Published online Oct 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3288

Revised: July 17, 2024

Accepted: August 23, 2024

Published online: October 27, 2024

Processing time: 145 Days and 14.8 Hours

There is still considerable heterogeneity regarding which features of cryptoglandular anal fistula on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) are relevant to surgical decision-making. As a con

To develop a structured MRI and EAUS template (SMART) reporting the minimum dataset of information for the treatment of anal fistulas.

This modified Delphi survey based on the RAND-UCLA appropriateness for consensus-building was conducted between May and August 2023. One hundred and fifty-one articles selected from a systematic review of the lite

Eleven scientific societies (3 radiological and 8 surgical) endorsed the study. After three rounds of voting, the experts (69 colorectal surgeons, 23 radiologists, 2 anatomists, and 1 gastroenterologist) achieved consensus for 12 of 14 statements (85.7%). Based on the results of the Delphi process, the six following features of anal fistulas were included in the SMART: Primary tract, secondary extension, internal opening, presence of collection, coexisting le

A structured template, SMART, was developed to standardize imaging reporting of fistula-in-ano in a simple, systematic, time-efficient way, providing the minimum dataset of information and visual diagram useful to refer

Core tip: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) are the most used procedures for the preoperative assessment of cryptoglandular anal fistula. A Delphi study was planned. The protocol and the study were approved by 11 international surgical, colorectal, and radiological societies. A Delphi survey achieved 85.7% consensus among radiologists and colorectal surgeons on the minimum dataset of information relevant for decision-making. A structured MRI and EAUS template (SMART) was developed to standardize imaging reporting. This template could help radiologists and surgeons to report MRI and EAUS in a standardized manner.

- Citation: Sudoł-Szopińska I, Garg P, Mellgren A, Spinelli A, Breukink S, Iacobellis F, Kołodziejczak M, Ciesielski P, Jenssen C, SMART Collaborative Group, Santoro GA. Structured magnetic resonance imaging and endoanal ultrasound anal fistulas reporting template (SMART): An interdisciplinary Delphi consensus. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(10): 3288-3300

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i10/3288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3288

Despite developments in surgical techniques for anal fistulas, postoperative recurrence and anal incontinence remain severe complications. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and high-resolution three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound (3D-EAUS) are the most used imaging procedures for treatment planning, providing an accurate spatial assessment of anal fistula[1-4]. Although their diagnostic value has been studied extensively, considerable heterogeneity exists in the literature regarding the information to include in imaging reporting. Radiologists may not be familiar with different surgical techniques nor fistula features that are relevant to decision-making. As a consequence, the quality and comp

This study aimed to develop an evidence-based structured MRI and EAUS anal fistula reporting template (SMART) by an interdisciplinary group of experts using the Delphi process for consensus-building. This template updates previous templates[1,2,5-9], taking into account the new elements of fistula anatomy that have emerged[10,11], new grading systems[11-13], and new surgical procedures introduced[14-18]. The SMART includes the minimum standardized set of information that should be assessed and reported in MRI and EAUS for cryptoglandular anal fistulas as agreed by radiologists and colorectal surgeons (the target audience).

The study protocol was developed according to the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) guidelines development process[19], using a modified Delphi survey based on the RAND-UCLA appropriateness for consensus-building[20] (Supplementary material). This method provides a systematic, structured process to aggregate, evaluate, and summarize scientific evidence in which a majority of experts can converge toward an optimal answer. A multidisciplinary approach approval was not required because the study did not involve patients.

The project was developed in four stages. The full study protocol was sent for review and approval to international radiological and colorectal societies relevant to the topic and content. A call for expressions of interest to take part in the collaborative group was circulated to all members of the societies endorsing the study. Eligibility of experts adhered to the following inclusion criteria modified by Iqbal et al[5]: (1) Peer-reviewed publications in the field in the last 5 years; (2) Practice in a consultant position; (3) Minimum of 10 EAUS/MRI assessments for anal fistula per month; (4) Minimum of 10 years of medical practice; and (5) Absence of potential conflicts of interest. The panel size was set at 100 multidisciplinary experts. The lead investigators of the SMART project (Sudoł-Szopińska I, Garg P, Santoro GA) defined the task group of authors, ensuring a balanced multidisciplinary representation. All experts are listed in the Supplementary material.

Stage 1 (SMART library and kickoff meeting): Selection of potential clinically relevant features of anal fistulas was based on a systematic review of the literature (PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Embase, and World of Science), with a review filter (PubMed), searching the terms: “anal endosonography”, “anal fistula”, “anorectal fistula imaging”, “anorectal fistula surgery”, “EAUS”, “fistula-in-ano”, “pelvic MRI”, “perianal sepsis”. Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, consensus statements, and original scientific articles on the diagnosis and surgical treatment of anal fistula were included. Correspondence commentary, case reports, articles with insufficient data reported, and papers that could not be retrieved were excluded. Selected papers were archived in a cloud-based directory accessible to all panelists (https://www.dropbox.com/sh/thre93x5m7pht85/AAD5BMBSvoubR1ekACcnB_mZa?dl=0) and formed the database (SMART library) to generate the evidence-base around individual items for the Delphi.

The online launch meeting was scheduled to present the leaders, the task group of authors, the group of panelists, and the international scientific societies endorsing the study. Aims and objectives, the Delphi methodology (Supplementary material), and the outline of the project were discussed. Panelists were asked to implement and update the SMART li

Stage 2 (preparation of the Delphi questionnaire): The second online meeting with the SMART collaborators was scheduled to present the final version of the digital SMART library, including additional references proposed by the panelists. The preliminary list of questions for the Delphi process was presented and discussed among the experts, allowing them to comment on the items included to ensure they fully align with the purpose and scope of the research.

Stage 3 (three rounds of Delphi): The task group of authors produced the statements for each question followed by a short discussion and key supporting references from the SMART library, each graded for quality using the Oxford evidence levels (LEs) (https://www.cebm.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CEBM-Levels-of-Evidence-2.1.pdf). If the available literature was limited or of low quality, the statements were based on expert opinion of good practice.

The third online meeting was scheduled to present the final questionnaire accessible to all panelists using a secure online platform (survey administration software, https://www.docs.google.com/forms). Participants were asked to vote anonymously for each statement using a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 reflecting complete disagreement and 10 complete agreement. Statements with a score ≥ 8 by ≥ 80% of panelists achieved the group consensus. In case of a score < 8, participants were invited to express their reasonings and propose an alternative statement supported by the articles in the SMART library or on their personal experience by using the option for free comments.

A maximum of three rounds of Delphi was planned. After each round, the task group of authors developed a new questionnaire for the next round including the questions which failed the consensus, after modifying the statements and the discussions and adding new references according to the feedback from the participants. For the items with no ade

Stage 4 (analysis of the results and development of the template): All information collected during the course of the research was kept strictly confidential, and results were only traceable and accessible to the task group of authors. The task group analyzed the data and developed the template accordingly. The results of the SMART project were su

No complex statistical methods were needed for this study. The standard for Delphi consensus has not been well established in the literature. The number of panelists is determined by the mode of data collection, the level of panel heterogeneity, and how panelists interact. Online panels allow for expanding the type and number of panelists[21]. Lar

The collaborative group consisted of 95 experts from 31 countries (Table 1, Supplementary material), including 69 co

| Characteristics | |

| Gender, n (%) | Males: 24 (25.3) |

| Females: 71 (74.7) | |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 49.7 ± 10.5 |

| Region, n (%) | Europe: 63 (66.3); Asia: 20 (21.0); North America: 4 (4.2); South America: 3 (3.1); Africa: 3 (3.1); Australia: 2 (2.1) |

| Scientific societies | Asian Pacific Federation of Coloproctology, Emirates Society of Colon and Rectal Surgery, European Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology, European Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine and Biology, European Society of Colo-Proctology, French National Society of Coloproctology, International Society of Coloproctology, International Society of Treatment of Anorectal Disorders, Italian Society of Medical and Interventional Radiology Foundation, Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery, Polish Club of Coloproctology |

| Type of hospital, n (%) | Academic/university: 64 (67.3) |

| Public regional: 12 (12.6) | |

| Private: 16 (16.8) | |

| Other: 3 (3.1) | |

| Duration of medical practice, mean ± SD, yr | 20.0 ± 10.7 |

| Specialty, n (%) | Colorectal surgeons: 69 (72.6) |

| Radiologists: 23 (24.2) | |

| Anatomists: 2 (2.1) | |

| Gastroenterologists: 1 (1) | |

| No. of EAUS/MRI assessment for anal fistulas, n (%) | 10/mo: 23 (24.2); 10–20/mo: 31 (32.6); 20–30/mo: 15 (15.8) |

| > 30/mo: 23 (24.2); Not applicable: 3 (3.1) |

Stage 1 (January–February 2023): The systematic review of the literature revealed a heterogeneous spread of scientific evidence. In total, 119 research papers were included in the SMART library. On February 26, 2023, at the online launch meeting, the task group of authors, the panelists, and the international scientific societies endorsing the study were introduced. Each item of the existing templates[1,2,5-9] was analyzed and discussed in terms of possible modifications.

Stage 2 (March 2023): On March 28, 2023, during the second online meeting, the final version of the digital SMART library, including an additional 32 references proposed by the panelists (total number: 151 articles; https://www.dropbox.com/sh/thre93x5m7pht85/AAD5BMBSvoubR1ekACcnB_mZa?dl=0), was presented. The preliminary questionnaire for the Delphi, based on the selection process from the literature, was discussed.

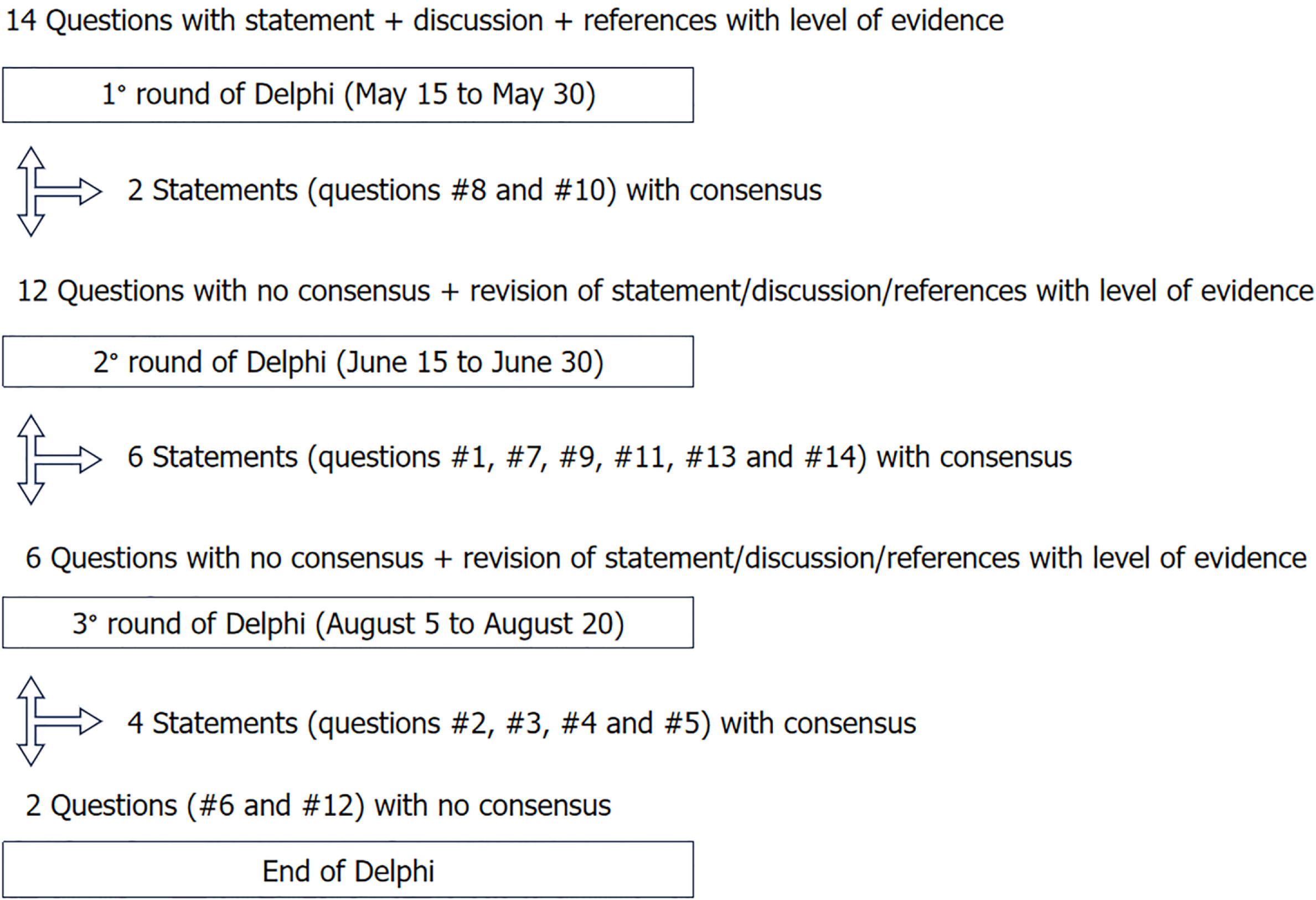

Stage 3 (April–August 2023): On April 29, 2023, at the third online meeting, the final list of 14 questions (Table 2) for the first Delphi survey was presented. After three rounds, the overall consensus was 85.7% (12 of 14 questions) (Table 3, Figure 1). Two statements achieved immediate consensus. The remaining 12 statements were redrafted, following input from the panelists, to be voted on again. Six statements achieved group consensus during the second round, and four statements during the third round of voting. Two statements did not gain consensus and were not included in the SMART template.

| Questionnaire | |

| Question #1 | Is the Park’s classification optimal to be reported by MRI/EAUS for the characterization of the primary tract? |

| Question #2 | Should the Park’s classification be modified or supplemented? |

| Question #3 | Is the location of the primary tract on a clock dial optimal to be reported by MRI/EAUS, or should it be modified? |

| Question #4 | Is the height of the primary tract properly described (≤ 30% and > 30%)? |

| Question #5 | Is the inclusion of the diameter of the fistula in the template correct or should be modified? |

| Question #6 | Should a fistula tract angle be added to the template? |

| Question #7 | Are secondary tracts precisely defined: Number, location, and type? |

| Question #8 | Are internal opening items, such as number, location on a clock dial, and patency complete or require completion? |

| Question #9 | Is information on associated abscess, such as location according to the Corman classification, accurate? |

| Question #10 | Is it sufficient to report sphincter integrity, location of damage, and percentage of sphincter involved? |

| Question #11 | Is the graphic presentation of the fistula included in a template appropriate or it should be modified? |

| Question #12 | Should a video describing the fistula details (if permitted by the rules) supplement the template of the fistula? |

| Question #13 | Does the template include all the most relevant findings for the treatment decisions or other additional elements of the fistula should be included in the template? |

| Question #14 | The following definitions are relevant for examiners describing anal fistulas by MRI and EAUS. Do you accept them in their current form, or do they require modification or addition? In the latter case, please suggest a correction |

| Statement | Percentage of agreement | Median (IQR) of answers | No. of round in which agreement was achieved |

| #1 | 89.5 | 10 (9-10) | 2 |

| #2 | 81.0 | 10 (8-10) | 3 |

| #3 | 93.7 | 10 (10-10) | 3 |

| #4 | 91.5 | 10 (9-10) | 3 |

| #5 | 80.0 | 10 (8-10) | 3 |

| #6 | 75.8 | 9 (8-10) | No consensus |

| #7 | 97.9 | 10 (9-10) | 2 |

| #8 | 95.8 | 10 (10-10) | 1 |

| #9 | 96.8 | 10 (9-10) | 2 |

| #10 | 95.8 | 10 (10-10) | 1 |

| #11 | 94.7 | 10 (9-10) | 2 |

| #12 | 66.3 | 10 (7-10) | No consensus |

| #13 | 96.81 | - | 2 |

| #14 | 87.41 | - | 2 |

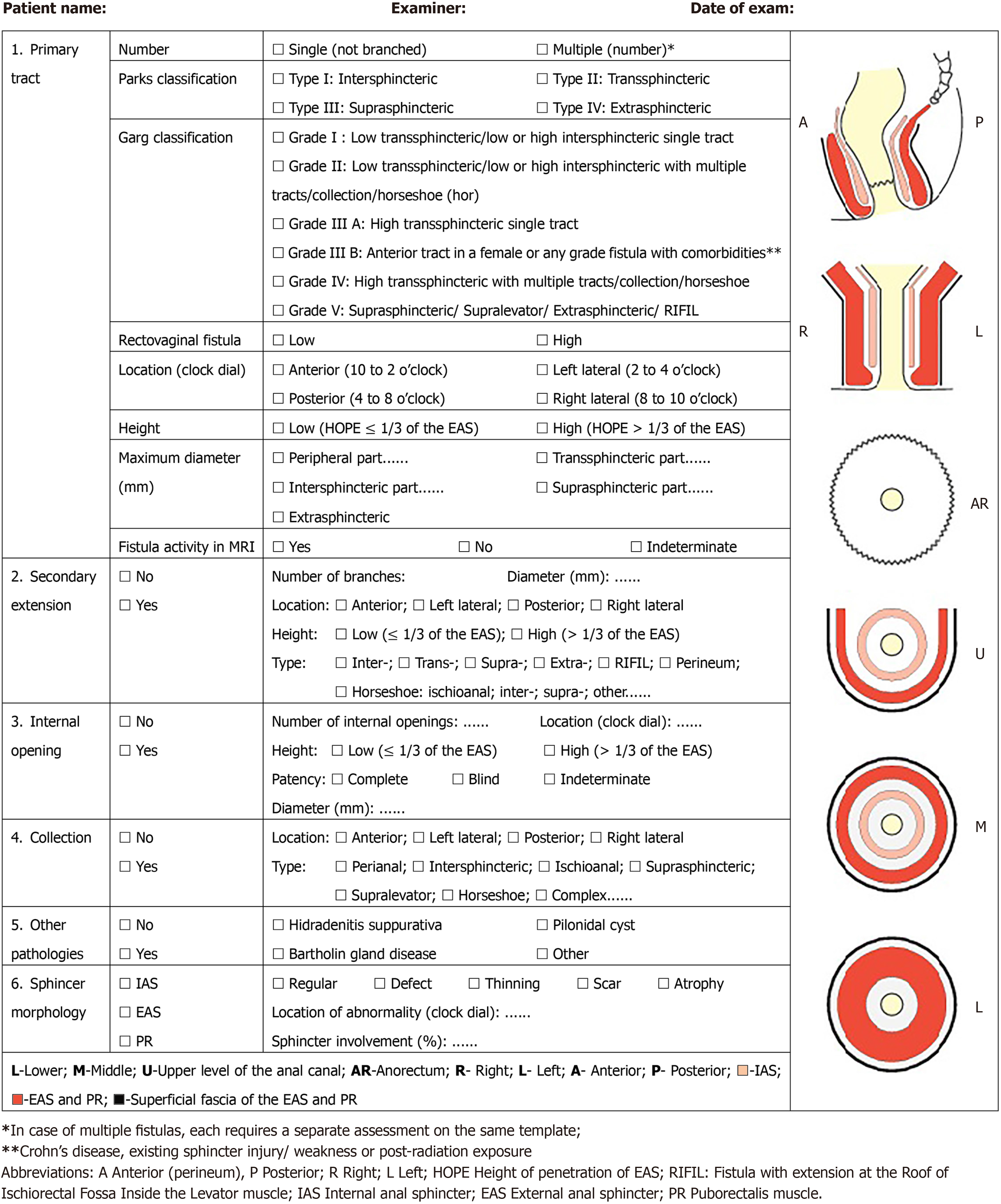

Stage 4 (September–December 2023): All collaborators completed the three rounds. Verification of the questionnaires confirmed that there were no missing data. Results were analyzed, and the SMART, consisting of six clinically relevant features for anal fistula management, was developed (Figure 2). The SMART will be accessible at: http://jultrason.pl/assets/pdf/SmartTemplate.pdf.

Question #1. Is the Parks classification optimal to be reported by MRI/EAUS for the characterization of the primary tract? After two rounds, panelists (89.5%) recommended reporting the total number of tracts (single vs multiple) along with the Parks classification[22] for any fistula identified (LE 5)[1]. Rectovaginal fistulas (high or low) should also be described.

Question #2. Should the Parks classification be modified or supplemented? In the first round of the Delphi, panelists identified limitations and shortcomings in the Parks classification (Table 4). In the second round, it was asked if other classifications[11,12] could be considered (Tables 4 and 5). In the third round, consensus was reached (81% of panelists) to include in the template the Garg classification[11,12] along with the Parks classification. This classification validated by data on a large sample size (LE 2) allows to accurately grade the severity of the fistula[12].

| Shortcomings in the Parks classification | |

| 1 | The Parks classification does not categorize fistulas based on the increasing severity[22]. Transsphincteric fistulas are considered more complex than intersphincteric fistulas. However, a low linear transsphincteric fistula involving ≤ 30% of the external sphincter (Parks grade II) is simpler than a high intersphincteric horseshoe fistula with a high rectal opening (Parks grade I). Therefore, the classification does not grade fistulas according to the complexity |

| 2 | The Parks classification does not provide any recommendations for the management of fistulas. |

| 3 | The Parks classification was not validated by MRI/EAUS as these investigations were not available at the time of its introduction[22]. The 25% of suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric fistulas in the original cohort is not consistent with the literature and it could be due to the absence of preoperative imaging[22] |

| 4 | Parks grade IV is assigned to the extrasphincteric fistulas. However, by using MRI/EAUS, it has been shown that extrasphincteric fistulas are extremely rare[3,4] |

| 5 | The Parks classification does not consider many characteristics of the fistula such as the presence of an abscess, horseshoe extension, anterior location in a female or patients comorbidities like Crohn’s disease, previous irradiation, weakened sphincter due to previous operations or obstetrical anal sphincter injury[22] |

| Parks classification[22] | Garg classification[11,12] | St. James University Hospital classification[36] | |

| Grade I | Intersphincteric | Low trans-sphincteric/low or high intersphincteric: Single tract | Intersphincteric linear |

| Grade II | Transsphincteric | Low trans-sphincteric/low or high intersphincteric: Multiple tracts, horseshoe or associated abscess | Intersphincteric with extension/s or associated abscess |

| Grade III | Suprasphincteric | IIIA: High trans-sphincteric: Single tract; IIIB: (1) Anterior fistula in a female or any lower; (2) Grade I or II fistula with associated comorbidities1 | Trans-sphincteric linear |

| Grade IV | Extrasphincteric | High trans-sphincteric: Multiple tracts, horseshoe or associated abscess | Trans-sphincteric with extension/s or associated abscess |

| Grade V | Suprasphincteric or supralevator or extrasphincteric or RIFIL fistula | Supralevator and translevator extension |

Question #3. Is the location of the primary tract on a clock dial optimal to be reported by MRI/EAUS, or should it be modified? The location of the tract on a clock dial is widely accepted, however, the position of the patient during the exam can generate confusion. Consensus was reached (93.7% in the third round) to report the location as anterior (10 to 2 o’clock), left lateral (2 to 4), posterior (4 to 8) and right lateral (8 to 10), irrespective of the patient’s position (LoE 5).

Question #4. Is the height of the primary tract properly described (≤ 30% and > 30% of external anal sphincter)? Fistula height is the primary determinant of surgical treatment[9]; however it is still debated how to measure the height of the tract on MRI/EAUS. In the third round of Delphi, panelists (91.5%) agreed to report the height of penetration of the external anal sphincter (HOPE)[9]. Low fistulas involve ≤ 1/3, and high fistulas > 1/3 of the external anal sphincter (LE 3).

Question #5. Is the inclusion of the diameter of the fistula in the template correct? The panelists agreed to report the diameter of the fistula because it can influence the choice of surgical treatment. After the third round, consensus (80.0% of panelists) was reached to measure the maximum diameter of the tract in the different parts of the fistula, depending on the type (LE 5).

Question #6. Should a fistula tract angle be added to the template? After three rounds, no consensus was obtained (grade of agreement 75.8%) to include the tract angle[23] in the template (LE 5).

Question #7. Are secondary tracts precisely defined: number, location, and type? After two rounds, there was con

Question #8. Are internal opening items (number, location on a clock dial, and patency) complete or require com

Question #9. Is information on associated abscesses, such as location according to the Corman classification, accurate? Reporting of location, type, and dimension of anal collections is mandatory. After two rounds of Delphi, panelists (96.8%) agreed there is no need to use the Corman classification[14] of perianal abscesses as they can be classified similarly to anal fistulas (LE 5). The group recommended using the term collection instead of abscess and provide its localization and type.

Question #10. Is it sufficient to report sphincter integrity, location of damage and percentage of sphincter involved? After one round, a consensus (95.8% of panelists) was found to report any sphincter abnormality resulting from previous injury (obstetrical or surgical) or age-related atrophy (LE 3)[25].

Question #11. Should a graphic representation of the fistula be included in the template? In the second round of the Delphi, panelists (94.7%) agreed to include the three-plane and the three-level schematic diagrams of the anal canal to allow the examiner to draw the fistula pathway (LE 5).

Question #12. Should a video of the fistula imaging supplement the template? The panelists did not reach a consensus (grade of agreement 66.3%) to add a video to supplement the report (LE 5).

Question #13. Does the template include all the most relevant findings for treatment decisions or other additional elements of the fistula should be added? According to the panelists (96.8% after 2 rounds), the SMART includes the six clinically relevant features relevant for treatment decisions (LE 5) (Figure 2).

Question #14. The following definitions are relevant for examiners describing anal fistulas by MRI and EAUS. Do you accept them in their current form or do they require modification or addition? After two rounds, consensus (87.4% of panelists) was reached on the definitions of anal fistulas reported in Table 6 (LE 5).

| Terms | Definitions |

| Primary fistula | Main fistulous tract with the internal opening at the dentate line (occasionally the internal opening can be lower or higher than the dentate line) |

| Single fistula | Fistula without branching (extensions/ramifications) |

| Multiple fistulas | More than one primary fistula with their corresponding internal openings |

| Branching fistula | Fistula with branches (extensions/ramifications) |

| Low fistula[12,25] | Fistula that involves ≤ 1/3 of the external anal sphincter |

| High fistula[12,25] | Fistula that involves > 1/3 of the external anal sphincter |

| Simple fistula[12,25] | Low intersphincteric or low transsphincteric primary fistula (Garg grades I/II)[11,12] at low risk of incontinence or recurrence |

| Complex fistula[12,25] | High inter- or trans-sphincteric, suprasphincteric, extrasphincteric fistula (Garg grades III–V)[11,12], ano/rectovaginal fistula, any fistula in Crohn’s disease, a fistula postradiotherapy, anterior fistula in a female, recurrent fistula, fistulas with multiple tracts, pre-existing sphincter injuries at high risk of postoperative incontinence or recurrence |

This international, collaborative, Delphi consensus was conducted to develop a structured template (SMART) to stan

The SMART study overcame the limitations of other consensus studies (Table 7). The template developed by Ho et al[6] is not evidence-based, and being from a single institution is not transferable to the scientific community at large. ESGAR used a monodisciplinary approach for the consensus statement since the target audience for this guideline were radio

| Ref. | Approach | Imaging modalities | Institutions | Methodology | N | Evidence-based |

| Tuncyurek et al[7], 2019 | Multidisciplinary (RAD & CRS) | MRI | Single center | Institutional meeting | 3 | No |

| Ho et al[6], 2019 | Multidisciplinary (RAD & CRS) | MRI | Single center | Institutional meeting | ns | No |

| Halligan et al[8], 2020 | Monodisciplinary (RAD) | MRI, CT, EAUS | Multicenter | Delphi process | 13 | Yes (139 articles) |

| Sudoł-Szopińska et al[1], 2021 | Multidisciplinary (RAD & CRS) | MRI | Multicenter | Online survey | 5 | No |

| Garg et al[9], 2022 | Multidisciplinary (RAD & CRS) | MRI | Single center | Institutional meeting | 4 | No |

| Iqbal et al[5], 2022 | Multidisciplinary (RAD, GASTR, CRS) | MRI | Multicenter | Online survey | 14 | Yes (26 articles) |

| SMART, 2024 (current paper) | Multidisciplinary (RAD, GASTR, CRS, ANAT) | MRI, EAUS | Multicenter | Delphi process | 95 | Yes (151 articles) |

Although the SMART collaborators confirmed the importance of using the Parks classification[22], they identified several shortcomings (Table 4)[11]. For this reason, the group proposed to incorporate the Garg classification[12] in the template, which is based on the height of the fistula and on the amount of anal sphincter complex involved (Table 5). The criteria for considering anal fistulas as high or low if involving more or less than 30% of the external anal sphincter have also been recommended by the guidelines of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons as a factor relevant for surgical decision-making[12,14,26] (Table 5). Unlike previous classifications, the Garg classification guides disease mana

MRI and 3D-EAUS are both able to define the new item HOPE (height of penetration of the external anal sphincter by the fistula tract)[2,3,9,24], and this parameter was included by the panelists in the template. Usually, radiologists report the location of the IO, but that does not convey the amount of involvement of the external anal sphincter, as the level of the IO and the amount of external anal sphincter involved can vary significantly[9]. The latter is of paramount importance to the operating surgeon as the damage to external anal sphincter needs to be minimized to maintain continence. The

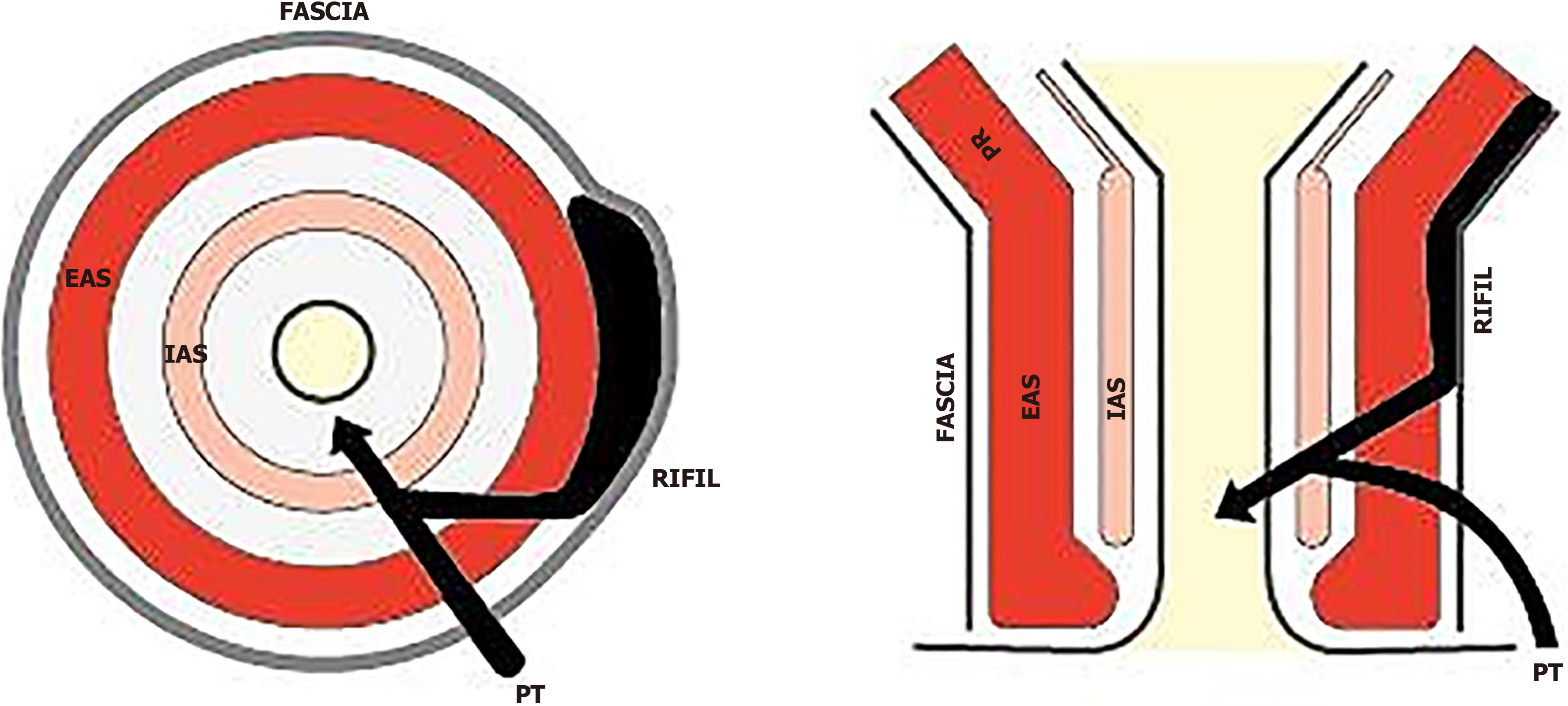

Another item that the panelists considered important to include was the maximum diameter of the fistula because it can influence the choice of surgical procedures such as: ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT)[15,27-29], the transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS)[16-18,30,31], video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT)[32], stem cell[33,34] or fistula laser closure[35]. This is consistent with Iqbal et al[5] recommendation and ESGAR consensus[8]. Other characteristics of the anal fistulas included in the template were number, height, and location of any secondary tracts. Consensus was reached to include in the SMART the new parameter of RIFIL[10]. RIFIL fistulas or extensions are present at the roof of the ischiorectal fossa inside the levator muscle. Failure to identify RIFIL tracts can lead to mismanagement, a higher recurrence rate, and an enhanced risk of damage to the external anal sphincter and the levator ani muscle[10].

MRI and EAUS are accurate and reliable in assessing the number, location, diameter, and height of the IO[8,9,24,36]. The SMART collaborators recommended reporting the patency of the IO, which can be suspected by inflammation on MRI[37] or using the Cho criteria[24] or the hydrogen peroxide injection through the external orifice on EAUS[37]. A wrong diag

The need to preserve anal continence is higher than the risk of postoperative fistula recurrence. Surprisingly, Tunc

A graphic presentation (St. Mark’s Hospital fistula operations sheet) was initially proposed by Gaertner et al[14]. Ho et al[6] published a modified diagrammatic worksheet to include the height of the IO, previous sphincter injury, and fistula activity. Sudoł-Szopińska et al[1] introduced the St. Elizabeth template for MRI fistula reporting with a scheme to draw the fistula characteristics. The SMART collaborative group underlined the importance of adding in the template the scheme of the anal canal for fistula drawing.

The current study has some limitations. The first is inherent to the Delphi process and to the risk that marginal opinions may impact the final consensus statements. To prevent bias, a large number of collaborators were included in the panel to ensure that the process was based on broad consensus. Moreover, the provenience of the experts from 94 centers in 31 countries contributes to the generalizability of the SMART across the international medical communities. Second, the prevalence of colorectal surgeons over radiologists (72.6% vs 24.2%) may potentially bias the perspective of surgeons against the perspective of radiologists. However, the dual role of the colorectal surgeons being both sonogra

This large, international collaborative Delphi study developed a structured SMART template for reporting of anal fistulas on EAUS and MRI. The SMART does not replace the text report but is an additional tool that can be used in clinical practice to standardize imaging findings in a simple, systematic, time-efficient visual diagram, useful to the referring physicians as a practical roadmap for the management. Future reliability and reproducibility studies are needed to va

The authors thank all collaborators in the SMART Group who were involved in the Delphi process for their efforts and contribution to this large, international collaborative study. The authors also thank Małgorzata Mańczak, Department of Gerontology, Public Health and Didactics, National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Warsaw, Poland for her contribution to the statistical analysis.

SMART Collaborative Group: Felix Aigner, Mohammed Alharbi, Peter Ambe, Erman Aytac, Kaushik Bhattacharya, Gabriele Bislenghi, Stéphanie Breukink, Antonio Brillantino, Steven Brown, Shantikumar Chivate, Przemysław Ciesielski, Bogdan Ciszek, Hugo Cuellar-Gomez, Luis Curvo Semedo, Sushil Dawka, Vincent de Parades, Hossam Elfeki, Nadia Fathallah, Linda Ferrari, Barbara Frittoli, Frank Frizelle, Gaetano Gallo, Ashish Ganatra, Damian Garcia Olmo, Pankaj Garg, Valentina Giaccaglia, Pasquale Giordano, Lester Gottesman, Kevin Göttgens, Ugo Grossi, Baris Gulcu, Pankaj Gupta, Alison Hainsworth, Mohamed Amine Haouari, Mukesh Harisinghani, Art Hiranyakas, Anna Hołdakowska, Daniela Husarik, Francesca Iacobellis, Franco Iafrate, Evani Jain, Sachin Jamma, Christian Jenssen, Rosa M Jimenez Rodriguez, David Kachlik, Damir Karlovic, Baljit Kaur, Małgorzata Kołodziejczak, Dorian Krsul, Giulio Lombardi, Gaetano Luglio, Christian Magbojos, Lukas Marti, Anders Mellgren, Monica Millan, Hermogeneous Monroy, Sthela Maria Murad-Regadas, Michał Nieciecki, Andreas Nordholm-Carstensen, Joseph Nunoo-Mensah, Lucia Oliveira, Jacek Piłat, Vittorio Piloni, Joanna Podgórska, Monika Popiel, Carlo Ratto, Alfonso Reginelli, Arun Rojanasakul, Luigia Romano, April Roslani, Manuel Roxas, Narimantas Evaldas Samalavicius, Tarik Sammour, Giulio Aniello Santoro, Daria Schettini, Alexis Schizas, Sabine Schmidt Kobbe, Francis Seow Choen, Mostafa Shalaby, Navjeet Singh, Kaspars Snippe, Antonino Spinelli, Scott R. Steele, Jasper Stijns, Luca Stoppino, Alessandro Sturiale, Iwona Sudoł-Szopińska, Phil Tozer, Charles Tsang, Fiek Van Tilborg, Steve Ward, Anna Wiączek, Vipul D Yagnik, Marko Zelic, David D.E. Zimmerman, Roberto Zinicola.

| 1. | Sudoł-Szopińska I, Santoro GA, Kołodziejczak M, Wiaczek A, Grossi U. Magnetic resonance imaging template to standardize reporting of anal fistulas. Tech Coloproctol. 2021;25:333-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sudoł-Szopińska I, Kołodziejczak M, Aniello GS. A novel template for anorectal fistula reporting in anal endosonography and MRI - a practical concept. Med Ultrason. 2019;21:483-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brillantino A, Iacobellis F, Reginelli A, Monaco L, Sodano B, Tufano G, Tufano A, Maglio M, De Palma M, Di Martino N, Renzi A, Grassi R. Preoperative assessment of simple and complex anorectal fistulas: Tridimensional endoanal ultrasound? Radiol Med. 2019;124:339-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Varsamis N, Kosmidis C, Chatzimavroudis G, Apostolidou Kiouti F, Efthymiadis C, Lalas V, Mystakidou CM, Sevva C, Papadopoulos K, Anthimidis G, Koulouris C, Karakousis AV, Sapalidis K, Kesisoglou I. Preoperative Assessment of Perianal Fistulas with Combined Magnetic Resonance and Tridimensional Endoanal Ultrasound: A Prospective Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Iqbal N, Sackitey C, Gupta A, Tolan D, Plumb A, Godfrey E, Grierson C, Williams A, Brown S, Maxwell-Armstrong C, Anderson I, Selinger C, Lobo A, Hart A, Tozer P, Lung P. The development of a minimum dataset for MRI reporting of anorectal fistula: a multi-disciplinary, expert consensus process. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:8306-8316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ho E, Rickard MJFX, Suen M, Keshava A, Kwik C, Ong YY, Yang J. Perianal sepsis: surgical perspective and practical MRI reporting for radiologists. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:1744-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tuncyurek O, Garces-Descovich A, Jaramillo-Cardoso A, Durán EE, Cataldo TE, Poylin VY, Gómez SF, Cabrera AM, Hegazi T, Beker K, Mortele KJ. Structured versus narrative reporting of pelvic MRI in perianal fistulizing disease: impact on clarity, completeness, and surgical planning. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:811-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Halligan S, Tolan D, Amitai MM, Hoeffel C, Kim SH, Maccioni F, Morrin MM, Mortele KJ, Rafaelsen SR, Rimola J, Schmidt S, Stoker J, Yang J. ESGAR consensus statement on the imaging of fistula-in-ano and other causes of anal sepsis. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:4734-4740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Garg P, Kaur B, Yagnik VD, Dawka S. Including video and novel parameter-height of penetration of external anal sphincter-in magnetic resonance imaging reporting of anal fistula. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:271-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Garg P, Dawka S, Yagnik VD, Kaur B, Menon GR. Anal fistula at roof of ischiorectal fossa inside levator-ani muscle (RIFIL): a new highly complex anal fistula diagnosed on MRI. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:5550-5563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Garg P. Comparing existing classifications of fistula-in-ano in 440 operated patients: Is it time for a new classification? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Surg. 2017;42:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garg P. Assessing validity of existing fistula-in-ano classifications in a cohort of 848 operated and MRI-assessed anal fistula patients - Cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;59:122-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Emile SH, Elfeki H, El-Said M, Khafagy W, Shalaby M. Modification of Parks Classification of Cryptoglandular Anal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:446-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gaertner WB, Burgess PL, Davids JS, Lightner AL, Shogan BD, Sun MY, Steele SR, Paquette IM, Feingold DL; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:964-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fogle SE, Donahue CA, Beresneva O, Kuhnen AH, Kleiman DA, Breen EM, Schoetz DJ Jr, Roberts PL, Marcello PW, Saraidaridis JT. Horseshoe Fistulae in the Age of LIFT. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26:1077-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang C, Huang T, Wang X. Efficacy and safety of transanal opening of intersphincteric space in the treatment of high complex anal fistula: A metaanalysis. Exp Ther Med. 2024;28:306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li YB, Chen JH, Wang MD, Fu J, Zhou BC, Li DG, Zeng HQ, Pang LM. Transanal Opening of Intersphincteric Space for Fistula-in-Ano. Am Surg. 2022;88:1131-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Huang B, Wang X, Zhou D, Chen S, Li B, Wang Y, Tai J. Treating highly complex anal fistula with a new method of combined intraoperative endoanal ultrasonography (IOEAUS) and transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS). Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2021;16:697-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Plumb AAO, Lambregts D, Bellini D, Stoker J, Taylor S; ESGAR Research Committee. Making useful clinical guidelines: the ESGAR perspective. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:3757-3760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, Wales PW. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2265] [Cited by in RCA: 1824] [Article Influence: 165.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi Technique in Health Sciences: A Map. Front Public Health. 2020;8:457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 508] [Article Influence: 101.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg. 1976;63:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1072] [Cited by in RCA: 928] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zinicola R, Cracco N, Del Rio P, Bresciani P. The angle of the anal fistula track and the distance between the internal opening and the anorectal junction: two further useful parameters in MRI? Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:323-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cho DY. Endosonographic criteria for an internal opening of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:515-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Santoro GA, Abbas MA. Complex anorectal fistulas. In: Steele SR, Hull TL, Read TE, Saclarides TJ, Senagore AJ, Whitlow CB. The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery 2016. Third Edition. Berlin: Springer, 2016: 245-274. |

| 26. | Steele SR, Kumar R, Feingold DL, Rafferty JL, Buie WD; Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the management of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1465-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hong KD, Kang S, Kalaskar S, Wexner SD. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) to treat anal fistula: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:685-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Awad PBA, Hassan BHA, Awad KBA, Elkomos BE, Nada MAM. A comparative study between high ligation of the inter-sphincteric fistula tract via lateral Approach Versus Fistulotomy and primary sphincteroplasty in High Trans-Sphincteric Fistula-in-Ano: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Surg. 2023;23:224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jayne DG, Scholefield J, Tolan D, Gray R, Senapati A, Hulme CT, Sutton AJ, Handley K, Hewitt CA, Kaur M, Magill L; FIAT Trial Collaborative Group. A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Safety, Efficacy, and Cost-effectiveness of the Surgisis Anal Fistula Plug Versus Surgeon's Preference for Transsphincteric Fistula-in-Ano: The FIAT Trial. Ann Surg. 2021;273:433-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Huang H, Ji L, Gu Y, Li Y, Xu S. Efficacy and Safety of Sphincter-Preserving Surgery in the Treatment of Complex Anal Fistula: A Network Meta-Analysis. Front Surg. 2022;9:825166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mishra S, Thakur DS, Somashekar U, Verma A, Sharma D. The management of complex fistula in ano by transanal opening of the intersphincteric space (TROPIS): short-term results. Ann Coloproctol. 2023;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tian Z, Li YL, Nan SJ, Xiu WC, Wang YQ. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment for complex anorectal fistulas in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:783-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang Y, Rao Q, Ma Y, Li X. Platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of anal fistula: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023;38:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | An Y, Gao J, Xu J, Qi W, Wang L, Tian M. Efficacy and safety of 13 surgical techniques for the treatment of complex anal fistula, non-Crohn CAF: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024;110:441-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Giamundo P, De Angelis M. Treatment of anal fistula with FiLaC(®): results of a 10-year experience with 175 patients. Tech Coloproctol. 2021;25:941-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Brillantino A, Iacobellis F, Brusciano L, Giordano P, Santoro GA, Sudol-Szopinska I, Grillo M, Maglio MN, Foroni F, Palumbo A, Menna MP, Antropoli C, Docimo L, Renzi A. Impact of Preoperative Three-Dimensional Endoanal Ultrasound on the Surgical Outcome of Primary Fistula in Ano. A Multi-Center Observational Study of 253 Patients. Surg Innov. 2023;30:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | West RL, Zimmerman DD, Dwarkasing S, Hussain SM, Hop WC, Schouten WR, Kuipers EJ, Felt-Bersma RJ. Prospective comparison of hydrogen peroxide-enhanced three-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography and endoanal magnetic resonance imaging of perianal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1407-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kucharzik T, Tielbeek J, Carter D, Taylor SA, Tolan D, Wilkens R, Bryant RV, Hoeffel C, De Kock I, Maaser C, Maconi G, Novak K, Rafaelsen SR, Scharitzer M, Spinelli A, Rimola J. ECCO-ESGAR Topical Review on Optimizing Reporting for Cross-Sectional Imaging in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:523-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA, Stoker J, Khanna R, Ng SC, Panés J, van Assche G, Liu Z, Hart A, Levesque BG, D'Haens G; World Gastroenterology Organization, International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases IOIBD, European Society of Coloproctology and Robarts Clinical Trials; World Gastroenterology Organization International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases IOIBD European Society of Coloproctology and Robarts Clinical Trials. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut. 2014;63:1381-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kołodziejczak M, Santoro GA, Obcowska A, Lorenc Z, Mańczak M, Sudoł-Szopińska I. Three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound is accurate and reproducible in determining type and height of anal fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Morris J, Spencer JA, Ambrose NS. MR imaging classification of perianal fistulas and its implications for patient management. Radiographics. 2000;20:623-35; discussion 635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |