Published online Apr 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i4.1189

Peer-review started: November 26, 2023

First decision: December 11, 2023

Revised: January 11, 2024

Accepted: March 18, 2024

Article in press: March 18, 2024

Published online: April 27, 2024

Processing time: 148 Days and 1.3 Hours

With less than 90 reported cases to date, stercoral perforation of the colon is a rare occurrence. Stercoral ulceration is thought to occur due to ischemic pressure necrosis of the bowel wall, which is caused by the presence of a stercoraceous mass. To underscore this urgent surgical situation concerning clinical presen

A 66-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gout pre

In stercoral perforations, a diagnosis should be diligently pursued, especially in older adults, and prompt surgical intervention should be implemented.

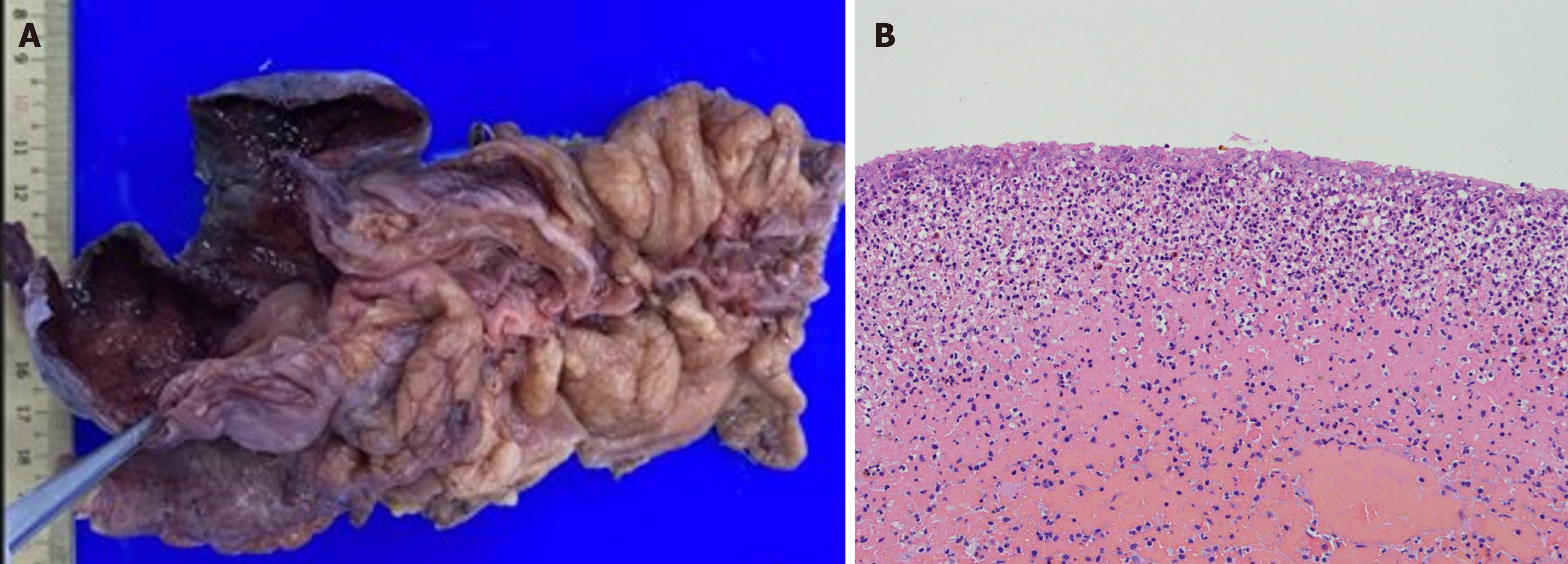

Core Tip: Spontaneous perforations are classified as either stercoral or idiopathic based on underlying etiologic and pathologic factors. In this case, the operative findings and histopathology report led us to conclude that the perforation was stercoral. This perforation is characterized by a rounded or ovoid-shaped defect with underlying necrotic and inflammatory edges in the absence of significant injuries, obstructions, tumors, and diverticulosis. This condition is commonly observed in chronically ill patients at a rate of 47% in the sigmoid colon and 30% in the rectosigmoid colon. In this manuscript, we present a rare case of bezoar-induced stercoral perforation of the cecum.

- Citation: Yu HC, Pu TW, Kang JC, Chen CY, Hu JM, Su RY. Stercoral perforation of the cecum: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(4): 1189-1194

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i4/1189.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i4.1189

With less than 90 reported cases to date, stercoral perforation of the colon is a rare occurrence. Stercoral ulceration is thought to occur due to ischemic pressure necrosis of the bowel wall, which is caused by the presence of a stercoraceous mass[1]. To underscore this urgent surgical situation concerning clinical presentation, surgical treatment, and results, we present the case of a 66-year-old man with a stercoral perforation.

A 66-year-old man presented at the emergency department with a 4-h history of lower abdominal and epigastric pain with low-grade fever.

The patient had a normal bowel movement at around 6 am on the day of presentation, then 4 h later he developed abdominal pain in the lower abdomen that increased in intensity and extended to the epigastric area. The pain was accompanied by multiple bowel movements, without nausea or vomiting. He presented to the hospital four hours after the abdominal pain started with lower abdominal pain.

The patient had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gout, and regularly visited the cardiology outpatient department for follow-up and maintenance medication. The patient had no history of rectal bleeding, anorexia, or weight loss. Seven years before presentation, the patient underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed no abnormal mucosal or mass lesions up to the ileocecal valve.

The patient has a history of cigarette smoking, averaging 1-1.5 packs per day for decades. Additionally, he occasionally consumed alcohol socially. Regarding family history, his mother had a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

On physical examination, the patient was conscious and alert. His vital signs were: Body temperature, 36.2 degree Celcius; pulse, 96 beats per minute; blood pressure, 142/82 mmHg. Examination of the abdomen demonstrated rebound tenderness in the right lower quadrants and suprapubic area upon palpation, normal bowel sounds, no tympanic sounds, and no Murphy’s sign. A digital rectal examination revealed traces of stool with a minimal amount of gross blood. No masses were palpable.

A complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 18.05 × 109/L and a haemoglobin level of 14.7 gm/dL. Other laboratory investigations showed normal results.

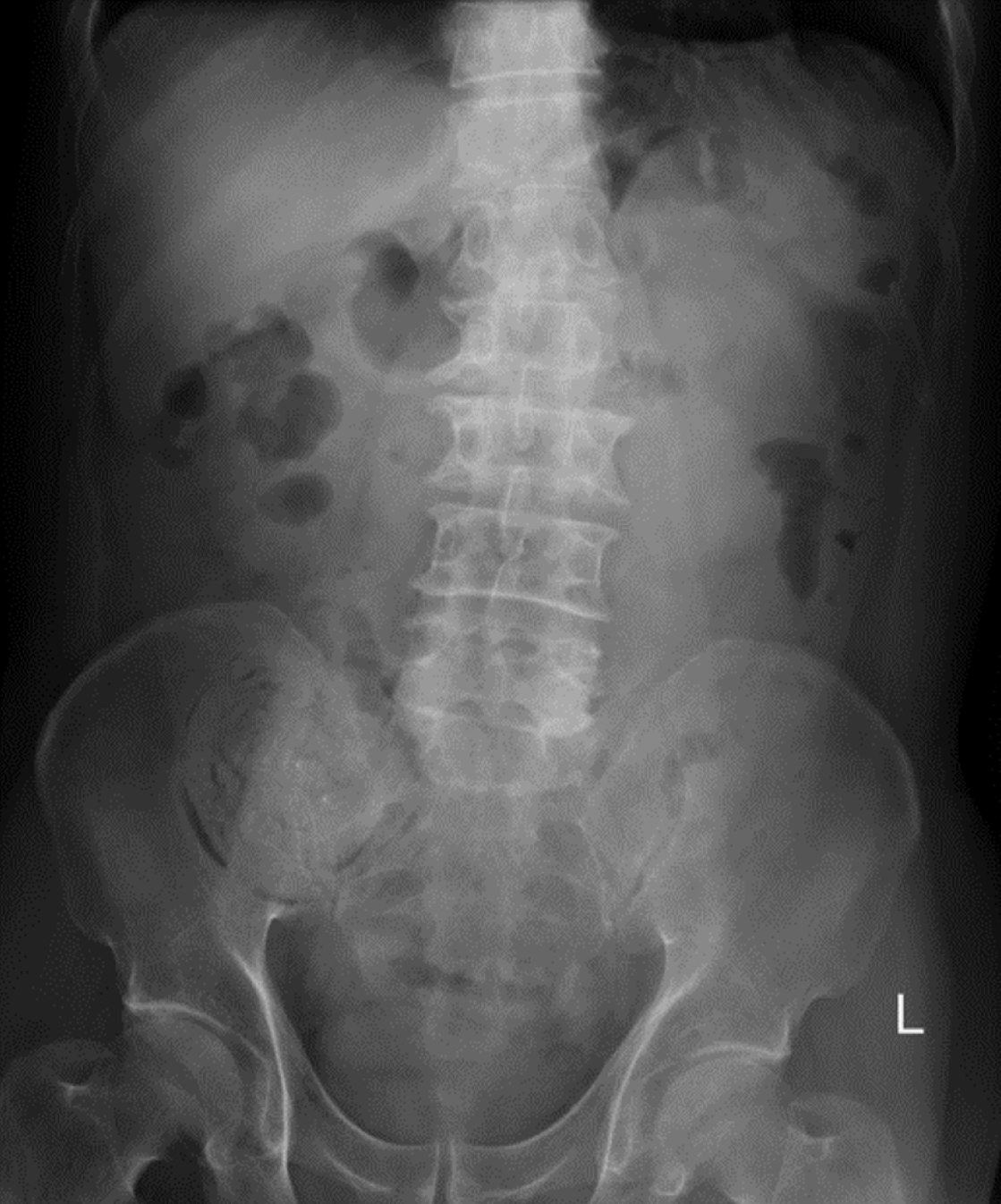

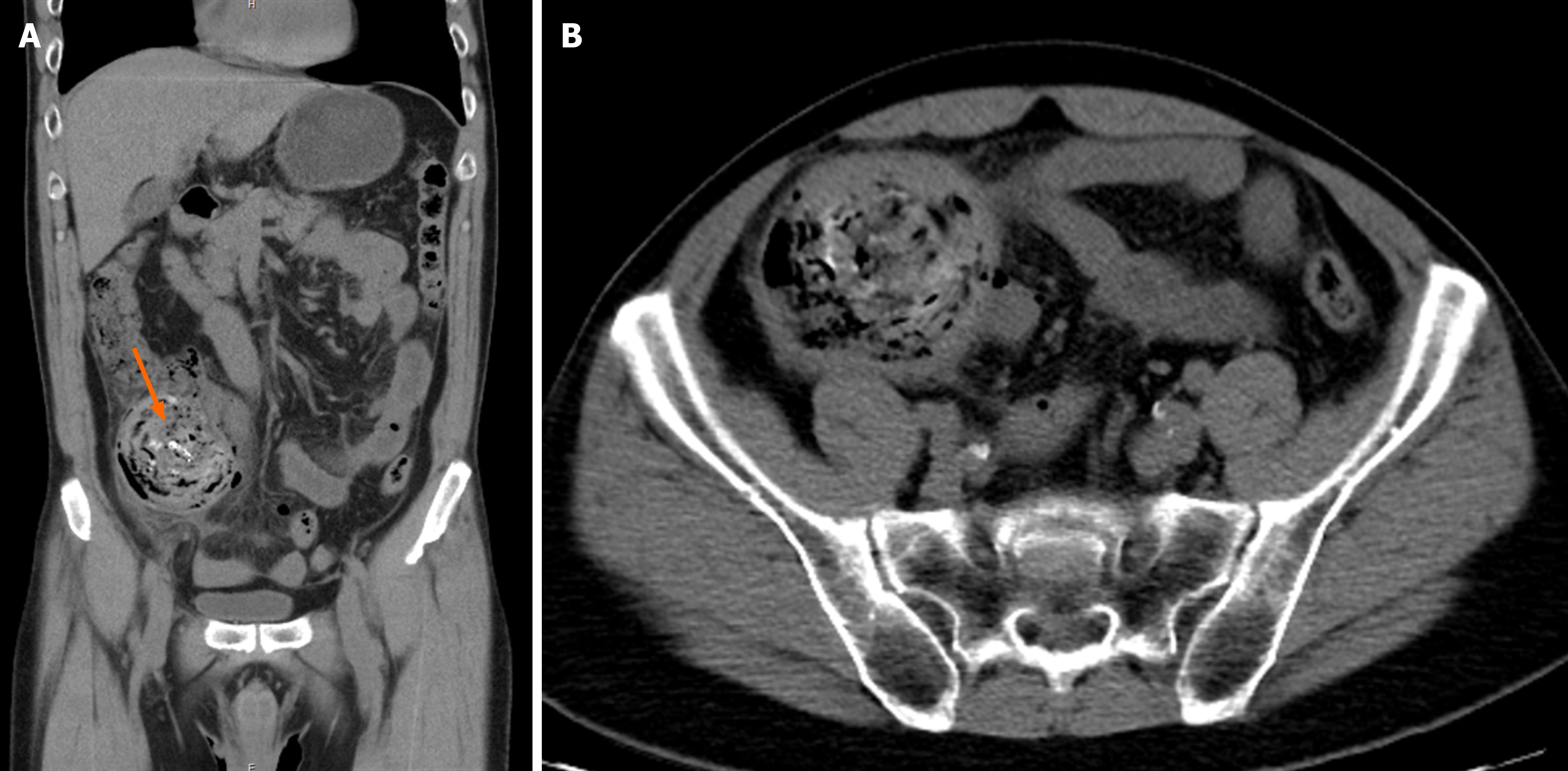

A plain radiograph of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder revealed a focal lesion in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen (Figure 1). Further imaging via an abdominal computed tomography scan showed a suspected bezoar (approximately 7.6 cm in diameter) in the dilated cecum accompanied by pericolic fat stranding, mild proximal dilatation of the ileum, pneumoperitoneum, and minimal ascites (Figure 2A and B).

Spontaneous cecal perforation, status post right hemicolectomy on admission to the hospital, status post wound debridement with rectus abdominis flap on post-operative day 12.

The intravenous antibiotics flomoxef and metronidazole, were administered. A decision was made to perform explo

Postoperatively, the patient recovered from brief atelectasis. However, the wound did not respond well to local treatment with an aqua beta-iodine dressing. Fascial dehiscence occurred with bowel exposure. Therefore, wound debridement was performed using a rectus abdominis flap on post-operative day 12. After the operation, oral feeding was gradually advanced, and the patient tolerated it well. Subsequently, he was discharged in stable condition and followed up in our outpatient clinic.

Spontaneous cecal perforation is the sudden perforation of a previously clinically healthy colon in the absence of an underlying disease or injury. To date, fewer than 100 cases have been reported in the literature[2]. In spontaneous perforations, the mean age of affected patients is 65 years. Furthermore, men are more susceptible to perforation, with a ratio of 2:1 in older adult men and women, respectively[3]. Mortality rates associated with cecal perforation are high, ranging from 30% to 72%[4]. The prognosis of spontaneous cecal perforation is influenced by various factors, such as the timing of perforation, the extent of peritoneal contamination, and the timeliness of intervention.

In 1894, Berry classified spontaneous perforations as either stercoral or idiopathic. This classification is based on underlying etiological and pathological factors[5]. Maurer et al[6] established guidelines for identifying stercoral per

A bezoar is a firm, solid, enduring foreign object found in the gastrointestinal tract. They can be found in various parts of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus and colon. Four distinct types of bezoars have been identified based on their originating material: Phytobezoars, trichobezoars, concretions, and pharmacobezoars[9]. None of these described causes seemed to match this patient’s condition. In a retrospective analysis study, alcohol consumption, hypertension, and diabetes were reported to serve as risk factors for bezoars[10]. Therefore, further investigation may be necessary to identify the specific reason of bezoar formation in this case.

Idiopathic perforation occurs because of the asymmetrical distribution of intraluminal pressure at the pelvic-rectal angle in the absence of obviously impacted stool or any identifiable cause of perforation[11]. The exact cause of spon

Cecal perforation occurring spontaneously is an uncommon occurrence linked with heightened morbidity and mortality rates. Irrespective of the surgical approach, detecting it early and swiftly resorting to surgical intervention are key tactics linked with better results. Hence, it’s imperative to strive for a timely diagnosis, particularly in the elderly, and promptly initiate surgical measures.

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the people at the Department of Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital Songsang Branch. This report would not have been possible without their efforts in data collection and interprofessional collaboration in treating this patient.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghannam WM, Egypt S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Patel VG, Kalakuntla V, Fortson JK, Weaver WL, Joel MD, Hammami A. Stercoral perforation of the sigmoid colon: report of a rare case and its possible association with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am Surg. 2002;68:62-64. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Makki AM, Hejazi S, Zaidi NH, Johari A, Altaf A. Spontaneous Perforation of Colon: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Case Rep Clin Med. 2014;3:392-397. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Galanis I, Dragoumis D, Kalogirou T, Lakis S, Kotakidou R, Atmatzidis K. Spontaneous perforation of solitary ulcer of transverse colon. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:138-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Laskin MD, Tessler K, Kives S. Cecal perforation due to paralytic ileus following primary caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Al Shukry S. Spontaneous perforation of the colon clinical review of five episodes in four patients. Oman Med J. 2009;24:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maurer CA, Renzulli P, Mazzucchelli L, Egger B, Seiler CA, Büchler MW. Use of accurate diagnostic criteria may increase incidence of stercoral perforation of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:991-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dubinsky I. Stercoral perforation of the colon: case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:323-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Erdemir A, Ağalar F, Çakmakçı M, Ramadan S, Baloğlu H. A rare cause of mechanical intestinal obstruction: Pharmacobezoar. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2015;31:92-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu LN, Wang L, Jia SJ, Wang P. Clinical Features, Risk Factors, and Endoscopic Treatment of Bezoars: A Retrospective Analysis from a Single Center in Northern China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e926539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kurane SB, Kurane BT. Idiopathic colonic perforation in adult-a rare case. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:63-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Parish KL, Chapman WC, Williams LF Jr. Ischemic colitis. An ever-changing spectrum? Am Surg. 1991;57:118-121. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ervens J, Schiffmann L, Berger G, Hoffmeister B. Colon perforation with acute peritonitis after taking clindamycin and diclofenac following wisdom tooth removal. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:330-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |