Published online Sep 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i9.1969

Peer-review started: May 3, 2023

First decision: June 13, 2023

Revised: June 29, 2023

Accepted: July 27, 2023

Article in press: July 27, 2023

Published online: September 27, 2023

Processing time: 142 Days and 10.4 Hours

It remains unclear whether laparoscopic multisegmental resection and ana

To compare the short-term efficacy and long-term prognosis of OMRA as well as LMRA for SCRC located in separate segments.

Patients with SCRC who underwent surgery between January 2010 and December 2021 at the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the Peking University First Hospital were retrospectively recruited. In accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 109 patients who received right hemicolectomy together with anterior resection of the rectum or right hemicolectomy and sigmoid colectomy were finally included in the study. Patients were divided into the LMRA and OMRA groups (n = 68 and 41, respectively) according to the surgical method used. The groups were compared regarding the surgical procedure’s short-term efficacy and its effect on long-term patient survival.

LMRA patients showed markedly less intraoperative blood loss than OMRA patients (100 vs 200 mL, P = 0.006). Compared to OMRA patients, LMRA patients exhibited markedly shorter postoperative first exhaust time (2 vs 3 d, P = 0.001), postoperative first fluid intake time (3 vs 4 d, P = 0.012), and postoperative hospital stay (9 vs 12 d, P = 0.002). The incidence of total postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo grade: ≥ II) was 2.9% and 17.1% (P = 0.025) in the LMRA and OMRA groups, respectively, while the incidence of anastomotic leakage was 2.9% and 7.3% (P = 0.558) in the LMRA and OMRA groups, respectively. Furthermore, the LMRA group had a higher mean number of lymph nodes dissected than the OMRA group (45.2 vs 37.3, P = 0.020). The 5-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates in OMRA patients were 82.9% and 78.3%, respectively, while these rates in LMRA patients were 78.2% and 72.8%, respectively. Multivariate prognostic analysis revealed that N stage [OS: HR hazard ratio (HR) = 10.161, P = 0.026; DFS: HR = 13.017, P = 0.013], but not the surgical method (LMRA/OMRA) (OS: HR = 0.834, P = 0.749; DFS: HR = 0.812, P = 0.712), was the independent influencing factor in the OS and DFS of patients with SCRC.

LMRA is safe and feasible for patients with SCRC located in separate segments. Compared to OMRA, the LMRA approach has more advantages related to short-term efficacy.

Core Tip: The efficacy and safety of laparoscopic multisegmental resection and anastomosis (LMRA) in patients with synchronous colorectal cancer involving separate segments has not been fully evaluated. We compared the short-term efficacy and long-term prognosis between LMRA and open multisegmental resection and anastomosis, and found that the LMRA approach has more advantages related to faster postoperative recovery, less intraoperative blood loss, reduced postoperative hospital stay, fewer postoperative complications, and a greater total number of lymph nodes dissected.

- Citation: Quan JC, Zhou XJ, Mei SW, Liu JG, Qiu WL, Zhang JZ, Li B, Li YG, Wang XS, Chang H, Tang JQ. Short- and long-term results of open vs laparoscopic multisegmental resection and anastomosis for synchronous colorectal cancer located in separate segments. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(9): 1969-1977

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i9/1969.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i9.1969

Synchronous colorectal cancer (SCRC), a colorectal malignancy, refers to the simultaneous presence of multiple primary colorectal cancers (CRCs) in one patient. SCRC lesions can be located in the same segments, adjacent segments, or different segments of the colorectum. For patients with SCRC localized in separate segments, multisegmental resection and anastomosis are often selected for treatment. Compared to conventional surgery, multisegmental resection is less common and more difficult. Selection of the optimal surgical method to promote rapid recovery in patients with SCRC involving separate segments still requires further study.

Previous studies have shown the safety and advantages of laparoscopic surgery in treating solitary CRC[1-5]. However, to date, there are few comparisons of the application of laparoscopic multisegmental resection and anastomosis (LMRA) and open multisegmental resection and anastomosis (OMRA) for SCRC. Therefore, the safety and efficacy of LMRA are not adequately understood and require further evaluation.

To determine the efficacy and safety of LMRA in patients with SCRC involving separate segments, a retrospective two-institution investigation was performed to compare the short-term surgical results, 5-year overall survival (OS) rate, as well as the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate of patients receiving LMRA and OMRA.

Patients with SCRC who underwent surgery between January 2010 and December 2021 at the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the Peking University First Hospital were included. Multiple CRC lesions were diagnosed following published guidelines[6].

The following types of patients were included: (1) SCRC patients with pathological confirmation of lesions as primary adenocarcinoma; (2) SCRC patients with one lesion in the right hemicolon and the others located in the sigmoid colon or rectum; and (3) patients receiving right hemicolectomy as well as anterior resection of the rectum or right hemicolectomy and sigmoid colectomy. The following categories of patients were excluded: (1) Those with familial adenomatous polyposis, ulcerative colitis, hereditary nonpolyposis CRC, or Lynch syndrome; (2) patients with SCRC involving the same segment; (3) patients with SCRC involving adjacent segments; (4) those receiving Hartmann’s procedure or abdominal perineal resection; (5) those receiving subtotal colectomy, total colectomy, or proctocolectomy with ileoanal anastomosis; and (6) SCRC patients with distant metastasis. The selected patients were included in the LMRA and OMRA groups based on the surgical method. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

The following clinicopathological data were collected: Age, gender, abdominal surgery history, concomitant diseases, preoperative chemotherapy, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status level, surgical approach (laparoscopic or open), operative time, volume of blood loss (mL), postoperative first exhaust time (d), time to first liquid diet (d), postoperative hospital stay (d), postoperative complications, classification of complications, tumor size (cm), tumor differentiation status, N stage, T stage and TNM stage, total number of positive lymph nodes (LNs), and number of LNs dissected. Pathological staging was evaluated using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8th ed.) staging system. The Clavien-Dindo (CD) system[7] was employed to grade postoperative complications.

Patients were followed up through telephone calls or outpatient examination. The following time frame was chosen: every 3 mo in the first 2 years following surgery, every 6 mo at 3–5 years following surgery, and then yearly 5 years after surgery. Follow-up assessment included physical examination, determination of serum tumor marker levels, CT scans of the abdomen, chest, and pelvic area, and colonoscopy.

The Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables; Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was employed to create survival curves. Survival differences were compared between the groups by the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to conduct univariate and multivariate prognostic analyses. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 26.0 from IBM (Armonk, NY, United States) was used for statistical determinations.

From January 2010 to December 2021, 605 SCRC patients underwent surgical treatment at the above-mentioned insti

Clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. As noted in this table, the groups did not differ significantly in age, gender, abdominal surgery history, concomitant diseases, preoperative chemotherapy, CA19-9 and CEA levels, ASA class, postoperative chemotherapy, tumor size, tumor differentiation status, N stage, T stage, and TNM stage.

| Variable | OMRA group, n = 41 | LMRA group, n = 68 | P value |

| Age (yr) | |||

| ≤ 65 | 24 (58.5) | 31 (45.6) | 0.190 |

| > 65 | 17 (41.5) | 37 (54.4) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 14 (34.1) | 26 (38.2) | 0.668 |

| Male | 27 (65.9) | 42 (61.8) | |

| ASA physical status | 0.058 | ||

| I-II | 33 (80.5) | 63 (92.6) | |

| III | 8 (19.5) | 5 (7.4) | |

| Concomitant diseases | |||

| No | 19 (46.3) | 29 (42.6) | 0.707 |

| Yes | 22 (53.7) | 39 (57.4) | |

| History of abdominal surgery | |||

| No | 30 (73.2) | 56 (82.4) | 0.255 |

| Yes | 11 (26.8) | 12 (17.6) | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | |||

| No | 39 (95.1) | 68 (100) | 0.139 |

| Yes | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Tumor size1, cm | |||

| ≤ 5 | 20 (50.0) | 40 (58.8) | 0.373 |

| > 5 | 20 (50.0) | 28 (41.2) | |

| Tumor differentiation | |||

| Well-moderate | 24 (58.5) | 32 (47.1) | 0.245 |

| Poor | 17 (41.5) | 36 (52.9) | |

| pT stage | |||

| T1-T2 | 2 (4.9) | 7 (10.3) | 0.525 |

| T3-T4 | 39 (95.1) | 61 (89.7) | |

| pN stage | |||

| N0 | 16 (39.0) | 25 (36.8) | 0.915 |

| N1 | 19 (46.3) | 31 (45.6) | |

| N2 | 6 (14.6) | 12 (17.6) | |

| Stage | |||

| I | 1 (2.4) | 6 (8.8) | 0.338 |

| II | 15 (36.6) | 19 (27.9) | |

| III | 25 (61.0) | 43 (63.2) | |

| CEA | |||

| ≤ 5 | 19 (46.3) | 31 (45.6) | 0.929 |

| > 5 | 13 (31.7) | 20 (29.4) | |

| Unknown | 9 (22.0) | 17 (25.0) | |

| CA199 | |||

| ≤ 37 | 28 (68.3) | 42 (61.8) | 0.696 |

| > 37 | 3 (7.3) | 9 (13.2) | |

| Unknown | 10 (24.4) | 17 (25.0) | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |||

| No | 20 (48.8) | 30 (44.1) | 0.636 |

| Yes | 21 (51.2) | 38 (55.9) |

Table 2 presents the surgical outcomes of both groups. LMRA patients showed markedly less intraoperative blood loss than OMRA patients (100 vs 200 mL, P = 0.006). The LMRA group showed a significantly shorter postoperative first exhaust time (2 vs 3 d, P = 0.001), postoperative first fluid intake time (3 vs 4 d, P = 0.012), and postoperative hospital stay (9 vs 12 d, P = 0.002) than the OMRA group. The incidence of total postoperative complications (CD grade ≥ II) was 2.9% in the LMRA group; this percentage was markedly lower than the value (17.1%) recorded for the OMRA group (P = 0.025). Furthermore, LMRA patients had a lower incidence of anastomotic leakage than OMRA patients; however, the difference was nonsignificant (2.9% vs 7.3%, P = 0.558). The mean number of LNs dissected was significantly greater in LMRA patients as compared to OMRA patients (45.2 vs 37.3, P = 0.020). However, there were no significant differences in operating time, mortality rate, and number of positive LNs between the two groups.

| Variable | OMRA group, n = 41 | LMRA group, n = 68 | P value |

| Operative time (min) | 253.0 ± 101.9 | 274.0 ± 83.4 | 0.244 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 200 (30-600) | 100 (20-600) | 0.006 |

| Time to first exhaust (d) | 3 (1-6) | 2 (1-4) | 0.001 |

| Time to first liquid diets (d) | 4 (2-9) | 3 (2-6) | 0.012 |

| Postoperative complications (Grade Ⅱ-V) | 7 (17.1) | 2 (2.9) | 0.025 |

| Ileus | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.139 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3 (7.3) | 2 (2.9) | 0.558 |

| Cerebral infarction | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.376 |

| Abdominal incision infection | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.376 |

| No. of retrieved lymph nodes | 37.3 ± 17.1 | 45.2 ± 16.8 | 0.020 |

| No. of positive lymph nodes | 1 (0-13) | 1 (0-15) | 0.542 |

| Mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, median, range, days | 12 (7-34) | 9 (3-30) | 0.002 |

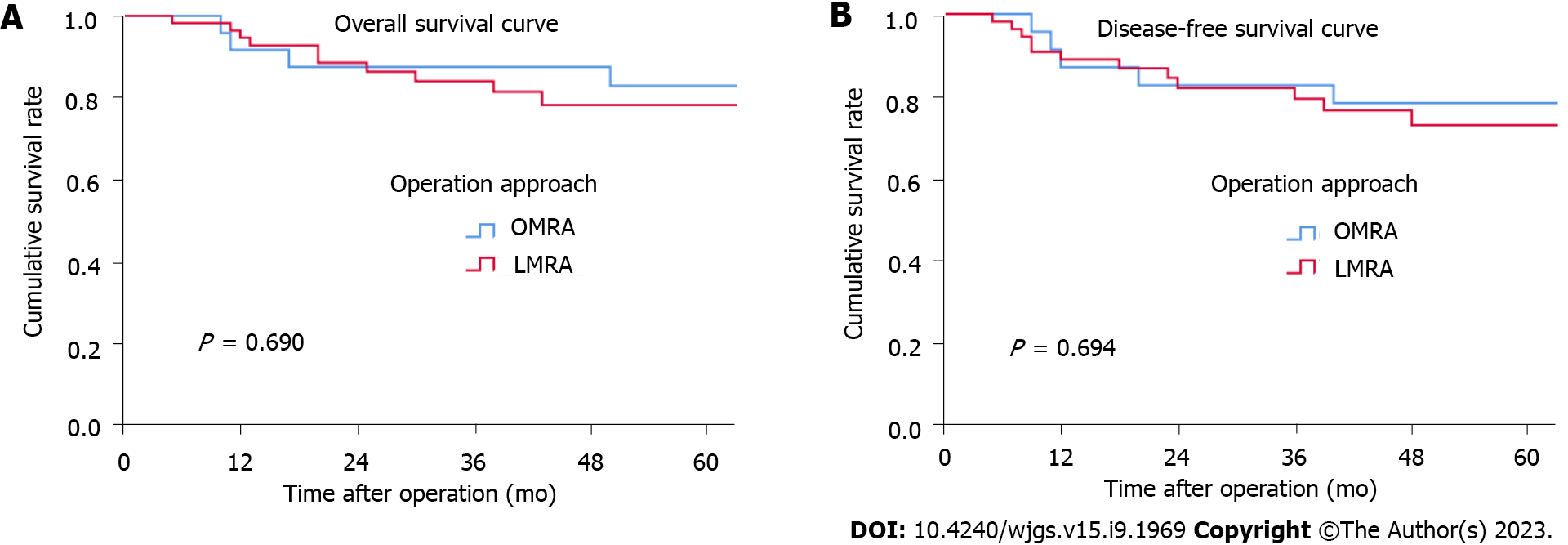

The median follow-up period was 53.5 mo for all patients. OMRA patients had 3-year and 5-year OS rates of 87.5% and 82.9%, respectively; these rates for LMRA patients were 84% and 78.2%, respectively. Additionally, the 3-year and 5-year DFS rates for OMRA patients were 82.6% and 78.3%, respectively; these rates for LMRA patients were 79.3% and 72.8%, respectively. Both groups showed no significant differences in OS (P = 0.690) and DFS (P = 0.694) rates (Figure 1). According to the multivariate prognostic analysis, N stage was an independent prognostic factor for OS [hazard ratio (HR) = 10.161, P = 0.026] and DFS (HR = 13.017, P = 0.013) (Table 3).

| Variable | Overall survival | Disease-free survival | ||||||

| Univariable analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariable analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (> 65/≤ 65 yr) | 2.830 (0.983-8.150) | 0.054 | 2.378 (0.793-7.128) | 0.122 | 2.048 (0.779-5.384) | 0.146 | 1.869 (0.674-5.188) | 0.230 |

| Gender (male/female) | 1.051 (0.382-2.894) | 0.923 | 1.180 (0.436-3.191) | 0.744 | ||||

| CEA level (> 5/≤ 5) | 1.278 (0.389-4.198) | 0.686 | 1.098 (0.348-3.465) | 0.873 | ||||

| CA19-9 level (> 37/≤ 37) | 1.951 (0.506-7.521) | 0.332 | 1.304 (0.285-5.958) | 0.732 | ||||

| ASA physical status (III/I-II) | 2.565 (0.817-8.050) | 0.106 | 2.280 (0.655-7.940) | 0.195 | ||||

| Tumor differentiation (poor/well- moderate) | 0.918 (0.340-2.478) | 0.866 | 1.119 (0.431-2.906) | 0.817 | ||||

| Tumor size (> 5/≤ 5 cm) | 1.058 (0.383-2.920) | 0.913 | 0.863 (0.328-2.269) | 0.764 | ||||

| T stage (T3-T4/T1-T2) | 0.994 (0.130-7.627) | 0.994 | 1.302 (0.172-9.854) | 0.798 | ||||

| N stage (N1-N2/N0) | 11.266 (1.487-85.384) | 0.019 | 10.161 (1.327-77.790) | 0.026 | 13.414 (1.775-101.359) | 0.012 | 13.107 (1.719-99.925) | 0.013 |

| Operative approach (LMRA/OMRA) | 1.240 (0.426-3.611) | 0.693 | 0.834 (0.274-2.534) | 0.749 | 1.233 (0.432-3.516) | 0.695 | 0.812 (0.269-2.454) | 0.712 |

SCRC involving separate segments is a relatively rare type of CRC. Surgeons can choose two regional resections and anastomoses for preserving the left hemicolon or extensive resection, for example, total colectomy, subtotal colectomy, or proctocolectomy with ileoanal anastomosis. Which is the best treatment option is still unresolved. Lee et al[8] retro

Following advances in laparoscopic techniques, several studies have confirmed that laparoscopic radical resection of CRC is safe and reliable; moreover, it can achieve the same curative effect as open surgery[10-14] and offers the advantages of minimally invasive surgery, such as small incision, mild postoperative pain, and rapid recovery[15,16]. However, unlike conventional CRC surgery, surgical treatment of SCRC with multisegmental resection is more difficult as more anastomoses are required. Presently, there are limited reports on the differences between laparoscopic and open surgical approach for SCRC involving separate segments. These studies are limited to single-center investigations with few patients and are mainly focused on the analysis of short-term efficacy; consequently, they lack a comparison of long-term prognosis[17,18]. Here, we studied patients from two institutions with SCRC located in separate segments. These patients underwent either LMRA or OMRA as curative surgery. We found that intraoperative blood loss together with postoperative parameters such as postoperative first exhaust time, postoperative first fluid intake time, the incidence of postoperative complications, and postoperative hospital stay were less in LMRA patients when compared with those in OMRA patients. Furthermore, LMRA patients had more LNs dissected than OMRA patients, while the prognosis for both groups was similar. To our knowledge, this study includes the largest sample size for comparing LMRA and OMRA approaches with regard to short-term efficacy as well as long-term results.

Intraoperative blood loss and the incidence of postoperative complications are critical parameters for evaluating whether a surgical procedure is safe. Previous studies have confirmed that laparoscopic surgery has more advantages than open surgery for solitary CRC in terms of less intraoperative blood loss[19-22], reduced postoperative oral intake time[21,22], and shorter postoperative hospital stay[21-25]. Moreover, previous single-center, small-sample studies have reached the same conclusion for patients with SCRC involving different segments. Takatsu et al[17] compared the short-term efficacy of LMRA and OMRA in 42 patients with SCRC located in different segments; the authors noted that postoperative hospital stay and intraoperative blood loss were significantly decreased in the laparoscopic group as compared to the open surgery group. Nozawa et al[18] performed a single-center study of 25 patients with SCRC; the authors found that the laparoscopic group showed less intraoperative blood loss than the open surgery group. Here, we analyzed the surgical results of 109 patients with SCRC located in separate segments and found significantly less intraoperative blood loss in LMRA patients than in OMRA patients. Moreover, the total postoperative complication as well as hospital stay were remarkably better in LMRA patients. Furthermore, the operating time was not significantly increased in LMRA patients.

The number of dissected LNs is another crucial factor in evaluating radical surgery of CRC. In accordance with the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the number of dissected LNs should be 12 or more after radical surgery of CRC. If the number of dissected LNs is small, the final staging will be affected. For SCRC located in separate segments, the number of dissected LNs is another vital indicator in evaluating surgical quality. Laparoscopy enables magnification of the operative field; hence, the dissection of LNs by laparoscopy is more precise than that by open surgery. A significantly higher number of LNs have been dissected by laparoscopy than by traditional open surgery[17]. The present study revealed that the average number of LNs dissected in LMRA patients was significantly more than that in OMRA patients; this finding was in agreement with the result of Takatsu et al[17]. However, both groups did not significantly differ in the number of positive LNs.

According to several studies, both laparoscopic and open surgeries have similar oncological results[26-30]. However, for SCRC located in separate segments, comparative studies on the long-term efficacy of LMRA and OMRA are presently inadequate. In our study, the 5-year OS rates of LMRA and OMRA patients were 78.2% and 82.9%, respectively, while the 5-year DFS rates of LMRA and OMRA patients were 72.8% and 78.3%, respectively. Both groups did not markedly differ in long-term prognosis. We further performed a multivariate prognostic analysis and found that the N stage was the sole independent prognostic factor that affected DFS and OS.

There are a few limitations in this research. First, selection bias probably existed due to the study’s retrospective nature. Second, some patients’ clinical data were incomplete, such as the time of first ambulation and postoperative pain score; thus, we could not compare and analyze the differences between open and laparoscopic approaches with regard to these aspects. Third, as the incidence of SCRC located in separate segments is low, although the sample size in this study is the largest thus far, the number of patients included in the analysis is still small. Therefore, multicenter prospective studies are needed in the future to confirm the advantages of LMRA.

LMRA is safe and feasible for SCRC located in separate segments; moreover, it has the benefits of less bleeding, rapid recovery, shorter postoperative hospital stay, reduced complications, a greater total number of LNs dissected and achieves the same long-term oncological outcomes as OMRA.

Limited studies have focused on the differences between laparoscopic multisegmental resection and anastomosis (LMRA) and open multisegmental resection and anastomosis (OMRA) for synchronous colorectal cancer (SCRC) involving separate segments. Therefore, more studies on the safety and efficacy of LMRA are needed.

To assess the efficacy and safety of LMRA in patients with SCRC involving separate segments.

The objectives of this study were to compare the short-term efficacy and long-term oncological consequences of OMRA as well as LMRA for SCRC located in separate segments.

A retrospective two-institution investigation was performed in 109 patients who received right hemicolectomy together with anterior resection of the rectum or right hemicolectomy and sigmoid colectomy. The OMRA and LMRA groups included 41 and 68 patients, respectively. The clinicopathological characteristics and surgical results were compared between the groups, and the Cox proportional hazards model was used to conduct univariate and multivariate prognostic analyses.

LMRA patients showed significantly shorter postoperative first exhaust time, postoperative first fluid intake time, and postoperative hospital stay than OMRA patients. Intraoperative blood loss, and the incidence of total postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo grade: ≥ II) were markedly less in the LMRA group. The mean number of lymph nodes dissected was significantly higher in the LMRA group. Prognostic analysis showed that N stage was the independent prognostic factor for overall survival and disease-free survival.

On the basis of this study, we conclude that LMRA has some short-term advantages compared with OMRA, and is safe and feasible for patients with SCRC located in separate segments.

Future multicenter prospective studies are needed to further confirm the advantages of LMRA.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Diez-Alonso M, Spain; Gad EH, Egypt S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Yang X, Zhong ME, Xiao Y, Zhang GN, Xu L, Lu J, Lin G, Qiu H, Wu B. Laparoscopic vs open resection of pT4 colon cancer: a propensity score analysis of 94 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:O316-O325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moon SY, Kim S, Lee SY, Han EC, Kang SB, Jeong SY, Park KJ, Oh JH; SEoul COlorectal Group (SECOG). Laparoscopic surgery for patients with colorectal cancer produces better short-term outcomes with similar survival outcomes in elderly patients compared to open surgery. Cancer Med. 2016;5:1047-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tan KL, Deng HJ, Chen ZQ, Mou TY, Liu H, Xie RS, Liang XM, Fan XH, Li GX. Survival outcomes following laparoscopic vs open surgery for non-metastatic rectal cancer: a two-center cohort study with propensity score matching. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2020;8:319-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li Z, Zou Z, Lang Z, Sun Y, Zhang X, Dai M, Mao S, Han Z. Laparoscopic versus open radical resection for transverse colon cancer: evidence from multi-center databases. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:1435-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang ZF, Wu DQ, Wang JJ, Lv ZJ, Li Y. Short- and long-term outcomes following laparoscopic vs open surgery for pathological T4 colorectal cancer: 10 years of experience in a single center. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:76-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Warren S, Gates O. Multiple primary malignant tumors: a survey of the literature and a statistical study. Am J Cancer. 1932;16:1358-1414. |

| 7. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24842] [Article Influence: 1183.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee BC, Yu CS, Kim J, Lee JL, Kim CW, Yoon YS, Park IJ, Lim SB, Kim JC. Clinicopathological features and surgical options for synchronous colorectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | You YN, Chua HK, Nelson H, Hassan I, Barnes SA, Harrington J. Segmental vs. extended colectomy: measurable differences in morbidity, function, and quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1036-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Völkel V, Draeger T, Schnitzbauer V, Gerken M, Benz S, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Fürst A. Surgical treatment of rectal cancer patients aged 80 years and older-a German nationwide analysis comparing short- and long-term survival after laparoscopic and open tumor resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:1607-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hida K, Okamura R, Sakai Y, Konishi T, Akagi T, Yamaguchi T, Akiyoshi T, Fukuda M, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto M, Nishigori T, Kawada K, Hasegawa S, Morita S, Watanabe M; Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. Open versus Laparoscopic Surgery for Advanced Low Rectal Cancer: A Large, Multicenter, Propensity Score Matched Cohort Study in Japan. Ann Surg. 2018;268:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujii S, Ishibe A, Ota M, Yamagishi S, Watanabe J, Suwa Y, Kunisaki C, Endo I. Long-term results of a randomized study comparing open surgery and laparoscopic surgery in elderly colorectal cancer patients (Eld Lap study). Surg Endosc. 2021;35:5686-5697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Quintana JM, Antón-Ladisla A, González N, Lázaro S, Baré M, Fernández de Larrea N, Redondo M, Briones E, Escobar A, Sarasqueta C, García-Gutierrez S; REDISSEC-CARESS/CCR group. Outcomes of open versus laparoscopic surgery in patients with colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1344-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Creavin B, Kelly ME, Ryan ÉJ, Ryan OK, Winter DC. Oncological outcomes of laparoscopic versus open rectal cancer resections: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Br J Surg. 2021;108:469-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sun JL, Xing SY. Short-term outcome of laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery on colon carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Math Biosci Eng. 2019;16:4645-4659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Huang YM, Lee YW, Huang YJ, Wei PL. Comparison of clinical outcomes between laparoscopic and open surgery for left-sided colon cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Takatsu Y, Akiyoshi T, Nagata J, Nagasaki T, Konishi T, Fujimoto Y, Nagayama S, Fukunaga Y, Ueno M. Surgery for synchronous colorectal cancers with double colonic anastomoses: A comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2015;8:429-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nozawa H, Ishihara S, Murono K, Yasuda K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Kawai K, Yamaguchi H, Watanabe T. Laparoscopy-assisted versus open surgery for multiple colorectal cancers with two anastomoses: a cohort study. Springerplus. 2016;5:287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sasi S, Kammar P, Masillamany S, De' Souza A, Engineer R, Ostwal V, Saklani A. Laparoscopic versus open resection in locally advanced rectal cancers: a propensity matched analysis of oncological and short-term outcomes. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:2894-2903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou S, Wang X, Zhao C, Liu Q, Zhou H, Zheng Z, Zhou Z, Liang J. Laparoscopic vs open colorectal cancer surgery in elderly patients: short- and long-term outcomes and predictors for overall and disease-free survival. BMC Surg. 2019;19:137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nishikawa T, Ishihara S, Hata K, Murono K, Yasuda K, Otani K, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Kawai K, Nozawa H, Yamaguchi H, Watanabe T. Short-term outcomes of open versus laparoscopic surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5550-5557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dai J, Yu Z. Comparison of Clinical Efficacy and Complications Between Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery for Low Rectal Cancer. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2019;22:179-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goto K, Watanabe J, Suwa Y, Nakagawa K, Suwa H, Ozawa M, Ishibe A, Ota M, Kunisaki C, Endo I. A multicenter, propensity score-matched cohort study about short-term and long-term outcomes after laparoscopic versus open surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:1287-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jiang WZ, Xu JM, Xing JD, Qiu HZ, Wang ZQ, Kang L, Deng HJ, Chen WP, Zhang QT, Du XH, Yang CK, Guo YC, Zhong M, Ye K, You J, Xu DB, Li XX, Xiong ZG, Tao KX, Ding KF, Zang WD, Feng Y, Pan ZZ, Wu AW, Huang F, Huang Y, Wei Y, Su XQ, Chi P; LASRE trial investigators. Short-term Outcomes of Laparoscopy-Assisted vs Open Surgery for Patients With Low Rectal Cancer: The LASRE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1607-1615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, Fürst A, Lacy AM, Hop WC, Bonjer HJ; COlorectal cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection II (COLOR II) Study Group. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1030] [Cited by in RCA: 1214] [Article Influence: 101.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pedrazzani C, Turri G, Park SY, Hida K, Fukui Y, Crippa J, Ferrari G, Origi M, Spolverato G, Zuin M, Bae SU, Baek SK, Costanzi A, Maggioni D, Son GM, Scala A, Rockall T, Larson DW, Guglielmi A, Choi GS. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for left flexure colon cancer: A propensity score matched analysis from an international cohort. Colorectal Dis. 2022;24:177-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Son IT, Kim JY, Kim MJ, Kim BC, Kang BM, Kim JW. Clinical and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic versus open surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26:2237-2245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu ZH, Wang N, Wang FQ, Dong Q, Ding J. Oncological outcomes of laparoscopic versus open surgery in pT4 colon cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;56:221-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Matsumoto A, Shinohara H, Suzuki H. Laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with transverse colon cancer: short-term and oncological outcomes. BJS Open. 2021;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pla-Martí V, Martín-Arévalo J, Moro-Valdezate D, García-Botello S, Pérez-Santiago L, Lapeña-Rodríguez M, Bauzá-Collado M, Huerta M, Roselló-Keränen S, Espí-Macías A. Prognostic implications of surgical specimen quality on the oncological outcomes of open and laparoscopic surgery in mid and low rectal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:2759-2767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |