Published online Mar 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i3.102589

Revised: January 6, 2025

Accepted: January 20, 2025

Published online: March 27, 2025

Processing time: 124 Days and 17.2 Hours

Bleeding ectopic varices located in the small bowel (BEV-SB) caused by portal hypertension (PH) are rare and life-threatening clinical scenarios. The current management of BEV-SB is unsatisfactory. This retrospective study analyzed four cases of BEV-SB caused by PH and detailed the management of these cases using enteroscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) and subsequent interventional radio

To analyze the management of BEV-SB caused by PH and develop a treatment algorithm.

This was a single tertiary care center before-after study, including four patients diagnosed with BEV-SB secondary to PH between January 2019 and December 2023 in the Air Force Medical Center. A retrospective review of the medical re

Four out of 519 patients diagnosed with PH were identified as having BEV-SB. The management duration of each phase was 20 person-months, 42 person-months, and 77 person-months, respectively. The four patients received a total of eight and five person-times of EIS and IR treatment, respectively. All patients exhibited recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding following the first EIS, while no further instances of gastrointestinal bleeding were observed after IR treatment. The transfusions administered during each phase were 34, 31, and 3.5 units of red blood cells, and 13 units, 14 units, and 1 unit of plasma, respectively.

EIS may be effective in achieving hemostasis for BEV-SB, but rebleeding is common, and IR aiming to reduce portal pressure gradient may lower the rebleeding rate.

Core Tip: Bleeding ectopic varices located in the small bowel (BEV-SB) caused by portal hypertension is a rare, life-threatening clinical scenario. This retrospective study presented the treatment experience using enteroscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) and subsequent interventional radiology (IR) for BEV-SB. From January 2019 to December 2023, 4 of 519 patients with portal hypertension were identified as having BEV-SB. The management duration of phases from the first episode of BEV-SB to the first EIS, from the first EIS to the first IR, and from the first IR to December 2023 were 20 person-months, 42 person-months, and 77 person-months, respectively. The corresponding transfusions at each phase were 34 units, 31 units, and 3.5 units of red blood cells and 13 units, 14 units, and 1 unit of plasma, respectively. After the comprehensive management, no further gastrointestinal bleeding was observed. We conclude that EIS may be effective in achieving hemostasis in BEV-SB, although rebleeding is common, and IR aiming to reduce portal venous pressure may lower the rebleeding rate.

- Citation: Xiao NJ, Chu JG, Ning SB, Wei BJ, Xia ZB, Han ZY. Successful management of bleeding ectopic small bowel varices secondary to portal hypertension: A retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(3): 102589

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i3/102589.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i3.102589

Ectopic varices (EV) are dilated portal-systemic collaterals that occur outside of the esophagus and stomach, and are usually presented as elevated submucosal tortuous vessels. Bleeding EV (BEV) can manifest as active bleeding or as clots, erosive spots, or ulcers without active bleeding. Small bowel varices, accounting for 0.6%-17% of all EV[1,2], are primarily caused by portal hypertension (PH) and can result in life-threatening hemorrhage with a mortality rate of up to 40%[2-4]. Despite numerous reported treatment strategies, outcomes for BEV in the small bowel (BEV-SB) have often been unsatisfactory[5]. Moreover, the scarcity of data on effective therapeutic modalities for BEV-SB hinders the conduct of large randomized controlled trials and precludes the identification of the ideal management approach for this rare condition[6]. In this before-after study, we retrospectively analyzed four patients who underwent both enteroscopic injection scle

We reviewed patients diagnosed with PH and BEV-SB at the Air Force Medical Centre between January 2019 and December 2023. Medical records and imaging data from the hospital information system and picture archiving and communication system were retrospectively collected for demographics, hemoglobin (Hb) concentration, transfusions, endoscopic treatment, and IR treatment. The management of these patients involved the utilization of EIS followed by IR, therefore a before-after study was designed. The management duration of BEV-SB in each patient was retrospectively divided into three phases based on these two approaches: (1) Phase 1, from the initial occurrence of BEV-SB to the initial EIS; (2) Phase 2, from the initial EIS to the initial IR treatment; and (3) Phase 3, from the initial IR to December 2023. Descriptive statistics were performed to clarify the blood transfusions in each phase. The local institutional review board approved the retrospective study (No. 2023-151-S01), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Four out of the 519 patients diagnosed with PH were identified as having BEV-SB. The median age of these 4 patients at the first episode of BEV-SB was 47.5 years (range: 37 years to 58 years), with a 2:2 female-to-male ratio. In 3 patients, PH was caused by cirrhosis due to a history of hepatitis B, drug-induced liver injury, and alcoholic hepatitis, respectively. The fourth patient was diagnosed with regional PH resulting from splenic vein stenosis following acute pancreatitis. BEV-SB presented mainly as melena in two patients, one of whom concurrently experienced hematochezia during follow-up, and as hematochezia in the other two patients. The average Hb concentration at the first hospitalization was 72 g/L (range: 49 g/L to 85 g/L) and the Child-Pugh scores were 5, 6, 7, and 5, respectively.

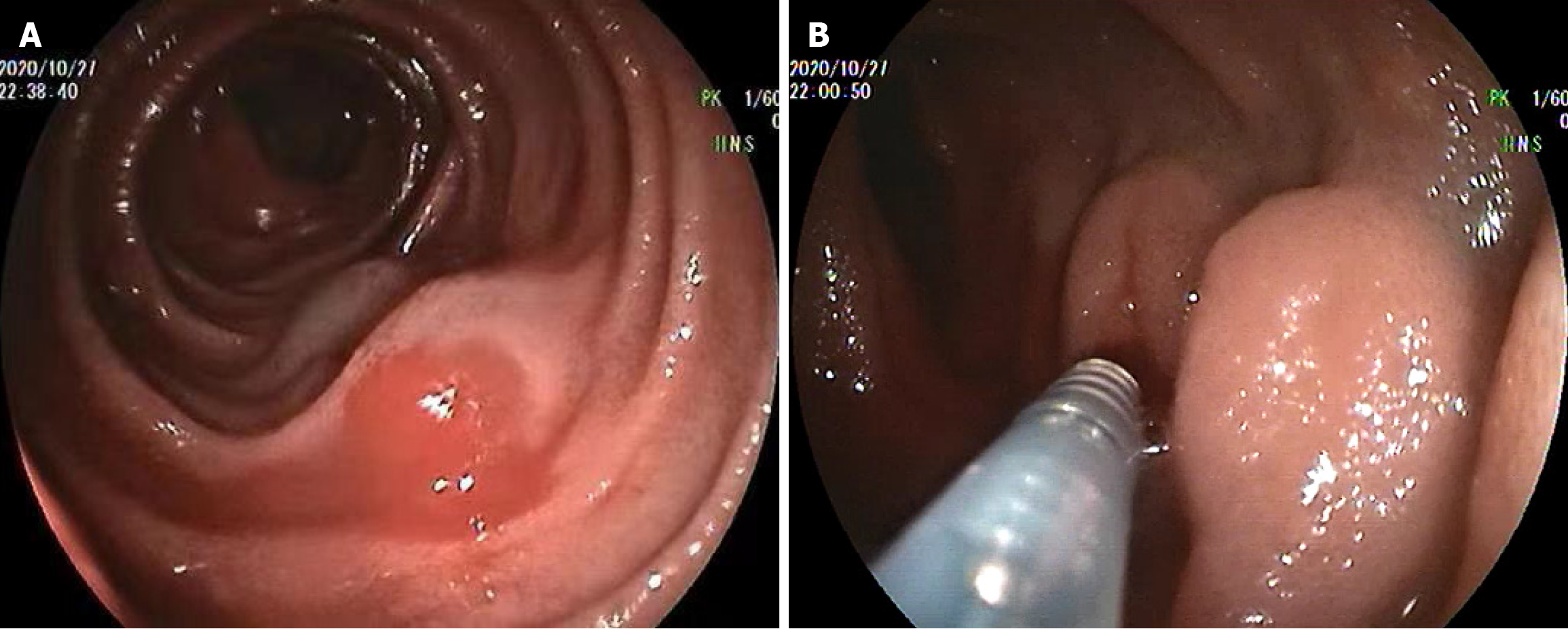

The four patients were hospitalized 23 times during a total of 139 person-months of follow-up and received 68.5 units of red blood cells and 28 units of plasma transfusions. The duration and transfusions required for each phase for each patient are shown in Table 1. During phase 1, 17 conventional endoscopies (9 gastroscopies and 8 colonoscopies) were performed in the four patients, but no bleeding lesions were identified. However, all patients had esophageal varices. Although three patients underwent prophylactic endoscopic esophageal variceal ligation, the bleeding continued. For further investigation, three patients underwent enteroscopy, while one patient underwent capsule endoscopy, which indicated suspected BEV-SB, and subsequently underwent enteroscopy. During enteroscopy, BEV were located in the jejunum, 80 cm and 150 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz, and in the ileum, 40 cm and 100 cm distal to the ileocecal valve, respectively. The length of the varices ranged from approximately 6 cm to 15 cm with oozing or erosive lesions. After verifying the BEV-SB, we executed the first EIS for each patient (Figure 1), achieving temporary hemostasis in all patients.

| Patients | Phase 1 (first episode of BEV-SB to first EIS) | Phase 2 (first EIS to first IR) | Phase 3 (first IR to the December 2023) | |||

| Transfusions, RBC/P (units) | Duration, (months) | Transfusions, RBC/P (units) | Duration, (months) | Transfusions, RBC/P (units) | Duration, (months) | |

| 1 | 16/6 | 11 | 9.5/3 | 32 | 0/0 | 13 |

| 2 | 6/4 | 1 | 9/6 | 4 | 0/0 | 39 |

| 3 | 8/3 | 1 | 10.5/5 | 1 | 3.5/1 | 12 |

| 4 | 4/0 | 7 | 2/0 | 5 | 0/0 | 13 |

| Total | 34/13 | 20 | 31/14 | 42 | 3.5/1 | 77 |

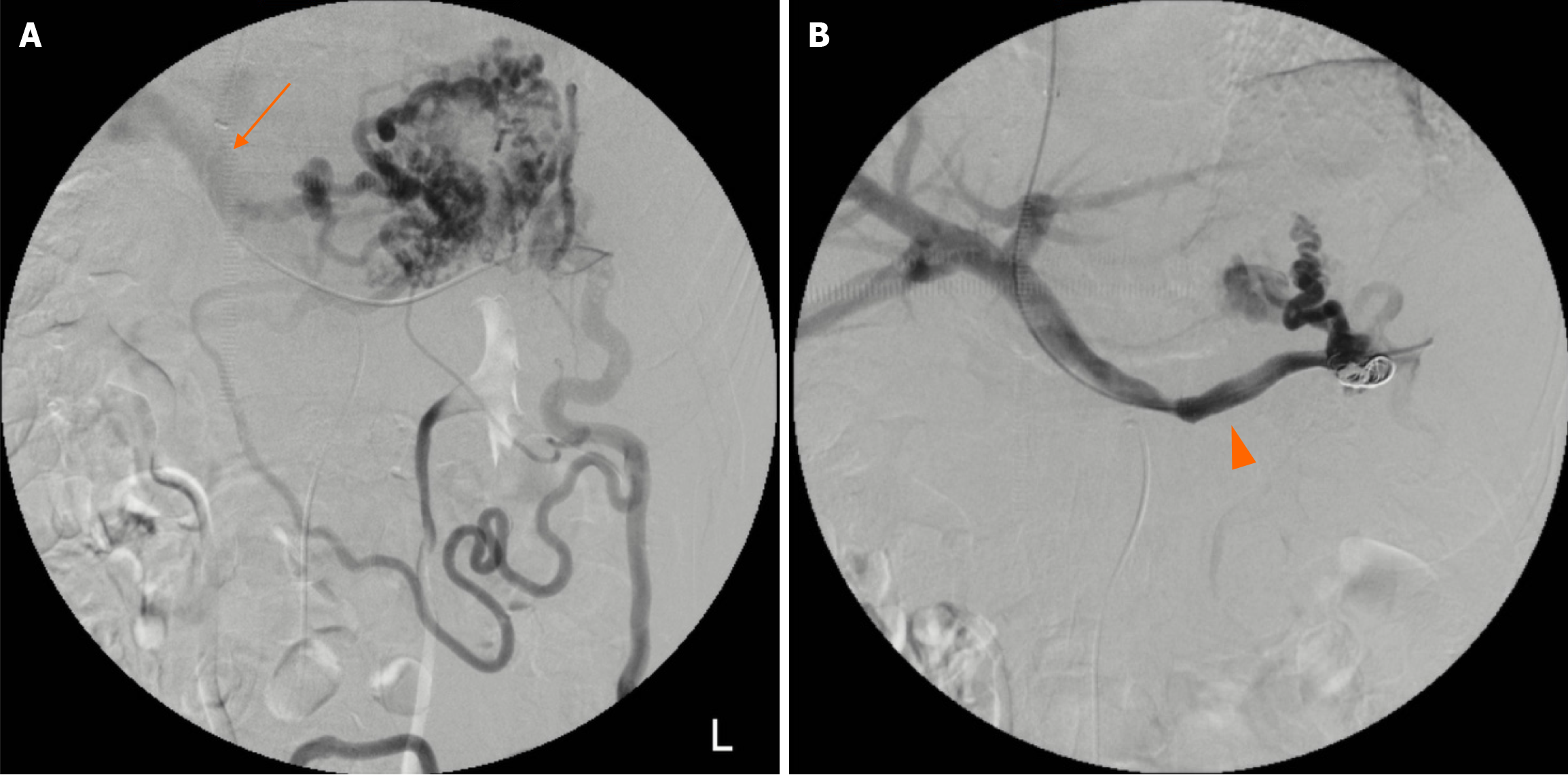

However, the rebleeding occurred in 19 months, 4 months, 1 month, and 5 months after the first EIS, respectively. Patient 1 underwent two additional EIS, at 19 months and 32 months after the first EIS due to concurrent melena and hematochezia, and then accepted the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Patients 2 and 3 directly underwent TIPS after achieving cessation of rebleeding with the second EIS. Patient 4 underwent splenic vein stent implantation (Figure 2) through the transjugular approach due to recurrent melena after the first EIS.

TIPS was performed on 3 cirrhotic patients with balloon dilation and metal stent implantation. The PPG was 30.5 mmHg, 37.5 mmHg, and 27.6 mmHg before TIPS, which decreased to 9.6 mmHg, 8.8 mmHg, and 10.3 mmHg after the procedure, respectively. However, patient 3 suffered rebleeding on the second day after TIPS, and an urgent IR was attempted, revealing acute shunt thrombosis. Another mental stent was then implanted, maintaining the PPG at 11.0 mmHg. In patient 4, the distal and proximal splenic vein pressures were 16.2 mmHg and 11.0 mmHg, respectively. Metal stents were implanted into the stenosis splenic vein, restoring pressure to 11.8 mmHg and 11.4 mmHg, respectively. During phase 3, there were 7 additional hospitalizations due to periodic follow-up visits, but no further gastrointestinal bleeding or other obvious complications were observed. At the last follow-up, the average Hb was 104.7 g/L (range: 86 g/L to 128 g/L).

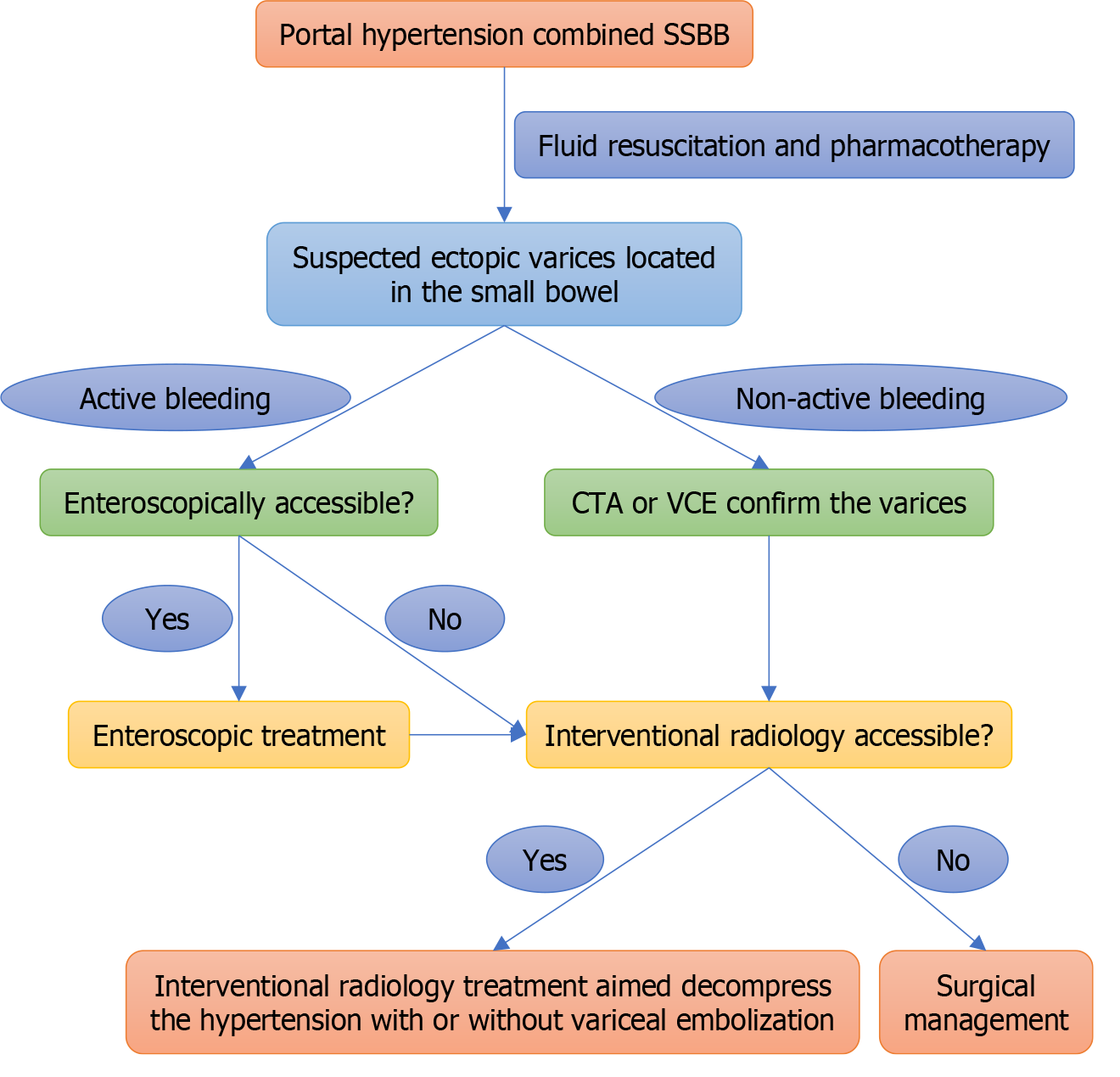

Overt gastrointestinal bleeding is a common emergency that poses a significant challenge for clinicians. When conventional endoscopies like gastroscopy and colonoscopy fail to detect any bleeding lesions, the condition is known as “suspected small bowel bleeding” (SSBB). While BEV-SB is a rare cause of SSBB, advancements in diagnostic algorithms, enteroscopy, and capsule endoscopy have improved the diagnosis of this condition[7]. However, the treatment of BEV-SB remains a debated topic, with several strategies proposed, mainly including endoscopy, IR, and surgery. Unfortunately, an unsatisfactory prognosis is frequently encountered with this complex condition[5]. Moreover, due to the rarity of this disease and limited available data, determining the ideal management strategy for BEV-SB remains challenging.

Enteroscopy is considered a primary treatment for SSBB in selected patients given its potential therapeutic efficacy, ease of use, and tolerability[7]. EIS has been reported to be effective in managing BEV[8] and may have similar efficacy compared to enteroscopic cyanoacrylate injection[9]. Since enteroscopic band ligation is not available in our institution, we performed EIS with lauromacrogol injection (Polidocanol) as the first line therapy based on the endoscopist’s clinical experiences. However, despite the efficient temporary hemostasis, as observed in our retrospective study, rebleeding of BEV-SB in the setting of PH can occur in 1-19 months in all patients after the first EIS. This is consistent with a singlecenter study where 86.7% of patients (13/15) achieved initial hemostasis by endoscopic treatment, but 53.3% (8/15) presented rebleeding[2]. Therefore, while EIS may serve as an option to control bleeding in the initial therapy, advanced treatment is required for BEV-SB with PH.

Reducing PPG through the IR approach is effective in managing BEV-SB. TIPS, which is designed for the decompression of PH, is associated with a relatively lower rebleeding rate[10], has been widely applied in patients with cirrhosis, and has also been recommended by guidelines[11,12]. For patients with prehepatic PH (non-cirrhosis) caused by stenosis or thrombosis of portal collaterals, recanalization may be the primary decompressive strategy if it is technically feasible[3]. Other IR approaches, such as percutaneous antegrade transhepatic venous obliteration or balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, have also been used to treat BEV. In a case series of 12 patients treated by percutaneous antegrade transhepatic venous obliteration, the rebleeding rate is 50%[13]. In another case series of 6 patients treated by balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, the rebleeding rate is 16.6%[14]. Additionally, as those obliteration therapies, in contrast to TIPS or recanalization, do not decrease the PPG, they can even worsen esophageal varices and ascites. Therefore, for patients with BEV-SB caused by PH, as shown in our study, IR with or without obliteration aimed at decompressing the PH is the first choice to reduce the risk of rebleeding.

In some emergencies, enteroscopic treatment may be the first choice in BEV-SB with active bleeding because of its relatively high immediate hemostasis rate and ease of performance. However, in patients who have been assessed as inaccessible for enteroscopy or in situations where enteroscopic treatment is not available, IR may be considered. In our experience, most patients can achieve temporary hemostasis with pharmacotherapy alone, making IR a selective pro

In our retrospective study, we did not notice any overt hepatic encephalopathy requiring medical intervention, although it is the major potential complication of TIPS affecting almost one-third of patients. This difference may be due to a small sample bias. Furthermore, our solid follow-up strategy and post-TIPS education may also benefit to prevent hepatic encephalopathy. There was a case with post-TIPS urgent rebleeding associated with acute thrombosis of the shunt, which is an uncommon complication with a rate of fewer than 5%. Immediate restoration of patency of the stent-shunt is the pertinent management, and polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent may help prevent this complication[15]. Since then, no overt gastrointestinal rebleeding has been observed in any of the patients in 1-3 years’ follow-up, and this may be attributed to our appropriate PPG maintenance with periodic TIPS revision. Moreover, for the prehepatic PH, we achieved the “anatomical” decompression by recanalization with splenic vein stent implantation, which proved highly effective with the follow-up.

The limitations of the study, including the small sample size and single-center design, emphasize the need for larger, multi-center studies to confirm the effectiveness of the management strategies discussed in this study. Additionally, we do not consider surgical treatment as an alternative management in our center, for we have no experience in surgical treatment of BEV-SB. However, surgical treatments such as liver transplantation, surgical shunt, or splenectomy and devascularization procedures have been successfully performed in carefully selected patients, and have achieved hemostasis and blood flow reconstruction in rare situations when enteroscopic treatment and IR measures have failed[16]. Although surgical treatment can be effective in controlling variceal bleeding, it is highly invasive, and surgery for PH should be performed by experienced surgeons because of its complex and variable operative requirements. Com

In conclusion, EIS may serve as a bleeding control option in the initial treatment of BEV-SB. IR such as TIPS aimed at reducing PPG or recanalization of portal venous collaterals may be beneficial in reducing the rebleeding rate.

| 1. | Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yipeng W, Anjiang W, Bimin L, Chenkai H, Size W, Xuan Z. Clinical characteristics and efficacy of endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal ectopic varices: A single-center study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:35-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Saad WE, Lippert A, Saad NE, Caldwell S. Ectopic varices: anatomical classification, hemodynamic classification, and hemodynamic-based management. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:158-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Helmy A, Al Kahtani K, Al Fadda M. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jansson-Knodell CL, Calderon G, Weber R, Ghabril M. Small Intestine Varices in Cirrhosis at a High-Volume Liver Transplant Center: A Retrospective Database Study and Literature Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1426-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tranah TH, Nayagam JS, Gregory S, Hughes S, Patch D, Tripathi D, Shawcross DL, Joshi D. Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:1046-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pennazio M, Rondonotti E, Despott EJ, Dray X, Keuchel M, Moreels T, Sanders DS, Spada C, Carretero C, Cortegoso Valdivia P, Elli L, Fuccio L, Gonzalez Suarez B, Koulaouzidis A, Kunovsky L, McNamara D, Neumann H, Perez-Cuadrado-Martinez E, Perez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Piccirelli S, Rosa B, Saurin JC, Sidhu R, Tacheci I, Vlachou E, Triantafyllou K. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy. 2023;55:58-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 74.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hori A, Watanabe Y, Takahashi K, Tonouchi T, Kimura N, Setsu T, Ikarashi S, Kamimura H, Yokoyama J, Terai S. A rare case of duodenal variceal bleeding due to extrahepatic portal vein obstruction successfully treated with endoscopic injection sclerotherapy. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2022;15:617-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Al-Khazraji A, Curry MP. The current knowledge about the therapeutic use of endoscopic sclerotherapy and endoscopic tissue adhesives in variceal bleeding. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:893-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vidal V, Joly L, Perreault P, Bouchard L, Lafortune M, Pomier-Layrargues G. Usefulness of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of bleeding ectopic varices in cirrhotic patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:216-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1431] [Article Influence: 178.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 12. | Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, Travis S, Armstrong MJ, Tsochatzis EA, Rowe IA, Roslund N, Ireland H, Lomax M, Leithead JA, Mehrzad H, Aspinall RJ, McDonagh J, Patch D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Gut. 2020;69:1173-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nadeem IM, Badar Z, Giglio V, Stella SF, Markose G, Nair S. Embolization of parastomal and small bowel ectopic varices utilizing a transhepatic antegrade approach: A case series. Acta Radiol Open. 2022;11:20584601221112618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hashimoto N, Akahoshi T, Yoshida D, Kinjo N, Konishi K, Uehara H, Nagao Y, Kawanaka H, Tomikawa M, Maehara Y. The efficacy of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration on small intestinal variceal bleeding. Surgery. 2010;148:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Suhocki PV, Lungren MP, Kapoor B, Kim CY. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt complications: prevention and management. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015;32:123-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Symeonidis D, Koukoulis G, Christodoulidis G, Mamaloudis I, Chatzinikolaou I, Tepetes K. Mesocaval shunt for portal hypertensive small bowel bleeding documented with intraoperative enteroscopy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:424-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |