Published online Sep 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i9.2042

Peer-review started: May 24, 2023

First decision: June 12, 2023

Revised: June 23, 2023

Accepted: July 27, 2023

Article in press: July 27, 2023

Published online: September 27, 2023

Processing time: 121 Days and 8.5 Hours

Microvascular invasion (MVI) is an important predictor of poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Accurate preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC would provide useful information to guide the choice of therapeutic strategy. Shear wave elastography (SWE) plays an important role in hepatic imaging, but its value in the preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC has not yet been proven.

To explore the value of conventional ultrasound features and SWE in the preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC.

Patients with a postoperative pathological diagnosis of HCC and a definite diagnosis of MVI were enrolled in this study. Conventional ultrasound features and SWE features such as maximal elasticity (Emax) of HCCs and Emax of the periphery of HCCs were acquired before surgery. These features were compared between MVI-positive HCCs and MVI-negative HCCs and between mild MVI HCCs and severe MVI HCCs.

This study included 86 MVI-negative HCCs and 102 MVI-positive HCCs, including 54 with mild MVI and 48 with severe MVI. Maximal tumor diameters, surrounding liver tissue, color Doppler flow, Emax of HCCs, and Emax of the periphery of HCCs were significantly different between MVI-positive HCCs and MVI-negative HCCs. In addition, Emax of the periphery of HCCs was significantly different between mild MVI HCCs and severe MVI HCCs. Higher Emax of the periphery of HCCs and larger maximal diameters were independent risk factors for MVI, with odds ratios of 2.820 and 1.021, respectively.

HCC size and stiffness of the periphery of HCC are useful ultrasound criteria for predicting positive MVI. Preoperative ultrasound and SWE can provide useful information for the prediction of MVI in HCCs.

Core Tip: Shear wave elastography (SWE) plays an important role in differentiating benign and malignant liver tumors and different types of malignant liver tumors. However, its value in the preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion (MVI) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has not yet been proven. We used conventional ultrasound and SWE to evaluate the features of HCCs for preoperative prediction of MVI in HCCs. Our results showed that higher maximal elasticity of the periphery of HCCs and larger maximal diameters were independent risk factors for MVI. Preoperative conventional ultrasound and SWE can provide useful information for the prediction of MVI in HCCs.

- Citation: Jiang D, Qian Y, Tan BB, Zhu XL, Dong H, Qian R. Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma using ultrasound features including elasticity. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(9): 2042-2051

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i9/2042.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i9.2042

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide and the second leading cause in China, represents a major health concern throughout the world, especially in China[1]. Microvascular invasion (MVI), the invasion of cancer cells into vascular lumen (including microbranches of the portal vein, hepatic artery, and lymphatic vessels), is a very important predictor of poor prognosis, postoperative recurrence, metastasis, and poor survival rate in patients with HCC after surgical resection or liver transplantation[2-5]. Accurate preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC would offer valuable insights to guide therapeutic strategy.

Some studies have demonstrated that preoperative imaging including contrast-enhanced computed tomography and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help in the diagnosis of MVI[6-10]. Related studies have focused on contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS)[11-14]. The study by Qin et al[11] showed that a deep learning model based on CEUS could accurately predict MVI in HCC and help identify high-risk patients. The study by Li et al[12] showed that features such as non-single nodules in the postvascular phase of preoperative Sonazoid CEUS was an independent risk factor for MVI in HCC.

Ultrasound elastography, especially quantitative shear wave elastography (SWE), plays an important role in hepatic imaging[15-17]. Compared with CEUS, contrast-enhanced computed tomography, or contrast-enhanced MRI, SWE has the advantage of the absence of contrast agent allergy and is generally less expensive and less time-consuming than other methods, making it a more practical option for many medical facilities. Zhang et al[7] reported that the stiffness of HCCs based on MR-elastography was an independent risk factor for MVI and may be useful for the preoperative prediction of MVI. However, only a few studies have focused on the value of SWE in the prediction of MVI[18].

In the present study, we explored the value of conventional ultrasound features and SWE in the preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC.

This prospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital (Approval No. EHBHKY2021-K-017). Each patient provided written informed consent before the ultrasound examinations.

Inpatients admitted to the Hepatobiliary Surgery Department at our hospital between November 2021 and July 2022 were included in this study if they met the following criteria: (1) Single liver tumor resected surgically and diagnosed as HCC pathologically; and (2) Ultrasound examinations including SWE successfully performed within 3 d before surgery. The exclusion criteria were: (1) A history of hepatectomy or abdominal malignant tumors; (2) A history of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and other treatments before surgery; and (3) No definite pathological diagnosis of MVI.

All ultrasound examinations were performed within 3 d before surgery, using an Acuson Sequoia diagnostic ultrasound machine and a transabdominal 5C1 probe (Siemens Medical Solutions, Mountain View, CA, United States). The patients were instructed to fast for a minimum of 8 h prior to the examinations.

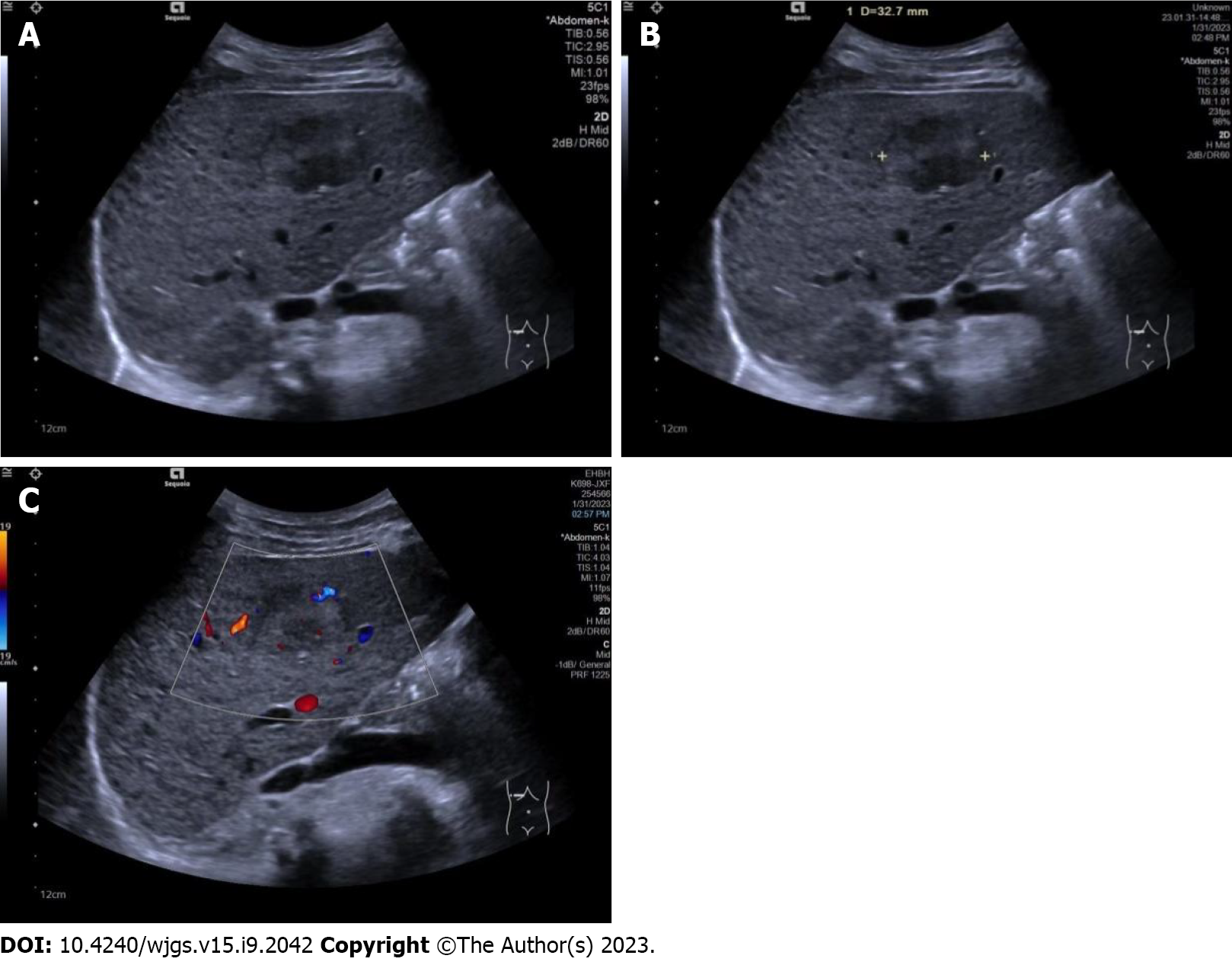

All conventional ultrasound examinations were performed by a single ultrasound physician with 15 years of experience in liver ultrasound. Maximal tumor diameter, echogenicity (hypo- if the tumor was mainly hypoechoic compared with surrounding liver tissue, or hyper- if the tumor was mainly hyperechoic compared with surrounding liver tissue), boundary (clear or unclear), surrounding hepatic tissue (liver cirrhosis, fatty liver, or normal liver), and tumor vascularity (none if no vessels were seen in the tumor using color Doppler flow imaging, rich if more than three vessels were seen, or mild if one to three vessels were seen) were observed and recorded (Figure 1).

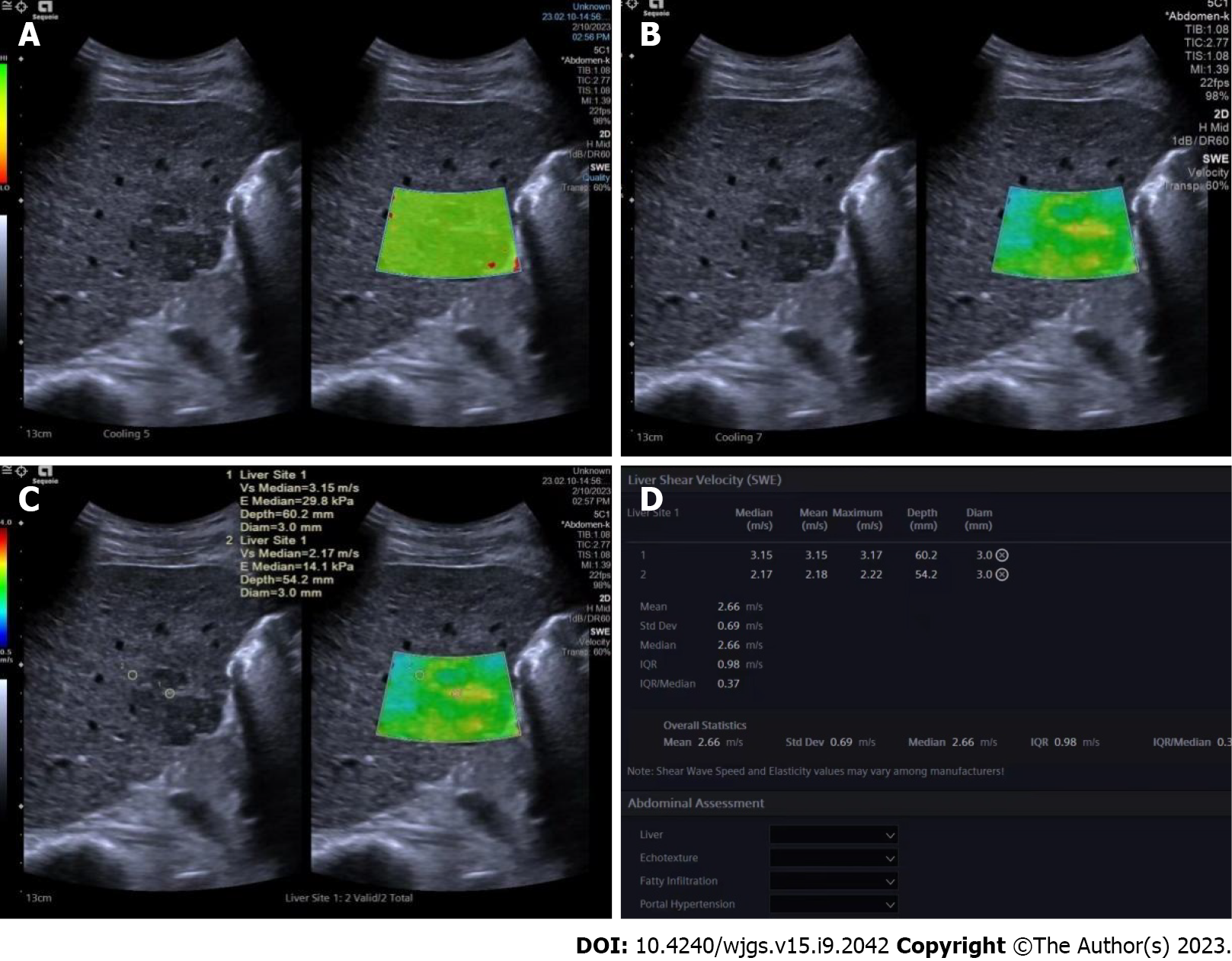

The same ultrasound equipment and probe were used for the SWE examination. Another ultrasound physician with 5 years of experience in both liver ultrasound and ultrasound elastography performed all the SWE examinations. During the examination, the patients were instructed to lie flat and breathe gently. They were instructed to hold their breath for a few seconds if necessary. The targeted tumor was shown on the screen before activation of the SWE mode. The whole tumor (or partial if the tumor was too large) and some surrounding hepatic tissues were included in the region of interest (ROI). Quality mode was used to evaluate the SWE image quality; green in the ROI means image quality is excellent and the results are reliable. In the velocity mode, the speed bar was set as 0.5-4.0 m/s. One circular ROI (diameter of 3 mm) was placed at the stiffest part of the tumor; another ROI of the same size was placed at the periphery of the tumor. The maximum values within the two ROIs were recorded as Emax for both the tumor and the periphery of the tumor, respectively. These values were then used for further analysis (Figure 2).

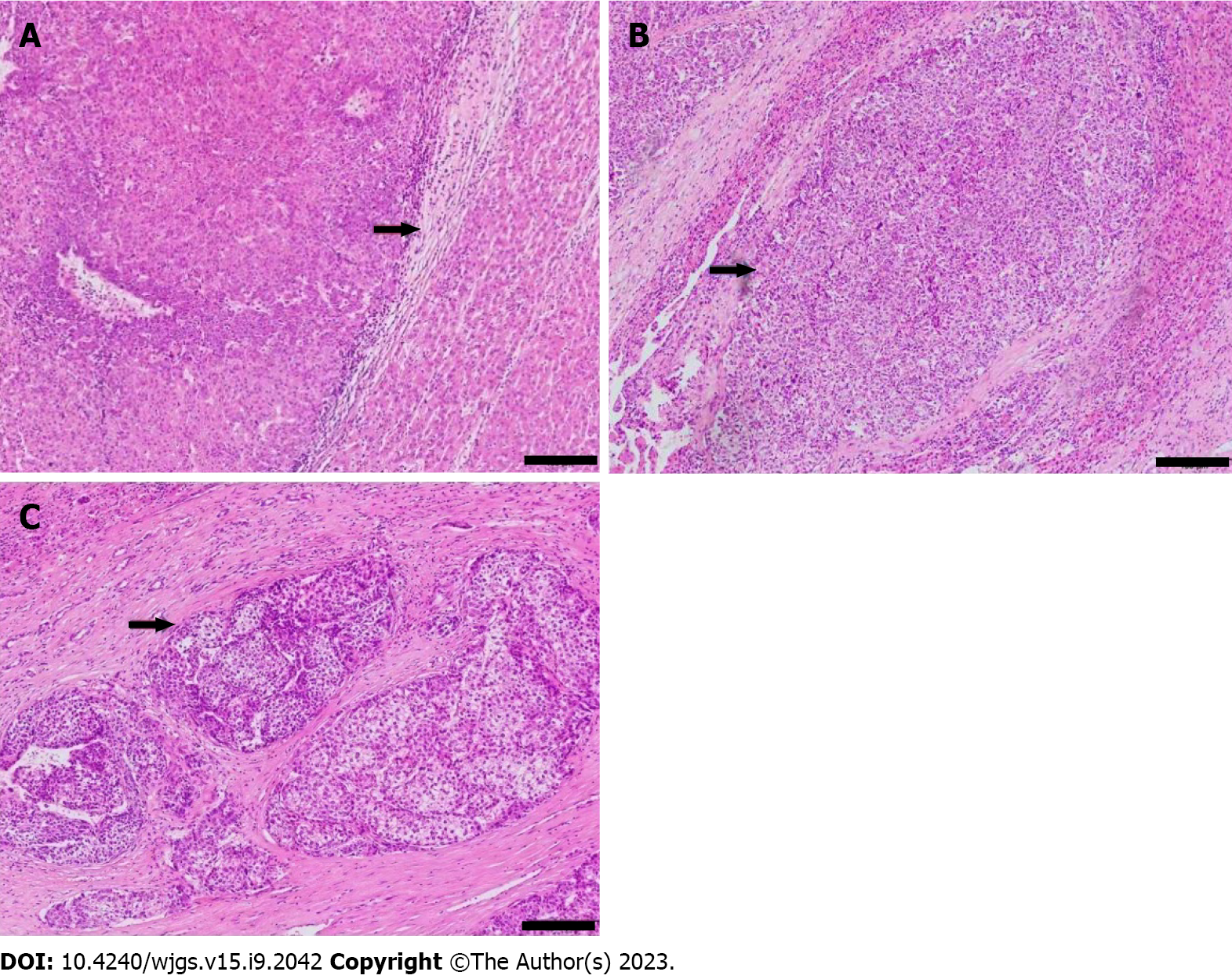

One pathologist, who had 20 years of experience in HCC pathology and was blind to all clinical data, reviewed the specimens. The extent of MVI was graded as MVI-negative (no MVI detected), mild MVI (MVI ≤ 5, occurring in the proximal non-neoplastic adjacent hepatic tissues), and severe MVI (MVI > 5, in non-neoplastic adjacent hepatic tissues, Figure 3)[2].

For statistical analysis, SPSS version 24.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States) was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Measurement data with normal distribution were reported as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the independent sample t-test; otherwise, data were reported as median (25th-75th percentile) and compared using the Mann-Whitney test. The cutoff point of Emax was calculated by a receiver operating characteristic curve.

Enumerative data were described as numbers and percentage and compared using the Pearson c2 test. Bivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine independent predictors of MVI from the ultrasound characteristics that showed statistical significance using univariate analysis.

One hundred and eighty-eight patients with single HCCs (156 males and 32 females; aged 24-76 years, mean age 56.25 years ± 9.93 years) were enrolled in this study, including 86 who were MVI-negative and 102 who were MVI-positive (54 had mild MVI and 48 had severe MVI). Sex and age were not significantly different between the MVI-negative patients (70 males and 16 females; mean age 56.94 years ± 10.12 years) and the MVI-positive patients (86 males and 16 females; mean age 55.67 years ± 9.77 years).

Comparisons of conventional ultrasound results between MVI-negative and MVI-positive HCCs are shown in Table 1. The maximal diameters of MVI-positive HCCs were significantly greater than those of MVI-negative HCCs. The cutoff point for maximal tumor diameters was 61.95 mm with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.663. MVI-positive HCCs were more likely to have a background of liver cirrhosis and a rich blood flow and less likely to have a fatty liver background.

| MVI | Tumor maximal diameter in mm | Echogenecity | Boundary | Surrounding liver tissue | Color Doppler flow | ||||||

| Hypo- | Hyper- | Clear | Unclear | Liver cirrhosis | Fatty liver | Normal | None | Mild | Rich | ||

| MVI negative, n = 86 | 35.45 (24.00-49.28) | 55 (29.3) | 31 (16.5) | 55 (29.3) | 31 (16.5) | 38 (20.2) | 17 (9.0) | 31 (16.5) | 34 (18.1) | 12 (6.4) | 40 (21.3) |

| MVI positive, n = 102 | 46.95 (32.75-71.03) | 63 (33.5) | 39 (20.7) | 58 (30.9) | 44 (23.4) | 52 (27.7) | 7 (3.7) | 43 (22.9) | 20 (10.6) | 20 (10.6) | 62 (33.0) |

| Z/χ2 | 3.841 | 0.096 | 0.978 | 7.255 | 9.079 | ||||||

| P value | 0.000 | 0.757 | 0.323 | 0.027 | 0.011 | ||||||

Comparisons of conventional ultrasound results between mild MVI and severe MVI HCCs are shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in either maximal tumor diameter or other ultrasound characteristics between the two groups.

| MVI | Tumor maximal diameter in mm | Echogenecity | Boundary | Surrounding liver tissue | Color Doppler flow | ||||||

| Hypo- | Hyper- | Clear | Unclear | Liver cirrhosis | Fatty liver | Normal | None | Mild | Rich | ||

| Mild MVI, n = 54 | 50.15 (33.80-65.90) | 36 (35.3) | 18 (17.6) | 33 (32.4) | 21 (20.6) | 25 (24.5) | 4 (3.9) | 25 (24.5) | 8 (7.8) | 9 (8.8) | 37 (36.3) |

| Severe MVI, n = 48 | 43.20 (30.83-73.68) | 27 (26.5) | 21 (20.6) | 25 (24.5) | 23 (22.5) | 27 (26.5) | 3 (2.9) | 18 (17.6) | 12 (11.8) | 11 (10.8) | 25 (24.5) |

| Z/χ2 | 0.496 | 1.168 | 0.844 | 1.063 | 2.980 | ||||||

| P value | 0.622 | 0.280 | 0.358 | 0.641 | 0.254 | ||||||

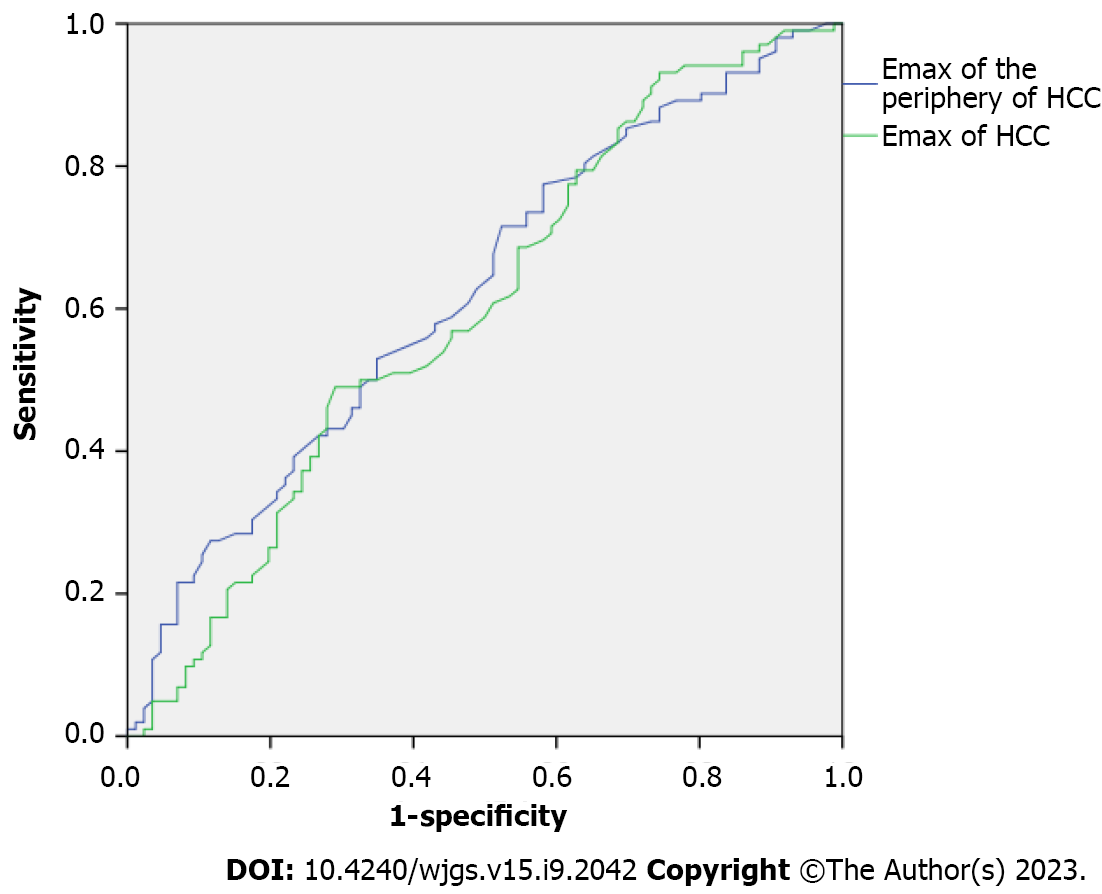

The differences in SWE results between MVI-negative and MVI-positive HCCs are shown in Table 3. The Emax of MVI-positive HCCs was significantly higher than that of MVI-negative HCCs. The Emax of the periphery of MVI-positive HCCs was significantly higher than that of MVI-negative HCCs. The cutoff point for the Emax of HCCs was 2.340 with an AUC of 0.598; the cutoff point for the Emax of the periphery of HCCs was 1.305 with an AUC of 0.622 (Figure 4).

| MVI | Emax of the periphery of tumors in m/s | Emax of the tumors in m/s |

| MVI negative, n = 86 | 1.38 (1.18-1.65) | 2.14 (1.71-2.49) |

| MVI positive, n = 102 | 1.50 (1.31-1.88) | 2.29 (2.00-2.63) |

| Z | 2.879 | 2.312 |

| P value | 0.004 | 0.021 |

The differences in SWE results between mild MVI and severe MVI HCCs are shown in Table 4. There were no significant differences between the Emax of mild MVI and severe MVI HCCs. However, the Emax of the periphery of severe MVI HCCs was significantly higher than that of mild MVI HCCs.

| MVI | Emax of the periphery of tumors in m/s | Emax of the tumors in m/s |

| Mild MVI, n = 54 | 1.42 (1.23-1.84) | 2.24 (2.00-2.56) |

| Severe MVI, n = 48 | 1.67 (1.37-1.98) | 2.37 (2.03-2.67) |

| Z | 2.437 | 0.811 |

| P value | 0.014 | 0.420 |

The results of bivariate logistic regression of the features suggestive of positive MVI are shown in Table 5. Higher Emax of the periphery of HCCs and larger maximal diameters were independent risk factors for MVI, with odds ratios of 2.820 and 1.021, respectively.

| Ultrasound features | β coefficient | Odd ratios | 95% confidence interval | P value |

| Emax of the periphery of HCC | 1.037 ± 0.467 | 2.820 | 1.128-7.049 | 0.027 |

| Emax of HCC | 0.114 ± 0.272 | 0.893 | 0.524-1.521 | 0.676 |

| Maximal tumor diameter | 0.021 ± 0.008 | 1.021 | 1.003-1.037 | 0.007 |

| Surrounding liver tissue | 0.329 ± 0.230 | 0.719 | 0.459-1.128 | 0.152 |

| Color Doppler flow | 0.324 ± 0.190 | 1.383 | 0.953-2.006 | 0.088 |

In this study, we investigated the efficacy of conventional ultrasound features and SWE in the preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC. Our findings revealed that a higher Emax in the periphery of HCCs coupled with larger maximal diameters were independent risk factors for MVI.

There were no significant differences in the distributions of sex and age between patients with MVI-positive HCCs and those with MVI-negative HCCs. These results were similar to those in a previous study[19]. Our results also showed that the maximal diameters of MVI-positive HCCs were significantly larger than those of MVI-negative HCC, and a larger maximal diameter was an independent risk factor for MVI-positive HCCs with an odds ratio of 1.021. Tumor size is an established independent prognostic factor for HCC[20,21]. Our research has revealed that HCC size was also an independent prognostic factor for positive MVI. Consequently, it is of utmost importance to have precise preoperative measurements of HCC size for accurate prediction of MVI status and prognosis.

Conventional ultrasound is the first imaging choice for hepatology and plays an important role in both focal hepatic lesions and diffuse liver diseases. Our study showed that ultrasound features such as tumor boundary or tumor echogenicity were not significantly different between MVI-positive and MVI-negative HCCs, similar to the results of Zhou et al[22], which showed that ultrasound features including echogenicity, margin, shape, and halo sign were not significantly different between MVI-positive and MVI-negative HCCs. According to our findings, MVI-positive HCCs were more likely to have a rich blood flow. As MVI reflects the invasion of cancer cells into microvessels, it may cause a change in the blood supply in tumors. Some CEUS studies have also confirmed that MVI-positive HCCs have increased blood flow perfusion, compared with MVI-negative HCCs[13,14]. However, the study by Zhou et al[22] showed different results as the distribution of blood flow was not significantly different between MVI-positive and MVI-negative HCCs. The reason for this may be due to the different ultrasound machines used. The sensitivity of color Doppler can vary greatly between ultrasound machines. Also, the correct setting of machine parameters is very important[23]. The application of new Doppler techniques, such as superb microvascular imaging, would be useful[24]. Our study revealed that MVI-positive HCCs were more likely to have a background of liver cirrhosis and less likely to have a background of fatty liver, indicating that HCCs with a background of liver cirrhosis are likely MVI-positive. The surrounding liver background of HCCs should be taken into consideration for preoperative evaluation.

Our previous studies have shown that the value of SWE with Emax in the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant focal liver lesions or among different pathological types of malignant focal liver lesions[15]. In this study, we found that the Emax of HCCs and the Emax of the periphery of HCCs were significantly different between MVI-positive HCCs and MVI-negative HCCs. The Emax of the periphery of HCCs was an independent risk factor for MVI-positive HCC with an odds ratio of 2.820. Our results indicated that MVI-positive HCCs were stiffer than MVI-negative HCCs, and this was similar to the results of other studies based on MR-elastography[7,25]. One probable reason is that positive MVI may change the blood supply in the tumor and then modify its stiffness. As MVI usually invades the capsule of HCCs first, the periphery of the HCC is usually involved early[2]. This early change in blood flow and tissue stiffness could potentially have significant implications. Zhang et al[26] reported rim enhancement in the arterial phase and peritumoral hypointensity in the hepatobiliary phase in gadobenate-enhanced MRI as independent risk factors for MVI. In addition, our findings suggest that the stiffness of the periphery of HCCs may serve as an important independent predictor of MVI risk. Specifically, we observed that higher stiffness in this region of HCCs was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing MVI. Furthermore, differences in Emax values at the periphery of HCCs were found to distinguish between HCCs with mild and severe MVI, highlighting the potential diagnostic value of this parameter in MVI detection.

There were some limitations to our study that should be acknowledged. First, laboratory data, including total bilirubin and alpha fetoprotein, were not taken into account. The inclusion of these laboratory indices in conjunction with the ultrasound indices would be valuable in developing a predictive model. This will be a focus of our future research.

In summary, HCC size and stiffness of the periphery of HCCs are useful ultrasound criteria for predicting positive MVI. Thus, preoperative ultrasound and SWE could provide useful information for the prediction of MVI in HCCs.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide and the second leading cause in China, represents a major health concern throughout the world, especially in China. Microvascular invasion (MVI) is a very important predictor of poor prognosis in patients with HCC after surgical resection or liver trans

Shear wave elastography (SWE) has the advantage of the absence of contrast agent allergy and is generally less expensive and less time-consuming than other methods, making it a more practical option for many medical facilities. Our previous study showed promising results using SWE with maximal elasticity (Emax) as the parameter to differentiate malignant focal liver lesions from benign lesions and to differentiate among different pathological types of malignant focal liver lesions. However, only a few studies have focused on the value of SWE in the prediction of MVI.

We aimed to explore the value of conventional ultrasound features and SWE in the preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC.

In this study, we enrolled patients with a postoperative pathological diagnosis of HCC and a definite diagnosis of MVI. Conventional ultrasound features and SWE features such as Emax of HCCs and Emax of the periphery of HCCs were acquired before surgery. These features were compared between MVI-positive HCCs and MVI-negative HCC and between mild MVI HCCs and severe MVI HCCs.

There were a total of 86 MVI-negative HCCs and 102 MVI-positive HCCs in this study, including 54 with mild MVI and 48 with severe MVI. Maximal tumor diameters, surrounding liver tissue, color Doppler flow, Emax of HCCs, and Emax of the periphery of HCCs were significantly different between MVI-positive HCCs and MVI-negative HCCs. In addition, Emax of the periphery of HCCs was significantly different between mild MVI HCCs and severe MVI HCCs. Higher Emax of the periphery of HCCs (> 2.340 m/s, area under the curve as 0.598) and larger maximal diameters (> 61.95 mm, area under the curve as 0.663) were independent risk factors for MVI, with odds ratios of 2.820 and 1.021, respectively.

HCC size and stiffness of the periphery of HCCs are useful ultrasound criteria for predicting positive MVI. Thus, preoperative ultrasound and SWE could provide useful information for the prediction of MVI in HCCs.

In this study, we demonstrated the value of conventional ultrasound features and SWE in the preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC. Prospective studies to explore the value of multimodal ultrasound imaging including conventional ultrasound, ultrasound elastography, superb microvascular imaging, and contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the preoperative prediction of MVI in HCC would be beneficial.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Garcia-Tsao G, United States; Tam PKH, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | International Agency for Research on Cancer; World Health Organization. Liver Source: Globocan 2020. [cited 7 July 2023]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/11-Liver-fact-sheet.pdf. |

| 2. | Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, Cong W, Wang J, Zeng M, Zhou W, Bie P, Liu L, Wen T, Han G, Wang M, Liu R, Lu L, Ren Z, Chen M, Zeng Z, Liang P, Liang C, Yan F, Wang W, Ji Y, Yun J, Cai D, Chen Y, Cheng W, Cheng S, Dai C, Guo W, Hua B, Huang X, Jia W, Li Y, Liang J, Liu T, Lv G, Mao Y, Peng T, Ren W, Shi H, Shi G, Tao K, Wang X, Xiang B, Xing B, Xu J, Yang J, Yang Y, Ye S, Yin Z, Zhang B, Zhang L, Zhang S, Zhang T, Zhao Y, Zheng H, Zhu J, Zhu K, Shi Y, Xiao Y, Dai Z, Teng G, Cai J, Cai X, Li Q, Shen F, Qin S, Dong J, Fan J. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (2019 Edition). Liver Cancer. 2020;9:682-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 568] [Article Influence: 113.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Chen ZH, Zhang XP, Wang H, Chai ZT, Sun JX, Guo WX, Shi J, Cheng SQ. Effect of microvascular invasion on the postoperative long-term prognosis of solitary small HCC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:935-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Beaufrère A, Caruso S, Calderaro J, Poté N, Bijot JC, Couchy G, Cauchy F, Vilgrain V, Zucman-Rossi J, Paradis V. Gene expression signature as a surrogate marker of microvascular invasion on routine hepatocellular carcinoma biopsies. J Hepatol. 2022;76:343-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wu F, Sun H, Zhou C, Huang P, Xiao Y, Yang C, Zeng M. Prognostic factors for long-term outcome in bifocal hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. Eur Radiol. 2023;33:3604-3616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu HF, Zhang YZ, Wang Q, Zhu ZH, Xing W. A nomogram model integrating LI-RADS features and radiomics based on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for predicting microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma falling the Milan criteria. Transl Oncol. 2023;27:101597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang L, Li M, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Xiao Y, Dong M, Zhang L, Wang J. The value of quantitative MR elastography-based stiffness for assessing the microvascular invasion grade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2023;33:4103-4114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shi H, Duan Y, Shi J, Zhang W, Liu W, Shen B, Liu F, Mei X, Li X, Yuan Z. Role of preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma based on the texture of FDG PET image: A comparison of quantitative metabolic parameters and MRI. Front Physiol. 2022;13:928969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park S, Kim JH, Kim J, Joseph W, Lee D, Park SJ. Development of a deep learning-based auto-segmentation algorithm for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and application to predict microvascular invasion of HCC using CT texture analysis: preliminary results. Acta Radiol. 2023;64:907-917. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Liu P, Tan XZ, Zhang T, Gu QB, Mao XH, Li YC, He YQ. Prediction of microvascular invasion in solitary hepatocellular carcinoma ≤ 5 cm based on computed tomography radiomics. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:2015-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qin X, Zhu J, Tu Z, Ma Q, Tang J, Zhang C. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound with Deep Learning with Attention Mechanisms for Predicting Microvascular Invasion in Single Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Acad Radiol. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li X, Han X, Li L, Su C, Sun J, Zhan C, Feng D, Cheng W. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography with Sonazoid for Diagnosis of Microvascular Invasion in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2022;48:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dong Y, Qiu Y, Yang D, Yu L, Zuo D, Zhang Q, Tian X, Wang WP, Jung EM. Potential application of dynamic contrast enhanced ultrasound in predicting microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2021;77:461-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dong Y, Zuo D, Qiu YJ, Cao JY, Wang HZ, Yu LY, Wang WP. Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion (MVI) in hepatocellular carcinoma based on kupffer phase radiomics features of sonazoid contrast-enhanced ultrasound (SCEUS): A prospective study. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2022;81:97-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Guo J, Jiang D, Qian Y, Yu J, Gu YJ, Zhou YQ, Zhang HP. Differential diagnosis of different types of solid focal liver lesions using two-dimensional shear wave elastography. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:4716-4725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Naganuma H, Ishida H. Factors other than fibrosis that increase measured shear wave velocity. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:6512-6521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fang C, Rafailidis V, Konstantatou E, Yusuf GT, Barrow I, Pagkalidou E, Romanos O, Agarwal K, Quaglia A, Sidhu PS. Comparison Between Different Manufacturers' 2-D and Point Shear Wave Elastography Techniques in Staging Liver Fibrosis in Chronic Liver Disease Using Liver Biopsy as the Reference Standard: A Prospective Study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2022;48:2229-2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu C, Jiang D, Tan B, Shen C, Guo J. Preoperative diagnosis and prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellularcarcinoma by ultrasound elastography. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang WT, Yang L, Yang ZX, Hu XX, Ding Y, Yan X, Fu CX, Grimm R, Zeng MS, Rao SX. Assessment of Microvascular Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Diffusion Kurtosis Imaging. Radiology. 2018;286:571-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang X, Fu Y, Zhu C, Hu X, Zou H, Sun C. New insights into a microvascular invasion prediction model in hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective study from the SEER database and China. Front Surg. 2023;9:1046713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hu J, Gong N, Li D, Deng Y, Chen J, Luo D, Zhou W, Xu K. Identifying hepatocellular carcinoma patients with survival benefits from surgery combined with chemotherapy: based on machine learning model. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhou H, Sun J, Jiang T, Wu J, Li Q, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Cao J, Sun Y, Jiang Y, Liu Y, Zhou X, Huang P. A Nomogram Based on Combining Clinical Features and Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound LI-RADS Improves Prediction of Microvascular Invasion in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:699290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bhide A, Acharya G, Baschat A, Bilardo CM, Brezinka C, Cafici D, Ebbing C, Hernandez-Andrade E, Kalache K, Kingdom J, Kiserud T, Kumar S, Lee W, Lees C, Leung KY, Malinger G, Mari G, Prefumo F, Sepulveda W, Trudinger B. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): use of Doppler velocimetry in obstetrics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;58:331-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jeon SK, Lee JY, Kang HJ, Han JK. Additional value of superb microvascular imaging of ultrasound examinations to evaluate focal liver lesions. Eur J Radiol. 2022;152:110332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gao S, Zhang Y, Sun W, Jin K, Dai Y, Wang F, Qian X, Han J, Sheng R, Zeng M. Assessment of an MR Elastography-Based Nomogram as a Potential Imaging Biomarker for Predicting Microvascular Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;58:392-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang L, Yu X, Wei W, Pan X, Lu L, Xia J, Zheng W, Jia N, Huo L. Prediction of HCC microvascular invasion with gadobenate-enhanced MRI: correlation with pathology. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:5327-5336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |