Published online Feb 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i2.609

Peer-review started: October 8, 2023

First decision: December 6, 2023

Revised: December 17, 2023

Accepted: January 15, 2024

Article in press: January 15, 2024

Published online: February 27, 2024

Processing time: 138 Days and 5.4 Hours

Infected acute necrotic collection (ANC) is a fatal complication of acute pancreatitis with substantial morbidity and mortality. Drainage plays an exceedingly important role as the first step in invasive intervention for infected necrosis; however, there is great controversy about the optimal drainage time, and better treatment should be explored.

We report the case of a 43-year-old man who was admitted to the hospital with severe intake reduction due to early satiety 2 wk after treatment for acute pancreatitis; conservative treatment was ineffective, and a pancreatic pseudocyst was suspected on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). Endoscopic ultra

Early EUS-guided aspiration and lavage combined with late ERCP catheter drainage may be effective methods for intervention in infected ANCs.

Core Tip: Infected acute necrotic collection (ANC) is a potentially fatal disease. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle aspiration is recommended when the diagnosis is unclear. Endoscopic drainage is the optimal treatment for infected necrosis and is generally performed 4 wk after onset. Herein, we present a case in which an infected ANC was misdiagnosed as a pancreatic pseudocyst and was successfully treated by early EUS-guided aspiration and lavage combined with late endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography catheter drainage. EUS-guided aspiration and lavage may be used as a bridge while waiting for the necrotic collection to be fully encapsulated before draining.

- Citation: Zhang HY, He CC. Early endoscopic management of an infected acute necrotic collection misdiagnosed as a pancreatic pseudocyst: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(2): 609-615

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i2/609.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i2.609

Acute necrotic collections (ANCs) form within the first 4 wk of necrotizing pancreatitis and contain varying amounts of fluid and necrotic pancreas and peripancreatic tissue and are often accompanied by a rupture of the main pancreatic duct and increased susceptibility to infection[1]. Infection of ANCs can be diagnosed either by radiologically demonstrated ‘bubbles’ or by positive Gram staining or culture via fine-needle aspiration (FNA)[2]. Compared to imaging, FNA has a greater diagnostic yield, but its use for purely diagnostic purposes is not recommended, as it is adopted only when a definitive diagnosis cannot be made[3,4].

Drainage is the first step of invasive intervention for infected necrosis. However, there is a lack of consensus on the optimal timing of intervention, and the guidelines recommending delayed intervention are mainly drawn from studies in the era of surgical necrosectomy and lack evidence from prospective studies[5,6]. In this study, we present a case in which an infected ANC was misdiagnosed as a pancreatic pseudocyst (PPC), which was diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA (EUS-FNA) and successfully treated by early EUS-guided aspiration and lavage combined with late endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatic duct stent drainage. This endoscopic combination therapy is feasible for infected ANCs when the collection communicates with the pancreatic duct and has never been described before.

We report the case of a 43-year-old man who was admitted to our hospital with severe intake reduction due to early satiety.

The patient complained of severe abdominal pain, accompanied by nausea and vomiting, after heavy consumption of spirits with a high alcohol concentration 20 d prior. The local hospital diagnosed acute pancreatitis. After receiving medical treatment, such as medications to inhibit acid and inhibit pancreatic enzyme secretion, the patient was discharged with improvement. However, two weeks later, the patient experienced severe intake reduction due to early satiety and left upper abdominal pressure, and computed tomography (CT) showed multiple pseudocysts around the pancreas. The local hospital diagnosed PPC, and conservative treatment was ineffective.

He had no previous history of gallstones.

The patient had a history of drinking more than 20 years and drank approximately 500 mL/d of high-concentration liquor.

The left upper abdomen showed a large mass with clear boundaries and poor motion.

The patient’s leukocyte count was 9.72 × 109/L, his neutrophil ratio was 77.5%, and his C-reactive protein level was 73.49 mg/L. His pancreatic amylase level was slightly elevated (84 μ/L), while his blood amylase level was within normal limits.

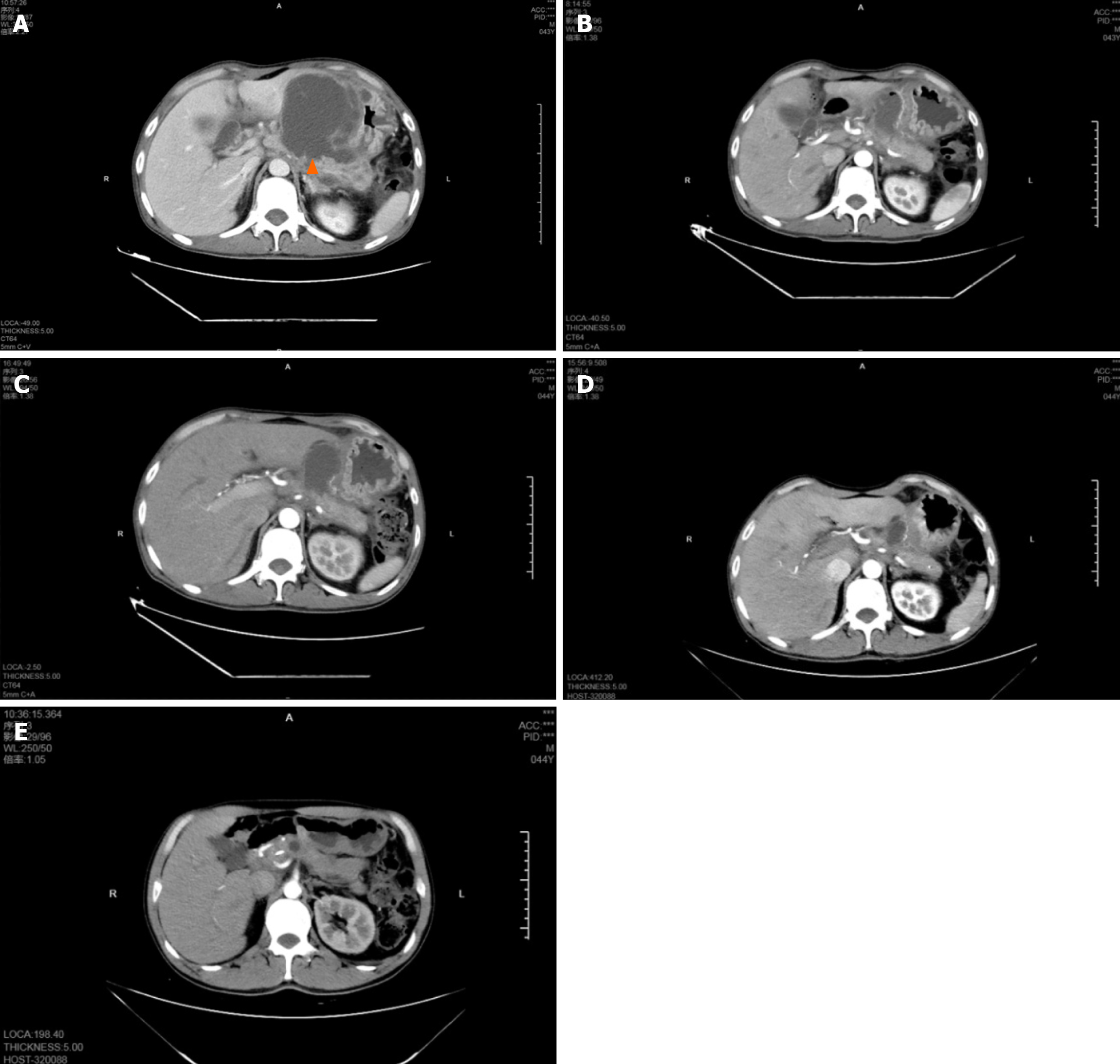

On 13 February 2023, contrast-enhanced CT showed multiple cystic foci in the abdominal cavity and low-attenuated, homogeneous fluid collections, with a maximum diameter of 89 mm × 76 mm (Figure 1A).

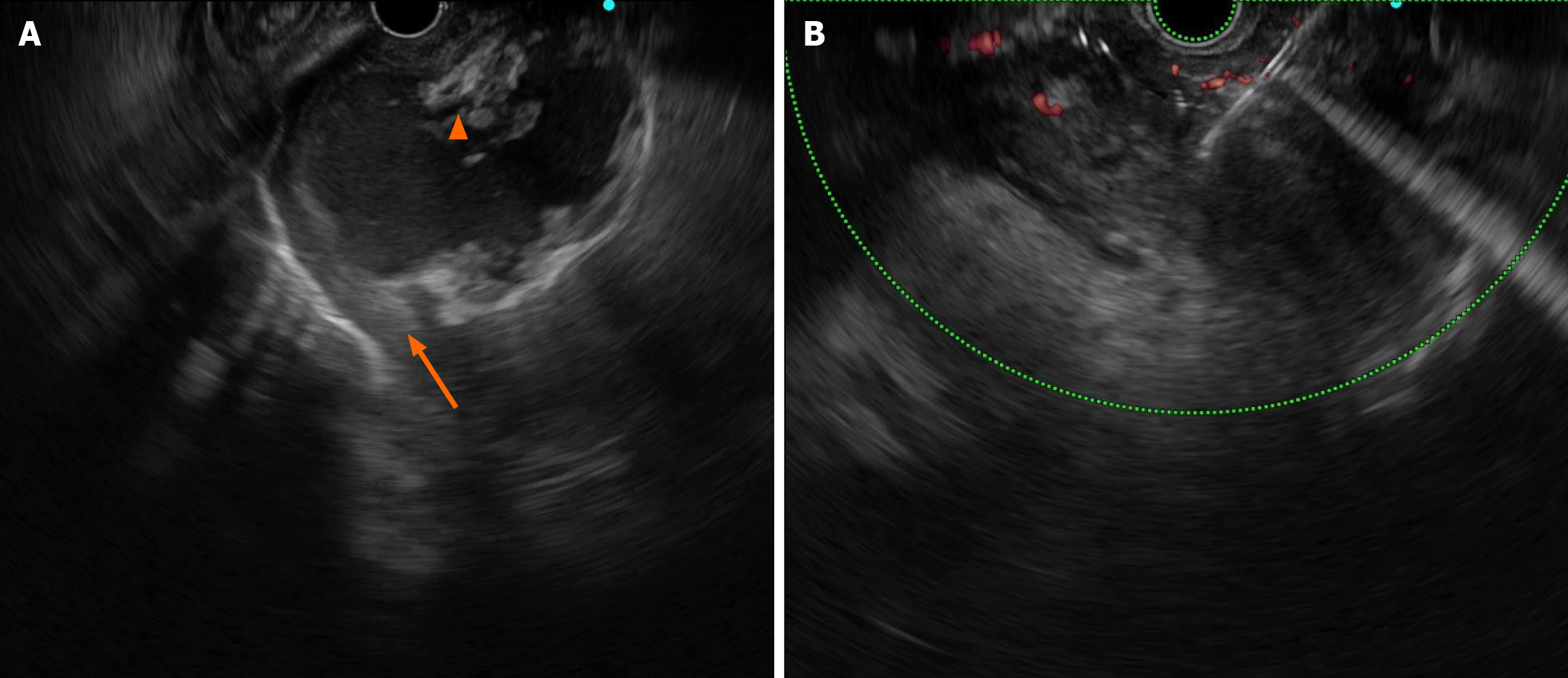

EUS revealed multiple cystic masses with hyperechoic necrosis and arterial vessels, the maximum size of the cysts was 56 mm × 36 mm, and the necrotic collection was not completely wrapped (Figure 2A).

We invited the director of the Gastroenterology Department of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University and the director of the Radiology Department of our hospital to participate in a multidisciplinary discussion. The onset time of acute pancreatitis was less than 4 wk, and EUS confirmed that the cystic cavity contained necrotic debris and that the collection was not completely wrapped; thus, ANC was performed. The patient had signs of gastrointestinal outlet obstruction, such as a severe eating disorder caused by early satiety. Conservative medical treatment was ineffective, so there were indications of invasive treatment intervention. The collection mixture was not completely encapsulated; therefore, EUS-guided aspiration and lavage were recommended to relieve the symptoms of compression. An unexpected finding was observed when the CT was reread, as the cyst was connected to the pancreatic duct (Figure 1A). Therefore, ERCP catheter drainage could be performed after the collection was completely encapsulated.

EUS-FNA revealed exudate, and his lactate dehydrogenase level was 16228.9 U/L. Culture revealed A-haemolytic Streptococcus, so he was ultimately diagnosed with ANC infection.

On 19 February 2023, the first intervention was performed under intubation anaesthesia. EUS-guided puncture extracted a small amount of bloody fluid, approximately 50 mL in total, and the cystic cavity almost completely disappeared after several repeated rinses with sterile saline, and the procedure was considered a smooth procedure (Figure 2B).

The postoperative compression symptoms were significantly relieved without fever, bleeding or other discomfort. CT examination 3 d after surgery showed that the pancreatic cyst was substantially reduced, with a maximum diameter of approximately 40 mm × 59 mm (Figure 1B).

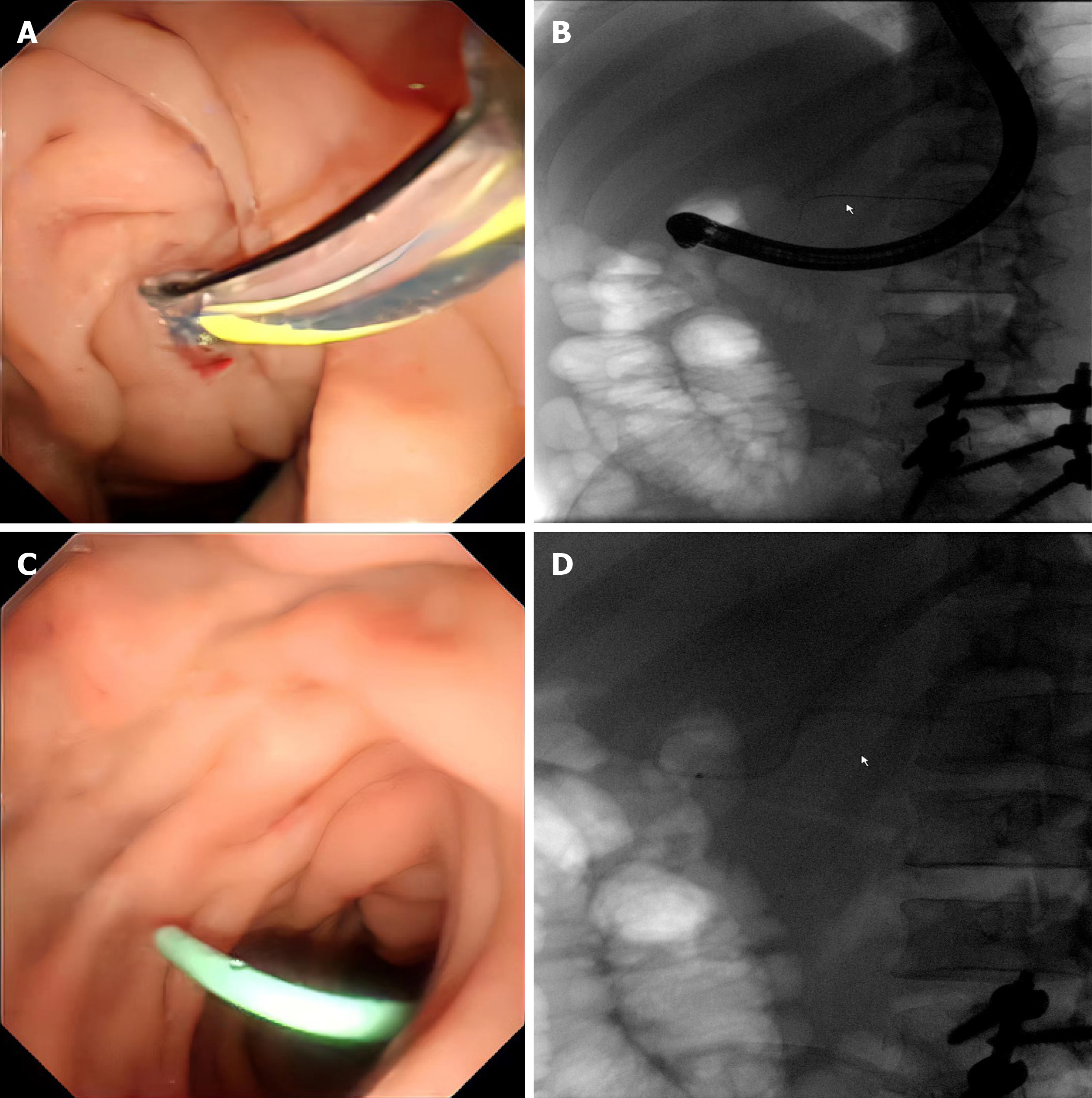

Two weeks later, CT examination revealed that the cyst size was similar to that at the last examination (Figure 1C); therefore, we conducted another intervention, catheter drainage through ERCP. After intubation and general anaesthesia, the gastroscope was passed smoothly through the oesophageal and stomach cavities. The papilla was found on the medial part of the descending duodenum, and the guidewire was inserted into the pancreatic duct through an incision that was made with a knife. The pancreatic duct was not dilated under fluoroscopy, and a 5-7 Fr plastic pancreatic stent was placed on the main pancreatic duct. Endoscopic drainage was smooth, and the X-ray fluoroscopy stent was in a good position (Figure 3).

The patient recovered well and was successfully discharged 3 d later. The outpatient follow-up showed no obvious discomfort, and CT examination after 3 months indicated that the pancreatic cyst was substantially smaller than before, with a maximum diameter of 27 mm × 22 mm (Figure 1D). CT reexamination at 6 months after surgery showed that the cyst had basically disappeared (Figure 1E).

Approximately 10%-20% of acute pancreatitis cases progress to necrotizing pancreatitis, and one-third of these patients develop secondary infections[2,7]. Infected necrosis is associated with high morbidity and mortality and usually occurs after 3-4 wk or earlier in acute pancreatitis but is rare within 1 wk[2,5,8]. The diagnosis of infected necrosis is critical. Signs of infectious necrosis include new or persistent sepsis, clinical worsening despite adequate support, and no other source of infection[1]. CT or magnetic resonance imaging occasionally reveals gas within (peri-) pancreatic collections, which is present in almost 42% of patients[9]. For patients whose imaging diagnosis is difficult, EUS-FNA can be used, but it is not recommended for diagnosis only and is usually performed before endoscopic drainage[3,4]. In our case, the patient had no fever, his inflammatory serum markers were slightly elevated, and there was a lack of bubble signs on CT, making it easy to misdiagnose. Therefore, in patients with atypical clinical symptoms and CT findings suggestive of PPC, physicians should be alert to infected necrosis when conservative medical treatment is ineffective, and EUS-FNA is recommended for definitive diagnosis.

According to the 2012 revised Atlanta Classification, pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) are classified into 4 categories according to the time of onset and histological features: Acute peripancreatic fluid collections, ANCs, PPCs and walled-off necrosis[2]. Most aseptic PFCs resolve spontaneously without intervention. However, when the patient has refractory abdominal pain; symptoms of gastrointestinal obstruction, such as nausea, vomiting, or early satiety; signs of infection; or signs of obstruction of the biliary tract, drainage is recommended[10].

The treatment strategies for infected necrosis have undergone a shift from open surgery to minimally invasive surgery to step-up therapy[11,12]. Drainage is an extremely important first step in invasive intervention, and studies have shown that approximately half of patients recover with drainage, avoiding the need for necrosectomy[13]. However, the optimal drainage procedure is controversial, and prospective studies are lacking. International guidelines recommend that drainage, either percutaneous or transluminal, be performed after 4 wk when the collection is walled off[6,14]. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that early intervention is associated with increased mortality[15]. Nevertheless, the American College of Gastroenterology recommends that drainage be performed when infected necrosis is confirmed, and percutaneous drainage should be given priority in the acute stage (first 2 wk)[16].

Both percutaneous drainage and endoscopic drainage are first-line treatments for fluid collection[5]. In this patient, the pancreatic cyst was close to the gastric wall, so endoscopic transmural drainage was preferred. However, EUS revealed that the collections were not completely encapsulated or liquefied; therefore, drainage was abandoned, and aspiration and lavage were performed as transitional treatments. These interventions help to relieve symptoms, control infection and lay the foundation for subsequent treatment.

Pancreatic cysts are classified into seven types based on their anatomical location in relation to the main pancreatic duct[17]. ERCP drainage can be performed only in patients with small (< 5 cm) cysts communicating with the pancreatic duct[18]. ERCP pancreatic duct stent placement is the cornerstone of treatment for pancreatic duct leakage. Many studies have suggested the effectiveness of transpapillary drainage for the treatment of pancreatic cysts, and this approach is conducive to promoting leakage closure[19,20]. The most common complications were acute pancreatitis, stent-induced scarring of the main pancreatic duct and infection[1]. In our case, the collection was connected to the pancreatic duct and was significantly reduced by the first intervention; therefore, we adopted ERCP catheter drainage after the collection was fully walled off, avoiding pancreatic fistula and puncture bleeding compared to percutaneous and transmural drainage.

Early endoscopic diagnosis and treatment play important roles in the prognosis of infected patients with necrosis. For the first time, we successfully used EUS-guided aspiration and lavage combined with ERCP catheter drainage for the treatment of infected ANCs, avoiding debridement and poor outcomes. EUS-guided aspiration and lavage may be used as a bridge before drainage and provide clinicians with a new idea for the management of infected necrosis.

The authors would like to thank the participants for their help.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Amante MF, Argentina; Donato G, Italy S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ

| 1. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Muthusamy VR, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, Bruining DH, Chathadi KV, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Fonkalsrud L, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Kothari S, Lightdale JR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Shaukat A, Wang A, Yang J, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4338] [Article Influence: 361.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 3. | Chahal P, Baron TH, Topazian MD, Levy MJ. EUS-guided diagnosis and successful endoscopic transpapillary management of an intrahepatic pancreatic pseudocyst masquerading as a metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:393-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heo J. Infected Pancreatic Necrosis Mimicking Pancreatic Cancer. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:436-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Trikudanathan G, Wolbrink DRJ, van Santvoort HC, Mallery S, Freeman M, Besselink MG. Current Concepts in Severe Acute and Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1994-2007.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Timing of catheter drainage in infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:306-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, Besselink MG, Ahmed Ali U, Schrijver AM, Boermeester MA, van Goor H, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, van Ramshorst B, Schaapherder AF, van der Harst E, Hofker S, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Brink MA, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, Cuesta MA, Wahab PJ, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1254-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | van Grinsven J, van Brunschot S, van Baal MC, Besselink MG, Fockens P, van Goor H, van Santvoort HC, Bollen TL; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Natural History of Gas Configurations and Encapsulation in Necrotic Collections During Necrotizing Pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:1557-1564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | van Baal MC, Bollen TL, Bakker OJ, van Goor H, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, Gooszen HG, van der Harst E, van Eijck CH, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. The role of routine fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery. 2014;155:442-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bhakta D, de Latour R, Khanna L. Management of pancreatic fluid collections. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ramai D, Morgan AD, Gkolfakis P, Facciorusso A, Chandan S, Papaefthymiou A, Morris J, Arvanitakis M, Adler DG. Endoscopic management of pancreatic walled-off necrosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2023;36:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yasuda I, Takahashi K. Endoscopic management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Baal MC, van Santvoort HC, Bollen TL, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Systematic review of percutaneous catheter drainage as primary treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2011;98:18-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arvanitakis M, Dumonceau JM, Albert J, Badaoui A, Bali MA, Barthet M, Besselink M, Deviere J, Oliveira Ferreira A, Gyökeres T, Hritz I, Hucl T, Milashka M, Papanikolaou IS, Poley JW, Seewald S, Vanbiervliet G, van Lienden K, van Santvoort H, Voermans R, Delhaye M, van Hooft J. Endoscopic management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines. Endoscopy. 2018;50:524-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nakai Y, Shiomi H, Hamada T, Ota S, Takenaka M, Iwashita T, Sato T, Saito T, Masuda A, Matsubara S, Iwata K, Mukai T, Isayama H, Yasuda I; WONDERFUL study group in Japan. Early versus delayed interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. DEN Open. 2023;3:e171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baron TH, DiMaio CJ, Wang AY, Morgan KA. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update: Management of Pancreatic Necrosis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:67-75.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 83.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Nealon WH, Walser E. Main pancreatic ductal anatomy can direct choice of modality for treating pancreatic pseudocysts (surgery versus percutaneous drainage). Ann Surg. 2002;235:751-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nabi Z, Lakhtakia S. Endoscopic management of chronic pancreatitis. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:1059-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lin H, Zhan XB, Jin ZD, Zou DW, Li ZS. Prognostic factors for successful endoscopic transpapillary drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:459-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Larsen M, Kozarek R. Management of pancreatic ductal leaks and fistulae. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1360-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |