Published online Jan 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i1.100364

Revised: October 10, 2024

Accepted: October 15, 2024

Published online: January 27, 2025

Processing time: 112 Days and 6.2 Hours

With the continuous development of laparoscopic techniques in recent years, laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LapTME) and laparoscopic-assisted transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) have gradually become important surgical techniques for treating low-lying rectal cancer (LRC). However, there is still controversy over the efficacy and safety of these two surgical modalities in LRC treatment.

To compare the efficacy of LapTME vs TaTME in patients with LRC.

Ninety-four patients with LRC who visited and were treated at the Affiliated Hengyang Hospital of Hunan Normal University & Hengyang Central Hospital between December 2022 and March 2024 were selected and divided into the LapTME (n = 44) and TaTME (n = 50) groups. Clinical operation indexes, post

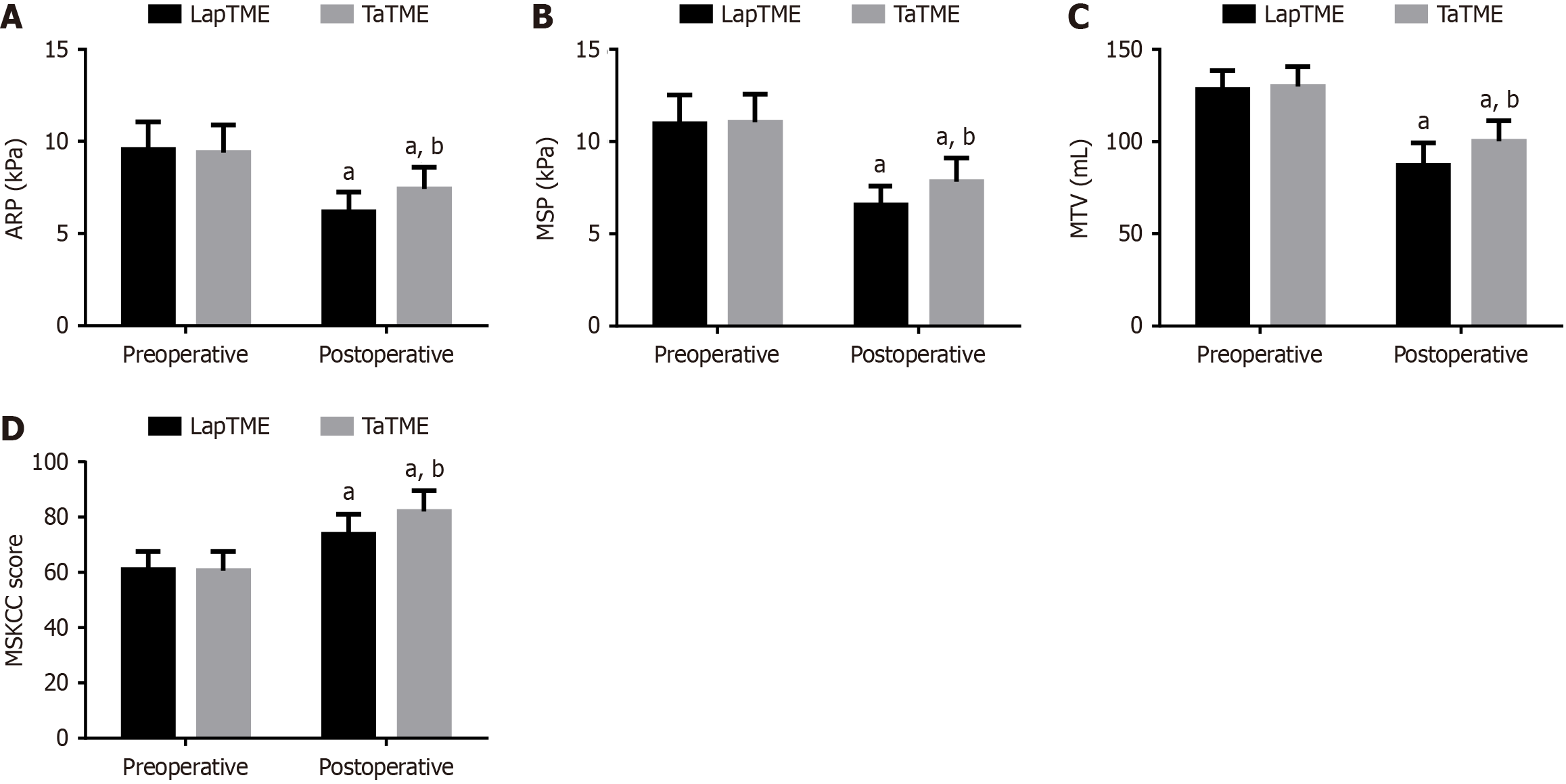

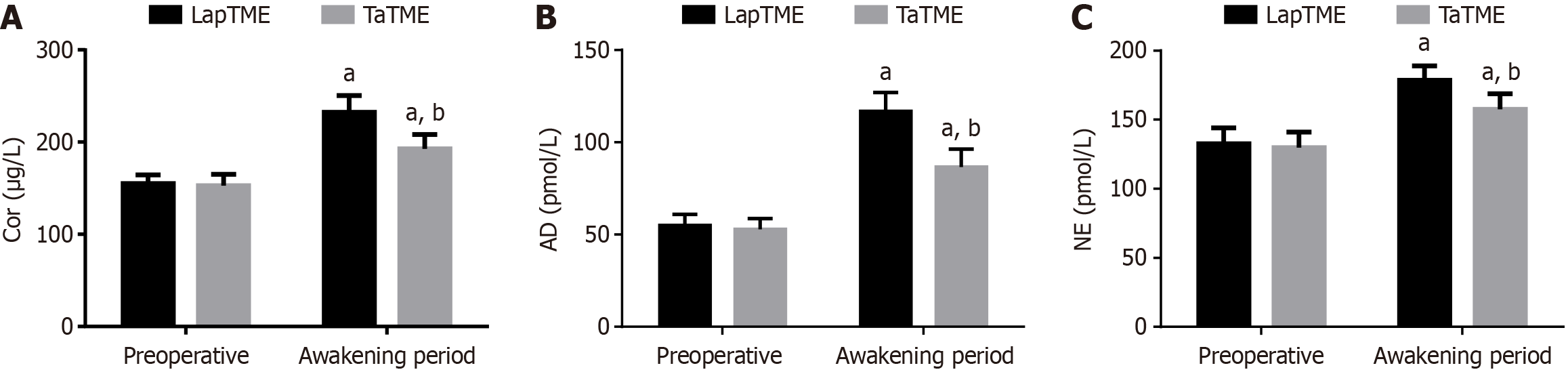

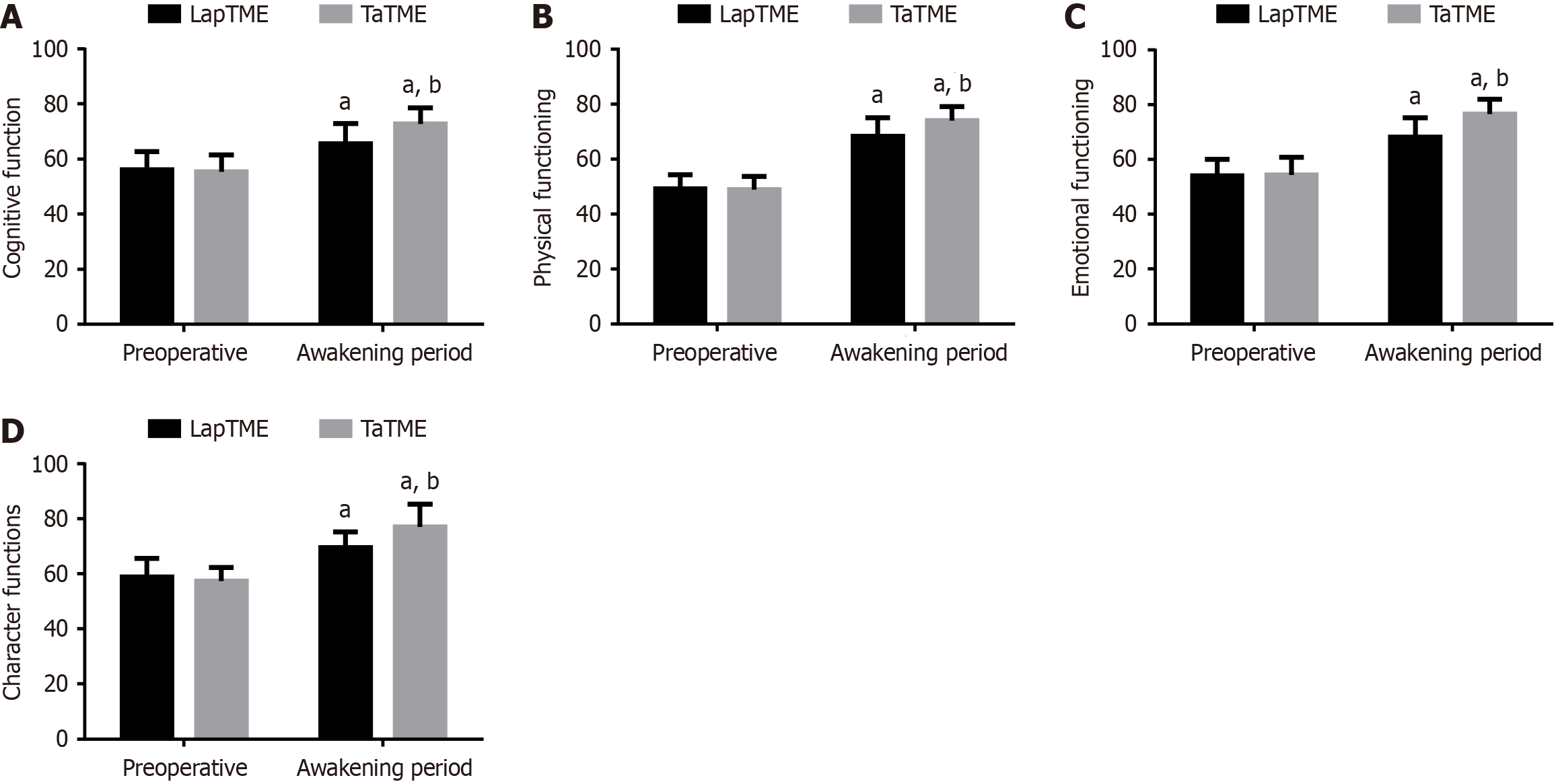

Compared with the LapTME group, the surgery time in the TaTME group was longer; intraoperative blood loss was low; time of anal exhaust, first postoperative ambulation, intestinal recovery, and hospital stay were shorter; and the distal incisal margin and specimen lengths were longer. The TaTME group also showed higher ARP, MSP, and MTV values and higher MSKCC and QLQ-C30 scores than the LapTME group 3 months postoperatively. Cor, AD, and NE levels were lower in the TaTME group than those in the LapTME group during recovery.

We demonstrated that TaTME better improved anal function, reduced postoperative stress, and accelerated postoperative recovery and, hence, was safer for patients with LRC.

Core Tip: Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LapTME) and laparoscopic-assisted transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) are important minimally invasive TME procedures for the treatment of low-lying rectal cancer (LRC); however, their specific efficacy and safety are still controversial. Per our findings, although surgery time with TaTME is longer, it ensures better rectal cancer specimen resection and faster postoperative recovery (anal exhaust, first postoperative ambulation, intestinal recovery, and hospital stay) compared with LapTME. Moreover, TaTME is more effective in improving surgical safety, enhancing anal function, and reducing postoperative stress responses. Therefore, TaTME may be a better choice for treating LRC.

- Citation: Lu F, Tan SG, Zuo J, Jiang HH, Wang JH, Jiang YP. Comparative efficacy analysis of laparoscopic-assisted transanal total mesorectal excision vs laparoscopic transanal mesorectal excision for low-lying rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(1): 100364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i1/100364.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i1.100364

Rectal cancer (RC), a common malignancy that occurs from the pectinate line to the rectum–sigmoid junction, was reported worldwide with 700000 cases and approximately 340000 related deaths in 2020 alone[1]. RC can be classified into two categories based on the location of the lesion, namely distally located RC and low-lying RC (LRC). Compared with the former, the latter’s oncological outcomes are characterized by higher recurrence rates, poorer survival rates, and worse functional outcomes as well as poorer quality of life in those with local recurrence[2]. Total mesorectal excision (TME), associated with excellent long-term local recurrence-free and overall survival rates, is the standard surgical treatment for RC[3]. As laparoscopic technology develops and improves continuously, laparoscopic TME (LapTME) has become the preferred treatment for RC. Compared with traditional open rectal surgery, it can effectively reduce the length of the surgical incision and minimize patient harm while affording greater safety and promoting postoperative recovery[4]. However, for patients with a narrow pelvic space and hypertrophy of the mesorectum, it is difficult to free the intestine below the peritoneal reflection by LapTME, easily causing vascular and nerve damage and leading to incomplete tumor resection[5]. Transanal TME (TaTME) is a novel surgical modality designed to reduce the difficulty of anatomical separation of the pelvic floor, particularly in patients with pelvic stenosis, low-lying tumors, and a high body mass index (BMI)[6]. TaTME has quickly become a hotspot in colorectal surgery since its first clinical application in 2010. However, TaTME as a treatment option for LRC is still in its early stage, warranting more clinical research. In this study, LapTME and laparoscopic-assisted TaTME were performed on patients with LRC to compare the treatment effects of these two surgical modalities.

We included 94 patients with LRC who underwent surgery at the Affiliated Hengyang Hospital of Hunan Normal University & Hengyang Central Hospital from December 2022 to March 2024. Depending on the surgical modality employed, they were assigned to either the LapTME (44 cases) or TaTME groups (50 cases). Our inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Diagnosis of RC by clinicopathological diagnosis; (2) No distant metastasis; and (3) Tumor distance from the anal margin < 8 cm. Our exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Hepatic and renal insufficiency; (2) Coagulation dysfunction; (3) history of malignant colorectal tumors; (4) Pregnant or lactating women; (5) Incomplete clinical data; (6) Surgical contraindications; and (7) Received preoperative chemoradiotherapy.

For patients in the LapTME group, endotracheal intubation was performed under general anesthesia. The patient was placed in the lithotomy position, and pneumoperitoneum (abdominal pressure: 13 mmHg; 1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa) was established by a puncture at the upper edge of the umbilical cord, through which the cannula and laparoscope were inserted. Then, a 12-mm incision was made at the lateral 1st/3rd of the horizontal line of the right anterior superior iliac spine as the main operating hole and a 5-mm incision was made parallel to the umbilical horizontal line on the outer edge of the left and right rectus abdominis as the auxiliary operating hole, through which the operating instruments were placed successively. Then, the sigmoid colon and rectal peritoneum were precisely separated in the presacral space under laparoscopy, and the inferior mesenteric artery was severed while protecting the left colon artery. Then, the rectum was separated along the fascia space of the proper rectum and pelvic wall to the tip of the coccyx, anterior peritoneum of the rectum was incised, and pre-rectal peritoneal reflection was incised to separate the anterior rectal wall from the bladder (rectouterine pouch in females). The bilateral ligaments were severed to protect the pelvic autonomic nerve, and the rectum was free at 3 cm below the tumor. After the cutting stapler was placed, the intestine was incised 5 cm above and 2 cm below the tumor, and the lesion was removed through the main operating hole. Pathological examination was performed to ensure a negative incisal margin, and the sigmoid colon and rectum were anastomosed without tension. After pneumoperitoneum was stopped, the abdominal cavity and pelvic cavity were flushed, instrument was withdrawn, drainage tube was placed, and the abdomen was closed.

For patients in the TaTME group, the anesthesia mode, surgical position, and the positions of laparoscopic holes were the same as those employed for LapTME. Under laparoscopy, the mesorectum was dissociated and lymph nodes at the roots of blood vessels were removed. The mesorectum was dissociated anteriorly to the level of the peritoneal reflection and posteriorly to the level of the fifth sacral vertebra, after which pneumoperitoneum was stopped. Following routine perineal disinfection, the anus was opened and the intestinal cavity was purse-string sutured 2-3 cm below the tumor edge. Then, from the 5 o’clock to 7 o’clock position, the purse-ruffled border was cut into the space around the rectum, and the mesorectum was separated from the bottom up till it met the abdomen. The intestinal tube was then severed, with the incisal margin position the same as that for the LapTME group. The lesion was removed through the anus, and the intestinal tube was pulled out through the anus for sigmoid colon–rectal end-to-end anastomosis, after which the intestinal tube was returned. The surgical area was irrigated, instruments were withdrawn, drainage tubes were placed, and abdominal and perineal incisions were sutured successively.

Both groups were monitored for their vital signs postoperatively and given nutritional support and anti-infection interventions.

An anal pressure detector (ZGJ-D3, Shanghai Hanfei Medical Devices Co., Ltd.) was used to detect the anal resting pressure (ARP), anal maximum systolic pressure (MSP), and maximum tolerated volume (MTV) of the anal canal three days preoperatively and three months postoperatively. The patients’ intestinal function was assessed preoperatively and three months postoperatively with the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) bowel function questionnaire describing frequent and urgent defecation (nine items), defecation affected by diet (four items), and abnormal defecation feeling (four items), each rated as 1-5 points; a higher score suggested a better intestinal function.

The venous blood samples from preoperatively and during the recovery period were centrifuged to collect serum samples for the measurement of norepinephrine (NE), adrenaline (AD), and cortisol (Cor) levels.

The surgery time, intraoperative blood loss, anal exhaust time, first postoperative ambulation, intestinal recovery time, and hospitalization time were recorded. In addition, the distal incisal margin length, specimen length, and the number of lymph nodes cleared were compared. Complications, including anastomotic bleeding, anastomotic fistula, ileus, and incision infection, were also compared between groups.

At 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours postoperatively, the pain level of patients was assessed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The evaluation tool was a 10 cm sliding ruler, with both ends corresponding to no pain (0 points) and severe pain (10 points). A higher score is indicative of more intense pain.

The Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) was used to evaluate the cognitive, physical, emotional, and role functions related to the quality of life before and after treatment, with the highest score of 100 in each field; the score is positively correlated with the quality of life.

GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) was employed for data analyses and visualization. In this study, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons of categorical data. Independent t-test was utilized to identify between-group differences of measurement data, and paired t-test was performed to identify within-group differences across different time periods. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The two groups did not differ statistically in age, BMI, tumor diameter, tumor distance from the anal margin, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists grading, tumor–nodes–metastasis staging, and pathological type (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Groups | LapTME group (n = 44) | TaTME group (n = 50) | χ2/t | P value |

| Age (year) | 61.61 ± 9.26 | 62.98 ± 9.37 | 0.711 | 0.479 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.28 ± 2.68 | 22.95 ± 2.77 | 0.585 | 0.560 |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 3.54 ± 0.75 | 3.48 ± 0.78 | 0.379 | 0.706 |

| Tumor distance from the anal margin (cm) | 4.82 ± 1.81 | 4.93 ± 1.81 | 0.294 | 0.769 |

| Sex | 0.057 | 0.811 | ||

| Male | 28 (63.64) | 33 (66.00) | ||

| Female | 16 (36.36) | 17 (34.00) | ||

| American Society of Anesthesiologists grading | 3.197 | 0.074 | ||

| I | 21 (47.73) | 32 (64.00) | ||

| I | 23 (52.27) | 18 (36.00) | ||

| Tumor–nodes–metastasis staging | 0.437 | 0.509 | ||

| I | 19 (43.18) | 25 (50.00) | ||

| II | 25 (56.82) | 25 (50.00) | ||

| Pathological type | 0.684 | 0.408 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 34 (77.27) | 42 (84.00) | ||

| Others | 10 (22.73) | 8 (16.00) |

Three days before the surgery, no significant inter-group differences were noted with regard to ARP, MSP, and MTV values as well as MSKCC scores (P > 0.05). Three months postoperatively, both groups showed reductions in ARP, MSP, and MTV values; however, higher values of the three indexes were observed in the TaTME group compared with those in the LapTME group (P < 0.05). Regarding the MSKCC score, both groups of patients showed a significant increase in MSKCC scores three months after surgery, with an even higher score in the TaTME group (P < 0.05; Figure 1).

TaTME and LapTME groups showed no evident differences in Cor, AD, and NE levels three days preoperatively (P > 0.05). Compared with preoperative levels, Cor, AD, and NE levels were elevated statistically in both groups postoperatively, with lower postoperative levels in the TaTME group vs the LapTME group (P < 0.05; Figure 2).

The surgery duration was longer and the intraoperative blood loss was lower in the TaTME group than in the LapTME group (P < 0.05). Moreover, earlier anal exhaust and first postoperative ambulation, faster intestinal recovery, and shorter hospitalization time were noted in the TaTME group (P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Groups | LapTME group (n = 44) | TaTME group (n = 50) | t value | P value |

| Operation time (minute) | 174.95 ± 17.12 | 196.40 ± 21.52 | 5.298 | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 64.59 ± 13.01 | 54.50 ± 9.71 | 4.292 | < 0.001 |

| Anal exhaust time (hour) | 42.89 ± 9.49 | 36.48 ± 11.53 | 2.919 | 0.004 |

| First postoperative ambulation (hour) | 41.34 ± 9.76 | 35.64 ± 9.14 | 2.923 | 0.004 |

| Intestinal recovery time (hour) | 59.84 ± 9.62 | 53.20 ± 7.93 | 23.01 | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalization time (days) | 12.48 ± 3.30 | 9.94 ± 2.39 | 4.309 | < 0.001 |

The distal incisal margin and specimen length were significantly longer in the TaTME group than in the LapTME group

| Groups | LapTME group (n = 44) | TaTME group (n = 50) | t value | P value |

| Distal incisal margin length (cm) | 2.90 ± 0.78 | 3.40 ± 0.57 | 3.577 | < 0.001 |

| Specimen length (mm) | 10.45 ± 2.37 | 12.12 ± 2.27 | 3.486 | < 0.001 |

| Number of lymph nodes cleared (n) | 11.18 ± 3.22 | 11.72 ± 3.26 | 0.806 | 0.422 |

The two groups showed no marked difference in the complication rate (P > 0.05; Table 4).

| Groups | LapTME group (n = 44) | TaTME group (n = 50) | χ2 | P value |

| Anastomotic bleeding | 3 (6.82) | 2 (4.00) | ||

| Anastomotic fistula | 1 (2.27) | 1 (2.00) | ||

| Ileus | 3 (6.82) | 2 (4.00) | ||

| Incision infection | 1 (2.27) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Total occurrence | 8 (18.18) | 5 (10.00) | 1.315 | 0.252 |

The VAS scores were statistically lower in the TaTME group than in the LapTME group at 12, 24, and 36 hours after surgery (P < 0.05; Table 5).

| Groups | LapTME group (n = 44) | TaTME group (n = 50) | t value | P value |

| 12 hours after surgery | 3.91 ± 1.31 | 3.20 ± 1.28 | 2.654 | 0.009 |

| 24 hours after surgery | 3.98 ± 1.30 | 3.18 ± 1.02 | 3.338 | 0.001 |

| 36 hours after surgery | 3.05 ± 1.19 | 2.44 ± 1.25 | 2.414 | 0.012 |

No significant inter-group differences were found in QLQ-C30 scores three days preoperatively (P > 0.05). In the 3rd month postoperatively, the scores of all QLQ-C30 scale dimensions increased significantly, particularly in the TaTME group (P < 0.05; Figure 3).

The treatment outcome of patients with RC largely depends on surgery quality. The treatment principle of radical RC resection is to completely remove the lesion, prevent recurrence, and prolong patient survival[7]. With the development of minimally invasive TME, colorectal surgeons have been exploring local resection for RC. LapTME and TaTME are important minimally invasive TME procedures for LRC; however, their specific efficacy and safety remain controversial.

Although LapTME is currently the preferred treatment option for RC, it may not provide a clearer vision for patients with difficult pelvic conditions[8]. In addition, determining the distal margin of LRC is another difficulty encountered during LapTME. Surgeons usually employ surgical instruments or assistants to perform anal examinations to determine the distal margin, which may result in insufficient or excessive distances from the distal margin[9]. Previous studies have demonstrated that specimen extraction through natural orifices can potentially reduce the incidence of wound-related complications, including postoperative pain and wound infection rates[10]. TaTME is a novel minimally invasive procedure that extracts specimens through natural orifices, allowing for more precise determination of the distal resection edge and making it easier for surgeons to perform deep pelvic anatomy without complex traction[11]. Although the effectiveness of TaTME in treating RC remains controversial[12], several scholars believe that TaTME is a viable and reproducible technique that ensures high-quality tumor resection[13-15]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that TaTME for low and middle RC resulted in high-quality RC resection specimens, lower percentage of cancer-positive margins, shorter hospitalization periods, and lower incidence of anastomotic leakage compared with LapTME[16]. According to another meta-analysis, TaTME achieved surgical outcomes similar to LapTME, with the additional benefits of safe circumferential margins, reduced blood loss, shorter hospitalization periods, reduced referral and readmission rates, and lower postoperative morbidity rates[17]. The results of this study showed that although compared with the LapTME group, the TaTME group had a longer surgery duration, the quality of RC resection specimens was higher and patients had more rapid postoperative recovery. This is similar to the aforementioned studies, further confirming the superiority of TaTME. The reason is that the lower rectum can be dissociated through the anus, thus, allowing for surgery under direct vision and improving the surgical quality, reducing tissue damage, ensuring mesorectum integrity, and facilitating postoperative functional recovery.

Postoperative complications are one of the major factors leading to adverse prognoses in patients undergoing TME for RC. Previous studies have shown that compared with LapTME, TaTME does not have a higher rate of postoperative complications in patients with LRC[9]. Another meta-analysis also revealed no significant difference in the rate of postoperative complications between TaTME and LapTME for LRC treatment[18]. The results of this study showed that the complications caused by TaTME and LapTME were similar, which is consistent with the above-mentioned studies, suggesting a good safety profile of TaTME that provides an additional reference value for its clinical promotion. Surgical trauma can cause systemic stress responses, related to clinical outcomes, such as postoperative complications, activities, and length of hospital stay, in the hypothalamus–pituitary axis of the patients[19,20]. The results of this study showed an obvious elevation in postoperative Cor, AD, and NE levels in the TaTME and LapTME groups, with even lower postoperative levels in the TaTME group. It is suggested that laparoscopic-assisted TaTME induces a milder systemic stress response, which is attributed to the fact that this procedure allows the resected specimen to be removed through the anus, avoiding abdominal incisions and reducing surgical trauma.

This study still shows margins of improvement. First, the long-term clinical outcomes of both groups were not followed up, resulting in the inability to report subsequent recurrence in the patients. Second, this study was conducted in a city hospital with a relatively small number of subjects, so the results obtained may not be representative of the population as a whole. Third, we did not analyze the economic burden associated with TaTME. These shortcomings are expected to be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, TaTME as a treatment option for LRC is safe and can lead to the obtention of high-quality RC resection specimens, stress response level reduction, and postoperative recovery enhancement, advocating for its clinical application.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64542] [Article Influence: 16135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Varela C, Kim NK. Surgical Treatment of Low-Lying Rectal Cancer: Updates. Ann Coloproctol. 2021;37:395-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Serra-Aracil X, Zarate A, Bargalló J, Gonzalez A, Serracant A, Roura J, Delgado S, Mora-López L; Ta-LaTME study Group. Transanal versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for mid and low rectal cancer (Ta-LaTME study): multicentre, randomized, open-label trial. Br J Surg. 2023;110:150-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Khajeh E, Aminizadeh E, Dooghaie Moghadam A, Nikbakhsh R, Goncalves G, Carvalho C, Parvaiz A, Kulu Y, Mehrabi A. Outcomes of Robot-Assisted Surgery in Rectal Cancer Compared with Open and Laparoscopic Surgery. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gang DY, Dong L, DeChun Z, Yichi Z, Ya L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of minimally invasive total mesorectal excision versus transanal total mesorectal excision for mid and low rectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1167200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van der Heijden JAG, Koëter T, Smits LJH, Sietses C, Tuynman JB, Maaskant-Braat AJG, Klarenbeek BR, de Wilt JHW. Functional complaints and quality of life after transanal total mesorectal excision: a meta-analysis. Br J Surg. 2020;107:489-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wilkinson N. Management of Rectal Cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100:615-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Creavin B, Kelly ME, Ryan ÉJ, Ryan OK, Winter DC. Oncological outcomes of laparoscopic versus open rectal cancer resections: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Br J Surg. 2021;108:469-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ren J, Liu S, Luo H, Wang B, Wu F. Comparison of short-term efficacy of transanal total mesorectal excision and laparoscopic total mesorectal excision in low rectal cancer. Asian J Surg. 2021;44:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carmichael H, Sylla P. Evolution of Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020;33:113-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Motson RW, Lacy A. The Rationale for Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:911-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Oostendorp SE, Belgers HJ, Bootsma BT, Hol JC, Belt EJTH, Bleeker W, Den Boer FC, Demirkiran A, Dunker MS, Fabry HFJ, Graaf EJR, Knol JJ, Oosterling SJ, Slooter GD, Sonneveld DJA, Talsma AK, Van Westreenen HL, Kusters M, Hompes R, Bonjer HJ, Sietses C, Tuynman JB. Locoregional recurrences after transanal total mesorectal excision of rectal cancer during implementation. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1211-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Simillis C, Hompes R, Penna M, Rasheed S, Tekkis PP. A systematic review of transanal total mesorectal excision: is this the future of rectal cancer surgery? Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:19-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Deijen CL, Velthuis S, Tsai A, Mavroveli S, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Sietses C, Tuynman JB, Lacy AM, Hanna GB, Bonjer HJ. COLOR III: a multicentre randomised clinical trial comparing transanal TME versus laparoscopic TME for mid and low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3210-3215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Perdawood SK, Kroeigaard J, Eriksen M, Mortensen P. Transanal total mesorectal excision: the Slagelse experience 2013-2019. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:826-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lo Bianco S, Lanzafame K, Piazza CD, Piazza VG, Provenzano D, Piazza D. Total mesorectal excision laparoscopic versus transanal approach for rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;74:103260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lei P, Ruan Y, Yang X, Fang J, Chen T. Trans-anal or trans-abdominal total mesorectal excision? A systematic review and meta-analysis of recent comparative studies on perioperative outcomes and pathological result. Int J Surg. 2018;60:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ren J, Luo H, Liu S, Wang B, Wu F. Short- and mid-term outcomes of transanal versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for low rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2021;100:86-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cuk P, Tiskus M, Möller S, Lambertsen KL, Backer Mogensen C, Festersen Nielsen M, Helligsø P, Gögenur I, Bremholm Ellebæk M. Surgical stress response in robot-assisted versus laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer (SIRIRALS): randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2024;111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Crippa J, Calini G, Santambrogio G, Sassun R, Siracusa C, Maggioni D, Mari G; AIMS Academy Clinical Research Network. ERAS Protocol Applied to Oncological Colorectal Mini-invasive Surgery Reduces the Surgical Stress Response and Improves Long-term Cancer-specific Survival. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2023;33:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |