Published online Jun 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i6.1926

Revised: April 11, 2024

Accepted: April 22, 2024

Published online: June 27, 2024

Processing time: 145 Days and 18.1 Hours

The treatment of postoperative anastomotic stenosis after excision of rectal cancer is challenging. Endoscopic balloon dilation and radial incision are not effective in all patients. We present a new endoscopy-assisted magnetic compression technique (MCT) for the treatment of rectal anastomotic stenosis. We successfully applied this MCT to a patient who developed an anastomotic stricture after radical resection of rectal cancer.

A 50-year-old man had undergone laparoscopic radical rectal cancer surgery at a local hospital 5 months ago. A colonoscopy performed 2 months ago indicated that the rectal anastomosis was narrow due to which ileostomy closure could not be performed. The patient came to the Magnetic Surgery Clinic of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University after learning that we had successfully treated patients with colorectal stenosis using MCT. We performed endoscopy-assisted magnetic compression surgery for rectal stenosis. The magnets were removed 16 d later. A follow-up colonoscopy performed after 4 months showed good anastomotic patency, following which, ileostomy closure surgery was performed.

MCT is a simple, non-invasive technique for the treatment of anastomotic stricture after radical resection of rectal cancer. The technique can be widely used in clinical settings.

Core Tip: Endoscopic balloon dilation and radial incision are commonly used for the treatment of postoperative anastomotic stenosis after surgery for colorectal cancer, but the effect is limited. Magnetic compression technique (MCT) can be used for anastomosis of various parts of the digestive tract. Cases of postoperative anastomotic stricture after colorectal cancer surgery treated by MCT have been rarely reported. We report a patient with low rectal anastomosis who was successfully treated with the MCT. This case report enriches the treatment methods of postoperative anastomotic stenosis of colorectal cancer, which can bring important reference significance for peers.

- Citation: Zhang MM, Sha HC, Xue HR, Qin YF, Song XG, Li Y, Li Y, Deng ZW, Gao YL, Dong FF, Lyu Y, Yan XP. Novel magnetic compression technique for the treatment of postoperative anastomotic stenosis in rectal cancer: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(6): 1926-1932

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i6/1926.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i6.1926

The incidence of postoperative anastomotic stenosis following colorectal cancer surgery is relatively low, however, it poses challenges in terms of treatment. Risk factors for anastomotic stenosis include anastomotic leakage, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, gender, postoperative radiotherapy, and anastomotic ischemia[1-5]. The occurrence of anastomotic stenosis precludes the possibility of enterostomy reduction surgery, which adversely affects the quality of life of patients. Endoscopic balloon dilation and radial incision are effective in some patients[6-8], but some patients show poor outcomes. Therefore, the development of effective treatment for postoperative anastomotic stenosis after colorectal cancer surgery is imperative to improve the quality of life of patients. Magnetic compression technique (MCT) is a new surgical technique that can achieve suture-free anastomosis of the digestive tract by leveraging the magnetic force between magnets[9,10]. MCT in combination with endoscopic technique has been used for the treatment of biliary stricture[11-14], ureteral stricture[15,16], and esophageal stricture[17-20]. It has the advantages of simple operation, minimal trauma, and a good therapeutic effect. However, the application of MCT in postoperative anastomotic stenosis after colorectal cancer surgery has rarely been reported. This case report describes the successful use of MCT for the treatment of postoperative anastomotic stricture after radical surgery for rectal cancer.

A 50-year-old man presented with a narrow rectal anastomosis which was discovered 2 months ago during a follow-up colonoscopy following rectal cancer surgery.

The patient had undergone laparoscopic radical resection for rectal cancer 5 months ago. A narrow rectal anastomosis was detected 2 months ago during colonoscopy.

He was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 5 months ago and his blood sugar has been effectively managed by oral hypoglycemic drugs.

His family history was unremarkable.

Initial physical examination revealed no cardiovascular or respiratory abnormalities. The abdomen was flat and non-tender. An ileostomy was seen on the right side of the abdomen.

The hematology results were normal.

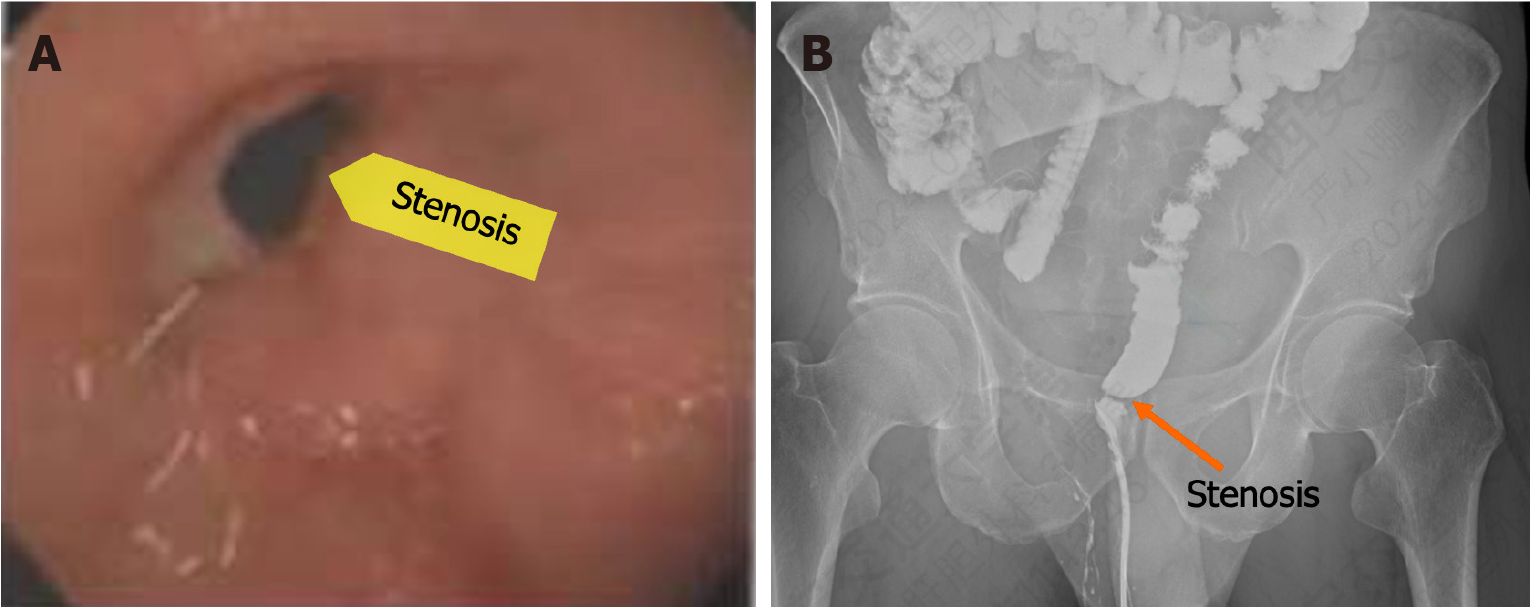

During colonoscopy, a narrow rectal anastomosis located 2 cm above the anus was observed, with a diameter of approximately 5 mm. Anastomotic staples were still present at the site, and the colonoscope could not pass through the narrow rectal anastomosis (Figure 1A). Subsequent, colonography confirmed a stenosis in the lower rectum (Figure 1B).

Based on the colonoscopy and colonography, the diagnosis of rectal anastomosis stenosis was established.

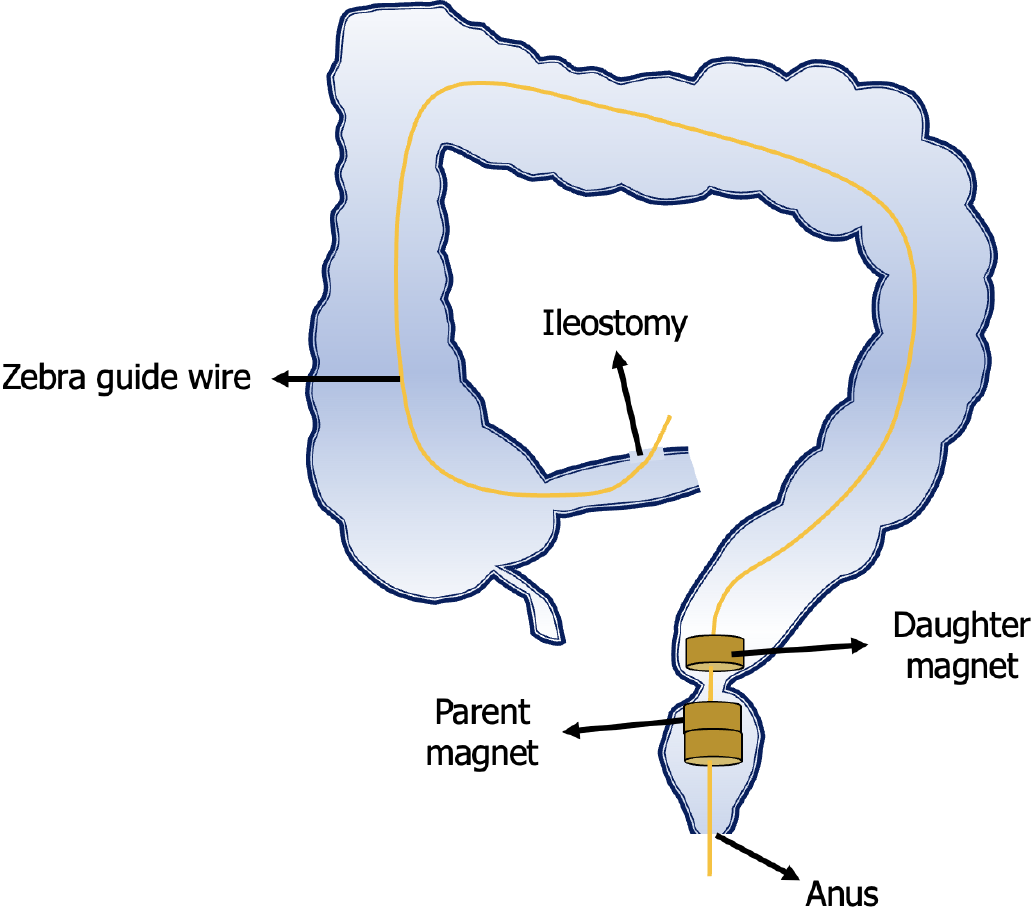

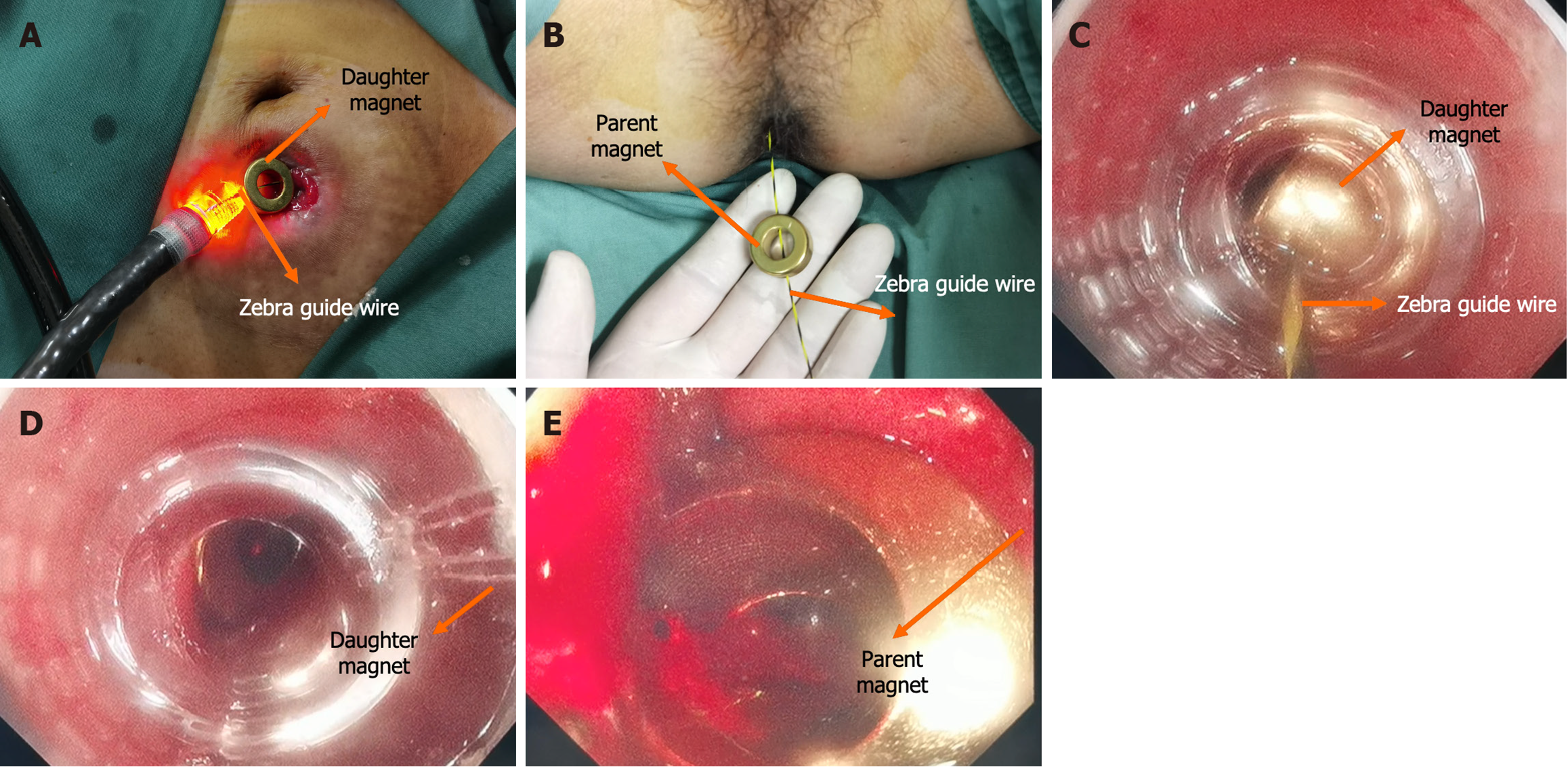

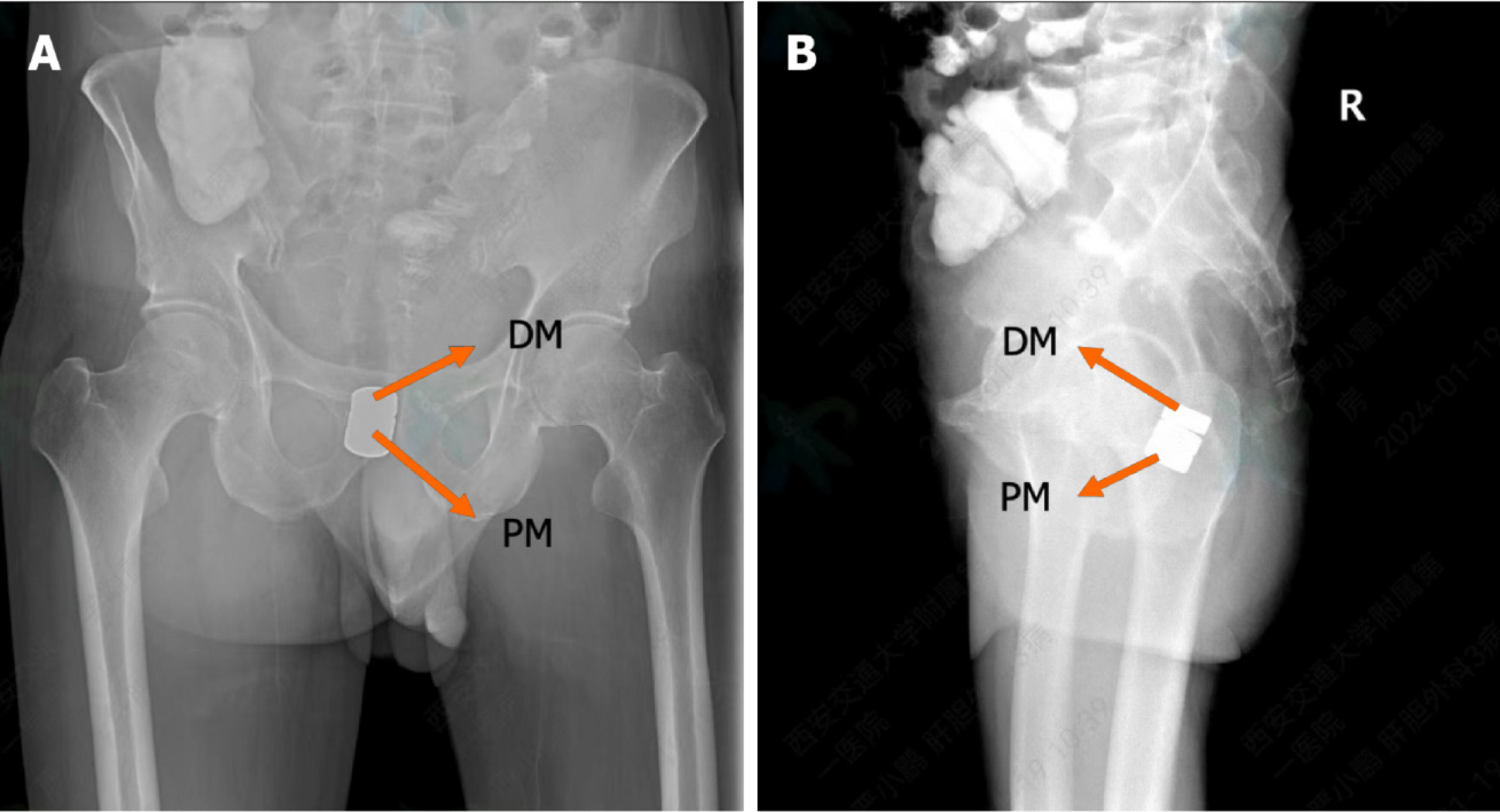

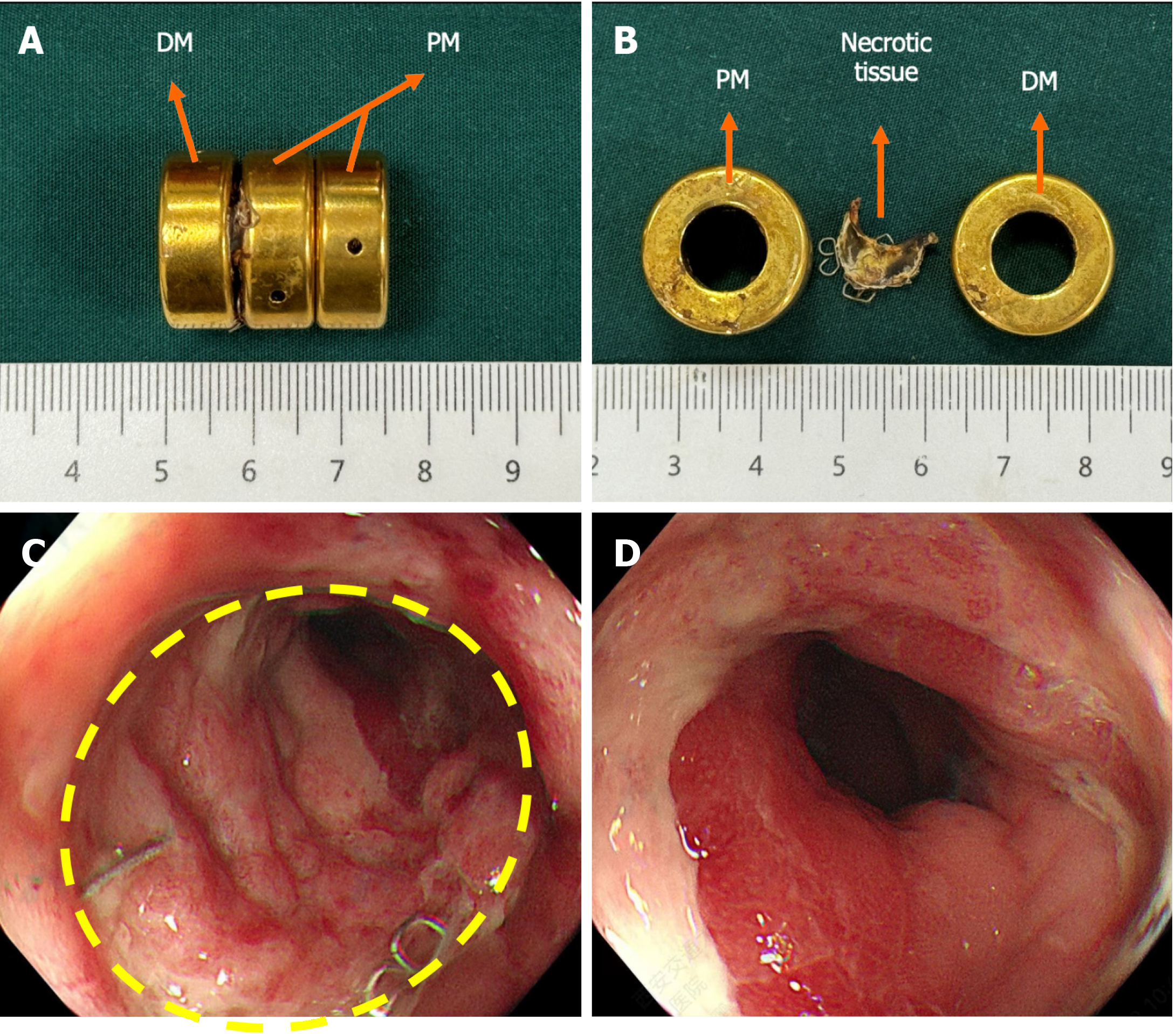

The surgical plan developed by the Multi-disciplinary team of Magnetic Surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University was shown in Figure 2. The patient and his family members provided written informed consent for the operation. The patient was positioned supine following intravenous anesthesia. Enteroscopy was conducted via the ileostomy, reaching the proximal end of the rectal anastomosis. A zebra guide wire was passed through biopsy hole of the colonoscope, and its tip was pulled out through the narrow section of the rectum via the anus. The zebra wire was left in place while the colonoscope was witdrawn. The zebra guide wire located on the side of the ileostomy was passed through the side hole of the daughter magnet and then retrogradely advanced through the biopsy hole of the colonoscope (Figure 3A). The zebra guide wire on the anal side was passed through the side hole of the parent magnet (Figure 3B). The colonoscope was advanced through the ileostomy and pushed the daughter magnet along the zebra guide wire to the proximal end of the rectal anastomosis (Figure 3C). The parent magnet along the zebra guide wire was pushed through the anus. The daughter magnet and the parent magnet were automatically attracted together, following which the zebra guide wire was exited. To increase the magnetic force between the daughter and the parent magnets, another magnet was introduced through the anus. Colonoscopy was performed again through ileostomy and anus to observe the status of daughter magnet and parent magnets (Figures 3D and E). The x-ray examination showed close apposition of the daughter and the parent magnets (Figures 4). Sixteen days after surgery, the daughter and the parent magnets were expelled through the anus (Figure 5A and B). Colonoscopy showed the new anastomosis, and the colonoscope passed smoothly (Figures 5C and D).

Following discharge, the patient insisted on anal dilation treatment using a 20 mm diameter anal dilator. Four months later, the rectal anastomosis remained good patent, and the ileostomy was successfully closed. The patient experienced normal bowel movements postoperatively.

Hyperplasia of the scar tissue is the main pathological cause of anastomotic stenosis after colorectal cancer surgery. Endoscopic balloon dilation and radial incision cannot effectively remove hyperplastic scars, and may even aggravate scar formation. Therefore, there are limited options for the treatment of postoperative anastomotic stenosis of colorectal cancer[6]. The unique anastomotic principle of the MCT makes it effective in treating anastomotic stenosis after operation for colorectal cancer. Firstly, in the treatment of rectal anastomotic stenosis by MCT, the scar of anastomotic hyperplasia is located between the magnets. The continuous magnetic compression induces the pathological change sequence of ischemia-necrosis-shedding[21]. The primary distinction between MCT and other methods like balloon dilation and radial incision lies in the removal of scar tissue. Secondly, MCT does not involve inserting foreign objects into the intestinal wall during the establishment of the anastomosis, reducing the risk of complications such as fistula and infection, further reducing the formation of anastomotic scar. Third, by combining MCT with endoscopic techniques, minimally invasive anastomosis can be achieved, avoiding the trauma and complications associated with traditional surgical procedures.

The present case has some similarities with the previously reported cases where the MCT was used to treat postoperative anastomotic stenosis. However, there are some noteworthy novel aspects of this case. First, the patient had an ileostomy that provided access for the insertion of the daughter magnet. Second, zebra guides wire can pass through the narrow rectal anastomosis, and we chose magnets with holes on the side, which facilitated the placement of magnets. Third, to increase the magnetic force between the daughter magnet and the parent magnet, we inserted two magnets from the anus to act as the parent magnet. Fourth, unlike previous cases, the rectal anastomosis in this patient was near the anus, and there was a risk of anal damage during the magnetic compression process. However, the final results showed that the function of the anus was well maintained. This demonstrated that even if the anastomotic position is very low, the use of MCT does not affect anal function.

MCT combined with endoscopic technology can be used for the treatment of postoperative anastomotic stenosis after colorectal cancer surgery. It has the advantages of simple operation, minimal trauma, and good anastomotic patency, making it worthy of widespread clinical application.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Milosavljevic VM, Serbia S-Editor: Luo ML L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Cong J, Zhang H, Chen C. Definition and grading of anastomotic stricture/stenosis following low anastomosis after total mesorectal excision: A single-center study. Asian J Surg. 2023;46:3722-3726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Brandt LJ, Feuerstadt P, Longstreth GF, Boley SJ; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: epidemiology, risk factors, patterns of presentation, diagnosis, and management of colon ischemia (CI). Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:18-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bannura GC, Cumsille MA, Barrera AE, Contreras JP, Melo CL, Soto DC. Predictive factors of stenosis after stapled colorectal anastomosis: prospective analysis of 179 consecutive patients. World J Surg. 2004;28:921-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kirat HT, Kiran RP, Lian L, Remzi FH, Fazio VW. Influence of stapler size used at ileal pouch-anal anastomosis on anastomotic leak, stricture, long-term functional outcomes, and quality of life. Am J Surg. 2010;200:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee SY, Kim CH, Kim YJ, Kim HR. Anastomotic stricture after ultralow anterior resection or intersphincteric resection for very low-lying rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:660-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim PH, Song HY, Park JH, Kim JH, Na HK, Lee YJ. Safe and effective treatment of colorectal anastomotic stricture using a well-defined balloon dilation protocol. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:675-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bravi I, Ravizza D, Fiori G, Tamayo D, Trovato C, De Roberto G, Genco C, Crosta C. Endoscopic electrocautery dilation of benign anastomotic colonic strictures: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:229-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kawaguti FS, Martins BC, Nahas CS, Marques CF, Ribeiro U, Nahas SC, Maluf-Filho F. Endoscopic radial incision and cutting procedure for a colorectal anastomotic stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:408-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wall J, Diana M, Leroy J, Deruijter V, Gonzales KD, Lindner V, Harrison M, Marescaux J. MAGNAMOSIS IV: magnetic compression anastomosis for minimally invasive colorectal surgery. Endoscopy. 2013;45:643-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gagner M, Abuladze D, Koiava L, Buchwald JN, Van Sante N, Krinke T. First-in-Human Side-to-Side Magnetic Compression Duodeno-ileostomy with the Magnet Anastomosis System. Obes Surg. 2023;33:2282-2292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ödemiş B, Başpınar B, Tola M, Torun S. Magnetic Compression Anastomosis Is a Good Treatment Option for Patients with Completely Obstructed Benign Biliary Strictures: A Case Series Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4906-4918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Do MY, Jang SI, Cho JH, Joo SM, Lee DK. Magnetic compression anastomosis for treatment of biliary stricture after cholecystectomy. VideoGIE. 2022;7:253-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jang SI, Cho JH, Lee DK. Magnetic Compression Anastomosis for the Treatment of Post-Transplant Biliary Stricture. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:266-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jang SI, Lee KH, Joo SM, Park H, Choi JH, Lee DK. Maintenance of the fistulous tract after recanalization via magnetic compression anastomosis in completely obstructed benign biliary stricture. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1393-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | An Y, Zhang M, Xu S, Deng B, Shi A, Lyu Y, Yan X. An experimental study of magnetic compression technique for ureterovesical anastomosis in rabbits. Sci Rep. 2023;13:1708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shlomovitz E, Copping R, Swanstrom LL. Magnetic Compression Anastomosis for Recanalization of Complete Ureteric Occlusion after Radical Cystoprostatectomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34:1640-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Krishnan N, Pakkasjärvi N, Kainth D, Danielson J, Verma A, Yadav DK, Goel P, Anand S. Role of Magnetic Compression Anastomosis in Long-Gap Esophageal Atresia: A Systematic Review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33:1223-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Evans LL, Chen CS, Muensterer OJ, Sahlabadi M, Lovvorn HN, Novotny NM, Upperman JS, Martinez JA, Bruzoni M, Dunn JCY, Harrison MR, Fuchs JR, Zamora IJ. The novel application of an emerging device for salvage of primary repair in high-risk complex esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2022;57:810-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Holler AS, König TT, Chen C, Harrison MR, Muensterer OJ. Esophageal Magnetic Compression Anastomosis in Esophageal Atresia Repair: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review and Comparison with a Novel Approach. Children (Basel). 2022;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sterlin A, Evans L, Mahler S, Lindner A, Dickmann J, Heimann A, Sahlabadi M, Aribindi V, Harrison MR, Muensterer OJ. An experimental study on long term outcomes after magnetic esophageal compression anastomosis in piglets. J Pediatr Surg. 2022;57:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang M, Lyu X, Zhao G, An Y, Lyu Y, Yan X. Establishment of Yan-Zhang's staging of digestive tract magnetic compression anastomosis in a rat model. Sci Rep. 2022;12:12445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |