Published online Aug 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1825

Peer-review started: May 2, 2023

First decision: June 16, 2023

Revised: June 20, 2023

Accepted: July 11, 2023

Article in press: July 11, 2023

Published online: August 27, 2023

Processing time: 114 Days and 18.5 Hours

Embryonic hepatic artery anatomy simplifies its identification during liver transplantation. Injuries to the donor hepatic artery can cause complications in this process. The hepatic artery's complex anatomy in adults makes this step challenging; however, during embryonic development, the artery and its branches have a simpler relationship. By restoring the embryonic hepatic artery anatomy, surgeons can reduce the risk of damage and increase the procedure's success rate. This approach can lead to improved patient outcomes and lower complication rates.

In this study, we report a case of donor liver preparation using a donor hepatic artery preparation based on human embryology. During the preparation of the hepatic artery, we restored the anatomy of the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and their branches to the state of the embryo at 5 wk. This allowed us to dissect the variant hepatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery and left gastric artery during the operation. After implanting the donor liver into the recipient, we observed normal blood flow in the donor hepatic artery, main hepatic artery, and variant hepatic artery, without any leakage.

Donor hepatic artery preparation based on human embryology can help reduce the incidence of donor hepatic artery injuries during liver transplantation.

Core Tip: The repair of the donor hepatic artery is a very important step in liver transplantation. In the liver with abnormal arterial anatomy, the incidence of hepatic artery injury is very high. We invented a method of donor hepatic artery repair based on human embryology, which is a method of restoring the artery to the embryonic anatomy, greatly reducing the damage probability of the mutated hepatic artery.

- Citation: Zhang HZ, Lu JH, Shi ZY, Guo YR, Shao WH, Meng FX, Zhang R, Zhang AH, Xu J. Donor hepatic artery reconstruction based on human embryology: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(8): 1825-1830

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i8/1825.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1825

Liver transplantation is the only definitive treatment for end-stage liver disease[1]. However, many patients die while waiting for a liver source, and the shortage of liver sources is the greatest challenge facing liver transplantation[2]. Therefore, it is important to ensure that organ anatomy is not injured during liver transplantation[3].

Liver transplantation consists of several steps, including donor liver acquisition, donor liver preparation, diseased liver resection, and donor liver implantation. The purpose of donor liver preparation is to carefully dissect the blood vessels and biliary tract of the liver, remove excess perihepatic tissue, and reduce postoperative rejection, which is an important factor in determining the success or failure of transplantation.

The common hepatic artery is one of the main arteries that supply the liver, gallbladder, lesser omentum, and gastroduodenum. Its branches and variations are complex[4,5]. Choi et al[6] retrospectively studied the hepatic artery imaging data of 5625 patients and found that the overall incidence rate of abnormal hepatic arteries was 27.41%, with the incidence rate of the aberrant right hepatic artery (aRHA) being 15.63%, and the incidence rate of the aberrant left hepatic artery (aLHA) being 16.32%. Additionally, the incidence rate of aRHA combined with aLHA was 4.53%. There are many classification systems for hepatic artery anatomy, among which Michel’s classification is the most frequently used[7-12]. Because the branches of the intrahepatic artery are not dissected during donor liver preparation, and angiography is not routinely performed, it is not always possible to determine whether the variant hepatic artery is a substitute or an accessory hepatic artery (accessory replacement). Therefore, once a hepatic artery variation is identified while pruning the hepatic artery, dissection and protection are required. Lack of experience and awareness can easily lead to damage to anatomical variations in the hepatic artery[13].

The incidence of hepatic artery injury has significantly increased during the preparation of donor livers with abnormal hepatic artery anatomy[14]. Accurate identification and correct treatment of the variant hepatic artery during surgery are essential to ensure the integrity of the donor hepatic artery. This is the basis for good postoperative recovery of liver function and reduction of postoperative hepatic artery complications.

Postoperative hepatic artery complications are critical factors that can significantly impact the prognosis of liver transplantation[6-8]. Studies have reported that the incidence of hepatic artery complications ranges from 3% to 9%. Hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) is the most common and serious vascular complication of liver transplantation, often the leading cause of primary dysfunction and graft loss[11]. Arterial remodeling is necessary when an artery is injured and some studies have suggested that it may increase the risk of HAT. Surgical injury of the donor hepatic artery may increase the incidence of HAT, graft dysfunction, and graft loss, rendering the donor liver unsuitable for transplantation[14].

The commonly used methods of trimming hepatic arteries are as follows: The superior mesenteric artery is dissected within 2-3 cm of the initial part and the right replacement or accessory hepatic artery are searched. Simultaneously, the hepatogastric ligaments are examined for the left replacement or accessory hepatic artery, which originate from the left gastric artery to the liver. Currently, the process of preparing the donor's liver is based on the normal physiological anatomy, which may lead to arterial damage, especially in cases of variant hepatic arteries, where the abnormal shape of the artery and the surgeon's lack of experience can lead to injury. These complications can significantly impact clinical practice, highlighting the need for improved techniques. In this case report, we describe a method of donor hepatic artery preparation based on human embryology, which reduces the risk of arterial damage, especially in variant arteries.

The liver donor was a 43-year-old man who had fallen into a coma from a traumatic accident.

The liver donor was diagnosed with brain stem injury, and the patient was transferred to our hospital six hours after the accident for further treatment.

The liver donor was physically fit.

His family history was noncontributory.

Liver donors go into coma, their nerve reflexes disappear. No bruising or ecchymosis was observed in the abdomen.

Laboratory examinations including routine blood and blood coagulation, liver function, biochemistry, tumor markers, and infection markers revealed no abnormalities.

Head computed tomography scan indicated skull fracture, brain contusion and laceration, intracranial hematoma, brain edema, ventricle compression and displacement, midline structure displacement, abdominal color ultrasound indicated no traumatic injury and benign and malignant diseases in liver.

Based on the liver donor's symptoms, examination and imaging findings, the preliminary diagnosis was brain stem injury. And he didn't have any acute or chronic damage to his liver.

Following organ retrieval, the liver was refrigerated and transported in an organ storage box. The warm ischemia time of the liver was 3 min, the cold ischemia time was 4 h, and the mass of the liver after preparation was 1427 g. Upon arrival in the operating room, the liver was completely immersed in the University of Wisconsin (UW) solution at 0-4℃ for preparation. The superior and inferior hepatic vena cava and biliary tract were then prepared sequentially.

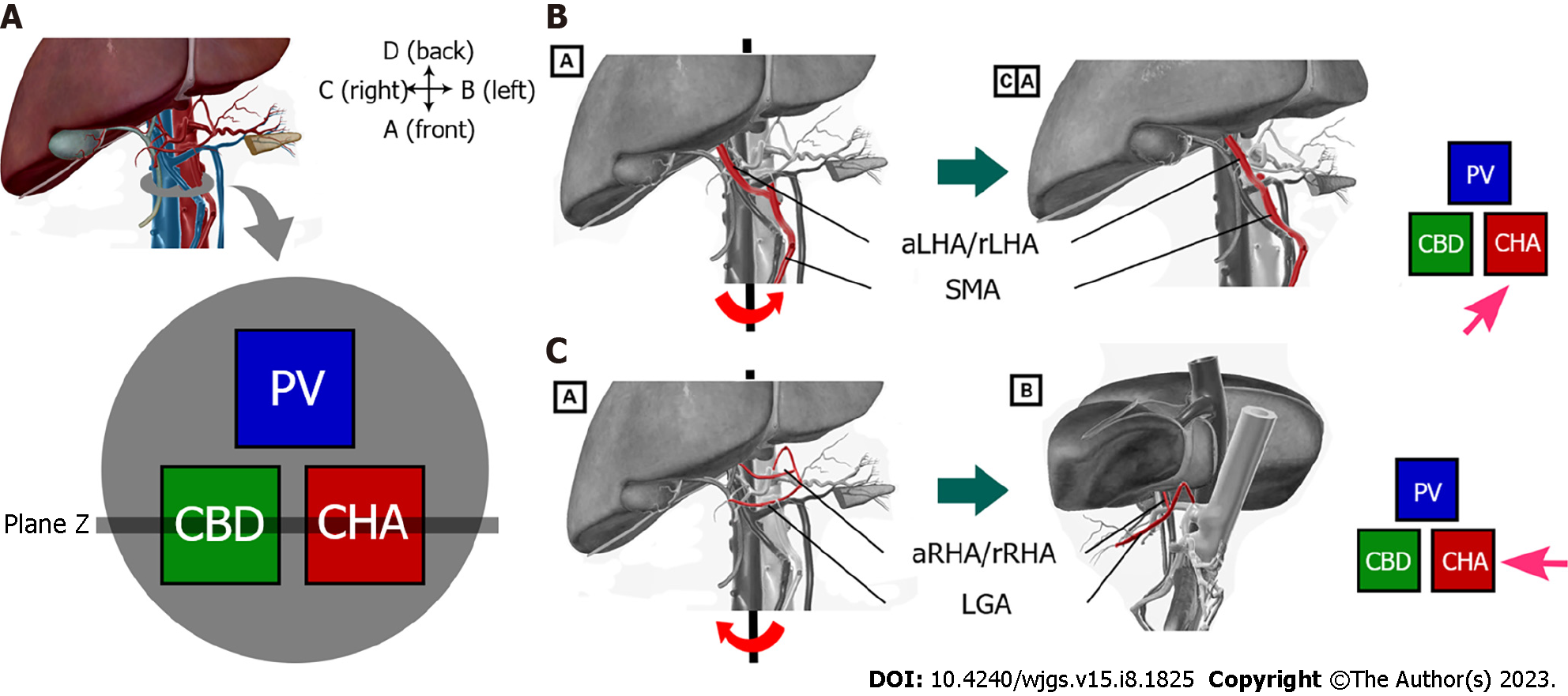

In order to avoid the damage of the potentially mutated hepatic artery, we decided to prepare the donor hepatic artery using a new hepatic artery preparation protocol. In the normal anatomical position, the gastroduodenal artery was identified and dissected until it reached the proper hepatic artery, which was set as the endpoint for the arterial preparation. Next, the liver was rotated counterclockwise by approximately 45° from its normal position, and the superior mesenteric artery was dissected from the severed end. During dissection, it was noted that a variant of the right hepatic artery was present within 5 cm of the root of the superior mesenteric artery, which was then carefully dissociated (Figure 1B). The liver was then rotated clockwise by approximately 90° from the normal anatomical position, beginning at the end of the splenic artery. The splenic artery was dissected and prepared up to its origin at the celiac trunk, followed by the dissection and preparation of the left gastric artery from its distal end. During this dissection, it was noted that a variant of the left hepatic artery was located directly above the left gastric artery and was dissociated carefully (Figure 1C). Finally, the liver was restored to its normal anatomical position, and the proper hepatic artery was dissected and prepared up to its bifurcation into the hepatic artery proper and the gastroduodenal artery. After preparing the portal vein and ligating any possible bleeding sites, excess tissue was removed, and the liver was re-immersed in a 0-4℃ UW solution.

During the liver transplantation procedure, the right accessory hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery of the donor liver was anastomosed end to end with the gastroduodenal artery of the donor liver, and the left gastric artery was ligation after sending out the left accessory hepatic artery. This treatment ensured the blood supply of the left hepatic artery, right hepatic artery, left accessory hepatic artery, and right accessory hepatic artery simultaneously. Once implanted into the recipient, the blood flow at the proximal end of the anastomosis was opened, and the anomalous hepatic artery was filled well without any evidence of arterial wall leakage. Intraoperative color Doppler ultrasound confirmed normal blood flow in the intrahepatic arteries, with a flow velocity of 43 cm/s [resistive index (RI):0.42] in the left hepatic artery, and a flow rate of 55 cm/s (RI: 0.54) in the right hepatic artery.

The preparation of the donor hepatic artery is a critical step in liver transplantation, and the incidence of hepatic artery injury is significantly higher in livers with abnormal arterial anatomy[6]. The traditional method of donor hepatic artery preparation is based on normal anatomy; however, in cases of variant hepatic artery anatomy, the preparation process can easily damage the surrounding normal tissues, such as arteries, common bile ducts, and portal veins. To address this limitation, we have developed a novel method for donor hepatic artery preparation based on human embryology. This approach involves preparing the artery to restore it to its embryonic anatomy, which significantly reduces the probability of injury to the variant hepatic artery.

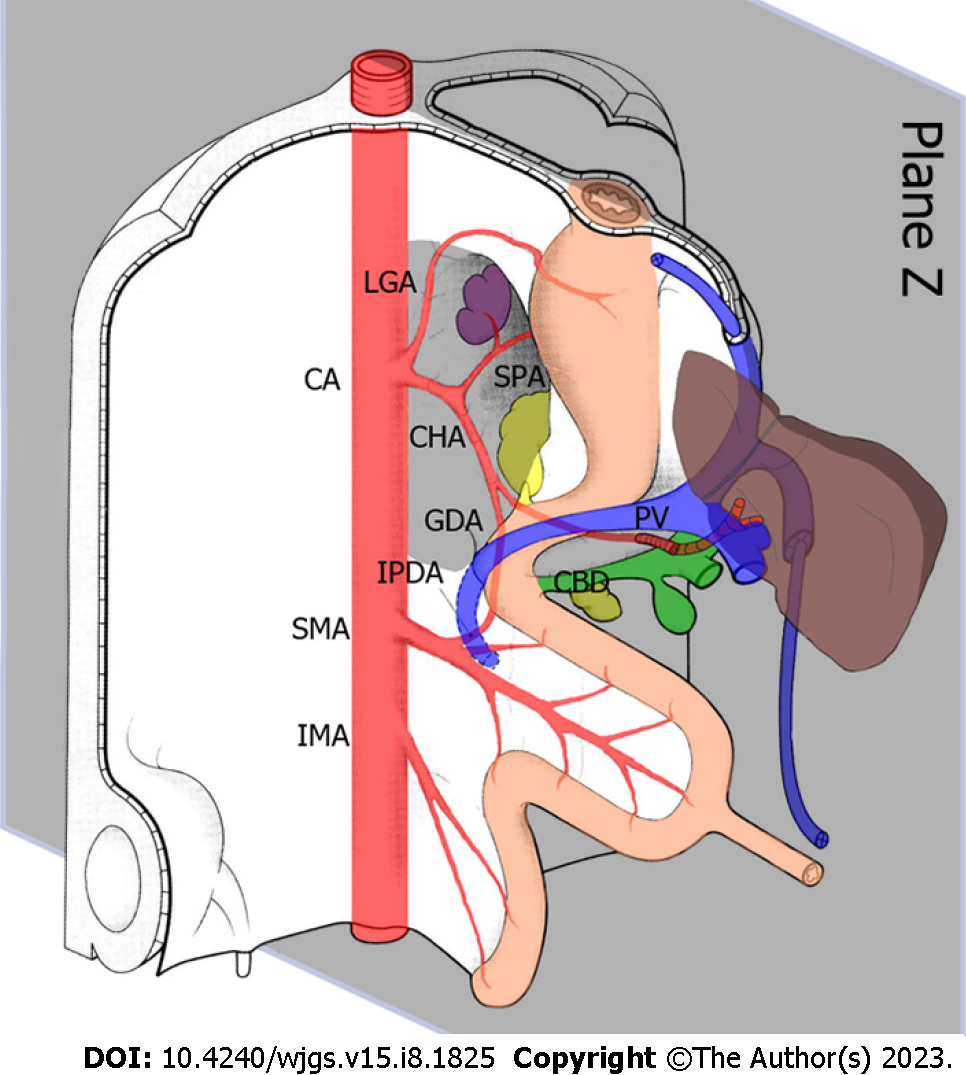

During fetal development, paired ventral splanchnic arteries from each dorsal aorta supply the primitive gut and its derivatives. Later in development, these vessels are represented by three arterial trunks: the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery, which supply the foregut, midgut, and hindgut, respectively[15]. Approximately 5 wk after conception, the spleen, pancreas, stomach, and liver are situated in the sagittal plane of the embryo, and the arteries are nearly in the same two-dimensional plane, resulting in a relatively simple anatomy. However, in the 6th week after conception, the stomach, pancreas, spleen, and liver all begin to move clockwise to the left, and the blood vessels in the upper abdomen rotate to form a three-dimensional intricate network of blood vessels. The complexity and variation of the upper abdominal vascular system arise from the rotation and fusion of the gastrum during embryonic development.

In normal human anatomy, the hepatic pedicle is a structure within and outside of the first hepatic hilum that runs through the hepatoduodenal ligament. Within the hepatoduodenal ligament, the common bile duct, portal vein, and hepatic artery are positioned in a triangular relationship. The common bile duct was located to the right of the proper hepatic artery and in front of the portal vein (Figure 1A). By adjusting our understanding of the normal anatomy to the embryonic position in the 5th week (before rotation), we can simplify the complex three-dimensional relationship of the vessels into a two-dimensional plane, which greatly simplifies the relationship between the celiac artery and its surrounding tissues, and our understanding of donor hepatic artery preparation. In the anatomical position known as the ‘Z plane’ (Figure 2), variant hepatic arteries can only exist in this two-dimensional plane. Damage to the variant hepatic artery could be avoided by preparing the artery from top to bottom or from bottom to top in the Z-plane.

This case report presents a novel technique based on human embryology for preparing the donor hepatic arteries. This surgical approach has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk of intraoperative injury to both the normal and variant arteries.

Thanks are due to Ming Gao for assistance with the experiments and to Dong-Dong Wu for valuable discussion.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Goja S, India; Mikulic D, Croatia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Zturk NB, Muhammad H, Gurakar M, Aslan A, Gurakar A, Dao D. Liver transplantation in developing countries. Hepatol Forum. 2022;3:103-107. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Bodzin AS, Baker TB. Liver Transplantation Today: Where We Are Now and Where We Are Going. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:1470-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Soliman T, Langer F, Puhalla H, Pokorny H, Grunberger T, Berlakovich GA, Langle F, Muhlbacher F, Steininger R. Parenchymal liver injury in orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69:2079-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Németh K, Deshpande R, Máthé Z, Szuák A, Kiss M, Korom C, Nemeskéri Á, Kóbori L. Extrahepatic arteries of the human liver - anatomical variants and surgical relevancies. Transpl Int. 2015;28:1216-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pérez-Saborido B, Pacheco-Sánchez D, Barrera Rebollo A, Pinto Fuentes P, Asensio Díaz E, Labarga Rodriguez F, Sarmentero Prieto JC, Martínez Díez R, Rodríguez Vielba P, Gonzálo Martín M, Rodríguez López M, de Anta Román A. Incidence of hepatic artery variations in liver transplantation: does it really influence short- and long-term results? Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2606-2608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Choi TW, Chung JW, Kim HC, Lee M, Choi JW, Jae HJ, Hur S. Anatomic Variations of the Hepatic Artery in 5625 Patients. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021;3:e210007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hiatt JR, Gabbay J, Busuttil RW. Surgical anatomy of the hepatic arteries in 1000 cases. Ann Surg. 1994;220:50-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Michels NA. Newer anatomy of the liver and its variant blood supply and collateral circulation. Am J Surg. 1966;112:337-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rong GH, Sindelar WF. Aberrant peripancreatic arterial anatomy. Considerations in performing pancreatectomy for malignant neoplasms. Am Surg. 1987;53:726-729. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Abdullah SS, Mabrut JY, Garbit V, De La Roche E, Olagne E, Rode A, Morin A, Berthezene Y, Baulieux J, Ducerf C. Anatomical variations of the hepatic artery: study of 932 cases in liver transplantation. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Donato P, Coelho P, Rodrigues H, Vigia E, Fernandes J, Caseiro-Alves F, Bernardes A. Normal vascular and biliary hepatic anatomy: 3D demonstration by multidetector CT. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29:575-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yan J, Feng H, Wang H, Yuan F, Yang C, Liang X, Chen W, Wang J. Hepatic artery classification based on three-dimensional CT. Br J Surg. 2020;107:906-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karakoyun R, Romano A, Yao M, Dlugosz R, Ericzon BG, Nowak G. Impact of Hepatic Artery Variations and Reconstructions on the Outcome of Orthotopic Liver Transplantation. World J Surg. 2020;44:1954-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nijkamp DM, Slooff MJ, van der Hilst CS, Ijtsma AJ, de Jong KP, Peeters PM, Porte RJ. Surgical injuries of postmortem donor livers: incidence and impact on outcome after adult liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1365-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Agarwal S, Pangtey B, Vasudeva N. Unusual Variation in the Branching Pattern of the Celiac Trunk and Its Embryological and Clinical Perspective. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:AD05-AD07. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |