Published online Oct 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3350

Revised: August 22, 2024

Accepted: August 29, 2024

Published online: October 27, 2024

Processing time: 82 Days and 1.1 Hours

Acute gastric volvulus represents a rare form of surgical acute abdomen, which makes it difficult to establish an early diagnosis. As the disease progresses, it can lead to gastric ischemia, necrosis, and other serious complications.

This paper reports a 67-year-old female patient with a history of abdominal distension and retching for 1 day. After admission, a prompt and thorough exami

Patients with gastric torsion combined with free gas in the abdominal cavity should consider nongastrointestinal perforation factors to avoid misdiagnosis.

Core Tip: In this case, a 67-year-old female was admitted to the hospital due to abdominal distension and pain. The initial diagnosis was acute gastric torsion accompanied by free gas in the abdominal cavity. This makes it easy for us to determine the presence of gastric perforation. However, the patient's physical examination and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan did not support the diagnosis of gastric perforation. After endoscopic reduction of gastric torsion, we found that the patient also had a colonic gas cyst after reexamination via CT. This is a rare case that has not been reported before.

- Citation: Zhang Q, Xu XJ, Ma J, Huang HY, Zhang YM. Acute gastric volvulus combined with pneumatosis coli rupture misdiagnosed as gastric volvulus with perforation: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(10): 3350-3357

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i10/3350.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3350

Gastric torsion is a rare form of surgical acute abdomen with a difficult diagnosis, especially when patients are accom

A 67-year-old female was admitted with a complaint of abdominal distension for 1 day.

The patient had sudden epigastric distension and pain 1 day prior, accompanied by nausea and retching, no hematemesis or melena, reduced anal exhaust, defecation once during the disease, and no relief from abdominal distension after fasting.

No history of hypertension or diabetes, gastritis or gastric ulcer, or abdominal surgery.

No family history of any genetic disease.

The left upper quadrant was distended, the gastric type was palpable, there was no tenderness or rebound tenderness in the abdomen, there were no signs of peritoneal irritation, and there were 3 bowel sounds/min.

Routine blood tests, C-reactive protein levels, liver function tests, and renal function tests were all within the normal range.

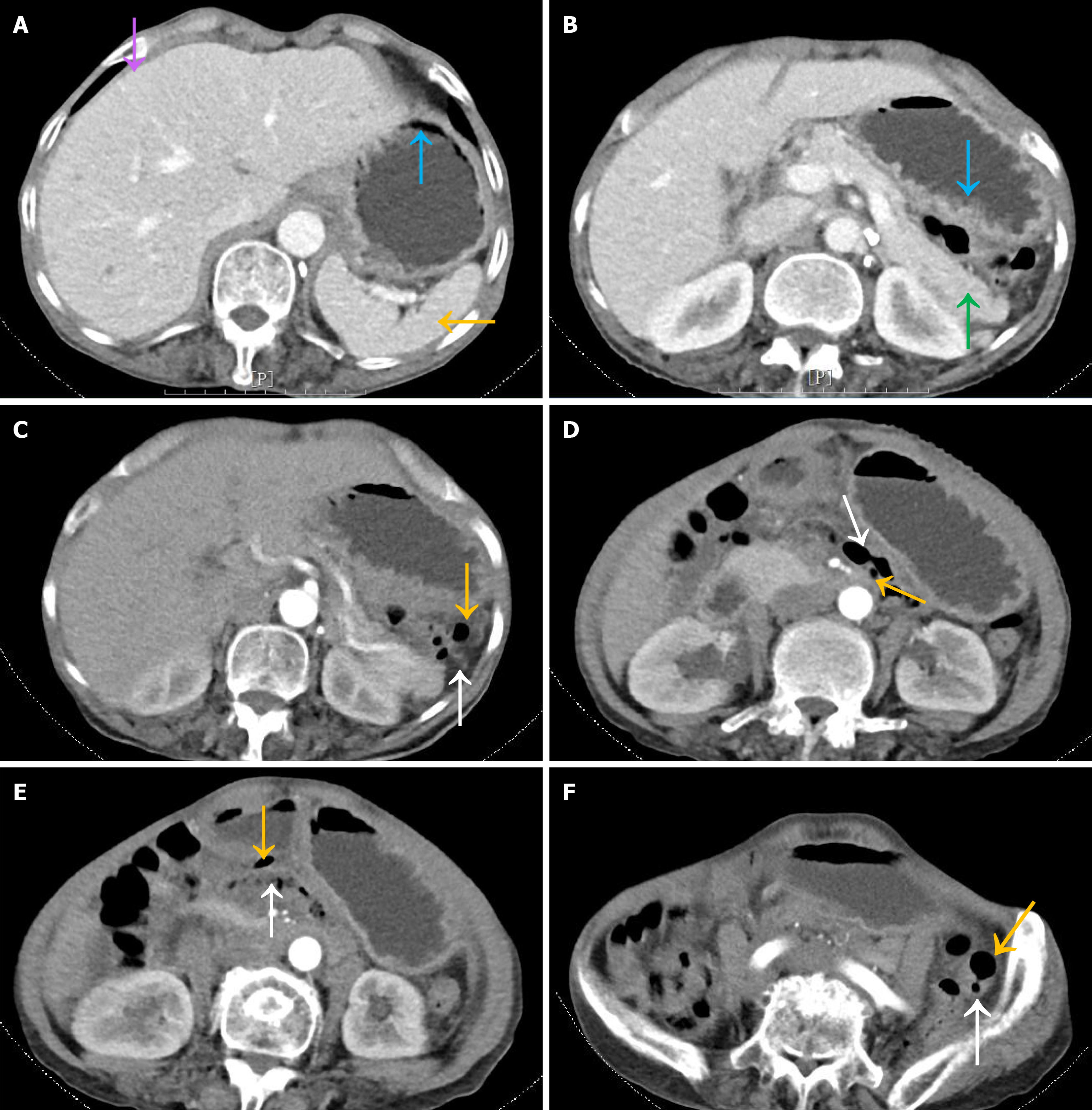

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed acute gastric dilatation, with the lower edge of the stomach extending to the plane of the anterior superior iliac spine. The antrum was located in the anterosuperior cardia, and the spleen had shifted to the upper margin of the pancreas. Free air was noted within the abdominal cavity, and there was no effusion in the abdominal cavity or pelvic cavity. The placed gastric tube bypassed the gastric body through the posterior aspect of the stomach (Figure 1).

Emergency gastroscopy revealed deformity of the gastric lumen, accumulation of a large amount of food debris, patchy mucosal congestion, and ulceration in the gastric body, and it was difficult to identify the angle and antrum along the gastric body (Figure 2).

Gastrointestinal meglumine diatrizoate contrast examination revealed crescent-shaped free air under the diaphragm, an inflated and dilated gastric lumen, and high fluid levels. The cardia was displaced to the lower left, the gastric angle was not visualized, and the greater and lesser curvatures were indistinct. Partial entry of the contrast agent into the duodenum was observed, and the shape of the duodenal bulb was normal (Figure 3).

The final diagnosis was gastric torsion combined with a ruptured colonic gas cyst.

On the basis of the patient’s medical history, physical examination, and imaging examination findings, a diagnosis of acute gastric volvulus with free air in the abdominal cavity was established. The presence of free air in the abdominal cavity of the patient influenced treatment decision-making. Surgical exploration or laparoscopic exploration was considered the first choice for treatment, but considering the absence of the peritoneal irritation sign, lack of effusion on the abdominal and pelvic CT, and insufficient evidence of gastric perforation, we first performed endoscopic reduction after communicating with the family members of the patient.

The patient underwent gastroscopy again, and the antrum and pylorus were the same as those in the first gastroscopy. We changed the patient’s position to the right lateral decubitus position after removing the gastric effusion and food debris. After repeated inflation, the antrum was successfully observed, and weentered the duodenum. Complete exploration of the entire gastric cavity revealed scattered ulcers predominantly in the gastric body; the antrum, pylorus, and duodenal mucosa appeared smooth, with no evidence of neoplasms (Figure 4).

After endoscopic reduction, the patient’s abdominal signs were observed. The patient had no abdominal pain, and her abdominal distension substantially improved. The patient was treated with proton pump inhibitors and asked to fast for 1 day. Abdominal-enhanced CT was reexamined on the second day after endoscopic treatment. Upon reexamination via CT, the stomach and spleen returned to normal positions, the shape of the stomach was normal, the free air in the abdominal cavity disappeared, and there was no effusion in the abdominal cavity or pelvic cavity. There were no mass lesions in the gastric wall, spleen, or pancreas. Moreover, we found segmented scattered cystic air areas in the colon of the patient after medical images were reviewed carefully (Figure 5). The patient was on a liquid diet, transitioned to a normal diet without abdominal discomfort, and was discharged uneventfully.

At the 6-month follow-up, the patient had a normal diet and reported no abdominal pain or distension and normal anus exhaust and regular bowel movements.

Gastric volvulus refers to the abnormal rotation of the entire stomach or a part of the stomach around an axis > 180°, resulting in a closed-loop obstruction. This is a rare, life-threatening disease. Berti first reported this phenomenon during the autopsy of a 61-year-old woman in 1866 and revealed that the peak age of onset was 40-60 years, with cases also reported in infants younger than 1 year. It mainly presents as acute or chronic recurrent gastrointestinal obstruction, and severe cases can progress to gastric strangulation, necrosis, perforation, and hypovolemic shock[1].

Acute gastric volvulus is characterized by the sudden onset of severe epigastric pain, accompanied by upper abdomen distension and a soft, flat lower abdomen. Additional symptoms may include dyspnea, vomiting, and aggravation of symptoms after meals. To facilitate diagnosis, Borchardt proposed the triad of gastric volvulus in 1904: (1) Severe epigastric pain and distension; (2) Vomiting, which in turn results in severe retching; and (3) Difficulty in gastric tube insertion, which is observed in up to 70% of patients with acute gastric volvulus[2]. Subsequently, Carter further pro

In this case, the patient had a history of abdominal distension and pain, vomiting, and other accompanying symptoms. The physical examination revealed a palpable distended gastric area, and the clinical symptoms were consistent with the clinical manifestations of gastric volvulus. Imaging studies, including abdominal CT, gastrointestinal radiography, and gastroscopy, revealed a distorted and distended gastric shape. The antrum and pylorus could not be visualized endo

The treatment plan was developed after consulting with the patient’s family, with a preference for endoscopic reduction therapy. However, emergency surgical exploration could have been performed if the condition of the patient deteriorated. During the endoscopic procedure, the patient’s body position was adjusted to promote the reduction of the stomach’s size and volume by gravity and gastric cavity inflation in the right lateral decubitus position. Abdominal massage was used to assist in endoscopic treatment. Throughout the procedure, the gastric cavity returned to a normal microscopic state, and the morphology of the antrum and duodenum was observed without any complications. The patient did not report abdominal pain, and there were no signs of peritonitis in the abdomen. On the second day after treatment, enhanced abdominal CT revealed that the shape of the stomach returned to normal, with the surrounding organs reverting to their normal anatomical position. No space-occupying lesions were observed in the gastric wall, and there were no defects in the diaphragm.

Another concern in this case is the source of free air in the patient’s peritoneal cavity. The most common source of free air in the abdominal cavity is perforation of hollow organs in the abdominal cavity. Typically, patients present with acute manifestations of peritonitis, including signs of peritoneal irritation[7]. The diagnosis of gastric volvulus was confirmed. The first considered diagnosis was gastric volvulus accompanied by gastric perforation, suggesting the need for emer

To summarize the diagnosis and treatment process of this case, the patient had no previous history of abdominal surgery or other factors, the cause of the gastric volvulus was considered to be primary gastric volvulus, and the exact cause of the volvulus remained unclear. Following successful endoscopic treatment and a favorable outcome during the 6-month follow-up period, with the patient exhibiting normal eating habits and no recurrence of symptoms, additional laparoscopic exploration, gastric fixation, and other surgical methods were not deemed necessary.

Acute gastric dilatation represents a rare but surgical acute abdomen, necessitating early diagnosis and treatment, with some cases requiring emergency surgical treatment and some cases successfully managed through endoscopic treatment. The presence of free air in the abdominal cavity is commonly associated with the perforation of hollow organs of the abdominal cavity, but it can also arise from nondigestive tract perforations, and intestinal air cysts are rare. When both diseases cooccur, they pose a challenge for clinicians in making treatment decisions and require clinicians to be good at differential diagnosis.

| 1. | Lopez PP, Megha R. Gastric Volvulus. 2022 Nov 7. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Karande TP, Oak SN, Karmarkar SJ, Kulkarni BK, Deshmukh SS. Gastric volvulus in childhood. J Postgrad Med. 1997;43:46-47. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Carter R, Brewer LA 3rd, Hinshaw DB. Acute gastric volvulus. A study of 25 cases. Am J Surg. 1980;140:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Omata J, Utsunomiya K, Kajiwara Y, Takahata R, Miyasaka N, Sugasawa H, Sakamoto N, Yamagishi Y, Fukumura M, Kitagawa D, Konno M, Okusa Y, Murayama M. Acute gastric volvulus associated with wandering spleen in an adult treated laparoscopically after endoscopic reduction: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2016;2:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cantone N, Gulia C, Miele V, Trinci M, Briganti V. Wandering Spleen and Organoaxial Gastric Volvulus after Morgagni Hernia Repair: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Surg. 2016;2016:6450765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | El-Magd EA, Elgeidie A, Abbas A, Elmahdy Y, LotfyAbulazm I, Hamed H. Laparoscopic approach in the management of diaphragmatic eventration in adults: gastrointestinal surgical perspective. Updates Surg. 2024;76:555-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hoshino N, Endo H, Hida K, Kumamaru H, Hasegawa H, Ishigame T, Kitagawa Y, Kakeji Y, Miyata H, Sakai Y. Laparoscopic Surgery for Acute Diffuse Peritonitis Due to Gastrointestinal Perforation: A Nationwide Epidemiologic Study Using the National Clinical Database. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2022;6:430-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | De Waele J, Lipman J, Sakr Y, Marshall JC, Vanhems P, Barrera Groba C, Leone M, Vincent JL; EPIC II Investigators. Abdominal infections in the intensive care unit: characteristics, treatment and determinants of outcome. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Friedrich K, Nüssle S, Rehlen T, Stremmel W, Mischnik A, Eisenbach C. Microbiology and resistance in first episodes of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: implications for management and prognosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1191-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |