Published online Mar 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.731

Peer-review started: January 12, 2024

First decision: January 31, 2024

Revised: February 5, 2024

Accepted: February 27, 2024

Article in press: February 27, 2024

Published online: March 27, 2024

Processing time: 70 Days and 7.5 Hours

Hemorrhoids are among the most common and frequently encountered chronic anorectal diseases in anorectal surgery. They are venous clusters formed by con

To assess the factors influencing pain scores and quality of life (QoL) in patients with mixed hemorrhoids post-surgery.

The clinical data of patients with mixed hemorrhoids who underwent Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy were collected retrospectively. The basic characteristics of the enrolled patients with mixed hemorrhoids were recorded, and based on the Goligher clinical grading system, the hemorrhoids were classified as grades III or IV. The endpoint of this study was the disappearance of pain in all patients. Quantitative data were presented as mean ± SD, such as age, pain score, and QoL score. Student’s t-test was used to compare the groups.

A total of 164 patients were enrolled. The distribution of the visual analog scale pain scores of all patients at 3, 7, 14 and 28 d after surgery showed that post-surgery pain was significantly reduced with the passage of time. Fourteen days after the operation, the pain had completely disappeared in some patients. Twenty-eight days after the surgery, none of the patients experienced any pain. Comparing the World Health Or

Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy can significantly improve the postoperative QoL of patients. Age, sex, and the number of surgical resections were important factors influencing Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy.

Core Tip: Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy improves postoperative quality of life in patients with mixed hemorrhoids. Factors such as age, sex, and number of surgical resections influence the outcome of the procedure. Post-surgery pain decreases over time, with complete pain disappearance observed in some patients after 14 d. Quality-of-life scores significantly improve after surgery, particularly in physical and psychological health, social relations, and surrounding environment. This study highlights the positive impact of Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy on patients' quality of life and emphasizes the importance of considering various factors during the procedure.

- Citation: Sun XW, Xu JY, Zhu CZ, Li SJ, Jin LJ, Zhu ZD. Analysis of factors impacting postoperative pain and quality of life in patients with mixed hemorrhoids: A retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(3): 731-739

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i3/731.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.731

Hemorrhoids are among the most common and frequently encountered chronic anorectal diseases in anorectal surgery[1]. They are venous clusters formed by congestion, expansion, and flexion of the venous plexus in the lower part of the rectum[2]. The symptoms of hemorrhoids include bright red bleeding from the anus and intestines, mucus discharge, perianal irritation or itching, pain around the anus, hemorrhoid pad prolapse or protruding masses, and staining of the underwear[3]. Hemorrhoids affect 4.40% of the global population, with a global incidence of approximately 49.14%[4]. In China, 51.14% adults of the total surveyed population suffer from anorectal diseases, where hemorrhoids constitute the highest incidence rate (50.28%)[5]. According to the Goligher clinical grading system, hemorrhoids are classified as grades I–IV[6]. Grades I and II can usually be controlled with conservative treatment, while Grades III and IV often re

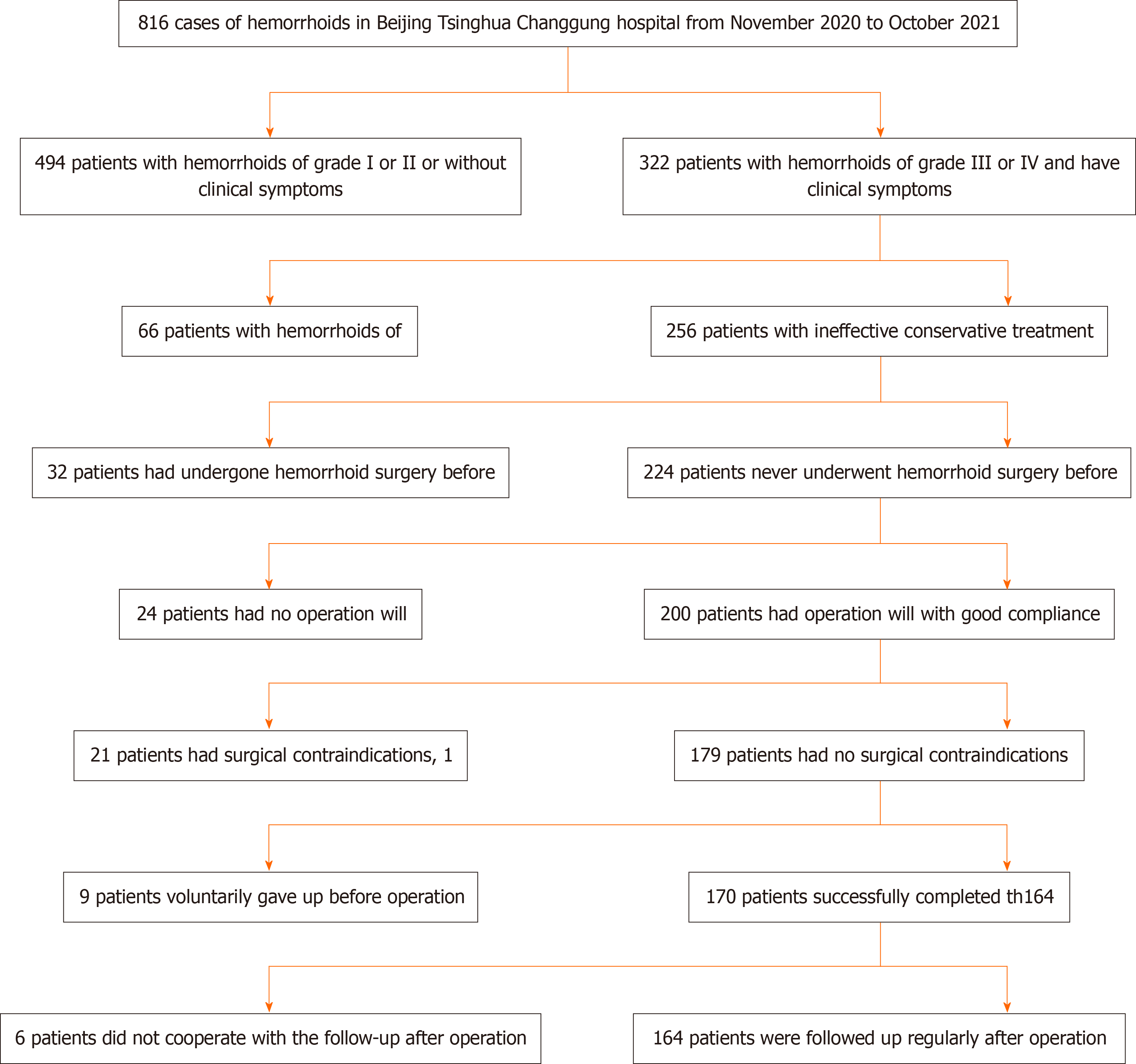

This was a retrospective study involving patients with mixed hemorrhoids (grade III or IV). All patients underwent external pile-excision and internal pile-ligature operations for mixed hemorrhoid treatment in Beijing Tsinghua Chang

Inclusion criteria: The following inclusion criteria were applied in this study: (1) Patients who were diagnosed with mixed hemorrhoids (grades III and IV) based on the Goligher clinical grading system for the classification of he

Exclusion criteria: The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who have had mixed hemorrhoids surgery or other perianal disease surgery before; (2) Patients who had severe systemic diseases or severe primary diseases (such as cardiac, cerebrovascular, hepatic, renal, or hematopoietic system diseases); (3) Patients who had severe mental illness, such as severe depression or mania; (4) Patients who were either pregnant, breastfeeding or were women experiencing menstrual periods; (5) Patients with rectal cancer, tuberculosis, Crohn's disease and other rectal and anal diseases; (6) Patients with allergies; or (7) Patients who voluntarily abandoned treatment prior to surgery.

Surgical method: We employed Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy to remove mixed hemorrhoids.

Observational indicators and follow up: The observational indicators for this study were as follows: (1) Improvement in pain post-surgery; (2) Changes in quality-of-life post-surgery. The patients were observed for 28 d after surgery. At 3, 7, 14, and 28 d after surgery, the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) of pain intensity was used to assess the pain levels of patients. At 14- and 28-d post-surgery, the World Health Organization Quality of Life – BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) self-reporting questionnaire was used to assess the quality of life (QoL) of patients. At 3-, 7-, and 14-d post-surgery, the patients did not undergo digital rectal examination to avoid suture tearing. At 28 d post-surgery, we evaluated the treatment effect by using a digital rectal examination.

Data were processed by using the SPSS 27 software (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data, such as age, pain scores, and QoL scores, were presented as mean ± SD. The Student’s t-test was used to compare the groups. Factors influencing postoperative pain and the WHOQOL-BREF scores were analyzed by using multiple linear regression. All P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

A total of 164 patients were included in this study. The basic patient information is shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Data |

| Age (yr) | 39.9 ± 13.0 |

| < 60 | 146 (89.0) |

| ≥ 60 | 18 (11.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 93 (56.7) |

| Female | 71 (43.3) |

| Anesthesia mode | |

| Local anesthesia | 15 (9.2) |

| Intrathecal anesthesia | 137 (83.5) |

| General anesthesia | 12 (7.3) |

| Number of surgical resection | |

| 1 | 36 (22.0) |

| 2 | 66 (40.2) |

| 3 | 62 (37.8) |

The distribution of the VAS-based pain scores of all patients at 3, 7, 14 and 28 d after surgery are shown in Table 2. Post-surgery pain was significantly reduced with the passage of time. Fourteen days after the operation, the pain had completely disappeared in some patients. Twenty-eight days after the surgery, none of the patients experienced any pain.

| Time | Score | Number of patients |

| 3 d | 3 | 24 |

| 4 | 87 | |

| 5 | 53 | |

| 7 d | 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 65 | |

| 3 | 79 | |

| 4 | 16 | |

| 14 d | 0 | 20 |

| 1 | 95 | |

| 2 | 49 | |

| 28 d | 0 | 164 |

Comparing the WHOQOL-BREF scores of patients at 14 and 28 d after surgery, we used one-way repeated measures analysis of variance and determined whether there is a significant improvement in the QoL of patients at 14 and 28 d after surgery. According to the boxplot, there were no outliers in the data. According to the Shapiro-Wilk test, the data of each group followed a normal distribution (P > 0.05); According to the Mauchly spherical hypothesis test, the variance-co

| Item | Time | mean ± SD | t value | P value |

| Quality of life | 14 d after operation | 3.79 ± 0.57 | 25.087 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | 4.79 ± 0.46 | |||

| Health condition | 14 d after operation | 4.01 ± 0.62 | 17.174 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | 4.80 ± 0.41 | |||

| Physical health | 14 d after operation | 23.41 ± 2.85 | 80.282 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | 32.10 ± 2.96 | |||

| Psychological health | 14 d after operation | 21.37 ± 1.70 | 78.541 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | 27.22 ± 1.62 | |||

| Social relation | 14 d after operation | 6.32 ± 1.66 | 81.973 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | 12.21 ± 1.59 | |||

| Surrounding environment | 14 d after operation | 28.42 ± 2.86 | 80.092 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | 37.13 ± 2.88 |

| Item | Time | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients (Beta) | t value | P value | |

| B | SE | |||||

| Constant | 3 d after operation | 4.430 | 0.163 | - | 27.219 | < 0.001 |

| 7 d after operation | 2.954 | 0.189 | - | 15.648 | < 0.001 | |

| Age | 3 d after operation | -0.033 | 0.003 | -0.581 | -11.404 | < 0.001 |

| 7 d after operation | -0.030 | 0.003 | -0.512 | -8.884 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | 3 d after operation | -0.220 | 0.076 | -0.149 | -2.902 | 0.004 |

| 7 d after operation | -0.275 | 0.088 | -0.182 | -3.134 | 0.002 | |

| Anesthesia mode | 3 d after operation | -0.044 | 0.065 | -0.035 | -0.678 | 0.499 |

| 7 d after operation | -0.097 | 0.075 | -0.074 | -1.283 | 0.201 | |

| Number of surgical resections | 3 d after operation | 0.428 | 0.049 | 0.442 | 8.695 | < 0.001 |

| 7 d after operation | 0.365 | 0.057 | 0.367 | 6.390 | < 0.001 | |

Multiple linear regression analysis of the WHOQOL-BREF scores at 14 and 28 d after mixed hemorrhoid surgery showed that age and sex, but not anesthesia mode and number of surgical resections (P > 0.05), were the factors in

| Item | Time | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients (Beta) | t value | P value | |

| B | SE | |||||

| Constant | 14 d after operation | 27.493 | 0.856 | - | 32.135 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | 37.129 | 0.828 | - | 44.863 | < 0.001 | |

| Age | 14 d after operation | -0.110 | 0.015 | -0.505 | -7.342 | < 0.001 |

| 28 d after operation | -0.134 | 0.015 | -0.590 | -9.199 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | 14 d after operation | 0.867 | 0.398 | 0.151 | 2.178 | 0.031 |

| 28 d after operation | 1.092 | 0.385 | 0.183 | 2.837 | 0.005 | |

| Anesthesia mode | 14 d after operation | 0.255 | 0.342 | 0.051 | 0.747 | 0.456 |

| 28 d after operation | 0.223 | 0.331 | 0.043 | 0.675 | 0.501 | |

| Number of surgical resection | 14 d after operation | -0.052 | 0.259 | -0.014 | -0.199 | 0.842 |

| 28 d after operation | -0.098 | 0.250 | -0.025 | -0.393 | 0.695 | |

Hemorrhoids is a benign but commonly occurring chronic disease that can disrupt the daily lives and well-being of pa

One of the major purposes of our study was to assess the factors influencing the QoL of patients after hemorr

In a longitudinal observational study, bleeding and soiling showed significant improvements in symptom severity from weeks 4 to 8 post-surgery, whereas pain, itching, and swelling/prolapse did not[15]. This difference in the impro

Keong et al[15] found pain, bleeding, soiling, itching, and swelling/prolapse to be the factors that affect the QoL of patients. In the present study, we found that age, sex, and number of resections were factors affecting the QoL of patients. We also found that age, sex, and number of resections were risk factors for postoperative pain after hemorrhoidectomy using the Milligan-Morgan procedure. The subjective feelings of patients were used as the main option in this study. Postoperative pain after Milligan–Morgan hemorrhoidectomy remains a problem for colorectal surgery teams[17]. Pa

A retrospective cohort association study[18] has indicated that postoperative pain decreases with increasing age. A total of 11510 patients from 26 countries (59% women; mean age 62 years) underwent one of the aforementioned types of surgery. These results are consistent with those of the present study.

In our study, we found that men experienced pain more intensely than women. Psychological factors such as anxiety, distress, and pain catastrophizing play relevant roles in the development of pain after surgery[19]. Hormones may possibly mediate the role of sex differences in post-surgical pain by contributing to fluctuations in pain sensitivity across the menstrual cycle in women[20]. Furthermore, in 58 studies (published between September 2013 and March 2015) assessing sex differences in patients undergoing various surgical procedures, women seemed to be at a higher risk of developing severe postoperative pain[21].

As the number of excisions increased, pain increased. Hemorrhoidectomy may partially injure the submucosal plexus along with the underlying muscles and alter the neuroregulation of the rectal muscles, leading to rectal hyperactivity and spasms. We found that the more tissue was removed, the more likely the anus was to develop swelling.

Our study found that neither QoL nor postoperative pain was affected by the mode of anesthesia. In a report from Nigeria[22], 22 (18.3%) patients consented to undergo ligation and excisional hemorrhoidectomy under local anesthesia. As many as 88 (73.3%) patients were managed conservatively, eight (6.7%) had surgery under spinal anesthesia and two (1.7%) patients had surgery under general anesthesia. Surgeries done under local anesthetic have some important ad

This study demonstrated that Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy can significantly improve the postoperative QoL of patients. Age, sex, and the number of surgical resections were the factors that influenced postoperative pain but were not related to the anesthesia mode. With an increase in illness duration, the number of mixed hemorrhoids gradually in

Hemorrhoids are a common chronic anorectal disease characterized by the formation of venous clusters in the lower part of the rectum. Mixed hemorrhoids, in particular, often cause recurrent bleeding and can lead to severe anemia, negatively impacting the patient's health. Surgical treatment, such as Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy, is often necessary. How

This study provides valuable information on improving surgical outcomes and postoperative care for patients with mixed hemorrhoids.

This study aimed to assess the factors influencing pain scores and QoL in patients with mixed hemorrhoids post-surgery.

This retrospective study collected clinical data from patients with mixed hemorrhoids who underwent Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy. The basic characteristics of the enrolled patients with mixed hemorrhoids were recorded, and based on the Goligher clinical grading system, the hemorrhoids were classified as grades III or IV.

The results showed a significant reduction in postoperative pain over time, with some patients experiencing complete pain relief at 14 d and none reporting any pain at 28 d after surgery. Comparing the QoL scores between 14 and 28 d post-surgery, significant improvements were observed in various domains including overall QoL, health condition, physical health, psychological health, social relations, and surrounding environment. Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy was found to significantly improve the postoperative QoL for patients.

Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy offers a promising approach for alleviating the negative impact of mixed hemorrhoids on patients' health and QoL.

Several perspectives can be considered for future studies on mixed hemorrhoids and Milligan-Morgan hemorr

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shimada H, Japan S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Ryan P. Observations upon the aetiology and treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Aust N Z J Surg. 1980;50:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wilson MZ, Swarup A, T Wilson LR, Ivatury SJ. The Effect of Nonoperative Management of Chronic Anal Fissure and Hemorrhoid Disease on Bowel Function Patient-Reported Outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1223-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Idrees JJ, Clapp M, Brady JT, Stein SL, Reynolds HL, Steinhagen E. Evaluating the Accuracy of Hemorrhoids: Comparison Among Specialties and Symptoms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:867-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shiels MS, Kreimer AR, Coghill AE, Darragh TM, Devesa SS. Anal Cancer Incidence in the United States, 1977-2011: Distinct Patterns by Histology and Behavior. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1548-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Buntzen S, Christensen P, Khalid A, Ljungmann K, Lindholt J, Lundby L, Walker LR, Raahave D, Qvist N; Danish Surgical Society. Diagnosis and treatment of haemorrhoids. Dan Med J. 2013;60:C4754. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hull TL. Surgery of the anus, rectum and colon. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1173-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang H, Gu Y, Ji L, Li Y, Xu S, Guo T, Xu M. A new mixed surgical treatment for grades iii and iv hemorrhoids: modified selective hemorrhoidectomy combined with complete anal epithelial retention. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2021;34:e1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:741-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Yang JY, Peery AF, Lund JL, Pate V, Sandler RS. Burden and Cost of Outpatient Hemorrhoids in the United States Employer-Insured Population, 2014. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:798-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Joshi GP, Neugebauer EA; PROSPECT Collaboration. Evidence-based management of pain after haemorrhoidectomy surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1155-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Megari K. Quality of Life in Chronic Disease Patients. Health Psychol Res. 2013;1:e27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee JH, Kim HE, Kang JH, Shin JY, Song YM. Factors associated with hemorrhoids in korean adults: korean national health and nutrition examination survey. Korean J Fam Med. 2014;35:227-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Holzheimer RG. Hemorrhoidectomy: indications and risks. Eur J Med Res. 2004;9:18-36. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Szyca R, Leksowski K. Assessment of patients' quality of life after haemorrhoidectomy using the LigaSure device. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2015;10:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Keong SYJ, Tan HK, Lamawansa MD, Allen JC, Low ZL, Østbye T. Improvement in quality of life among Sri Lankan patients with haemorrhoids after invasive treatment: a longitudinal observational study. BJS Open. 2021;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xia W, Barazanchi AWH, MacFater W, Sammour T, Hill AG. Day case versus inpatient stay for excisional haemorrhoidectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:E5-E9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Medina-Gallardo A, Curbelo-Peña Y, De Castro X, Roura-Poch P, Roca-Closa J, De Caralt-Mestres E. Is the severe pain after Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy still currently remaining a major postoperative problem despite being one of the oldest surgical techniques described? A case series of 117 consecutive patients. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:73-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Dijk JFM, Zaslansky R, van Boekel RLM, Cheuk-Alam JM, Baart SJ, Huygen FJPM, Rijsdijk M. Postoperative Pain and Age: A Retrospective Cohort Association Study. Anesthesiology. 2021;135:1104-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ip HY, Abrishami A, Peng PW, Wong J, Chung F. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 739] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1928] [Cited by in RCA: 1855] [Article Influence: 115.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pereira MP, Pogatzki-Zahn E. Gender aspects in postoperative pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:546-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Alatise OI, Agbakwuru AE, Takure AO, Adisa AO, Akinkuolie AA. Open haemorrhoidectomy under local anaesthesia for symptomatic haemorrhoids: An experience from Nigeria. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2011;12:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sajid MS, Bhatti MI, Caswell J, Sains P, Baig MK. Local anaesthetic infiltration for the rubber band ligation of early symptomatic haemorrhoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Updates Surg. 2015;67:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |