Published online Aug 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1808

Peer-review started: April 24, 2023

First decision: June 1, 2023

Revised: June 7, 2023

Accepted: June 27, 2023

Article in press: June 27, 2023

Published online: August 27, 2023

Processing time: 122 Days and 18.9 Hours

Gastric cancer (GC) is a major health concern worldwide. Surgical resection and chemotherapy is the mainstay treatment for gastric carcinoma, however, the optimal approach remains unclear and should be different in each individual. Chemotherapy can be administered both pre- and postoperatively, but a multidisciplinary approach is preferred when possible. This is particularly relevant for locally advanced GC (LAGC), as neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAT) could potentially lead to tumor downsizing thus allowing for a complete resection with curative intent. Even though the recent progress has been impressive, European and International guidelines are still controversial, thus attenuating the need for a more standardized approach in the management of locally advanced cancer.

To investigate the effects of NAT on the overall survival (OS), the disease-free survival (DFS), the morbidity and the mortality of patients with LAGC in comparison to upfront surgery (US).

For this systematic review, a literature search was conducted between November and February 2023 in PubMed, Cochrane Library and clinicaltrials.gov for studies including patients with LAGC. Two independent reviewers conducted the research and extracted the data according to predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses was used to form the search strategy and the study protocol has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews.

Eighteen studies with 4839 patients with LAGC in total were included in our systematic review. Patients were separated into two groups; one receiving NAT before the gastrectomy (NAT group) and the other undergoing upfront surgery (US group). The OS ranged from 41.6% to 74.2% in the NAT group and from 30.9% to 74% in the US group. The DFS was also longer in the NAT group and reached up to 80% in certain patients. The complications related to the chemotherapy or the surgery ranged from 6.4% to 38.1% in the NAT group and from 5% to 40.5% in the US group. Even though in most of the studies the morbidity was lower in the NAT group, a general conclusion could not be drawn as it seems to depend on multiple factors. Finally, regarding the mortality, the reported rate was higher and up to 5.3% in the US group.

NAT could be beneficial for patients with LAGC as it leads to better OS and DFS than the US approach with the same or even lower complication rates. However, patients with different clinicopathological features respond differently to chemotherapy, therefore currently the treatment plan should be individualized in order to achieve optimal results.

Core Tip: Gastric cancer (GC) is a major concern worldwide. According to Globocan there were 1089000 new cases of GC and 768000 GC related deaths worldwide in 2020 with almost twice the prevalence and mortality in males than in females. The highest prevalence is observed in Eastern Asia whereas the lowest in Africa. Gastrectomy is the mainstay approach in patients that can undergo surgery and in recent years with the advances in chemotherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAT) has shown potential for better survival chances. That is particularly relevant in patients with locally advanced GC as NAT could potentially lead to tumor downsizing thus allowing for higher complete resection rate. In our review we compare patients receiving NAT and then undergoing D2 gastrectomy to those undergoing upfront surgery.

- Citation: Fiflis S, Papakonstantinou M, Giakoustidis A, Christodoulidis G, Louri E, Papadopoulos VN, Giakoustidis D. Comparison between upfront surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(8): 1808-1818

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i8/1808.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1808

According to Globocan there were 1089000 new cases of gastric cancer (GC) and 768000 GC related deaths worldwide in 2020 with almost twice the prevalence and mortality in males than in females. The highest prevalence is observed in Eastern Asia whereas the lowest in Africa and the highest mortality rate in Eastern Asia while the lowest in Northern America, Australia and Europe. GC is subcategorized according to Lauren’s classification into intestinal and diffuse subtypes which demonstrate different epidemiology, clinical behavior, chemoresistance, progression and prognosis but there have been no trials or analyses to evaluate whether these two subtypes would potentially benefit more from different treatment modalities[1].

Locally advanced GC (LAGC) is defined as T2 or higher clinical disease, with or without nodal involvement, and surgical resection with an adequate D2-lymphadenectomy is the cornerstone of the medical approach with curative intent alongside with other perioperative treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy[1]. The role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAT) is being rigorously studied as an important treatment regimen that aims to eliminate micrometastasis, downstage tumors and thus prolong OS, DFS and improve recurrence and R0 resection rates. LAGC patients are at high risk of developing distant metastases therefore they should be offered NAT. And patients who undergo surgery without NAT are at high risk of recurrence and should be submitted to adjuvant chemoradiation[2].

Even though NAT is being offered to patients with LAGC in Europe and the United States, the treatment regimens differ between the Western and the Eastern countries. For instance, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is largely administered in the United States, neoadjuvant followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in the United Kingdom and solely postoperative chemotherapy is administered in Korea and Japan according to INT0116 trial, MAGIC trial, ACT-GC trial and CLASSIC respectively[3-6]. In this systematic review we assess the role of NAT in patients undergoing surgery for LAGC. We aim to investigate the approach that offers the highest overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates.

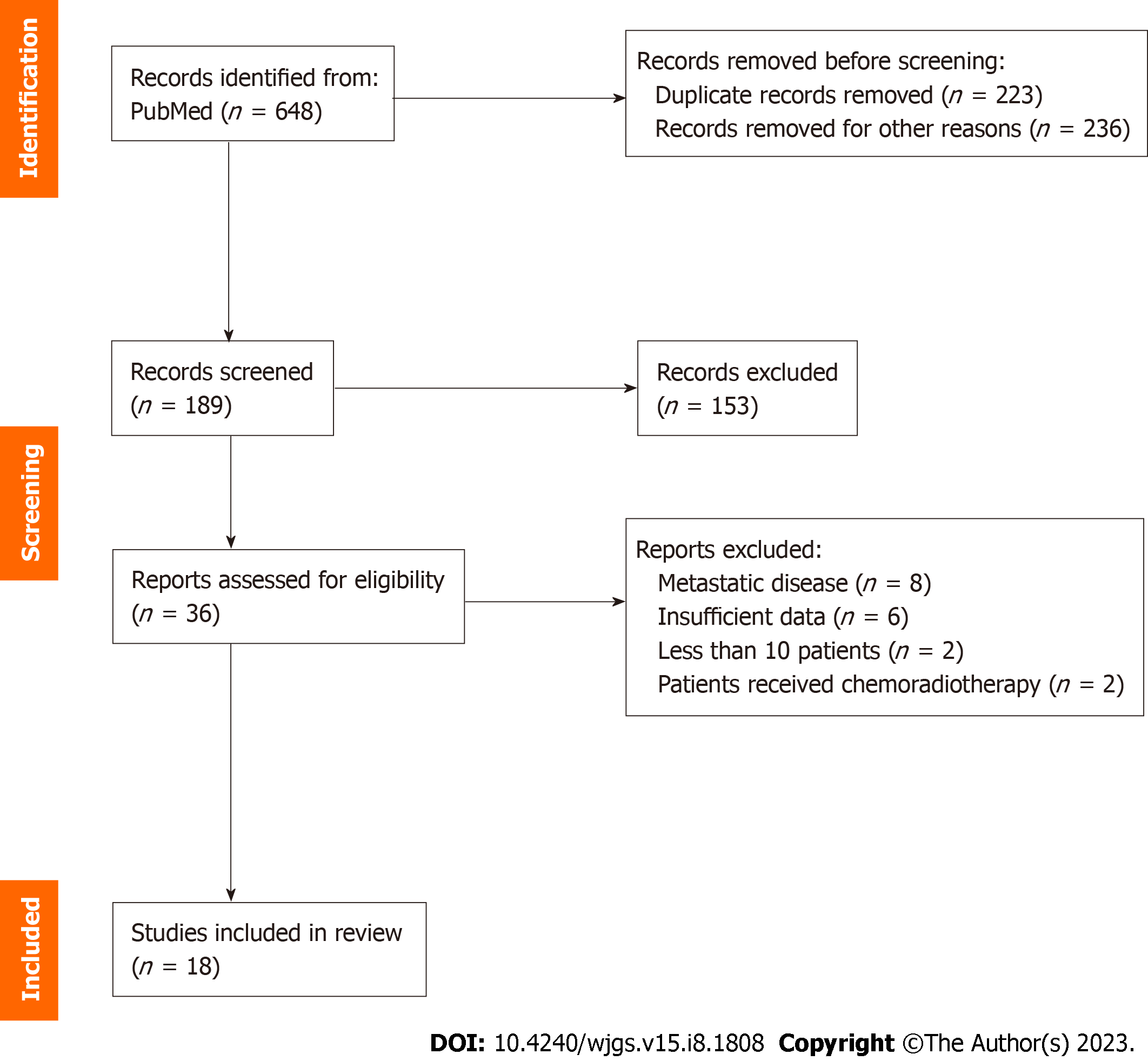

A thorough literature search was performed in PubMed using the terms “gastric cancer”, “locally advanced gastric cancer”, “adjuvant chemotherapy”, “neoadjuvant chemotherapy”, “perioperative chemotherapy”, “upfront surgery” and “surgical resection” in various combinations. The search yielded 648 results and after excluding duplicates and irrelevant studies by title and abstract, 36 were assessed for full text screening and 18 were finally included in the review. The study selection algorithm is shown in the PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1[7]. Our study protocol has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, ID CRD42023405111) and the date of the last search was February 18th, 2023.

Two reviewers (Fiflis S and Papakonstantinou M) independently completed the search and extracted the following data into a predetermined datasheet form: Author, year of publication, sample size, population sex and age, follow-up period, TNM stage, esophagogastric junction tumor involvement, length of hospital stay, type of surgery, chemotherapy regimens, OS and DFS rates, mortality and morbidity of the patients, R0 resection rates and tumor recurrence.

We included studies in the English language published over the last decade up until February 2023. The inclusion criteria were studies with patients with LAGC who had received no prior treatment and would undergo surgical resection and/or NAT. The outcomes of the studies should include data on the survival of patients after NAT and surgery and compare them to upfront surgery (US). Cohorts of patients with metastases before surgery and studies with less than 10 participants were excluded. Pilot studies, studies investigating predictive factors, case reports and letters to the editor or comments were also excluded (Table 1).

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Studies published over the last 10 yr | Studies with less than 10 patients |

| Studies in English language | Pilot studies and case reports |

| Adult patients | Patients with metastatic disease |

| Patients with locally advanced gastric cancer |

The risk of bias of each individual cohort study included in our systematic review was assessed with the Cochrane Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Cohort Studies. This tool consists of the following 8 questions: (1) Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population? (2) Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure? (3) Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study? (4) Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these prognostic variables? (5) Can we be confident in the assessment of the presence or absence of prognostic factors? (6) Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome? (7) Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? and (8) Were co-interventions similar between groups? Depending on the answer, which varies from definitely yes to probably yes, probably no or definitely no, each study is classified as low or high risk of bias.

The original search yielded 648 results and after excluding irrelevant and duplicate papers, 18 studies with 4839 patients in total were included in our systematic review[8-25]. The demographics and the clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2. All patients were treated for LAGC and were separated into two groups; one receiving NAT and then undergoing surgical resection (NAT group) and the other undergoing US (US group). After the initial intervention the patients received either adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy or no adjuvant treatment at all. The outcomes of interest were primarily the OS, the DFS and the morbidity and mortality rate, and secondarily the R0 resection rate. Seven of the studies included were propensity score-matched analyses[10,11,16,21-24]. Only the results of the matched groups were included in our study.

| Ref. | Study population | Sex | Age (yr) | EGJ involvement | Staging |

| Ahn et al[8], 2014 | 140 | 101 males, 39 females | NAT, 53.8; US, 58.9 | NS | T0, n = 2 |

| T1, n = 35 | |||||

| T2, n = 40 | |||||

| T3, n = 31 | |||||

| T4, n = 28 | |||||

| Unknown, n = 4 | |||||

| Biondi et al[9], 2018 | 417 | 262 males, 155 females | NAT, 58 ± 10; US, 55 ± 13 | n = 26 | 0, n = 1 |

| I, n = 101 | |||||

| II, n = 87 | |||||

| III, n = 169 | |||||

| IV, n = 59 | |||||

| Bracale et al[10], 2021 | 194 | 119 males, 75 females | NAT, 69.4; US, 70.5 | None | II, n = 48 |

| III, n = 146 | |||||

| Eom et al[11], 2018 | 129 | 90 males, 39 females | NAT, 53; US, 57 | None | IIIA, n = 61 |

| IIIB, n = 57 | |||||

| IV, n = 11 | |||||

| Feng et al[12], 2015 | 170 | 134 males, 36 females | 60 (21-82) | NS | T1, n = 5 |

| T2, n = 17 | |||||

| T3, n = 29 | |||||

| T4, n = 119 | |||||

| Wang et al[13], 2021 | 60 | 32 males, 28 females | 32-70 | NS | T3, n = 32 |

| T4a, n = 28 | |||||

| Xue et al[14], 2018 | 100 | 76 males, 24 females | 69 patients < 65 yr | NS | T2, n = 10 |

| T3, n = 31 | |||||

| T4a, n = 58 | |||||

| T4b, n = 1 | |||||

| Kang et al[15], 2021 | 484 | 384 males, 100 females | 58 (20-75) | NS | T2, n = 25 |

| T3, n = 116 | |||||

| T4a, n = 305 | |||||

| T4b, n = 38 | |||||

| Kano et al[16], 2019 | 76 | 61 males, 15 females | NAT, 69.3 ± 7.76; US, 70.4 ± 8.5 | None | IIB, n = 27 |

| IIIA-C, n = 49 | |||||

| Lin et al[17], 2022 | 462 | 349 males, 113 females | NAT, 58; AT, 61 | NS | T0, n = 10 |

| T1, n = 18 | |||||

| T2, n = 65 | |||||

| T3, n = 101 | |||||

| T4, n = 158 | |||||

| Marino et al[18], 2021 | 177 | 107 males, 70 females | 73.3 ± 10.4 | NS | T2, n = 4 |

| T3, n = 27 | |||||

| T4, n = 16 | |||||

| Molina et al[19], 2013 | 40 (39 surgery) | 29 males, 11 females | 64.3 (39.1-82.2) | NS | II, n = 21 |

| III, n = 19 | |||||

| Pardo et al[20], 2020 | 814 | 513 males, 295 females | 351 patients < 70; 399 patients > 70 | NS | T1, n = 6 |

| T2, n = 210 | |||||

| T3, n = 375 | |||||

| T4a, n = 164 | |||||

| T4b, n = 31 | |||||

| Wang et al[21], 2019 | 82 | 65 males, 17 females | NAT, 23 patients < 60, 18 patients > 60; US, 24 patients < 60, 17 patients > 60 | None | II, n = 22 |

| III, n = 60 | |||||

| Wang et al[22], 2021 | 778 | 580 males, 198 females | NAT, 56.13; US, 55.94 | None | II, n = 132 |

| III, n = 646 | |||||

| Wu et al[23], 2019 | 172 | 139 males, 33 females | NAT, 54.83; US, 54.98 | NS | II, n = 10 |

| III, n = 162 | |||||

| Xu et al[24], 2021 | 442 | 331 males, 114 females | NAT, 63; US, 61 | NS | T4, n = 442 |

| Zhao et al[25], 2017 | 102 | 82 males, 20 females | 59 (34-77) | NS | IIB, n = 23 |

| IIIA, n = 39 | |||||

| IIIB/C, n = 40 |

The OS ranged from 41.6% to 74.2% in the NAT group and from 30.9% to 74% in the US group[14,15,20,21]. The difference was statistically significant in 5 studies[11,21,22,24,17]. Details on the OS and the DFS of each of the included studies can be found in Table 3. In general, the OS was greater in the NAT group in all of the studies except for one, where the OS was 70% in the NAT and 74% in the US group (P > 0.05)[14]. Of note, Lin et al[17] in their study compared the results between Eastern and Western institutions. The difference in OS of patients with LAGC treated with NAT or US was significantly different in the Eastern cohort (60.1% vs 49.3% respectively, P = 0.02). In the Western cohort the OS of patients who received NAT was 57.3% and 39.5% for those undergoing US (P = 0.11)[17]. The greatest difference in OS was reported in the study of Xu et al[24] where after NAT the OS reached 72.29%, while after US it was as low as 36.22% (P < 0.001)[24].

| Ref. | Overall survival | P value | Disease-free survival | P value | ||

| NAT | US | NAT | US | |||

| Ahn et al[8], 2014 | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Biondi et al[9], 2018 | > 60 mo | 45 mo | 0.519 | NS | NS | |

| Bracale et al[10], 2021 | 72% | 71% | 0.41 | 71% | 75% | 0.34 |

| Eom et al[11], 2018 | 73.3% | 51.1% | 0.005 | 62.8% | 49.9% | 0.145 |

| Feng et al[12], 2015 | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Wang et al[13], 2021 | 63.3% | 50% | 0.215 | 60% | 33.3% | 0.019 |

| Xue et al[14], 2018 | 70% | 74% | > 0.05 | NS | NS | |

| Kang et al[15], 2021 | 74.2% | 73.4% | > 0.05 | 66.3% | 60.2% | 0.023 |

| Kano et al[16], 2019 | NS | NS | 80% | 58.7% | 0.037 | |

| Lin et al[17], 20221 | Eastern: 60.1%. Western: 57.3% | Eastern: 49.3%. Western: 39.5% | Eastern: 0.02. Western: 0.11 | NS | NS | |

| Marino et al[18], 2021 | 50 mo | 35 mo | > 0.05 | 48 mo | > 0.05 | |

| Molina et al[19], 2013 | 39.01% | 34.05% | ||||

| Pardo et al[20], 2020 | 41.6% | 38.6% | 0.089 | NS | NS | |

| Wang et al[21], 2019 | 58.7% | 30.9% | 0.008 | NS | NS | |

| Wang et al[22], 2021 | 52 mo | 26.4 mo | < 0.001 | NS2 | NS2 | |

| Wu et al[23], 2019 | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Xu et al[24], 2021 | 72.29% | 36.22% | < 0.001 | 58.53% | 30.87% | < 0.001 |

| Zhao et al[25], 2017 | 17.9 mo | 17.4 mo | > 0.05 | 16.1 mo | 15.8 mo | > 0.05 |

The highest DFS was reported in the NAT group of the Kano et al[16] cohort and was statistically significantly higher than that of the US group (80% vs 58.7%, P = 0.037). In all of the studies included, except for one, the DFS was longer after NAT, however the difference was statistically significant in 4 studies[16,24,15,13]. Bracale et al[10] reported greater DFS in the US group, but the difference was not significant (75% vs 71% after NAT, P = 0.34).

The complications related to the chemotherapy or the surgery ranged from 6.4% to 38.1% in the NAT group and from 5% to 40.5% in the US group[10,16,19,22]. The difference in morbidity between the two groups was statistically significant in two studies. In the study of Bracale et al[10] the morbidity was 38.1% in the NAT group and 21.6% in the US group (P = 0.019). In the study of Xu et al[24] the morbidity after NAT was 6.79%, while after US it was 12.67% (P = 0.037). The morbidity varied among the studies and depended on multiple factors included but not limited to chemotherapy regimen, patient status, surgical team experience, surgical technique and the extend of the disease and as a result a general conclusion could not be drawn. More detailed information is shown in Table 4. Among all the studies, death was more common in the US groups. In 7 studies no deaths occurred in the patients who received NAT, in 3 of which the mortality of the counterpart US group was 2.1%, 2.1% and 3.7% (Table 4)[8-10]. Finally, the highest mortality rate was observed in a US group, however it was not significantly different than that of the NAT group (5.3% vs 2.8%, P = 0.142)[20].

| Ref. | Morbidity | P value | Mortality | P value | ||

| NAT | US | NAT | US | |||

| Ahn et al[8], 2014 | 22.9% | 29.3% | 0 | 2.1% | ||

| Biondi et al[9], 2018 | 21.4% | 12.9% | 0.178 | 0 | 3.7% | |

| Bracale et al[10], 2021 | 38.1% | 21.6% | 0.019 | 0 | 2.1% | |

| Eom et al[11], 2018 | 14.3% | 15.1% | 0.999 | 0 | 0 | |

| Feng et al[12], 2015 | 18.8% | 22.2% | 0.704 | NS | NS | |

| Wang et al[13], 2021 | 23.1% | 30% | 0.56 | NS | NS | |

| Xue et al[14], 2018 | 30% | 28% | 0.986 | 2% | 2% | |

| Kang et al[15], 2021 | 8.1% | 5.5% | 0.175 | 0.4% | ||

| Kano et al[16], 2019 | 23.1% | 40.5% | 0.101 | NS | NS | |

| Lin et al[17], 2022 | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Marino et al[18], 2021 | Less than US | > 0.05 | NS | NS | ||

| Molina et al[19], 2013 | - | 5% | - | 2.5% | ||

| Pardo et al[20], 2020 | 11.5% | 9.9% | 0.268 | 2.8% | 5.3% | 0.142 |

| Wang et al[21], 2019 | 9% | 17% | 0.519 | 0 | 0 | |

| Wang et al[22], 2021 | 6.4% | 0 | 0.2% | 0 | ||

| Wu et al[23], 2019 | 10.5% | 15.1% | 0.361 | 0 | 0 | |

| Xu et al[24], 2021 | 6.79% | 12.67% | 0.037 | n = 172 in total | ||

| Zhao et al[25], 2017 | 14% | 15.4% | 0.844 | 0 | 0 | |

Our secondary endpoint was the comparison of the R0 resection rate between patients who received NAT and those who underwent US (Table 5). The R0 resection rates were not statistically significantly different among all the studies except for one. In the study of Wang et al[13], 84.6% of the patients underwent a complete tumor resection after NAT, while the corresponding percentage for the US group was significantly lower (56.7%, P = 0.029). In a subgroup analysis where they compared neoadjuvant cheomoradiotherapy with NAT they showed that neoadjuvant cheomoradiotherapy resulted to better R0 resection rate, although not statistically significantly different (96% vs 89%, P = 0.06)[22].

| Ref. | R0 resection rate | P value | |

| NAT | US | ||

| Ahn et al[8], 2014 | 92.2% | ||

| Biondi et al[9], 2018 | 82.9% | 83.6% | 0.449 |

| Bracale et al[10], 2021 | NS | NS | |

| Eom et al[11], 2018 | 97.7% | 97.7% | |

| Feng et al[12], 2015 | 95% | 94.4% | |

| Wang et al[13], 2021 | 84.6% | 56.7% | 0.029 |

| Xue et al[14], 2018 | 100% | 96% | |

| Kang et al[15], 2021 | NS | NS | |

| Kano et al[16], 2019 | 100% | 100% | |

| Lin et al[17], 2022 | 90.1% | ||

| Marino et al[18], 2021 | NS | NS | |

| Molina et al[19], 2013 | - | 80% | |

| Pardo et al[20], 2020 | NS | NS | |

| Wang et al[21], 2019 | 89.2% | 84.6% | > 0.05 |

| Wang et al[22], 2021 | 96%1 | 89%1 | 0.061 |

| Wu et al[23], 2019 | NS | NS | |

| Xu et al[24], 2021 | 94.12% | 89.14% | 0.072 |

| Zhao et al[25], 2017 | NS | NS | |

In our systematic review we aimed to investigate the effect of NAT in the survival of patients with LAGC in comparison to US. Most of the studies included in our systematic review showed an OS and DFS benefit in patients treated with NAT. In general, NAT does not increase morbidity and mortality after surgery therefore constitutes a safe treatment regimen for patients with LAGC. Whatsmore, Feng et al[12], Kang et al[15] and Molina et al[19] demonstrated that patients treated with NAT accomplished significant tumor downstaging which translates to better surgical outcomes. Kang et al[15] also demonstrated that patients with more advanced disease benefited the most from NAT.

However, surgery should not be delayed unnecessarily, as not all patients with LAGC will benefit from perioperative chemotherapy. GC is highly heterogeneous pathologicaly and the response to treatment could vary since different subtypes present with different tumor and clinical characteristics. Zurlo et al[1] showed in their retrospective analysis that patients with diffuse type GC had worse OS than those with intestinal type GC when NAT was implemented in their therapeutic approach. Even though histology-driven decisions are appealing, these results need to be confirmed by larger and prospective trials.

There has been a number of trials in Europe such as the MAGIC trial and the FNCLCC/FFCD trial that showed that patients submitted to NAT had longer OS and DFS compared to US patients[4,26]. Moreover, the FNCLCC/FFCD trial showed that the NAT group had higher R0 rates. It is noteworthy that the complication rates remain the same between NAT and US groups which indicates that NAT could be safely administered in clinical practice. NAT followed by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy is considered the standard of treatment in Europe and the United States.

In the Asian countries the standard of treatment differs from the West. According to the Japanese GC treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition) NAT should not be offered in LAGC patients. Instead they should undergo US followed by adjuvant chemotherapy[27]. In agreement to these guidelines, the CLASSIC trial with patients from Korea, China and Taiwan demonstrated the necessity of adjuvant chemotherapy due to the significantly higher DFS in adjuvant chemotherapy and surgery group in comparison to surgery only group (P < 0.0001)[6]. On the other hand, the RESOLVE trial in China and the PRODIGY in Korea proved that NAT significantly improves DFS and can be safely administered to patients with LAGC.

In the modern era, the research aims at the molecular level and various biomarkers, prognostic factors and immunotherapeutic agents have been introduced in the management and treatment of LAGC. For instance, the MAGIC and the CLASSIC Trials showed that there is no benefit from chemotherapy in patients with GC and microsatellite instability or mismatch repair protein deficiency[4,6]. A study performed in a Western population suggests additional molecular marker testing as patients showed better prognosis when treated with the anti-programmed cell death protein 1 agent, nivolumab[28]. These results are furtherly supported by a phase 3 trial which showed that the addition of nivolumab in the therapeutic regimen of GC patients provided a statistically significant DFS benefit[29]. Lastly, a phase 2 trial, the FIGHT study, demonstrated that Bemarituzumab, an antibody that selectively binds to fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 isoform IIb (FGFR2b) and mediates cytotoxicity, improved the OS, DFS and overall response rate when administered to patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative and FGFR2b positive unresectable locally advanced gastric tumor[30].

One limitation of our study is that not all of the patients had the same histological type of GC, which as discussed above may affect the efficacy of the chemotherapy regimen. Also, the chemotherapy regimens were not standardized among the studies. Due to that heterogeneity of data a meta-analysis could not be performed. Furthermore, most of the included studies were retrospective cohort studies, a type of study more frequently susceptible to selection or recall bias. Finally, the operations were not performed by the same surgical teams, and even though we included studies from large centers with high volume of patients the surgical technique and experience may vary.

NAT followed by surgery is safe for patients with LAGC and offers potentially better OS and DFS compared to US. However, the optimal treatment regimen for patients with LAGC today is still perplexed, as it is not distinct which patients could benefit the most from NAT. Even though D2 gastrectomy remains the gold standard in patients that can be submitted to surgery, more research is needed to clarify which LAGC patients will benefit more from NAT and immune-targeted therapies or other biological agents. Patients should also be stratified into chemosensitive and chemoresistant groups according to the tumor’s response to initial treatment for more optimal results. To conclude, since each patient with LAGC presents with different clinicopathological features and responds differently to chemotherapy, the treatment plan should be individualized in order to achieve the optimal results.

Gastric cancer (GC) is a major health concern worldwide. Currently, surgery is the mainstay treatment along with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAT) or both. However, in locally advanced GC (LAGC) upfront surgery (US) may not be the optimal approach. NAT may induce tumor downsizing and therefore offer better chances for complete resection of the tumor.

NAT could lead to complete surgical resection of the otherwise unresectable LAGC. Unfortunately, in the current literature, there are conflicting results regarding the role of NAT in the survival of patients with LAGC. We aim to investigate that role and hopefully, future research could focus on optimizing the treatment strategy of LAGC.

In our systematic review we aim to investigate the effects of NAT on the overall survival (OS), the disease-free survival (DFS), the morbidity and the mortality of patients with LAGC in comparison to US. The results of our review may add to the effort of optimizing the treatment strategy for cancer patients regarding longer survival with better quality of life.

We conducted a thorough literature search for cohort studies comparing patients with LAGC treated with US to patients treated with NAT followed by surgery. The patients’ characteristics were not statistically significantly different before the interventions and only the matched group results were included in our study.

The OS of patients with LAGC was slightly better in the groups treated with NAT than those undergoing US. Similar results were also found for DFS. Whatsmore mortality rates were higher in the US groups. These results are promising regarding the utilization of NAT in the treatment of LAGC. In the future, research on LAGC should include more patients treated in large centers with similar surgical techniques and focus on investigating the optimal NAT regimens that lead to longer survival with minimal complications.

NAT may lead to complete surgical resection of LAGC and therefore offers the potential for treatment for patients with otherwise unresectable tumors.

To clarify which patients will benefit more from which NAT regimen and also investigate the potential role of immune-targeted therapies or other biological agents in treating patients with LAGC.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sun Y, China; Zha Y, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Zurlo IV, Basso M, Strippoli A, Calegari MA, Orlandi A, Cassano A, Di Salvatore M, Garufi G, Bria E, Tortora G, Barone C, Pozzo C. Treatment of Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer (LAGC): Back to Lauren's Classification in Pan-Cancer Analysis Era? Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stewart C, Chao J, Chen YJ, Lin J, Sullivan MJ, Melstrom L, Hyung WJ, Fong Y, Paz IB, Woo Y. Multimodality management of locally advanced gastric cancer-the timing and extent of surgery. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Martenson JA. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2465] [Cited by in RCA: 2435] [Article Influence: 101.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ, Smith DB, Langley RE, Verma M, Weeden S, Chua YJ, MAGIC Trial Participants. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4899] [Cited by in RCA: 4600] [Article Influence: 242.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, Furukawa H, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y, Imamura H, Higashino M, Yamamura Y, Kurita A, Arai K; ACTS-GC Group. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 1941] [Article Influence: 107.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Chung HC, Park YK, Lee KH, Lee KW, Kim YH, Noh SI, Cho JY, Mok YJ, Ji J, Yeh TS, Button P, Sirzén F, Noh SH; CLASSIC trial investigators. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1290] [Article Influence: 99.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 40131] [Article Influence: 10032.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Ahn HS, Jeong SH, Son YG, Lee HJ, Im SA, Bang YJ, Kim HH, Yang HK. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1560-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Biondi A, Agnes A, Del Coco F, Pozzo C, Strippoli A, D'Ugo D, Persiani R. Preoperative therapy and long-term survival in gastric cancer: One size does not fit all. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:575-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bracale U, Corcione F, Pignata G, Andreuccetti J, Dolce P, Boni L, Cassinotti E, Olmi S, Uccelli M, Gualtierotti M, Ferrari G, De Martini P, Bjelović M, Gunjić D, Cuccurullo D, Sciuto A, Pirozzi F, Peltrini R. Impact of neoadjuvant therapy followed by laparoscopic radical gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection in Western population: A multi-institutional propensity score-matched study. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124:1338-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Eom BW, Kim S, Kim JY, Yoon HM, Kim MJ, Nam BH, Kim YW, Park YI, Park SR, Ryu KW. Survival Benefit of Perioperative Chemotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: a Propensity Score Matched Analysis. J Gastric Cancer. 2018;18:69-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Feng D, Leong M, Li T, Chen L. Surgical outcomes in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer treated with S-1 and oxaliplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang F, Qu A, Sun Y, Zhang J, Wei B, Cui Y, Liu X, Tian W, Li Y. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus postoperative adjuvant XELOX chemotherapy versus postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with XELOX regimen for local advanced gastric cancer-A randomized, controlled study. Br J Radiol. 2021;94:20201088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xue K, Ying X, Bu Z, Wu A, Li Z, Tang L, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Ji J. Oxaliplatin plus S-1 or capecitabine as neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer with D2 lymphadenectomy: 5-year follow-up results of a phase II-III randomized trial. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30:516-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kang YK, Yook JH, Park YK, Lee JS, Kim YW, Kim JY, Ryu MH, Rha SY, Chung IJ, Kim IH, Oh SC, Park YS, Son T, Jung MR, Heo MH, Kim HK, Park C, Yoo CH, Choi JH, Zang DY, Jang YJ, Sul JY, Kim JG, Kim BS, Beom SH, Cho SH, Ryu SW, Kook MC, Ryoo BY, Yoo MW, Lee NS, Lee SH, Kim G, Lee Y, Lee JH, Noh SH. PRODIGY: A Phase III Study of Neoadjuvant Docetaxel, Oxaliplatin, and S-1 Plus Surgery and Adjuvant S-1 Versus Surgery and Adjuvant S-1 for Resectable Advanced Gastric Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2903-2913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kano M, Hayano K, Hayashi H, Hanari N, Gunji H, Toyozumi T, Murakami K, Uesato M, Ota S, Matsubara H. Survival Benefit of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with S-1 Plus Docetaxel for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:1805-1813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lin JX, Tang YH, Lin GJ, Ma YB, Desiderio J, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Zheng CH, Parisi A, Truty MJ, Huang CM. Association of Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Overall Survival Among Patients With Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e225557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marino E, Graziosi L, Donini A. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: Where we Stand; An Italian Single Center Perspective. In Vivo. 2021;35:3459-3466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Molina R, Lamarca A, Martínez-Amores B, Gutiérrez A, Blázquez A, López A, Granell J, Álvarez-Mon M. Perioperative chemotherapy for resectable gastroesophageal cancer: a single-center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:814-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pardo F, Osorio J, Miranda C, Castro S, Miró M, Luna A, Garsot E, Momblán D, Galofré G, Rodríguez-Santiago J, Pera M; Spanish EURECCA Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Group. A real-life analysis on the indications and prognostic relevance of perioperative chemotherapy in locally advanced resectable gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22:1335-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang K, Ren Y, Ma Z, Li F, Cheng X, Xiao J, Zhang S, Yu Z, Yang H, Zhou H, Li Y, Liu H, Jiao ZY. Docetaxel, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil (FLOT) as preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy compared with surgery followed by chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced gastric cancer: a propensity score-based analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:3009-3020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang T, Chen Y, Zhao L, Zhou H, Wu C, Zhang X, Zhou A, Jin J, Zhao D. The Effect of Neoadjuvant Therapies for Patients with Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Study. J Cancer. 2021;12:379-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu L, Ge L, Qin Y, Huang M, Chen J, Yang Y, Zhong J. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus upfront surgery for locally advanced gastric cancer: a propensity score matching analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:6011-6018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xu W, Wang L, Yan C, He C, Lu S, Ni Z, Hua Z, Zhu Z, Sah BK, Yang Z, Zheng Y, Feng R, Li C, Yao X, Chen M, Liu W, Yan M. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Versus Direct Surgery for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer With Serosal Invasion (cT4NxM0): A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:718556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhao Q, Li Y, Huang J, Fan L, Tan B, Tian Y, Yang P, Jiao Z, Zhao X, Zhang Z, Wang D, Liu Y. Short-term curative effect of S-1 plus oxaliplatin as perioperative chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer: a prospective comparison study. Pharmazie. 2017;72:236-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, Conroy T, Bouché O, Lebreton G, Ducourtieux M, Bedenne L, Fabre JM, Saint-Aubert B, Genève J, Lasser P, Rougier P. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1715-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1216] [Cited by in RCA: 1501] [Article Influence: 107.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 1332] [Article Influence: 333.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Salati M, Ghidini M, Paccagnella M, Reggiani Bonetti L, Bocconi A, Spallanzani A, Gelsomino F, Barbin F, Garrone O, Daniele B, Dominici M, Facciorusso A, Petrillo A. Clinical Significance of Molecular Subtypes in Western Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Real-World Multicenter Experience. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, Zander T, Van Cutsem E, Piessen G, Mendez G, Feliciano J, Motoyama S, Lièvre A, Uronis H, Elimova E, Grootscholten C, Geboes K, Zafar S, Snow S, Ko AH, Feeney K, Schenker M, Kocon P, Zhang J, Zhu L, Lei M, Singh P, Kondo K, Cleary JM, Moehler M; CheckMate 577 Investigators. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1191-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 1077] [Article Influence: 269.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wainberg ZA, Enzinger PC, Kang YK, Qin S, Yamaguchi K, Kim IH, Saeed A, Oh SC, Li J, Turk HM, Teixeira A, Borg C, Hitre E, Udrea AA, Cardellino GG, Sanchez RG, Collins H, Mitra S, Yang Y, Catenacci DVT, Lee KW. Bemarituzumab in patients with FGFR2b-selected gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FIGHT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1430-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |