Published online Jul 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2242

Revised: May 16, 2024

Accepted: June 3, 2024

Published online: July 27, 2024

Processing time: 143 Days and 21.8 Hours

The high incidence and mortality of gastric cancer (GC) pose a significant threat to human life and health, and it has become an important public health challenge in China. Body weight loss is a common complication after surgical treatment in patients with GC and is associated with poor prognosis and GC recurrence. However, current attention to postoperative weight change in GC patients remains insufficient, and the descriptions of postoperative weight change and its influencing factors are also different.

To investigate body weight changes in patients with GC within 6 mo after gastrectomy and identify factors that influence dynamic body weight changes.

We conducted a prospective longitudinal study of 121 patients with GC and collected data before (T0) and 1 (T1), 3 (T2), and 6 (T3) mo after gastrectomy using a general data questionnaire, psychological distress thermometer, and body weight measurements. The general estimation equation (GEE) was used to analyze the dynamic trends of body weight changes and factors that influence body weight changes in patients with GC within 6 mo of gastrectomy.

The median weight loss at T1, T2, and T3 was 7.29% (2.84%, 9.40%), 11.11% (7.64%, 14.91%), and 14.75% (8.80%, 19.84%), respectively. The GEE results showed that preoperative body mass index (BMI), significant psychological distress, religious beliefs, and sex were risk factors for weight loss in patients with GC within 6 mo after gastrectomy (P < 0.05). Compared with preoperative low-weight patients, preoperative obese patients were more likely to have weight loss (β = 14.685, P < 0.001). Furthermore, patients with significant psychological distress were more likely to lose weight than those without (β = 2.490, P < 0.001), and religious patients were less likely to lose weight 6 mo after gastrectomy than those without religious beliefs (β = -6.844, P = 0.001). Compared to female patients, male patients were more likely to experience weight loss 6 mo after gastrectomy (β = 4.262, P = 0.038).

Male patients with GC with high preoperative BMI, significant psychological distress, and no religious beliefs are more likely to lose weight after gastrectomy.

Core Tip: Body weight loss after surgical treatment is common in patients with gastric cancer (GC) and is associated with a poor prognosis and GC recurrence. We observed the changes of body weight in 121 patients with GC within 6 mo after surgery and analyzed the influencing factors. Our study found that preoperative body mass index, significant psychological distress, religious beliefs, and sex were risk factors for weight loss in patients with GC within 6 mo after gastrectomy.

- Citation: Li Y, Huang LH, Zhu HD, He P, Li BB, Wen LJ. Postoperative body weight change and its influencing factors in patients with gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(7): 2242-2254

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i7/2242.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2242

A recent global cancer statistics report showed that nearly 50% of new cases of gastric cancer (GC) are most likely to occur in China[1], and it is estimated that the number of patients with GC in China will reach 860000, with 679000 fatalities, by 2030[2]. The high incidence and mortality of GC pose a significant threat to human life and health, and it has become an important public health problem in China[3]. Surgical excision remains the primary curative radical treatment for patients with GC[4].

Body weight loss is a common complication after surgical treatment in patients with GC and is considered one of the few objective indicators for measuring the health status of patients after gastrectomy[5]. Body weight loss seriously impairs physical function, reduces treatment tolerance, affects quality of life, and is associated with poor prognosis and GC recurrence[6]. In particular, the percentage body weight change reflects disease severity and is an independent predictor of survival[7].

Insufficient attention has been paid to body weight change after GC surgery, and the descriptions of body weight change after GC surgery and its influencing factors differ across published studies. For example, an ongoing debate remains about the time point at which body weight loss is most pronounced[8-11], and the factors that influence the trend are inconsistent and unclear[9,12,13]. In addition, previous studies focused on demographic, clinicopathological, and therapeutic factors associated with body weight loss but did not consider other potential variables related to body weight loss, including increasingly prominent sociopsychological factors such as psychological distress.

Hence, this study explored the overall trend in body weight changes of GC patients after gastrectomy and identified factors that influence body weight changes over time. Our findings reveal patterns in body weight changes and identify risk factors that can be addressed early by the medical staff. We also found that early nutritional assessments and interventions performed to guide clinical and postoperative weight management offer insights into ongoing nutrition programs.

This prospective longitudinal study was conducted at an academic medical center located in Zhejiang Province, China. The inclusion criteria for the study participants were as follows: (1) Met the standardized diagnosis and treatment standards for GC (2018 edition)[14]; (2) Age ≥ 18 years old; (3) Undergoing radical surgery for GC; (4) Could communicate with other people and understand the content of the questionnaire; (5) Expected survival duration > 6 mo; and (6) Understood the purpose of this study and agreed and volunteered to join. The exclusion criteria for the study were as follows: Patients who had an additional malignancy, cognitive dysfunction, or a history of anxiety, depression, or other mental illnesses.

The data were collected between October 2021 and September 2022, and the initial data collection period occurred before gastrectomy. The researchers used unified guidance to facilitate questionnaire completion, collected the contact information of the patient and the main caregiver, and added patients to WeChat to inform them that they needed to complete the questionnaire, up to four times. For follow-up, the patients received a follow-up QR code and were guided to fill in the follow-up questionnaire. For the second, third, and fourth rounds of data collection, the researchers contacted the patients or their primary caregivers on WeChat, established follow-up files, and periodically sent WeChat QR codes for follow-up electronic questionnaire, as needed.

The study complied with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. All information and data from the study will be maintained as confidential and anonymous.

General information questionnaire: As designed by the investigator, the study comprised demographic data and information related to disease characteristics. The patient demographic characteristics included age, sex, occupation, residence, education level, religious beliefs, marital status, residential conditions, family monthly income, medical expense payments, and chronic underlying diseases. The disease features mainly included preoperative body mass index (BMI) classification (referring to specific Asian standards[15]), and the BMI classification was as follows: Underweight: BMI < 18.50 kg/m2; normal body weight: BMI 18.50-22.99 kg/m2; overweight: BMI 23.00-24.99 kg/m2; and obesity: BMI ≥ 25.00 kg/m2. Tumor staging followed TNM guidelines (AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edition[16]), and the surgical method, gastrectomy type, postoperative complications, perioperative chemotherapy, and preoperative chemotherapy were recorded.

Psychological distress: Psychological distress is a multifactorial, unpleasant emotional experience of psychological (cognitive, behavioral, and emotional), social, and spiritual nature. It refers to a state of emotional distress that is characterized by symptoms of depression and anxiety and has become the 6th internationally recognized vital sign[17]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends a distress thermometer (DT) be used to measure psychological distress levels in patients. The DT provides a visual analog scale that ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 represents no distress and 10 indicates extreme distress, and higher scores indicate more serious psychological distress. The patients were instructed to mark the average distress level experienced in the past week with a numerical value. According to the NCCN Clinical Practice Management Guidelines for Psychological Distress of Cancer, DT should be used as an initial screening tool. A DT score ≥ 4 should be classified as “significant psychological distress”, and patients with such scores are recommended to be referred to professional psychologists and psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment[17]. The accuracy and reliability of the Chinese version of the DT scale were confirmed by Tang et al[18], with an internal consistency coefficient Cronbach’s α = 0.80 and retest validity of 0.77.

Weight loss: The percentage weight loss was determined as follows: (Body weight at follow-up - baseline weight)/baseline weight × 100%. In this study, the baseline weight was the patient’s weight before gastrectomy, which was measured 3 d before gastrectomy. During the measurements, the subjects removed their shoes and hats, wore light clothes, removed their mobile phones, keys, and other heavy objects, and used a unified standard weight-measuring instrument. After the reading stabilized, specialized investigators read and recorded the weight value with an accurate reading of 0.01 kg. The time points at which body weight data were collected were as follows: (1) T0, 3 d before gastrectomy; (2) T1, 1 mo after gastrectomy; (3) T2, 3 mo after gastrectomy; and (4) T3, 6 mo after gastrectomy. Patients were also instructed to simultaneously note fasting measurements while wearing light clothing. A weight loss of > 5% is clinically significant[19], and a weight loss of > 10% is defined as severe weight loss[12].

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Measurement data are expressed as the mean ± SD, whereas counting data are described as frequencies and percentages. The general estimation equation was used for the statistical analysis of the dynamic change trend of overall body weight and its influencing factors, from 0 to 6 mo after gastrectomy for GC. Univariate and multivariate analyses of each influencing factor were performed with individual patients as the main variable, time as the main internal variable, and body weight as the dependent variable.

A total of 129 patients were enrolled in this study; however, eight patients were lost to follow-up, among whom five were lost due to death (two died of recurrence and metastasis 2 mo after surgery, one died of severe chemotherapy toxicity and side effects 3 mo after surgery, and two died of cerebrovascular accidents 5 mo after surgery), and three due to poor compliance. The loss to follow-up rate was 6.20%, and ultimately, 121 patients with complete data were included in the analysis. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 121 patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 63.20 years ± 9.15 years, and the mean BMI was 22.72 kg/m2 ± 3.18 kg/m2. Most of the participants were men (66.10%), were married (91.70%), and lacked religious faith (91.70%). Most were farmers (46.28%) living in rural areas (45.46%), and the most common education level was primary school (47.11%). The TNM stages of the tumors were mainly stages I and III (37.20%), and the main operative method was laparoscopy (62.80%). The main type of gastrectomy performed was partial gastrectomy (60.30%), and 68.60% of patients underwent perioperative chemotherapy, while 21.50% received preoperative chemotherapy.

| Variable | n = 121 | |

| Gender | Male | 80 (66.1) |

| Female | 41 (33.9) | |

| Age | ≥ 65 years | 61 (50.4) |

| < 65 years | 60 (49.6) | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 56 (46.3) |

| Worker | 13 (10.7) | |

| Retired | 32 (26.5) | |

| Others | 20 (16.5) | |

| Residence | Country | 55 (45.5) |

| Town | 30 (24.8) | |

| City | 36 (29.7) | |

| Education level | Elementary or below | 57 (47.1) |

| Middle school | 31 (25.6) | |

| High school | 17 (14.1) | |

| College or above | 16 (13.2) | |

| Religion | No | 111 (91.7) |

| Yes | 10 (8.3) | |

| Marriage status | Married | 111 (91.7) |

| Single or divorced or widowed | 10 (8.3) | |

| Living condition | Solitude | 11 (9.1) |

| Live with relatives | 110 (90.9) | |

| Monthly household income (RMB) | < ¥1000 | 11 (9.1) |

| ¥1000-¥3000 | 31 (25.6) | |

| ¥3000-¥5000 | 33 (27.3) | |

| ¥5000-¥10000 | 34 (28.1) | |

| ≥ ¥10000 | 12 (9.9) | |

| Payment method for medical expenses | Medical insurance | 51 (42.1) |

| Rural and urban health insurance | 70 (57.9) | |

| TNM stage | 0 | 1 (0.8) |

| I | 45 (37.2) | |

| II | 30 (24.8) | |

| III | 45 (37.2) | |

| IV | 0 (0.0) | |

| Operation mode | Laparoscopy | 76 (62.8) |

| Open surgery | 45 (37.2) | |

| Gastrectomy type | Total gastrectomy | 48 (39.7) |

| Partial gastrectomy | 73 (60.3) | |

| Postoperative complications | No | 95 (78.5) |

| Yes | 26 (21.5) | |

| Perioperative chemotherapy | No | 38 (31.4) |

| Yes | 83 (68.6) | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | No | 95 (78.5) |

| Yes | 26 (21.5) | |

| Concomitant chronic diseases | None | 67 (55.4) |

| 1 | 34 (28.1) | |

| 2 or more | 20 (16.5) | |

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2) | < 18.50 | 10 (8.3) |

| 18.50-22.99 | 62 (51.2) | |

| 23.00-24.99 | 24 (19.8) | |

| ≥ 25.00 | 25 (20.7) | |

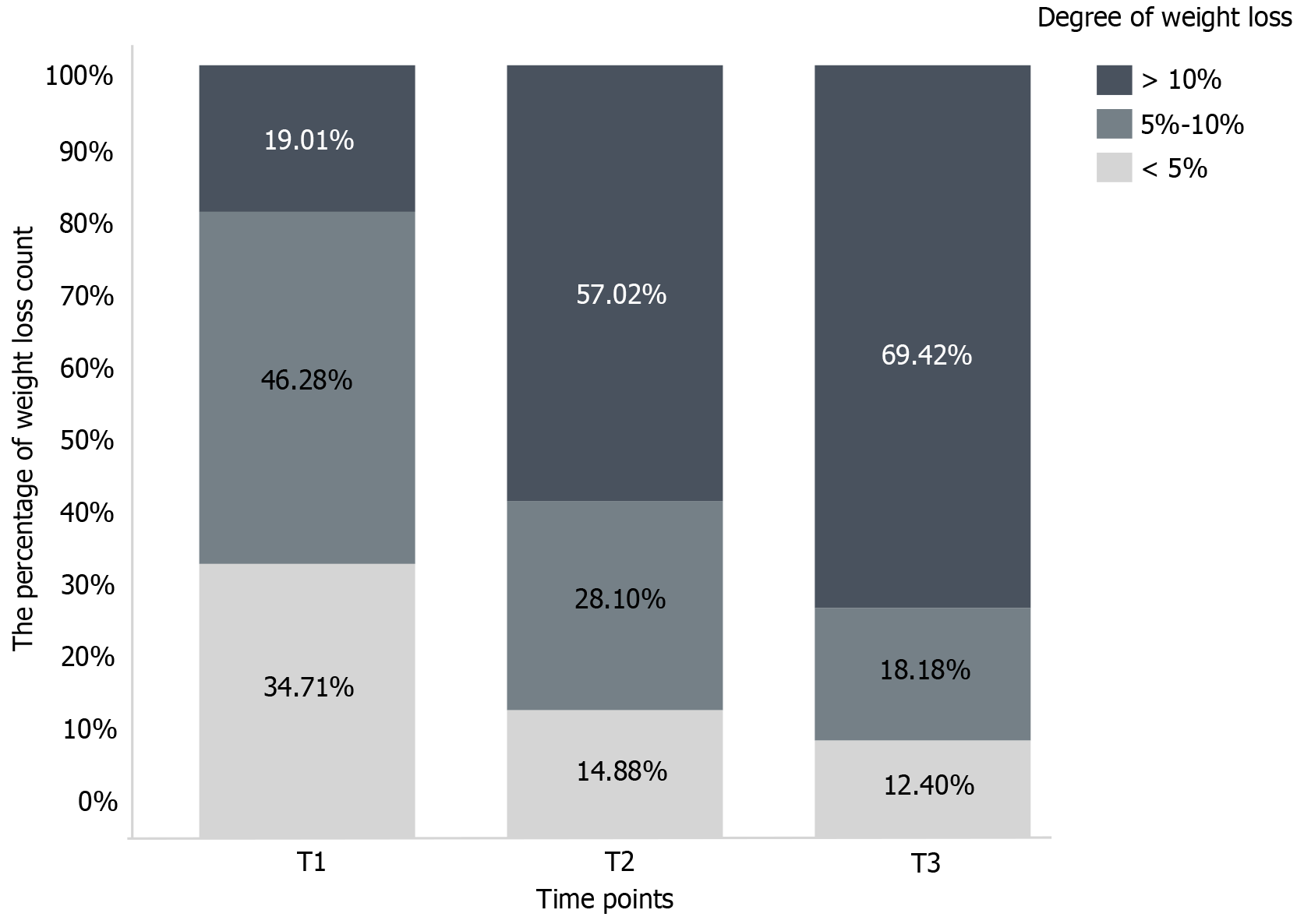

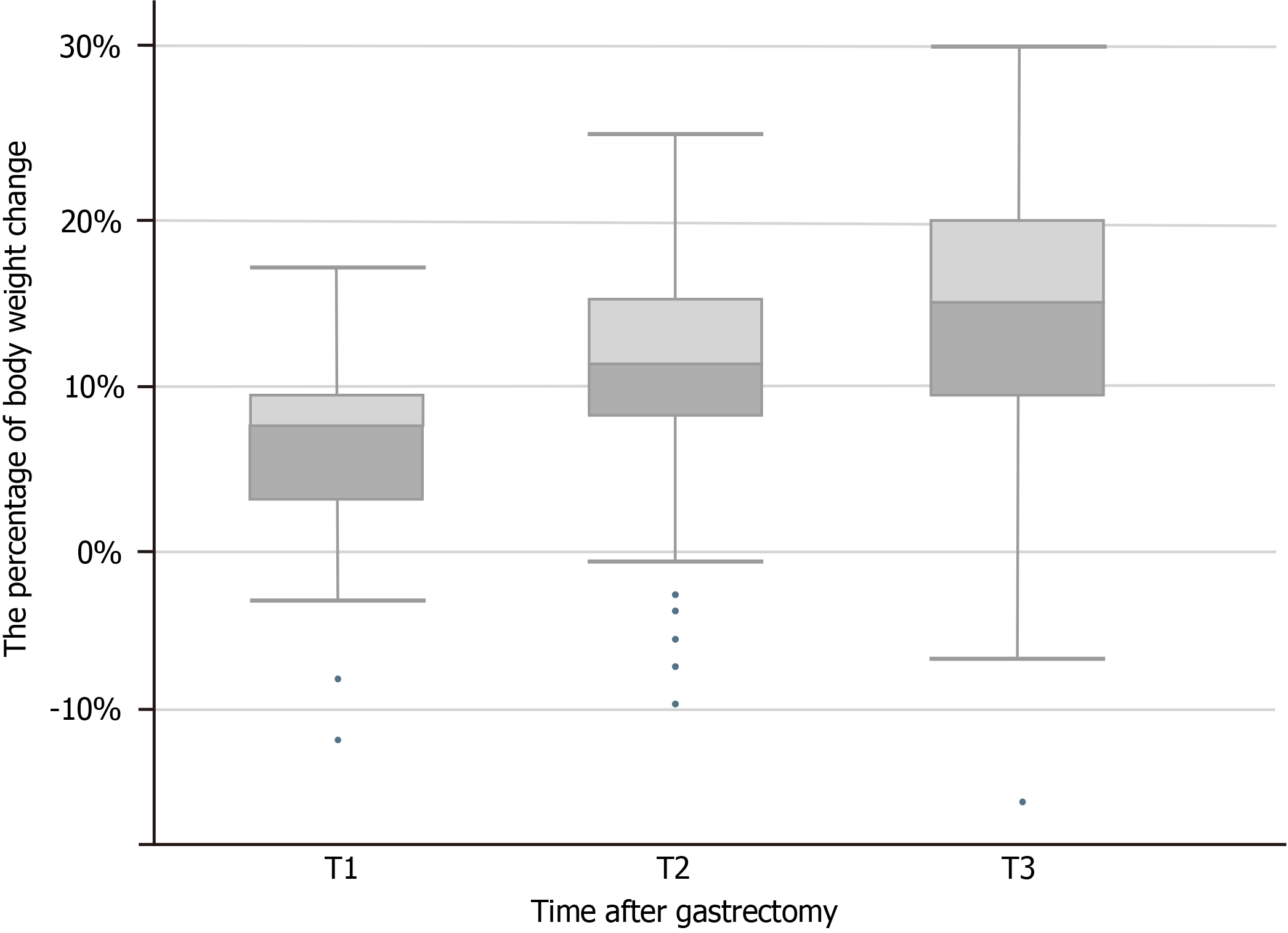

The changes in body weight in patients with GC that occurred from 0-6 mo after gastrectomy are shown in Figure 1. The degree of weight loss at T1-T3 is shown in Figure 2, and the average body weights of the patients at T0, T1, T2, and T3 were 61.23 kg ± 11.04 kg, 57.31 kg ± 10.33 kg, 54.41 kg ± 9.38 kg, and 52.39 kg ± 9.48 kg, respectively. The median weight loss at T1, T2, and T3 was 7.29% (2.84%, 9.40%), 11.11% (7.64%, 14.91%), and 14.75% (8.80%, 19.84%), respectively.

Compared with preoperative weight, the weight of patients with GC decreased from 0 to 6 mo after surgery. The results of the generalized estimation equation showed a significant effect of time (χ2 = 331.407, P < 0.001), which indicated that the weight of the patients with GC decreased within 6 mo after gastrectomy. According to the parameters of the generalized estimation equation, relative to T0, the cumulative weight losses of patients with GC were 3.89% at T1 (χ2 = 196.749, P < 0.001), 6.82% at T2 (χ2 = 291.886, P < 0.001), and 8.83% (χ2 = 283.228, P < 0.001) at T3 (Table 2).

| Variable | β | SE | 95%CI | Wald χ2 | P value | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Time point | 331.407 | < 0.001 | ||||

| T3 | -8.834 | 0.525 | -9.862 | -7.805 | 283.228 | < 0.001 |

| T2 | -6.818 | 0.399 | -7.600 | -6.035 | 291.886 | < 0.001 |

| T1 | -3.891 | 0.277 | -4.435 | -3.347 | 196.749 | < 0.001 |

| T0 | - | |||||

Demographic, disease, psychological, and other patient factors were incorporated into the generalized estimation equation model for the univariate analysis. The results indicated that sex, religious belief, marital status, method of medical expense payment, preoperative BMI classification, and significant psychological distress were significant factors that influenced the dynamic changes in body weight in patients with GC from 0 to 6 mo after gastrectomy (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Variable | β | SE | 95%CI | Wald χ2 | P value | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | ||||||

| ≥ 65 years | -1.781 | 1.771 | -5.252 | 1.691 | 1.011 | 0.315 |

| < 65 years | - | |||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 13.225 | 1.334 | 10.610 | 15.840 | 98.260 | < 0.001b |

| Female | - | |||||

| Occupation | 7.748 | 0.052 | ||||

| Farmer | -4.684 | 2.532 | -9.647 | 0.280 | 3.421 | 0.064 |

| Worker | 0.449 | 2.824 | -5.086 | 5.985 | 0.025 | 0.874 |

| Retired | -0.504 | 2.833 | -6.058 | 5.049 | 0.032 | 0.859 |

| Others | - | |||||

| Residence | 4.663 | 0.097 | ||||

| City | 3.932 | 2.115 | -0.213 | 8.077 | 3.457 | 0.063 |

| Town | 3.546 | 2.142 | -0.652 | 7.743 | 2.741 | 0.098 |

| Country | - | |||||

| Education level | 1.888 | 0.596 | ||||

| College or above | 3.164 | 2.818 | -2.359 | 8.687 | 1.261 | 0.262 |

| High school | 2.479 | 2.792 | -2.994 | 7.952 | 0.788 | 0.375 |

| Middle school | 1.797 | 2.118 | -2.355 | 5.949 | 0.720 | 0.396 |

| Primary school | - | |||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Yes | -8.611 | 3.148 | -14.781 | -2.441 | 7.482 | 0.006b |

| No | - | |||||

| Marriage status | ||||||

| Single or divorced or widowed | -11.109 | 2.451 | -15.912 | -6.306 | 20.549 | < 0.001b |

| Married | - | |||||

| Living condition | ||||||

| Live with relatives | -1.543 | 3.945 | -9.275 | 6.189 | 0.153 | 0.696 |

| Solitude | - | |||||

| Monthly household income (RMB) | 2.758 | 0.599 | ||||

| ≥ ¥10000 | 1.083 | 4.743 | -8.214 | 10.380 | 0.052 | 0.819 |

| ¥5000-¥10000 | -3.732 | 3.863 | -11.303 | 3.838 | 0.934 | 0.334 |

| ¥3000-¥5000 | -0.866 | 3.736 | -8.188 | 6.456 | 0.054 | 0.817 |

| ¥1000-¥3000 | -1.321 | 3.875 | -8.915 | 6.274 | 0.116 | 0.733 |

| < ¥1000 | - | |||||

| Payment method for medical expenses | ||||||

| Medical insurance | 3.934 | 1.719 | 0.565 | 7.303 | 5.237 | 0.022a |

| Rural and urban health insurance | - | |||||

| Concomitant chronic diseases | 3.391 | 0.183 | ||||

| 2 or more | 3.433 | 2.739 | -1.935 | 8.802 | 1.571 | 0.210 |

| 1 | 3.187 | 1.989 | -0.711 | 7.085 | 2.567 | 0.109 |

| None | - | |||||

| TNM stage | 3.234 | 0.198 | ||||

| III | -1.864 | 1.980 | -5.744 | 2.017 | 0.886 | 0.347 |

| II | 2.471 | 2.337 | -2.110 | 7.052 | 1.118 | 0.290 |

| I | - | |||||

| Operation mode | ||||||

| Open surgery | 2.018 | 1.856 | -1.620 | 5.656 | 1.182 | 0.277 |

| Laparoscopy | - | |||||

| Gastrectomy type | ||||||

| Partial gastrectomy | 2.141 | 1.789 | -1.366 | 5.649 | 1.432 | 0.231 |

| Total gastrectomy | - | |||||

| Postoperative complications | ||||||

| Yes | -1.535 | 2.346 | -6.132 | 3.063 | 0.428 | 0.513 |

| No | - | |||||

| Perioperative chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 0.777 | 1.890 | -2.927 | 4.481 | 0.169 | 0.681 |

| No | - | |||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 2.842 | 2.303 | -1.672 | 7.356 | 1.523 | 0.217 |

| No | - | |||||

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2) | 168.996 | < 0.001b | ||||

| ≥ 25.00 kg/m2 | 25.416 | 2.187 | 21.130 | 29.702 | 135.101 | < 0.001b |

| 23.00-24.99 kg/m2 | 19.058 | 2.038 | 15.063 | 23.054 | 87.417 | < 0.001b |

| 18.50-22.99 kg/m2 | 10.892 | 1.912 | 7.145 | 14.639 | 32.462 | < 0.001b |

| < 18.50 kg/m2 | - | |||||

| Significant psychological distress | ||||||

| Yes | -1.050 | 0.405 | -1.844 | -0.256 | 6.715 | 0.010a |

| No | - | |||||

The variables with statistical significance in the univariate analysis were entered into the generalized estimation equation model for multivariate analysis. The results showed that preoperative BMI, significant psychological distress, religious beliefs, and sex were risk factors for weight loss in patients with GC from 0 to 6 mo after gastrectomy. Compared with preoperative low-weight patients, preoperative patients with obesity were more likely to suffer weight loss (β = 14.685, P < 0.001). Furthermore, patients with significant psychological distress were more likely to lose weight than those without (β = 2.490, P < 0.001), and religious patients were less likely to lose weight 6 mo after gastrectomy than those who lacked religious beliefs (β = -6.844, P = 0.001). Compared to female patients, male patients were more likely to experience weight loss 6 mo after gastrectomy (β = 4.262, P = 0.038) (Table 4).

| Variable | β | SE | 95%CI | Wald χ2 | P value | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Intercept | 41.943 | 2.052 | 37.920 | 45.966 | 417.624 | < 0.001b |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 4.262 | 2.052 | 0.240 | 8.285 | 4.313 | 0.038a |

| Female | - | |||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Yes | -6.844 | 2.052 | -10.867 | -2.821 | 11.119 | 0.001b |

| No | - | |||||

| Marriage status | ||||||

| Single or divorced or widowed | -2.559 | 2.957 | -8.354 | 3.237 | 0.749 | 0.387 |

| Married | - | |||||

| Payment method for medical expenses | ||||||

| Medical insurance | 0.309 | 1.831 | -3.279 | 3.897 | 0.029 | 0.866 |

| Rural and urban health insurance | - | |||||

| Preoperative BMI | 1288.795 | < 0.001b | ||||

| ≥ 25.00 kg/m2 | 14.685 | 2.425 | 9.932 | 19.438 | 36.669 | < 0.001b |

| 23.00-24.99 kg/m2 | 12.098 | 2.052 | 8.075 | 16.120 | 34.743 | < 0.001b |

| 18.50-22.99 kg/m2 | 5.913 | 1.320 | 3.326 | 8.500 | 20.065 | < 0.001b |

| < 18.50 kg/m2 | - | |||||

| Significant psychological distress | ||||||

| Yes | 2.490 | 0.624 | 1.266 | 3.714 | 15.905 | < 0.001b |

| No | - | |||||

Herein, the results showed that compared with preoperative weight, the weight of patients with GC showed a decreasing trend over 6 mo after gastrectomy, which indicated that time had a significant effect (P < 0.001). This may be related to digestive tract reconstruction, digestive malabsorption, hormonal changes, or other factors.

This study also showed that the mean weight losses were 7.29%, 11.11%, and 14.75% at T1, T2, and T3, respectively, and that the greatest weight loss occurred during 0-1 mo. This result agrees with those of the previous studies[10,11,20] and is similar to that of Lim et al[9], though it is inconsistent with that of Du et al[8]. Furthermore, Nishigori et al[10] previously analyzed postoperative weight changes in 50 Japanese patients with GC and found that postoperative weight loss varied with time. Weight loss was > 10% during 6 mo after surgery and reached the maximum in this period, consistent with the results of this study. Lim et al[9] concluded that patients with GC continued to experience weight loss 3 mo after surgery that stagnated at 6 mo, which is in further agreement with our results. However, the average weight loss rates at 1, 3, and 5 mo after surgery were 6.38%, 5.06%, and 4.26%, respectively, which are lower than the reduction levels in this study, and this may be because only 24.7% of their patients received perioperative chemotherapy. In comparison, 68.6% of the participants in this study received perioperative chemotherapy, which may relate to the observed differences in population, race, and dietary culture[8]. A previous study suggested that the lowest weight loss was achieved within 3 mo of surgery, which is inconsistent with our results. This prior study aimed to elucidate the relationship between BMI and GC prognosis after radical gastrectomy; however, the investigators speculated that the reason for this was related to the change in body weight after gastrectomy limited to the first 3 mo after surgery. Furthermore, Segami et al[12] and Tian et al[13] conducted follow-up studies on postoperative weight changes in patients with GC; however, they only investigated the weight changes of patients within 3 mo after surgery. Their results presented a decreasing trend in patient weight, from baseline to 3 mo after surgery. In particular, the study results of Tian et al[13] showed that the weight loss in patients at 1, 3, and 4 mo after surgery was 9.2%, 11.0%, and 11.4%, respectively, which is similar to the weight loss at 1 and 3 mo after surgery in this study. However, due to the lack of continuous follow-up, patient weight at 6 mo after surgery was not reported. Possible reasons for the observed differences between the findings of prior studies are the different characteristics of the populations included in each study and follow-up duration.

Therefore, we suggest for medical professionals to strengthen the long-term follow-up of patients with GC regarding preoperative and postoperative weights, pay attention to postoperative nutritional status, and perform individualized and dynamic assessments.

Our results revealed that preoperative BMI substantially influenced postoperative weight loss 6 mo after surgery in patients with GC, in agreement with the findings of previous studies[5,20,21]. These studies showed that preoperative BMI significantly affected postoperative body weight changes in patients with GC, which indicates that preoperative BMI is an important predictor of postoperative body weight changes. However, there were notable differences among prior studies regarding specific classifications, BMI distributions, and postoperative body weight changes.

Our study revealed that preoperative patients with a high BMI or obesity were more likely to experience weight loss, which is consistent with the results of Tanabe et al[5] and Tian et al[13]. Tian et al[13] found that a higher preoperative BMI was a risk factor for weight loss 3 mo after surgery, while Tanabe et al[5] found that a higher preoperative BMI predicted greater weight loss 1 year after surgery. A possible reason for these findings is that the preoperative food intake of patients with a high BMI or obesity may be higher than that of non-obese patients, and certain normal-weight and overweight patients may lose more reserve nutrition and lack adequate immune nutrition. Higher BMI was found to be associated with an increased response to anticancer treatment; however, other studies[22] found that a low preoperative BMI of < 23 kg/m2 is associated with severe weight loss after gastrectomy. The reasons for these contradictory findings may be due to the different races of the patients, different follow-up times, various BMI criteria, and possible interactions with BMI loss. In Asian patients, low BMI is not always indicative of malnutrition; for instance, a low preoperative BMI has no adverse effects on short-term outcomes, including postoperative complications, although a low BMI may have a negative impact on prognosis[21]. These conflicting findings suggest that the mechanisms underlying postoperative weight loss in patients are complex, and further detailed long-term follow-up is needed to monitor dynamic BMI changes, particularly in body composition and muscle mass.

This study showed that psychological distress significantly impacted the weight loss of patients with GC from 0 to 6 mo after surgery. Cancer diagnosis and treatment are stressful events, and it has been reported that the incidence of psychological distress in patients with GC ranges from 33.60% to 76.97%[23,24]. Psychological distress is common in patients with GC at all stages; however, different levels of psychological distress are displayed based on various disease and treatment stages. In this study, the average incidence of psychological distress in the longitudinal survey was 40%, which was slightly higher than the result of Kim et al[23], and this may be related to the ethnic and cultural differences in the population. This rate was also lower than that reported by VanHoose et al[25], and this discrepancy may be attributable to the surveyed population in this study, which primarily comprised individuals with a low, primary school education level, vague understanding of their cancer, and unawareness of the harm caused by this cancer. Qualification for radical surgery may increase a patient’s sense of hope and patients may believe that the disease has been cured after surgery. The levels of psychological distress in our study population were lower than those reported in previous studies[24]. Additionally, the participants in this study were mainly patients with stable marriages, good social support, medical insurance payments, and stable economic status. Improvements in the Chinese medical insurance policy gradually reduced the pressure of seeing a doctor and treating diseases to a certain extent, and a combination of good social and family support may reduce psychological distress.

This study revealed that patients with significant psychological distress were more likely to experience weight loss. This is consistent with American longitudinal research results[26] on the dynamic relationship between weight loss and psychological symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer. The underlying mechanism may be related to gastrectomy involving gastrointestinal tract reconstruction, especially the alteration of the anatomical structure of the gastroduodenal junction and proximal small intestine. The small intestine is the central hub of metabolic regulation, energy homeostasis, and body weight control in the entire microbiome-gut-brain axis, and thus, postoperative digestive and absorption disorders can cause intestinal flora disorders and activate the microbiome-brain-gut axis[27]. Furthermore, microbial flora can act on the host through the gut-brain axis and thus affect brain function and behavior[28]. As a two-way communication system, the brain-gut axis comprises the autonomic nervous system, enteric nervous system, and neuroendocrine and immune pathways. Psychological factors, including psychological distress, may lead to the occurrence and development of digestive tract diseases, including unconscious weight loss, through regulatory mechanisms, such as the brain-gut and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axes[29]. British scholars[30] have previously summarized the impact of weight loss on patients with cancer and pointed out that weight loss in such patients usually leads to a series of adverse emotional experiences, such as anxiety, depression, pain, and worry. A bad mood can also decrease body defense functions through the neuroendocrine-immune pathway[31], which may be related to weight loss. Research on the correlation between weight loss and psychological factors in patients is still in a preliminary exploration stage. Further in-depth mechanistic studies must be conducted to advance knowledge in this field.

It has been suggested for medical professionals to pay attention to patient physical symptoms and psychological state during the follow-up of patients with GC after surgery, and additional attention should be paid to any changes in their psychological state and body weight.

Herein, religious beliefs were found to affect patient weight loss within 6 mo postoperatively. In modern society, religion provides an important spiritual and social force. People may reflect their spiritual needs over a specific period throughout their social life, and religion can penetrate people’s spiritual world, behavior patterns, and other aspects of their daily life[32]. Prior studies have confirmed that religion provides a common coping style and spiritual pillar for patients with cancer and affects their physical and mental health[33]. In this study, 8.3% of patients had religious beliefs, mainly Christianity and Buddhism. A possible explanation for the strong disease beliefs of patients with religious beliefs is that their beliefs stimulated their cancer prevention pursuit. This observation suggests that medical staff should provide personalized care according to the different needs of patients, such as adjusting health education content to the lives of patients based on their religious beliefs and make patients aware of the identified benefits of religious beliefs for treatment outcomes.

This study has some limitations. First, body weight loss before diagnosis was ignored, which may have biased the results. Second, the follow-up time was short, and this was a single-center study with a small sample size. In the future, the sample size should be further expanded, follow-up time extended, and population heterogeneity and potential categories comprehensively considered to further explore the long-term development and changes in the trajectory of postoperative weight loss in patients. In addition, the interactions and mechanisms of postoperative weight loss should be investigated by combining the influence and changing trends of potential psychological variables. Altogether, the findings of this study and others provide a reference for the scientific implementation of postoperative weight management in patients with GC.

The present study showed that the body weight of patients changed dynamically within 6 mo after gastrectomy. The overall body weight change presented a downward trend over time, with the fastest decrease observed from 0 to 1 mo after gastrectomy, reaching a maximum at 6 mo after gastrectomy. The dynamic changes in body weight that occurred from 0 to 6 mo after gastrectomy were affected by various factors that included preoperative BMI, significant psychological distress, religious beliefs, and sex. Thus, medical staff should pay attention to the long-term follow-up of the postoperative weight of patients with GC, monitor changes in BMI, pay attention to dynamic weight loss and psychological changes in patients, develop individualized weight management plans, and implement a comprehensive and dynamic postoperative nutrition management program to improve patient outcomes around the world.

The authors would like thank the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine and all the participants of our study for supporting the research.

| 1. | Yang WJ, Zhao HP, Yu Y, Wang JH, Guo L, Liu JY, Pu J, Lv J. Updates on global epidemiology, risk and prognostic factors of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2452-2468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 96.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 2. | Zhou J, Zheng R, Zhang S, Chen R, Wang S, Sun K, Li M, Lei S, Zhuang G, Wei W. Gastric and esophageal cancer in China 2000 to 2030: Recent trends and short-term predictions of the future burden. Cancer Med. 2022;11:1902-1912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xu H, Li W. Early detection of gastric cancer in China: progress and opportunities. Cancer Biol Med. 2022;19:1622-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Wang Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, Lu S, Chen H. Progress of Gastric Cancer Surgery in the era of Precision Medicine. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17:1041-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tanabe K, Takahashi M, Urushihara T, Nakamura Y, Yamada M, Lee SW, Tanaka S, Miki A, Ikeda M, Nakada K. Predictive factors for body weight loss and its impact on quality of life following gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4823-4830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yoon SL, Kim JA, Kelly DL, Lyon D, George TJ Jr. Predicting unintentional weight loss in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10:526-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Martin L, Senesse P, Gioulbasanis I, Antoun S, Bozzetti F, Deans C, Strasser F, Thoresen L, Jagoe RT, Chasen M, Lundholm K, Bosaeus I, Fearon KH, Baracos VE. Diagnostic criteria for the classification of cancer-associated weight loss. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:90-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Du ZD, Zhang X, Wang DP, Yu YY, Zhang WH, Li Q. Relationship between body mass index and prognosis after radical gastrectomy. Yixue Yanjiusheng Xuebao. 2019;32:258-262. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Lim HS, Lee B, Cho I, Cho GS. Nutritional and Clinical Factors Affecting Weight and Fat-Free Mass Loss after Gastrectomy in Patients with Gastric Cancer. Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nishigori T, Okabe H, Tsunoda S, Shinohara H, Obama K, Hosogi H, Hisamori S, Miyazaki K, Nakayama T, Sakai Y. Superiority of laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with hand-sewn esophagogastrostomy over total gastrectomy in improving postoperative body weight loss and quality of life. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3664-3672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Davis JL, Selby LV, Chou JF, Schattner M, Ilson DH, Capanu M, Brennan MF, Coit DG, Strong VE. Patterns and Predictors of Weight Loss After Gastrectomy for Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1639-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Segami K, Aoyama T, Kano K, Maezawa Y, Nakajima T, Ikeda K, Sato T, Fujikawa H, Hayashi T, Yamada T, Oshima T, Yukawa N, Rino Y, Masuda M, Ogata T, Cho H, Yoshikawa T. Risk factors for severe weight loss at 1 month after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Asian J Surg. 2018;41:349-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tian Q, Qin L, Zhu W, Xiong S, Wu B. Analysis of factors contributing to postoperative body weight change in patients with gastric cancer: based on generalized estimation equation. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | In H, Ravetch E, Langdon-Embry M, Palis B, Ajani JA, Hofstetter WL, Kelsen DP, Sano T. The newly proposed clinical and post-neoadjuvant treatment staging classifications for gastric adenocarcinoma for the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park SK, Ryoo JH, Oh CM, Choi JM, Kang JG, Lee JH, Chung JY, Jung JY. Effect of Overweight and Obesity (Defined by Asian-Specific Cutoff Criteria) on Left Ventricular Diastolic Function and Structure in a General Korean Population. Circ J. 2016;80:2489-2495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2341] [Cited by in RCA: 4405] [Article Influence: 550.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 17. | Riba MB, Donovan KA, Andersen B, Braun I, Breitbart WS, Brewer BW, Buchmann LO, Clark MM, Collins M, Corbett C, Fleishman S, Garcia S, Greenberg DB, Handzo RGF, Hoofring L, Huang CH, Lally R, Martin S, McGuffey L, Mitchell W, Morrison LJ, Pailler M, Palesh O, Parnes F, Pazar JP, Ralston L, Salman J, Shannon-Dudley MM, Valentine AD, McMillian NR, Darlow SD. Distress Management, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1229-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 441] [Article Influence: 73.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tang LL, Zhang YN, Pang Y, Zhang HW, Song LL. Validation and reliability of distress thermometer in chinese cancer patients. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Son YG, Kwon IG, Ryu SW. Assessment of nutritional status in laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee SE, Lee JH, Ryu KW, Nam B, Kim CG, Park SR, Kook MC, Kim YW. Changing pattern of postoperative body weight and its association with recurrence and survival after curative resection for gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:430-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Komatsu S, Kosuga T, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Preoperative Low Weight Affects Long-term Outcomes Following Curative Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:5331-5337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park YS, Park DJ, Lee Y, Park KB, Min SH, Ahn SH, Kim HH. Prognostic Roles of Perioperative Body Mass Index and Weight Loss in the Long-Term Survival of Gastric Cancer Patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:955-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim GM, Kim SJ, Song SK, Kim HR, Kang BD, Noh SH, Chung HC, Kim KR, Rha SY. Prevalence and prognostic implications of psychological distress in patients with gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hong J, Wei Z, Wang W. Preoperative psychological distress, coping and quality of life in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed gastric cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2439-2447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | VanHoose L, Black LL, Doty K, Sabata D, Twumasi-Ankrah P, Taylor S, Johnson R. An analysis of the distress thermometer problem list and distress in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1225-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Van Liew JR, Brock RL, Christensen AJ, Karnell LH, Pagedar NA, Funk GF. Weight loss after head and neck cancer: A dynamic relationship with depressive symptoms. Head Neck. 2017;39:370-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Joseph PV, Nolden A, Kober KM, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Conley YP, Hammer MJ, Wright F, Levine JD, Miaskowski C. Fatigue, Stress, and Functional Status are Associated With Taste Changes in Oncology Patients Receiving Chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62:373-382.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Artemieva MS, Kuznetsov VI, Sturov NV, Manyakin IS, Basova EA, Shumeyko D. Psychosomatic Aspects and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Pathology. Psychiatr Danub. 2021;33:1327-1329. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Cryan JF, O′Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, Sandhu KV, Bastiaanssen TFS, Boehme M, Codagnone MG, Cussotto S, Fulling C, Golubeva AV, Guzzetta KE, Jaggar M, Long-Smith CM, Lyte JM, Martin JA, Molinero-Perez A, Moloney G, Morelli E, Morillas E, O’Connor R, Cruz-Pereira JS, Peterson VL, Rea K, Ritz NL, Sherwin E, Spichak S, Teichman EM, van de Wouw M, Ventura-Silva AP, Wallace-Fitzsimons SE, Hyland N, Clarke G, Dinan TG. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:1877-2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1156] [Cited by in RCA: 2792] [Article Influence: 465.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 30. | Escamilla DM, Jarrett P. The impact of weight loss on patients with cancer. Nurs Times. 2016;112:20-22. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Qin HY, Cheng CW, Tang XD, Bian ZX. Impact of psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14126-14131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 32. | McCullough ME, Willoughby BL. Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:69-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Toledo G, Ochoa CY, Farias AJ. Religion and spirituality: their role in the psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer and subsequent symptom management of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:3017-3024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |