Published online Sep 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i9.2787

Revised: May 22, 2024

Accepted: July 29, 2024

Published online: September 27, 2024

Processing time: 188 Days and 7.8 Hours

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) is currently a widely accepted method for treating the prolapse of internal hemorrhoids. Postoperative anal stenosis is a critical complication of SH. A remedy for this involves the removal of the circumferential staples of the anastomosis, followed by the creation of a hand-sewn anastomosis. Numerous studies have reported modified SH procedures to improve outcomes. We hypothesized that our modified SH technique may help reduce complications of anal stenosis after SH.

To compare outcomes of staple removal at the 3- and 9-o’clock positions during modified SH in patients with mixed hemorrhoids.

This was a single-center, retrospective, observational study. Patients with grade III or IV hemorrhoids who underwent standard or modified SH at our colorectal center between January 1, 2015, and January 1, 2020, were included. The operation time, blood loss, length of hospital stay, and incidence of minor or major complications were recorded.

Patients with grade III or IV hemorrhoids who underwent standard or modified SH at our colorectal center between January 1, 2015 and January 1, 2020, were included. Operation time, blood loss, length of hospital stay, and incidence of minor or major complications were recorded. We investigated 187 patients (mean age, 50.9 years) who had undergone our modified SH and 313 patients (mean age, 53.0 years) who had undergone standard SH. In the modified SH group, 54% of patients had previously undergone surgical intervention for hemorrhoids, compared with the 40.3% of patients in the standard SH group. The modified SH group included five (2.7%) patients with anal stenosis, while 21 (6.7%) patients in the standard SH group had complications of anal stenosis. There was a significant relationship between the rate of postoperative anal stenosis and the modified SH: 0.251 (0.085-0.741) and 0.211 (0.069-0.641) in multiple regression analysis. The modified SH technique is a safe surgical method for advanced grade hemorrhoids and might result in a lower rate of postoperative anal stenosis than standard SH.

The modified SH technique is a safe surgical method for advanced grade hemorrhoids and might result in a lower rate of postoperative anal stenosis than standard SH.

Core Tip: Postoperative anal stenosis is a critical complication of stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH). In this study, we report our 5-year experience of the outcomes of our modified SH technique. We found that the modified SH method is safe and effective for treating patients with grade III and IV protruding hemorrhoids. The postoperative anal stenosis rate after our modified SH was lower than that after standard SH, particularly among patients who had previously undergone interventions for hemorrhoids.

- Citation: Liu YH, Lin TC, Chen CY, Pu TW. Modified stapled hemorrhoidopexy for lower postoperative stenosis: A five-year experience. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(9): 2787-2795

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i9/2787.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i9.2787

Hemorrhoids are normal cushion structures located in the submucosal layer of the anal canal. It has been estimated that nearly 5% of the general population is affected by anorectal discomfort related to hemorrhoidal disease[1].

Hemorrhoids may be classified as internal, external, or mixed. Patients with hemorrhoids often seek medical advice about bleeding during or after defecation, prolapse, pain associated with hemorrhoidal thrombosis, or itching. Patients with symptomatic hemorrhoids in whom nonoperative treatments have failed may require further intervention or surgery. Conventional surgical hemorrhoidectomy involves excision of hemorrhoidal cushions and is the most effective treatment for hemorrhoids. The interventions include rubber band ligation (RBL), manual anal dilatation, sclerotherapy, cryotherapy, laser hemorrhoidectomy, harmonic ultrasonic scalpel hemorrhoidectomy, and ultrasound-guided hemorr

Milligan-Morgan’s method (open hemorrhoidectomy) and Ferguson’s procedure (closed hemorrhoidectomy) are the most widely applied hemorrhoidectomy procedures worldwide. They have excellent treatment outcomes in terms of hemorrhoidal bleeding and prolapse. Although these techniques are reportedly safe, simple, and cost-effective, they are associated with complications, including postoperative pain, acute urinary retention, and bleeding[4].

To reduce pain and other complications, many studies have investigated the physiology and anatomy of hemorrhoidal disease. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH), a novel procedure, was introduced by Antonio Longo in 1998. This procedure is used for prolapse and hemorrhoids. It does not effectively treat most external hemorrhoids, but it is useful for treating prolapsed internal hemorrhoids. It has been widely accepted because of the absence of external surgical wounds and its association with decreased postoperative pain, bleeding, and urinary retention and faster operative time and return to normal activities. The method involves placing a purse-string suture above the dentate line and subsequently using a stapling device to remove the circumferential column of mucosal and submucosal tissue from the upper anal canal. Finally, SH is completed by resecting any excess mucosa and mucous anastomosis fixed at the rectal wall. The use of this specialized device makes this procedure more expensive.

Nevertheless, short-term complications arising from SH, including anal stenosis, have been well-documented. We developed a modified SH procedure and herein reviewed our 5-year experience with this technique to present a way that may help reduce complications of anal stenosis after SH.

This retrospective study analyzed patients diagnosed with grade III or IV hemorrhoids who underwent surgical treatment (SH) at our colorectal center between January 1, 2015 and January 1, 2020.

We included patients who underwent standard or modified SH for grade III and IV mucosal-hemorrhoidal prolapse, according to the Goligher classification, in this study. Patients who received other interventions (i.e., Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy, hemorrhoidal artery ligation, or stapled transanal rectal resection) or who had grade I or II hemorrhoids were excluded. Patients with hemorrhoidal thrombosis, other anal pathologies (e.g., anal fissure), anal incontinence (continence grading system > 8), or anal stenosis were also excluded. Patients with coagulation disorders or who were on anticoagulation therapy were also not included in this study, as these patients require hemorrhoidectomy with pedicle ligation to control bleeding. Patients who died during follow-up or who refused regular examinations during follow-up were excluded from the study. From 2015 to 2020, 500 patients met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed further.

Preoperative evaluation included clinical and proctological examinations. The following variables were collected during clinical examination: Age, sex, grade of hemorrhoidal disease (by the Goligher classification), previous RBL, regional symptoms, continence disorders, and difficult defecation (e.g., obstructive defecation syndrome or slow-transit consti

Patients underwent the entire procedure under general anesthesia. Prophylactic antibiotics (cefotaxime) were admi

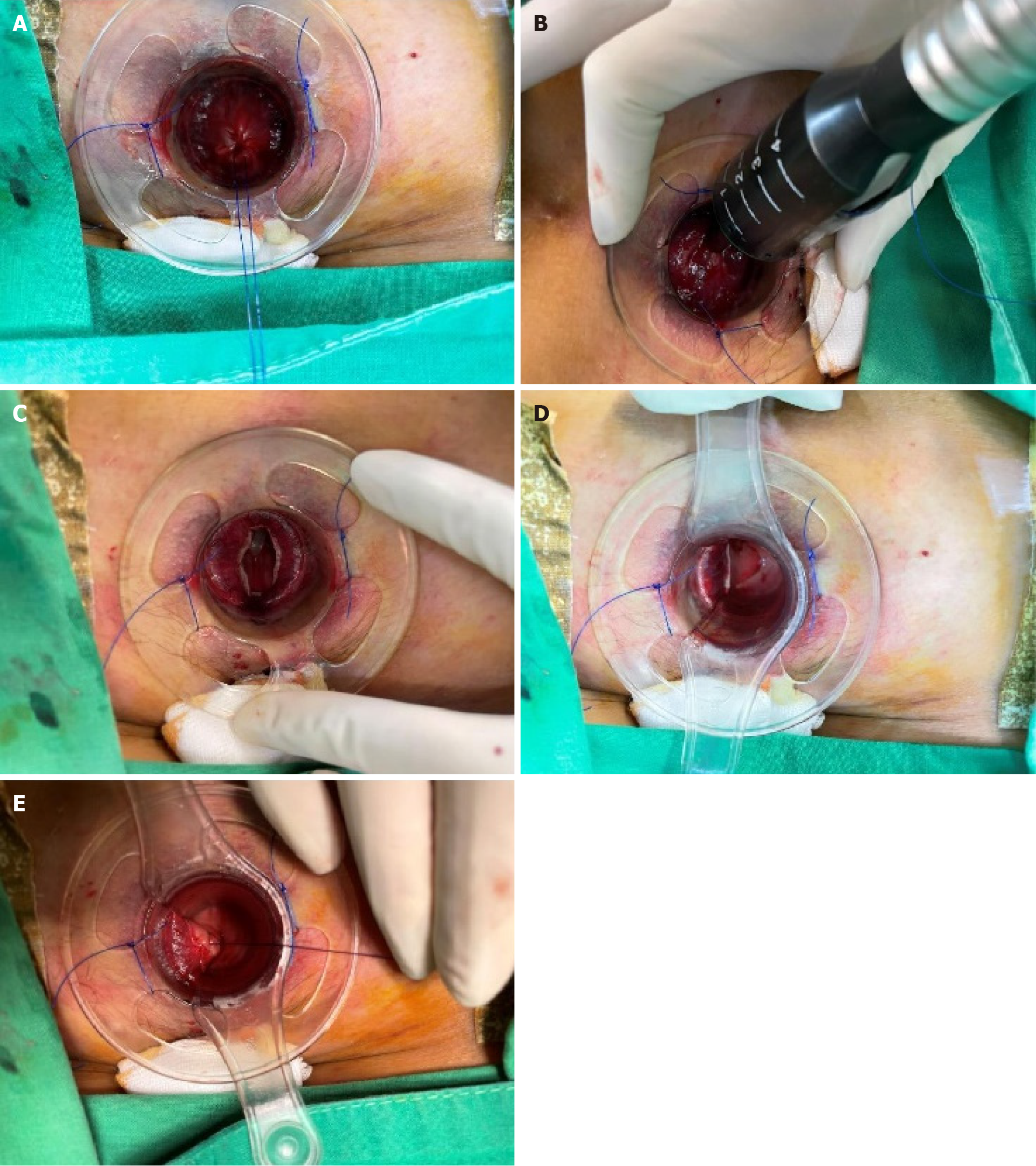

In this study, we performed all surgeries with the hemorrhoidal stapler PPH-03 (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., Pomezia, Italy), which is 33 mm in diameter. After placing the purse-string suture, the stapler was inserted and fired (Figure 1B). For female patients, we confirmed that the vaginal posterior wall was not trapped in the stapler before firing the device.

For standard SH, hemostatic stitching was performed only when bleeding was not stopped by compression with gauze after stapling (Figure 1C). In contrast, in the modified SH, we removed the staples at the 3- and 9-o’clock positions, and hemostatic stitches were preformed if needed (Figures 1D and E). A gauze plug was left in the anal canal postoperatively. All procedures were performed by two proctological surgeons with adequate experience in practice (> 5 years and > 50 SHs per year).

The patients were discharged if they had no difficulty in urination, and those with difficulty in urination were treated with medicine, including painkillers and cholinergic agents. Dysuria within 4 weeks postoperatively was recorded as an intervention requiring urinary catheterization. Patients were followed up at the outpatient clinic 1, 2, and 4 weeks postoperatively. Regular examinations were performed on patient demand, and all patients were recalled 1-year postoperatively for an ultimate evaluation.

For postoperative workup, all patients underwent digital rectal examination and anoscope examination, which was performed both at rest and during straining for better definition of the hemorrhoidal grade by the Goligher classification. Patients who experienced any type of leakage or urge to defecate during the 1-year examination were referred for further evaluation of the anal sphincter. Endoanal ultrasonography was performed when a sphincter lesion was suspected. Those who experienced recurrence underwent Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy and SH.

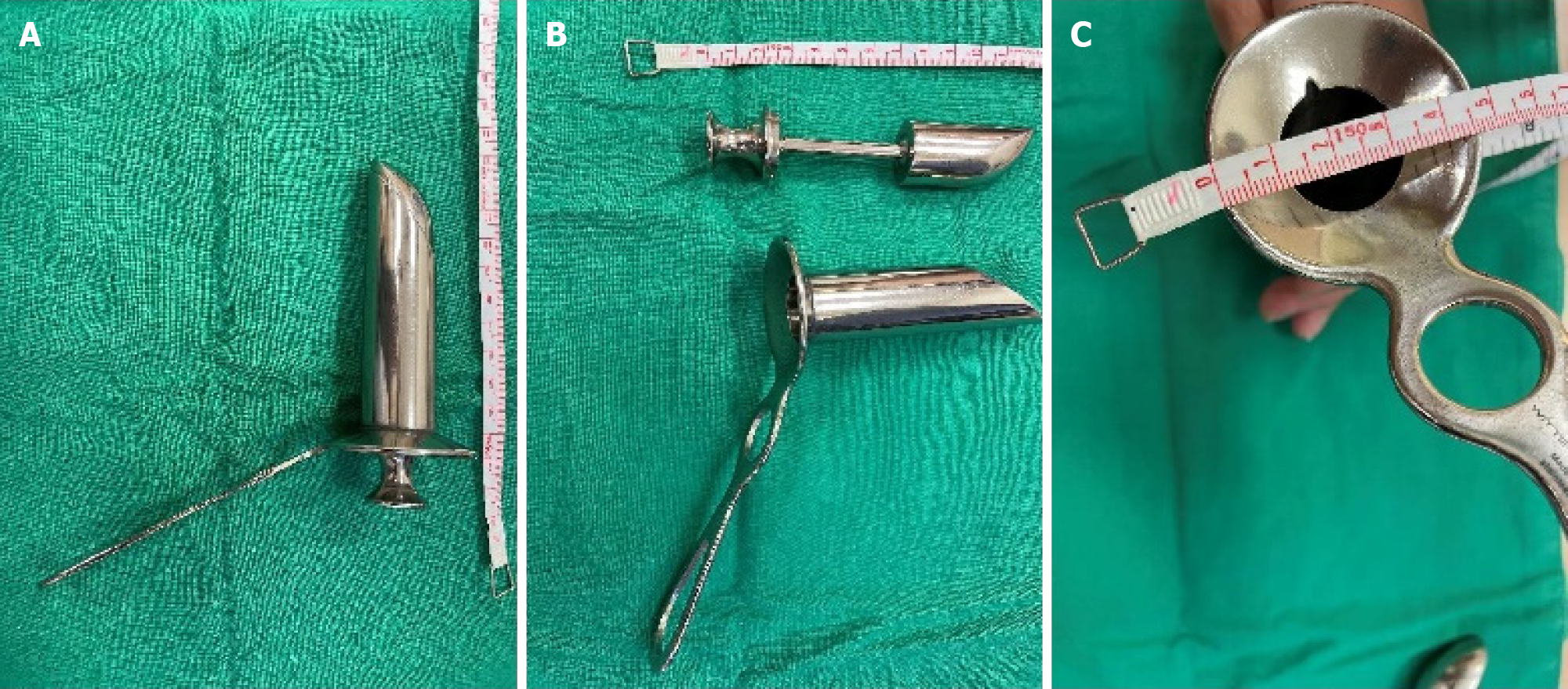

We evaluated preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative parameters. Anal bleeding was defined as any surgical intervention required for hemostasis within 4 weeks postoperatively. Postoperative infection was defined as any episode of infection around the surgical site during the 4-week follow-up. Recurrence was defined as a new hemorrhoid that was at least the same grade as that preoperatively. Symptomatic prolapse was defined as prolapse that caused at least two instances of bleeding, tenesmus, or soiling. In this study, anal stenosis was recorded when it was difficult to perform anoscope examination using a well-lubricated scope (Hirschman anoscope, Figure 2), with difficulty in passing stool during follow-up at the outpatient department. We recorded difficulty in passing stool when patients took more than 30 minutes to defecate and when stools were narrow and broke apart into pellets. For these patients, laxatives and high-fiber diets were prescribed. Further surgical intervention was arranged after failure to dilate the stenosis with an anoscope or to relieve the symptoms at the outpatient department.

All interventions in our study were performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. The need to obtain informed consent was waived by the Taiwan Adventist Hospital Institutional Review Board (protocol number: 110-E-6).

Patient characteristics are summarized as total numbers, percentages, and mean ± SD. The analysis was performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, United States). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

We analyzed 500 patients [183 men (36.6%) and 317 women (63.4%)] who underwent SH for grade III and IV hemorr

| Characteristics | Participants (n = 500) |

| Age (years) | 52.2 ± 13.5 |

| Sex (male) | 183 (36.6) |

| Previous surgery (RBL) | 227 (45.4) |

| Advanced hemorrhoid (grade IV) | 172 (34.4) |

| Operation time (minute) | 17.3 ± 4.0 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 5.3 ± 3.2 |

| Hospital course (day) | 2.3 ± 0.5 |

Patient characteristics, according to the SH group, are shown in Table 2. Of these patients, 227 (45.4%) had undergone hemorrhoidal RBL intervention preoperatively. Non-surgical treatments (e.g., high-fiber diet, adequate fluid intake, probiotics, and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) had been suggested for symptomatic patients.

| Characteristics of study participants | Operation | P value | |

| Modified (n = 187) | Tradition (n = 313) | ||

| Age (years) | 50.9 ± 12.8 | 53.0 ± 13.9 | 0.085 |

| Sex (male) | 77 (41.2) | 106 (33.9) | 0.101 |

| Previous surgery (RBL) | 101 (54.0) | 126 (40.3) | 0.003 |

| Advanced hemorrhoid (grade IV) | 81 (43.3) | 91 (29.1) | 0.001 |

| Operation time (minute) | 18.5 ± 4.2 | 16.6 ± 3.6 | < 0.001 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 4.0 | 0.060 |

| Hospital course (day) | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Complication | |||

| None | 155 (82.9) | 264 (84.3) | 0.669 |

| Bleeding | 4 (2.1) | 7 (2.2) | 0.940 |

| Infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Dysuria | 20 (10.7) | 21 (6.7) | 0.116 |

| Anal stenosis | 5 (2.7) | 21 (6.7) | 0.049 |

| Others | 3 (1.6) | 4 (1.3) | 0.764 |

| Redo surgery | 7 (3.7) | 11 (3.5) | 0.894 |

No dehiscence of the suture line or anal stenosis was noted at discharge. The mean time of discharge from the hospital was 2.3 days ± 0.5 days. The mean blood loss intraoperatively was 5.3 mL ± 3.2 mL, and the mean operative time was 17.3 minutes ± 4.0 minutes.

Grade III or IV mucosal-hemorrhoidal prolapse recurrences developed in 18 patients (3.6%) during the 1-year follow-up. Twelve patients with recurrence underwent redo surgery. Seven of these received Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy, five of them underwent SH again, and six patients refused further surgical intervention.

We found 26 patients (5.2%) with anal stenosis during outpatient department follow-up after SH. Only nine of these underwent transanal stricture release surgery; the others were relieved by finger- or Pratt speculum-based dilation at the outpatient department.

There was a significant difference in the severity of hemorrhoid grade, risk of stenosis, and history of previous surgeries between the groups when comparing standard and modified SH surgeries. In the modified SH group, 81 (43.3%) patients had grade IV hemorrhoids, while 101 (54.0%) patients had undergone RBL previously. In contrast, the traditional group had 91 (29.1%) patients with advanced hemorrhoids and 126 (40.3%) patients had undergone previous anal surgery.

We found a longer operation time, but a shorter hospital stay, in the modified SH group, although the differences between the two groups were small: 1.9 minutes longer operation time and 0.2-day shorter hospital stay in the modified than in the standard SH group.

Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the anal stenosis rate postoperatively between the groups. The modified SH group included five (2.7%) patients with anal stenosis, while 21 (6.7%) patients in the standard SH group had complications of anal stenosis.

A study found that the best predictive factor for post-SH anal stenosis was the experience of prior surgical intervention in the anus[4]. In our study, we also noted higher post-SH anal stenosis rates among those with previous surgery, RBL, compared to those without such experience (Table 3): Odds ratio = 3.082 (1.314-7.230). Moreover, we found modified SH group with prominent relation to post-SH anal stenosis: Odds ratio = 0.251 (0.085-0.741). There is a significant relation

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P value | Multiple regreaion, OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Sex | 0.920 (0.408-2.071) | 0.840 | - | - |

| Age | 1.030 (1.001-1.059) | 0.041a | 1.024 (0.995-1.054) | 0.099 |

| Previous surgery (RBL) | 3.082 (1.314-7.230) | 0.010a | 3.597 (1.506-8.590) | 0.004a |

| Severity (grade IV) | 0.840 (0.358-1.974) | 0.840 | - | - |

| Modified SH | 0.251 (0.085-0.741) | 0.012a | 0.211 (0.069-0.641) | 0.006a |

Herein, we presented a modified SH technique, involving staple removal at the 3- and 9-o’clock positions, to reduce the incidence of anal stenosis without other significant complications. The odds ratio between postoperative anal stenosis rate and modified SH were 0.251 (0.085-0.741) and 0.211 (0.069-0.641) in the multiple regression analysis, respectively.

Hemorrhoids are rarely life-threatening; however, there are many possible postoperative complications. By under

SH is currently widely accepted and has become a prominent method for treating the prolapse of internal hemorrhoids. This method is useful as it alleviates postoperative pain, has a shorter operation duration and hospital stay, and earlier recovery compared to conventional hemorrhoidectomy[6]. However, a recent meta-analysis of 1343 patients revealed higher recurrence rates and reoperation risks from SH compared to conventional surgery in the long term[7]. Bellio et al[8] reported that the recurrence rate was as high as 39% in the 10 years after SH, which was slightly higher than that reported in other studies, because of different classifications of recurrence. Conversely, another study demonstrated a 14.7% reoperation rate for recurrence[9]. In our experience, the overall recurrence rate for grade III and IV mucosal-hemorrhoidal prolapse was 3.6%. In this study, 55 patients (10.9%) underwent redo surgeries, but the rate of grade III and IV recurrence among those who underwent redo surgery was only 3.6% (n = 18), which included seven patients who underwent modified SH and 11 patients who underwent standard SH. Although the rate of our redo surgery was similar to that in other studies, to investigate the main influencing factors thoroughly, we included anoplasty, a check for bleeding, standard SH, Ferguson’s hemorrhoidectomy, and RBL as redo surgery cases. The proportion of patients who underwent redo surgery due to grade III and IV hemorrhoid recurrence was not markedly high.

Previous studies have reported that patients who underwent standard SH presented with some early complications, including bleeding and urinary retention, and could be treated during hospitalization; however, long-term outcomes of SH, particularly the prevalence of anal stenosis and recurrent prolapse, are insufficiently considered[10]. Stenosis is a rare, long-term complication of SH. An incidence of less than 5% has been recorded, and it occurs at an average time of 125 days ± 5 postoperatively. This may be caused by removing disproportionate tissue without leaving mucosal bridges between the surgical wounds around the anal canal, causing over-scarring and stricture formation[11,12]. According to Petersen et al[11], those who exhibited post-SH stenosis were detected within 100 days, in agreement with our experience. Of the 26 patients (5.2%) with anal stenosis after SH in our study, only 9 (1.8%) required further surgical intervention. These 9 patients were all from the standard SH group and underwent trans-anal release of the 3- and 9-o’clock strictures, with hemostatic stitches performed if needed. To address these complications, we modified the SH by releasing the 3- and 9-o’clock staples during the modified SH surgery, to prevent anal stenosis.

Most stenoses lack clinical relevance. A possible predictive factor for stenosis is previous interventions for hemorrhoids and severe postoperative pain[11]. Anal stenosis is not a specific problem of SH but is an onerous burden for patients after undergoing anal interventions.

There is no well-known mechanism for anal stenosis after SH. One potential theory is ring dehiscence, which may be a consequence of submucous inflammation[13]. Others have proposed that the cause could be an inappropriate depth of the staples, which stimulated the squamous skin cells to scar, and which subsequently shrunk[14]. This plausible mechanism could explain the risk factor of severe postoperative pain: The staple ring in the anal canal may be the cause of severe pain. Therefore, removal of the stenotic anastomosis and remaining staples seems to be a reasonable treatment option for complications after SH.

Agraffectomy was reported as an operation that involves removing the circumferential staples of the anastomosis, followed by creating a hand-sewn anastomosis to alleviate pain in post-SH syndrome, and is performed particularly for patients with postoperative pain and stenosis[15]. For a better outcome of SH, Yu et al[16] provided a technique of placing a large C suture and inserting a brain spatula before firing surgical staples, which could reduce anastomotic stenosis in a simple and effective way. Lin et al[17,18] developed a new device for partial SH, which could also reduce the post

Based on the procedures that dealt with complications, we modified our strategy so that these patients received further anoplasty with the trans-anal release of the stricture, removal of the staples at the 3- and 9-o’clock positions, and the subsequent refashioning of the anastomosis (regardless of whether there was mild or severe stenosis). Similar viewpoints about partial SH have been discussed for many years. Fewer staples are used to preserve the mucosal bridges and to reduce the risk for some of the complications (e.g., anastomotic stenosis, rectovaginal fistula, and defecatory dysfunction) as compared with conventional circumferential SH[19]. A recent study by Lin et al[17] demonstrated that partial SH was associated with reduced postoperative pain and urgency, better postoperative anal continence, and a minimal risk of rectal stenosis. From the studies above, our modified SH technique might help prevent post-anal surgery-related anal stenosis.

Despite the strengths of our study, the present study had several limitations. First, we enrolled 500 cases over the course of 5 years, which produced a small sample size. Our study involved a single center and did not have a control group, which might have caused an unidentified bias. Additionally, the follow-up period was short, and many complications may not yet have occurred at the time of the last follow-up, leading to an underestimation of complications among patients. Second, information on important confounders of the associated risks (e.g., family history, obesity, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, dietary patterns, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and many other comorbidities) were not well recorded, and the confounding effect may thus only be partially excluded. Third, we did not mention cost-effectiveness, because our hospital is situated at the center of Taipei, Taiwan, which serves a relatively small but well-populated area with a higher level of income. Furthermore, large-scale prospective studies are needed to investigate these results and to compare different treatments for prolapsed hemorrhoids.

In this study, the modified SH was found to be an effective and safe surgical method for treating patients with grade III and IV protruding hemorrhoids. The rate of postoperative anal stenosis with this approach was lower than that of standard SH, even among patients who had undergone previous interventions for hemorrhoids. Modified SH is safe, with many short-term benefits. However, the long-term outcomes should be further investigated.

The authors are grateful to the Taiwan Adventist Hospital for support in the recruitment of study participants and fulfillment of all examination.

| 1. | Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation. An epidemiologic study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:380-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Clinical Practice Committee; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1461-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Cerato MM, Cerato NL, Passos P, Treigue A, Damin DC. Surgical treatment of hemorrhoids: a critical appraisal of the current options. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2014;27:66-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Agbo SP. Surgical management of hemorrhoids. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2011;3:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sneider EB, Maykel JA. Diagnosis and management of symptomatic hemorrhoids. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:17-32, Table of Contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ganio E, Altomare DF, Gabrielli F, Milito G, Canuti S. Prospective randomized multicentre trial comparing stapled with open haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang GQ, Liu Y, Liu Q, Yang RQ, Hong W, Fan K, Lu M. [A meta-analysis on short and long term efficacy and safety of procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2013;51:1034-1038. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bellio G, Pasquali A, Schiano di Visconte M. Stapled Hemorrhoidopexy: Results at 10-Year Follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:491-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Raahave D, Jepsen LV, Pedersen IK. Primary and repeated stapled hemorrhoidopexy for prolapsing hemorrhoids: follow-up to five years. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:334-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Avgoustou C, Belegris C, Papazoglou A, Kotsalis G, Penlidis P. Evaluation of stapled hemorrhoidopexy for hemorrhoidal disease: 14-year experience from 800 cases. Minerva Chir. 2014;69:155-166. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Petersen S, Hellmich G, Schumann D, Schuster A, Ludwig K. Early rectal stenosis following stapled rectal mucosectomy for hemorrhoids. BMC Surg. 2004;4:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fazio VW. Early promise of stapling technique for haemorrhoidectomy. Lancet. 2000;355:768-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fueglistaler P, Guenin MO, Montali I, Kern B, Peterli R, von Flüe M, Ackermann C. Long-term results after stapled hemorrhoidopexy: high patient satisfaction despite frequent postoperative symptoms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:204-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Burke ER, Welvaart K. Complications of stapled anastomoses in anterior resection for rectal carcinoma: colorectal anastomosis versus coloanal anastomosis. J Surg Oncol. 1990;45:180-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Petersen S, Jongen J, Schwenk W. Agraffectomy after low rectal stapling procedures for hemorrhoids and rectocele. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yu JH, Huang XW, Wu ZJ, Lin HZ, Zheng FW. Clinical study of use of large C suture in procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids for treatment of mixed hemorrhoids. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060521997325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lin HC, He QL, Shao WJ, Chen XL, Peng H, Xie SK, Wang XX, Ren DL. Partial Stapled Hemorrhoidopexy Versus Circumferential Stapled Hemorrhoidopexy for Grade III to IV Prolapsing Hemorrhoids: A Randomized, Noninferiority Trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:223-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lin HC, He QL, Ren DL, Peng H, Xie SK, Su D, Wang XX. Partial stapled hemorrhoidopexy: a minimally invasive technique for hemorrhoids. Surg Today. 2012;42:868-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jeong H, Hwang S, Ryu KO, Lim J, Kim HT, Yu HM, Yoon J, Lee JY, Kim HR, Choi YG. Early Experience With a Partial Stapled Hemorrhoidopexy for Treating Patients With Grades III-IV Prolapsing Hemorrhoids. Ann Coloproctol. 2017;33:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |