Published online Mar 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i3.95983

Revised: August 2, 2024

Accepted: October 30, 2024

Published online: March 27, 2025

Processing time: 306 Days and 16.8 Hours

Diverting stoma (DS) is routinely proposed in intersphincteric resection for ultra

To select patients who may not require DS.

This study enrolled 505 consecutive patients, including 84 who underwent stoma-free (SF) intersphincteric resection. After matching, patients were divided into SF

The AL rate was greater in the SF group than in the DS group (12.8% vs 2.6%, P = 0.035). Male sex [(odds ratio (OR) = 2.644, P = 0.021], neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) (OR = 6.024, P < 0.001), and tumor height from the anal verge ≤ 4 cm (OR = 4.160, P = 0.007) were identified as independent risk factors. Preservation of the left colic artery (LCA) was protective in both the total cohort (OR = 0.417, P = 0.013) and the SF cohort (OR = 0.312, P = 0.027). The female patients who did not undergo nCRT and had preservation of the LCA experienced a significantly lower incidence of AL (2/97, 2.1%). The 3-year overall survival or disease-free survival did not significantly differ be

Female patients who do not receive nCRT may avoid the need for DS by preserving the LCA without increasing the risk of AL or compromising oncological outcomes.

Core Tip: This study aimed to investigate suitable patient selection and operative strategies by comparing the surgical results and oncological outcomes between stoma-free and diverting stoma intersphincteric resection. Our study makes a significant contribution to the literature because we found female patients without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy could be exempted from diverting stomas by preserving the left colic artery without compromising anastomotic leakage risk and oncological outcomes.

- Citation: Hu G, Ma J, Qiu WL, Mei SW, Zhuang M, Xue J, Liu JG, Tang JQ. Patient selection and operative strategies for laparoscopic intersphincteric resection without diverting stoma. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(3): 95983

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i3/95983.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i3.95983

Intersphincteric resection (ISR) is a sphincter-preserving surgical technique designed to maintain anal function in patients with ultralow rectal cancers. However, anastomotic leakage (AL) is a serious complication associated with laparoscopic ISR (Ls-ISR), leading to prolonged hospital stays, severe abdominal infections, the need for permanent stomas, and even mortality[1-6]. AL is a multifactorial complication that is particularly prevalent in patients with tumors located in the lower rectum, which has a relatively high incidence risk[7-9]. Diverting the bowel contents can help prevent mechanical pressure and fecal contamination at the anastomotic site. This intervention reduces the risk of AL, which is associated with severe clinical symptoms and the need for reoperation[10,11].

A diverting stoma (DS) is a double-edged sword. Although it reduces the risk of AL and associated complications, it also has significant disadvantages, including peristomal inflammation, stoma prolapse, delayed closure, and the possi

The effects of DS on anal function and long-term oncological outcomes also warrant further investigation. However, few studies have focused on selecting a cohort of patients with a low risk of AL who could undergo Ls-ISR for ultralow rectal cancer without DS. Identifying such a cohort could reduce the stoma rate without increasing the risk of AL, thereby decreasing the economic burden, minimizing stoma-related complications, and ultimately improving the quality of life for these patients. We conducted a large retrospective case-matched cohort study to evaluate the short-term and onco

We retrospectively collected data from patients with ultralow rectal cancer who underwent Ls-ISR at a single center between January 2012 and June 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Ultralow rectal cancer with tumors located less than 5 cm from the anal verge (AV); (2) Ls-ISR surgery; and (3) Radical resection of the tumor. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Abdominoperineal resection or Hartmann’s procedure; and (2) Combined organ resection.

Multidisciplinary team meetings determined the treatment strategies for each patient, including the need for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT). Our preferred approach was a long course of preoperative chemoradiotherapy based on 5-fluorouracil, with a radiation protocol of 45 Gy in 25 fractions followed by a 5.4 Gy boost, for a total of 50.4 Gy.

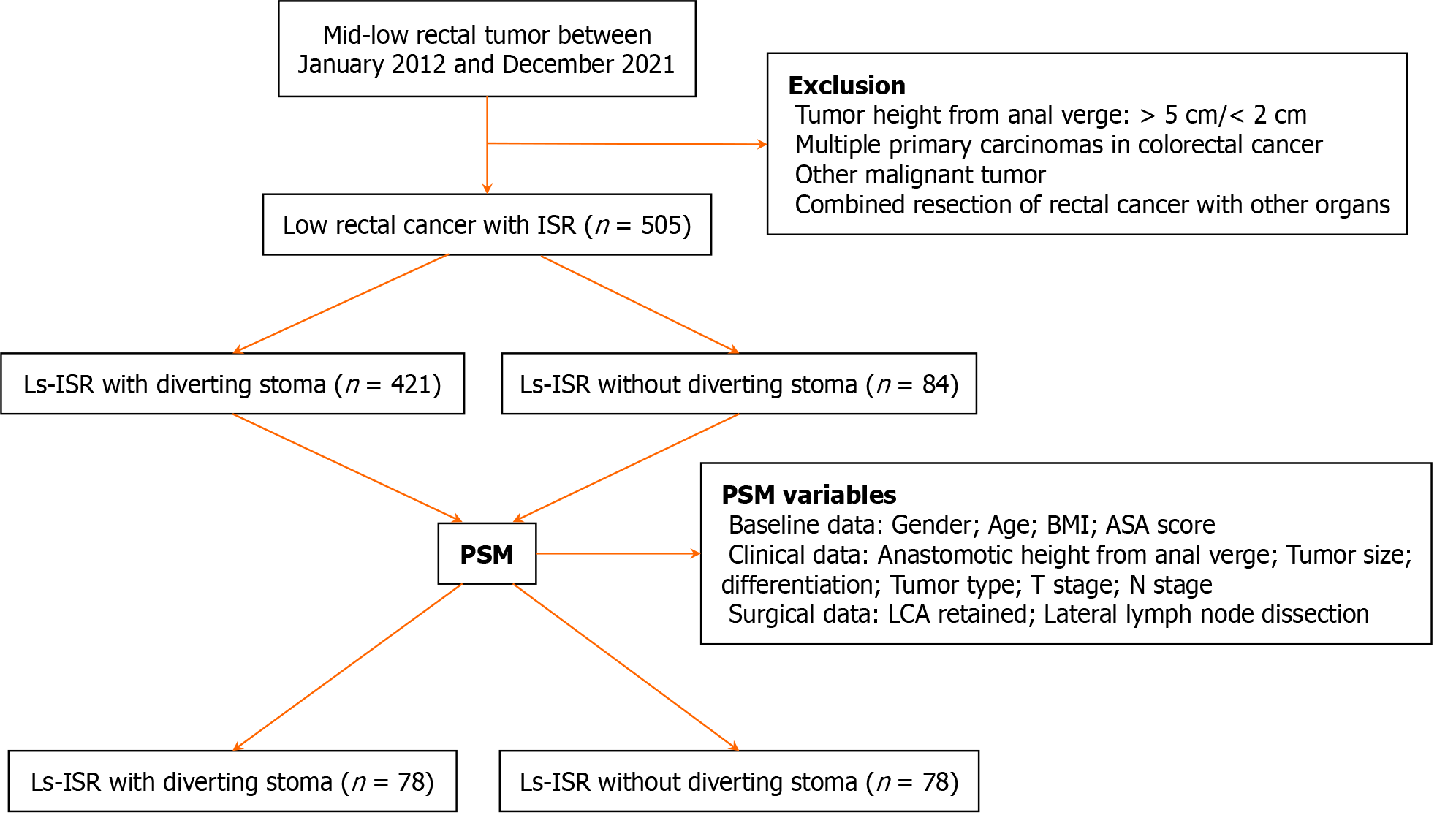

In total, 505 consecutive patients were enrolled in this study (Figure 1). Complications were defined as grade II or higher according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. All patients provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (2020149).

The transabdominal team conducted a standard total mesorectal excision, ensuring careful preservation of the bilateral hypogastric nerves and associated neurovascular bundles. The dissection followed the intersphincteric plane between the puborectalis muscle and the internal anal sphincter and was performed with precision and direct visualization. Meanwhile, the perineal team accessed the anus, dilated the anal canal to approximately three finger widths, and em

After closing the anal orifice at least 1 cm below the tumor, the internal sphincter was circumferentially incised, and dissection along the intersphincteric plane was conducted. This dissection continued cephalad to connect with the transabdominal team. Upon removing the distal rectum through the anus, the sigmoid colon was transected 15 cm above the superior tumor margin, and the specimen was extracted. The surgical site was then irrigated with a 5% iodophor solution.

A coloanal anastomosis was subsequently performed. Intraoperative frozen-section pathology was usually necessary to verify the distal resection margin status if it was less than 1 cm or potentially positive. The decision to perform a DS was made by the surgeon in consultation with the patient during the procedure. If a DS was indicated, a loop ileostomy was created in the right lower abdomen.

Diagnosis was made based on clinical symptoms, such as pain, fever, tachycardia, peritonitis, or abnormal drainage, and radiological findings, such as fluid- or gas-containing collections observed on CT scans. The ISGRC grading system was used to assess the severity of AL as follows[18]: Grade A refers to radiological leakage that is asymptomatic and does not necessitate any intervention; grade B involves leakage that requires active management but does not require surgical reoperation, such as the use of antibiotics or radiological/endoscopic interventions; and Grade C signifies a severe leakage that mandates reoperation.

We collected basic clinical and pathological characteristics of patients, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), nCRT, diabetes status, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, tumor distance from the AV, differentiation status, maximal tumor diameter, (y) pT stage, (y) pN stage, (y) pTNM stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 8th edition), and AL. We also recorded perioperative outcomes, including operative time, blood loss, conversion to open surgery, postope

Follow-up was conducted every 3 months for the first 2 years, every 6 months for the next 3 years, and annually thereafter. At each visit, patients underwent a physical examination, serum carcinoembryonic antigen level measurement, and abdominopelvic magnetic resonance imaging or CT.

The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze differences between the primary and validation cohorts. Variables with a P value < 0.100 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate analyses. A greedy matching algorithm, with a caliper width equal to 0.20 of the standard deviation of the logit transformation of the estimated propensity score, was applied for propensity score matching (PSM)[19]. Propensity scores were estimated using variables such as sex, age, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, maximum tumor diameter, clinical (or pathological) stage, preoperative treatment, height of the anastomotic site from the AV, and left colic artery (LCA) retention. To avoid multicollinearity, the height of the lower edge of the tumor from the AV was not included in the models because it was correlated with the height of the anastomotic site from the AV. The estimated propensity score distribution was similar between the two groups, with no extreme outliers. The DS and stoma-free (SF) groups were matched at a 1:1 ratio using PSM.

Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, with the AL rate as the outcome variable at a significance level of 5%. All the statistical analyses were two-sided, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. R software (version 4.3.2) and SPSS software (version 25.0) were used for the statistical analyses.

A total of 505 patients, including 317 males (64.8%) and 188 females (35.2%), were analyzed. DS was performed on 421 patients (83.4%). The median age was 60 years (range 20-84) in the DS group and 64 years (range 23-84) in the SF group. In the baseline cohort (n = 505), the DS and SF groups significantly differed in terms of age over 60 years (51.6% vs 70.2%, P = 0.003), nCRT (14.7% vs 3.6%, P = 0.009), height of the tumor from the AV (4.0 cm vs 4.5 cm, P < 0.001), height of the anastomotic site from the AV (2.00 cm vs 2.50 cm, P < 0.001), and LCA retention (48.7% vs 72.6%, P < 0.001). The two groups did not significantly differ in terms of poor differentiation (P = 0.216), median maximal tumor size (P = 0.628), or TNM stage (P = 0.659).

After PSM at a 1:1 ratio, 156 patients (78 with DS and 78 with SF) were included. All variables were statistically balanced between the two groups after PSM (Table 1).

| Variables | Before PSM | P value | After PSM | P value | ||

| DS (n = 421) | SF (n = 84) | DS (n = 78) | SF (n = 78) | |||

| Gender | 0.042 | 0.521 | ||||

| Male | 273 (64.8) | 44 (52.4) | 34 (43.6) | 39 (50.0) | ||

| Female | 148 (35.2) | 40 (47.6) | 44 (56.4) | 39 (50.0) | ||

| Age, median (range) years | 60.0 (20.0, 84.0) | 64.0 (23.0, 84.0) | 0.003 | 64.0 (31.0, 82.0) | 64.0 (33.0, 84.0) | 1 |

| < 60 | 204 (48.4) | 25 (29.8) | 25 (32.1) | 25 (32.1) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 217 (51.6) | 59 (70.2) | 53 (67.9) | 53 (67.9) | ||

| BMI, median (range) kg/m2 | 23.7 (14.5, 32.9) | 23.8 (17.8, 34.4) | 1 | 23.9 (17.1, 29.3) | 23.7 (17.8, 34.4) | 1 |

| < 25 | 270 (64.1) | 54 (64.3) | 51 (65.4) | 52 (66.7) | ||

| ≥ 25 | 151 (35.9) | 30 (35.7) | 27 (34.6) | 26 (33.3) | ||

| ASA score | 0.005 | 0.744 | ||||

| I-II | 408 (96.9) | 75 (89.3) | 74 (94.9) | 72 (92.3) | ||

| III | 13 (3.1) | 9 (10.7) | 4 (5.1) | 6 (7.7) | ||

| Diabetes | 1 | 0.811 | ||||

| Yes | 55 (13.1) | 11 (13.1) | 9 (11.5) | 11 (14.1) | ||

| No | 366 (86.9) | 73 (86.9) | 69 (88.5) | 67 (85.9) | ||

| Tumor size, median (range) mm | 35.0 (10.0, 120.0) | 35.0 (15.0, 80.0) | 0.628 | 35.0 (20.0, 90.0) | 35.0 (15.0, 80.0) | 0.958 |

| > 35 | 209 (49.6) | 41 (48.8) | 32 (41.0) | 36 (46.2) | ||

| ≤ 35 | 212 (50.4) | 43 (51.2) | 46 (59.0) | 42 (53.8) | ||

| Differentiation status | 0.216 | 0.277 | ||||

| Poor | 65 (15.4) | 8 (9.5) | 10 (12.8) | 5 (6.4) | ||

| Well-moderate | 356 (84.6) | 76 (90.5) | 68 (87.2) | 73 (93.6) | ||

| Tumor type | 0.944 | 1 | ||||

| Ulcer | 281 (66.7) | 57 (67.9) | 57(73.1) | 57(73.1) | ||

| Protrusion | 140 (33.3) | 27 (32.1) | 31(26.9) | 31(26.9) | ||

| pT stage | 0.362 | 0.255 | ||||

| 0-2 | 181 (43.0) | 31 (36.9) | 36 (46.2) | 28 (35.9) | ||

| 3 | 240 (57.0) | 53 (63.1) | 42 (53.8) | 50 (64.1) | ||

| pN stage | 0.782 | 0.104 | ||||

| N+ | 150 (35.6) | 28 (33.3) | 16 (20.5) | 26 (33.3) | ||

| N0 | 271 (64.4) | 56 (66.7) | 62 (79.5) | 52 (66.7) | ||

| M stage | 1 | 1 | ||||

| M1 | 8 (1.9) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| M0 | 413 (98.1) | 83 (98.8) | 77 (98.7) | 77 (98.7) | ||

| pTNM stage | 0.659 | 0.104 | ||||

| I-II | 154 (36.6) | 28 (33.3) | 16 (20.5) | 26 (33.3) | ||

| III-IV | 267 (63.4) | 56 (66.7) | 62 (79.5) | 52 (66.7) | ||

| nCRT | 0.009 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 62 (14.7) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) | ||

| No | 359 (85.3) | 81 (96.4) | 74 (94.9) | 75 (96.2) | ||

| Tumor height from anal verge, median (range) cm | 4.0 (3.5-4.0) | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) | < 0.001 | 4.0 (4.0-4.5) | 4.0 (4.0-4.5) | 0.412 |

| ≤ 4.0 | 343 (81.5) | 41 (48.8) | 48 (61.5) | 39 (50.0) | ||

| > 4.0 | 68 (18.5) | 43 (51.2) | 30 (38.5) | 39 (50.0) | ||

| Anastomotic height from anal verge, median (range) cm | 2.00 (0.50, 4.00) | 2.50 (1.00, 4.00) | < 0.001 | 2.00 (1.00, 4.00) | 2.50 (1.00, 4.00) | 1 |

| ≤ 3.0 | 406 (96.4) | 73 (86.9) | 72 (92.3) | 72 (92.3) | ||

| > 3.0 | 15 (3.6) | 11 (13.1) | 6 (7.7) | 6 (7.7) | ||

| LCA retention | < 0.001 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 205 (48.7) | 61 (72.6) | 54 (69.2) | 55 (70.5) | ||

| No | 216 (51.3) | 23 (27,4) | 24 (30.8) | 23 (29.5) | ||

| Lateral lymph node dissection | 0.260 | 0.247 | ||||

| Yes | 51 (12.1) | 6 (7.2) | 9 (11.5) | 4 (5.1) | ||

| No | 370 (87.9) | 78 (92.8) | 69 (88.5) | 74 (94.9) | ||

| Hb (g/L) | 0.911 | 0.802 | ||||

| ≥ 120 | 366 (86.9) | 74 (88.1) | 70 (89.7) | 68 (87.2) | ||

| < 120 | 55 (13.1) | 10 (11.9) | 8 (10.3) | 10 (12.8) | ||

| ALB (g/L) | 0.328 | 0.342 | ||||

| ≥ 35.0 | 334 (79.3) | 62 (73.8) | 63 (80.8) | 57 (73.1) | ||

| < 35.0 | 87 (20.7) | 22 (26.2) | 15 (19.1) | 21 (26.9) | ||

| CEA (μg/L) | 0.122 | 0.561 | ||||

| > 5.0 | 134 (31.8) | 19 (22.6) | 15 (19.2) | 19 (24.4) | ||

| ≤ 5.0 | 287 (68.2) | 65 (77.4) | 63 (80.8) | 59 (75.6) | ||

Before PSM, the operative time in the DS group was longer than that in the SF group (172 min vs 171 min, P = 0.015). Although the total AL rate in the DS group was lower than that in the SF group, this difference was not statistically significant (7.6% vs 13.1%, P = 0.099). The rates of grade III postoperative complications (3.6% vs 9.5%, P = 0.035) and grade C AL (0.5% vs 6.0%, P < 0.001) significantly differed between the groups. Additionally, the DS group had a significantly higher completion rate of postoperative chemotherapy (86.8% vs 59.0%, P < 0.001) and a higher rate of permanent stoma (11.2% vs 2.3%, P < 0.001) than the SF group.

After PSM, significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of grade III postoperative complications (2.6% vs 10.3%, P = 0.050) and total AL rates (2.6% vs 12.8%, P = 0.035). However, the incidence of grade C AL (0% vs 6.4%, P = 0.069) was not significantly different. The operative time (P = 0.109), completion rate of adjuvant chemotherapy (P = 0.738), or incidence of permanent stoma (P = 0.521) did not significantly differ after PSM.

The estimated blood loss, reoperation rate, postoperative hospital stay, and incidence of rectovaginal fistulas and anastomotic stricture did not differ between the two groups before and after PSM (Table 2).

| Variables | Before PSM | P value | After PSM | P value | ||

| DS (n = 421) | SF (n = 84) | DS (n = 78) | SF (n = 78) | |||

| Operative time, median (range) min | 172 (90, 335) | 171 (85, 485) | 0.015 | 174 (90, 335) | 168 (90, 480) | 0.109 |

| Blood loss, median (range) mL | 50 (20, 800) | 50 (5, 500) | 0.862 | 50 (10, 200) | 50 (5, 500) | 0.611 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Postoperative complication | 58 (13.8) | 16 (19.0) | 0.212 | 12 (15.4) | 15 (19.2) | 0.481 |

| CD grade I-II | 43 (10.2) | 8 (9.5) | 0.516 | 10 (12.8) | 7 (9.0) | 0.602 |

| CD grade ≥III | 15 (3.6) | 8 (9.5) | 0.035 | 2 (2.6) | 8 (10.3) | 0.050 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 32 (7.6) | 11 (13.1) | 0.099 | 2 (2.6) | 10 (12.8) | 0.035 |

| Grade A-B | 30 (7.1) | 6 (7.1) | 0.996 | 2 (2.6) | 5 (6.4) | 0.439 |

| Grade C | 2 (0.5) | 5 (6.0) | < 0.001 | 0 (0) | 5 (6.4) | 0.069 |

| Ileus | 17 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 0.123 | 5 (6.4) | 0 (0) | 0.069 |

| Hemorrhage postoperation | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.370 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 0.316 |

| Mortality | 2 (0.5) | 1 (1.2) | 0.999 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0.669 |

| Reoperation | 6 (1.4) | 5 (6.0) | 0.074 | 0 (0) | 5 (6.4) | 0.069 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (day) | 9 (4-51) | 11 (4-37) | 0.070 | 10 (5-30) | 12 (6-37) | 0.275 |

| Anastomosis recurrence | 8 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0.427 | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0.477 |

| Rectovaginal fistula | 4 (1.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0.363 | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.998 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 21 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 0.206 | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0.477 |

| Completion rate of postoperative chemotherapy | 191/220 (86.8) | 23/39 (59.0) | < 0.001 | 22/25 (88.0) | 20/24 (88.9) | 0.933 |

| Permanent stoma | 47 (11.2%) | 2 (2.3%) | < 0.001 | 5 (6.4) | 2 (2.6) | 0.521 |

In the univariable logistic regression analysis, male sex (OR = 2.883, 95%CI: 1.310-6.343, P = 0.009), BMI ≥ 25 kg/m² (OR = 1.899, 95%CI: 1.020-3.536, P = 0.043), and nCRT (OR = 4.805, 95%CI: 2.429-9.502, P < 0.001) were identified as risk factors for AL. The height of the tumor from the AV ≤ 4 cm (OR = 2.563, 95%CI: 0.986-6.658, P = 0.053) and LCA retention (OR = 0.068, 95%CI: 0.341-0.102, P = 0.105) did not significantly influence AL incidence. The use of DS (OR = 0.564, 95%CI: 0.273-1.167; P = 0.123) also showed no significant efficacy for AL prevention in the univariable analysis.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, AL-related covariates with P < 0.2 (sex, BMI, nCRT, LCA retention, DS, and height of the tumor from the AV), male sex (OR = 2.644, 95%CI: 1.161-6.020, P = 0.021), nCRT (OR = 6.024, 95%CI: 2.830-12.822, P < 0.001), and height of the tumor from the AV ≤ 4 cm (OR = 4.160, 95%CI: 1.488-11.634, P = 0.007) were identified as independent risk factors. Conversely, LCA retention (OR = 0.417, 95%CI: 0.209-0.830, P = 0.013) and DS (OR = 0.204, 95%CI: 0.087-0.481, P < 0.001) were found to be independent protective factors (Table 3).

| Variable | Baseline cohort (n = 505) | SF cohort (n = 84) | ||||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Sex (male vs female) | 2.883 (1.310-6.343) | 0.009 | 2.644 (1.161-6.020) | 0.021 | 2.741 (0.673-11.159) | 0.159 | 2.648 (0.606-11.575) | 0.196 |

| Age (≥ 60 years vs < 60 years) | 0.738 (0.397-1.370) | 0.336 | 0.707 (0.187-2.669) | 0.609 | ||||

| BMI (≥ 25 kg/m2 vs < 25 kg/m2) | 1.899 (1.020-3.536) | 0.043 | 1.716 (0.884-3.330) | 0.111 | 2.450 (0.679-8.841) | 0.171 | 2.678 (0.672-10.678) | 0.163 |

| Diabetes (yes vs no) | 1.544 (0.684-3.485) | 0.296 | 1.580 (0.293-8.509) | 0.594 | ||||

| nCRT (yes vs no) | 4.805 (2.429-9.502) | < 0.001 | 6.024 (2.830-12.822) | < 0.001 | - | - | ||

| LCA retention (yes vs no) | 0.068 (0.341-0.102) | 0.105 | 0.417 (0.209-0.830) | 0.013 | 0.393 (0.028-0.891) | 0.039 | 0.312 (0.021-0.802) | 0.027 |

| Diverting stoma (yes vs no) | 0.564 (0.273-1.167) | 0.123 | 0.204 (0.087-0.481) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Maximal tumor size (> 35 mm vs ≤ 35 mm) | 0.925 (0.498-1.718) | 0.805 | 1.167 (0.311-4.376) | 0.819 | ||||

| TNM stage (III–IV vs I-II) | 1.254 (0.667-2.355) | 0.482 | -- | -- | ||||

| Height of tumor from the anal verge (≤ 4 cm vs > 4 cm) | 2.563 (0.986-6.658) | 0.053 | 4.160 (1.488-11.634) | 0.007 | 1.587 (0.183-13.780) | 0.675 | ||

| Vascular invasion (yes vs no) | 1.433 (0.697-2.947) | 0.328 | 1.253 (0.238-6.594) | 0.790 | ||||

| Nerve invasion (yes vs no) | 1.563 (0.740-3.303) | 0.242 | 2.741 (0.673-11.159) | 0.159 | 2.648 (0.606-11.575) | 0.196 | ||

Further analysis of the SF group revealed that LCA retention was a protective factor for AL in these patients, both in the univariate (OR = 0.393, 95%CI: 0.028-0.891, P = 0.039) and multivariate (OR = 0.312, 95%CI: 0.121-0.802, P = 0.027) analyses (Table 3).

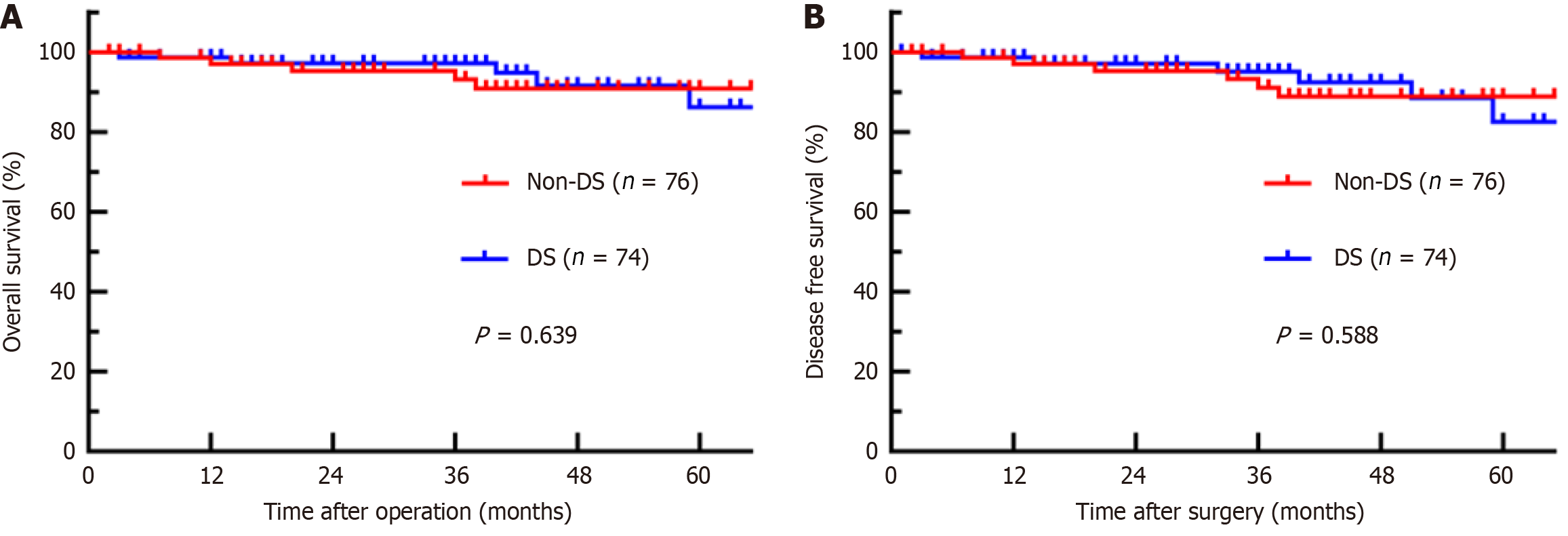

The median follow-up period was 48 months. During this time, 8 patients in the DS group died, with 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates of 98.7%, 97.2%, and 95.1%, respectively, and overall survival (OS) rates of 98.7%, 97.2%, and 97.2%, respectively. In the SF group, 6 patients died, with 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year DFS rates of 97.0%, 95.3%, and 91.1%, respectively, and OS rates of 97.0%, 95.3%, and 95.3%, respectively. The 3-year DFS (P = 0.588) or 3-year OS (P = 0.639) did not significantly differ between the DS and SF groups (Figure 2).

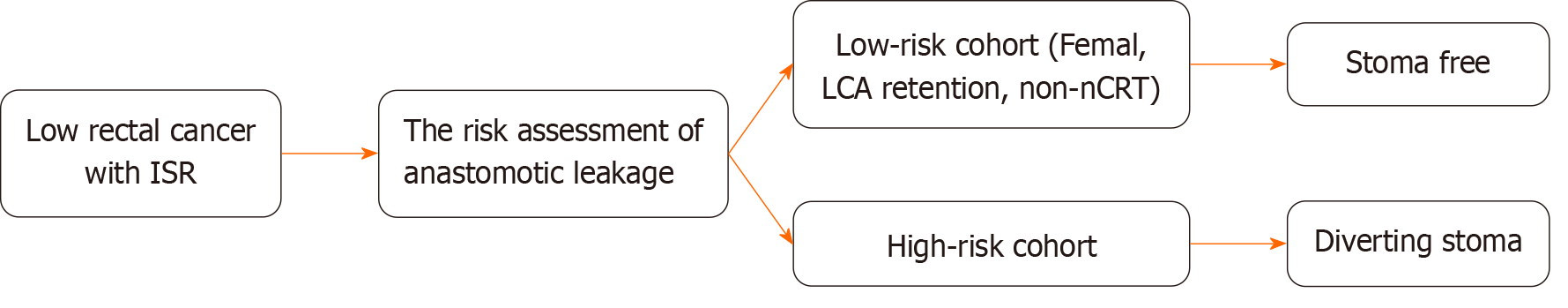

Patients with the following characteristics were defined as a low-risk cohort for AL: Female patients without neoadjuvant therapy and patients with intraoperative preservation of the LCA. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of the high-risk and low-risk cohorts for AL were analyzed (Table 4). The low-risk cohort had an earlier pT stage (P = 0.014), shorter operative time (P = 0.006), and less blood loss (P = 0.003). In terms of postoperative outcomes, this low-risk cohort had a lower risk of postoperative complications than the high-risk cohort (P = 0.021). The AL rate in the low-risk cohort (2 of 97 patients) was significantly lower than the overall incidence of AL in the high-risk cohort (2.1% vs 10.3%, P = 0.010) and the baseline cohort (2.1% vs 8.5%, P = 0.027). Therefore, the clinical decision to perform Ls-ISR without a DS was found to be safe and feasible for this low-risk cohort. A clinical decision analysis chart is recommended for patients undergoing Ls-ISR surgery for low rectal cancer to assess the necessity of a stoma during the procedure (Figure 3).

| Variables | High-risk cohort of AL (n = 408) | Low-risk cohort of AL (n = 97) | P value |

| Tumor size, median (range) mm | 0.212 | ||

| > 35 | 208 (60.0) | 42 (43.3) | |

| ≤ 35 | 200 (40.0) | 55 (56.7) | |

| Differentiation status | 0.625 | ||

| Poor | 61 (15.0) | 12 (12.4) | |

| Well-moderate | 347 (85.0) | 85 (87.6) | |

| pT stage | 0.014 | ||

| 0-2 | 160 (39.2) | 52 (53.6) | |

| 3 | 248 (60.8) | 45 (46.4) | |

| pN stage | 0.267 | ||

| N+ | 149 (36.5) | 29 (29.9) | |

| N0 | 259 (63.5) | 68 (70.1) | |

| M stage | 0.140 | ||

| M1 | 9 (2.2) | 0 (0) | |

| M0 | 399 (97.8) | 97 (100) | |

| pTNM stage | 0.047 | ||

| I-II | 252 (61.8) | 71 (73.2) | |

| III-IV | 156 (38.2) | 26 (26.8) | |

| Tumor height from anal verge, median (range) cm | 0.530 | ||

| ≤ 4.0 | 309 (75.7) | 77 (79.4) | |

| > 4.0 | 99 (24.3) | 20 (20.6) | |

| Operative time, median (range) min | 164 (130-195) | 175 (139-218) | 0.006 |

| Blood loss, median (range) mL | 50 (20-50) | 50 (20-100) | 0.003 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Postoperative complication | 67 (16.4) | 7 (7.2) | 0.021 |

| CD grade I-II | 46 (11.3) | 5 (5.2) | 0.072 |

| CD grade ≥ III | 21 (5.1) | 2 (2.1) | 0.299 |

| AL | 42 (10.3) | 2 (2.1) | 0.010 |

| Grade A-B | 35 (8.6) | 2 (2.1) | 0.027 |

| Grade C | 7 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0.415 |

| Mortality | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0.397 |

| Reoperation | 10 (2.5) | 1 (1.0) | 0.635 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (day) | 9 (4-50) | 10 (4-47) | 0.081 |

| Anastomosis recurrence | 7 (1.7) | 1 (1.0) | 0.974 |

ISR surgery combined with DS is considered the standard procedure for ultralow rectal cancer. DS is routinely performed to minimize the risk of AL and related complications by temporarily diverting bowel contents[10,11]. However, DS may increase the risk of permanent stoma, bowel obstruction, and renal insufficiency due to massive electrolyte loss as well as complications related to stoma closure. Additionally, DS can cause significant mental stress, particularly in Chinese culture, where it can severely impact patients’ social functioning[12-14,20]. Therefore, patients with ultralow rectal cancers who can be exempted from stoma need to be screened out to reduce the negative impacts. To our knowledge, this study was the first to explore the feasibility of Ls-ISR without stoma using the PSM method. In our study, a multivariate analysis of the baseline cohort revealed that male sex, nCRT, and tumor height from the AV ≤ 4 cm were independent risk factors for AL, whereas LCA retention and DS were protective factors. We proposed and clarified that female patients who did not undergo nCRT and the LCA was preserved intraoperatively had an extremely low risk of AL.

The benefits of stoma are balanced by the risk of leakage and stoma-related complications during rectal resection. Therefore, surgeons should focus not only on the consequences of AL but also on the risk of stoma-related complications. Few studies have examined the use of the Ls-ISR to identify candidates who can avoid stomas, primarily because of the high risk of AL and severe complications. A previous meta-analysis of data from four randomized controlled trials revealed a significant reduction in clinically symptomatic leakage (OR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.17-0.59) and fewer repeat opera

In contrast, other investigators have suggested that the routine use of a stoma is not advisable because their studies revealed no reduction in the incidence of leakage[22]. Many potential problems are associated with stoma creation, including reduced quality of life, stoma-related morbidity[23], financial impact, secondary hospitalizations for stoma closure, and the possibility of permanent stoma[24]. Permanent stoma presents a dilemma. Although a DS can reduce the incidence of AL, it can also lead to a permanent stoma if stoma closure fails. The reasons for this failure are varied and include stoma-related complications, tumor factors (such as local recurrence and metastasis), and patient factors (such as physical tolerance to anesthesia and willingness to undergo reoperation). In our study, sphincter preservation in the DS group failed in 47 patients, with anastomotic factors responsible for 22 patients, tumor factors for 19 patients, and patient-related factors for 6 patients. In the SF group, sphincter preservation failed in 2 patients, both due to anastomotic factors.

Finally, our study revealed no significant difference in long-term survival between patients in the low-risk cohort for AL who avoided a DS and those who underwent the procedure. We attribute this finding to the comparable rates of postoperative AL and other serious complications between the two groups, which allowed for the timely completion of adjuvant therapy. Completing adjuvant therapy on schedule is crucial for reducing tumor recurrence and improving OS and DFS. A nationwide investigation by Gadan et al[25], which included 4130 patients with low rectal cancer, revealed that a DS affected only short-term complications and did not impact OS or DFS.

Our study had several limitations. First, this cohort study was retrospective and was conducted by a single surgical team, which may introduce potential bias. The baseline data tended to include a low AL population, and the overall sample size was small. Although propensity score adjustment may have reduced selection bias, residual or confounding factors may persist. In the multivariate analysis, we included variables based on univariate analysis, clinical experience, and previously reported risk factors; however, selection bias was still difficult to avoid. Second, the number of patients with leakage was small, leading to significant differences in the statistical results. Additionally, the proportion of patients who received nCRT was relatively low in our study, raising questions about whether these conclusions apply to patients who have undergone neoadjuvant therapy.

In conclusion, DS could be avoided in female patients without nCRT by preserving the LCA without compromising AL risk or oncological outcomes.

| 1. | Enomoto H, Ito M, Sasaki T, Nishizawa Y, Tsukada Y, Ikeda K, Hasegawa H. Anastomosis-Related Complications After Stapled Anastomosis With Reinforced Sutures in Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Low Rectal Cancer: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:246-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hüser N, Michalski CW, Erkan M, Schuster T, Rosenberg R, Kleeff J, Friess H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of defunctioning stoma in low rectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yamamoto S, Fujita S, Akasu T, Inada R, Takawa M, Moriya Y. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic intersphincteric resection for lower rectal cancer and comparison with open approach. Dig Surg. 2011;28:404-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang B, Zhuo GZ, Zhao K, Zhao Y, Gao DW, Zhu J, Ding JH. Cumulative Incidence and Risk Factors of Permanent Stoma After Intersphincteric Resection for Ultralow Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:66-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Artus A, Tabchouri N, Iskander O, Michot N, Muller O, Giger-Pabst U, Bourlier P, Bourbao-Tournois C, Kraemer-Bucur A, Lecomte T, Salamé E, Ouaissi M. Long term outcome of anastomotic leakage in patients undergoing low anterior resection for rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu J, Zheng L, Ren S, Zuo S, Zhang J, Wan Y, Wang X, Tang J. Nomogram for Predicting the Probability of Permanent Stoma after Laparoscopic Intersphincteric Resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:3218-3229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu JG, Chen HK, Wang X, Tang JQ. [Analysis of risk factors of anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic int ersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer and construction of a no mogram prediction model]. Zhonghua Waike Zazhi. 2021;59:332-337. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tschann P, Weigl MP, Szeverinski P, Lechner D, Brock T, Rauch S, Rossner J, Eiter H, Girotti PNC, Jäger T, Presl J, Emmanuel K, De Vries A, Königsrainer I, Clemens P. Are risk factors for anastomotic leakage influencing long-term oncological outcomes after low anterior resection of locally advanced rectal cancer with neoadjuvant therapy? A single-centre cohort study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:2945-2957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Costantini B, Vargiu V, Santullo F, Rosati A, Bruno M, Gallotta V, Lodoli C, Moroni R, Pacelli F, Scambia G, Fagotti A. Risk Factors for Anastomotic Leakage in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Surgery: A Large Single-Center Experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:4791-4802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Emile SH, Khan SM, Garoufalia Z, Silva-Alvarenga E, Gefen R, Horesh N, Freund MR, Wexner SD. When Is a Diverting Stoma Indicated after Low Anterior Resection? A Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials and Meta-Regression of the Risk Factors of Leakage and Complications in Non-Diverted Patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26:2368-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schlesinger NH, Smith H. The effect of a diverting stoma on morbidity and risk of permanent stoma following anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:1903-1910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cong ZJ, Hu LH, Zhong M, Chen L. Diverting stoma with anterior resection for rectal cancer: does it reduce overall anastomotic leakage and leaks requiring laparotomy? Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:13045-13055. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Emmanuel A, Chohda E, Lapa C, Miles A, Haji A, Ellul J. Defunctioning Stomas Result in Significantly More Short-Term Complications Following Low Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer. World J Surg. 2018;42:3755-3764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ahmad NZ, Abbas MH, Khan SU, Parvaiz A. A meta-analysis of the role of diverting ileostomy after rectal cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:445-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ulrich AB, Seiler C, Rahbari N, Weitz J, Büchler MW. Diverting stoma after low anterior resection: more arguments in favor. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:412-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Anderin K, Gustafsson UO, Thorell A, Nygren J. The effect of diverting stoma on postoperative morbidity after low anterior resection for rectal cancer in patients treated within an ERAS program. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:724-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Anderin K, Gustafsson UO, Thorell A, Nygren J. The effect of diverting stoma on long-term morbidity and risk for permanent stoma after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:788-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A, Holm T, Wong WD, Tiret E, Moriya Y, Laurberg S, den Dulk M, van de Velde C, Büchler MW. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147:339-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 1029] [Article Influence: 68.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 19. | Austin PC. Some methods of propensity-score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and Monte Carlo simulations. Biom J. 2009;51:171-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hol JC, Burghgraef TA, Rutgers MLW, Crolla RMPH, van Geloven AAW, de Jong GM, Hompes R, Leijtens JWA, Polat F, Pronk A, Smits AB, Tuynman JB, Verdaasdonk EGG, Consten ECJ, Sietses C. Impact of a diverting ileostomy in total mesorectal excision with primary anastomosis for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:1916-1932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Seo SI, Yu CS, Kim GS, Lee JL, Yoon YS, Kim CW, Lim SB, Kim JC. The Role of Diverting Stoma After an Ultra-low Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer. Ann Coloproctol. 2013;29:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Enker WE, Merchant N, Cohen AM, Lanouette NM, Swallow C, Guillem J, Paty P, Minsky B, Weyrauch K, Quan SH. Safety and efficacy of low anterior resection for rectal cancer: 681 consecutive cases from a specialty service. Ann Surg. 1999;230:544-52; discussion 552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rullier E, Le Toux N, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, Parneix M, Saric J. Loop ileostomy versus loop colostomy for defunctioning low anastomoses during rectal cancer surgery. World J Surg. 2001;25:274-7; discussion 277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bailey CM, Wheeler JM, Birks M, Farouk R. The incidence and causes of permanent stoma after anterior resection. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:331-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gadan S, Brand JS, Rutegård M, Matthiessen P. Defunctioning stoma and short- and long-term outcomes after low anterior resection for rectal cancer-a nationwide register-based cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:1433-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |