stress may also increase cancer susceptibility by suppressing protective T cells[13]. Specific Bifidobacterium strains have been shown to induce regulatory Treg cells, reducing local inflammation and accelerating incision healing[14]. These processes collectively enhance postoperative recovery and reduce complications in gastric cancer patients. As a pharmacological basis for Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics, these positive therapeutic outcomes can improve patients’ postoperative mood and alleviate depression severity.

From a neurological standpoint, the gut microbiota communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve, immune system, and metabolites, a pathway known as the microbiota-gut-brain axis. For example, a study by Zhao et al[15] have shown that aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands (such as indole-3-propionic acid) produced by the metabolism of tryptophan by gut microbiota can regulate immune homeostasis and affect serotonin synthesis. Bifidobacterium modulates tryptophan levels, increasing the availability of 5-hydroxytryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, in the gut and serum, which can ameliorate depressive symptoms[14,16]. Additionally, Bifidobacterium may mitigate depression by regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Hippocampal damage impairs hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis negative feedback, elevating cortisol secretion and creating a vicious cycle linked to psychiatric disorders like depression. Reports suggest that Bifidobacterium, via SCFAs (e.g., butyrate), inhibits histone deacetylase activity, upregulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression, reversing stress-induced hippocampal damage, and reducing depression severity[17,18].

CLINICAL EFFICACY OF BIFIDOBACTERIUM TRIPLE VIABLE PROBIOTICS: HOLISTIC BENEFITS BEYOND DEPRESSION TREATMENT

The therapeutic effects of Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics combined with mirtazapine in gastric cancer postoperative recovery extend to gastrointestinal function restoration, immune enhancement, and nutritional improvement. These benefits support overall physical and psychological recovery. Post-gastric cancer surgery, patients commonly experience gastrointestinal dysfunction, including dysphagia, heartburn, and nutritional deficits due to loss of food storage capacity, severely compromising quality of life. Bifidobacterium restores healthy microbial balance and promotes SCFAs production, improving digestion and gastrointestinal motility[19]. A study by Liu et al[20] demonstrated that probiotic use post-gastric cancer surgery significantly reduces diarrhea incidence, accelerates gastrointestinal recovery (e.g., earlier first flatus and defecation, shorter hospital stays), and lowers economic costs. Surgical trauma often suppresses immune function, but oral Bifidobacterium administration can stimulate natural killer and T-cell activity, bolstering postoperative infection defenses[21]. Nutritional challenges during recovery, stemming from impaired digestion and tumor-related consumption, can hinder progress, yet Bifidobacterium enhances protein absorption, significantly elevating albumin (88.75% increase, P < 0.05) and total protein levels (88.63% increase, P < 0.01) compared to placebo, signaling improved prognosis[19].

CONCLUSION

The impact of postoperative depression on gastric cancer recovery is well-recognized as a critical prognostic factor. The efficacy of Bifidobacterium triple viable probiotics in managing depression has been substantiated at both molecular and clinical levels. The study by Lu et al[22] also demonstrated that the combination of Bifidobacterium triple viable bacteria-assisted mirtazapine is more effective in treating postoperative depression in gastric cancer patients than the monotherapy with mirtazapine, which is commonly used in clinical practice. In the future, combining these probiotics with antidepressants may become a standard approach in postoperative gastric cancer care. However, further long-term, multicenter clinical trials are needed to validate these effects. Recent studies by Huang et al[23] and Du et al[24] have also shown that gut microbiota, such as Akkermansia muciniphila, can enhance the efficacy of programmed death 1 inhibitors by activating specific immune pathways. This suggests that appropriate probiotic strains could serve as biomarkers for predicting immunotherapy responses or as adjunctive therapeutic targets. Future research may focus on personalized probiotic treatment regimens guided by gut microbiota characteristics, genetic factors, and cancer subtypes, or in combination with novel targeted antibiotics such as zosurabalpin to suppress other strains in the gastrointestinal tract, which may improve the therapeutic efficacy for post-gastrectomy depression in gastric cancer patients.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Gao YZ; Krstulović J; Rajpoot A S-Editor: Bai Y L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH