Published online Jan 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i1.97596

Revised: October 23, 2024

Accepted: November 12, 2024

Published online: January 27, 2025

Processing time: 207 Days and 4.4 Hours

Malignant obstructive jaundice (MOJ) is characterized by the presence of mali

To evaluate the clinical effect of stent placement during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for relieving MOJ and the efficacy of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in terms of liver function improvement, compli

The clinical data of 59 patients with MOJ who were admitted to our hospital between March 2018 and August 2019 were retrospectively analyzed. According to the treatment method, the patients were divided into an observation group (29 patients) and a control group (30 patients). General data, liver function indices, complications, adverse effects, and 3-year survival rates after different surgical treatments were recorded for the two groups.

There were no significant differences in baseline information (sex, age, tumor type, or tumor diameter) between the two groups (P > 0.05). Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and total bilirubin levels were significantly better in both groups after surgery than before surgery (P < 0.05). The overall incidence of biliary bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, and cholangitis was 6.9% in the observation group and 30% in the control group (P < 0.05). No significant differences in the rates of blood transfusion, intensive care unit admission, or death within 3 years were observed between the two groups at the 1-month follow-up (P > 0.05). The 3-year survival rates were 46.06% and 39.71% in the observation and control groups, respectively.

Endoscopic biliary stenting effectively relieves MOJ and significantly improves liver function, with minimal complications. This technique is a promising palliative approach for patients ineligible for radical surgery. How

Core Tip: This study evaluated the clinical efficacy of endoscopic biliary stenting in the treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice. The findings demonstrate that endoscopic treatment significantly improves liver function and is associated with fewer complications than percutaneous biliary drainage. Although the survival rates between the two groups were not markedly different, the observation group presented better short-term clinical outcomes. These findings suggest that endoscopic biliary stenting is a valuable treatment option for patients with malignant obstructive jaundice, especially those ineligible for radical surgery.

- Citation: Wang W, Zhang C, Li B, Yuan GYL, Zeng ZW. Clinical evaluation of endoscopic biliary stenting in treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(1): 97596

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i1/97596.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i1.97596

Malignant obstructive jaundice (MOJ) refers to obstruction of the bile duct caused by malignant tumors such as liver cancer, bile duct cancer, and pancreatic cancer, either within or outside the liver. These obstructions prevent bile excretion, leading to abnormally elevated serum bilirubin levels and subsequent jaundice[1,2]. It has been reported that less than 20% of individuals with MOJ and malignant tumors are suitable for aggressive surgical treatment[3]. Continuous biliary obstruction in patients with MOJ allows bacteria and their endotoxins from the duodenum to flow back into the bloodstream through the biliary-venous pathway, leading to severe infection and sepsis[4]. Additionally, the accumulation of toxic bile salts and bilirubin due to biliary obstruction can cause hyperbilirubinemia[5,6], which may gradually lead to the development of cholestatic cirrhosis and irreversible hepatocyte damage[7]. This accumulation impacts the metabolic and synthetic capacity of liver cells, impairing the patient’s immune and coagulation functions[8], thus reducing their quality of life and survival time. Consequently, MOJ patients with a life expectancy of more than three months who are not eligible for resection should undergo palliative biliary drainage. This intervention can help alleviate clinical symptoms related to biliary obstruction, improve liver function, and enhance the patient’s immune response, thereby extending the survival time[9,10].

With advancements in endoscopic and imaging technologies, the treatment approach for patients with MOJ who are not candidates for radical surgery has gradually transitioned to minimally invasive interventions. Among these, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) stenting, referred to as endoscopic biliary support in this study, is widely employed for biliary drainage. For patients unable to undergo ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic biliary dra

The clinical data from 59 patients who were diagnosed with MOJ and admitted to two hospitals between March 2018 and August 2019 were retrospectively analyzed in this study. The patients received treatment at Wuhan No. 1 Hospital. The objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of endoscopic biliary stenting with that of PTBD. On the basis of the treatment method use, the patients were divided into two groups: Observation group (29 patients), which underwent endoscopic biliary stenting, and control group (30 patients), which underwent PTBD. Patients were grouped to ensure that the focus remained on stent placement during ERCP and to facilitate a direct comparison between stent placement during ERCP and PTBD.

Inclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria for the study included patients who were diagnosed with obstructive jaundice caused by various malignant tumors and presented with symptoms such as abdominal pain, jaundice, pruritus, fatigue, and anorexia. These patients had undergone either endoscopic biliary stent placement or PTBD, had not undergone any other relevant surgical treatment, exhibited stable vital signs, and had normal cognitive and neurological functions.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded from the study if they had diseases of the blood or immune system, dys

Both groups underwent identical preoperative preparation procedures, including confirmation of their condition, routine biochemical and coagulation tests, correction of electrolyte imbalances, fasting before surgery, intramuscular injection of 5 mg diazepam for sedation, and intravenous injection of 10-20 mg of 654-2 anisodamine for additional sedation and spasmolysis.

The patients in the control group underwent PTBD. Under ultrasound guidance, the bile duct or the bile duct in the right liver (dilated state) was selected as the main puncture point for the procedure. An 18G needle was used to puncture the bile duct, and the needle was inserted into the liver to extract the bile. If the metal guidewire successfully entered the common bile duct and duodenum, intrahepatic and external drainage was performed. The catheter was externally fixed after confirmation of the correct position by imaging. An extrahepatic catheter was used for drainage if it could not be inserted smoothly.

The patients in the observation study group underwent endoscopic biliary stenting. Conventional imaging was per

After the procedure, primary care included close monitoring of vital signs such as blood pressure and heart rate. Patients received symptomatic support treatment, including acid suppression, enzyme suppression, liver protection, anti-infection measures, and rehydration, to maintain the water electrolyte balance. Patients were advised to fast from food and water for 24 hours postoperatively. Close observation of abdominal symptoms and signs was conducted, and blood amylase levels were measured on postoperative day 1. Liver function was monitored at least once between postoperative days 1 and 3 and again between days 4 and 7 to assess jaundice resolution.

Biliary tract infection: Postoperative antibiotic treatment was administered, and efforts were made to ensure adequate drainage.

Acute pancreatitis: Early fluid resuscitation, dynamic assessment of disease progression, maintenance of water and electrolyte balance, organ function support, and active prevention and treatment of local and systemic complications were provided. Surgical intervention was considered if necessary.

Perforation: Continuous gastrointestinal decompression was employed, along with measures to maintain water, elec

Bleeding: Hemostasis was achieved via techniques such as submucosal epinephrine injection, electrocoagulation, metal clip placement, or column balloon compression. If hemostasis was difficult, the placement of fully covered metal stents was considered to control bleeding. If these methods were ineffective, vascular intervention or surgical treatment was performed.

The incidence of complications and adverse events during hospitalization was also recorded. After discharge, the patients were followed via telephone at regular intervals: Every 2 months during the first year, every 3 months in the second year, and every 6 months in the third year. The incidence of adverse events and survival rates were documented throughout the follow-up period.

Admission observation indices: The admission observation indices included the patient’s age, sex, underlying cause of MOJ, level of bile duct obstruction, number of stents placed, presence of preoperative biliary tract infection, liver function based on the Child-Pugh grade, presence of peritoneal effusion, intrahepatic lesions, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and liver function indicators at different time points.

Liver function Child-Pugh grade: The Child-Pugh classification is a common clinical grading system for the quantitative assessment of liver reserve function. Five indicators are evaluated: Hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, total bilirubin (TBIL), and albumin levels, and prothrombin time. Each indicator was scored between 1 point and 3 points. The total score determines the liver function grade, with a higher score indicating worse liver reserve capacity. Grade A corresponds to a score of 5-6 points, grade B corresponds to a score of 7-9 points, and grade C corresponds to a score of 10-15 points.

Efficacy indices: Efficacy indices included liver function test values measured at different time points postoperatively, specifically at 1-3 days, 4-7 days, and 1 month after surgery. The liver function test results closest to the time of surgery were taken as the preoperative value, while the latest test results during each of the specified postoperative periods were used for the analysis. For patients returning to the hospital for review 1 month after surgery, the current liver function test results were included. Postoperative complications during the current hospitalization, including biliary tract infections, acute pancreatitis, biliary bleeding, and perforation, were also recorded. The diagnostic criteria for these complications were based on the 2018 edition of the Chinese ERCP guidelines[16].

Biliary tract infection: The patient was diagnosed with abdominal pain, jaundice, and hyperthermia. When combined with shock and psychiatric symptoms, this suggests acute suppurative cholangitis.

Acute pancreatitis: At least two of the following three criteria must be met for diagnosis: (1) Symptoms of abdominal pain consistent with acute pancreatitis; (2) Serum amylase and/or lipase levels ≥ 3 times the upper limit of normal; and (3) Imaging findings consistent with acute pancreatitis.

Biliary hemorrhage: It is identified by the presence of right upper abdominal pain, upper gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., black stool and vomiting blood), or jaundice. In some cases, all three manifestations may occur simultaneously.

Perforation: There is severe abdominal pain with clinical signs of acute diffuse peritonitis. X-rays showing free gas under the diaphragm or extraction of digestive fluid containing gastric contents during a diagnostic abdominal puncture confirmed the diagnosis.

The success criteria for the operation were as follows: Successful insertion of the catheter at the opening of the duodenal papilla, correct placement and fixation of the stent along the guidewire, and drainage of the bile into the duodenum under endoscopic observation after stent placement. In addition, a postoperative plain abdominal film confirming that the stent was in the correct position indicated procedural success.

Efficacy assessment 4-7 days after surgery: Efficacy was considered significant if the patient’s skin and scleral jaundice visibly improved compared with the preoperative state and if TBIL levels decreased by more than 30% from the pre

Patient follow-up 1 month after surgery: Patients whose TBIL levels had returned to the normal range were considered to have achieved good recovery. If the TBIL levels remained abnormal, recovery was classified as poor.

SPSS version 26 was used for the statistical analyses in this study. All the data were tested for normality. Data that followed a normal distribution are expressed as the mean ± SD, and comparisons between the two groups were conducted using t tests. Data that did not follow a normal distribution are expressed as medians (with interquartile ranges), and comparisons between groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are ex

There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics, including sex, age, tumor type, or tumor diameter, between the observation group (n = 29) and the control group (n = 30) (P > 0.05 for all comparisons). These findings suggest that the two groups were comparable at baseline. The details of the baseline data are presented in Table 1.

| Index | Observation group (n = 29) | Control group (n = 30) | t/χ² | P value |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 18 | 17 | 0.178 | 0.673 |

| Female | 11 | 13 | / | / |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 52.68 ± 3.65 | 53.48 ± 3.62 | 1.205 | 0.230 |

| Tumor type | ||||

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 6 | 7 | 0.060 | 0.807 |

| Gallbladder cancer | 7 | 8 | 0.050 | 0.823 |

| Liver cancer | 6 | 4 | 0.685 | 0.165 |

| Ampullary carcinoma | 3 | 5 | 0.108 | 0.742 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 7 | 6 | 0.098 | 0.754 |

| Tumor diameter | ||||

| < 3 cm | 11 | 12 | 0.027 | 0.871 |

| ≥ 3 cm | 18 | 18 | / | / |

Liver function indicators, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and TBIL, were compared between the observation group and the control group before and after surgery. There was no significant difference in preoperative liver function values between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, the postoperative ALT, AST, and TBIL levels were significantly lower than the preoperative levels in both groups (P < 0.05). No significant difference in postoperative liver function indicators was found between the two groups (P > 0.05). The detailed comparisons are shown in Table 2.

| Indicator | Observation group (n = 29) | Control group (n = 30) | t | P value |

| ALT (U/L) | ||||

| Preoperative | 107.66 ± 45.66 | 101.54 ± 42.68 | 0.759 | 0.450 |

| Postoperative | 49.66 ± 6.26a | 52.81 ± 6.74a | 1.859 | 0.068 |

| AST (U/L) | ||||

| Preoperative | 129.66 ± 11.29 | 126.34 ± 10.75 | 1.650 | 0.102 |

| Postoperative | 74.89 ± 6.31a | 78.43 ± 7.89a | 1.899 | 0.063 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | ||||

| Preoperative | 186.58 ± 59.38 | 189.61 ± 60.59 | 0.783 | 0.277 |

| Postoperative | 90.65 ± 50.11a | 104.64 ± 47.65a | 1.099 | 0.276 |

The occurrence of complications, including biliary tract bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, and cholangitis, was compared between the two groups. The total incidence of complications in the observation group (6.9%) was significantly lower than that in the control group (30%) (P < 0.05). The detailed incidence rates for each complication are presented in Table 3.

| Group | Biliary tract bleeding | Gastrointestinal bleeding | Pancreatitis | Cholangitis | Total incidence |

| Observation group (n = 29) | 1 (3.45) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.45) | 2 (6.90) |

| Control group (n = 30) | 2 (6.67) | 3 (10.00) | 1 (3.33) | 3 (10.00) | 9 (30.00) |

| P value | - | - | - | - | 0.023 |

| χ² | - | - | - | - | 5.189 |

The incidence of adverse events, including blood transfusion, intensive care unit admission, and death within 1 month after surgery, was compared between the two groups. There was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of these adverse events between the two groups (P > 0.05 for all comparisons). The detailed incidence rates are presented in Table 4.

| Group | Blood transfusion within 1 month | ICU admission | Death within 3 years |

| Observation group (n = 29) | 16 (55.17) | 17 (58.62) | 11 (37.93) |

| Control group (n = 30) | 21 (70.00) | 22 (73.33) | 13 (43.33) |

| χ² | 1.386 | 1.425 | 0.178 |

| P value | 0.239 | 0.233 | 0.673 |

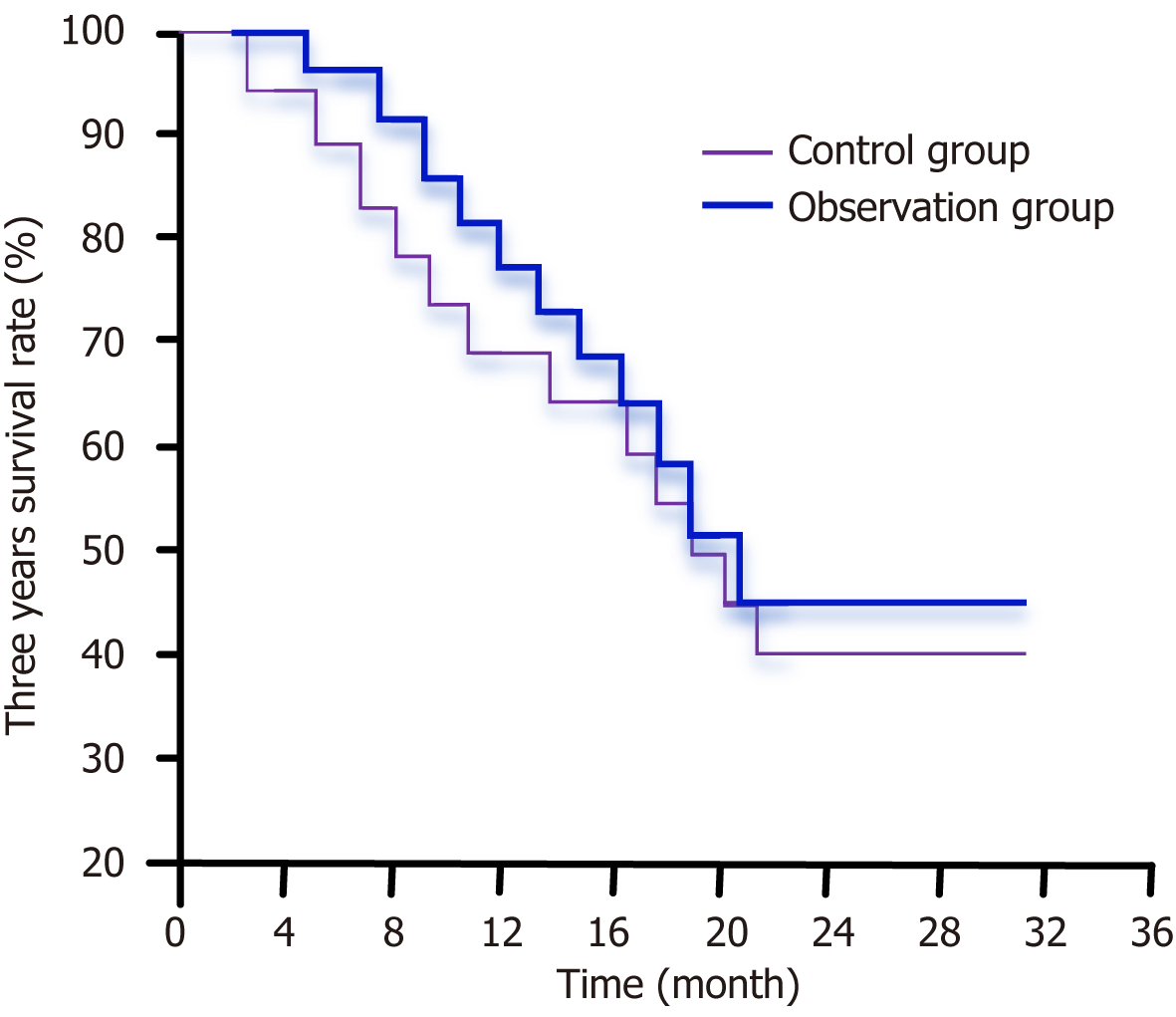

The 3-year survival rates in the observation and control groups were 46.06% and 39.71%, respectively. Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in the 3-year survival rates between the two groups (P = 0.524), as illustrated in Figure 2.

MOJ is a condition caused by the infiltration or compression of the bile duct by malignant tumors, particularly pancreatic head tumors, gallbladder and bile duct tumors, liver malignancies, tumors in the periampullary region, or enlarged lymph nodes compressing the bile duct. This condition leads to inadequate bile drainage, resulting in symptoms such as jaundice, pain, pruritus (itching), and general weakness. The etiology of bile duct cancer and pancreatic head cancer is commonly linked to advanced age, predominantly affecting the elderly population. Since the beginning of the 21st cen

Owing to the insidious onset and highly malignant nature of these conditions, early clinical manifestations are often absent. As a result, most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage when surgery is unlikely to lead to a cure; notably, only approximately 20% of patients are suitable for curative surgical treatment at the time of diagnosis[18]. Surgical resection is the main curative treatment for malignant tumors; however, there is potential for reducing the tumor stage in clinical practice to ultimately increase the possibility of surgical resection. Currently, neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be used to reduce tumor stage, thereby increasing the possibility of curative surgery. However, the long-term survival rate remains unsatisfactory despite surgical intervention. Studies have shown that even among those who undergo curative surgery, 60%-80% of patients die within 5 years after surgery, indicating a very poor prognosis[19]. If left untreated, most patients die within 6 months after their initial diagnosis[20].

The primary reason for this high mortality rate is that after bile stasis occurs, bilirubin enters the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammatory response syndrome and leading to multiple organ dysfunction. This progression sign

All patients who received conventional treatment or underwent endoscopic biliary stenting were included in this study. The general data of patients with MOJ in both groups were not statistically significant for follow-up purposes. Liver function indices before and after surgery were compared between the two groups to assess the impact of surgery on MOJ liver function and to evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic biliary stenting. The results revealed that both groups of patients exhibited significant improvement after receiving different surgical treatments, as evidenced by ALT, TBIL, and AST levels that were significantly better than the preoperative levels. Postoperatively, the ALT, TBIL, and AST levels in the observation group were lower than those in the control group. Both procedures were effective in alleviating MOJ, as evidenced by good outcomes. In patients with MOJ, the ability of the liver to metabolize bilirubin is impaired, leading to the accumulation of bilirubin in the blood and elevated bilirubin levels. When the liver is damaged, a large amount of ALT is released into the bloodstream, and necrosis of only 1% of hepatocytes can increase blood enzyme activity by up to 100%. After MOJ, ALT and AST levels are elevated, often to tens or even hundreds of times higher than normal. The correction of MOJ leads to significant decreases in ALT, TBIL, and AST levels[23,24].

Further evaluation of complications during the procedure revealed that the incidence of postoperative bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, and cholangitis was consistently lower in patients who underwent en

Previous studies have shown that endoscopic biliary stenting can alleviate MOJ, prolong survival, and improve patient quality of life[29,30]. In this study, a 3-year follow-up was conducted to analyze the survival rates of the patients. The results indicated that the 3-year survival rate in the observation group was higher than that of the control group (46.06% vs 39.71%), although this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.524). This suggests that neither of the methods had more survival benefits than the other. These findings are consistent with previous research, which showed that while endoscopic techniques can reduce the incidence of complications, long-term survival outcomes remain unchanged due to the malignant nature of the underlying conditions[27,28].

This result is likely because all MOJ patients in this study had malignant tumors, and the survival period for patients with such tumors is inherently shorter, contributing to the low postoperative survival rate. Higher postoperative survival rates are likely observed in patients with benign tumors. However, in cases of malignant tumors, surgical removal is unlikely to cure the underlying cancer in a timely manner. This study highlights the value of endoscopic biliary stenting as a palliative treatment for MOJ. These findings demonstrate that this method significantly improves liver function and is associated with a low complication rate, thus indicating its suitability as a more effective and safer option for patients who are ineligible for radical surgery. These results underscore the clinical utility of endoscopic biliary stenting during ERCP for relieving MOJ symptoms and enhancing patient outcomes. A novel aspect of this study was the direct comparison between endoscopic biliary stenting and PTBD, a commonly used alternative. However, PTBD has not been frequently compared with ERCP in terms of complication rates, liver function improvement, and long-term survival. This head-to-head comparison highlights the advantages of ERCP, providing practical insights for clinicians in selecting the most appropriate treatment option for patients with MOJ.

Moreover, this study is clinically relevant in that data were collected from multiple hospitals, thus enhancing the generalizability and reliability of the findings. This approach is beneficial for highlighting the benefits of endoscopic biliary stenting and the need for its widespread adoption across different clinical settings. Additionally, while many studies have focused primarily on survival rates, this study emphasizes the importance of improving liver function and reducing the incidence of complications, both of which are important. In palliative care settings, a focus on quality of life is particularly important, as enhancing patient well-being takes precedence. Finally, this paper identifies gaps in the management of non-MOJ and suggests the potential for future advancements in treatment, such as the integration of immune-based or genetic therapies. These forward-looking approaches suggest that endoscopic biliary stenting could eventually be considered a comprehensive treatment strategy for both malignant and nonmalignant cases of obstructive jaundice.

This study demonstrated that endoscopic biliary stenting during ERCP is an effective palliative treatment for patients with MOJ, as it, compared with PTBD, significantly improves liver function and reduces complication rates. The patients in the ERCP group presented better postoperative liver enzyme profiles and lower rates of biliary bleeding, gastro

| 1. | Silina EV, Stupin VA, Abramov IS, Bolevich SB, Deshpande G, Achar RR, Sinelnikova TG. Oxidative Stress and Free Radical Processes in Tumor and Non-Tumor Obstructive Jaundice: Influence of Disease Duration, Severity and Surgical Treatment on Outcomes. Pathophysiology. 2022;29:32-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Asare OK, Osei F, Appau AAY, Sarkodie BD, Tachi K, Nkansah AA, Acheampong T, Nwaokweanwe C, Olayiwola D. Aetiology of Obstructive Jaundice in Ghana: A Retrospective Analysis in a Tertiary Hospital. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2020;10:36-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | An J, Dong Y, Li Y, Han X, Sha J, Zou Z, Niu H. Retrospective analysis of T-lymphocyte subsets and cytokines in malignant obstructive jaundice before and after external and internal biliary drainage. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060520970741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li J, Zhuo S, Chen B, Liu Y, Wu H. Clinical efficacy of laparoscopic modified loop cholecystojejunostomy for the treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060519866285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alsaigh S, Aldhubayb MA, Alobaid AS, Alhajjaj AH, Alharbi BA, Alsudais DM, Alhothail HA, AlSaykhan MA. Diagnostic Reliability of Ultrasound Compared to Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in the Detection of Obstructive Jaundice: A Retrospective Medical Records Review. Cureus. 2020;12:e10987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jin H, Pang Q, Liu H, Li Z, Wang Y, Lu Y, Zhou L, Pan H, Huang W. Prognostic value of inflammation-based markers in patients with recurrent malignant obstructive jaundice treated by reimplantation of biliary metal stents: A retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e5895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li Z, Jiao D, Han X, Liu Z. A Comparative Study of Self-Expandable Metallic Stent Combined with Double (125)I Seeds Strands or Single (125)I Seeds Strand in the Treatment of Advanced Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma with Malignant Obstructive Jaundice. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:4077-4086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Okamoto T. Malignant biliary obstruction due to metastatic non-hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:985-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Gao Z, Wang J, Shen S, Bo X, Suo T, Ni X, Liu H, Huang L, Liu H. The impact of preoperative biliary drainage on postoperative outcomes in patients with malignant obstructive jaundice: a retrospective analysis of 290 consecutive cases at a single medical center. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Emara MH, Zaghloul MS, Mahros AM, Emara EH. Choledocho-nodal Fistula: Uncommon Cause of Obstructive Jaundice in a Patient with HCC Diagnosed by Combined ERCP/EUS. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2021;11:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moole H, Bechtold M, Puli SR. Efficacy of preoperative biliary drainage in malignant obstructive jaundice: a meta-analysis and systematic review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sarkodie BD, Botwe BO, Brakohiapa EKK. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary stent placement in the palliative management of malignant obstructive jaundice: initial experience in a tertiary center in Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sportes A, Camus M, Greget M, Leblanc S, Coriat R, Hochberger J, Chaussade S, Grabar S, Prat F. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy versus percutaneous transhepatic drainage for malignant biliary obstruction after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a retrospective expertise-based study from two centers. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:483-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sha J, Dong Y, Niu H. A prospective study of risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with malignant obstructive jaundice undergoing percutaneous biliary drainage. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhao B, Cheng Q, Cao H, Zhou X, Li T, Dong L, Wang W. Dynamic change of serum CA19-9 levels in benign and malignant patients with obstructive jaundice after biliary drainage and new correction formulas. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mukai S, Itoi T, Baron TH, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Ukai T, Shikata S, Teoh AYB, Kim MH, Kiriyama S, Mori Y, Miura F, Chen MF, Lau WY, Wada K, Supe AN, Giménez ME, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Indications and techniques of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis in updated Tokyo Guidelines 2018. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:537-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yousaf MN, Ehsan H, Wahab A, Muneeb A, Chaudhary FS, Williams R, Haas CJ. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography guided interventions in the management of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;12:323-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Qi S, Yan H. Effect of percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainag + radiofrequency ablation combined with biliary stent implantation on the liver function of patients with cholangiocarcinoma complicated with malignant obstructive jaundice. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:1817-1824. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Zhu KX, Yue P, Wang HP, Meng WB, Liu JK, Zhang L, Zhu XL, Zhang H, Miao L, Wang ZF, Zhou WC, Suzuki A, Tanaka K, Li X. Choledocholithiasis characteristics with periampullary diverticulum and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedures: Comparison between two centers from Lanzhou and Kyoto. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:132-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bao G, Liu H, Ma Y, Li N, Lv F, Dong X, Chen X. The clinical efficacy and safety of different biliary drainages in malignant obstructive jaundice treatment. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:7400-7405. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Zerem E, Imširović B, Kunosić S, Zerem D, Zerem O. Percutaneous biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice in patients with inoperable, malignant biliary obstruction. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;8:70-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ma BQ, Chen SY, Jiang ZB, Wu B, He Y, Wang XX, Li Y, Gao P, Yang XJ. Effect of postoperative early enteral nutrition on clinical outcomes and immune function of cholangiocarcinoma patients with malignant obstructive jaundice. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:7405-7415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pausawasdi N, Termsinsuk P, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Limsrivilai J, Kaosombatwattana U. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting clinical success after endobiliary stenting for malignant biliary obstruction. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0272918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Uyanık SA, Öğüşlü U, Çevik H, Atlı E, Yılmaz B, Gümüş B. Percutaneous endobiliary ablation of malignant biliary strictures with a novel temperature-controlled radiofrequency ablation device. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2021;27:102-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gao DJ, Yang JF, Ma SR, Wu J, Wang TT, Jin HB, Xia MX, Zhang YC, Shen HZ, Ye X, Zhang XF, Hu B. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation plus plastic stent placement versus stent placement alone for unresectable extrahepatic biliary cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:91-100.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Inoue T, Yoneda M. Updated evidence on the clinical impact of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of malignant biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:345-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Inoue T, Kitano R, Ibusuki M, Kobayashi Y, Ito K, Yoneda M. Simultaneous triple stent-by-stent deployment following endobiliary radiofrequency ablation for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2021;53:E162-E163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lanza D, Casty A, Schlosser SH. Endobiliary Radiofrequency Ablation for Malignant Biliary Obstruction over 32-Month Follow-Up. Gastrointest Tumors. 2022;9:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jarosova J, Macinga P, Hujova A, Kral J, Urban O, Spicak J, Hucl T. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for malignant biliary obstruction. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13:1383-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Khilko Y. Palliative decomprression in malignant obstructive jaundice: focus on the liver function. J Educ Health Sport. 2021;11:433-445. [DOI] [Full Text] |