Published online Jul 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2343

Revised: May 23, 2024

Accepted: June 12, 2024

Published online: July 27, 2024

Processing time: 106 Days and 21.1 Hours

Chylous ascites is caused by disruption of the lymphatic system, which is characterized by the accumulation of a turbid fluid containing high levels of triglycerides within the abdominal cavity. The two most common causes are cirrhosis and tuberculosis, and colon signer ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) due to the use of immunosuppressants is extremely rare in cirrhotic patients after liver transplan

A 52-year-old man who underwent liver transplantation and was administered with immunosuppressants for 8 months was admitted with a 3-month history of progressive abdominal distention. Initially, based on lymphoscintigraphy and lymphangiography, lymphatic obstruction was considered, and cystellar chyli decompression with band lysis and external membrane stripping of the lymphatic duct was performed. However, his abdominal distention was persistent without resolution. Abdominal paracentesis revealed allogenic cells in the ascites, and immunohistochemistry analysis revealed adenocarcinoma cells with phenotypic features suggestive of a gastrointestinal origin. Gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed, and biopsy showed atypical signet ring cells in the ileocecal valve. The patient eventually died after a three-month follow-up due to progression of the tumor.

Colon SRCC, caused by immunosuppressants, is an unusual but un-neglected cause of chylous ascites.

Core Tip: Chylous ascites can be caused by various etiologies, among which cirrhosis, malignancy and tuberculosis are the most common. However, colon signer ring cell carcinoma secondary to use of immunosuppressants is rare in cirrhotic patients after liver transplantation, and these patients are easily prone to misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis. We report a case of chylous ascites caused by colon signer ring cell carcinoma due to the use of immunosuppressants after liver trans

- Citation: Li Y, Tai Y, Wu H. Colon signet-ring cell carcinoma with chylous ascites caused by immunosuppressants following liver transplantation: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(7): 2343-2350

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i7/2343.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2343

Chylous ascites is caused by disruption of the lymphatic system due to traumatic injury or obstruction, leading to extravasation of thoracic or intestinal lymph into the abdominal cavity and the accumulation of a milky fluid rich in triglycerides[1]. The pathophysiologic mechanisms of chylous ascites mainly include acquired lymphatic disruption, fibrosis of the lymphatic system and congenital causes[2]. Cirrhosis and malignancy are the most common causes of chylous ascites in Western countries, and infections such as tuberculosis and filariasis are the major causes of chylous ascites in Eastern and developing countries[3]. Cases of chylous ascites as the primary manifestation caused by colon signer ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) due to the use of immunosuppressants in cirrhotic patients after liver transplantation are rare, and there are no reported cases to date.

Liver transplantation has become the therapy of choice for various acute and chronic end-stage liver diseases, and immunosuppressants are used to inhibit immune cell proliferation and reduce immune attack against grafts[4]. Liver transplantation-induced immunological rejection has steadily improved over the years[5]. However, the life-long use of immunosuppressants after liver transplantation can lead to an increased risk of malignancy, which is two to four times greater than that in the healthy population[6]. Herein, for the first time, we report a case of chylous ascites caused by colon SRCC due to the use of immunosuppressants after liver transplantation in a 52-year-old man. Given the lack of reported cases on the use of immunosuppressants after liver transplantation leading to malignancy mainly manifesting as chylous ascites, we reviewed previously reported cases of malignancy development due to the use of immunosuppressants after liver transplantation.

A 52-year-old Chinese man presented with progressive abdominal distention for 3 months.

Symptoms started 3 months before presentation with recurrent abdominal distention. No definite diagnosis was made after an examination at a local hospital, and the patient was transferred to our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment.

Four years previously, the patient presented to a local hospital with a complaint of jaundice, and alcoholic cirrhosis was diagnosed. Eight months prior to presentation, he underwent orthotopic liver transplantation, after which sirolimus and mycophenol sodium were administered for immunosuppressive treatment.

The patient denied a history of tuberculosis, parasites such as filaments, cardiovascular disease, trauma or surgery other than liver transplantation. His father, who did not live with him, was diagnosed with tuberculosis and achieved a cure after regular anti-tuberculosis treatment 9 years ago.

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 37.8 ℃; blood pressure, 97/64 mmHg; heart rate, 127 per minute; and respiratory rate, 22 per minute. A spider angioma was observed, and a horizontal hernia scar was visible on the abdomen, without tenderness or rebound tenderness. The liver was palpable 3 cm beneath the rib cage.

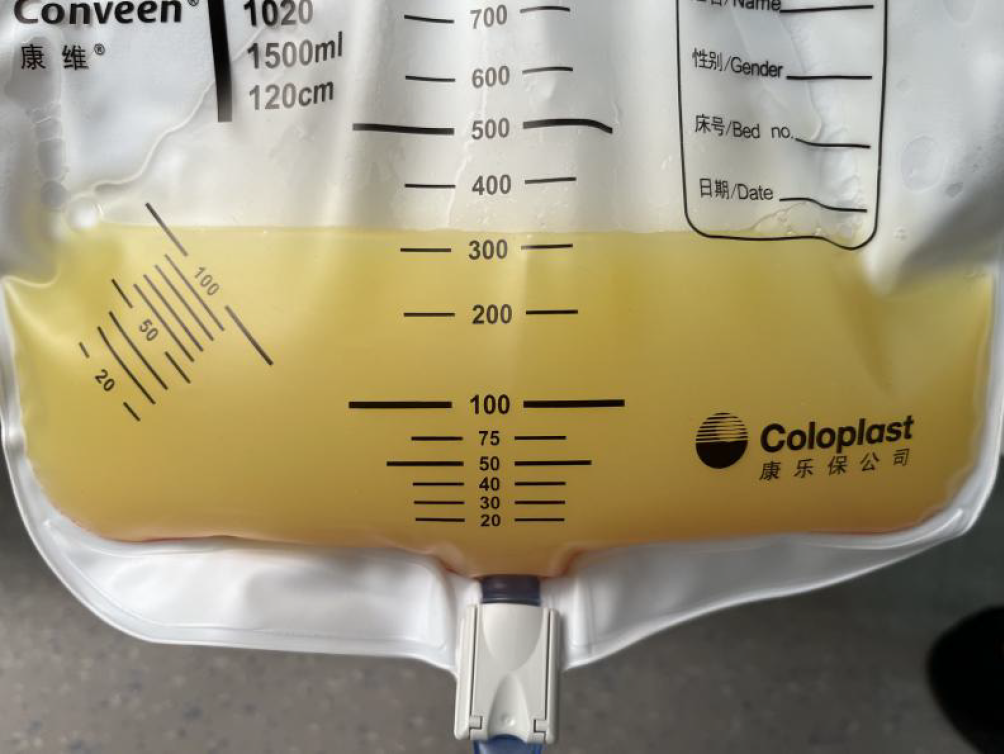

A complete blood count indicated decreased hemoglobin (11.3 g/dL) and leukocyte (2.74 × 103/μL) levels, normal platelet counts and aminotransferase and total bilirubin levels, decreased albumin (30.3 g/L) and globulin (15.8 g/L) levels, and normal prothrombin time. The abdominal puncture fluid was chylous (Figure 1), and ascites tests revealed elevated karyocyte (690 × 106/L), mononuclear cell (41%), and pleocyte (59%) counts and a serum ascites albumin gradient < 11 g/L. Alogenic cells were found, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis suggested that the patient was positive for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX2). The tuberculosis DNA, tuberculosis X-pert and Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture results of the ascites fluid were negative. Infection markers and immune-related indicators were negative. Blood CEA and alpha-fetoprotein mass concentration were within the normal range, and blood CA199 mass concentration (31.79 U/mL) was increased.

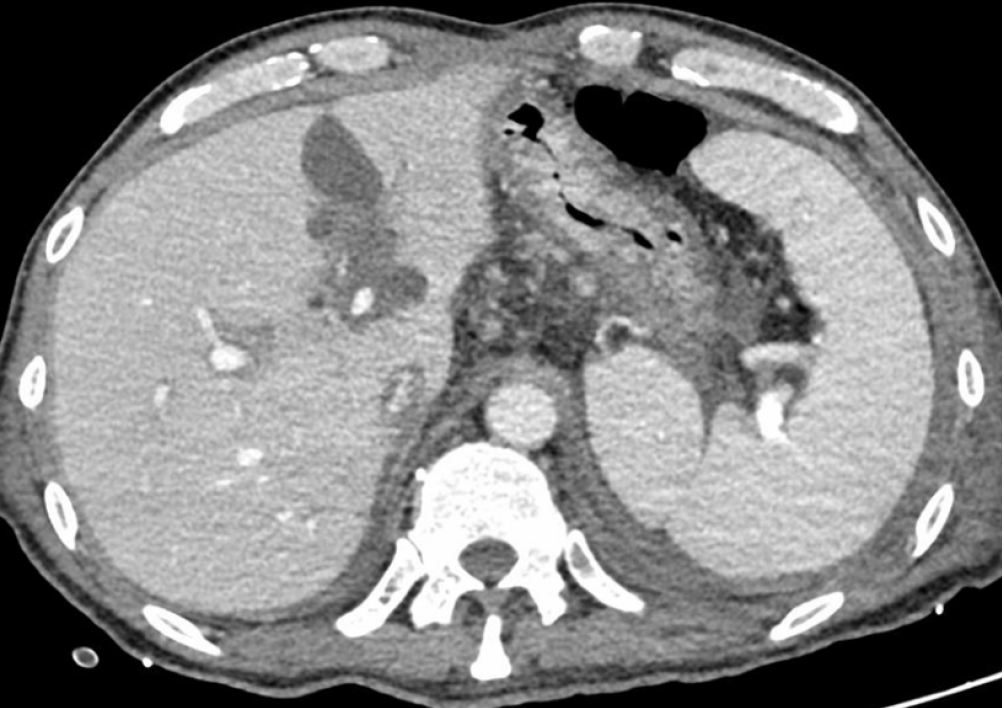

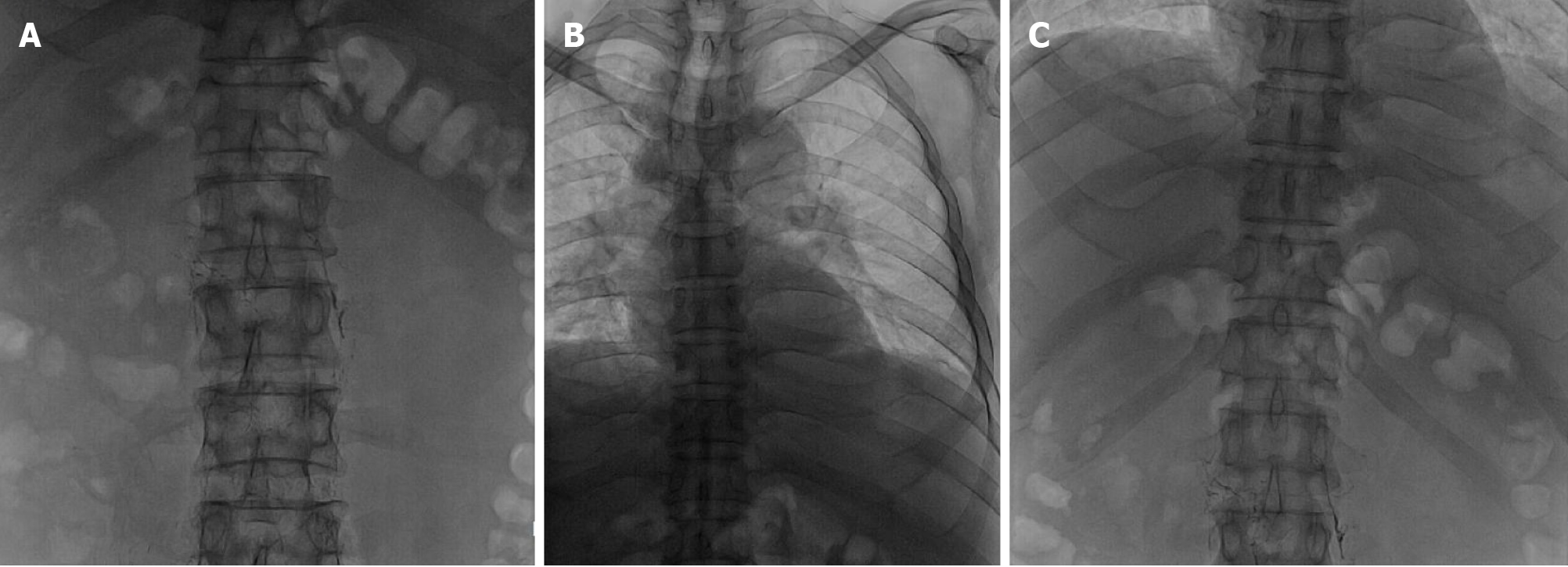

Local hospital neck vein ultrasound revealed thrombus formation in the near-heart segment of the right subclavian vein. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography suggested ascites, and the liver lymphatic vessels were dilated (Figure 2). Lymphoscintigraphy suggested that slow lymph flow in the lower extremities, abdomen and pelvic regions was associated with diffuse and uneven increases in radioactivity distribution (Figure 3). Lymphangiography revealed lymphatic drainage obstruction above the L3 level (Figure 4).

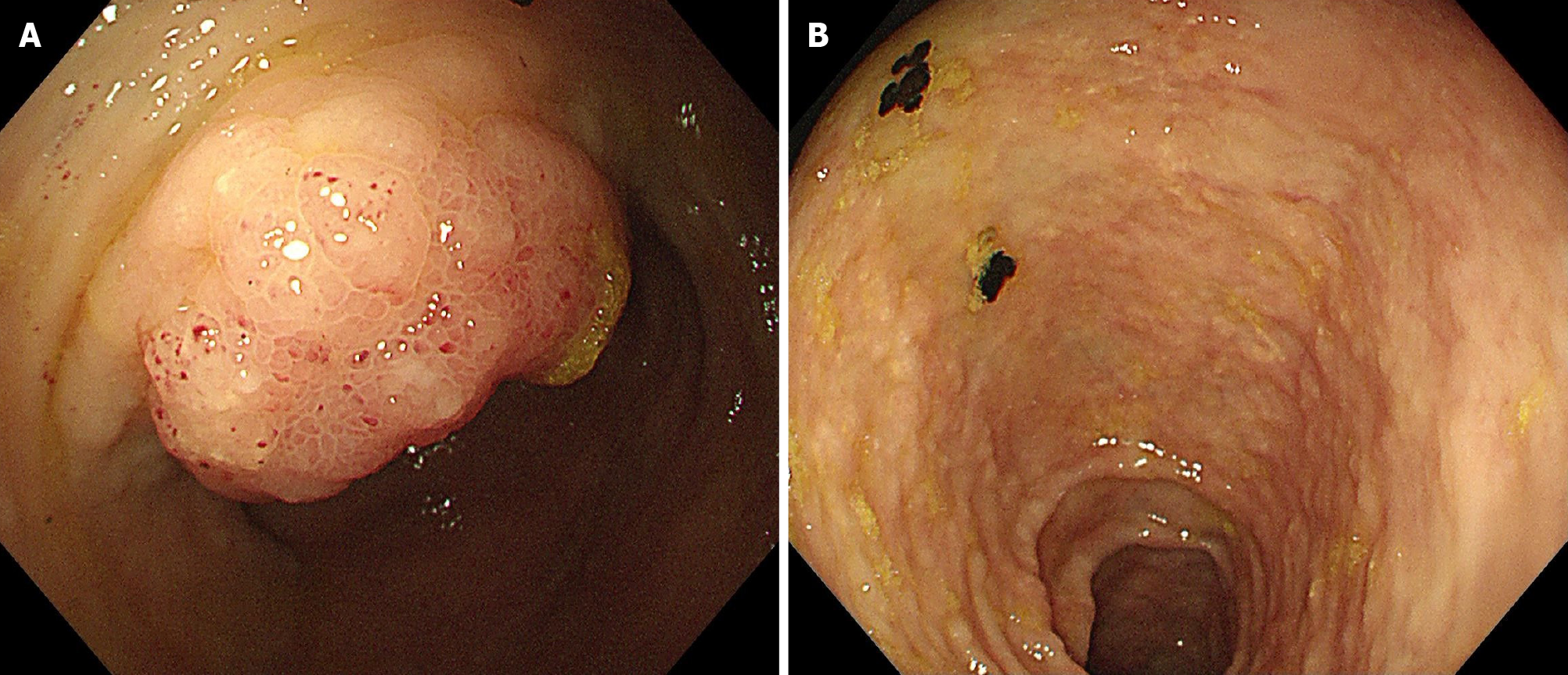

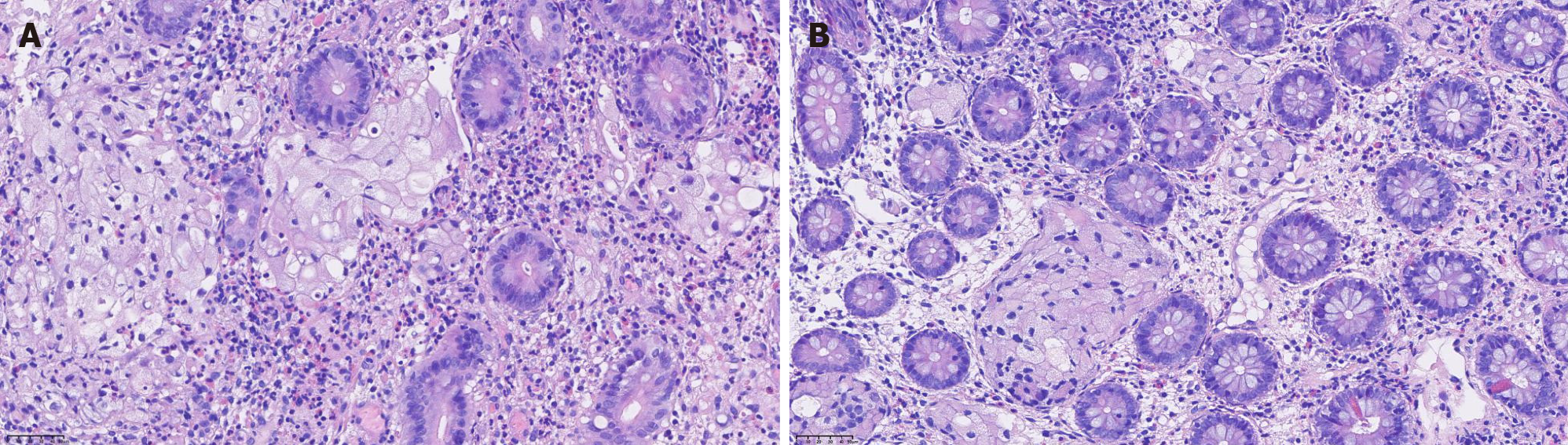

Lymphoscintigraphy and lymphangiography revealed lymphatic obstruction, and combined with the patient’s past medical history, the basis of the carcinoma was subsequently evaluated. Positron emission tomography suggested metastatic changes in the lymph nodes behind the abdominal cavity and inferior vena cava, allogenic cells were identified in the abdominal puncture fluid, and IHC analysis suggested that CEA and CDX2 were positive. Thus, gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed and found widespread white mucosa in the corpora ventriculi and sinuses ventriculi, edema of the mucosa in the ileocecal region and granular changes in the colon (Figure 5). Biopsy revealed atypical signet ring cells in the ileocecal valve (Figure 6), and IHC analysis revealed that MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, E-cadherin, CK (Pan), and CK20 were positively expressed, while p53 and CDX2 were partially expressed.

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was lymph node metastasis of colon SRCC, resulting in lymphatic obstruction.

Sirolimus was reduced and mycophenol sodium was discontinued, with the use of a high-protein, low-fat, medium-chain triglyceride (MCT)-based diet and total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Abdominal distension was relieved primarily by employing abdominal drainage.

Regrettably, the patient died due to progression of the tumor after three months of follow-up.

Chylous ascites is caused by disruption of the lymphatic system due to multiple etiologies, such as malignancy, cirrhosis, trauma, autoimmunity, and inflammation[7]. According to the data from Press et al[8] published in 1984, approximately 1 per 20 000 people suffer from chylous ascites, most of which are caused by malignancies. Among the malignancies, lymphoma was the most common, accounting for more than two-thirds of the cases, and other carcinomas included pancreatic (2/24), breast (2/24), colon (1/24), prostate (1/24), ovarian (1/24), and hypernephroma (1/24). However, subsequent to that time period, no further epidemiological studies have been carried out; thus, the current incidence remains unclear. Abdominal paracentesis is required to evaluate, diagnose and manage patients with ascites if the ascites are turbid and the triglyceride concentration is above 200 mg/dL, which indicates a diagnosis of chylous ascites, while a level less than 50 mg/dL excludes it[3].

With improvements in surgery and reductions in graft rejection, liver transplantation has become the definitive therapy for most types of end-stage liver disease[9]. However, complications caused by immunosuppression, especially malignancy, have been considered major limitations[10]. The pathophysiology of immunosuppressants leading to malignancies is complex and is associated with multiple risk factors such as loss of immunosurveillance, derangement of molecular signaling/DNA repair mechanisms and decreased antiviral immune activity[10]. In a state of immunocompetence, the immune system functions to surveil and suppress the growth and multiplication of neoplastic cells[11]. However, immunosuppressants such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine exert their effects through interaction and functional suppression of calcineurin, which inhibits interleukin-2 synthesis and T-cell activation[12]. In addition, they upregulate vascular endothelial growth factor expression and increase the expression of growth factor-beta 1, both of which contribute to cancer cell growth promotion via angiogenesis facilitation, cancer cell invasion, and metastasis[13]. Moreover, viruses may induce tumor formation through either direct genetic manipulation or interactions with cellular oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Immunosuppressive agents have emerged as important contributors to viral oncogenesis, as they increase the incidence of infections and facilitate the growth of cancer cells[14]. Finally, more intense immunosuppression can not only increase the incidence of malignancy but also promote more aggressive neoplasm progression, characterized by rapid growth and metastasis[15].

Given the rarity of chylous ascites caused by colon SRCC due to the use of immunosuppressants after liver transplantation, we searched PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) for English-language case reports describing carcinoma caused by the use of immunosuppressants after liver transplantation published between 1984 and 2023. The following medical terms were used: (1) ‘Cancer’, ‘neoplasm’ or ‘malignancy’; (2) ‘Immunosuppressants’, ‘Immunosuppressive Agents’; (3) ‘Liver Grafting’, ‘Liver Transplantation’, ‘Hepatic Transplantation’; and (4) ‘Case Reports’, ‘Case Study’, ‘Case Histories’. Initially, we collected a total of 217 case reports. After excluding reports with missing data on patient outcomes, we screened out approximately 43 valid cases, the results of which are summarized in the Supplementary Table 1. Nearly 50% of malignancies are found in the hematological system, which may be related to damage to lymphatic tissue caused by impaired immune function in the body. There was no significant difference in the occurrence between males and females, and the primary treatment options included changing the immunosuppressants, reducing the dosage, or administering radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

For the patient, both abdominal enhanced computed tomography and lymphangiography suggested lymphatic obstruction, and we further examined the relative etiologies of lymphatic obstruction. Positron emission tomography suggested metastatic changes in the lymph nodes behind the abdominal cavity and inferior vena cava. In addition, we identified allogenic cells in the abdominal puncture fluid, and IHC analysis suggested that CEA and CDX2 were positive. Thus we further searched for tumor evidence and performed gastrointestinal endoscopy. Biopsy of the ileocecal valve revealed the presence of atypical signet ring cells. Colon SRCC, caused by the use of immunosuppressants, is a rare cause of chylous ascites in cirrhotic patients after liver transplantation. Several studies have reported different incidence rates, approximately 1%-7%, for this cause of chylous ascites, which is associated with high mortality[8,16]. Although colon SRCC has been reported to possibly occur secondary to immunosuppression following liver transplantation, the presence of chylous ascites as a prominent clinical presentation has not been well documented due to its rarity. For the first time, we report an extremely rare and easily overlooked cause of chylous ascites in which the use of immunosuppressants after liver transplantation in patients with cirrhosis led to the occurrence of colon SRCC, which in turn blocked lymphatic vessels.

In clinical practice, it is crucial for physicians to consider the comprehensive etiology of chylous ascites, especially in patients with a history of immunosuppressive agent use, and evaluate whether it is associated with neoplastic processes. Press et al[8] recommended that patients with cirrhosis and unnecessary, expensive and invasive diagnostic modalities be avoided to exclude malignant processes unless there is a strong suspicion of malignancy. However, chylous ascites resulting from carcinoma should be considered when patients exhibit unexplained systemic symptoms. Moreover, treatment options for chylous ascites caused by colon SRCC due to the use of immunosuppressants after liver trans

However, a limitation of this study is that the patient did not undergo a colonoscopy prior to liver transplantation. As a result, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that immunosuppressants may have contributed to tumor deve

The use of immunosuppressants, which can lead to colon SRCC, is an unusual cause of chylous ascites in cirrhotic patients after liver transplantation. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography and lymphangiography provide valuable evidence for identifying the cause of chylous ascites due to lymphatic obstruction, and biopsy is crucial for both diagnosis and differential diagnosis. However, further studies with larger sample sizes are indispensable for investigating the morbidity and natural course of these tumors due to the use of immunosuppressants after liver trans

| 1. | Lizaola B, Bonder A, Trivedi HD, Tapper EB, Cardenas A. Review article: the diagnostic approach and current management of chylous ascites. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:816-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Browse NL, Wilson NM, Russo F, al-Hassan H, Allen DR. Aetiology and treatment of chylous ascites. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1145-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cárdenas A, Chopra S. Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1896-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5110] [Cited by in RCA: 5313] [Article Influence: 183.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dhanasekaran R. Management of Immunosuppression in Liver Transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:337-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Herrero JI. Screening of de novo tumors after liver transplantation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1011-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Evans JG, Spiess PE, Kamat AM, Wood CG, Hernandez M, Pettaway CA, Dinney CP, Pisters LL. Chylous ascites after post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: review of the M. D. Anderson experience. J Urol. 2006;176:1463-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Press OW, Press NO, Kaufman SD. Evaluation and management of chylous ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zarrinpar A, Busuttil RW. Liver transplantation: past, present and future. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:434-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Nair N, Gongora E, Mehra MR. Long-term immunosuppression and malignancy in thoracic transplantation: where is the balance? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:461-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Krisl JC, Doan VP. Chemotherapy and Transplantation: The Role of Immunosuppression in Malignancy and a Review of Antineoplastic Agents in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1974-1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Billups K, Neal J, Salyer J. Immunosuppressant-driven de novo malignant neoplasms after solid-organ transplant. Prog Transplant. 2015;25:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Campistol JM, Cuervas-Mons V, Manito N, Almenar L, Arias M, Casafont F, Del Castillo D, Crespo-Leiro MG, Delgado JF, Herrero JI, Jara P, Morales JM, Navarro M, Oppenheimer F, Prieto M, Pulpón LA, Rimola A, Román A, Serón D, Ussetti P; ATOS Working Group. New concepts and best practices for management of pre- and post-transplantation cancer. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2012;26:261-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Herrera LA, Benítez-Bribiesca L, Mohar A, Ostrosky-Wegman P. Role of infectious diseases in human carcinogenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45:284-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yokoyama I, Carr B, Saitsu H, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Accelerated growth rates of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Cancer. 1991;68:2095-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baniel J, Foster RS, Rowland RG, Bihrle R, Donohue JP. Complications of post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. J Urol. 1995;153:976-980. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Pageaux GP, Calmus Y, Boillot O, Ducerf C, Vanlemmens C, Boudjema K, Samuel D; French CHI-F-01 Study Group. Steroid withdrawal at day 14 after liver transplantation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1454-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Manzia TM, Angelico R, Gazia C, Lenci I, Milana M, Ademoyero OT, Pedini D, Toti L, Spada M, Tisone G, Baiocchi L. De novo malignancies after liver transplantation: The effect of immunosuppression-personal data and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5356-5375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Padbury RT, Gunson BK, Dousset B, Hubscher SG, Buckels JA, Neuberger JM, Elias E, McMaster P. Steroid withdrawal from long-term immunosuppression in liver allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1993;55:789-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |