Published online Apr 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i4.1043

Peer-review started: October 26, 2023

First decision: December 7, 2023

Revised: January 2, 2024

Accepted: January 29, 2024

Article in press: January 29, 2024

Published online: April 27, 2024

Processing time: 179 Days and 5.5 Hours

The study aimed to analyze the characteristic clinical manifestations of patients with intestinal disease Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) complicated by digestive tract hemorrhage. Moreover, we aimed to evaluate the value of double-balloon ente

To evaluate the value of DBE in the diagnosis and the prognosis after laparoscopic diverticula resection for MD with bleeding.

The study retrospectively analyzed relevant data from 84 MD patients treated between January 2015 and March 2022 and recorded their clinical manifestations, auxiliary examination, and follow-up after laparoscopic resection of diverticula.

(1) Among 84 MD patients complicated with hemorrhage, 77 were male, and 7 were female with an average age of 31.31 ± 10.75 years. The incidence was higher in men than in women of different ages; (2) Among the 84 MD patients, 65 (78.40%) had defecated dark red stools, and 50 (58.80%) had no accompanying symptoms during bleeding, indicating that most MD bleeding appeared a dark red stool without accompanying symptoms; (3) The shock index of 71 patients (85.20%) was < 1, suggesting that the blood loss of most MD patients was less than 20%–30%, and only a few patients had a blood loss of > 30%; (4) The DBE-positive rate was 100% (54/54), 99mTc-pertechnetate-positive scanning rate was 78% (35/45) compared with capsule endoscopy (36%) and small intestine computed tomography (19%). These results suggest that DBE and 99mTc-pertechnetate scans had significant advantages in diagnosing MD and bleeding, especially DBE was a highly precise examination method in MD diag

Bleeding associated with MD was predominantly observed in male adolescents, particularly at a young age. DBE was a highly precise examination method in MD diagnosis. Laparoscopic diverticula resection effectively preven

Core Tip: Our study aimed to analyze the characteristic clinical manifestations of patients with intestinal disease Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) complicated by digestive tract hemorrhage. Our study found that MD tends to occur in young men, and double-balloon enteroscopy has a high diagnostic value for MD. The main endoscopic manifestation of MD accompanied by bleeding was ulcer, and gastric/pancreatic mucosal ectopia was the main pathological factor causing ulcer.

- Citation: He T, Yang C, Wang J, Zhong JS, Li AH, Yin YJ, Luo LL, Rao CM, Mao NF, Guo Q, Zuo Z, Zhang W, Wan P. Single-center retrospective study of the diagnostic value of double-balloon enteroscopy in Meckel’s diverticulum with bleeding. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(4): 1043-1054

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i4/1043.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i4.1043

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD), a common congenital true diverticulum, is a distal ileal diverticulum formed by incomplete vitelline duct degeneration during embryonic development[1]. This congenital intestinal malformation was first des

We collect the information of patients who, due to gastrointestinal bleeding, underwent gastroscopy and colonoscopy. We did not find bleeding lesions, but the patients were considered to have small intestinal bleeding and were admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology of the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province between January 2015 and March 2022. Based on the diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal bleeding[5], personally selected examinations, including examination of 99mTc-pertechnetate, small intestine computed tomography (CT), capsule endoscopy (CE), and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), 84 patients were eventually diagnosed with MD. This study was organized by the First People’s Hospital, affiliated with the Kunming University of Science and Technology Ethics Committee in Yunnan Province. All patients or their legal representatives provided informed consent, and all personal information before analysis was confidential.

The clinical data of 84 patients diagnosed with MD and hemorrhage by DBE and other auxiliary examinations (small intestine CT, nuclide scan, and CE) in the past 7 years were retrospectively analyzed. Clinical data included sex, age, bleeding characteristics, blood routine, biochemical indicators, coagulation function test, imaging or endoscopy, post

A DBE system was used, either an EN-450P5 diagnostic endoscope or a 450T5 therapeutic endoscope (Fujinonsee Inc. Japan Saitama).

The day before the DBE examination, the patient began eating a low-fat, ash-free diet and avoided colored food. After oral examination, the patient fasted from solid food for 12 h and liquid food for 6 h. After anal examination, 2000 mL of diluted polyethylene glycol electrolyte powder (69.56 mg × 2) was be taken 5–6 h before the examination and operation, with an administration duration not exceeding 2 h. Patients who could not tolerate large liquid volumes were told to do it in stages, with 1000 mL given the night before the exam, and the other 1000 mL given 4–6 h before the exam. Deep sedation was performed under endotracheal intubation in patients undergoing oral examination, while patients un

All DBEs were performed by two experienced endoscopists in the Digestive Endoscopy Center of our hospital. The oral or anal examination route was selected by combining the bleeding characteristics and preoperative examination results. The examination was done in close coordination with a doctor and a nurse. Before the operation, water was poured into the space between the endoscope and the external cannula to reduce friction. During the examination, the technique of Yamamoto et al[6] was performed which involves the systematic manipulation of the small intestine onto the endoscopic body using the “push and pull” action. Additionally, we employed the fixed effect of an airbag inflating and deflating to stabilize the small intestine, facilitating the insertion of the colonoscope into the small intestine cavity to achieve maximum depth. The examination was completed when the target lesion was detected or when the endoscope physician decided that no further endoscopy was necessary according to the situation. If no lesion was detected, either through submucosal injection of methylene blue or using a release clamp device marker, the endoscopy proceeded in the other direction on the same day or was rescheduled for a later date. In cases with MD detection, the distance between the diverticulum and the ileocecal valve was recorded by the distance accumulation method.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 software. The count data were expressed as frequency and component ratio (%), and the ratio was compared by chi-square test or F-exact test. Measurement data were tested for normality, and the variance of measured data was tested for normality and homogeneity. Normally distributed data were reported as means ± standard deviation and between-group differences were compared by Student’s t-tests. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The results revealed 84 MD patients complicated with hemorrhage; 19 cases (21.60%) defecated black stool, and 65 (78.40%) defecated dark red stool. In the course of bleeding, 50 cases (58.80%) had no concomitant symptoms, 21 cases (27.10%) had abdominal pain, 11 cases (11.80%) had shock manifestations such as coldness and syncope, and 2 cases (2.40%) had abdominal pain and shock manifestations. This suggests that MD bleeding was significantly (P < 0.01) manifested in dark red blood stool and that most patients had no other concomitant symptoms. The shock index was evaluated by the ratio of heart rate to systolic blood pressure after bleeding[7,8]; the shock index of 71 patients (85.20%) was less than 112 patients (13.60%) fluctuated between 1.0 and 1.5, and only 1 patient (1.10%) had a shock index greater than 1.5. This indicates that the blood loss of most MD patients was less than 20%–30%, and that only a few patients had a blood loss of greater than 30% (P < 0.01). The blood biochemistry results revealed that patients with MD bleeding had secondary hemoglobin decline (75 cases, 89.80%), hypoalbuminemia (42 cases, 47.80%), and coagulation dysfunction (23 cases, 25.00%), but most patients had secondary hypohemoglobinemia and no secondary coagulation dysfunction, with a significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.01; Table 1).

| Clinical analysis | Cases, n | Percentage | χ2 | P value | |

| Sex | Male | 77 | 92.0% | 124.45 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 7 | 8.0% | |||

| Features of gastrointestinal bleeding | Black stool | 19 | 21.6% | 56.82 | < 0.01 |

| Dark red bloody stool | 65 | 78.4% | |||

| Characteristics of disease course | First bleeding | 55 | 65.9% | 17.82 | < 0.01 |

| Recurrent bleeding | 29 | 34.1% | |||

| Concomitant symptoms | Nothing | 50 | 58.8% | 82.31 | < 0.01 |

| Abdominal pain | 21 | 27.1% | |||

| Shock | 11 | 11.8% | |||

| Abdominal pain and shock | 2 | 2.4% | |||

| Shock index | < 1.0 | 71 | 85.2% | 163.06 | < 0.01 |

| 1.0 < index < 1.5 | 12 | 13.6% | |||

| > 1.5 | 1 | 1.1% | |||

| Anemia | Nothing | 9 | 10.2% | 111.36 | < 0.01 |

| Exist | 75 | 89.8% | |||

| Albumin | Normal | 46 | 52.2% | 0.36 | > 0.05 |

| Reduce | 42 | 47.8% | |||

| Abnormal coagulation function | Nothing | 66 | 75.0% | 42.03 | < 0.01 |

| Exist | 23 | 25.0% | |||

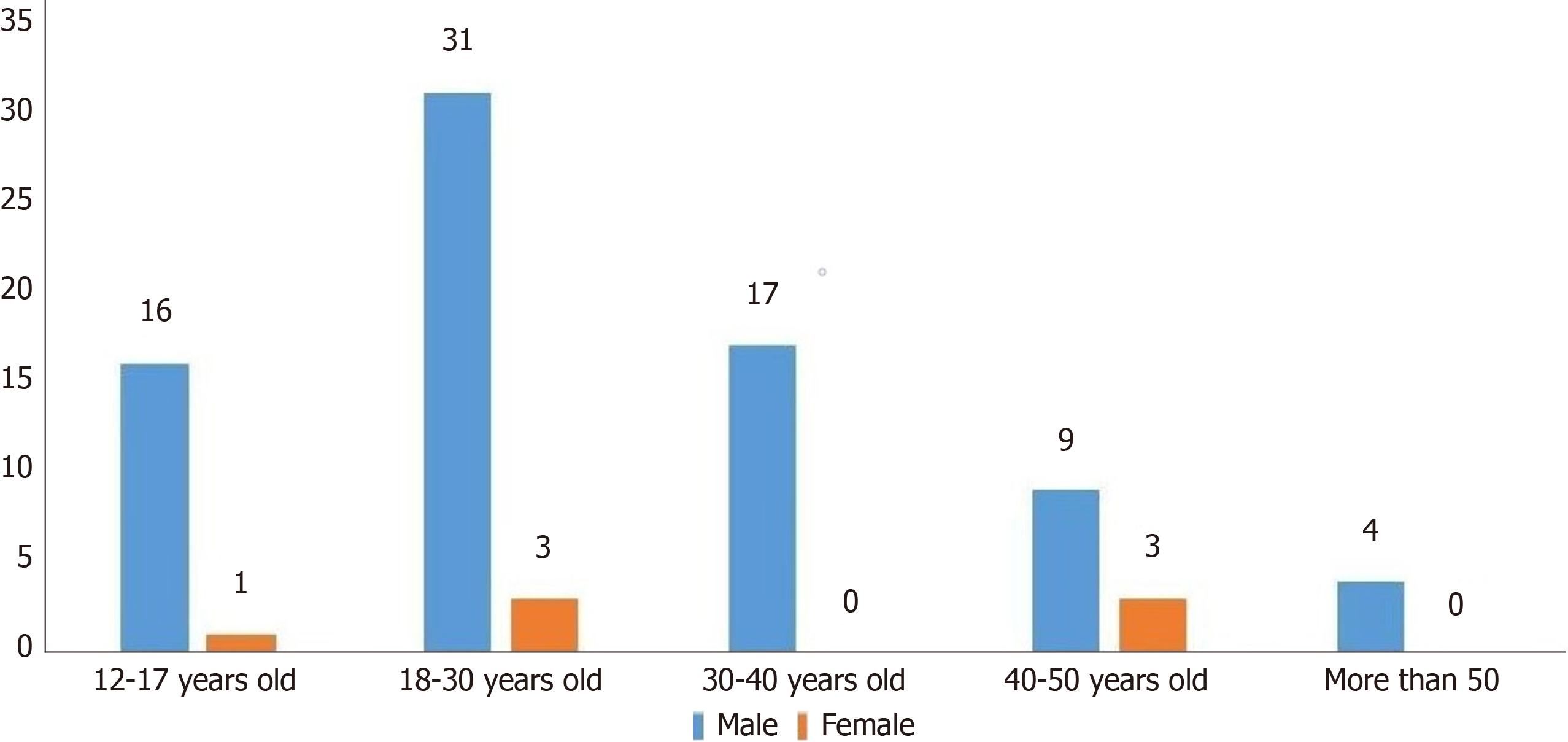

The study included 84 MD patients complicated by bleeding, 77 men and 7 women. The minimum age was 12 years, and the maximum age was 57 years. Among them, 17 patients were younger than 18 years of age, with an average age of 14.35 ± 2.18 years. The average age of 67 adults was 31.31 ± 10.75 years. In different age periods, the incidence of MD he

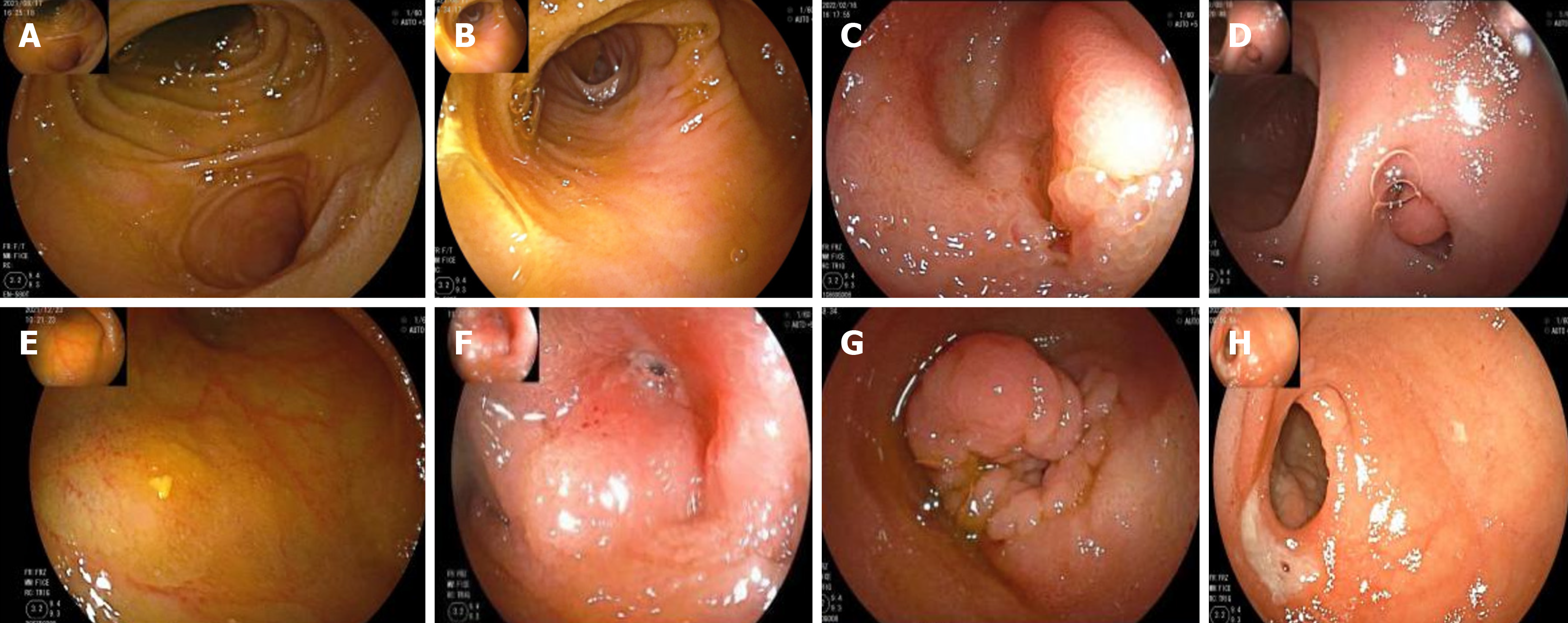

Of the 54 patients who completed the DBE examination, a diverticulum was found in 51 by anal examination. No diverticulum was found in 3 patients by anal examination, and a diverticulum was found by oral examination, which was an inverted diverticulum. The MD location was recorded by the distance accumulation method[9]. The shortest distance to the ileocecal valve was 12 cm, the longest was 140 cm, and the average distance was 63.64 cm ± 30.05 cm. By en

| Manifestation | Cases, n | Percentage | χ2 | P value |

| Normal | 7 | 12.96% | 51.02 | < 0.01 |

| Inflammation | 9 | 16.67% | ||

| Ulcer | 29 | 53.70% | ||

| Varus | 2 | 3.70% | ||

| Hyperplasia | 7 | 12.96% | ||

| Total | 54 | 100.00% | N/A | N/A |

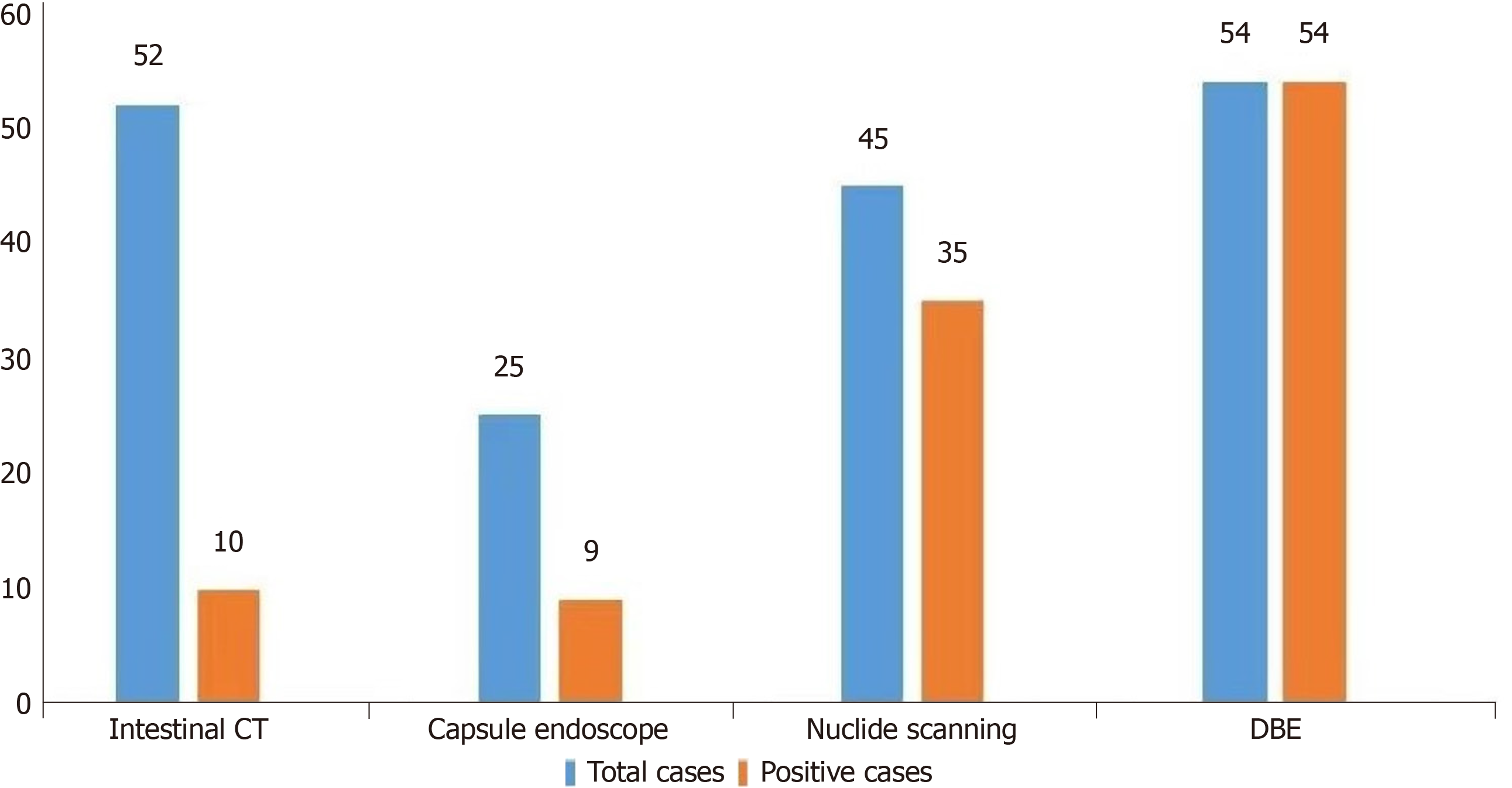

Of the 84 MD patients complicated by hemorrhage, 52 completed CT examination of the small intestine, of whom 10 (19%) were positive. Twenty-five patients completed CE, and 9 (36%) were positive. Forty-five patients underwent 99mTc-pertechnetate scanning, and 35 (78%) were positive. Fifty-four completed DBE, and 54 (100%) were positive (Figure 3).

The positive rate of MD bleeding diagnosed by DBE was significantly higher than that by 99mTc-pertechnetate scan, small intestine CT, and CE. The positivity rate of the 99mTc-pertechnetate scans was higher than that of small intestine CT and CE, suggesting that DBE and 99mTc-sertechnetate scans had significant advantages in diagnosing MD and bleeding, among which DBE had the highest accuracy in MD diagnosis (Table 4).

Herein, 76 patients underwent laparoscopic diverticula resection, and 8 refused surgery and were followed up. Of 55 patients with first gastrointestinal hemorrhage, 50 were treated with laparoscopic diverticula resection. Of 29 cases of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding, 26 underwent laparoscopic diverticula resection.

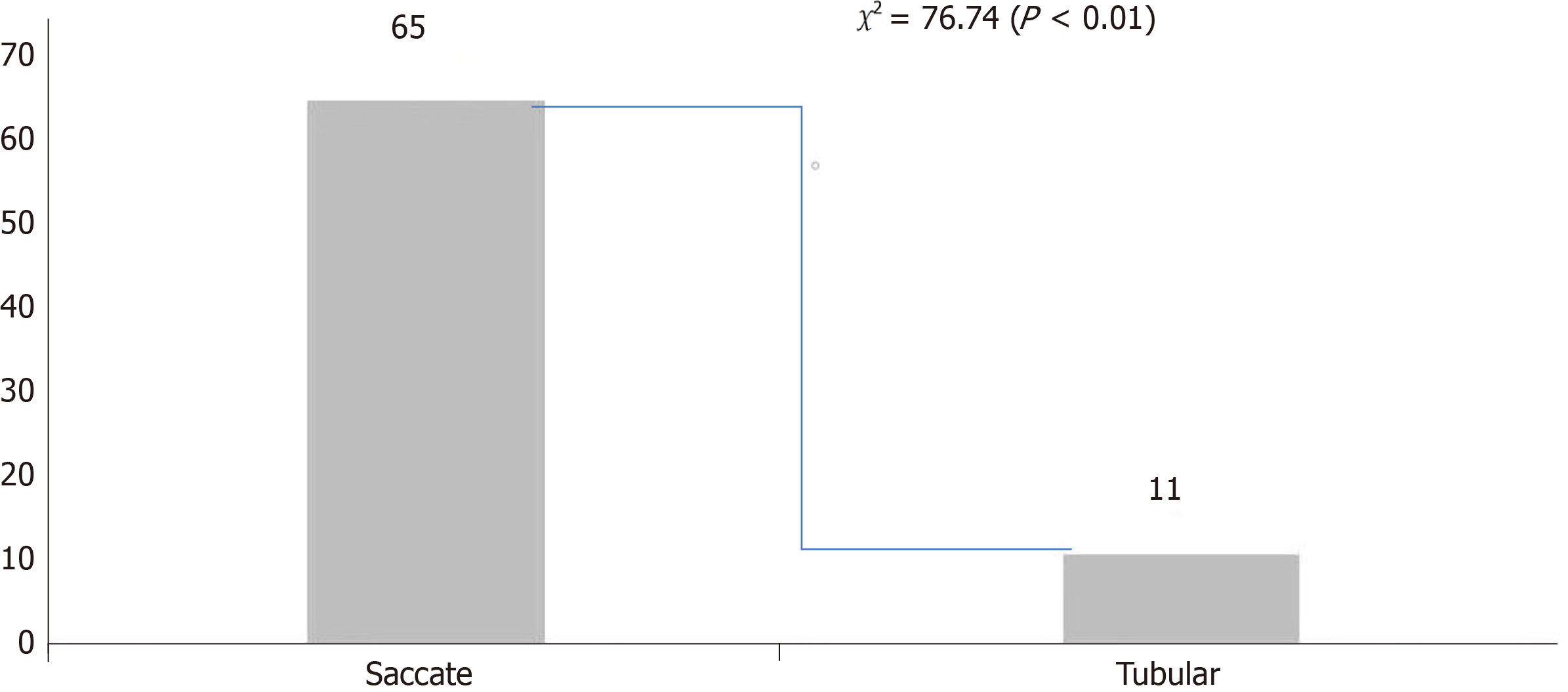

Laparoscopic observation of 76 cases of diverticulum shape presented a clear base and basal organization resembling the normal bowel; MD is the simple type[10]. The shortest length of the diverticulum was 2 cm, the longest was 10 cm, the average was 4.91 cm ± 1.53 cm, the minimum width was 1 cm, the maximum width was 4 cm, and the average was 2.41 cm ± 0.87 cm. Analysis of length and width[11] indicated that when the long diameter was significantly greater than the wide diameter, the aspect ratio was equal to or larger than 3:1. In such circumstances, 11 cases were identified as tubular. Conversely, when the aspect ratio was less than 3:1, 65 cases were classified as saccate. This suggests that MDs with a wide base were more likely to be complicated by bleeding (Figure 4).

Simultaneously, three types of pathological tissues were found in 76 cases of MD, inflammatory cell infiltration in the small intestine in 39 cases (51.3%), ectopic tissue in gastric mucosa in 35 cases (46.1%), and ectopic tissue in the pancreas in 2 cases (2.6%). Preoperative DBE diagnosis was completed in 50 patients undergoing surgery; the pathogenesis of the diverticulum with bleeding was analyzed by combining the mucosal manifestations and histopathology under the endoscope. Of the 17 patients with normal mucosa, inflammatory changes, and varus diverticulum by endoscopy, 3 cases of gastric mucosa/pancreas ectopic location were found, while among the 33 patients with ulcer/hyperplasia under endoscopy, 17 cases of gastric mucosa/pancreas ectopic location were found. There was significant significance between these two groups, suggesting that the formation of endoscopic ulcers and mucosal layer hyperplasia were correlated with the ectopic location of gastric mucosa/pancreas tissue (Table 5).

Laparoscopic resection of the diverticulum after follow-up of 76 patients with MD revealed no bleeding. No surgical treatment of the 8 patients in the follow-up revealed 3 cases of gastrointestinal bleeding recurrence. Compared with the follow-up group, laparoscopic surgery effectively avoided recurrent bleeding in MD patients, indicating that surgical resection of MD patients with bleeding had a better prognosis (Table 6).

The management of patients with small intestinal bleeding poses a difficulty due to the particularity of small intestine anatomical location, limitations of small intestine examination method and uneven levels of small intestinal endoscopy diagnosis and treatment variables However, in 5–10% of gastrointestinal bleeding cases, upper gastrointestinal endo

Most included MD patients were male. The minimum age was 12 years, and the maximum age was 57 years. In any age group, the incidence in male patients was predominant (Figure 1). This indicates that the sex ratio of MD patients with hemorrhage did not change with age. This result is consistent with Hansen’s systematic review[13]. The male-to-female (M:F 1.5–4.0:1.0) sex distribution was reported to be up to 4 times more frequent in men. Çelebi et al[3] reported possible reasons for the high incidence in men. Our study also showed that gastric mucosa/pancreatic mucosa was the main pathological factor causing mucous ulcer in Mekel’s diverticulum, which further explained the possible cause of the high incidence in male patients. The incidence of MD hemorrhage in the group under 30 years of age was higher than in other age groups (Table 2). The age of onset shifted from before 40 to earlier, consistent with other studies[4]. Advance

While the clinical manifestations of MD are varied, a comprehensive understanding of the distinctive bleeding patterns associated with MD can greatly assist clinicians in developing immediate and accurate diagnosis and treatment strategies. Consequently, the clinical characteristic analysis of the 84 cases of MD hemorrhage showed that MD bleeding was significantly manifested by dark red bloody stool (78.40%), with no accompanying symptoms during the bleeding, and a few of cases were secondary to shock (Table 1). After hemorrhage, the shock index (heart rate/systolic blood pressure ratio)[8] evaluation suggested that most MD patients had a bleeding volume of less than 20%–30%, and only a few had a bleeding volume of greater than 30%. Combined with the blood biochemical indicators, most patients with MD bleeding may have had secondary mild hemoglobin decline and no coagulation function disorder. Therefore, most patients with MD bleeding were qualified to complete preoperative DBE examination (Table 1).

Preoperative routine inspection of MD bleeding includes imaging examination (e.g., small bowel CT, small intestine MRI scanning, and high 99mTc-technetium acid salt) and intestinal endoscopy. Small intestinal endoscopies are CE and auxiliary BAE, especially balloon enteroscopy. The auxiliary type is an important test for diagnosing intestinal diseases, but the diagnostic value of MD hemorrhage is rarely reported; therefore, the BAE used in our study was DBE. Herein, of the 54 patients who underwent DBE examination prior to surgery, diverticulum was detected in 51 by anal examination and the remaining 3 were diagnosed with inverted diverticulum through oral examination. The distance between the diverticulum and the ileocecal valve was measured by the distance accumulation method. The results indicate that the shortest recorded distance to the ileocecal valve was 12 cm, the longest was 140 cm, and the average was 63.64 cm ± 30.05 cm. These findings suggest that most MD cases are located in the distal ileum. The transanal examination was more beneficial in detecting MD. However, if no bleeding lesions were found in the transanal route, the possibility of an inverted diverticulum should be examined through an oral approach. The DBE examination of 54 patients was characterized by a “double-chamber sign”. The intestinal mucosa in the diverticulum showed diversification, and the most common diverticulum presented ulcerative changes in the blind end, the inside of the diverticulum, the diverticulum crest (53.70%). Furthermore, 87.04% of cases had significant recent active bleeding following the DBE examination. Notably, the diverticulum mucosa ulceration emerged as the primary cause of MD bleeding (Figure 2, Table 3).

The combined characteristics of patients with pathological histology revealed three types of pathological tissues in 76 cases of MD complicated by bleeding, inflammatory cell infiltration in the small intestine in 52.6%, ectopia of gastric mucosa tissue in 44.9%, and ectopic in pancreas tissue in 2.5%. Preoperative DBE was performed in 51 patients combined with mucosal signs of the diverticulum observed by endoscopy with postoperative histopathology investigation, which identified the underlying etiology. Meanwhile, in the 50 patients who received DBE before surgery, there were 3 cases of ectopic gastric mucosa/pancreas in 17 patients with normal mucosal manifestations, inflammatory changes, and varus diverticulum under endoscopy and 17 cases of ectopic gastric mucosa/pancreas in 33 patients with endoscopic ulcer/hyperplasia group. Differences of the data in the two groups were statistically significant. It is suggested that ulcer for

Based on the diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal bleeding specification combined with the clinical characteristics, individual choice small bowel CT scanning, high 99mTc-technetium acid salt, CE, and BAE examination. Each of these examinations has its advantages in evaluating the condition, with BAE being particularly beneficial in diagnosing patients with MD and bleeding. The accurate results obtained from BAE can provide a solid foundation for establishing an appropriate diagnosis and treatment plan for patients with MD-related hemorrhage.

A total of 52 cases were examined by small bowel CT. The diagnosis of MD bleeding was found to have a rate of 19%. Additionally, 25 cases underwent a complete CE examination, revealing a rate of 36%. Furthermore, 45 patients un

Moreover, 99mTc-pertechnetate scan pre-examination preparation is relatively simple and does not need intestinal cleaning preparation. Therefore, it has certain advantages in diagnosing MD bleeding, consistent with literature reports[7]. 99mTc has a special affinity for particular cells of gastric mucosa, which can be ingested, utilized, and secreted by gastric mucosa; 99mTc-Pertechnetate salt scanning can detect abnormal isotope concentration of gastric mucosa outside the stomach by high-resolution gamma ray, which has high accuracy in diagnosing symptomatic MD. In patients with active intestinal bleeding, scintillation of suspected Meckel’s radionuclides can detect diverticulum as its source[17]. Additionally, our positive rate of DBE diagnosis was 100%, which is significantly better than 99mTc- pertechnetium scan, CE, and small intestine CT examination. DBE is more conducive to MD diagnosis due to its intuitive, omnidirectional, and controllable advantages, with the highest accuracy for diagnosing adult MD bleeding. Therefore, DBE should be the preferred method of preoperative diagnosis, consistent with multi-center studies[16,18].

Herein, 76 patients chose to undergo laparoscopic diverticulectomy; length/width analysis[10] revealed 11 cases of tubular and 65 cases of saccular MD, which suggested that saccular and basal width MD was more likely to be compli

To summarize, the occurrence of MD complicated by bleeding was more prevalent in adolescent men. Additionally, the disease onset tended to manifest at an even younger age. The distal ileum emerged as the most often affected site, whereas basal larger diverticula were more prone to complications involving bleeding. Notably, diverticular mucosal ulcers were identified as the primary etiological factor contributing to bleeding in MD cases. Concurrent hemorrhage in MD patients presents as the passage of dark red bloody stool without accompanying abdominal discomfort. Following the occurrence of bleeding, the evaluation of the shock index reveals a value significantly lower than 1. Most MD patients experiencing hemorrhage can undergo preoperative diagnosis using DBE. Therefore, MD bleeding should be highly suspected in young men with first-time or recurrent passing dark red blood stool without abdominal pain. DBE can be used as the preferred inspection and should be immediately arranged through anal DBE inspection. Furthermore, a 99m

Due to the lack of specific symptoms and signs of bleeding caused by Meckel’s diverticulum (MD), preoperative diagnosis is difficult, and it is easy to be clinically misdiagnosed or even missed. As double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) is a highly precise examination method in MD diagnosis, the study aims to analyze the characteristic clinical manifestations of patients with intestinal disease MD complicated with digestive tract hemorrhage; as well as to evaluate the value of DBE in MD diagnosis and the prognosis after laparoscopic diverticula resection.

The study investigated the prevalent population of MD in a retrospective study to guide early screening and preventive treatment for high-risk individuals; explore the causes of bleeding in MD to facilitate early preventive measures, compare the advantages of DBE with other examination methods to assist in the rational formulation of clinical diagnosis and treatment strategies; and evaluating the therapeutic effectiveness of laparoscopic resection of MD and further exploring more optimal treatment approaches.

The study objectives were to analyze the diagnostic value of DBE in patients with MD and bleeding.

The study retrospectively analyzed relevant data from 84 MD patients between January 2015 and March 2022 and recorded their clinical manifestations, auxiliary examination, and follow-up after laparoscopic diverticula resection. The clinical data of 84 patients diagnosed with MD and hemorrhage by DBE and other auxiliary examinations (small intestine CT, nuclide scan, and CE) in the past 7 years were retrospectively analyzed. A dual-balloon colonoscopy system (EN-450P5, a diagnostic endoscope, or 450T5, a therapeutic endoscope) was used. Clinical data were collected and analyzed, which included sex, age, bleeding characteristics, blood routine, biochemical indicators, coagulation function test, imaging or endoscopy, postoperative pathological examination, and follow-up results.

Firstly, MD with bleeding was more common in young men, and was mostly manifested as dark red bloody stool, with less bleeding. Secondly, we combined the endoscopic manifestations with the pathological results of patients with MD complicated by bleeding. It was found that combined ulcer was the main cause of MD bleeding. The formation of ulcer and mucosal layer hyperplasia were related to gastric mucosa/pancreatic tissue, which guided clinicians to be aware of gastric mucosa/pancreatic tissue heterotopic. Thirdly, this study found that DBE and 99mTc-pertechnetate scanning had obvious advantages for the diagnosis of MD complicated with bleeding, and laparoscopic surgical resection for MD complicated with bleeding could obtain a better prognosis, guiding clinicians to make the best choice in diagnosis and treatment.

This study showed that MD with bleeding was more common in young men, and most patients presented with dark red stool defecation. Following the occurrence of bleeding, the evaluation of the shock index revealed a value significantly less than 1, thus most patients with hemorrhage tolerated DBE examination. DBE was used as the first choice for exa

The small intestine is currently a blind spot for most examination methods. DBE addresses this gap. At our center, it has been observed that a significant portion of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding is often associated with small intestine diseases. MD is the most common cause of small intestine bleeding. Clearly defining the diagnostic role of DBE in small intestine diseases is beneficial for formulating rational clinical diagnosis and treatment plans.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sugimoto M, Japan S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Uppal K, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, Shaffer K, Loukas M. Meckel's diverticulum: a review. Clin Anat. 2011;24:416-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kelynack TN. Cases of Meckel's Diverticulum. J Anat Physiol. 1892;26:554-555. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Çelebi S. Male predominance in Meckel's diverticulum: A hyperacidity hypotheses. Med Hypotheses. 2017;104:54-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hochain P, Colin R. [Epidemiology and etiology of acute digestive hemorrhage in France]. Rev Prat. 1995;45:2277-2282. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Editorial Board of the Chinese Digestive Journal. Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal bleeding. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2018;9:577-582. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Yamamoto H, Ell C, Binmoeller KF. Double-balloon endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2008;40:779-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang R, Wang Y, Li D, Yu L, Liu G, Ma J, Wang W. Application of carbon nanoparticles to mark locations for re-inspection after colonic polypectomy. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1530-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Emergency Physicians Branch of Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Emergency Medicine Branch of Chinese Medical Association; Professional committee of emergency medicine of the whole Army Chinese Association of Emergency Medicine; Beijing Society of Emergency Medicine. Expert consensus on emergency diagnosis and treatment of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Zhongguo Zhongzheng Yixue Zazhi. 2021;41:1-10. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Group of Small Bowel Endoscopy and Capsule Endoscopy; Chinese Society of Digestive Endoscopy. Chinese guideline for clinical application of enteroscopy. Zhonggou Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2018;35:693-702. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Duan X, Ye G, Bian H, Yang J, Zheng K, Liang C, Sun X, Yan X, Yang H, Wang X, Ma J. Laparoscopic vs. laparoscopically assisted management of Meckel's diverticulum in children. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:94-100. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Chen Y, Tang YH, Hu CH, Jiang XC. CT Enterography Classification of Symptomatic Meckel’ s Diverticulum. Hanshao Jibing Zazhi. 2021;28:79-83. |

| 12. | Lu L, Yang C, He T, Bai X, Fan M, Yin Y, Wan P, Tang H. Single-centre empirical analysis of double-balloon enteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of small bowel diseases: A retrospective study of 466 cases. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:7503-7510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hansen CC, Søreide K. Systematic review of epidemiology, presentation, and management of Meckel's diverticulum in the 21st century. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | He Q, Zhang YL, Xiao B, Jiang B, Bai Y, Zhi FC. Double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis of Meckel's diverticulum: comparison with operative findings and capsule endoscopy. Surgery. 2013;153:549-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Raghoebir L, Biermann K, Buscop-van Kempen M, Wijnen RM, Tibboel D, Smits R, Rottier RJ. Disturbed balance between SOX2 and CDX2 in human vitelline duct anomalies and intestinal duplications. Virchows Arch. 2013;462:515-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hong SN, Jang HJ, Ye BD, Jeon SR, Im JP, Cha JM, Kim SE, Park SJ, Kim ER, Chang DK. Diagnosis of Bleeding Meckel's Diverticulum in Adults. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parra-Fariñas C, Quiroga-Gomez S, Castro-Boix S, Vallribera-Valls F, Castellà-Fierro E. Computed tomography of complicated Meckel's diverticulum in adults. Radiologia (Engl Ed). 2019;61:297-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Krstic SN, Martinov JB, Sokic-Milutinovic AD, Milosavljevic TN, Krstic MN. Capsule endoscopy is useful diagnostic tool for diagnosing Meckel's diverticulum. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:702-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |