Published online Jul 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2080

Revised: May 10, 2024

Accepted: June 7, 2024

Published online: July 27, 2024

Processing time: 144 Days and 3.6 Hours

Currently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) plus laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the main treatment for cholecystolithiasis com

To determine the clinical efficacy of LC plus cholangioscopy for cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis.

Patients (n = 243) with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis admitted to The Affiliated Haixia Hospital of Huaqiao University (910th Hospital of Joint Logistic Support Force) between January 2019 and December 2023 were included in the study; 111 patients (control group) underwent ERCP + LC and 132 patients (observation group) underwent LC + laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE). Surgical success rates, residual stone rates, complications (pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia, biliary tract infection, and bile leakage), surgical indicators [intraoperative blood loss (IBL) and operation time (OT)], recovery indices (postoperative exhaust/defecation time and hospital stay), and serum inflammatory markers [C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were compared.

No significant differences in surgical success rates and residual stone rates were detected between the observation and control groups. However, the complication rate, IBL, OT, postoperative exhaust/defecation time, and hospital stays were significantly reduced in the observation group compared with the control group. Furthermore, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 Levels after treatment were reduced in the observation group compared with the levels in the control group.

These results indicate that LC + LCBDE is safer than ERCP + LC for the treatment of cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis. The surgical risks and postoperative complications were lower in the observation group compared with the control group. Thus, patients may recover quickly with less inflammation after LCBDE.

Core Tip: Choledocholithiasis occurs in 10%–18% of patients with cholecystolithiasis. At present, the main treatment for cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) combined with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC). However, this treatment has several disadvantages. In this study, the treatment outcomes of patients with cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis were compared after LC + laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) vs ERCP + LC + LCBDE. Clinical efficacy was better ERCP + LC, patient recovery was accelerated, and surgical risks, postoperative complications, and serum inflammatory factors were lower after LC + LCBDE compared with ERCP + LC.

- Citation: Liu CH, Chen ZW, Yu Z, Liu HY, Pan JS, Qiu SS. Clinical efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy plus cholangioscopy for the treatment of cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(7): 2080-2087

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i7/2080.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2080

Choledocholithiasis occurs in 10%–18% of patients with cholecystolithiasis. Cholecystolithiasis is a chronic recurrent hepatobiliary disease associated with impaired metabolism of cholesterol, bilirubin, and bile acids[1,2]. Age, sex, medications, diet, genetic factors, and factors associated with metabolic syndrome are risk factors for cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis[3]. Patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis may present with clinical symptoms, including chills, fever, jaundice, biliary obstruction, epigastric pain, and cirrhosis, which pose a serious threat to the patient’s quality of life[4]. At present, most patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis are treated surgically; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) combined with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), a minimally invasive, effective, and safe procedure, is the most common treatment[5,6]. In ERCP surgery, the papillary sphincter is incised by a duodenoscope to remove the choledocholithiasis. Then, the cholecystolithiasis is cleaned using retrieval balloons and basket catheters. LC is performed 2–7 days after ERCP. Although ERCP + LC is effective for patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis, this treatment has several disadvantages, including disruption of duodenal papilla function, a high risk of postoperative complications, and long operation times (OTs)[7,8]. Therefore, the development of new treatment options to improve patient experience and outcomes is needed.

The combination of LC and laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) as a minimally invasive surgery like ERCP + LC, and this treatment can effectively treat both cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis in one operation[9]. In the meta-analysis of Pan et al[10], LC + LCBDE ERCP + LC exhibited superior clinical efficacy and perioperative safety in patients with cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis compared with ERCP + LC. Furthermore, Lee[11] reported that LC + LCBDE is more suitable for elderly patients (over 80 years old) with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis than ERCP + LC, especially patients who have undergone gastrectomy with multiple large choledocholithiasis (≥ 15 mm) or patients who could not cooperate with endoscopic surgery. The LCBDE procedure involves dissection of the Calot’s triangle, incision of the gallbladder artery after clamping, choledochoscopic exploration and stone removal after cystic duct dissociation and incision, suture and reconstruction of the cystic duct, cholecystectomy, and drainage. LCBDE is as effective and safe as ERCP + LC. In addition, the total hospital stays are shorter and medical costs are lower for LCBDE compared with ERCP + LC[12]. In the present study, ERCP + LC is compared with LC + LCBDE to verify that LC + LCBDE is more suitable for patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis and propose an optimized scheme for the clinical management of this patient population.

This is a retrospective study, which included 243 patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis treated in The Affiliated Haixia Hospital of Huaqiao University (910th Hospital of Joint Logistic Support Force) between January 2019 and December 2023. The control group (n = 111) underwent ERCP + LC and the observation group (n = 132) underwent LC + LCBDE. The two groups were similar, with no significant differences in baseline clinical data (P > 0.05).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis by color Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging[13] and presented with recurrent epigastric pain and dyspepsia, including a history of preoperative right epigastric pain, complete medical records, and normal communi

The control group underwent ERCP + LC. After general anesthesia, ERCP was performed by duodenoscope to determine the dilatation of the biliary and cystic ducts and the condition of the gallbladder and common bile duct stones. After a small incision and large dilatation at the duodenal papilla, a guidewire was inserted into the common bile duct. The common bile duct stones were removed using a retrieval balloon and a basket catheter. Then, the guidewire was advanced into the dilated cystic duct and gallbladder to assist in inserting a retrieval balloon, and the gallbladder tube was slightly inflated. The retrieval balloon was used to assess the degree of dilation of the cystic duct and determine if the gallbladder stones can smoothly pass through the cystic duct into the common bile duct. The stones were dragged into the common bile duct and removed by the retrieval balloon or basket catheter. Larger stones were crushed and dragged into the common bile duct by the retrieval balloon or basket catheter. Stone removal was evaluated multiple times in conjunction with cholangiography. Then, the gallbladder was repeatedly rinsed under a microscope with a retrieval balloon to flush the residual small stones into the common bile duct. The stones dragged into the common bile duct by the retrieval balloons or basket catheters were removed. Cholangiography was performed again to evaluate gallbladder and choledocholithiasis removal, and the above steps were repeated if necessary. Postoperative drainage and irrigation were carried out via an indwelling nasobiliary catheter in the common bile duct. Two to seven days after ERCP, four- or three-port LC was performed under general anesthesia. The pneumoperitoneum pressure was maintained at 12–15 mmHg and a dorsal elevated and left oblique position. The gallbladder was pulled to the upper right to reveal the triangular structure. The anterior and posterior serosa of the triangle were dissected with an electric hook to reveal the cystic duct and the gallbladder artery. After identifying the structures of the three ducts, the cystic duct and the gallbladder artery were clamped with absorbable biological clips near the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct near the ampulla was clamped with titanium clips, and the cystic duct was cut between the two clips. The distal gallbladder artery was coagulated and the gallbladder bed was separated with the electric hook followed by gallbladder removal. A toothed grasper was placed under the xiphoid cannula to grasp the gallbladder neck, and the gallbladder was pulled into the cannula and taken out together with the cannula. An abdominal drainage tube was placed according to the intraoperative condition and removed 48 hours after surgery.

The observation group underwent LC + LCBDE. The LC with four ports was performed similarly to the control group. The Calot’s triangle was dissected, the gallbladder artery was clamped and cut off, and 10–15 mm of the cystic duct was freed. In patients with cystic duct diameters of ≥ 5 mm, the cystic duct was directly cut longitudinally and a choledochoscope was placed for exploration and stone removal. For patients with cystic duct diameters of < 5 mm, a small oblique incision was made at the junction of the cystic duct and common bile duct for exploration and stone removal by cholangioscopy; the cystic duct (4–5 mm) and the common bile (2–3 mm) duct were partially cut. The bile duct was explored up to the bifurcation of the common hepatic duct and down to the opening of the duodenal papilla. Smaller stones were directly removed, while larger stones were removed in pieces after crushing with a lithotripsy basket. After removing the stones, the bile duct incision was closed with 4-0 absorbable sutures and the cystic duct was reconstructed, followed by gallbladder dissection from the gallbladder bed and cholecystectomy. A drainage tube was placed through the foramen of Winslow, and a T-shaped tube was placed for drainage in patients with thinner common bile ducts and longer incisions and patients at risk of common bile duct stenosis.

Clinical efficacy was evaluated based on the surgical success rate and residual stone rate. Complications were evaluated based on the incidence of adverse reactions, including pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia, biliary tract infection (BTI), and bile leakage. Surgical indicators, including intraoperative blood loss (IBL) and OT, were recorded. Recovery indices, including postoperative exhaust/defecation time and length of hospital stays, were recorded. Serum inflammatory factors before and after surgery were measured. Fasting cubital venous blood (3 mL) was collected and centrifuged to obtain serum for the measurement of C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

Data are presented as means with standard errors. Independent samples and paired t-tests were employed for between-group and within-group (before and after treatment) comparisons. Count data are presented as n (%), and compared using χ2 tests. SPSS 23.0 was used for all statistical analyses, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

As shown in Table 1, no significant differences in age, sex, disease course, stone diameter, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were detected between the observation and control groups (P > 0.05).

| Data | Control group (n = 111) | Observation group (n = 132) | χ2/t | P value |

| Age (year) | 50.19 ± 8.93 | 49.80 ± 9.09 | 0.336 | 0.737 |

| Sex (male/female) | 70/41 | 88/44 | 0.344 | 0.557 |

| Disease course (months) | 4.25 ± 1.80 | 4.05 ± 1.77 | 0.871 | 0.385 |

| Choledocholithiasis (single/multiple) | 64/47 | 73/59 | 0.136 | 0.712 |

| Hypertension (with/without) | 39/72 | 43/89 | 0.177 | 0.674 |

| Diabetes mellitus (with/without) | 15/96 | 28/104 | 2.454 | 0.117 |

| Type of stones (cholesterol gallstones/pigment gallstones) | 72/39 | 96/36 | 1.747 | 0.186 |

As shown in Table 2, the surgical success and residual stone rates were 95.45% and 1.52%, respectively, for the observation group and 92.79% and 3.60%, respectively, for the control group. No significant differences in surgical success or residual stone rates were detected between the observation and control groups (P > 0.05).

| Indicators | Control group (n = 111) | Observation group (n = 132) | χ2 | P value |

| Surgical success rate | 103 (92.79) | 126 (95.45) | 0.787 | 0.375 |

| Residual stone rate | 4 (3.60) | 2 (1.52) | 1.092 | 0.296 |

Both groups experienced mild complications, including pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia, BTI, and bile leakage (Table 3). The total complication rate was significantly lower in the observation group compared with the complication rate in the control group (13.51% vs 5.30%, P < 0.05).

| Indicators | Control group (n = 111) | Observation group (n = 132) | χ2 | P value |

| Pancreatitis | 3 (2.70) | 2 (1.52) | ||

| Hyperamylasemia | 8 (7.21) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Biliary tract infection | 4 (3.60) | 2 (1.52) | ||

| Bile leakage | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.27) | ||

| Total | 15 (13.51) | 7 (5.30) | 4.937 | 0.026 |

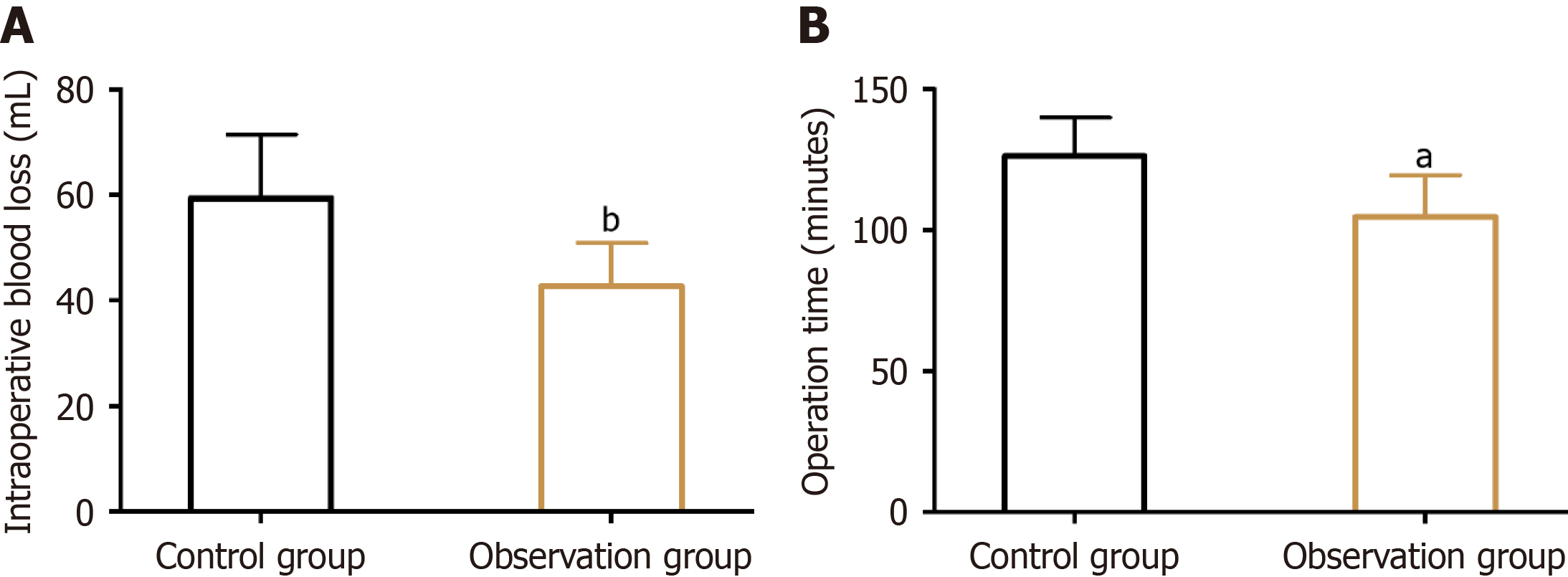

Incision size was smaller, the IBL was lower (59.35 ± 12.09 mL vs 42.77 ± 8.13 mL, P < 0.05), and the OT was shorter (126.28 ± 13.63 minutes vs 104.73 ± 14.86 minutes, P < 0.05) in the observation group compared with the control group (P < 0.05; Figure 1).

Postoperative exhaust (27.33 ± 3.75 hours vs 21.84 ± 4.54 hours, P < 0.05) and defecation (34.64 ± 7.49 hours vs 27.35 ± 5.80 hours, P < 0.05) times and hospital stays (11.93 ± 3.16 days vs 8.99 ± 2.54 days, P < 0.05) were significantly shorter in the observation group compared with the times in the control group (Figure 2).

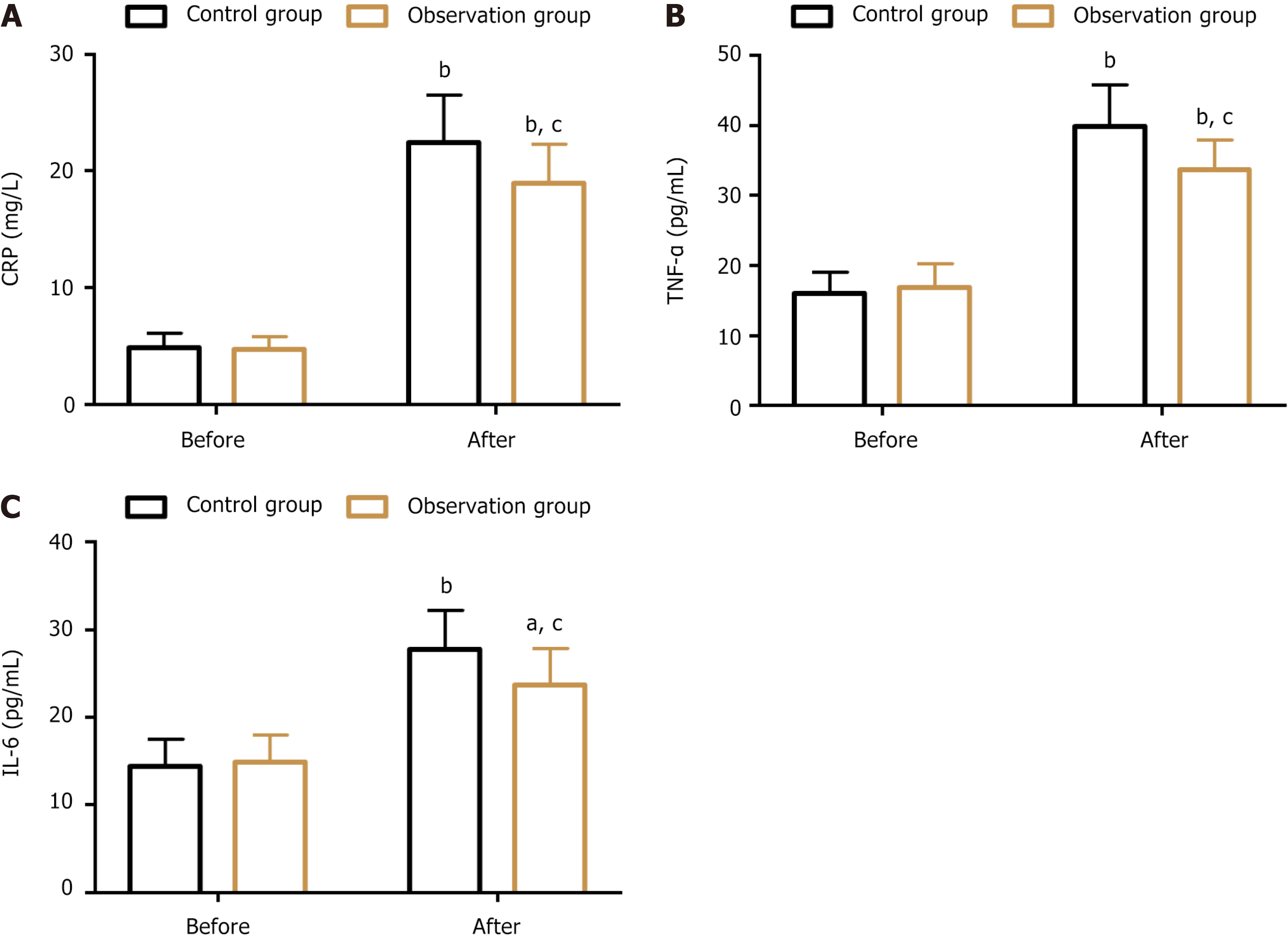

Changes in serum inflammatory factors are shown in Figure 3. CRP levels in the control and observation groups were 4.90 ± 1.22 mg/L and 4.75 ± 1.08 mg/L before treatment, and 22.41 ± 4.09 mg/L and 18.95 ± 3.33 mg/L after treatment, respectively. The pre-treatment TNF-α levels in the control and observation groups were 16.08 ± 2.98 pg/mL and 16.81 ± 3.4 pg/mL, respectively; the TNF-α levels increased to 39.84 ± 5.87 pg/mL and 33.63 ± 4.3 pg/mL, respectively, after treatment. The IL-6 Levels were 14.39 ± 3.14 pg/mL in the control group and 14.86 ± 3.12 pg/mL in the observation group before treatment. The IL-6 Levels increased to 27.79 ± 4.35 pg/mL in the control group and 23.73 ± 4.15 pg/mL in the observation group after treatment. No significant differences in serum inflammatory indices were detected between the two groups before treatment (P > 0.05). However, the serum inflammatory indices were significantly lower in the observation group compared with the control group after treatment (P < 0.05).

In this study, outcomes of patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis who underwent ERCP + LC (control group) were compared with the outcomes in patients who underwent LC + LCBDE (observation group). Clinical efficacy was similar between the two groups and safety, surgical indicators, recovery indices, and serum inflammatory factors were better after LC + LCBDE compared with ERCP + LC.

The clinical efficacy was assessed based on the surgical success rate and residual stone rate. These two indices of clinical efficacy were equivalent in the two groups, suggesting that LC + LCBDE exhibits comparable clinical efficacy to ERCP + LC. In a study of patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis by Guo et al[14], LC + LCBDEERCP + LC stone clearance rates were similar in patients who underwent LC + LCBDE and patients who underwent ERCP + LC, similar to our findings. In the past, open cholecystectomy and biliary T-tube drainage were the main treatment options for patients with cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis; these approaches resulted in large surgery-related wounds and postoperative complication risks that impeded postoperative recovery[15,16]. In the ERCP + LC procedure, common bile duct incisions can be avoided to maximize protection of biliary function[17]. The LC + LCBDE approach prevents BTI and bile leakage. In addition, by evaluating the diameter of the cystic duct, the most appropriate incision location and size can be selected to minimize the impact on the common bile duct and reduce the risk of common bile duct stenosis[6,18,19].

The safety of the two procedures was evaluated based on the incidence of complications, including pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia, BTI, and bile leakage. The total complication rate was lower in the observation group, indicating that LC + LCBDE is safer than ERCP + LC. Vinish et al[20] demonstrated that LC + LCBDE cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis can be effectively treated with a high safety profile using the LC + LCBDE approach, consistent with our results. Ji et al[21] also showed that LC + LCBDE is associated with a lower risk of biliary leakage, similar to our findings. The relatively high risk of postoperative complications related to ERCP + LC may be due to the sphincter of Oddi incision during the surgical procedure, which may cause changes in the biliary tract structure that negatively affect the natural defense mechanism of the bile duct, leading to adverse events, such as pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia, BTI, and bile leakage[22,23]. The LC + LCBDE approach, as a one-time operation, circumvents the high surgical risk of two procedures in the ERCP + LC approach and preserves duodenal papilla function, thus avoiding the structural changes to the bile duct related to the papillotomy and infections caused by retrograde flow of intestinal juice[24,25].

IBL was lower and OTs, postoperative exhaust/defecation times, and hospital stays were shorter in the observation group, suggesting that the LC + LCBDE approach results in faster postoperative rehabilitation in patients with cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis. This may be attributed to the high first-time success rate of the LC + LCBDE procedure and the low risk of postoperative complications. Furthermore, serum inflammatory factors, including CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6, were lower in the observation group compared with the control group after treatment, suggesting that inflammation is lower in patients who underwent LC + LCBDE.

There are several limitations to this study. First, long-term follow-up and prognostic analyses were not performed, and supplementation would be beneficial to understand the prognostic impact of the two surgical regimens. Second, the effects of LC + LCBDE on patient quality of life were not analyzed. Analyzing the patient quality of life can increase our understanding of the specific impact of this therapy on patients. Third, further analysis of the factors influencing complications can lead to optimal patient management.

While LC + LCBDE and ERCP + LC have similar clinical efficacies, LC + LCBDE is associated with fewer postoperative complications, less inflammation, and faster recoveries. Our findings provide a reliable clinical reference for the selection of better treatments for patients with cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis.

| 1. | Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, Diamond T, Taylor MA. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD003327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu Y, Xu CJ, Xu SF. Advances in Risk Factors for Recurrence of Common Bile Duct Stones. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:1067-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Genet D, Souche R, Roucaute S, Borie F, Millat B, Valats JC, Fabre JM, Herrero A. Upfront Laparoscopic Management of Common Bile Duct Stones: What Are the Risk Factors of Failure? J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;27:1846-1854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yin Y, He K, Xia X. Comparison of Primary Suture and T-Tube Drainage After Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration Combined with Intraoperative Choledochoscopy in the Treatment of Secondary Common Bile Duct Stones: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2022;32:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pavlidis ET, Pavlidis TE. Current management of concomitant cholelithiasis and common bile duct stones. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Lan WF, Li JH, Wang QB, Zhan XP, Yang WL, Wang LT, Tang KZ. Comparison of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography combined with laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with gallbladder and common bile duct stones a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27:4656-4669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wu K, Xiao L, Xiang J, Huan L, Xie W. Is early laparoscopic cholecystectomy after clearance of common bile duct stones by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography superior?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bostanci EB, Ercan M, Ozer I, Teke Z, Parlak E, Akoglu M. Timing of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography with sphincterotomy: a prospective observational study of 308 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:661-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bosley ME, Ganapathy AS, Sanin GD, Cambronero GE, Neff LP, Syriani FA, Gaffley MW, Evangelista ME, Westcott CJ, Miller PR, Nunn AM. Reclaiming the management of common duct stones in acute care surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95:524-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pan L, Chen M, Ji L, Zheng L, Yan P, Fang J, Zhang B, Cai X. The Safety and Efficacy of Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration Combined with Cholecystectomy for the Management of Cholecysto-choledocholithiasis: An Up-to-date Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2018;268:247-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee SE. One-stage versus two-stage approach for concomitant gallbladder and common bile duct stones: which one is more proper in patients over 80 years old? J Minim Invasive Surg. 2022;25:7-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, Mackersie RC, Rodas A, Kreuwel HT, Harris HW. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg. 2010;145:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Manes G, Paspatis G, Aabakken L, Anderloni A, Arvanitakis M, Ah-Soune P, Barthet M, Domagk D, Dumonceau JM, Gigot JF, Hritz I, Karamanolis G, Laghi A, Mariani A, Paraskeva K, Pohl J, Ponchon T, Swahn F, Ter Steege RWF, Tringali A, Vezakis A, Williams EJ, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51:472-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guo T, Wang L, Xie P, Zhang Z, Huang X, Yu Y. Surgical methods of treatment for cholecystolithiasis combined with choledocholithiasis: six years' experience of a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:4903-4911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhen W, Xu-Zhen W, Nan-Tao F, Yong L, Wei-Dong X, Dong-Hui Z. Primary Closure Versus T-Tube Drainage Following Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration in Patients With Previous Biliary Surgery. Am Surg. 2021;87:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shojaiefard A, Esmaeilzadeh M, Khorgami Z, Sotoudehmanesh R, Ghafouri A. Assessment and treatment of choledocholithiasis when endoscopic sphincterotomy is not successful. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:275-278. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Li MK, Tang CN, Lai EC. Managing concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones in the laparoscopic era: a systematic review. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Li T, Cheng B, Jin X. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration plus cholecystectomy versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography plus laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholecystocholedocholithiasis: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3275-3286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang XX, Wu JY, Bai YN, Wu JY, Lv JH, Chen WZ, Huang LM, Huang RF, Yan ML. Outcomes of laparoscopic bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis with small common bile duct. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:1803-1813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vinish DB, Krishnamurthy G, Radhakrishna P, Sarangapani A, Ganesan S, Ramas J, Kalyanasundaram R, Ramakrishna BS. Endoscopic Stone Extraction followed by Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in Tandem for Concomitant Cholelithiasis and Choledocholithiasis: A Prospective Study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ji H, Hou Y, Cheng X, Zhu F, Wan C, Fang L. Association of Laparoscopic Methods and Clinical Outcomes of Cholecystolithiasis Plus Choledocholithiasis: A Cohort Study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023;34:35-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen CC, Wu SD, Tian Y, Siwo EA, Zeng XT, Zhang GH. Sphincter of Oddi-preserving and T-tube-free laparoscopic management of extrahepatic bile duct calculi. World J Surg. 2011;35:2283-2289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rauh JL, Ganapathy AS, Bosley ME, Rangecroft A, Zeller KA, Sieren LM, Petty JK, Pranikoff T, Neff LP. Making common duct exploration common-balloon sphincteroplasty as an adjunct to transcystic laparoscopic common bile duct exploration for pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2023;58:94-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bove A, Di Renzo RM, Palone G, Testa D, Malerba V, Bongarzoni G. Single-stage procedure for the treatment of cholecysto-choledocolithiasis: a surgical procedures review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pallaneeandee NK, Govindan SS, Zi Jun L. Evaluation of the Common bile duct (CBD) Diameter After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (LC) and Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration (LCBDE): A Retrospective Study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2023;33:62-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |