Published online Jan 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i1.99758

Revised: October 7, 2024

Accepted: October 31, 2024

Published online: January 27, 2025

Processing time: 150 Days and 8.9 Hours

T/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) is a highly aggressive subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma characterized histologically by the presence of a few neoplastic large B cells amidst an abundant background of reactive T lymphocytes and/or histiocytes. T/HRBCL commonly affects the lymph nodes, followed by extranodal sites, such as the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, with rare occurrences in the gastrointestinal tract. Primary gastroin

A 63-year-old man was hospitalized with a one-month history of jaundice and weight loss of approximately 3 kg. Laboratory tests revealed increased hepatic parameters in a cholestatic pattern and elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels. An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed a low-density mass within the descending duodenum and dilation of the bile and pancreatic ducts. He was clinically diagnosed with a duodenal tumor. During surgery, a 7.0 cm × 8.0 cm mass was identified within the descending duodenum, so pancreaticoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy were performed. Following operative biopsy, the tumor was diagnosed as primary duodenal T/HRBCL. The patient refused postoperative chemotherapy and died four months after surgery.

Primary duodenal T/HRBCL is an extremely rare and highly aggressive malignancy. The initial treatment strategies should be based on the original site of the tumor, the disease stage, and the patient's physical condition. Chemotherapy-based comprehensive treatment is still the main treatment method for primary gastrointestinal T/HRBCL.

Core Tip: Primary duodenal T/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) is an extremely rare and highly aggressive malignancy. It lacks specific clinical and endoscopic manifestations, and it is difficult to differentiate from inflammatory diseases, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, and other diseases on a histological basis, thereby hindering early diagnosis. The initial treatment strategies should be based on the original site of the tumor, the disease stage, and the patient's physical condition. Chemotherapy-based comprehensive treatment is still the main treatment method for primary gastrointestinal T/HRBCL. We report a case of primary duodenal T/HRBCL complicated with obstructive jaundice to improve the clinician’s understanding.

- Citation: Chen XY, Yang JY, Chen YH, Liu AN, Wu SS, Ji Zhi SN, Zheng SM. Primary duodenal T/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma complicated with obstructive jaundice: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(1): 99758

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i1/99758.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i1.99758

Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma arises from the submucosal lymphatic tissue of the gastrointestinal tract and accounts for 1% to 8% of all gastrointestinal malignancies and 30% to 40% of extranodal lymphomas[1-3]. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma predominantly affects the stomach (55.3% to 75.0%), followed by the small intestine (14.3% to 30.0%) and large intestine (5.0% to 19.7%)[2,3]. Primary duodenal lymphoma (PDL) comprises 12% of all duodenal malignancies and 6% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas[3,4]. PDL is relatively uncommon, with nonspecific clinical and endoscopic presentations, making it difficult to differentiate from inflammatory and other neoplastic intestinal diseases (e.g., adenocarcinoma).

PDL has diverse histological types, with follicular lymphoma being the most common subtype (41.1% to 61.9%), followed by diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (14.3% to 32.8%), mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (14.3%), mantle cell lymphoma (2.7%), T-cell lymphoma (2.6% to 4.8%), and other rare subtypes, such as Burkitt lymphoma and T/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL)[1]. T/HRBCL, a rare and highly aggressive subtype of DLBCL, accounts for approximately 1% to 3% of all large B-cell lymphomas[5]. It primarily affects the lymph nodes, with only 5% originating extranodally, commonly in the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and lungs[6]. A review of the literature revealed that only 9 cases of gastrointestinal T/HRBCL have been reported (Table 1), with duodenal T/HRBCL being exceptionally rare. We present a case of duodenal T/HRBCL complicated by obstructive jaundice.

| Ref. | Age/sex | Site | Lesion type | Biopsy method | Stage | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Tóth et al[7], 1997 | 77/F | Gastric antrum | Ulcerative | Surgery | IE | Partial gastrectomy | 18 months/survived |

| Barut et al[8], 2016 | 76/F | Stomach | Mixed | Surgery | NA | Surgery + chemotherapy | NR |

| Zehani et al[9], 2017 | 41/M | Stomach | Ulcerative | Surgery | NA | Total gastrectomy | 4 days/died |

| Tan et al[10], 2018 | NR/M | Gastric corpus | Ulcerative | Surgery | IE | Partial gastrectomy + CHOP | 2 years/survived |

| Sogunro et al[11], 2020 | 55/M | Gastric fundus | Ulcerative | Surgery | IV | Splenectomy + gastric fundus resection + distal pancreatectomy + R-CHOP | NR |

| Udhreja et al[12], 2009 | 55/F | Cecum, ascending colon | Mixed | Surgery | II | Resection of cecum and ascending colon | NR |

| Agrawal et al[13], 2020 | 41/M | Ascending colon | Ulcerative | Surgery | II | Right hemicolectomy + R-CHOP | NR |

| Li et al[14], 2019 | 48/M | Ileum | Elevated | Surgery | IIE | Right hemicolectomy | NR |

| Köksal et al[15], 2013 | 28/M | Duodenum | Mixed | Endoscopy | IE | R-CHOP | 1 year/survived |

A 63-year-old male with a one-month history of skin and scleral jaundice was admitted to our hospital.

The patient presented with skin and scleral jaundice accompanied by decreased appetite, aversion to oil, abdominal distension, and 3 kg weight loss over one month.

The patient reported no remarkable history of past illness.

The patient had no related personal or family history.

Physical examination revealed generalized skin and scleral jaundice. No superficial lymphadenopathy was palpable. The abdomen was flat and soft. No palpable mass or hepatosplenomegaly was observed.

Laboratory tests revealed elevated hepatic parameters in the cholestatic pattern, with a total bilirubin of 199.4 μmol/L, direct bilirubin of 123.9 μmol/L, indirect bilirubin of 75.5 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase of 173 IU/L, total bile acid of 97.6 μmol/L, γ-glutamyl transferase of 622.1 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase of 468 IU/L, and aspartate aminotransferase of 91.6 IU/L. Blood cell analysis revealed a decreased hemoglobin concentration of 115 g/L. The patient was positive for urine bilirubin and fecal occult blood. The carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and CA125 Levels were 67.50 U/mL and 36.30 U/mL, respectively. The results for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus, syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus infection were all negative.

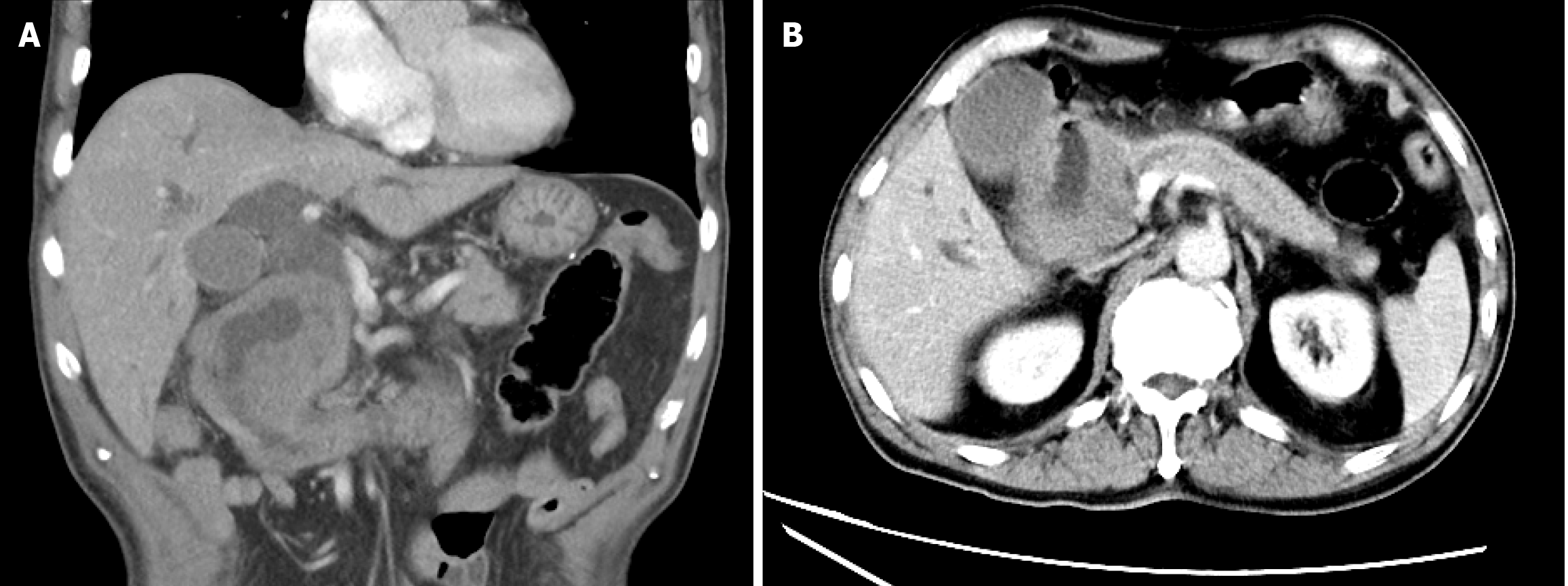

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed heterogeneous thickening of the descending duodenum with a 7.6 cm × 7.4 cm × 7.4 cm low-density mass, mild heterogeneous enhancement after contrast, luminal narrowing, blurred perienteric fat planes (Figure 1A), and dilation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts and the pancreatic duct (Figure 1B).

Based on the clinical, imaging, histological, and immunophenotypic features, the patient was finally diagnosed with primary duodenal T/HRBCL.

According to the clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings, a preliminary diagnosis of a duodenal tumor with obstructive jaundice was made. As the gradual deterioration of the patient's condition, manifested as abdominal distension, vomiting, occult blood in feces, and a decrease in hemoglobin levels, the possibility of duodenal obstruction and gastrointestinal bleeding were considered. Laparotomy revealed an approximately 7.0 cm × 8.0 cm mass within the descending duodenum, involving the distal common bile duct and pancreatic head, with biliary stasis in the liver and an extrahepatic bile duct diameter of approximately 1.5 cm. Based on these intraoperative observations, a duodenal tumor was considered. Therefore, pancreaticoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy were performed to relieve biliary obstruction.

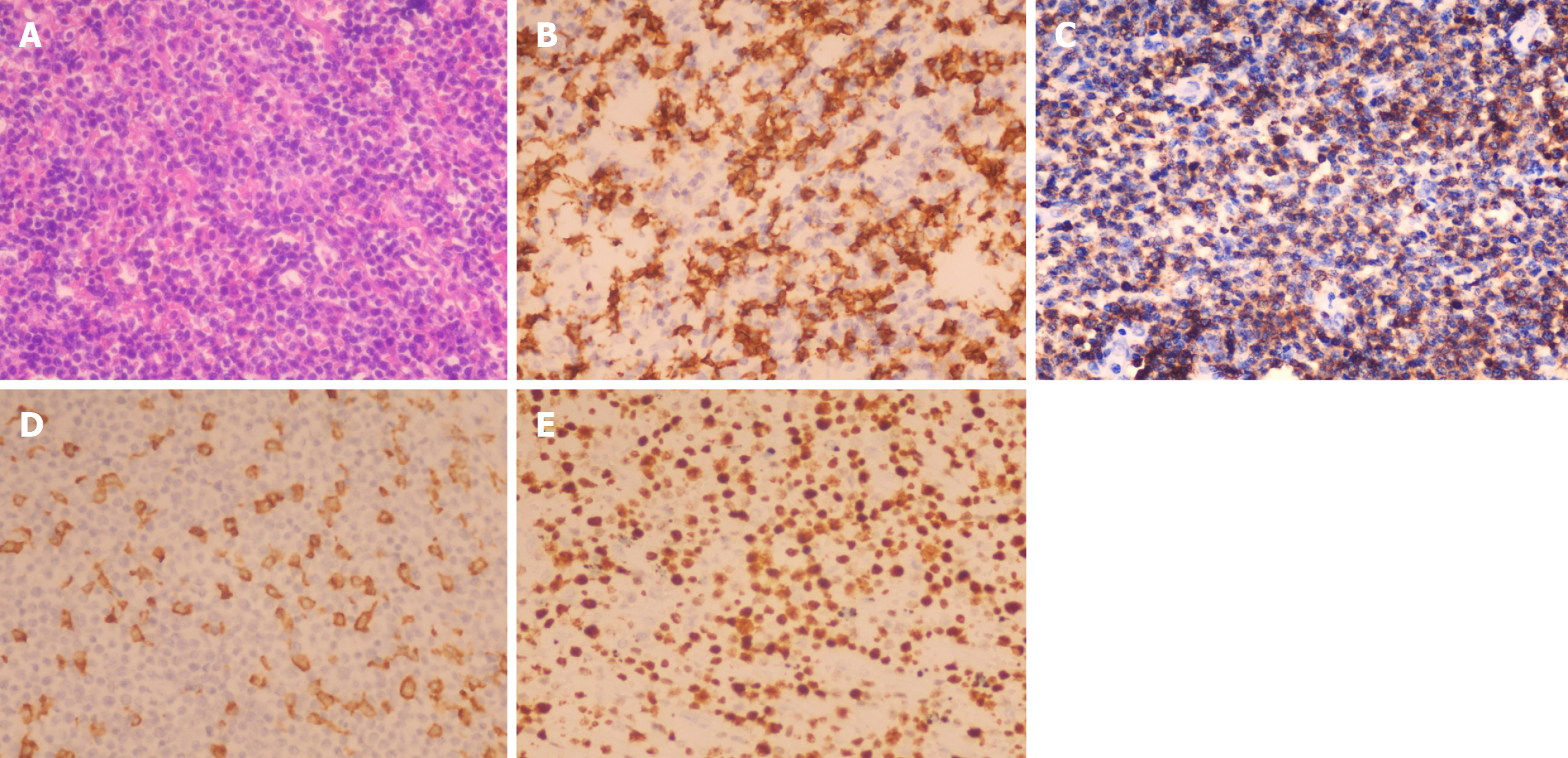

Postoperative histology of the duodenal biopsy revealed tumor infiltration throughout the duodenal wall, extending to the pancreatic head and common bile duct wall. The normal duodenal wall architecture was effaced, with scattered large, atypical cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli infiltrating a background of numerous small lymphocytes and fewer histiocytes (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry revealed scattered large tumor cells positive for the B-cell markers CD20 (Figure 2B) and PAX-5. Most of the small lymphoid cells were CD3-positive T cells (Figure 2C). The histiocytes expressed CD163 (Figure 2D). Immunostaining for Ki-67 revealed a proliferation fraction of 60% among large atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 2E). In situ hybridization was negative for EBER. Gene rearrangement testing did not detect IGH, IGK, or IGL gene rearrangements.

Postoperatively, the patient's jaundice improved. Repeated liver function tests revealed a total bilirubin level of 95.2 μmol/L, direct bilirubin level of 65.3 μmol/L, indirect bilirubin level of 30 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase level of 32.2 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase level of 32 IU/L, and γ-glutamyl transferase level of 274.4 IU/L. Unfortunately, due to financial constraints, the patient did not undergo pertinent laboratory tests for lymphoma and refused postoperative chemotherapy. Following a telephone follow-up, he died four months after surgery due to lymphoma recurrence accompanied by liver infiltration and liver failure.

To investigate the clinical features and diagnostic and treatment advancements in primary duodenal T/HRBCL, we reviewed previous studies on this disease (Table 1). Among the 9 gastrointestinal T/HRBCL cases, the primary sites were the stomach (5 cases)[7-11], colon (2 cases)[12,13], and ileum (1 case)[14], with only one case in the duodenum[15]. The common clinical symptoms are abdominal pain, distension, an abdominal mass, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, fever of unknown origin, and fatigue. The main complications were gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, peritonitis, abdominal abscess, and septic shock, suggesting an aggressive disease course.

On CT, PDLs typically present as asymmetric or eccentric thickening and heterogeneous enhancement of the intestinal wall, with luminal narrowing, proximal luminal dilation, and blurred perienteric fat space. With disease progression, mesenteric vessels, the pancreas, the liver, and distant lymph nodes may get involved. If the PDL presents as a mass lesion, it can compress the pancreaticobiliary ducts, causing dilation of these ducts, gallbladder enlargement, and pancreatic head swelling[4,16,17]. Primary gastrointestinal T/HRBCL should be differentiated from inflammatory diseases, such as active Crohn's disease (CD), which can exhibit a "target sign" or "double halo sign" on contrast-enhanced CT, along with mesenteric vascular hyperplasia, expansion, and mesenteric fat creeping signs.

The endoscopic or intraoperative gross manifestations of gastrointestinal T/HRBCL are diverse. The lesions of gastrointestinal T/HRBCL mainly include ulcerative, protuberant, and ulcerative protuberant (mixed) types (Table 1), which are similar to the endoscopic manifestations of gastrointestinal DLBCL. Among them, the ulcerative type is more common in gastrointestinal T/HRBCL, presenting as single or multiple irregular superficial or deep ulcers with mucus exudation, necrosis, dirty coating on the surface, and raised edges, accompanied by changes such as intestinal lumen stenosis and intestinal wall stiffness[7,10,11,15]. Endoscopically, different cytological subtypes have relatively characteristic changes. For example, multiple white granular lesions are the main feature of follicular lymphoma, while nodular lesions are common in MALT lymphoma, and multiple polypoid elevations are relatively typical for mantle cell lymphoma. Ulcerative and protuberant lesions are more common in DLBCL. These relatively characteristic manifestations often play a certain role in clinical diagnosis[1]. Early PDLs may manifest as mucosal hyperemia or erosion under endoscopy, which is not easy to distinguish from inflammatory diseases such as CD. The relatively characteristic manifestations of CD under endoscopy, such as aphthous ulcers, discontinuous and asymmetric fissure ulcers, and a paving-stone-like appearance, are helpful for differentiation. Gastrointestinal lymphomas mostly originate from submucosal lymphoid tissue, and endoscopic biopsy sampling is often limited, resulting in a low early diagnosis rate[18,19]. Among the 9 previously reported cases of primary gastrointestinal T/HRBCL (Table 1), most patients had stage I or II disease. Although 7 patients underwent endoscopic biopsy, only 1 patient was definitively diagnosed, and the remaining 8 patients were diagnosed through surgical biopsy. Therefore, when diagnoses are not made after repeated endoscopic biopsy, but there is a high suspicion of malignant tumors in clinical practice, timely laparotomy can be performed for definitive diagnosis and treatment of related complications. In recent years, the development of endoscopic technology has facilitated the early diagnosis of gastrointestinal malignancies. The manifestations of primary gastrointestinal lymphoma under magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI) are reduced vascular networks and irregular vessels. Biopsies guided by ME-NBI are expected to improve the diagnostic rate of early gastrointestinal lymphoma[20,21]. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) can reveal the hierarchical structure of the gastrointestinal wall and surrounding lymph node lesions. Under EUS, gastrointestinal lymphoma may manifest as local or extensive hypoechoic thickening of the gastrointestinal wall, blurred, or absent intestinal wall boundaries, and lesions that may invade adjacent structures by breaking through the serosa, which helps assess the depth of lesion invasion and staging. The positive rate of EUS-guided biopsy for primary gastrointestinal lymphoma is 89.38%, and the accuracy rate of invasion depth is 76%[22,23].

T/HRBCL has a wide range of cytological spectra, and its histological characteristics include the presence of fewer than 10% large pleomorphic neoplastic B cells (CD20-, CD79a-, or PAX-5-positive) scattered or clustered in an inflammatory background of many activated small T lymphocytes (CD3-, CD4-, CD43- or CD45RO-positive) with or without nonepithelioid histiocytes (CD68- or CD163-positive)[5]. T/HRBCL has the histological features of a few tumor cells and a significant inflammatory cell response; thus, intestinal T/HRBCL needs to be distinguished from inflammatory diseases, such as CD and tuberculosis. The pathological histology of CD commonly shows characteristic changes, such as crypt structural abnormalities, fissure-like ulcers, and noncaseating granulomas. The infiltrating cell components in CD are mainly neutrophils, lymphocytes, and other acute and chronic inflammatory cells without atypical lymphocytes. In addition, T/HRBCL should also be distinguished from nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) because of their overlapping morphology and immunophenotype, similar gene expression profiles of tumor cells, and the possibility of NLPHL patients transforming into T/HRBCL[24]. The histological background of T/HRBCL is dominated by small T cells or histiocytes, which often lack follicular dendritic cell (FDC) networks and rarely have reactive B lymphocytes[5,24]. In contrast, NLPHL is characterized by FDC network structures with scattered large tumor cells, known as "popcorn" cells, with a background dominated by nonneoplastic small B lymphocytes and well-formed T-cell (CD57-, PD-1-, CD3-, or CD4-positive) rosettes[24].

The current treatment for gastrointestinal T/HRBCL is based mainly on chemotherapy or combined surgery. Chemotherapy regimens for T/HRBCL generally use treatment protocols that match the staging of DLBCL. Previously, the CHOP scheme (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) was recommended as the basic chemotherapy for T/HRBCL patients, with a complete response (CR) rate of 52% to 63% for T/HRBCL, a 3-year overall survival (OS) rate of 46% to 88%, and a 5-year OS rate of 20% to 58%[25,26]. With the widespread use of rituximab (R), the CR rate of R-CHOP for T/HRBCL patients is 91%[26]. The intensified R-CHOP/R-ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) regimen (4 cycles of R-CHOP followed by 3 cycles of R-ICE) has better CR (95% vs 70%) and 3-year OS (100% vs 79%) than the R-CHOP or R-EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin) regimens for T/HRBCL[27]. In addition, the 2024 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend R-EPOCH as a first-line treatment for patients with mesenteric disease in stage II or III-IV large B-cell lymphoma. Although they achieve CR with chemotherapy, 39% of T/HRBCL patients experience recurrence, and another 15% to 41% of patients do not respond to chemotherapy, making them relapsed/refractory (r/r) patients. The use of salvage second-line regimens such as ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin), R-ICE, R-DHAP (dexamethasone, cisplatin, and cytarabine), or R-Gemox (gemcitabine and oxaliplatin) for r/r-T/HRBCL patients has an overall response rate of 71% to 75% and a CR rate of 57%[28,29].

The results of studies on surgical treatment for gastrointestinal lymphoma are inconsistent, which may be related to factors such as histocytological classification, disease stage, and complications of lymphoma. A retrospective study by Kim et al[30] included 345 patients with intestinal DLBCL[30]. For stage I-II patients, the CR and 3-year OS rates of the 163 patients in the surgery combined with chemotherapy group were greater than those of the 87 patients in the chemotherapy-only group (CR: 85.3% vs 64.4%, OS: 91% vs 62%), with a lower recurrence rate (15.3% vs 36.8%)[30]. For 77 patients with stage IV disease, the CR and 3-year OS of the 25 patients in the surgery combined with chemotherapy group were not superior to those of the 52 patients in the chemotherapy-only group (CR: 52.0% vs 46.2%, OS: 58% vs 44%)[30]. Primary gastrointestinal T/HRBCL is a highly aggressive subtype of DLBCL, and there are currently no large-scale studies on its surgical treatment. Among the 9 previously reported cases of primary gastrointestinal T/HRBCL, only 1 patient with stage I disease was definitively diagnosed by endoscopic biopsy, treated with chemotherapy alone, and survived after 1 year of follow-up[15]. Four of the 9 patients underwent surgery combined with chemotherapy, of whom 1 patient with stage I disease underwent surgery combined with chemotherapy and experienced no tumor recurrence after 2 years of follow-up[10]. Two patients underwent surgery due to gastrointestinal perforation[9,11], one of whom died 4 days after surgery alone[9]. According to these reports, surgical treatment for patients with gastrointestinal T/HRBCL can still be performed according to the protocol for intestinal DLBCL. Patients with stage I-II intestinal DLBCL may receive surgery due to a definitive diagnosis, resection of the lesion, or recurrence after treatment, and these patients may benefit more from surgery combined with chemotherapy. In contrast, patients with stage IV disease may undergo palliative surgery due to certain complications, and chemotherapy is given based on the patient's condition to improve clinical symptoms, increase quality of life, reduce lesion size, and prolong survival. For PDL patients with biliary obstruction, biliary drainage can be performed through endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography drainage to alleviate biliary obstruction and prepare for subsequent chemotherapy or surgical treatment[17].

In summary, primary duodenal T/HRBCL is a relatively rare and highly aggressive tumor, so early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving disease prognosis. The diagnosis of gastrointestinal T/HRBCL requires a comprehensive evaluation of the patient's clinical, imaging, endoscopic, and histopathological manifestations. When endoscopic biopsy fails to establish a diagnosis or acute complications occur, surgical exploration can be performed promptly to establish a diagnosis and manage complications. The initial treatment of gastrointestinal T/HRBCL should include individualized treatment strategies based on the original site of the lesion, disease stage, and the patient's physical condition. To date, comprehensive chemotherapy-based treatment is still the main treatment method for gastrointestinal T/HRBCL.

| 1. | Iwamuro M, Tanaka T, Okada H. Review of lymphoma in the duodenum: An update of diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:1852-1862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wang F, Chen L, Liu L, Jia Y, Li W, Wang L, Zhi J, Liu W, Li W, Li Z. Deep learning model for predicting the survival of patients with primary gastrointestinal lymphoma based on the SEER database and a multicentre external validation cohort. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:12177-12189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fujishima F, Katsushima H, Fukuhara N, Konosu-Fukaya S, Nakamura Y, Sasano H, Ichinohasama R. Incidence Rate, Subtype Frequency, and Occurrence Site of Malignant Lymphoma in the Gastrointestinal Tract: Population-Based Analysis in Miyagi, Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2018;245:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang J, Han J, Xu H, Tai S, Xie X. Primary duodenal papilla lymphoma producing obstructive jaundice: a case report. BMC Surg. 2022;22:110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abramson JS. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: biology, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11:384-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ollila TA, Reagan JL, Olszewski AJ. Clinical features and survival of patients with T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60:3426-3433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tóth J, Elek G. Histiocytic and t-cell rich b-cell lymphoma (TCRBCL) of the stomach. Pathol Oncol Res. 1997;3:219-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Barut F, Kandemir NO, Gun BD, Ozdamar SO. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma of stomach. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66:905-907. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Zehani A, Houcine Y, Chelly I, Haouet S, Kchir N. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma of stomach: a rare variant of gastric B cell lymphoma. Tunis Med. 2017;95:504-505. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Tan YH, Chen XY, Yang RG, Wen H, Tang K, Li YZ, Cheng W. [Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma rich in T cells in the stomach: a case report]. Xiandai Yiyao Weisheng. 2018;34:3419-3420. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Sogunro OA, Steinhauer R, Lewis E. T cell/histiocyte rich B-cell lymphoma: A difficult diagnosis to make. Curr Prob Cancer Case Rep. 2020;2:100041. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Udhreja PR, Sapariya BJ. T-cell/histiocyte rich B-cell lymphoma of mass in caecum and part of ascending colon. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:585-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Agrawal V, Bhargav M, Sharma S, Gopal VR. T cell/histiocyte rich large B cell lymphoma of ascending colon: a rare entity. Int Surg J. 2020;7:918. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Li WP, Du Y, Kong ZY, Wang B, Xu XH, Zhu LL, Wang Y. [T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma of ileum with colon adenocarcinoma: a case report]. Zhonghua Jiepou Yu Linchuang Zazhi. 2019;24:419-420. |

| 15. | Köksal AR, Alkim H, Ergun M, Boga S, Bayram M, Alkim C, Eryilmaz OT. First case of T-cell/histiocyte-rich-large B-cell lymphoma presenting with duodenal obstruction. Libyan J Med. 2013;8:22955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yildirim N, Oksüzoğlu B, Budakoğlu B, Vural M, Abali H, Uncu D, Zengin N. Primary duodenal diffuse large cell non-hodgkin lymphoma with involvement of ampulla of Vater: report of 3 cases. Hematology. 2005;10:371-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Peter U, Honegger H, Koelz HR. Obstructive jaundice caused by primary duodenal lymphoma. Case report and review of the literature. Digestion. 2007;75:124-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Andrews CN, John Gill M, Urbanski SJ, Stewart D, Perini R, Beck P. Changing epidemiology and risk factors for gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a North American population: population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1762-1769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen Y, Chen Y, Chen S, Wu L, Xu L, Lian G, Yang K, Li Y, Zeng L, Huang K. Primary Gastrointestinal Lymphoma: A Retrospective Multicenter Clinical Study of 415 Cases in Chinese Province of Guangdong and a Systematic Review Containing 5075 Chinese Patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fujiya M, Kashima S, Ikuta K, Dokoshi T, Sakatani A, Tanaka K, Ando K, Ueno N, Tominaga M, Inaba Y, Ito T, Moriichi K, Tanabe H, Saitoh Y, Kohgo Y. Decreased numbers of vascular networks and irregular vessels on narrow-band imaging are useful findings for distinguishing intestinal lymphoma from lymphoid hyperplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:1064-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tran QT, Nguyen Duy T, Nguyen-Tran BS, Nguyen-Thanh T, Ngo QT, Tran Thi NP, Le V, Dang-Cong T. Endoscopic and Histopathological Characteristics of Gastrointestinal Lymphoma: A Multicentric Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:2767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu Y, Liu JQ, Yang XJ. Usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound for acquiring the pathological diagnosis of gastrointestinal lymphoma. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2022;23:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fischbach W, Dragosics B, Kolve-Goebeler ME, Ohmann C, Greiner A, Yang Q, Böhm S, Verreet P, Horstmann O, Busch M, Dühmke E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Wilms K, Allinger S, Bauer P, Bauer S, Bender A, Brandstätter G, Chott A, Dittrich C, Erhart K, Eysselt D, Ellersdorfer H, Ferlitsch A, Fridrik MA, Gartner A, Hausmaninger M, Hinterberger W, Hügel K, Ilsinger P, Jonaus K, Judmaier G, Karner J, Kerstan E, Knoflach P, Lenz K, Kandutsch A, Lobmeyer M, Michlmeier H, Mach H, Marosi C, Ohlinger W, Oprean H, Pointer H, Pont J, Salabon H, Samec HJ, Ulsperger A, Wimmer A, Wewalka F. Primary gastric B-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. The German-Austrian Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1191-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Boudová L, Torlakovic E, Delabie J, Reimer P, Pfistner B, Wiedenmann S, Diehl V, Müller-Hermelink HK, Rüdiger T. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma with nodules resembling T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: differential diagnosis between nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;102:3753-3758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bouabdallah R, Mounier N, Guettier C, Molina T, Ribrag V, Thieblemont C, Sonet A, Delmer A, Belhadj K, Gaulard P, Gisselbrecht C, Xerri L. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphomas and classical diffuse large B-cell lymphomas have similar outcome after chemotherapy: a matched-control analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1271-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim YS, Ji JH, Ko YH, Kim SJ, Kim WS. Matched-pair analysis comparing the outcomes of T cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma in patients treated with rituximab-CHOP. Acta Haematol. 2014;131:156-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Robin ET, Drill E, Batlevi CL, Caron P, Falchi L, Hamilton A, Hamlin PA, Horwitz SM, Intlekofer AM, Joffe E, Kumar A, Matasar MJ, Noy A, Owens C, Palomba ML, Rodriguez-rivera I, Straus DJ, Vardhana S, von Keudell GR, Zelenetz AD, Moskowitz CH, Moskowitz AJ. Favorable Outcomes Among Patients with T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma Treated with Higher-Intensity Therapy in the Rituximab Era. Blood. 2020;136:36-38. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nair R, Ogundipe I, Gunther J, Medeiros LJ, Jain P, Nastoupil LJ, Pinnix CC, Malpica L, Ahmed S, Miranda R, Fayad L, Steiner RE, Hagemeister F, Lee HJ, Rodriguez MA, Strati P, Chihara D, Wang M, Nieto Y, Ramdial J, Al Zaki A, Nze C, Green MR, Dabaja BS, Xu J, Thakral B, Neelapu SS, Vega F, Flowers CR, Fang P, Westin J, Feng L, Iyer SP. Outcomes in Patients with Relapsed Refractory T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma Treated with CAR-T Cell Therapies or Salvage Chemotherapy - a Single-Institution Experience. Blood. 2023;142:6327-6327. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | El Weshi A, Akhtar S, Mourad WA, Ajarim D, Abdelsalm M, Khafaga Y, Bazarbashi S, Maghfoor I. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: Clinical presentation, management and prognostic factors: report on 61 patients and review of literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1764-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim SJ, Kang HJ, Kim JS, Oh SY, Choi CW, Lee SI, Won JH, Kim MK, Kwon JH, Mun YC, Kwak JY, Kwon JM, Hwang IG, Kim HJ, Park J, Oh S, Huh J, Ko YH, Suh C, Kim WS. Comparison of treatment strategies for patients with intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: surgical resection followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Blood. 2011;117:1958-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |