Published online Jul 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2088

Revised: May 18, 2024

Accepted: June 18, 2024

Published online: July 27, 2024

Processing time: 141 Days and 21.7 Hours

Bariatric surgery is one of the most effective ways to treat morbid obesity, and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is one of the common complications after bariatric surgery. At present, the mechanism of the high incidence of PONV after weight-loss surgery has not been clearly explained, and this study aims to investigate the effect of surgical position on PONV in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

To explore the effect of the operative position during bariatric surgery on PONV.

Data from obese patients, who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in the authors’ hospital between June 2020 and February 2022 were divided into 2 groups and retrospectively analyzed. Multivariable logistic regression analysis and the t-test were used to study the influence of operative position on PONV.

There were 15 cases of PONV in the supine split-leg group (incidence rate, 50%) and 11 in the supine group (incidence rate, 36.7%) (P = 0.297). The mean operative duration in the supine split-leg group was 168.23 ± 46.24 minutes and 140.60 ± 32.256 minutes in the supine group (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis revealed that operative position was not an independent risk factor for PONV (odds ratio = 1.192, 95% confidence interval: 0.376-3.778, P = 0.766).

Operative position during LSG may affect PONV; however, the difference in the incidence of PONV was not statistically significant. Operative position should be carefully considered for obese patients before surgery.

Core Tip: Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is associated with a high incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). The incidence of PONV was higher in those who underwent the procedure in the supine split-leg position vs those who were supine; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Operative position may affect operative duration, although it is not a risk factor for PONV.

- Citation: Li ZP, Song YC, Li YL, Guo D, Chen D, Li Y. Association between operative position and postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(7): 2088-2095

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i7/2088.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2088

The global prevalence of obesity and obesity-related illnesses is escalating. Up to 2.1 billion individuals worldwide are categorized as overweight or obese[1]. Numerous studies have established a definitive link between obesity and several diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and coronavirus disease 2019[2-5]. Bariatric surgery has proven to be one of the most effective interventions for metabolic regulation and weight reduction among obese patients[6]. Among the most frequently performed procedures is laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). Bariatric surgery has been shown to be one of the most effective intervention for metabolic control and weight loss in patients with obesity[7,8].

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a prevalent complication after surgery, particularly in bariatric procedures. According to studies, the incidence of PONV can reach up to 59.6% in bariatric surgery patients[9]. PONV can lead to several potential secondary complications, such as aspiration, incision rupture, higher medical costs, and an increased risk of postoperative bleeding[10]. Notably, dehydration caused by vomiting is a common reason for readmission following bariatric surgery[11]. Risk factors for PONV include being female, young age, the use of volatile anesthetics, preoperative reflux symptoms, non-smoking status, the administration of postoperative opioids, and prolonged anesthesia duration[12]. However, specific risk factors in bariatric surgery patients have not been identified. Operative positions refer to the positions of the patient during the operation. Proper operative positions are convenient to the exposure of the surgical field and the operative procedure. There are few studies on operative positions in terms of bariatric surgery. This study aimed to investigate the influence of operative positions for PONV in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (Qingdao, China; Ethics Approval Number: QYFY WZLL27397). The inclusion criteria were as follows: LSG; no postoperative complica

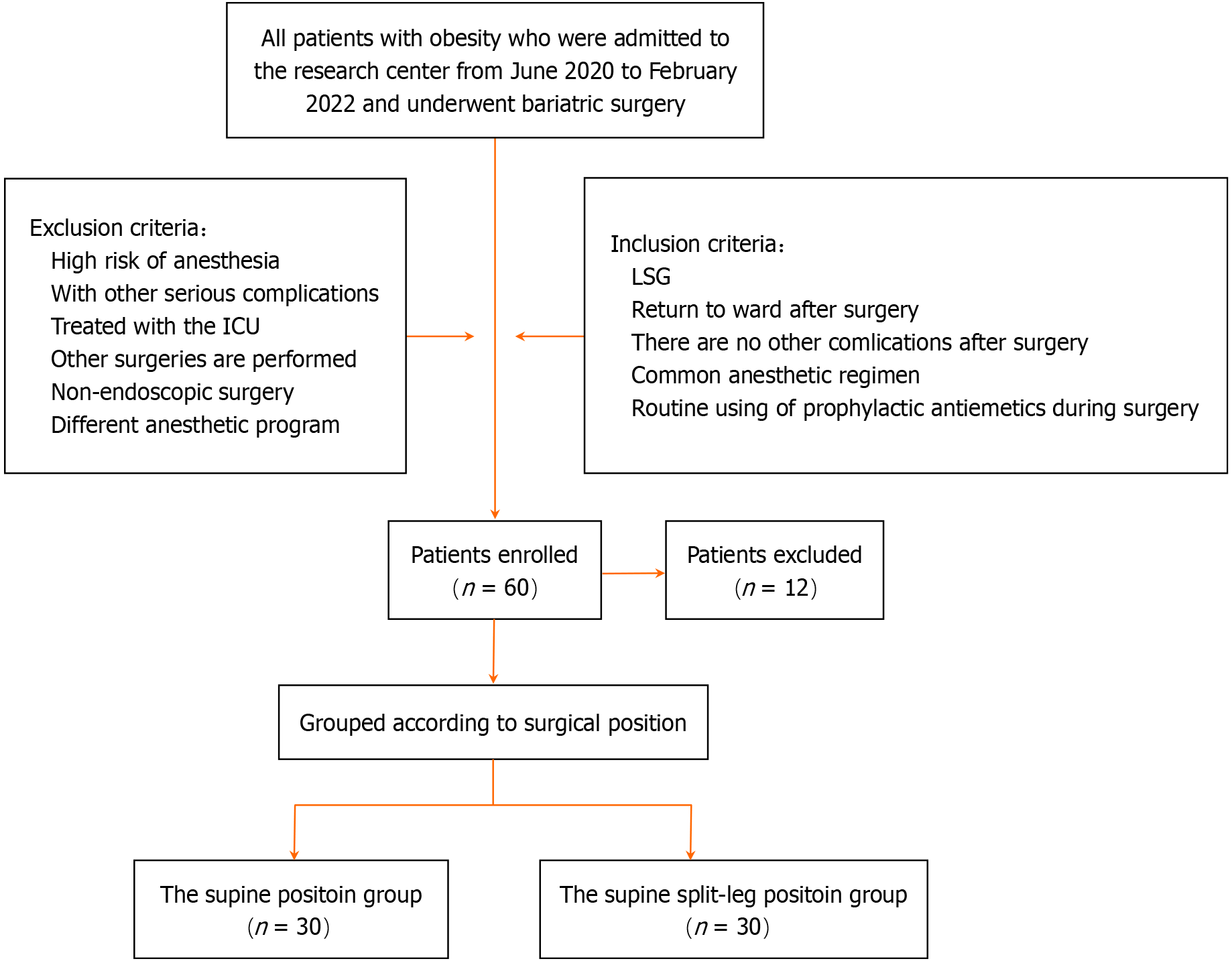

Seventy-two patients were initially eligible for this study; however, after screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 60 were ultimately included. Patients were divided into two groups according to surgical position and period: Supine split-leg, between June 2020 and July 2021 (n = 30); and supine, between August 2021 and February 2022 (n = 30). Reasons for exclusion were as follows: Serious complications of obesity (n = 3); history of treatment in the intensive care unit (n = 6); undergone other surgeries (n = 2); and different anesthetic protocol (n = 1) (Figure 1).

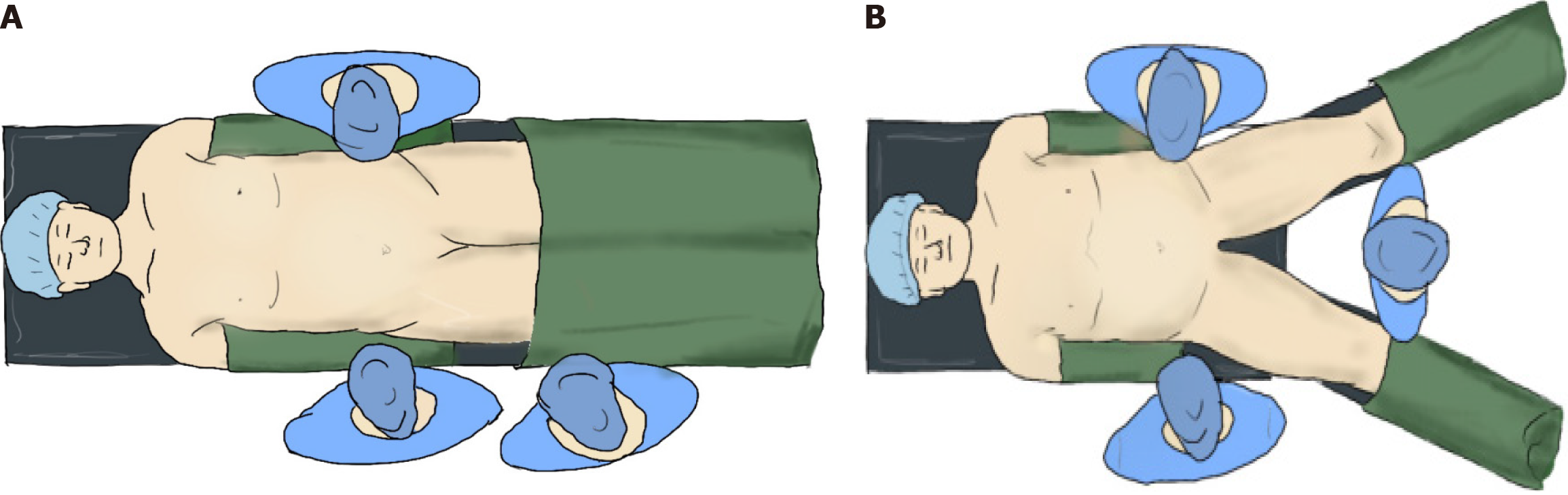

Patients who underwent surgery positioned supine were placed in the middle of the bed, with hands on both sides of the body and legs fixed to the operating bed to ensure the head was high and feet were low during the procedure (Figure 2A). Patients who underwent surgery in the supine split-leg position had their legs on the footrest after laying flat on the operating bed, separating the legs, keeping the included angle between the legs at < 90° and properly fixed (Figure 2B). During the procedure, the patients were adjusted to the reverse Trendelenburg position (the angle was maintained at 30°); operative positions were not altered and efforts were made to ensure stability of both operative positions. Possible differences between the 2 operative positions were considered to be consistent. None of the patients received postoperative nasal tubes. All patient information was obtained in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Research Committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Anesthetic management followed a standardized clinical protocol. All patients were treated by the same anesthesia team, and sufentanil, propofol, etomidate, and sevoflurane for inhalation were used to induce and maintain anesthesia. According to recent studies and guidelines, antiemetics are routinely used during the operation[14-16]. The specific scheme was intravenous ondansetron hydrochloride (8 mg)/intravenous dolasetron mesylate (12.5 mg).

Postoperatively, the patients were transferred to the general ward and their vital signs were closely monitored. Proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics were routinely used in the ward. The patients were evaluated for nausea and vomiting using a numerical rating scale (NRS). To promote early recovery, patients were encouraged to get out of bed early on the day after the operation.

Antiemetics were used in patients experiencing ≥ 2 episodes of vomiting or retching, and any nausea lasting > 30 minutes when the patient requested treatment. Based on numerical rating scale results, symptoms after surgery were treated with antiemetics, including metoclopramide (10 mg) intramuscular injection and ondansetron hydrochloride (8 mg) intravenous injection. The nursing team would monitor patient vital signs. If the patients experienced serious complications, such as arrhythmia and heart failure, the study was discontinued. Finally, the occurrence of PONV was evaluated based on the use of antiemetics and follow-up after surgery.

This retrospective study included data from patients with obesity who were admitted to and underwent bariatric surgery at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University between June 2020 and February 2022. Medical records were collected and reviewed, mainly recording the following data: Demographic and clinical data, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and time of use of antiemetics after surgery, as well as some details during the operation, including anesthesia plan, operation preparation time, operative duration, anesthesia recovery time after surgery, and use of antiemetics.

Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean ± SD, while those that were non-normally distributed are expressed as median (interquartile range). Continuous variables were analyzed using the t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and classified variables were compared using the χ2 test. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to study the factors influencing postoperative complica

Data from 60 patients with obesity who underwent LSG between June 2020 and February 2022 were reviewed. Demographic information of all patients is summarized in Table 1.

| Variable | The supine position group | The supine split-leg position group | P value |

| Age (year) | 32.27 ± 7.00 | 30.40 ± 6.04 | 0.273 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 39.88 ± 5.48 | 39.90 ± 4.83 | 0.986 |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 24 (80) | 28 (93) | 0.490 |

| Smoking | 12 | 2 | 0.002a |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 141.1 ± 16.90 | 131.77 ± 17.11 | 0.038a |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 93.77 ± 13.18 | 88.93 ± 12.20 | 0.146 |

| Blood uric acid (μmol/L) | 402.00 (376.00, 485.25) | 409.50 (343.25, 464.00) | 0.124 |

| Fasting blood-glucose (mmol/L) | 5.44 (4.80, 6.96) | 5.04 (4.59, 5.62) | 0.311 |

| ALT (U/L) | 42.50 (18.25, 82.25) | 27.00 (17.00, 44.75) | 0.149 |

| AST (U/L) | 27.00 (18.50, 47.50) | 21.00 (17.00, 30.25) | 0.120 |

Relevant data regarding the operative process in the 2 groups (i.e., supine split-leg vs supine) are summarized in Table 2. In the supine split-leg group, the mean preoperative preparation time was 35.00 ± 22.25 minutes, operative duration was 168.23 ± 46.24 minutes, anesthesia recovery time was 50.0 ± 30.00 minutes, and duration of hospitalization was 4 ± 1 days. In the supine group, the mean preoperative preparation time was 35.00 ± 21.25 minutes, operative duration was 140.60 ± 32.256 minutes, anesthesia recovery time was 42.5 ± 16.00 minutes, and length of hospitalization was 4 days. There were significant differences in operative duration between the 2 groups (P < 0.05).

| Variable | The supine position group | The supine split-leg position group | P value |

| Preparation time before surgery (minute) | 35.00 (28.75, 50.00) | 35.00 (28.75, 50.00) | 0.834 |

| Operation time (minute) | 140.60 ± 32.26 | 168.23 ± 46.24 | 0.009a |

| Anesthesia recovery time (minute) | 42.5 (39.00, 55.00) | 50.00 (40.00, 70.00) | 0.05 |

| Hospitalization time (day) | 4 (1) | 4 (0) | 0.181 |

Data from 60 patients who underwent bariatric surgery were collected for this study, of whom 26 experienced PONV: 15 in the supine split-leg group and 11 in the supine group. In the supine group, 11 patients were administered antiemetics 1-2 times and 4 were treated > 3 times. Six patients required treatment within 0-6 hours, 2 were treated for 6-12 hours, and 7 were treated for > 12 hours. In the split-leg group, 9 patients were administered antiemetics 1-2 times and 2 were treated > 3 times. Five patients were treated within 0-6 hours, 2 for 6-12 hours, and 4 for > 12 hours. The differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Patient vomiting status and the use of antiemetics are summarized in Table 3.

| Variable | The supine position group | The supine split-leg position group | P value |

| Vomiting | 11 (36.7%) | 15 (50.0%) | 0.297 |

| Number of antiemetics applications (frequency) | |||

| 0 | 19 | 15 | 0.599 |

| 1-2 | 9 | 11 | |

| > 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| Time of application of vomiting medicine | |||

| - | 19 | 15 | 0.736 |

| 0-6 hours | 5 | 6 | |

| 6-12 hours | 2 | 2 | |

| > 12 hours | 4 | 7 |

Previous studies have reported that smoking, BMI, sex, and other conditions are associated with the occurrence of PONV[17]. Subsequently, risk factors for PONV were analyzed using multivariate analysis. Regarding the factors associated with the occurrence of PONV, there were no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) between smoking status, BMI, and sex. Results revealed that operative position was not an independent risk factor for PONV (OR = 1.192, 95%CI: 0.376-3.778, P = 0.766) (Table 4).

| Influencing factor | P value | OR | 95% confidence interval | |

| Superior limit | Lower limit | |||

| Position | 0.766 | 1.192 | 0.376 | 3.778 |

| Gender | 0.585 | 0.603 | 0.098 | 3.712 |

| BMI | 0.515 | 1.038 | 0.927 | 1.163 |

| Smoking | 0.161 | 2.97 | 0.649 | 13.592 |

The current research indicates that the incidence of PONV in bariatric surgery is notably higher than in other routine surgeries, as evidenced by studies[18-21]. However, the mechanism behind this high incidence of PONV has not been fully explained. In clinical practice, the incidence of PONV varies depending on the operative positions. This study aims to elucidate the high incidence of PONV from a different perspective.

Operative positions refer to the positioning of the patient during surgery. Ensuring the correct operative positions is crucial for the well-being of patients[22]. Numerous operative positions can be employed during laparoscopic surgery and play a significant role, particularly in the realm of intraoperative anesthesia[23]. Many postoperative complications, including spinal cord injury, are associated with operative positions[24]. Despite being a common postoperative complication, there are limited studies exploring the effects of operative positions on PONV. This research focuses on the correlation between PONV and operative positions, and it has gathered a portion of surgical data for analysis.

Operative positions refer to the patient’s position during surgery. The correct operative position is crucial for patients. Various operative positions can be used for laparoscopic surgery and play a significant role in the surgical procedure, especially in the realm of intraoperative anesthesia. Many postoperative complications are tied to operative positions, including spinal cord injury. Several studies have shown that the incidence of PONV after bariatric surgery is high[19,21]. Researchers found that the occurrence of PONV reaches up to 90% in LSG[18], which differs from our findings.

In our results, over 43.3% of patients developed PONV. Among them, 36.7% of patients experienced PONV in the supine position group, while 50.0% of patients did so in the supine split-leg position group. Regarding the administration of antiemetics, some researchers found that nearly all patients diagnosed with PONV received their first rescue medication within 6 hours after surgery. However, in another study, about 46.0% of patients received their first rescue antiemetic within 6 hours post-surgery[9]. In our study, only 18.3% of patients had their first rescue medication within 6 hours, with 16% in the supine position group and 20% in the supine split-leg position group.

A possible explanation for this difference is that prophylactic antiemetics were administered at the end of surgery. Routine intraoperative use of prophylactic antiemetics may reduce the likelihood of PONV in patients within 6 hours after surgery[14,15,25]. For patients who still experience PONV, we attribute it to their larger weight base, and the number of anesthetics used during surgery is also higher than in ordinary individuals. A study pointed out that PONV and the administration of antiemetics lead to a prolonged hospital stay for patients[26]. However, our results confirmed that there was no significant difference in hospital stay between the two groups, which may be related to the small number of cases we studied.

In our research, we observed no significant difference in preoperative preparation time between the two groups, likely attributed to our mature team collaboration. However, there was a notable difference in operation time, where the operation time in our study was significantly longer than reported in relevant literature[27]. The potential explanations for this are as follows: Firstly, during surgical procedures, we routinely suture and reinforce the cutting margin, which subsequently prolongs the operation time. Secondly, it is worth noting that the operation time in our study refers to the duration from the commencement of anesthesia to its conclusion, rather than solely the time required for surgical manipulation. Thirdly, this discrepancy may be related to the learning curve of our surgical team. Furthermore, the operation time in the supine split-leg position group was significantly longer compared to the supine position group. This is likely due to the enhanced convenience for surgeons and assistants during the operation in the supine position, as well as the improved accessibility for the instrument nurse to observe the operating table.

In multivariable logistic regression analyses, smoking, BMI, and gender have been confirmed as not being risk factors for PONV, consistent with previous studies[9], yet differing from the findings of Apfel et al[28]. We posit this may be due to the lack of statistical difference in gender and BMI among patients undergoing various surgical procedures before surgery, as well as the small sample size in this single-center retrospective study. Research has revealed a possible association between opioid usage and PONV issues[23]. The recovery time from anesthesia is primarily linked to the patient's intraoperative medication dosage and individual body metabolism[12,13]. Operation time can be influenced by surgical positions; longer operations tend to require higher anesthesia doses. In our results, the supine split-leg position group had an average operation time of 168.23 ± 46.24 minutes, whereas the supine position group’s operation time was 140.60 ± 32.256 minutes. The supine split-leg position group required significantly more time compared to the supine position group. Consequently, anesthesia doses were higher in the supine split-leg position group due to the varying operation times. We anticipated differences in PONV incidence, yet surprisingly, the probability of PONV was not significantly different between the two groups. Surgical position was also not a risk factor for PONV, contrary to the results of Hozumi et al[27]. Our study found that 26 patients undergoing LSG experienced PONV, with an incidence of 50% in the supine split-leg position group and 36.7% in the supine position group (P = 0.297). This discrepancy may stem from several reasons. Primarily, PONV is a subjective research indicator, and tolerance varies among individuals. Secondary, this study only performed the analysis for the incidence of PONV and the extent of PONV was not considered. Thirdly, the quality of assessment for PONV in our study might be poor compared with well-planned prospective study.

In summary, our study revealed the impact of operative positions on the occurrence of PONV. We speculate that this could be attributed to the influence of operative positions on the intraoperative anesthesia dosage. Therefore, careful selection of operative positions during preoperative management is crucial. Our research does have certain limitations. Firstly, we were unable to collect intraoperative data regarding the amount of anesthesia administered. Secondly, our utilization of antiemetics relies heavily on patients’ subjective factors. Due to individual differences in tolerance, it is challenging to ensure consistency in symptom relief when administering antiemetics to each patient. Lastly, owing to the learning curve, there are disparities in surgeons’ proficiency. As a result, further prospective studies are necessary to validate the effect of operative positions on PONV.

LSG procedures exhibited a high rate of PONV. Specifically, the incidence of PONV was greater in the supine split-leg position group (50%) compared to the supine position group (36.7%), though this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.297). Our findings indicate that operative positions can indeed influence the duration of surgery, although they do not constitute a risk factor for PONV. Therefore, we recommend careful selection of operative positions for these patients.

| 1. | Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, Abraham JP, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Achoki T, AlBuhairan FS, Alemu ZA, Alfonso R, Ali MK, Ali R, Guzman NA, Ammar W, Anwari P, Banerjee A, Barquera S, Basu S, Bennett DA, Bhutta Z, Blore J, Cabral N, Nonato IC, Chang JC, Chowdhury R, Courville KJ, Criqui MH, Cundiff DK, Dabhadkar KC, Dandona L, Davis A, Dayama A, Dharmaratne SD, Ding EL, Durrani AM, Esteghamati A, Farzadfar F, Fay DF, Feigin VL, Flaxman A, Forouzanfar MH, Goto A, Green MA, Gupta R, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hankey GJ, Harewood HC, Havmoeller R, Hay S, Hernandez L, Husseini A, Idrisov BT, Ikeda N, Islami F, Jahangir E, Jassal SK, Jee SH, Jeffreys M, Jonas JB, Kabagambe EK, Khalifa SE, Kengne AP, Khader YS, Khang YH, Kim D, Kimokoti RW, Kinge JM, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Kwan G, Lai T, Leinsalu M, Li Y, Liang X, Liu S, Logroscino G, Lotufo PA, Lu Y, Ma J, Mainoo NK, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Mokdad AH, Moschandreas J, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Nand D, Narayan KM, Nelson EL, Neuhouser ML, Nisar MI, Ohkubo T, Oti SO, Pedroza A, Prabhakaran D, Roy N, Sampson U, Seo H, Sepanlou SG, Shibuya K, Shiri R, Shiue I, Singh GM, Singh JA, Skirbekk V, Stapelberg NJ, Sturua L, Sykes BL, Tobias M, Tran BX, Trasande L, Toyoshima H, van de Vijver S, Vasankari TJ, Veerman JL, Velasquez-Melendez G, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wang C, Wang X, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wright JL, Yang YC, Yatsuya H, Yoon J, Yoon SJ, Zhao Y, Zhou M, Zhu S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Gakidou E. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7951] [Cited by in RCA: 8006] [Article Influence: 727.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:968-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, Raverdy V, Noulette J, Duhamel A, Labreuche J, Mathieu D, Pattou F, Jourdain M; LICORN and the Lille COVID-19 and Obesity study group. High Prevalence of Obesity in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) Requiring Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28:1195-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1263] [Cited by in RCA: 1577] [Article Influence: 315.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Song Y, Zhang J, Wang H, Guo D, Yuan C, Liu B, Zhong H, Li D, Li Y. A novel immune-related genes signature after bariatric surgery is histologically associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Adipocyte. 2021;10:424-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Pergola G, Silvestris F. Obesity as a major risk factor for cancer. J Obes. 2013;2013:291546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 581] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Suh S, Helm M, Kindel TL, Goldblatt MI, Gould JC, Higgins RM. The impact of nausea on post-operative outcomes in bariatric surgery patients. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:3085-3091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Ramos A, Shikora S, Kow L. Bariatric Surgery Survey 2018: Similarities and Disparities Among the 5 IFSO Chapters. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1937-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 81.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Welbourn R, Hollyman M, Kinsman R, Dixon J, Liem R, Ottosson J, Ramos A, Våge V, Al-Sabah S, Brown W, Cohen R, Walton P, Himpens J. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide: Baseline Demographic Description and One-Year Outcomes from the Fourth IFSO Global Registry Report 2018. Obes Surg. 2019;29:782-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 80.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhu J, Wu L, Chen G, Zhao X, Chen W, Dong Z, Chen X, Hu S, Xie X, Wang C, Wang H, Yang W; Chinese Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Collaborative. Preoperative reflux or regurgitation symptoms are independent predictors of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients undergoing bariatric surgery: a propensity score matching analysis. Obes Surg. 2022;32:819-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hooper VD. PONV/PDNV: Why Is It Still the "Big Little Problem?". J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:375-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Celio A, Bayouth L, Burruss MB, Spaniolas K. Prospective Assessment of Postoperative Nausea Early After Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2019;29:858-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, Chung F, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, Jin Z, Kovac AL, Meyer TA, Urman RD, Apfel CC, Ayad S, Beagley L, Candiotti K, Englesakis M, Hedrick TL, Kranke P, Lee S, Lipman D, Minkowitz HS, Morton J, Philip BK. Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:411-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 123.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gan TJ, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, Kovac A, Kranke P, Meyer TA, Watcha M, Chung F, Angus S, Apfel CC, Bergese SD, Candiotti KA, Chan MT, Davis PJ, Hooper VD, Lagoo-Deenadayalan S, Myles P, Nezat G, Philip BK, Tramèr MR; Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:85-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 941] [Cited by in RCA: 941] [Article Influence: 85.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Naeem Z, Chen IL, Pryor AD, Docimo S, Gan TJ, Spaniolas K. Antiemetic Prophylaxis and Anesthetic Approaches to Reduce Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Bariatric Surgery Patients: a Systematic Review. Obes Surg. 2020;30:3188-3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moussa AA, Oregan PJ. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery--granisetron alone vs granisetron combined with dexamethasone/droperidol. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2007;19:357-367. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Samieirad S, Sharifian-Attar A, Eshghpour M, Mianbandi V, Shadkam E, Hosseini-Abrishami M, Hashemipour MS. Comparison of Ondansetron versus Clonidine efficacy for prevention of postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting after orthognathic surgeries: A triple blind randomized controlled trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018;23:e767-e776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stoops S, Kovac A. New insights into the pathophysiology and risk factors for PONV. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34:667-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fathy M, Abdel-Razik MA, Elshobaky A, Emile SH, El-Rahmawy G, Farid A, Elbanna HG. Impact of Pyloric Injection of Magnesium Sulfate-Lidocaine Mixture on Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: a Randomized-Controlled Trial. Obes Surg. 2019;29:1614-1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Groene P, Eisenlohr J, Zeuzem C, Dudok S, Karcz K, Hofmann-Kiefer K. Postoperative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery in comparison to non-bariatric gastric surgery. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2019;14:90-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Halliday TA, Sundqvist J, Hultin M, Walldén J. Post-operative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery patients: an observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017;61:471-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zheng XZ, Cheng B, Luo J, Xiong QJ, Min S, Wei K. The characteristics and risk factors of the postoperative nausea and vomiting in female patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic gynecological surgeries: a propensity score matching analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:182-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Burlingame BL. Guideline Implementation: Positioning the Patient. AORN J. 2017;106:227-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Oti C, Mahendran M, Sabir N. Anaesthesia for laparoscopic surgery. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2016;77:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hewson DW, Bedforth NM, Hardman JG. Spinal cord injury arising in anaesthesia practice. Anaesthesia. 2018;73 Suppl 1:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bamgbade OA, Oluwole O, Khaw RR. Perioperative Antiemetic Therapy for Fast-Track Laparoscopic Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1296-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schumann R, Ziemann-Gimmel P, Sultana A, Eldawlatly AA, Kothari SN, Shah S, Wadhwa A. Postoperative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery: a position statement endorsed by the ASMBS and the ISPCOP. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17:1829-1833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hozumi J, Egi M, Sugita S, Sato T. Dose of intraoperative remifentanil administration is independently associated with increase in the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting in elective mastectomy under general anesthesia. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Apfel CC, Philip BK, Cakmakkaya OS, Shilling A, Shi YY, Leslie JB, Allard M, Turan A, Windle P, Odom-Forren J, Hooper VD, Radke OC, Ruiz J, Kovac A. Who is at risk for postdischarge nausea and vomiting after ambulatory surgery? Anesthesiology. 2012;117:475-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |