Published online Oct 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3343

Revised: September 6, 2024

Accepted: September 14, 2024

Published online: October 27, 2024

Processing time: 113 Days and 3.5 Hours

Thrombocytopenia is a common complication of invasive liver abscess syndrome (ILAS) by Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) infection, which indicates severe infection and a poor prognosis. However, the presence of leukopenia is rare. There are rare reports on leukopenia and its clinical significance for ILAS, and there is currently no recognized treatment plan. Early and broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy may be an effective therapy for treating ILAS and improving its prognosis.

A 55-year-old male patient who developed fever, chills, and abdominal distension without an obvious cause presented to the hospital for treatment. Laboratory tests revealed thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and multiple organ dysfunction. Imaging examinations revealed an abscess in the right lobe of the liver and thromboph

Leukopenia is a rare complication of ILAS, which serves as an indicator of adverse prognostic outcomes and the severity of infection.

Core Tip: Thrombocytopenia is a common complication of invasive liver abscess syndrome (ILAS). However, there have been no reports of concurrent leukopenia with ILAS so far. This patient presented with a sustained high fever, abdominal distension, and pain after hospitalization. He subsequently developed multiple organ and system dysfunction, as well as an atypical leukopenia coexisting with thrombocytopenia. These features are often used as indicators of the severity of the disease. Klebsiella pneumoniae was detected on blood cultures, and antibiotics were adjusted timely based on drug sensitivity test results. After systemic support and blood glucose management treatment, the patient’s condition resolved. Early antimicrobial therapy is an effective measure to control infection and improve prognosis.

- Citation: Niu CY, Yao BT, Tao HY, Peng XG, Zhang QH, Chen Y, Liu L. Leukopenia-a rare complication secondary to invasive liver abscess syndrome in a patient with diabetes mellitus: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(10): 3343-3349

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i10/3343.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3343

Invasive liver abscess syndrome (ILAS) comprises a liver abscess caused by hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp) and metastatic infections in multiple extrahepatic organs such as the brain, lungs, and eyes. ILAS is a severe clinical condition with a global mortality rate of approximately 2%-19%[1]. Clinical symptoms include fever and chills, abdo

Intestinal hvKp, which is the main pathogen implicated in ILAS, invades the liver by passing through the intestinal barrier or via retrograde entry into the liver. It then enters the portal vein circulation[3], leading to bacteraemia and sepsis. Haematological findings of ILAS typically include an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and decreased platelet count[6]. To the best of our knowledge, ILAS with concurrent leukopenia has not yet been reported.

Fever accompanied by abdominal distension for 3 days.

A 55-year-old man with a 3-day history of fever and abdominal distension was admitted to our hospital (No. 698690). He also experienced chills, headaches, and abdominal pain. He denied any history of systemic and ocular diseases. On admission, his fever was remittent and fluctuated between 37.5 °C and 40.5 °C. Conjunctival congestion and tenderness in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant were also detected.

He was previously healthy.

Previously healthy with no history of special illnesses.

Temperature 37.7 °C, pulse 113 times/minute, respiratory rate 18 times/minute, blood pressure 107/74 mmHg, height 170 cm, weight 70 Kg. The patient was alert, awake, and oriented, with no signs of an altered level of consciousness. He had palpable enlargement of the superficial lymph nodes and coarse respiratory sounds in both lungs. His heart rate was 113 beats per minute, the rhythm was regular, no murmurs were heard on auscultation of the heart, the abdomen was flat and soft, mild tenderness was found in the upper and middle upper abdomen, there was no rebound pain or pain upon percussion of the liver area, and auscultation of bowel sounds revealed four bowel sounds per minute.

Blood routine and inflammatory markers: Laboratory tests revealed significantly increased high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and procalcitonin levels, as well as reduced platelet counts of 70 × 109/L (reference range: 100 × 109/L to 300 × 109/L) and WBC counts of 3.76 × 109/L (reference range: 4 × 109/L to 10 × 109/L) (Table 1).

| Date | WBC (4 × 109-10 × 109/L) | N% (50%-70%) | PLT (100 × 109-300 × 109/L) | HrCRP (0-10 mg/L) | IL-6 (< 7 pg/mL) | PCT-GN (< 0.5 ng/mL) |

| March, 04 2024 | 3.76 | 87.8 | 80 | 145.76 | 331.51 | 15.806 |

| March, 06 2024 | 2.5 | 74 | 70 | 61.77 | 24.47 | 5.402 |

| March, 09 2024 | 7.25 | 81.2 | 71 | 27.98 | 16.08 | 3.563 |

| March, 12 2024 | 6.76 | 74.1 | 302 | 11.81 | 7.07 | 0.484 |

| March, 15 2024 | 5.55 | 80.5 | 219 | 50.36 | 36.22 | 1.176 |

| March, 18 2024 | 5.86 | 75 | 259 | 31.52 | 8.01 | 0.85 |

| April, 29 2024 | 4.21 | 32.2 | 194 | 0.68 | < 1 | < 0.02 |

Urinalysis: Urine specific gravity 1.04 (1.003-1.030), urine protein + +, glucose ±, albumin 150 mg/L (0.0-23.8), urine protein/creatinine 0.15 (0.000–0.030).

Blood biochemistry testing: The fasting blood glucose, postprandial glucose, and HbA1c levels were 8.2 mmol/L, 13.8 mmol/L, and 6.2%, respectively. Additional laboratory test results revealed liver and kidney dysfunction, electrolyte imbalances, and an abnormal coagulation profile. The respective detection result values were as follows: Total bilirubin (TBIL) 45.6 μmol/L (3.4-20.5), direct bilirubin 20.8 μmol/L (0.0-6.8), alanine aminotransferase 57.2 U/L (0-40), aspartate transaminase 48.4 U/L (0-40), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase 247 U/L (8.0-58.0), creatinine 114.7 μmol/L (58.3-106.0), sodion (Na+) 132.8 mmol/L (136.0-146.0), chloridion (Cl-) 93.3 mmol/L (101.0-109.0), phosphorus 0.59 mmol/L (0.81-1.45), fibrinogen 5 g/L (2.0-4.0), antithrombin III 80.9% (80.0-120.0), D-dimer 3.67 μg/mL (0-0.55), and fibrinogen degradation products 12.3 μg/mL (0-5.0). These abnormal results indicate that multiple organ functions have been injured. Infectious disease screening yielded negative results for respiratory pathogen immunoglobulin M, hepatitis virus, anti-human im

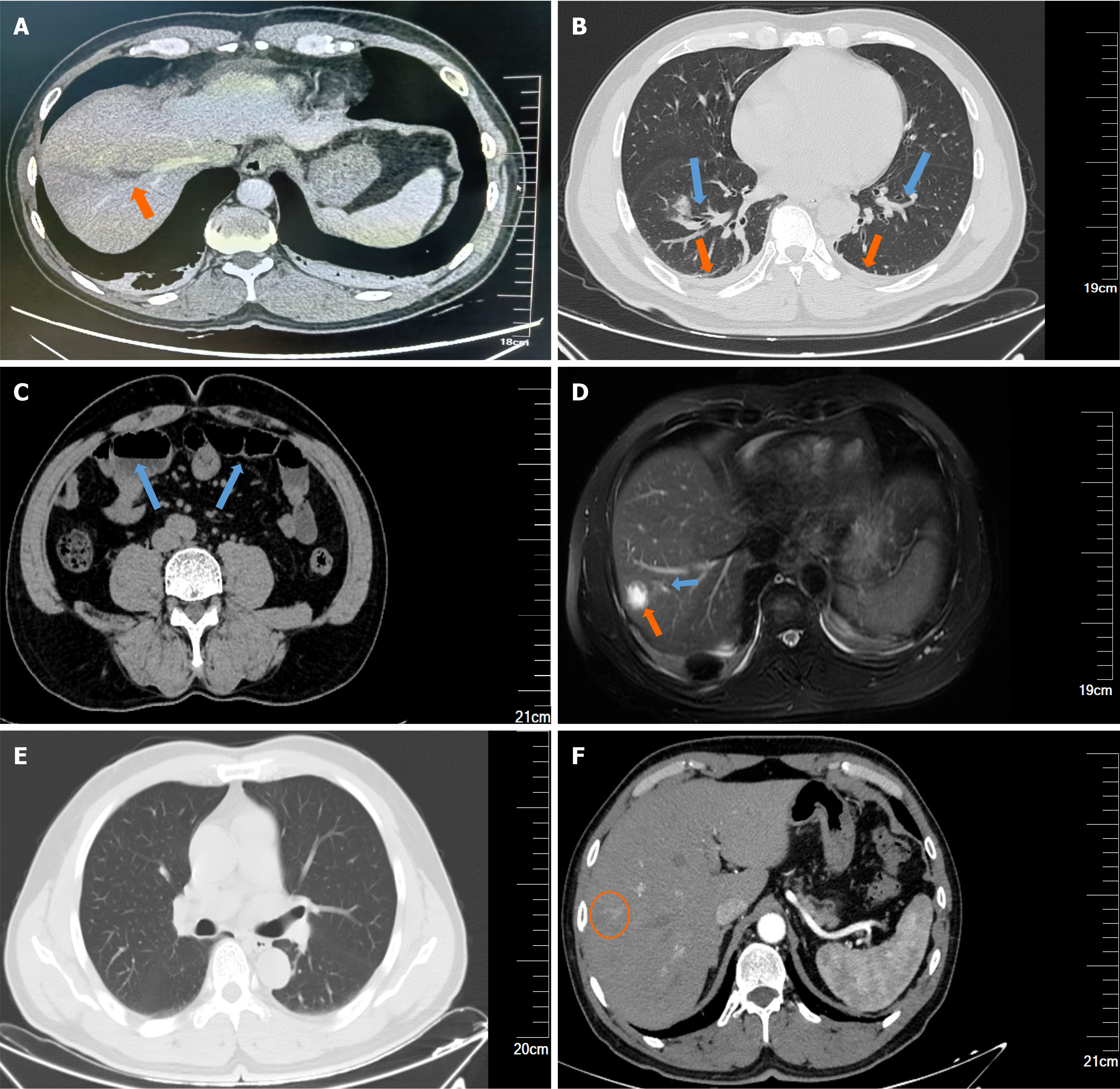

Chest and abdominal computed tomography (plain scan + enhancement) revealed two pneumonia cases, bilateral pleural effusions, small intestinal fluid accumulation in the lower abdomen with slight dilation of the intestinal tract, and a possible abscess in the right lobe of the liver (Figure 1A-C).

Upper abdominal magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a right lobe liver abscess, adjacent sup

Experts participating in the multidisciplinary consultation came from the following departments: Imaging Department, Respiratory Department, infectious diseases Department, Interventional Department, Laboratory Department and General Surgery Department.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with hvKp caused ILAS secondary to diabetes mellitus and leu

After the patient was admitted, he received the immediate empirical antibiotic piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5 g every 8 hours), intensive blood glucose control, and supportive treatment. On day 3 of admission, his condition worsened, and the WBC and platelet counts further decreased to 2.50 × 109/L and 65 × 109/L, respectively. After pathogen culture co

After 2 weeks of comprehensive treatment, the patient did not experience any further fever, his symptoms improved, and all examination findings had improved. At the 56-day follow-up, the patient did not experience any discomfort, and physical examination revealed no obvious abnormalities. All laboratory tests were normal, including fasting blood glucose (5.6 mmol/L) and HbA1c (5.9%). Imaging results revealed complete resolution of thrombophlebitis and granulomatous changes following the liver abscess (Figure 1E and F). Thus, we concluded that we had successfully treated this patient, and he had a good prognosis.

Poor glycaemic control damages neutrophil phagocytic function and promotes the growth of pathogens in tissues, ulti

Thrombophlebitis and liver abscesses are distinctive imaging features of ILAS. Potential mechanisms include hvKp endotoxin-induced hypercoagulability and blood flow stasis from venous drainage of the abscess, direct inflammation-induced thrombosis, and coagulopathy with an elevated D-dimer level[7,8]. Thrombophlebitis is a marker of haematogenous dissemination that involves multiple organs and increases clinical complexity and mortality risk.

The haematological findings of ILAS include leucocytosis and thrombocytopenia[9]. Thrombocytopenia is associated with infection and exacerbated severity[8] and is an independent risk factor for invasive syndromes in patients with th

Our patient experienced 4 days of leukopenia, which has not been previously reported in the literature. The following possible mechanisms were suggested for the patient’s prolonged leukopenia: Severe gram-negative K. pneumoniae infe

Compared with the general population, individuals with diabetes are more prone to infection, the infection process is more complex, and the infection is more likely to become severe[13]. The main mechanisms causing this result include: (1) High blood glucose causing inhibition of immune cell activity [such as cluster of differentiation (CD) 4, CD8, and na

In terms of immunity, the function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is inhibited, and the adhesion, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis of WBCs are reduced. Additionally, with a background of diabetes and metabolic disorders, the persistent low-grade inflammation, the imbalance in gut microbiota, and the impairment of intestinal barrier function may increase the risk of bacteria entering the blood from the intestinal tract[13].

There are no specific guidelines or consensus to address ILAS treatment. Antibiotic therapy is the primary treatment for most ILAS cases[10]. After diagnosis and detection of infection metastasis, early identification of the pathogen, selection of antibiotics to which the organism is susceptible[15], and a comprehensive evaluation of extrahepatic abscesses are crucial. Untreated or delayed cases result in a poor prognosis.

Whether anticoagulation therapy is necessary for ILAS with thrombophlebitis is unclear. Molton et al[16] suggested that reperfusion of the affected veins is closely related to the complete resolution of abscesses, and anti-inflammatory drugs can spontaneously resolve most purulent hepatic venous thrombosis cases. Anticoagulant therapy was not ad

ILAS involves an acute onset and rapid progression with a nonspecific clinical presentation and presents diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. These factors suggest a poor prognosis if treatment is not promptly initiated. Thrombocytopenia has been confirmed to be a poor prognostic predictor for ILAS, however, not only the existence of leukopenia but also the coexistence of leukopenia with thrombocytopenia in ILAS is extremely rare. In this case, the patient presented with both leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, which portend an evolution toward a more critical condition. However, we were able to promptly diagnose and successfully cure the patient in this case. Therefore, we considered leukopenia as another poor prognostic predictor apart from thrombocytopenia in ILAS. Early pathogen identification, precise anti-infective treat

| 1. | Chen YC, Lin CH, Chang SN, Shi ZY. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of pyogenic liver abscess: an analysis from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan, 2000-2011. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49:646-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang CG, Wang Y, Duan M, Zhang XY, Chen XY. Klebsiella pneumoniae invasion syndrome: a case of liver abscess combined with lung abscess, endophthalmitis, and brain abscess. J Int Med Res. 2022;50:3000605221084881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jin Q, Zhang X, Yang H, Zhao B, Wang Y. Blindness in Right Eyes after Enema: A Case of Klebsiella pneumoniae-Related Invasive Liver Abscess Syndrome with Endophthalmitis-Caused Blindness as the First Symptom. Case Rep Med. 2024;2024:5573160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee CR, Lee JH, Park KS, Jeon JH, Kim YB, Cha CJ, Jeong BC, Lee SH. Antimicrobial Resistance of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Hypervirulence-Associated Determinants, and Resistance Mechanisms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang H, Xue X. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of pyogenic liver abscess: a retrospective study. J Int Med Res. 2023;51:3000605231180053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jun JB. Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess. Infect Chemother. 2018;50:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iwadare T, Kimura T, Sugiura A, Takei R, Kamakura M, Wakabayashi SI, Okumura T, Hara D, Nakamura A, Umemura T. Pyogenic liver abscess associated with Klebsiella oxytoca: Mimicking invasive liver abscess syndrome. Heliyon. 2023;9:e21537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Feng C, Di J, Jiang S, Li X, Hua F. Machine learning models for prediction of invasion Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome in diabetes mellitus: a singled centered retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen L, Wang H, Wang H, Guo Y, Chang Z. Thrombocytopenia in Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a retrospective study on its correlation with disease severity and potential causes. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1351607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang Y, Chen JH, Chen WL, Chung JY. Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive syndrome with liver abscess and purulent meningitis presenting as acute hemiplegia: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Repsold L, Joubert AM. Platelet Function, Role in Thrombosis, Inflammation, and Consequences in Chronic Myeloproliferative Disorders. Cells. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Akash MSH, Rehman K, Fiayyaz F, Sabir S, Khurshid M. Diabetes-associated infections: development of antimicrobial resistance and possible treatment strategies. Arch Microbiol. 2020;202:953-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Holt RIG, Cockram CS, Ma RCW, Luk AOY. Diabetes and infection: review of the epidemiology, mechanisms and principles of treatment. Diabetologia. 2024;67:1168-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Luo Y, Hu W, Wu L, Duan S, Zhong X. Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive syndrome with liver, lung, and brain abscesses complicated with pulmonary fungal infection: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Emerg Med. 2023;16:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Serban D, Popa Cherecheanu A, Dascalu AM, Socea B, Vancea G, Stana D, Smarandache GC, Sabau AD, Costea DO. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Endogenous Endophthalmitis-A Global Emerging Disease. Life (Basel). 2021;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Molton JS, Chee YL, Hennedige TP, Venkatesh SK, Archuleta S. Impact of Regional Vein Thrombosis in Patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |