Published online Jun 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i6.1609

Revised: April 11, 2024

Accepted: April 26, 2024

Published online: June 27, 2024

Processing time: 131 Days and 1.3 Hours

Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) is a surgical procedure for treating pancreatic cancer; however, the risk of complications remains high owing to the wide range of organs involved during the surgery and the difficulty of anastomosis. Pancreatic fistula (PF) is a major complication that not only increases the risk of postoperative infection and abdominal hemorrhage but may also cause multi-organ failure, which is a serious threat to the patient’s life. This study hypothesized the risk factors for PF after LPD.

To identify the risk factors for PF after laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy in patients with pancreatic cancer.

We retrospectively analyzed the data of 201 patients admitted to the Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center between August 2022 and August 2023 who underwent LPD for pancreatic cancer. On the basis of the PF’s incidence (grades B and C), patients were categorized into the PF (n = 15) and non-PF groups (n = 186). Differences in general data, preoperative laboratory indicators, and surgery-related factors between the two groups were compared and analyzed using multifactorial logistic regression and receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses.

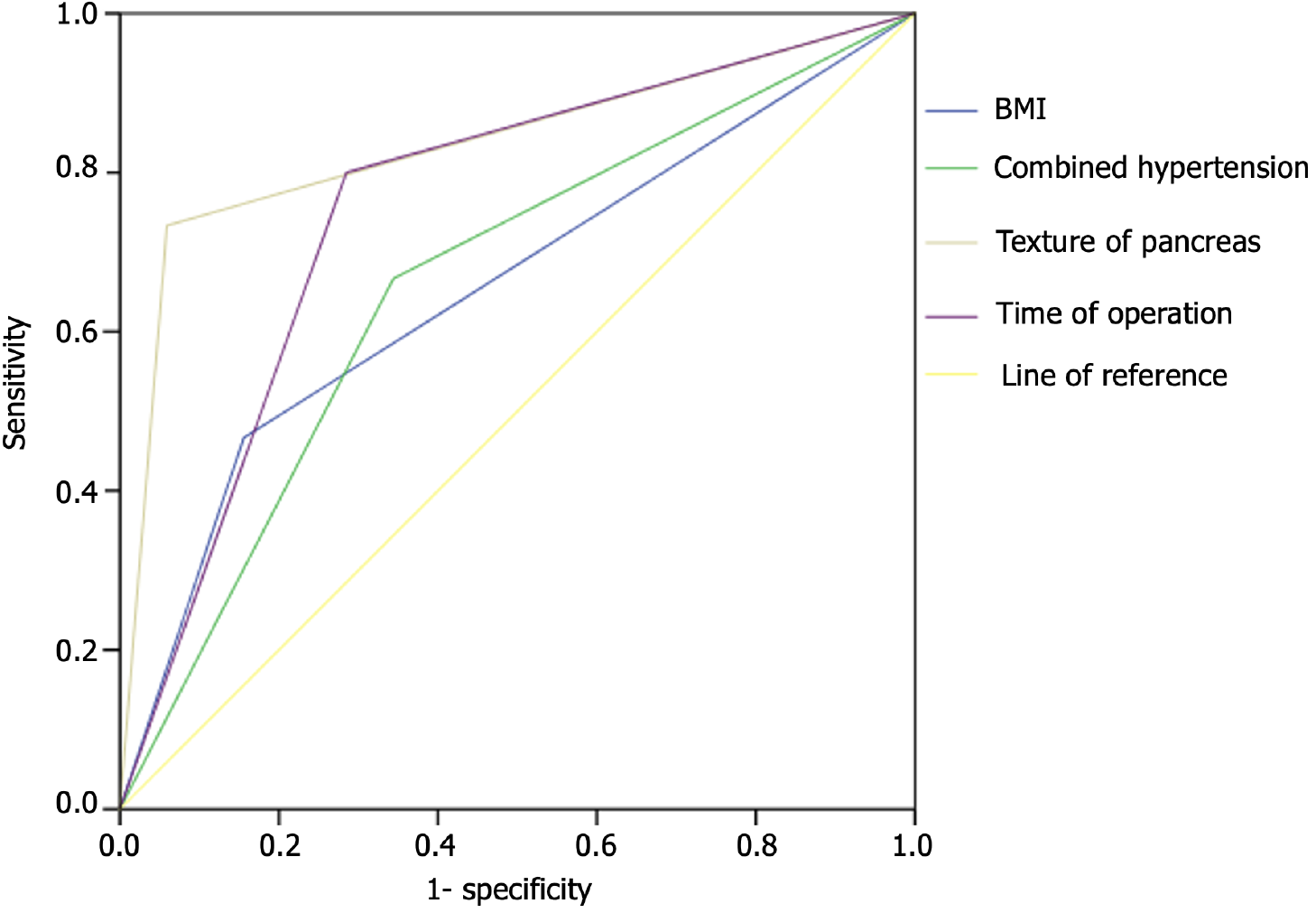

The proportions of males, combined hypertension, soft pancreatic texture, and pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm; surgery time; body mass index (BMI); and amylase (Am) level in the drainage fluid on the first postoperative day (Am > 1069 U/L) were greater in the PF group than in the non-PF group (P < 0.05), whereas the preoperative monocyte count in the PF group was lower than that in the non-PF group (all P < 0.05). The logistic regression analysis revealed that BMI > 24.91 kg/m² [odds ratio (OR) =13.978, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.886-103.581], hypertension (OR = 8.484, 95%CI: 1.22-58.994), soft pancreatic texture (OR = 42.015, 95%CI: 5.698-309.782), and operation time > 414 min (OR = 15.41, 95%CI: 1.63-145.674) were risk factors for the development of PF after LPD for pancreatic cancer (all P < 0.05). The areas under the ROC curve for BMI, hypertension, soft pancreatic texture, and time prediction of PF surgery were 0.655, 0.661, 0.873, and 0.758, respectively.

BMI (> 24.91 kg/m²), hypertension, soft pancreatic texture, and operation time (> 414 min) are considered to be the risk factors for postoperative PF.

Core Tip: Controlling the highly correlated risk factors of pancreatic fistula (PF) following laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) can decrease PF incidence. Although existing studies have confirmed that the occurrence of PF after LPD is influenced by various factors, including self-development and surgery-related factors, few studies have examined the factors influencing the development of PF after LPD in pancreatic cancer. Here, we analyzed the factors associated with the development of PF after LPD for pancreatic cancer and found that body mass index (> 24.91 kg/m²), hypertension, soft pancreatic texture, and operation time (> 414 min) were risk factors.

- Citation: Xu H, Meng QC, Hua J, Wang W. Identifying the risk factors for pancreatic fistula after laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(6): 1609-1617

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i6/1609.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i6.1609

Pancreatic cancer is characterized by rapid progression, high malignancy, and poor prognosis. Pancreatic cancer is not sensitive to chemotherapy; therefore, surgical removal is the only effective treatment for patients to achieve long-term survival[1]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is frequently used in the treatment of pancreatic cancer, and it is the most complex clinical surgery involving the viscera and anatomical structures[2]. Following the advancements in minimally invasive technology, laparoscopic surgeries have been increasingly used in clinical PD, with significantly improved safety and reduced mortality[3]. However, owing to the wide range of organs involved in the operation and the difficulty of anastomosis, the risk of complications remains high. Pancreatic fistula (PF) is one of the main complications of laparoscopic PD (LPD). The flow of pancreatic fluid into the abdominal cavity can corrode abdominal organs, provide conditions for bacterial proliferation, and increase the probability of postoperative infection, bleeding, and secondary sepsis, leading to death[4]. Controlling the highly correlated risk factors of PF after LPD and implementing targeted measures can reduce the probability of PF and alleviate its symptoms. Although current studies have confirmed that the occurrence of PF after LPD is influenced by various factors, including developmental, environmental, and surgical-related factors[5-7], few studies have focused on the factors influencing PF after LPD in patients with pancreatic cancer. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze PF’s risk factors after LPD in patients with pancreatic cancer and serve as a basis for clinical prevention and treatment.

The case data of 201 patients with pancreatic cancer, who underwent LPD at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center between August 2022 and August 2023, were retrospectively analyzed. The entry criteria were as follows: (1) Diagnosis confirmed by physical examination, ultrasound examination, and pathological examination in accordance with the diagnostic standards for pancreatic cancer in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines[8]; (2) Line of LPD surgery without LPD contraindication; and (3) Complete clinical information. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Abnormal coagulation function; (2) Combined cardiopulmonary liver and kidney dysfunction; (3) Transfer to the open abdomen during surgery for various reasons; (4) Immunosuppressive diseases; and (5) Distant metastasis.

All surgeries were performed in our department by surgeons with senior professional titles. Preoperative blood clotting and liver and kidney function tests were the routine biochemical examinations. After general anesthesia was achieved, the internal jugular vein catheter was inserted. After the pneumoperitoneum was established, a laparoscope was first placed in it. A 12-mm incision was made below the patient’s navel and a 12-mm tubular channel (trocar) was inserted. Further, the incisions were located 2 cm above the junction of the right mid-clavicular line and the level of the navel and 1 cm beneath the junction of the right anterior armpit line and the lower edge of the ribs. Trocars measuring 10 and 12 mm were placed. The abdominal cavity was laparoscopically examined and the superior mesenteric vein was exposed; the associated ligaments were detached; the jejunum was cut; and the distal stomach, pancreas, gallbladder, hepatic duct, and gallbladder were removed. During the process, it is important to pay attention to ligation of the common hepatic artery and other vessels, clean the lymph nodes, irrigate the abdominal cavity after excision, and re-establish pneumoperitoneum for routine gastrointestinal (GI) reconstruction. Next, the drainage tube was placed behind the biliary-intestinal anastomosis and in front of the pancreato-intestinal anastomosis and the fixed. After the laparoscope and other equipment were withdrawn, the abdominal cavity was closed layer by layer to complete the operation.

Diagnostic criteria for PF: The definition of PF per the diagnostic criteria of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula[9] includes fluid drainage from anastomosis or pancreatic stump (> 10 mL/d) on or after postoperative day 3 and drainage fluid amylase (Am) level exceeding more than three times the maximum normal value of plasma Am for > 3 d consecutively. It also includes the presence of clinical signs such as fever, fluid accumulation surrounding the anastomosis on ultrasound or computed tomography imaging examination, and puncture biopsy-proven Am levels in fluid three times higher than the normal maximum for plasma Am. According to the different clinical manifestations of the classification standard of PF, grade A (no clinical significance) was observed in PF, which does not have any adverse clinical consequences; it is defined as an Am level in the drainage fluid 3 days or more after surgery that is 3 times higher than the upper limit of the normal serum Am concentration, but does not require any clinical treatment or only minimal treatment (e.g., only drainage tube placement). Grade B was clinically significant and curable PF, which will affect the patient’s postoperative rehabilitation process and require symptomatic treatment and adequate drainage, with a relatively increased length of hospital stay; it is usually accompanied by a certain degree of signs of infection, such as an elevated white blood cell count and low fever, and it may require antimicrobial therapy. Grade C PF was a severe life-threatening condition leading to abdominal cavity infection, sepsis, and multiple organ failure requiring intensive care, percutaneous puncture catheter, and adequate drainage of peripancreatic fluid. The risk of serious complications occurs. Recently, the field of pancreatic surgery has redefined grade A postoperative PF as a biochemical fistula and no longer as a genuine postoperative PF because of no important clinical significance. Grade B and C PFs indicated the clinical significance of PF. Grouping: Enrolled patients with pancreatic cancer were classified into PF and non-PF groups on the basis of the presence or absence of PF (grades B and C) after LPD.

General data included sex; age; body mass index (BMI; kg/m2); history of smoking, hypertension, and diabetes; and American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification. Preoperative laboratory indicators included values of preoperative hemoglobin (g/L), preoperative platelet count (× 109/L), preoperative neutrophil count (× 109/L), preoperative monocyte count (× 109/L), preoperative lymphocyte count (× 109/L), preoperative albumin (g/L), preoperative total bilirubin (mmol/L), preoperative carbohydrate antigen 199 (CA199) (U/mL), preoperative carbohydrate antigen-CA125 (U/mL), preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL), and preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (ng/mL). Intraoperative and postoperative indices included intraoperative blood loss (mL), operative time (min), pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct diameter (mm), and Am levels in the drainage fluid on the first postoperative day (Am, U/L).

Data were analyzed and processed using SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM Corp.). Quantitative data with a normal distribution are expressed as, and the t-test was used to compare the data between the groups. Normal distribution of the measurement data was not fitted to the median (first quartile, third quartile) or M (P25, P75) using a nonparametric test between the groups. Count data are expressed as (%), and the χ2 test was used to compare the data between the groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used analyze the factors influencing PF after LPD in patients with pancreatic cancer. The receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess the risk factors for pancreatic cancer and the predictive value of LPD for postoperative PF. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Among the 201 patients with pancreatic cancer enrolled in this study, 123 had grade A PF, 14 had grade B PF, and one had grade C PF. Fifteen patients with grades B and C PF, with a probability of 7.46%, were enrolled in the PF group. A total of 186 patients with and without grade A PF were included in the non-PF group.

The proportions of male and hypertension and BMI were higher in the PF group than in the non-PF group (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

| Profile | PF group (n = 15) | Non-PF group (n = 186) | t/χ2/z value | P value |

| Sex | 5.227 | 0.022 | ||

| Male | 13 (86.67) | 105 (56.45) | ||

| Female | 2 (13.33) | 81 (43.55) | ||

| Age (yr) | 66.00 ± 8.64 | 62.35 ± 9.19 | 1.486 | 0.139 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.17 ± 2.96 | 22.58 ± 2.43 | 2.404 | 0.017 |

| Smoking history | 0.408 | 0.523 | ||

| Yes | 3 (20.00) | 26 (13.98) | ||

| No | 12 (80.00) | 160 (86.02) | ||

| Hypertension | 6.209 | 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 10 (66.67) | 64 (34.41) | ||

| No | 5 (33.33) | 122 (65.59) | ||

| Combined diabetes | 0.053 | 0.818 | ||

| Yes | 3 (20.00) | 42 (22.58) | ||

| No | 12 (80.00) | 144 (77.42) | ||

| ASA classification | 0.849 | 0.654 | ||

| Level 1 | 0 | 7 (3.76) | ||

| Level 2 | 15 (100) | 176 (94.62) | ||

| Level 3 | 0 | 3 (1.62) |

The preoperative monocyte count were significantly different between patients in the PF group and those in the non-PF group (P < 0.05). Comparison of other preoperative laboratory parameters showed no significant differences (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

| Laboratory index | PF group (n = 15) | Non-PF group (n = 186) | t/χ2/z value | P value |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 129.93 ± 19.42 | 127.24 ± 16.18 | 0.610 | 0.542 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 229.00 (197.00, 293.00) | 233.00 (194.75, 289.00) | -0.113 | 0.910 |

| NEUT (× 109/L) | 4.70 (2.40, 5.60) | 4.10 (2.90, 5.30) | -0.552 | 0.581 |

| Monocyte count (× 109/L) | 0.50 (0.40, 0.70) | 0.50 (0.40, 0.53) | -2.020 | 0.043 |

| Lymphocyte count (× 109/L) | 1.60 (1.10, 1.70) | 1.50 (1.20, 1.90) | -0.125 | 0.901 |

| ALB (g/L) | 41.57 ± 3.95 | 43.29 ± 4.08 | -1.579 | 0.116 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 14.10 (7.90, 87.20) | 27.50 (11.20, 103.15) | -1.199 | 0.231 |

| Carbohydrate antigen (CA199) | 2.197 | 0.138 | ||

| ≥ 35 U/mL | 14 (93.33) | 143 (76.88) | ||

| < 35 U/mL | 1 (6.67) | 43 (23.12) | ||

| Carbohydrate antigen (CA125, U/mL) | 17.30 (11.50, 24.40) | 15.80 (10.80, 24.20) | -0.198 | 0.843 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 3.38 (2.23, 3.79) | 2.87 (2.16, 3.83) | -0.443 | 0.658 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.28 (2.01, 3.83) | 3.26 (2.03, 5.32) | -1.317 | 0.188 |

The proportions of soft pancreatic texture, diameter of pancreatic duct ≤ 3 mm, and Am > 1069 U/L were greater in the PF group than in the non-PF group (all P < 0.05). Moreover, the operation time was longer in the PF group than in the non-PF group (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Operation-related index | PF group (n = 15) | Non-PF group (n = 186) | t/χ2/z value | P value |

| Pancreatic texture | 64.728 | < 0.001 | ||

| Soft | 11 (93.33) | 11 (5.91) | ||

| Hard | 4 (6.67) | 175 (94.09) | ||

| Pancreatic duct diameter | 7.807 | 0.005 | ||

| > 3 mm | 5 (33.33) | 128 (68.82) | ||

| ≤ 3 mm | 10 (66.67) | 58 (31.18) | ||

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 200.00 (200.00, 300.00) | 200.00 (100.00, 300.00) | -1.939 | 0.052 |

| Operation time (min) | 439.87 ± 51.184 | 382.94 ± 61.74 | 3.474 | 0.001 |

| Am | 17.323 | < 0.001 | ||

| > 1069 U/L | 12 (80.00) | 52 (27.96) | ||

| ≤ 1069 U/L | 3 (20.00) | 134 (72.04) |

Considering the occurrence of PF after LPD for patients with pancreatic cancer as the dependent variable and the related indicators that may affect the occurrence of PF after LPD for pancreatic cancer patients as the independent variables, the eight factors with meaningful differences in Tables 1-3, including sex, BMI, hypertension, preoperative monocyte count, soft pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct diameter, operation time, and Am, were analyzed using a logistic regression model. The variable assignment is shown in Table 4, in which BMI, preoperative monocyte count, and operation time were assigned on the basis of the best cut-off value determined by the corresponding ROC curve drawn using MedCalc software. Logistic regression analysis showed that BMI (> 24.91 kg/m2), hypertension, soft pancreatic texture, and surgery time (> 414 min) were the associated risk factors for postoperative PF in patients with pancreatic cancer after LPD (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| Variable | Variable name | Assignment description |

| Pancreatic fistula in patients with pancreatic cancer after LPD | Y | Yes = 1 |

| No = 0 | ||

| Sex | X1 | Male = 1 |

| Female = 0 | ||

| BMI | X2 | > 24.91 kg/m² = 1 |

| ≤ 24.91 kg/m² = 0 | ||

| Hypertension | X3 | Yes = 1 |

| No = 0 | ||

| Monocyte count | X4 | > 0.4 × 109/L = 1 |

| ≤ 0.4 × 109/L = 0 | ||

| Pancreatic texture | X5 | Soft = 1 |

| Hard = 0 | ||

| Pancreatic duct diameter | X6 | > 3 mm = 1 |

| ≤ 3mm = 0 | ||

| Operation time | X7 | > 414 min = 1 |

| ≤ 414 min = 0 | ||

| Am | > 1069 U/L = 1 | |

| ≤ 1069 U/L = 0 |

| Variable | B value | SE value | Wald value | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Sex | 1.086 | 1.039 | 1.091 | 0.296 | 2.961 | 0.386-22.71 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 2.637 | 1.022 | 6.661 | 0.010 | 13.978 | 1.886-103.581 |

| Hypertension | 2.138 | 0.989 | 4.67 | 0.031 | 8.484 | 1.22-58.994 |

| monocyte count (× 109/L) | 1.591 | 1.135 | 1.966 | 0.161 | 4.909 | 0.531-45.372 |

| Pancreatic texture | 3.738 | 1.019 | 13.448 | < 0.001 | 42.015 | 5.698-309.782 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter | -0.755 | 1.122 | 0.452 | 0.501 | 0.470 | 0.052-4.244 |

| Operation time (min) | 2.735 | 1.146 | 5.694 | 0.017 | 15.41 | 1.63-145.674 |

| Am (U/L) | 1.662 | 1.056 | 2.476 | 0.116 | 5.268 | 0.665-41.734 |

The results analyzed by the ROC curve indicated that the areas under the curve (AUCs) of BMI, hypertension, soft pancreatic texture, and operation time were 0.655, 0.661, 0.873, and 0.758, respectively, which had a certain predictive efficacy (P < 0.05) (Table 6 and Figure 1).

| Factor | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | 95%CI | P value |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 0.655 | 0.467 | 0.844 | 0.496-0.815 | 0.045 |

| Hypertension | 0.661 | 0.667 | 0.656 | 0.518-0.805 | 0.038 |

| Pancreatic texture | 0.837 | 0.733 | 0.941 | 0.702-0.972 | < 0.001 |

| Operation time (min) | 0.758 | 0.800 | 0.715 | 0.634-0.881 | 0.001 |

With the increasing development and maturity of laparoscopic technology, LPD has gradually replaced PD as the first-choice treatment for pancreatic cancer[10]. Compared with PD, LPD has the benefits of less trauma, less bleeding, quicker recovery, shorter hospitalization period, and fewer postoperative complications; however, both PD and LPD have a high postoperative mortality. PF is also a major cause of postoperative death[11]. Therefore, the general data of patients with pancreatic cancer and the perioperative factor index, which is used to assess their risk of postoperative PF after LPD, intervene, and decrease the rate of patients with postoperative PF, have important clinical significance.

Many studies have suggested that an excessive BMI is associated with postoperative PF[12-15]. This study’s findings also confirmed a higher BMI in the PF group than in the non-PF group (P < 0.05). Further logistic regression analysis revealed that a BMI > 24.91 kg/m² was a risk factor for PF after LPD in patients with pancreatic cancer. This may be associated with the high difficulty of surgery in patients with high BMIs; the position of the pancreas in patients with a high BMI is deeper than that in people with a healthy BMI, which makes it difficult to perform pancreatojejunostomy. Concurrently, high visceral fat leads to a softer texture of the pancreas and more abundant adipose tissue under the capsule, which is not conducive for anastomotic suturing and prolongs the healing time[16,17]. Our results also showed that soft pancreatic texture increases the probability of PF risk after LPD. The soft texture of the pancreas has better exocrine function and can secrete more trypsinogen than the normal pancreatic texture[18]. The soft pancreas in matches is easy to tear and suture, causing pancreatic leakage and corrosion of surrounding tissue and blood vessels, inducing and aggravating postoperative PFs[19,20]. However, the hardness of the pancreas can only be subjectively evaluated by observing its morphology under laparoscopy because of the lack of direct contact with the pancreas during LPD; therefore, its texture accuracy needs to be investigated owing to the lack of standardized criteria for assessing the softness and hardness of the pancreas.

This study showed that a long surgery time can lead to an increased risk of PF after LPD for pancreatic cancer treatment. Notably, a long surgery time is related to factors such as instability of the surgical team, limitations of surgical instruments, and failure to overcome the learning curve of LPD (mainly the small number of activities in the early stages of LPD)[21,22]. Gouma et al[23] found that the rate of postoperative complications and mortality in LPD were related to the level of surgeons and the scale of hospitals, whereas the scale of hospitals was mainly related to the number of surgeries performed. The aforementioned conclusions may explain the relationship between the surgery time and postoperative PF. In addition, this study found that comorbid hypertension was significantly associated with the development of PF after LPD. Analysis of its possible causes is that patients with hypertension are generally accompanied by vascular stiffness and hemodynamic weakening, leading to thrombosis, which is not conducive to postoperative anastomosis. This promotes the formation or aggravation of PFs[24,25].

ROC curve analysis showed that BMI, hypertension, soft pancreatic texture, and surgery time were valuable predictors of PF after LPD in patients with pancreatic cancer, with AUCs of 0.655, 0.661, 0.873, and 0.758, respectively. Our study limitations were that we used a small sample size from a single center, only considered clinical factors, and failed to comprehensively analyze patients’ lifestyles and genetic factors. In the future, it is still necessary to study a larger sample size, adopt a multicenter study design, and consider patients’ lifestyles and genetic backgrounds to further analyze factors relating to the development of PF after LPD treatment for pancreatic cancer.

In summary, high BMI, soft pancreatic texture, long surgery time, and hypertension are all risk factors for PF after LPD in patients with pancreatic cancer. For patients with a high BMI (> 24.91 kg/m²), their weights should be controlled by strengthening diet management combined with appropriate exercise measures. Patients with high blood pressure should undergo corresponding antihypertensive therapy preoperatively. If the patient’s pancreas is found to have a soft texture during the operation, the surgeon should be as cautious as possible, manage the anastomosis carefully, and control the operation time by continuously improving surgical skills and teamwork.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Battista S, Italy; Ikeda H, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Karunakaran M, Barreto SG. Surgery for pancreatic cancer: current controversies and challenges. Future Oncol. 2021;17:5135-5162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shen Y, Jin W. Early enteral nutrition after pancreatoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:817-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Russell TB, Aroori S. Procedure-specific morbidity of pancreatoduodenectomy: a systematic review of incidence and risk factors. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92:1347-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Niu CY, Ji B, Dai XL, Guan QC, Liu YH. [Use of alternative pancreatic fistula risk score system for patients with clinical relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula after laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2021;59:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sert OZ, Berkesoglu M, Canbaz H, Olmez A, Tasdelen B, Dirlik MM. The factors of pancreatic fistula development in patients who underwent classical pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Ital Chir. 2021;92:35-40. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ramavath K, Subbiah Nagaraj S, Kumar M, Raypattanaik NM, Dahiya D, Savlania A, Tandup C, Kalra N, Behera A, Kaman L. Visceral Obesity as a Predictor of Postoperative Complications After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cureus. 2023;15:e35815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Martin AN, Narayanan S, Turrentine FE, Bauer TW, Adams RB, Zaydfudim VM. Pancreatic duct size and gland texture are associated with pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy but not after distal pancreatectomy. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tempero MA. NCCN Guidelines Updates: Pancreatic Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CR, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery. 2017;161:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3041] [Cited by in RCA: 2956] [Article Influence: 369.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 10. | Yin TY, Zhang H, Wang M, Qin RY. [The value and controversy of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in the treatment of pancreatic cancer]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2022;60:894-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kawaida H, Kono H, Hosomura N, Amemiya H, Itakura J, Fujii H, Ichikawa D. Surgical techniques and postoperative management to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3722-3737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 12. | Costa Santos M, Cunha C, Velho S, Ferreira AO, Costa F, Ferreira R, Loureiro R, Santos AA, Maio R, Cravo M. Preoperative biliary drainage in patients performing pancreaticoduodenectomy : guidelines and real-life practice. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2019;82:389-395. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Utsumi M, Aoki H, Nagahisa S, Nishimura S, Une Y, Kimura Y, Watanabe M, Taniguchi F, Arata T, Katsuda K, Tanakaya K. Preoperative predictive factors of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: usefulness of the CONUT score. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2020;99:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nong K, Zhang Y, Liu S, Yang Y, Sun D, Chen X. Analysis of pancreatic fistula risk in patients with laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy: what matters. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520943422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kiełbowski K, Bakinowska E, Uciński R. Preoperative and intraoperative risk factors of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy - systematic review and meta-analysis. Pol Przegl Chir. 2021;93:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | He C, Zhang Y, Li L, Zhao M, Wang C, Tang Y. Risk factor analysis and prediction of postoperative clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. BMC Surg. 2023;23:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zarzavadjian Le Bian A, Fuks D, Montali F, Cesaretti M, Costi R, Wind P, Smadja C, Gayet B. Predicting the Severity of Pancreatic Fistula after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Overweight and Blood Loss as Independent Risk Factors: Retrospective Analysis of 277 Patients. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2019;20:486-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schuh F, Mihaljevic AL, Probst P, Trudeau MT, Müller PC, Marchegiani G, Besselink MG, Uzunoglu F, Izbicki JR, Falconi M, Castillo CF, Adham M, Z'graggen K, Friess H, Werner J, Weitz J, Strobel O, Hackert T, Radenkovic D, Kelemen D, Wolfgang C, Miao YI, Shrikhande SV, Lillemoe KD, Dervenis C, Bassi C, Neoptolemos JP, Diener MK, Vollmer CM Jr, Büchler MW. A Simple Classification of Pancreatic Duct Size and Texture Predicts Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula: A classification of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery. Ann Surg. 2023;277:e597-e608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen CB, McCall NS, Pucci MJ, Leiby B, Dabbish N, Winter JM, Yeo CJ, Lavu H. The Combination of Pancreas Texture and Postoperative Serum Amylase in Predicting Pancreatic Fistula Risk. Am Surg. 2018;84:889-896. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Imam A, Khalayleh H, Brakha M, Benson AA, Lev-Cohain N, Zamir G, Khalaileh A. The effect of atrophied pancreas as shown in the preoperative imaging on the leakage rate after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2022;26:184-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Azzi AJ, Shah K, Seely A, Villeneuve JP, Sundaresan SR, Shamji FM, Maziak DE, Gilbert S. Surgical team turnover and operative time: An evaluation of operating room efficiency during pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1391-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rothstein DH, Raval MV. Operating room efficiency. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2018;27:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, Obertop H. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang JY, Huang J, Zhao SY, Liu X, Xiong ZC, Yang ZY. Risk Factors and a New Prediction Model for Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1897-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ke Z, Cui J, Hu N, Yang Z, Chen H, Hu J, Wang C, Wu H, Nie X, Xiong J. Risk factors for postoperative pancreatic fistula: Analysis of 170 consecutive cases of pancreaticoduodenectomy based on the updated ISGPS classification and grading system. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |