Published online Oct 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3114

Revised: July 25, 2024

Accepted: September 3, 2024

Published online: October 27, 2024

Processing time: 110 Days and 10.8 Hours

Total mesorectal excision remains the gold standard for the management of rectal cancer however local excision of early rectal cancer is gaining popularity due to lower morbidity and higher acceptance by the elderly and frail patients.

To investigate the results of local excision of rectal cancer by transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS) approach carried out at three large cancer centers in the United Kingdom.

TEMS database was retrospectively reviewed to assess demographics, operative findings and post operative clinical and oncological outcomes. This is a retro

Two hundred and twenty-two patients underwent TEMS surgery. This included 144 males (64.9%) and 78 females (35.1%), Median age was 71 years. The median distance of the tumours from the anal verge 4.5 cm. Median tumour size was 2.6 cm. The most frequent operative position of the patient was lithotomy (32.3%), Full-thickness rectal wall excision was done in 204 patients. Median operating time was 90 minutes. Average blood loss was minimal. There were two 90-day mortalities. Complete excision of the tumour with free microscopic margins by > 1mm were accomplished in 171 patients (76.7%). Salvage total mesorectal excision was performed in 42 patients (19.8%). Median disease-free survival was 65 months (range: 3-146 months) (82.8%), and median overall survival was 59 months (0-146 months).

TEMS provides a promising option for early rectal cancers (Large adenomas-cT1/cT2N0), and selected therapy-responding cancers. Full-thickness complete excision of the tumour is mandatory to avoid jeopardising the oncological outcomes.

Core Tip: In this multi-centre study, Trans-anal endoscopic microsurgery was employed in 222 patients of early rectal cancers (T1-T2/early T3, N0), with acceptable oncologic outcomes and morbidity. The main independent factor of survival was the completeness of local excision, while completion total mesorectal excision did not offer a survival benefit. The limitations of this study were the heterogenicity of the data, its retrospective analysis, and the non-comparative design to the total mesorectal excision, which is the standard of care. However, this rectum preservation strategy can be a substitute in selected patients, especially in the evolving era of precision medicine.

- Citation: Farid A, Tutton M, Thambi P, Gill T, Khan J. Local excision of early rectal cancer: A multi-centre experience of transanal endoscopic microsurgery from the United Kingdom. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(10): 3114-3122

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i10/3114.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i10.3114

Despite the multidisciplinary advances in the management of rectal cancer, proctectomy with total mesorectal excision (TME) remains the standard of surgical care for the majority of patients, since its description by Heald et al[1], and is associated with reduced 5-year local recurrence rates to less than 10%[1-3]. Local excision of rectal cancer by trans-anal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS), developed by Buess et al[4], attempted at removing an intact non-fragmented specimen, hence enabling a better histopathological assessment of the resected cancer. Although first described in 1980, TEMS did not attract global interest until 2009, after significant developments in surgical optics and endoscopic instrumentations, resulting in evolution of TEMS.

Morbidity of TME surgery and studies demonstrating favourable outcomes of TEMS in selected early rectal cancers (T1)[5-9] encouraged introducing this technique in selected early rectal cancer (National comprehensive cancer network guidelines)[10]. National comprehensive cancer network placed precise selection criteria for tumours candidate for local excision, which includes; T1-sm1 tumour, N0, less than 3 cm, less than one third of circumference, clear margins 3 mm at least, low or moderate grade, no lympho-vascular invasion nor perineural invasion, cancer in polyp, or indeterminate pathology.

Studies implemented this technique in more advanced tumors (T2 and selected T3) in addition to neoadjuvant/adjuvant radiotherapy, reporting comparable oncological outcomes with better quality of life, with avoidance of the associated complications of radical surgery, especially genito-urinary dysfunction and stoma formation[11-13].

The application of TEMS as a standard therapy for rectal cancer is hindered by its questionable oncological safety, the inability to address the mesorectal basin with its possible tumoral involvement, and limited level 1 data. Hence while opting TEMS resection of rectal cancer a careful discussion needs to happen balancing the risk of lymph node metastasis, local recurrence and distant metastasis vs morbidity and mortality.

TEMS for early rectal cancer may be an attractive option, especially in the elderly patients. However regular surveillance is mandatory to pick up an early recurrence and offer a salvage option. Data should be carefully monitored and patients’ outcomes recorded in a prospective database. This study aimed to analyze a multicentric database for prospective case series of TEMS carried out for early rectal cancer within the United Kingdom.

This is a multi-centre experience of TEMS in the management of selected cases of rectal tumours, carried out between May 2008 to May 2020 at three NHS hospitals across the United Kingdom (Portsmouth Hospitals University NHS Trust, East Suffolk and North Essex NHS Trust, and North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Trust). This is a retrospective review of the prospective databases, which included all patients operated with TEMS approach, for early rectal cancer (Node-negative T1-T2), selected T3 in unfit/frail patients.

Patients with rectal cancers were locally evaluated pre-operatively by a diffusion-weighed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), endorectal ultrasound and chest and abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) with contrast. Patients received neoadjuvant short course radiotherapy if > T1 and were re-evaluated to monitor tumour response.

The management of each patient was discussed at the colorectal multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT). Patients were provided an informed consent about potential benefits and drawbacks of TEMS approach. Mechanical bowel preparation was given with two sachets of Picolax. Preoperative anaesthetic assessment was carried out in high-risk cases. All patients were operated under general anaesthetic.

TEMS was carried out using Richard-Wolff TEMS (Richard Wolf GmbH) platform under general anaesthetic. Patient positioning on the operating table was determined by the location of the cancer. For anteriorly based tumours patient was placed prone on the operating table. While in the case of posteriorly based tumours lithotomy or Lloyd-Davis position was used and for lateral tumours, the patient was placed either lateral or lithotomy.

A full thickness excision was carried out followed by saline washout and primary closure of the rectal defect. Five days of post-operative antibiotics were given along with analgesics and laxatives.

Patients were managed post operatively in an enhanced recovery program and were discharged home as soon as pain free and mobilising. The histology was discussed at the colorectal MDT for follow-up, adjuvant treatment or the need of salvage TME. The standard follow up involved MRI, flexible sigmoidoscopy and clinical examination every 3 months for the first two years, then every 6 month for the next two years and then annually till year 5.

Data were analyzed using International Business Machines (IBM) statistical product and service solutions (SPSS) corporation (Released 2019. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY, United States). Qualitative data were described using number and percentage. Quantitative data were described using median (minimum and maximum) for non-parametric data and mean, SD for parametric data after testing normality using Kolmogrov-Smirnov test. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the (0.05) level. Kaplan-Meier test was used to calculate overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) with using log rank χ2 to detect effect of risk factors affecting survival.

Two hundred and twenty-two patients underwent TEMS surgery (Table 1). This included 144 males (64.9%) and 78 females (35.1%). Median age was 71 years (range: 41-90), which may reflect this subset of patients with older age group who may benefit from such less extensive surgery.

| Characteristics | |

| Number of cases | 222 |

| Age (median)/years | 71 (41-90) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 144 (64.9) |

| Female | 78 (35.1) |

| Distance from AV (median)/cm | 4.5 (0.5-30) |

| Tumor size (median)/mm | 26 (1-140) |

| Preoperative pathology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 201 (90.5) |

| Post RT cCR | 3 (1.35) |

| Adenoma | 16 (7.2) |

| Local recurrence | 1 (0.45) |

| Carcinoid | 1 (0.45) |

| Patient position | |

| Lithotomy | 72 (32.3) |

| Left lateral | 47 (21.1) |

| Right lateral | 31 (13.8) |

| Lloyd-Davies | 8 (3.6) |

| Prone | 9 (4) |

| Missing data | 55 (24.7) |

| R0 | 171 (76.7) |

| Blood loss in ml (mode) | 0 (0-100) |

| Operative time (mean)/minutes | 90 (36-280) |

| Hospital-stay in days (median)/days | 1 (0-133) |

| Salvage TME | 42 (19.8) |

The majority of tumours operated were in the low rectum with median distance from the anal verge 4.5 cm (range: 0.5-30 cm). Median tumour size (x-axis) was 2.6 cm (range: 0.1-14 cm).

TEMS was carried out in 204 primary rectal carcinomas, 16 patients with adenoma, one patient with carcinoid tumour, one patient with recto-vaginal fistula. Pre-operative radiotherapy was offered to 35 patients with T2 Lesions, three of them showed complete clinical response.

The most frequent operative position of the patient was lithotomy (32.3%), followed by left lateral (21.1%). Full-thickness rectal wall excision was done in 204 patients, partial thickness in 12, and the resultant defect was suture-closed in 206 patients. Median operating time was 90 minutes (ranged 36-280 minutes) Average blood loss was minimal and highest figure noted was 100 mL in one case.

Hospital-stay (Table 1) ranged from zero (some patients were managed as a day-case), to a few days, with three outliers; one patient stayed for 14 days, one for 26 days, and one for 133 days. The main cause was postoperative collection and abscess. There were two 90-day mortalities, one was a patient of pT1 rectal carcinoma with synchronous advanced metastatic appendiceal carcinoma that progressed on postoperative chemotherapy, and the other was a patient of tubulo-villous adenoma with chronic obstructive pulmoriary disease and renal impairment, died postoperatively of acute myocardial infarction.

With regards to the pathological outcomes (Table 2), out of 16 pre-operatively diagnosed adenomas 5 patients showed invasive carcinoma. A substantial portion of patients (45.7%) showed pT1, followed by pT2 (30%) which again reflects the main subset of patients who can be safely elected for local excision. pT0 was found in 4.9% of patients (this subset included patients re-operated by TEMS after colonoscopic resection of cancerous polyps in addition to patients who received upfront radiotherapy). While pT3 was shown in 32 patients (14.3%), 10 of them (31.3%) underwent a salvage TME, while others refused or were unfit for major surgery. The data on post operative management of R1 resections is limited. Salvage TME was offered if fit however in frail patients and those who refused surgery, watch and wait approach was adopted. Adjuvant radiotherapy was avoided due to the risk of rectal strictruring and saved as an option for future recurrence treatment. The local recurrence rates in this series are higher than expected and perhaps the use of adjuvant radiotherapy could have improved these figures.

| Pathologic features | n (%) |

| Carcinoid | 1 (0.45) |

| Adenoma | 9 (4) |

| pT0 | 11 (4.9) |

| pT1 | 102 (45.9) |

| pT2 | 67 (30.2) |

| pT3 | 32 (14.4) |

R0 resections (complete trans-anal excision of the tumour with free microscopic margins by > 1 mm) were accomplished in 171 patients (76.7%). Salvage TME was performed in 42 patients (19.8%) due to either high risk pathology findings or patient preference; 19 patients had pT1 (18.6%), 12 patients pT2 (18%), and 10 patients had pT3 tumours (31.2%). TME specimen revealed no residual tumour (T0N0) in 12 patients, a microscopic focus of tumour in one patient, 2 specimens were T3N0, two were T3N1, and one specimen showed no residual primary tumour but a positive lymph node (T0N1).

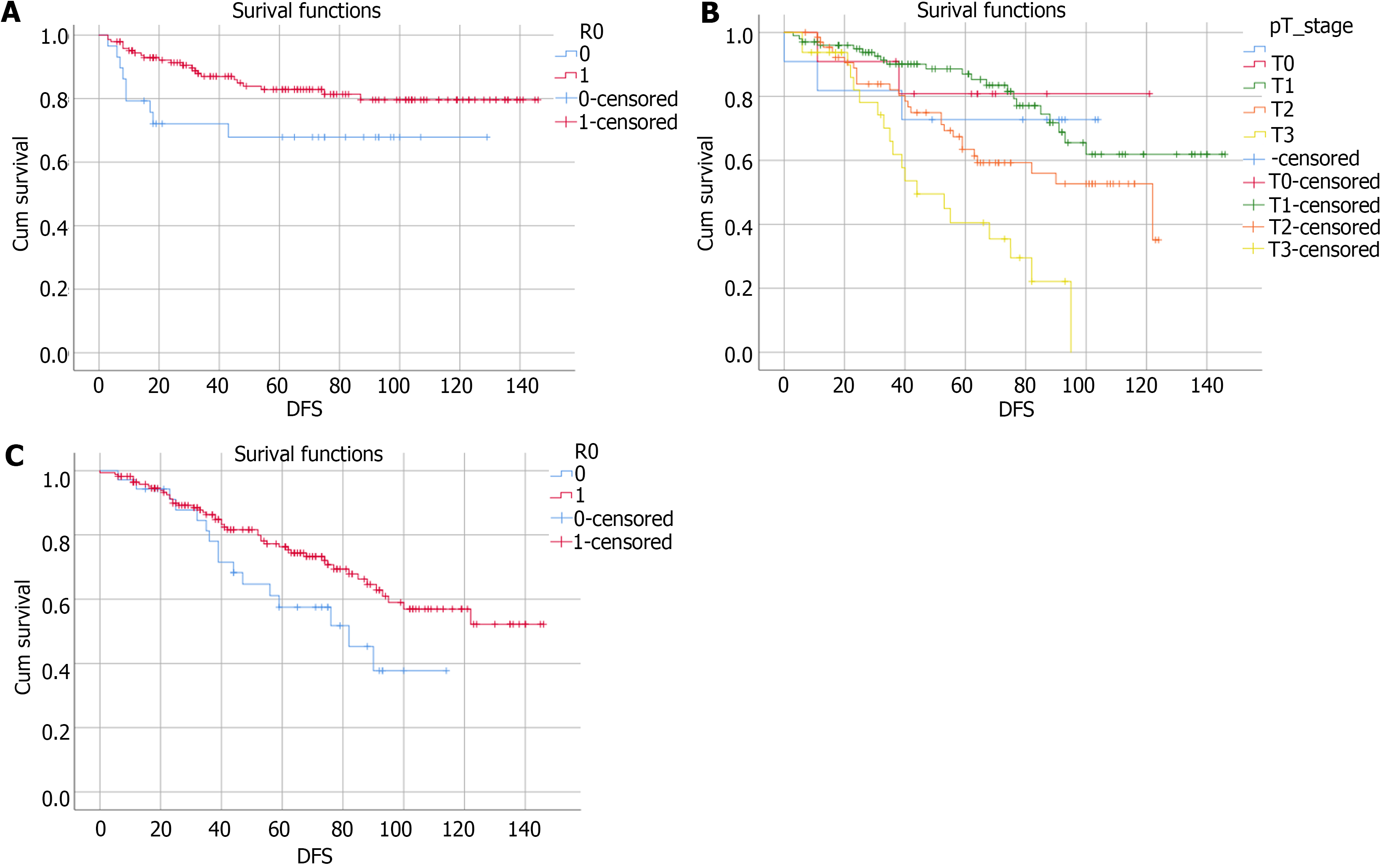

Of 35 patients (15.7%) suffered from disease relapse, 18 patients showed local recurrences, 12 metastatic recurrences, and 5 with synchronous local and metastatic relapse. Median DFS was 65 months (range: 3-146 months) (82.8%), and median OS was 59 months (0-146 months), (68%) (Figure 1). Shortest DFS interval was 3 months. Figure 1 shows the impact of R0 resection and T stage on DFS and OS. This was a patient who developed an early metastatic process on the follow-up scans, the tumour was completely resected (pT2) and the patient survived according to the latest mortality check (Table 3).

| Oncologic outcomes | n (%) |

| Total recurrences | 35 (15.7) |

| Local recurrences only | 19 (8.5) |

| Distant recurrences only | 12 (5.3) |

| Synchronous Local and distant | 4 (1.79) |

| DFS in months (median) | 65 (3-146) |

| OS in months (median) | 59 (0-146) |

This paper summarizes a real-life experience from three large TEMS cancer centres from the United Kingdom, evaluating the short and long-term oncologic outcomes. The increased use of TEMS amongst males’ group (Table 1) is indicator of how the use of trans-anal approach may overcome morbid dissection in a narrow android pelvis, this is the same indication of using TEMS mainly to operate low (extra-peritoneal) tumours, like the majority of the study cases.

Our survival analysis (Table 4) showed no statistically significant difference between males and females with regards to mean DFS [95% confidence interval (CI) for males: 120 (111-129.5); and 95%CI for females: 123.6 (110.9-136.3), P = 0.833], and mean OS [95%CI for males: 96.6 (86.6-106.7) and 95%CI for females: 107.7 (93.6-120.7), P = 0.174]. Tumor distance from anal verge and tumor size did not affect DFS (P = 0.95 and P = 0.17 respectively), while they did affect OS

| Factors affecting survival | DFS | OS | ||

| 95%CI | P value | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | P = 0.35 (NS) | P = 0.022 | ||

| Gender | P = 0.83 (NS) | P = 0.174 (NS) | ||

| Male | 120 (111-129.5) | 96.6 (86.6-106.7) | ||

| Female | 123.6 (110.9-136.3) | 107.7 (93.6-120.7) | ||

| Distance from AV | P = 0.953 (NS) | P = 0.0001 | ||

| Tumour size | P = 0.17 (NS) | P = 0.0001 | ||

| pT | pT0: 111.3 (93-129.4); pT1: 123.8 (111.3-134.3); pT2: 118 (105.4-131.9); pT3: 94 (72.9-116) | P = 0.45 (NS) | pT0: 102 (79.5-125.7); pT1: 115 (104-126); pT2: 86 (75-97.3); pT3: 54.3 (42.5-66) | P = 0.000039 |

| pN0 | 93.6 (76.5-110.7) | 77.6 (58.7-96.5) | ||

| pN1 | 101.7 (81.4-121.9) | P = 0.82 (NS) | 101.7 (86.9-116.5) | P = 0.57 (NS) |

| R0 | 123.2 (114.7-131.6) | 105.7 (96.5-114.9) | ||

| R1 | 92 (72-112) | P = 0.047 | 74.7 (61.2-88.2) | P = 0.045 |

| Salvage TME | 92.5 (74-111.2) | 111 (96.6-125.2) | ||

| No Salvage TME | 110.3 (98-123) | P = 0.121 (NS) | 101.4 (88.7-114.2) | P = 0.21 (NS) |

Linking pT stage to oncologic outcomes implied that tumour stage did not affect DFS (with pT0-2 tumours showing a tendency of longer DFS than pT3, P = 0.45) nor likelihood ratio (LR) (0% for pT0 vs 9.8% for pT1 vs 13% for pT2 vs 14.3% for pT3, P = 0.72). While OS of patients of pT0-1 tumours was double the patients of pT3 tumours (P > 0.0001). This may demonstrate the systemic aggressiveness of more advanced cancers.

Cases of retrieved lymph nodes in TEMS excisional specimen were sparse, so the nodal stage was not evaluated properly and did not reflect any significance on the survival. This is one of the major drawbacks of TEMS; a residual meso-rectal lymph node may be left behind even if there is no radiologic evidence of nodal metastasis. Based on old series, the historical figure for the risk of lymph node involvement is variable in literature, ranging from 8 to 30% for T1 and 14-37% for T2 cancers[14,15]. Moreover, the current imaging techniques are still deficient in predicting mesorectal lymph node metastasis accurately. A recent meta-analysis pooled the studies correlating pre-treatment MRI staging and pathologic findings node-by-node. The study reported sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odd ratio 0.73 (95%CI: 0.68-0.77), 0.74 (95%CI: 0.68-0.80), and 7.85 (95%CI: 5.78-10.66), respectively[16]. The use of positron emission tomography (PET)-CT in evaluating the mesorectal nodal package is not a standard, as well. One of its major limitations is the false positive results as in inflammatory process in the lymph nodes. Current studies focus on coupling metabolic primary tumour volume and the nodal uptake to achieve more accurate prediction[17]. The limitations of current modalities reflect the future role of Radiomics and artificial intelligence algorithms for accurate staging and prediction of response to therapy[18].

One of the main factors that altered LR, DFS, and OS in our study group, was achievement of R0 resections (i.e., complete excision of the tumour with microscopic negative margins). We found that LR of R0 was 7.7% vs 26.9% for R1, which is statistically significant (P = 0.021) (Table 5). R0 resections resulted in a mean DFS of 95%CI: 123.2 (114.7-131.6) vs 95%CI: 92 (72-112) for R1, which showed a statistically significance (P = 0.047). While for OS: 95%CI for R0: 105.7 (96.5-114.9) vs 95%CI for R1: 74.7 (61.2-88.2), which was statistically significant (P = 0.045).

| Factors affecting local recurrences | Number of local recurrences, (%) | P value |

| pT stage | P = NS | |

| pT0 | 0/11 | |

| pT1 | 9/92 (9.8) | |

| pT2 | 8/62 (13) | |

| pT3 | 4/28 (14.2) | |

| R0 resections | 14/157 (9) | P < 0.05 |

| R1 resections | 8/34 (23.5) | |

Despite the highlighted role of completion TME after TEMS for patients with unfavourable tumour features, we did not find a statistically significant difference in survival between patients who underwent salvage TME (P = 0.121 for DFS, and P = 0.21 for OS). But these results may have been altered by the incomplete records and missing data as regards to further surgical procedures for a subset of our study group (Table 4).

Patients with early relapse (within a year after TEMS) are a concern as these early local recurrences are a failure of local excision, while distant recurrences represent a systemic failure of treatment. Broadly speaking, the impact of total local recurrences on mean OS was statistically significant. There was a notable tendency of better survival of local recurrence free patients [95%CI of 106.6 months: (97.7-115.4)] against those with local recurrence [95%CI of 70 months: (55-86)] (P = 0.042).

Twelve patients out of 42 who underwent salvage TME showed no residual cancer in TME specimen pT0N0 (29%), which raises the question about the need for better selection of cases for salvage resection, considering that salvage TME showed no statistically significant impact on survival in our univariate and multivariate analysis. Rullier et al[19,20] addressed the issue of salvage TME and rates of negative TME specimen after neoadjuvant chemoradiation and TEMS, calling this a rather unnecessary salvage TME in a subset of patients and debating the need for such surgery as there was no statistical significance between TEMS and TME after neoadjuvant therapy.

Two recent meta-analyses pooled the studies of early rectal cancer managed by TEMS plus adjuvant radiotherapy. The oncologic outcomes were consistent with our study, provided that systemic therapy/radiation therapy is used[21,22]. In addition, TREC trial employed organ preservation strategies via short course radiotherapy followed by TEMS. It showed comparable outcomes with low risk of unsalvageable recurrences, remarking the feasibility of TEMS as a substitute for TME in selected patients[23].

Our study is a retrospective analysis of subset of patients who underwent TEMS. Case mix for three different centres can led to heterogenicity of the study group (especially tumour stage and perioperative therapy). In addition, some perioperative clinical and follow up records were missing. The data on post operative management of R1 resections is limited. Quality of life, low anterior resection syndrome score and sphincteric functions were not routinely monitored and recorded and may have provided some valuable insights towards organ preserving approaches by TEMS.

TEMS provides a promising option for early rectal cancers (Large adenomas-cT1/cT2N0), and selected therapy-responding cancers. Full-thickness complete excision (R0) of the tumour is mandatory to avoid jeopardising the oncological outcomes.

| 1. | Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery--the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg. 1982;69:613-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1937] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Peeters KC, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EK, Putter H, Wiggers T, Rutten H, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, Leer JW, van de Velde CJ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:693-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 853] [Cited by in RCA: 875] [Article Influence: 48.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Merchant NB, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Enker WE, Minsky BD, Quan SH, Wong D, Cohen AM. T3N0 rectal cancer: results following sharp mesorectal excision and no adjuvant therapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:642-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Buess G, Theiss R, Günther M, Hutterer F, Pichlmaier H. Endoscopic surgery in the rectum. Endoscopy. 1985;17:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moore JS, Cataldo PA, Osler T, Hyman NH. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is more effective than traditional transanal excision for resection of rectal masses. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1026-30; discussion 1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Palma P, Horisberger K, Joos A, Rothenhoefer S, Willeke F, Post S. Local excision of early rectal cancer: is transanal endoscopic microsurgery an alternative to radical surgery? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Winde G, Nottberg H, Keller R, Schmid KW, Bünte H. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinomas (T1). Transanal endoscopic microsurgery vs. anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:969-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Heintz A, Mörschel M, Junginger T. Comparison of results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical resection for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1145-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Middleton PF, Sutherland LM, Maddern GJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:270-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Azad N, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Garrido-Laguna I, Grem JL, Gunn A, Hecht JR, Hoffe S, Hubbard J, Hunt S, Jeck W, Johung KL, Kirilcuk N, Krishnamurthi S, Maratt JK, Messersmith WA, Meyerhardt J, Miller ED, Mulcahy MF, Nurkin S, Overman MJ, Parikh A, Patel H, Pedersen K, Saltz L, Schneider C, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Tavakkoli A, Willett CG, Gregory K, Gurski L. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:1139-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 136.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Garcia-Aguilar J, Renfro LA, Chow OS, Shi Q, Carrero XW, Lynn PB, Thomas CR Jr, Chan E, Cataldo PA, Marcet JE, Medich DS, Johnson CS, Oommen SC, Wolff BG, Pigazzi A, McNevin SM, Pons RK, Bleday R. Organ preservation for clinical T2N0 distal rectal cancer using neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and local excision (ACOSOG Z6041): results of an open-label, single-arm, multi-institutional, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1537-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Verseveld M, de Graaf EJ, Verhoef C, van Meerten E, Punt CJ, de Hingh IH, Nagtegaal ID, Nuyttens JJ, Marijnen CA, de Wilt JH; CARTS Study Group. Chemoradiation therapy for rectal cancer in the distal rectum followed by organ-sparing transanal endoscopic microsurgery (CARTS study). Br J Surg. 2015;102:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Smart CJ, Korsgen S, Hill J, Speake D, Levy B, Steward M, Geh JI, Robinson J, Sebag-Montefiore D, Bach SP. Multicentre study of short-course radiotherapy and transanal endoscopic microsurgery for early rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103:1069-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Blumberg D, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Picon AI, Minsky BD, Wong WD, Cohen AM. All patients with small intramural rectal cancers are at risk for lymph node metastasis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:881-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Saraste D, Gunnarsson U, Janson M. Predicting lymph node metastases in early rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1104-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhuang Z, Zhang Y, Wei M, Yang X, Wang Z. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Evaluation of the Accuracy of Various Lymph Node Staging Criteria in Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:709070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim SH, Song BI, Kim BW, Kim HW, Won KS, Bae SU, Jeong WK, Baek SK. Predictive Value of [(18)F]FDG PET/CT for Lymph Node Metastasis in Rectal Cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu X, Yang Q, Zhang C, Sun J, He K, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Fu Y, Zhang H. Multiregional-Based Magnetic Resonance Imaging Radiomics Combined With Clinical Data Improves Efficacy in Predicting Lymph Node Metastasis of Rectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:585767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rullier E, Rouanet P, Tuech JJ, Valverde A, Lelong B, Rivoire M, Faucheron JL, Jafari M, Portier G, Meunier B, Sileznieff I, Prudhomme M, Marchal F, Pocard M, Pezet D, Rullier A, Vendrely V, Denost Q, Asselineau J, Doussau A. Organ preservation for rectal cancer (GRECCAR 2): a prospective, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:469-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rullier E, Vendrely V, Asselineau J, Rouanet P, Tuech JJ, Valverde A, de Chaisemartin C, Rivoire M, Trilling B, Jafari M, Portier G, Meunier B, Sieleznieff I, Bertrand M, Marchal F, Dubois A, Pocard M, Rullier A, Smith D, Frulio N, Frison E, Denost Q. Organ preservation with chemoradiotherapy plus local excision for rectal cancer: 5-year results of the GRECCAR 2 randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:465-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cutting JE, Hallam SE, Thomas MG, Messenger DE. A systematic review of local excision followed by adjuvant therapy in early rectal cancer: are pT1 tumours the limit? Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:854-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xiong X, Wang C, Wang B, Shen Z, Jiang K, Gao Z, Ye Y. Can transanal endoscopic microsurgery effectively treat T1 or T2 rectal cancer?A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2021;37:101561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bach SP, Gilbert A, Brock K, Korsgen S, Geh I, Hill J, Gill T, Hainsworth P, Tutton MG, Khan J, Robinson J, Steward M, Cunningham C, Levy B, Beveridge A, Handley K, Kaur M, Marchevsky N, Magill L, Russell A, Quirke P, West NP, Sebag-Montefiore D; TREC collaborators. Radical surgery versus organ preservation via short-course radiotherapy followed by transanal endoscopic microsurgery for early-stage rectal cancer (TREC): a randomised, open-label feasibility study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:92-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |