Published online Jun 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i6.1116

Peer-review started: December 27, 2022

First decision: January 20, 2023

Revised: January 21, 2023

Accepted: April 13, 2023

Article in press: April 13, 2023

Published online: June 27, 2023

Processing time: 170 Days and 4.8 Hours

Majority of adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO) cases can be managed non-operatively. However, a proportion of patients failed non-operative management.

To evaluate the predictors of successful non-operative management in adhesive SBO.

A retrospective study was performed for all consecutive cases of adhesive SBO from November 2015 to May 2018. Data collated included basic demographics, clinical presentation, biochemistry and imaging results and management out

Of 252 patients were included in the final analysis; group A (n = 90) (35.7%) and group B (n = 162) (64.3%). There were no differences in the clinical features between both groups. Laboratory tests of inflammatory markers and lactate levels were similar in both groups. From the imaging findings, the presence of a definitive transition point [odds ratio (OR) = 2.67, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.98-7.32, P = 0.048], presence of free fluid (OR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.15-3.89, P = 0.015) and absence of small bowel faecal signs (OR = 1.70, 95%CI: 1.01-2.88, P = 0.047) were predictive of the need of surgical intervention. In patients that received water soluble contrast medium, the evidence of contrast in colon was 3.83 times predictive of successful non-operative management (95%CI: 1.79-8.21, P = 0.001).

The computed tomography findings can assist clinicians in deciding early surgical intervention in adhesive SBO cases that are unlikely to be successful with non-operative management to prevent associated morbidity and mortality.

Core Tip: Adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO) is a common acute surgical presentation. Majority of the cases can be managed successfully with non-operative management. The findings on computed tomography abdomen/pelvis are useful in predicting patients that are unlikely to resolve with conservative management for adhesive SBO and therefore guide decision-making in early surgical intervention to prevent morbidities associated with it.

- Citation: Ng ZQ, Hsu V, Tee WWH, Tan JH, Wijesuriya R. Predictors for success of non-operative management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(6): 1116-1124

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i6/1116.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i6.1116

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) is one of the most common presentations in acute care surgery, accounting to 15% of cases[1]. Majority of cases are secondary to either adhesions from previous surgeries or incarcerated hernia. There has been a paradigm shift from exploratory laparotomy to non-operative management in patients presenting with adhesive SBO with reasonable success over the past decade[2]. Nevertheless, a small proportion of patient may fail non-operative management. The challenge then lies in early identification of this subset of patients that are unlikely to resolve to prevent development of ischaemic small bowel that carries a significant morbidity[3,4].

A few studies have attempted to investigate the various predictive factors for failures of non-operative management in adhesive SBO including clinical, laboratory tests and imaging findings with mixed sensitivities and specificities[5]. It can be attributed to the subjective clinical findings including components of the history and examination findings and maybe affected by the level of experience of the clinician. The aim of this study was to evaluate the predictors for successful non-operative management of adhesive SBO.

Ethical approval was obtained from the St John of God Healthcare’s ethics committee (Ref: 1358). A retrospective review of all consecutive cases of SBO admitted to St John of God Midland Hospital from November 2015 to May 2018 was performed. The St John of God Midland Hospital is a secondary hospital in Western Australia, staffed with an onsite General Surgery registrar with a dedicated on-call consultant surgeon with 24-h access to anaesthetic care and emergency theatre. Radiological services such as X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scans are available 24 h. The CT scans are reported by a consultant radiologist.

Data collected included basic demographics, co-morbidities, previous history of abdominal surgery, history of presentation (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, obstipation, flatus), vitals on presentation (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and temperature), biochemistry tests [white cell count, c-reactive protein (CRP), urea, creatinine and lactate], imaging findings [abdominal X-ray (AXR) and CT] management outcomes (non-operative vs surgical intervention) and length of stay.

The inclusion criteria were patients ≥ 16 years of age and SBO secondary to adhesions. Exclusion criteria included: Patients younger than 16 years old, SBO in virgin abdomen, immediate post-operation, secondary to other causes such as stricture, incarceration, inflammatory bowel disease, volvulus, foreign body, bezoar, small bowel malignancy, peritoneal malignancy, secondary to large bowel obstruction, ileus and patients without a CT scan for analysis.

The patients were divided into two groups for comparison and analysis; group A: Operative (including patients that underwent immediate surgery and patients failed initial non-operative management and underwent surgical intervention) and group B: Non-operative. Non-operative management included nil by mouth, nasogastric tube insertion for decompression of stomach, intravenous fluid resuscitation and/or administration of water-soluble contrast. The nasogastric tube was left to decompress the stomach for four hours prior to administration of water-soluble contrast (Gastrografin - mixture of nonabsorbable sodium diatrizoate and meglumine diatrizoate 100 mL undiluted). The nasogastric tube was clamped for two hours and an AXR was performed at six hours post-administration. If the contrast was not seen in the large bowel at 6-h and patient remains clinically well, a repeat AXR was performed the following day. If there was presence of contrast in the large bowel on AXR, the patients were allowed to have clear liquids and diet was upgraded in a stepwise approach. If there was no contrast in the large bowel (including the repeat AXR), surgical intervention was performed. For patients that underwent immediate surgical intervention on presentation, it was at the discretion of the on-call consultant surgeon.

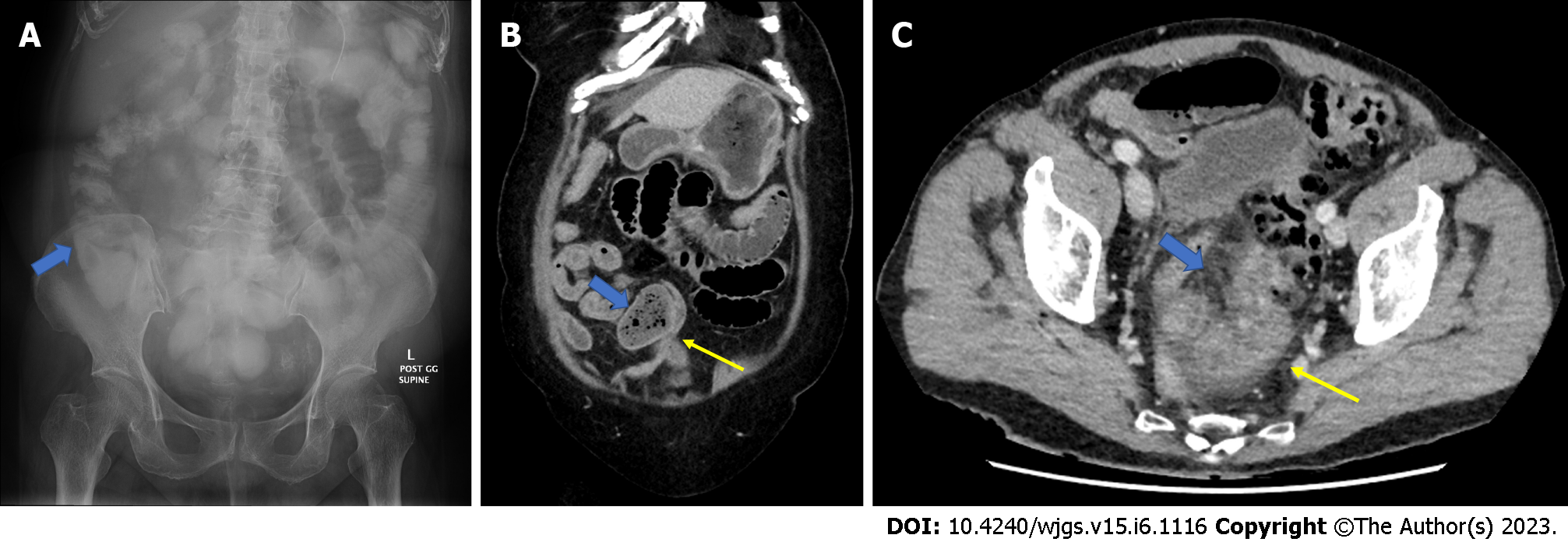

The standard CT scans were performed with 64-slice and protocoled with intravenous iodinated contrast and taken at the portal venous phase. The only exceptions were allergy to iodine contrast or evidence of acute or chronic renal failure. The CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis performed on presentation were reviewed by an experienced radiologist (William Tee) who was blinded to the clinical history and management outcomes. The CTs were reviewed for: Presence of SBO, the cause of the SBO, small bowel faecal sign, presence of definitive transition point, grade of obstruction, presence of free fluid, distribution of free fluid, presence of mesenteric fat stranding and presence of small bowel thickening/abnormal enhancement. The AXRs were also reviewed for the presence to contrast in the colon (Figure 1A).

The definitions used for the CT findings were as follows: (1) Presence of SBO: Dilatation of small bowel; (2) Adhesive SBO: No other causes of SBO such as incarceration in a hernia, volvulus, foreign body, stricture, inflammatory bowel disease, primary small bowel malignancy, secondary to large bowel obstruction or ileus are found; (3) Definitive transition point (Figure 1B): There is a traceable dilated small bowel loop to another area of collapsed small bowel loop; (4) Grade of obstruction: The largest diameter of the small bowel loop is measured; (5) Presence of mesenteric stranding (Figure 1C): Distinct hazy/wavy stranding at the mesentery; (6) Small bowel thickening/abnormal enhancement (Figure 1C): Near concentric circumferential thickening and/or distinct lower attenuation of the thickened wall; (7) Presence of free fluid: Categorized into nil, trace, small and large; (8) Trace: Barely there only a sliver of fluid; Usually only perceptible by a radiologist; (9) Small: Visually there and easy to be perceived by a non-radiologist clinician; (10) Large: Unequivocal large volume; a striking feature of the scan easily spotted by a non-radiologist clinician; and (11) Distribution of free fluid: Categorized into pelvis, paracolic gutters, peri-small bowel/mesentery/central.

SPSS version 16 was used for analysis of the data. Demographics, clinical presentation, imaging variable were compared between two groups using chi square and t test depending on if the variable is categorical or numerical. P value less than 0.05 is regarded as statistical significance. The categorical data were presented as frequency and percentage and numerical data were presented with mean and standard deviation. Odds ratio was calculated for categorical variable.

Of 426 patients presented with SBO during the study period. 252 adhesive SBO patients were included in the final analysis (Table 1). Of 252 patients, 90 (male:female = 33:57) were in group A (including 20 patients that underwent immediate surgery) and 162 (male:female = 62:100) were in group B. There was no difference in the mean age in both groups (68.89 years vs 68.13 years, P = 0.72). There was no difference in patients with comorbidities in both groups (36.2% vs 63.8%, P = 0.57). Both group of patients had similar average number of previous abdominal surgery (1.92 vs 2.12, P = 0.28).

| Group A (n = 90) | Group B (n = 162) | P value | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 57 (36.3) | 100 (63.7) | |

| Male | 33 (34.7) | 62 (65.3) | 0.80 |

| Comorbidities | 85 (36.2) | 150 (63.8) | |

| No comorbidities | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | 0.57 |

| No of previous abdominal surgery (mean ± SD) | 1.92 ± 1.18 | 2.12 ± 1.44 | 0.28 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 68.89 ± 17.37 | 68.13 ± 15.56 | 0.72 |

There were no differences in the presence of nausea (group A vs B: 35.7% vs 64.3%, P = 0.76) and vomiting (34.2% vs 65.8%, P = 0.42) in both groups. The symptoms of abdominal pain (35.3% vs 64.7%, P = 0.63) and abdominal distention (37.0% vs 63.0%, P = 0.22) were also similar in both groups. The presence of flatus (38.5% vs 61.5%, P = 0.56) or the absence of obstipation (31.9% vs 68.1%, P = 0.24) did not differ in both groups (Table 2).

| Group A (n = 90) | Group B (n = 162) | P value | |

| Nausea | 56 (35.7) | 101 (64.3) | |

| No nausea | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) | 0.76 |

| Vomiting | 63 (34.2) | 121 (65.8) | |

| No vomiting | 27 (39.7) | 41 (60.3) | 0.42 |

| Abdominal pain | 83 (35.3) | 152 (64.7) | |

| No pain | 7 (41.2) | 10 (58.8) | 0.63 |

| Abdominal distension | 37 (37.0) | 63 (63.0) | |

| No distension | 50 (33.8) | 98 (66.2) | 0.22 |

| Flatus | 37 (38.5) | 59 (61.5) | |

| No flatus | 53 (34.0) | 103 (66.0) | 0.56 |

| No obstipation | 37 (31.9) | 79 (68.1) | |

| Obstipation | 53 (39.0) | 83 (61.0) | 0.24 |

The physiological parameters on arrival were similar in both groups (Table 3): Heart rate (81.20 beats/min vs 82.89 beats/min, P = 0.474), systolic blood pressure (142.51 mm/Hg vs 146.79 mm/Hg, P = 0.285), diastolic blood pressure (69.65 mm/Hg vs 69.67 mm/Hg, P = 0.994) and respiratory rate (20.15/min vs 19.50/min, P = 0.559).

| Group A (mean ± SD) | Group B (mean ± SD) | P value | |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 81.20 ± 15.67 | 82.89 ± 16.74 | 0.474 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 142.51 ± 26.97 | 146.79 ± 28.09 | 0.285 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 69.65 ± 22.08 | 69.67 ± 20.17 | 0.994 |

| Respiratory rate (/min) | 20.15 ± 10.29 | 19.50 ± 3.68 | 0.559 |

| Temperature (ºC) | 36.56 ± 0.77 | 36.52 ± 0.72 | 0.697 |

| White cell count (× 109/L) | 12.27 ± 3.86 | 11.89 ± 3.96 | 0.495 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 24.96 ± 60.88 | 21.81 ± 45.25 | 0.691 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 8.77 ± 6.81 | 9.40 ± 6.59 | 0.606 |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 103.75 ± 55.35 | 110.00 ± 131.23 | 0.660 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.110 ± 0.97 | 1.942 ± 1.23 | 0.522 |

Both the inflammatory markers did not differ in both groups on presentation: White cell count (group A vs B: 12.27 × 109/L vs 11.89 × 109/L, P = 0.495) and CRP (24.96 mg/L vs 21.81 mg/L, P = 0.691). Urea (8.77 mmol/L vs 9.40 mmol/L, P = 0.606) and creatinine (103.75 μmol/L vs 110.00 μmol/L, P = 0.660) levels were also similar in both groups. The lactate level was not significantly different (2.110 mmol/L vs 1.942 mmol/L, P = 0.522).

From the review of CT scan (Table 4), the findings of a definitive transition point [odds ratio (OR) = 2.67, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.98-7.32, P = 0.048], presence of free fluid (OR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.15-3.89, P = 0.015) and absence of small bowel faecal signs (OR = 1.70, 95%CI: 1.01-2.88, P = 0.047) were predictive of the need of surgical intervention. The presence of mesenteric stranding (OR = 1.69, 95%CI: 0.97-2.94, P = 0.061) showed a trend towards prediction of the need of surgical intervention but was not statistically significant. The small bowel thickening/abnormal enhancement (OR = 1.76, 95%CI: 0.77-4.08, P = 0.177) and the grade of obstruction did not predict the need for surgical intervention (36.87 mm vs 37.35 mm, P = 0.601).

| Group A (n = 90) | Group B (n = 162) | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Definitive transition point | 85 (94.4) | 140 (86.4) | 2.67 (0.975-7.318) | 0.048 |

| No transition point | 5 (5.6) | 22 (13.6) | ||

| Mesenteric stranding | 64 (71.1) | 96 (59.3) | 1.69 (0.973-2.942) | 0.061 |

| No mesenteric stranding | 26 (28.9) | 66 (40.7) | ||

| Small bowel thickening | 12 (13.3) | 13 (8.0) | 1.76 (0.768-4.084) | 0.177 |

| No small bowel thickening | 78 (86.7) | 149 (92) | ||

| Water-soluble contrast medium | 42 (46.7) | 98 (60.5) | 0.55 (0.323-0.936) | 0.024 |

| Did not receive water-soluble contrast medium | 47 (53.3) | 60 (39.5) | ||

| Presence of free fluid | 72 (80) | 106 (65.4) | 2.11 (1.149-3.888) | 0.015 |

| No free fluid | 18 (20) | 56 (34.6) | ||

| No small bowel faecal sign | 42 (46.7) | 55 (34.0) | 1.70 (1.005-2.882) | 0.047 |

| Small bowel faecal sign present | 48 (53.3) | 107 (66.0) | ||

| Contrast reaches small bowel only | 23 (25.6) | 34 (21.0) | 3.83 (1.790- 8.209)1 | 0.001 |

| Contrast reach large bowel | 19 (74.4) | 76 (79.0) | ||

| Grade of obstruction (proximal small bowel diameter in mm), mean ± SD | 36.87 ± 7.53 | 37.35 ± 6.77 | 0.601 |

In patients that received water soluble contrast medium, the evidence of contrast reaching the colon was 3.83 times more successful in non-operative management of adhesive SBO (95%CI: 1.79-8.21, P = 0.001). Length of stay was significantly shorted in group A (4.43 d) that B (6.81 d) (P = 0.002).

Adhesive SBO remains a common acute surgical presentation. There has been mixed evidence from systematic review and meta-analysis regarding the outcomes of operative vs non-operative management of adhesive SBO due to the heterogeneity of comparison groups[6,7]. Early recognition with appropriate management is key to prevent delay access to theatre in patients that are unlikely to resolve with non-operative management[4]. This study confirms the value of the CT findings in predicting patients that are unlikely to resolve with non-operative management for adhesive SBO.

Some of the studies have proposed models based on clinical and radiological findings to accurately predict the need of surgical intervention in adhesive SBO[8-11]. It is yet to be adopted in routine clinical practice. It is not surprising that the clinical features did not differ between both groups in this study as often these are subjective to the interpretation of the clinicians. In two studies[9,10], absence of flatus has a sensitivity that ranged from 19%-37% and specificity from 94%-95% and positive predictive value 56%-86%. Often, during the early stages of the SBO, these symptoms may mirror other conditions. Schwenter et al[12] reported six independent risk factors (pain duration > 4 d, guarding, leucocytosis > 10, CRP > 75 and CT findings) to be useful in predicting strangulation/ischemia of small bowel. Based on the six risk factors, a score of 3 had 90.8% specificity and 67.7% sensitivity for bowel resection and a score of 4 or more was 100% predictive. In real clinical practice, the duration of symptoms is often inaccurate to guide decision making. The inflammatory markers were similar in our study as it could be secondary to other causes and time dependent. One of the CT findings reported in this study of free fluid > 500mL can be largely subjective. In our study, interestingly, the presence of a definitive transition point was a predictor of successful non-operative management of adhesive SBO. This finding is not routinely reported as a predictor in the literature. It is usually a sign used to determine and confirm the presence of SBO. In our study, it could be explained that more cases were detected to have transition point on this independent review by the radiologist than first reported. The presence of free fluid and absence of small bowel faecal sign are a predictor of the need of surgical intervention which is concordant with the studies in the literature[5,8-10].

The presence of other two CT findings of mesenteric stranding and small bowel thickening did not achieve statistical significance which could be explained by the duration of symptoms/presentation as it is often a late sign that arose as a result of small bowel ischemia and venous congestion and often subjected to interobserver variability in interpretation. In another study, distal (ileal) obstruction, maximum small bowel diameter over abdominal diameter ratio were associated with failure of non-operative management[13].

The administration of water-soluble contrast medium in adhesive SBO has both diagnostic and therapeutic benefits[14]. Its mechanism of action is postulated to be driven by the gradient that reduces the oedema via drawing of water from the bowel wall to the intraluminal space which leads to improve blood flow and enhances smooth muscle contractility. There remains no standardized protocol for the volume of water-soluble contrast medium, timing to administration, time for follow-up AXR and duration following AXR to surgery in cases that failed to progress[14,15]. The Bologna guidelines in 2017 suggested that if the water-soluble contrast medium fails to reach the colon within 24 h, they should be explored surgically[2]. A Cochrane review and a meta-analysis by Koh et al[16] showed that it did not reduce the surgery rates. Its role in the setting of adhesive SBO should be interpreted as an effective predictor for the need of operative intervention. There is a small proportion of patients that will still require surgical intervention despite having water-soluble contrast medium within the colon due to incomplete resolution following introduction of oral intake. Most often, the patients will have recurrence of the initial symptoms and a repeat AXR showing persistent dilated small bowel loops. In this setting, the clinician has the option of persisting with non-operative management or for consideration of operative intervention based on the patient’s clinical condition. There are no formal guidelines to dictate this scenario.

The combined CT findings and utility of water-soluble contrast medium from this study can assist clinician in early decision making of surgical intervention. There is some evidence which suggest that early laparoscopic surgical adhesiolysis reduces the recurrent SBO rates. This trend was observed in a 10-year population-based analysis from Canada between 2005-2014 which saw an increase in early intervention and use of laparoscopic approach[17]. This could be considered in expert hands who are competent in laparoscopic approach. O’connor and Winter[18] showed that the success rate of laparoscopy was 73.4% if it is secondary to a single-band adhesion. This could be difficult to determine as shown in the LASSO randomized trial which did not show any significant difference between laparoscopic vs open adhesiolysis in morbidity and mortality[19]. Consideration should be given for the likelihood of resolution with non-operative management as the reported recurrence rate has been up to 16%-53% and the expertise available in laparoscopy[20]. In the review by O’connor and Winter[18], there was 29% of conversion to laparotomy due to dense adhesions, bowel resection, unidentified pathology and iatrogenic injury. The enterotomy rate was 6.6% in this study; if unrecognized could have serious implications. With the CT findings and use of water-soluble contrast medium, it will allow frank discussion with frail and co-morbid patients to set the ceiling of care in the event of failure of non-operative management and/or worsening of condition as the one-year mortality following emergency laparotomy remains alarming at 30% despite improvement at early outcomes[21].

The strength of this study was the imaging findings were reviewed by an independent experienced radiologist who was not involved in the initial reporting of the CT or AXR results and was blinded from the clinical indications and outcomes. This study was limited by the retrospective nature where there was an inherent bias in patients that underwent immediate surgical intervention on presentation which was at the discretion of the attending surgeon. This may have led to certain CT findings such as mesenteric stranding and small bowel thickening to be not statistically significant despite being potentially indicative of ischemia[11]. The interpretation of the data on clinical presentation may be subjective as the duration of individual symptoms may not be known and are only recorded as either present or absent. Nevertheless, the findings of this study are not to replace clinical acumen but to assist the clinicians in early decision making in patients that fail to show signs of clinical progress.

Majority of adhesive SBO can be managed successfully with non-operative intervention with water-soluble contrast medium as a very effective early predictor. The CT scan features identified in this study are easily detectable and should encourage close monitoring, early planning for surgical intervention if failing non-operative approach to prevent development of bowel ischemia necessitating bowel resection.

Adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO) is a common presentation in acute care surgery. Majority of cases are managed with non-operative approach successfully. Nevertheless, there is a small proportion of patients will fail non-operative management and require surgical intervention.

The delay surgical intervention in patients that fail non-operative management in adhesive SBO may result in small bowel ischemia requiring resection. This may lead to further morbidity and mortality.

The aim of this study was to identify predictors from clinical presentation, laboratory tests and imaging results that may help identify cases of adhesive SBO that are unlikely to resolve with non-operative management.

A retrospective analysis of all cases of SBO in our institute were undertaken. The cases of SBO secondary to causes such as incarceration, tumour, volvulus, inflammatory bowel disease etc were excluded. The computed tomography (CT) scans were independently reviewed by a consultant radiologist who was blinded to the outcomes for specific signs that may determine the success of non-operative management of adhesive SBO.

Clinical presentation and laboratory results were not predictive of the success of non-operative management of SBO. Only the CT findings of a definitive transition point, presence of free fluid and absence of small bowel faecal sign were predictive of the need of surgical intervention in adhesive SBO.

The CT findings can assist clinicians in deciding early surgical intervention in adhesive SBO cases that are unlikely to be successful with non-operative management to prevent associated morbidity and mortality.

Future studies should focus on universal definitions of the CT findings and outcomes to allow accurate comparison of the efficacy of the therapeutic options.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Australia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ma H, China; Meshikhes AW, Saudi Arabia S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Menzies D, Ellis H. Intestinal obstruction from adhesions--how big is the problem? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:60-63. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Galati M, Smerieri N, Biffl WL, Ansaloni L, Tugnoli G, Velmahos GC, Sartelli M, Bendinelli C, Fraga GP, Kelly MD, Moore FA, Mandalà V, Mandalà S, Masetti M, Jovine E, Pinna AD, Peitzman AB, Leppaniemi A, Sugarbaker PH, Goor HV, Moore EE, Jeekel J, Catena F. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2013 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Miller G, Boman J, Shrier I, Gordon PH. Natural history of patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1240-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bauer J, Keeley B, Krieger B, Deliz J, Wallace K, Kruse D, Dallas K, Bornstein J, Chessin D, Gorfine S. Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: Early Operative versus Observational Management. Am Surg. 2015;81:614-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang PF, Rabinowitz DP, Wong SW, Khan MA, Gandy RC. Comparative Validation of Abdominal CT Models that Predict Need for Surgery in Adhesion-Related Small-Bowel Obstruction. World J Surg. 2017;41:940-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Panda N, Khan RMA, Bandyopadhyay SK, Dalmia S, Malik S, Huq Z, Mansour M. Operative versus non-operative management of adhesive small bowel obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2017;45:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thornblade LW, Verdial FC, Bartek MA, Flum DR, Davidson GH. The Safety of Expectant Management for Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: A Systematic Review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:846-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zielinski MD, Eiken PW, Bannon MP, Heller SF, Lohse CM, Huebner M, Sarr MG. Small bowel obstruction-who needs an operation? A multivariate prediction model. World J Surg. 2010;34:910-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zielinski MD, Eiken PW, Heller SF, Lohse CM, Huebner M, Sarr MG, Bannon MP. Prospective, observational validation of a multivariate small-bowel obstruction model to predict the need for operative intervention. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:1068-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kulvatunyou N, Pandit V, Moutamn S, Inaba K, Chouliaras K, DeMoya M, Naraghi L, Kalb B, Arif H, Sravanthi R, Joseph B, Gries L, Tang AL, Rhee P. A multi-institution prospective observational study of small bowel obstruction: Clinical and computerized tomography predictors of which patients may require early surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:393-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chai Y, Xing J, Lv P, Liang P, Xu H, Yue S, Gao J. Evaluation of ischemia and necrosis in adhesive small bowel obstruction based on CT signs: Subjective visual evaluation and objective measurement. Eur J Radiol. 2022;147:110115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schwenter F, Poletti PA, Platon A, Perneger T, Morel P, Gervaz P. Clinicoradiological score for predicting the risk of strangulated small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1119-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maraux L, Dammaro C, Gaillard M, Lainas P, Derienne J, Maitre S, Chague P, Rocher L, Dagher I, Tranchart H. Predicting the Need for Surgery in Uncomplicated Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: A Scoring Tool. J Surg Res. 2022;279:33-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ceresoli M, Coccolini F, Catena F, Montori G, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L. Water-soluble contrast agent in adhesive small bowel obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic and therapeutic value. Am J Surg. 2016;211:1114-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Köstenbauer J, Truskett PG. Current management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:1117-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Koh A, Adiamah A, Chowdhury A, Mohiuddin MK, Bharathan B. Therapeutic Role of Water-Soluble Contrast Media in Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:473-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Behman R, Nathens AB, Look Hong N, Pechlivanoglou P, Karanicolas PJ. Evolving Management Strategies in Patients with Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: a Population-Based Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:2133-2141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | O'Connor DB, Winter DC. The role of laparoscopy in the management of acute small-bowel obstruction: a review of over 2,000 cases. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sallinen V, Di Saverio S, Haukijärvi E, Juusela R, Wikström H, Koivukangas V, Catena F, Enholm B, Birindelli A, Leppäniemi A, Mentula P. Laparoscopic versus open adhesiolysis for adhesive small bowel obstruction (LASSO): an international, multicentre, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:278-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lorentzen L, Øines MN, Oma E, Jensen KK, Jorgensen LN. Recurrence After Operative Treatment of Adhesive Small-Bowel Obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ng ZQ, Weber D. One-Year Outcomes Following Emergency Laparotomy: A Systematic Review. World J Surg. 2022;46:512-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |