Published online Jun 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i6.1104

Peer-review started: September 30, 2022

First decision: January 3, 2023

Revised: January 29, 2023

Accepted: April 7, 2023

Article in press: April 7, 2023

Published online: June 27, 2023

Processing time: 258 Days and 11.3 Hours

Intersphincteric resection (ISR), the ultimate anus-preserving technique for ultralow rectal cancers, is an alternative to abdominoperineal resection (APR). The failure patterns and risk factors for local recurrence and distant metastasis remain controversial and require further investigation.

To investigate the long-term outcomes and failure patterns after laparoscopic ISR in ultralow rectal cancers.

Patients who underwent laparoscopic ISR (LsISR) at Peking University First Hospital between January 2012 and December 2020 were retrospectively reviewed. Correlation analysis was performed using the Chi-square or Pearson's correlation test. Prognostic factors for overall survival (OS), local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were analyzed using Cox regression.

We enrolled 368 patients with a median follow-up of 42 mo. Local recurrence and distant metastasis occurred in 13 (3.5%) and 42 (11.4%) cases, respectively. The 3-year OS, LRFS, and DMFS rates were 91.3%, 97.1%, and 90.1%, respectively. Multivariate analyses revealed that LRFS was associated with positive lymph node status [hazard ratio (HR) = 5.411, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.413-20.722, P = 0.014] and poor differentiation (HR = 3.739, 95%CI: 1.171-11.937, P = 0.026), whereas the independent prognostic factors for DMFS were positive lymph node status (HR = 2.445, 95%CI: 1.272-4.698, P = 0.007) and (y)pT3 stage (HR = 2.741, 95%CI: 1.225-6.137, P = 0.014).

This study confirmed the oncological safety of LsISR for ultralow rectal cancer. Poor differentiation, (y)pT3 stage, and lymph node metastasis are independent risk factors for treatment failure after LsISR, and thus patients with these factors should be carefully managed with optimal neoadjuvant therapy, and for patients with a high risk of local recurrence (N + or poor differentiation), extended radical resection (such as APR instead of ISR) may be more effective.

Core Tip: We aimed to investigate the failure patterns and risk factors for local recurrence and distant metastasis in 368 patients who underwent iaparoscopic Intersphincteric resection (LsISR). Local recurrence and distant metastasis occurred in 13 (3.5%) and 42 (11.4%) patients, respectively. The 3-year overall survival, local recurrence-free survival, and distant metastasis-free survival rates were 91.3%, 97.1%, and 90.1%, respectively. Multivariate analyses revealed that LRFS was associated with positive lymph node status and poor differentiation, whereas the independent prognostic factors for DMFS were positive lymph node status and (y)pT3 stage. We believe that our study makes a significant contribution to the literature because it confirmed the oncological safety of LsISR for ultralow rectal cancer. This paper will be of interest to the readership of your journal because it demonstrated that poor differentiation, (y)pT3 stage, and lymph node metastasis are independent risk factors for treatment failure after LsISR, and thus patients with these factors should be carefully managed with optimal neoadjuvant therapy and surgical strategy.

- Citation: Qiu WL, Wang XL, Liu JG, Hu G, Mei SW, Tang JQ. Long-term outcomes and failure patterns after laparoscopic intersphincteric resection in ultralow rectal cancers. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(6): 1104-1115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i6/1104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i6.1104

Ultralow rectal cancer refers to cancer located in the lower part of the rectum, < 5 cm from the anal verge (AV)[1]. Intersphincteric resection (ISR), a sphincter-preserving surgical technique, is a better choice for patients with a strong desire to preserve the anus, if the tumor has not invaded the external sphincter or levator muscles[2]. Compared with abdominoperineal resection (APR), ISR can achieve adequate distal resection margins (DRMs), sufficient circumferential resection margins (CRMs), and better anal function without permanent colostomy[3,4].

As an important surgical technique in the treatment of ultralow rectal cancer, laparoscopic ISR (LsISR) surgery has been widely applied in an increasing number of patients; moreover, the failure patterns after ISR, especially local recurrence and distant metastasis, have drawn the attention of surgeons. A study from Japan[5] reported that the mortality and morbidity were relatively low, although the 5-year cumulative local recurrence rate after ISR was 11.5%, which was higher than that after APR (evaluated using propensity score matching); in addition, multivariate analysis revealed that the pT stage, pN stage, and level of ISR were independent risk factors for local recurrence. These factors have also been reported in other studies[6-9]. However, the conclusions drawn by the aforementioned studies on ISR were limited by either a small sample size or selection bias derived from different centers or surgeons. Therefore, it is vital to further identify the risk factors for local recurrence and distal metastasis in patients with ultralow rectal cancers undergoing LsISR, to improve oncological outcomes.

In this cohort study, we investigated the long-term oncological outcomes and failure patterns of LsISR performed by a single surgical team. Furthermore, we investigated the risk factors for local recurrence and distal metastasis to optimize comprehensive treatment such as neoadjuvant therapy and preoperative surgical planning.

We collected retrospective data of patients with rectal cancer who underwent LsISR from multicenter between January 2012 and October 2022. We included patients who underwent LsISR surgery with radically local cancer resection and in whom the lower margin of the tumor was 2.0-5.0 cm away from the AV. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Non-adenocarcinoma; and (2) Perioperative death. Multidisciplinary team meetings determined treatment strategies for each patient and the necessity of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT). The pelvic radiotherapy was administered as a long-course regimen using external beam radiation therapy at a total dose of 45-54 Gy, and 6-12 wk after the radiation therapy underwent surgery. All patients provided informed consent for this study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (Approval No. 17-116/1439).

Standard total mesorectal excision (TME) was performed to reach the anorectal junction, while carefully preserving the bilateral hypogastric nerves and neurovascular bundles. The intersphincteric plane between the puborectalis muscle and internal anal sphincter was carefully dissected under direct vision. The distal rectum was transected intracorporeally using a flexible linear stapler. If the distance was ≥ 2.0 cm, the specimen was removed via a low midline mini-laparotomy incision, the sigmoid was cut at approximately 10 cm proximal to the tumor, and a circular stapled end-to-end coloanal anastomosis was constructed. If the distal margin was < 2.0 cm, trans-anal dissection was performed. The specimen was then extracted via the anus, and proximal resection was performed using a 60 mm linear stapler. Finally, anastomosis was constructed manually[10,11]. Regardless of whether the anastomosis was stapled or hand-sewn, diverting ileostomy was routinely performed[12]. Intraoperative frozen section pathology was normally required to confirm the status of the DRM when the margin was < 1 cm or suspected to be positive.

We collected the basic clinical and pathological characteristics of patients, including sex, age, body mass index, nCRT, diabetes, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, tumor distance from the AV, differentiation status, tumor diameter, (y)pT stage, (y)pN stage, (y)pTNM (tumor node metastasis) stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 8th edition), anastomotic leakage, complications, and postoperative chemotherapy. Follow-up was performed every 3 mo for the first 2 years, every 6 mo for the next 3 years, and annually thereafter. At each visit, patients underwent physical examination, serum carcinoembryonic antigen level measurement, and abdominopelvic magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography. Colonoscopy was routinely performed annually after surgery. Positron emission tomography was performed when required. The primary endpoint of this study was the 3-year local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), whereas the secondary endpoints were the 3-year overall survival (OS) and 3-year distant recurrence-free survival (DMFS). Local recurrence was defined as tumor recurrence in the pelvic cavity, which was confirmed by histopathology or imaging. Distant metastasis was defined as tumor recurrence outside the pelvis.

The Chi-square, Fisher's exact test, or Pearson's correlation test was used to analyze differences between the primary and validation cohorts. Pearson's correlation is a measure of the linear relationship between two continuous random variables, simultaneously, categorical variables were compared with use of χ2 analysis. Fisher's exact test is applicable to cases where sample size n < 40 or theoretical frequency T < 1. When one of the expected frequencies is greater than 5, Chi-square test is considered as a statistical method. Variables with a P-value < 0.100 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate analyses. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the risk factors were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression. All statistical analyses were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. R software (version 4.0.2) and SPSS software (version 25.0) were used for the statistical analyses.

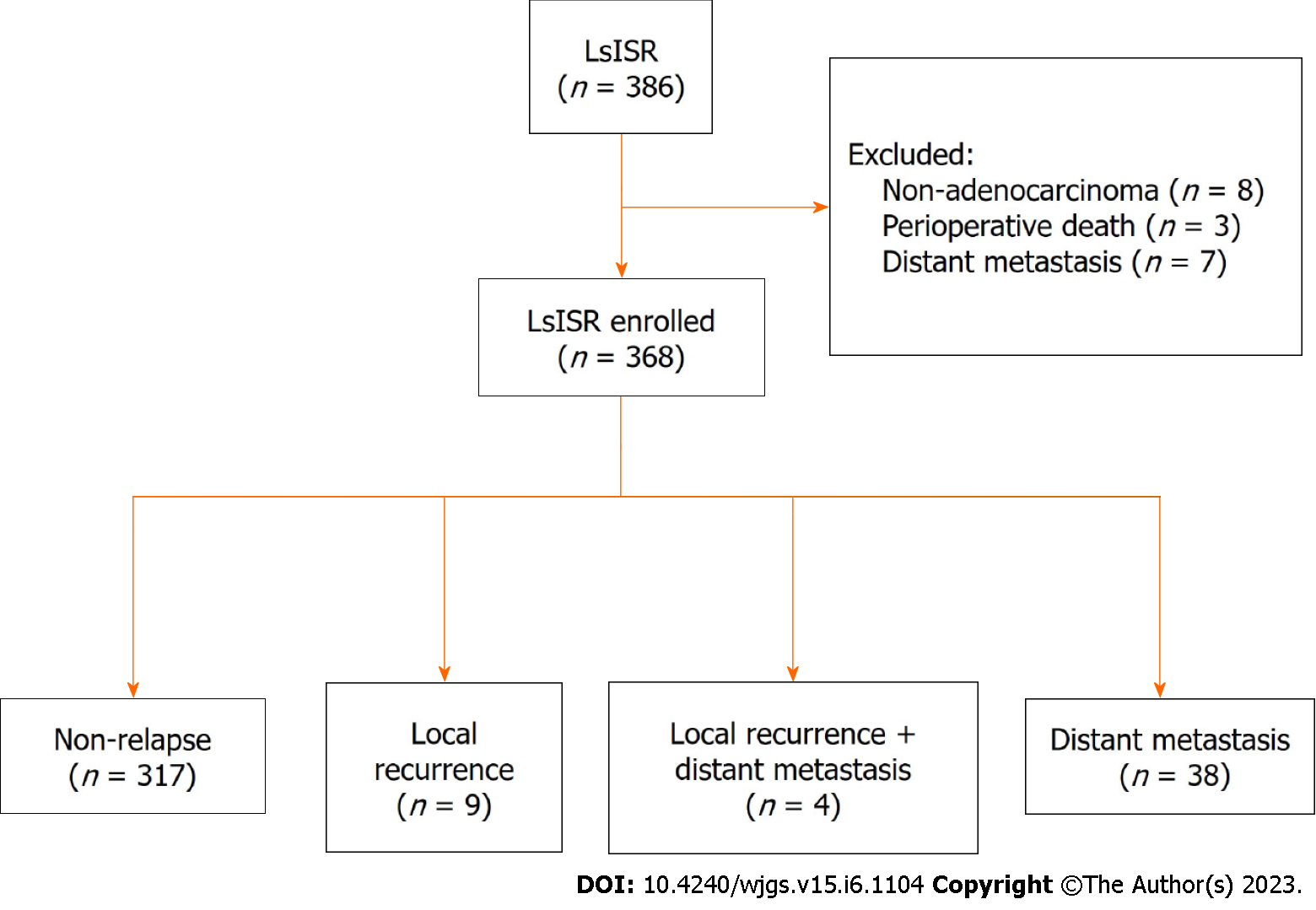

Data were obtained from a prospectively collected database of 386 consecutive patients who underwent LsISR. We excluded seven patients with distal metastasis and eight patients with non-adenocarcinoma as well as three patients who died perioperatively. Therefore, 368 patients were enrolled in this study (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the whole cohort, local recurrence group, non-local recurrence group, distant metastasis group, and non-distant metastasis group. In the whole cohort, proportions of T stage were: (y)pT1 (43, 11.9%), (y)pT2 (123, 33.7%), and (y)pT3 (202, 54.4%). Additionally, 121 patients (32.9%) had lymph node metastases. The median distance between the lower edge of the tumor and the AV was 4.0 cm (range, 2.0-5.0 cm), and the median distance between the anastomosis and the AV was 2.2 cm (range, 1.0-4.0 cm).

| Variables | Total (n = 368) | Local recurrence | Non-local recurrence (n = 355) | P value | Distant metastasis | Non-distant metastasis (n = 327) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 0.746 | 0.325 | |||||

| ≤ 60 | 184 (50) | 5 (38.5) | 179 (50.3) | 18 (42.9) | 167 (51.1) | ||

| > 60 | 184 (50) | 8 (61.5) | 176 (49.7) | 24 (57.1) | 160 (48.9) | ||

| Sex | 0.855 | 0.179 | |||||

| Male | 228 (62.0) | 8 (61.5) | 220 (61.9) | 30 (71.4) | 198 (60.7) | ||

| Female | 140 (38.0) | 5 (38.5) | 135 (38.1) | 12 (28.6) | 128(39.3) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.845 | 0.503 | |||||

| ≤ 25 | 246 (66.8) | 8 (61.5) | 238 (66.9) | 30 (71.4) | 217 (66.4) | ||

| > 25 | 122 (33.2) | 5 (38.5) | 117 (33.1) | 12 (28.6) | 110 (33.6) | ||

| Hb (g/L) | 0.204 | 0.123 | |||||

| Normal | 338 (91.8) | 12 (92.3) | 326 (91.8) | 36 (85.7) | 303 (92.7) | ||

| Abnormal | 30 (8.2) | 1 (7.7) | 29 (8.2) | 6 (14.3) | 24 (7.3) | ||

| Alb (g/L) | 0.756 | 0.058 | |||||

| ≥ 35 | 353 (95.9) | 12 (92.3) | 341 (96.0) | 38 (90.5) | 316 (96.6) | ||

| < 35 | 15 (4.1) | 1 (7.7) | 14 (4.0) | 4 (9.5) | 11 (3.4) | ||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.338 | 0.100 | |||||

| ≤ 5 | 267 (72.6) | 8 (61.5) | 259 (72.9) | 26 (61.9) | 242 (74.0) | ||

| > 5 | 101 (27.4) | 5 (38.5) | 96 (27.1) | 16 (38.1) | 85 (26.0) | ||

| CA 19-9 (u/mL) | 0.739 | 0.045 | |||||

| ≤ 37 | 350 (95.1) | 11 (84.6) | 339 (95.5) | 35 (83.3) | 316 (96.6) | ||

| > 37 | 18 (4.9) | 2 (15.4) | 16 (4.5) | 7 (16.7) | 11 (3.4) | ||

| Tumor height from anal verge (cm) | 0.985 | 0.053 | |||||

| ≤ 4 | 273 (74.2) | 10 (76.9) | 243 (68.4) | 26 (61.9) | 248 (75.8) | ||

| > 4 | 95 (25.8) | 3 (23.1) | 112 (31.6) | 16 (38.1) | 79 (24.2) | ||

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.465 | 0.590 | |||||

| ≤ 40 | 250 (67.9) | 7 (53.8) | 243 (68.4) | 27 (64.3) | 224 (68.2) | ||

| > 40 | 118 (32.1) | 6 (46.2) | 112 (31.6) | 15 (35.7) | 103 (31.8) | ||

| (y)pT stage | 0.198 | < 0.001 | |||||

| 1-2 | 166 (45.1) | 4 (30.8) | 162 (46.0) | 8 (19.0) | 158 (48.7) | ||

| 3 | 202 (54.9) | 9 (69.2) | 193 (54.0) | 34 (81.0) | 168 (51.3) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 245 (66.6) | 3 (23.1) | 242 (68.4) | 16 (38.1) | 230 (70.6) | ||

| Yes | 123 (33.4) | 10 (76.9) | 113 (31.6) | 26 (61.9) | 96 (29.4) | ||

| (y)p TNM stage | 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| 0-II | 245 (66.6) | 3 (23.1) | 242 (68.4) | 16 (35.6) | 231 (70.6) | ||

| III | 123 (33.4) | 10 (76.9) | 113 (31.6) | 26 (64.4) | 95 (29.4) | ||

| ASA score | 0.084 | 0.467 | |||||

| I-II | 357 (97.0) | 12 (92.3) | 345 (97.5) | 40 (95.2) | 317 (97.2) | ||

| III | 11 (3.0) | 1 (7.7) | 10 (2.5) | 2 (4.8) | 9 (2.8) | ||

| Differentiation | 0.009 | 0.070 | |||||

| Well-moderate | 328 (89.1) | 8 (61.5) | 320 (90.1) | 34 (81.0) | 294 (90.2) | ||

| Poor | 40 (10.9) | 5 (38.5) | 35 (9.9) | 8 (19.0) | 32 (9.8) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.054 | 0.021 | |||||

| No | 315 (85.6) | 9 (69.2) | 306 (86.4) | 31 (73.8) | 284 (87.2) | ||

| Yes | 53 (14.4) | 4 (30.8 | 49 (13.6) | 11 (26.2) | 42 (12.8) | ||

| Nerve invasion | 0.093 | 0.012 | |||||

| No | 327 (88.9) | 9 (69.2) | 318 (89.5) | 32 (76.2) | 295 (90.5) | ||

| Yes | 41 (11.1) | 4 (30.8) | 37 (10.5) | 10 (23.8) | 31 (9.5) | ||

| nCRT | 0.324 | 0.410 | |||||

| No | 328 (89.1) | 10 (76.9) | 318 (89.6) | 39 (92.9) | 289 (88.7) | ||

| Yes | 40 (10.9) | 3 (23.1) | 37 (10.4) | 3 (7.1) | 37 (11.3) | ||

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.137 | 0.378 | |||||

| No | 190 (51.6) | 4 (30.8) | 186 (52.5) | 19 (45.2) | 171 (52.5) | ||

| Yes | 178 (48.4) | 9 (69.2) | 169 (47.5) | 23 (54.8) | 155 (47.5) | ||

Local recurrence occurred in 13 patients (3.5%). In the analyses of basic characteristics between the local and non-local recurrence groups, there were significant differences in the distribution of pathological TNM stage (P = 0.001), lymph node status (P = 0.001), and differentiation (P = 0.009). Distant metastasis occurred in 42 (11.4%) patients. Compared with the patients without distant metastasis, the distant metastasis cohorts have higher serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level (P = 0.045), more advanced (y)pT stage (P < 0.001), (y)pN stage (P < 0.001), and (y)p TNM stage (P = 0.001), and the distant metastasis cohorts suffered lymphovascular invasion (P = 0.021) and nerve invasion (P = 0.012) tested in the postoperative pathological results.

The median follow-up times for the whole cohort, local recurrence group, and distant metastasis group were 42, 40, and 43 mo, respectively. The clinical demographics of the 13 (3.5%) patients who developed local recurrence are shown in Table 2, including 9 (69.2%) and 4 (30.8%) patients with anastomotic recurrence and pelvic lymph node metastasis, respectively. Most of the patients with local recurrence had (y)pT3 stage (10/13, 76.9%) and lymph node metastasis (10/13, 76.9%). Three (3/13, 23.1%) patients received preoperative nCRT, and 10 (10/13, 76.9%) patients underwent adjuvant therapy.

| N | Age | Sex | BMI | (y)pT | (y)pN | AV | AT | nCRT | Adjuvant therapy | Recurrence location |

| 1 | 46 | Female | 20.2 | 3 | 1b | 2 | 4 | No | Yes | Lateral and retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

| 2 | 70 | Female | 23.6 | 3 | 2b | 2 | 4 | No | Yes | Axial |

| 3 | 63 | Male | 25.5 | 1 | 2b | 3 | 4.5 | Yes | No | Lateral and retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

| 4 | 65 | Female | 23.4 | 3 | 2b | 2 | 4 | No | Yes | Lateral and retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

| 5 | 56 | Male | 18.0 | 2 | 0 | 1.5 | 3 | No | No | Axial |

| 6 | 69 | Male | 25.0 | 3 | 2a | 3 | 5 | No | Yes | Axial |

| 7 | 35 | Male | 32.6 | 3 | 0 | 1.5 | 3 | No | No | Axial |

| 8 | 55 | Male | 22.8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | No | No | Axial |

| 9 | 66 | Male | 27.4 | 3 | 2b | 2 | 4 | No | Yes | Axial |

| 10 | 64 | Male | 25.1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Axial |

| 11 | 51 | Female | 22.2 | 3 | 2b | 1.5 | 3 | No | Yes | Lateral and retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

| 12 | 82 | Female | 21.5 | 1 | 1b | 3 | 5 | No | Yes | Axial |

| 13 | 50 | Male | 25.6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | Yes | Yes | Axial |

Distant metastasis occurred in 42 (11.4%) patients, 4 (1.1%) of whom had both local recurrence and distant metastases. The most common distant metastatic sites were the lungs (20/42, 47.6%), liver (9/42, 21.4%), bones (4/42, 9.5%), and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (4/42, 9.5%).

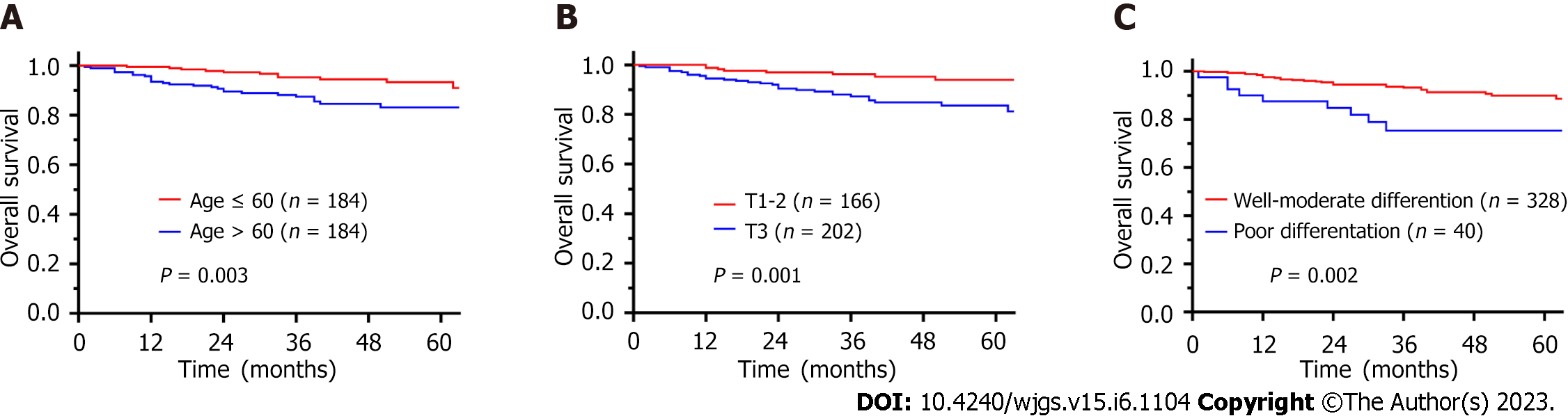

The OS rate at 1, 3, and 5 years were 96.5%, 91.3%, and 87.0%, respectively. Univariate analysis revealed that age > 60 years (HR = 2.776, 95%CI: 1.371-5.582, P = 0.004), nerve invasion (HR = 2.596, 95%CI: 1.186-5.683, P = 0.017), (y)pT3 stage (HR = 3.362, 95%CI: 1.541-7.336, P = 0.002), lymph node metastasis (HR = 2.304, 95%CI: 1.218-4.357, P = 0.010) and poor differentiation (HR = 3.117, 95%CI: 1.472-6.600, P = 0.003) were prognostic factors for OS (Table 3). Multivariate analyses demonstrated that age > 60 years (HR = 2.698, 95%CI: 1.329-5.489, P = 0.006), (y)pT3 stage (HR = 2.293, 95%CI: 1.006-5.226, P = 0.048) and poor differentiation (HR = 2.234, 95%CI: 1.021-4.887, P = 0.044) were independent prognostic factors for OS. Figure 2 shows the survival curves for OS according to age, (y)pT stage, and (y)pN stage.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (>60/ ≤ 60 yr) | 2.766 | 1.371–5.582 | 0.004 | 2.698 | 1.329–5.489 | 0.006 |

| Sex (female/male) | 0.713 | 0.359–1.415 | 0.333 | |||

| BMI (> 25/≤ 25 kg/m2) | 0.921 | 0.465–1.862 | 0.813 | |||

| CEA (> 5/≤ 5 ng/mL) | 1.350 | 0.690–2.639 | 0.381 | |||

| Tumor size (> 40/≤ 40 mm) | 1.425 | 0.742–2.733 | 0.287 | |||

| Tumor height from anal verge (cm) | 1.499 | 0.767–2.931 | 0.236 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion (yes/no) | 1.768 | 0.808–3.867 | 0.154 | |||

| Nerve invasion (yes/no) | 2.596 | 1.186–5.683 | 0.017 | 1.501 | 0.660–3.414 | 0.332 |

| (y)p T stage (3/1-2) | 3.362 | 1.541–7.336 | 0.002 | 2.293 | 1.006–5.226 | 0.048 |

| Lymph node metastasis (yes/no) | 2.304 | 1.218–4.357 | 0.010 | 1.713 | 0.878–3.339 | 0.114 |

| Differentiation (poor/well-moderate) | 3.117 | 1.472–6.600 | 0.003 | 2.234 | 1.021–4.887 | 0.044 |

| nCRT (yes/no) | 0.525 | 0.126–2.185 | 0.376 | |||

| Adjuvant therapy (yes/no) | 1.176 | 0.622–2.224 | 0.617 | |||

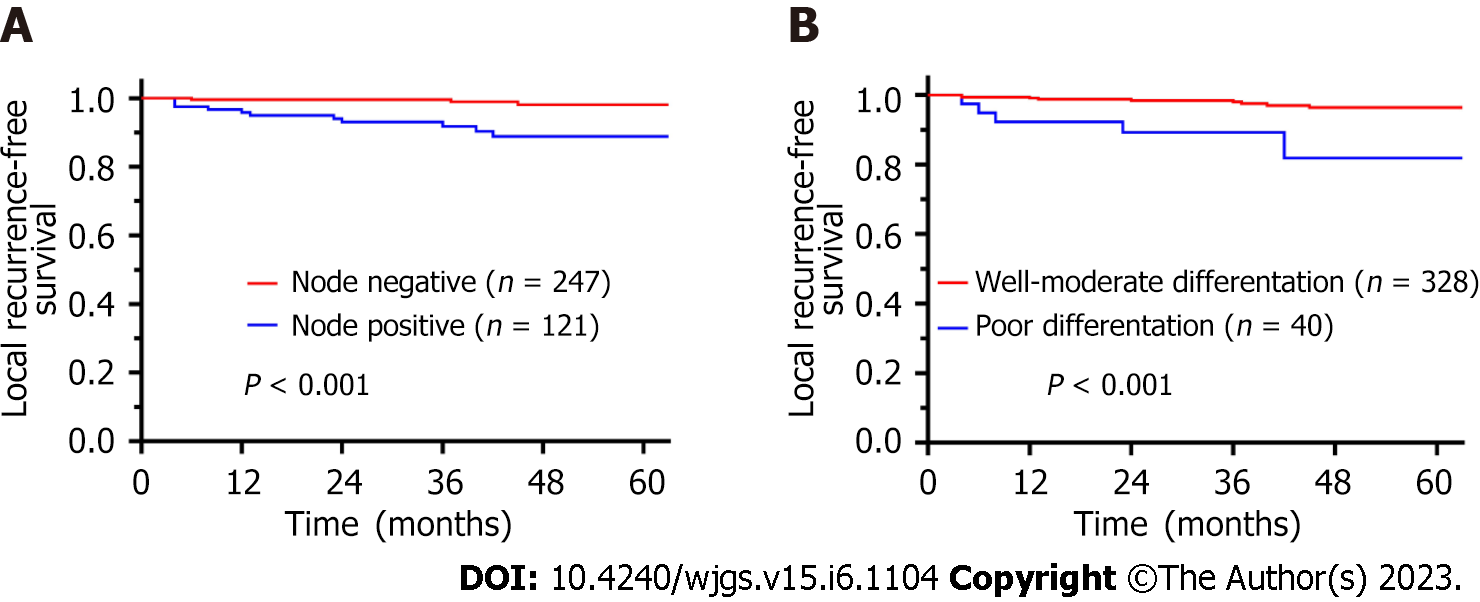

The LRFS rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 98.4%, 97.1%, and 95.4%, respectively. Table 4 shows the univariate and multivariate analyses findings for LRFS. In the univariate analysis, lymph node metastasis (HR = 6.984, 95%CI: 1.922-25.385, P = 0.003) and poor differentiation (HR = 6.293, 95%CI: 2.048-19.334, P = 0.001) were prognostic factors for LRFS. In the multivariate analysis, lymph node metastasis (HR = 5.358, 95%CI: 1.398-20.532, P = 0.014) and poor differentiation (HR = 3.908, 95%CI: 1.137-13.420, P = 0.030) remained independent prognostic factors for LFRS. The LRFS curves according to (y)pN stage and differentiation are shown in Figure 3.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (> 60/ ≤ 60 yr) | 1.318 | 0.442–3.931 | 0.620 | |||

| Sex (female/male) | 0.969 | 0.317–2.963 | 0.956 | |||

| BMI (> 25/≤ 25 kg/m2) | 1.263 | 0.413–3.860 | 0.683 | |||

| CEA (> 5/≤ 5 ng/mL) | 1.639 | 0.536–5.010 | 0.386 | |||

| Tumor size (> 40/≤ 40 mm) | 1.8332 | 0.615–5.451 | 0.277 | |||

| Tumor height from anal verge (cm) | 0.869 | 0.239–3.158 | 0.831 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion (yes/no) | 2.897 | 0.889–9.436 | 0.077 | 1.056 | 0.287–3.884 | 0.935 |

| Nerve invasion (yes/no) | 2.812 | 0.771–10.258 | 0.117 | |||

| (y)p T stage (3/1-2) | 1.982 | 0.610–6.438 | 0.255 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis (yes/no) | 6.984 | 1.922–25.385 | 0.003 | 5.358 | 1.398–20.532 | 0.014 |

| Differentiation (poor/well-moderate) | 6.293 | 2.048–19.334 | 0.001 | 3.908 | 1.137–13.420 | 0.030 |

| nCRT (yes/no) | 2.731 | 0.750–9.940 | 0.127 | |||

| Adjuvant therapy (yes/no) | 2.357 | 0.726–7.653 | 0.154 | |||

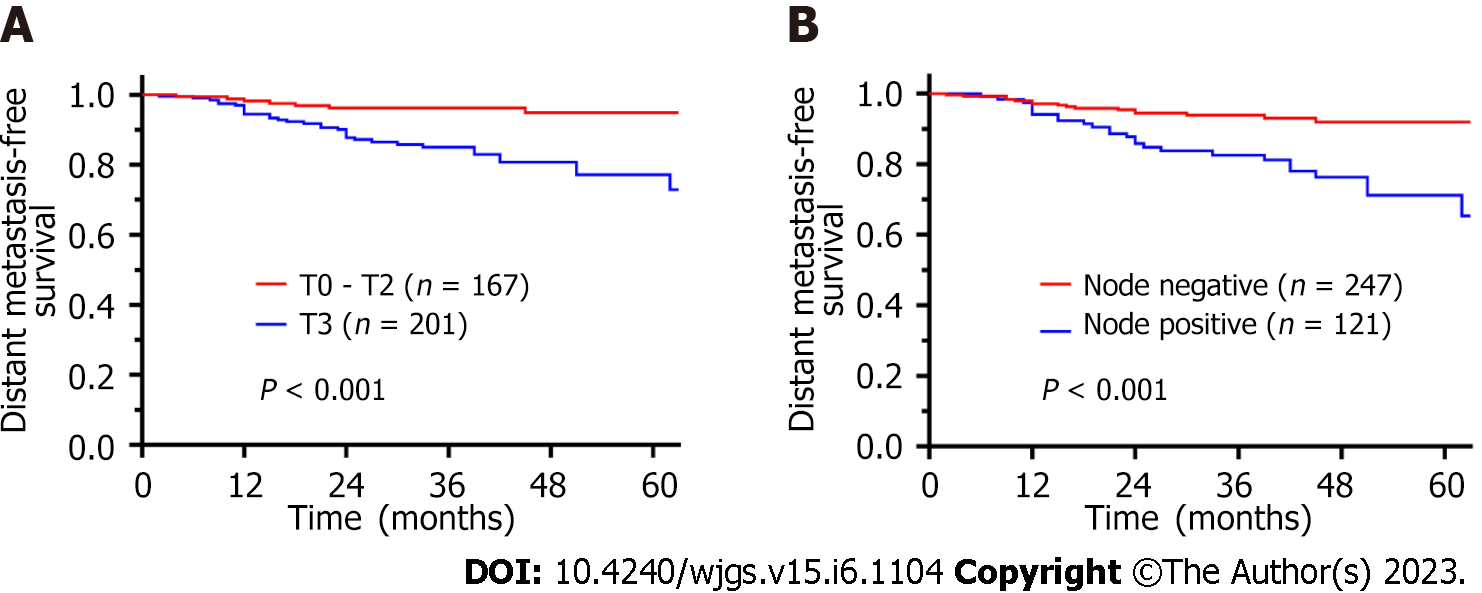

The DMFS rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 96.1%, 90.1%, and 82.6%, respectively. Table 5 shows risks factors for distant metastasis after ISR as identified via univariate and multivariate analyses. In the univariate analysis, lymphovascular invasion (HR = 2.527, 95%CI: 1.263-5.055, P = 0.009), nerve invasion (HR = 3.061, 95%CI: 1.499-6.252, P = 0.002), (y)pT3 stage (HR = 3.912, 95%CI: 1.810-8.456, P < 0.001), lymph node metastasis (HR = 3.410, 95%CI: 1.829-6.358, P < 0.001), and poor differentiation (HR = 2.451, 95%CI: 1.130-5.314, P = 0.023) were prognostic factors for DMFS. In the Multivariate analysis, pT3 stage (HR = 2.741, 95%CI: 1.225-6.137, P = 0.014) and lymph node metastasis (HR = 2.445, 95%CI: 1.272-4.698, P = 0.007) were independent prognostic factors for DMFS. Survival curves are shown in Figure 4.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (> 60/ ≤ 60 yr) | 1.506 | 0.817–2.779 | 0.190 | |||

| Sex (female/male) | 0.597 | 0.305–1.168 | 0.132 | |||

| BMI (> 25/≤ 25 kg/m2) | 0.783 | 0.401–1.530 | 0.474 | |||

| CEA (> 5/≤ 5 ng/mL) | 1.577 | 0.846–2.940 | 0.152 | |||

| Tumor size (> 40/≤ 40 mm) | 1.685 | 0.779–3.642 | 0.185 | |||

| Tumor height from anal verge (cm) | 1.685 | 0.779–3.642 | 0.185 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion (yes/no) | 2.527 | 1.263–5.055 | 0.009 | 1.128 | 0.508–2.506 | 0.767 |

| Nerve invasion (yes/no) | 3.061 | 1.499–6.252 | 0.002 | 1.644 | 0.745–3.628 | 0.218 |

| (y)p T stage (3/1-2) | 3.912 | 1.810–8.456 | 0.001 | 2.741 | 1.225–6.137 | 0.014 |

| Lymph node metastasis (yes/no) | 3.410 | 1.829–6.358 | < 0.001 | 2.445 | 1.272–4.698 | 0.007 |

| Differentiation (poor/well-moderate) | 2.451 | 1.130–5.314 | 0.023 | 1.446 | 0.634–3.301 | 0.381 |

| nCRT (yes/no) | 0.718 | 0.222–2.326 | 0.581 | |||

| Adjuvant therapy (yes/no) | 1.299 | 0.708–2.386 | 0.398 | |||

In recent years, anus-preserving surgery for ultralow rectal cancer and risk factors for postoperative recurrence and metastasis after ISR have been of concern. The failure patterns and predictors of local recurrence and distant metastasis after LsISR require further investigation. In this study, we found that local recurrence and distant metastasis occurred in 3.5% and 11.4% of patients, respectively. The OS/LRFS/DMFS rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 96.5%/91.3%/87.0%, 98.4%/97.1%/95.4%, and 96.1%/90.1%/82.6%, respectively. LRFS was associated with lymph node metastasis and poor differentiation, whereas the independent prognostic factors for DMFS were lymph node metastasis and (y)pT3 stage. To the best of our knowledge, this study hitherto includes the largest sample of patients who underwent LsISR performed by a single surgical team. Therefore, it can minimize the influence of surgeons on surgical quality and subsequently prognostic outcome, so as to better clarify the prognostic characteristics of this disease itself. In this study, we focused on failure patterns, including local recurrence and distal metastasis.

Previous studies mostly confirmed and compared the oncological safety of ISR and APR. A study from the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum nationwide registry, including 2125 patients who underwent ISR, reported that the mortality and morbidity were relatively low, and the survivals were relatively better compared with those of patients who underwent APR (5-year OS, 85.4% vs 74.8%, P < 0.001; 5-year LRFS, 70.5% vs 60.6%, P < 0.001); furthermore, the 5-year cumulative local recurrence rate after ISR was 11.5%[5]. Kim et al[13] compared the survival rates between patients who underwent low anterior resection and ISR. In the ISR group, the 5-year cumulative local and systemic recurrence rates were 2.4% and 15.1%, respectively, and no significant differences were observed between the two groups after propensity score matching (n = 166 each). The two groups had similar 5-year cumulative disease-free survival (78.5% vs 81.6%, P = 0.88) and OS (83.6% vs 90.8%, P = 0.65) rates. A meta-analysis including 2438 patients indicated that ISR could be a safe alternative to APR and could achieve oncological results similar to those of APR[14]. We considered that the oncological outcomes of ISR were related to many factors such as surgeon experience and skills, patient condition, malignancy and clinical tumor staging, as well as neoadjuvant chemoradiation. In this study, we enrolled patients operated by a single surgical team, to minimize selection bias. The long-term oncological outcomes and risk factors were analyzed. Although the oncological outcomes were not compared with those of APR, outcomes including the 5-year OS (87.0%), 5-year LRFS (95.4%), and 5-year cumulative local recurrence rate (4.6%) after LsISR in this cohort were similar to those previously reported.

Local recurrence, especially anastomotic recurrence, is one of the most important failure patterns of ISR. The 5- year cumulative local recurrence rate could still range from 2.4% to 15.7%, even in the patient with negative DRMs or CRMs in the initial surgery[6,13,15-18]. Previous studies reported that advanced T stage, lymph node metastasis, tumor size, nerve invasion, and lymphovascular invasion are risk factors for local recurrence after ISR[6-8,19,20]. Our study further confirmed that age > 60 years, (y)pT3 stage, and poor differentiation were independent prognostic factors for OS, whereas lymph node metastasis and poor differentiation were prognostic factors for LFRS. In patients with poorly differentiated tumors, submucosal infiltration or adjacent tumor nodules may occur, which would promote local recurrence of the anastomosis, despite a negative DRM. In patients with positive mesenteric lymph nodes, postoperative lateral lymph node metastasis may occur as another manifestation of pelvic recurrence. All four patients with lateral lymph node metastasis in this study had stage III disease. Prognostic factors for DMFS were further explored, showing that (y)pT3 stage and lymph node metastasis were independent prognostic factors, which were similar to previously reported factors.

The exploration of perioperative strategies aimed at reducing the risk of recurrence and metastasis of rectal cancer has been a hot topic. Preoperative nCRT followed by proctectomy with TME is commonly accepted as the gold standard for treating locally advanced rectal cancer with strong evidence of decreasing local recurrence rate and improving disease-free survival[21-25]; moreover, total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) may potentially improve local control. However, T-downstaging did not decrease the local recurrence rate in a previous study[26], and data from the RAPIDO trial showed an increased local recurrence rate for patients undergoing TNT, despite having a higher pathologic complete remission rate[27]. In our study, 3 patients with local recurrence were treated with neoadjuvant therapy before surgery, and the recurrence rate of the patients receiving nCRT was higher than that of patients not receiving nCRT (7.5% vs 2.7%, P = 0.324), although the difference was not significant. The indications for ISR in this study were relatively broad, and eight cases (9.1%) with pT3N + locally advanced rectal cancers were finally proven to be locally recurrent. Whether the rule of a 1-cm DRM following nCRT could increase the risk of anastomotic recurrence remains controversial. For patients with a high risk of local recurrence (N + or poor differentiation), extended radical resection (such as APR instead of ISR) may be more effective.

This study had some limitations. First, although only patients operated by a single surgical team were enrolled in this study, selection bias was inevitable due to the retrospective nature of the study. Second, the median follow-up time was relatively short, and the 5-year survival may not reflect the actual results. Furthermore, the proportion of patients who underwent nCRT was relatively small. The effect of nCRT on LRFS and DMFS after ISR remains unelucidated, and a larger cohort with more patients receiving nCRT is needed in future studies. Nonetheless, this study had the largest sample size and a relatively good control of surgical quality; hence, the results can objectively reflect tumor characteristics on the failure patterns of ISR.

In conclusion, this study confirmed the oncological safety of LsISR for ultralow rectal cancers. Poor differentiation, (y)pT3 stage, and lymph node metastasis are independent risk factors for treatment failure, and thus patients with these factors should be carefully managed with optimal neoadjuvant therapy, and for patients with a high risk of local recurrence (N + or poor differentiation), extended radical resection (such as APR instead of ISR) may be more effective.

The failure patterns and risk factors for local recurrence and distant metastasis after laparoscopic intersphincteric resection (LsISR) surgery remain controversial and require further investigation.

To investigate the long-term outcomes and failure patterns after LsISR.

Patients with ultralow rectal cancer who underwent LsISR from multicenter between January 2012 and October 2022. We included patients who underwent LsISR surgery.

The Chi-square, Fisher's exact test, or Pearson's correlation test was used to analyze differences between the primary and validation cohorts. Variables with a P-value < 0.100 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate analyses. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of the risk factors were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression.

Local recurrence and distant metastasis occurred in 3.5% and 11.4% of patients, respectively. The overall survival/local recurrence-free survival/distance metastasis-free survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 96.5%/91.3%/87.0%, 98.4%/97.1%/95.4%, and 96.1%/90.1%/82.6%, respectively. LRFS was associated with (y)N + and poor differentiation, whereas the independent prognostic factors for DMFS were lymph node metastasis and (y)pT3 stage.

We confirmed that poor differentiation, (y)pT3 stage, and (y)Pn + were independent risk factors for treatment failure, and thus patients with these factors should be carefully managed with optimal neoadjuvant therapy and surgical strategies.

This research will help clarify the high recurrence risk patients and take up most appropriate perioperative treatment strategies.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dimofte GM, Romania; Herold Z, Hungary S-Editor: Liu GL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Xv Y, Fan J, Ding Y, Hu Y, Jiang Z, Tao Q. Latest Advances in Intersphincteric Resection for Low Rectal Cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:8928109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Martin ST, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review of outcomes after intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:603-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Chen H, Ma B, Gao P, Wang H, Song Y, Tong L, Li P, Wang Z. Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection versus an open approach for low rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mukkai Krishnamurty D, Wise PE. Importance of surgical margins in rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113:323-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yamada K, Saiki Y, Takano S, Iwamoto K, Tanaka M, Fukunaga M, Noguchi T, Nakamura Y, Hisano S, Fukami K, Kuwahara D, Tsuji Y, Takano M, Usuku K, Ikeda T, Sugihara K. Long-term results of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer in Japan. Surg Today. 2019;49:275-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Piozzi GN, Park H, Lee TH, Kim JS, Choi HB, Baek SJ, Kwak JM, Kim J, Kim SH. Risk factors for local recurrence and long term survival after minimally invasive intersphincteric resection for very low rectal cancer: Multivariate analysis in 161 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:2069-2077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Desouza AL, Kazi M, Verma K, Sugoor P, Mahendra BK, Saklani AP. Local recurrence with intersphincteric resection in adverse histology rectal cancers. A retrospective study with competing risk analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:2475-2481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shin JK, Kim HC, Lee WY, Yun SH, Cho YB, Huh JW, Park YA. Sphincter-saving surgery versus abdominoperineal resection in low rectal cancer following neoadjuvant treatment with propensity score analysis. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:2623-2630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim KH, Park MJ, Lim JS, Kim NK, Min BS, Ahn JB, Kim TI, Kim HG, Koom WS. Circumferential resection margin positivity after preoperative chemoradiotherapy based on magnetic resonance imaging for locally advanced rectal cancer: implication of boost radiotherapy to the involved mesorectal fascia. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:316-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chi P, Huang SH, Lin HM, Lu XR, Huang Y, Jiang WZ, Xu ZB, Chen ZF, Sun YW, Ye DX. Laparoscopic transabdominal approach partial intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: surgical feasibility and intermediate-term outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:944-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park JS, Choi GS, Jun SH, Hasegawa S, Sakai Y. Laparoscopic versus open intersphincteric resection and coloanal anastomosis for low rectal cancer: intermediate-term oncologic outcomes. Ann Surg. 2011;254:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Klink CD, Lioupis K, Binnebösel M, Kaemmer D, Kozubek I, Grommes J, Neumann UP, Jansen M, Willis S. Diversion stoma after colorectal surgery: loop colostomy or ileostomy? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim JC, Kim CW, Lee JL, Yoon YS, Park IJ, Kim JR, Kim J, Park SH. Complete intersphincteric longitudinal muscle excision May Be key to reducing local recurrence during intersphincteric resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:1629-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Peng B, Lu J, Wu Z, Li G, Wei F, Cao J, Li W. Intersphincteric Resection Versus Abdominoperineal Resection for Low Rectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Surg Innov. 2020;27:392-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Akasu T, Takawa M, Yamamoto S, Fujita S, Moriya Y. Incidence and patterns of recurrence after intersphincteric resection for very low rectal adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:642-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen ZH, Song XM, Chen SC, Li MZ, Li XX, Zhan WH, He YL. Risk factors for adverse outcome in low rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim CH, Lee SY, Kim HR, Kim YJ. Factors Associated With Oncologic Outcomes Following Abdominoperineal or Intersphincteric Resection in Patients Treated With Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy: A Propensity Score Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koyama M, Murata A, Sakamoto Y, Morohashi H, Takahashi S, Yoshida E, Hakamada K. Long-term clinical and functional results of intersphincteric resection for lower rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S422-S428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Onaitis MW, Noone RB, Hartwig M, Hurwitz H, Morse M, Jowell P, McGrath K, Lee C, Anscher MS, Clary B, Mantyh C, Pappas TN, Ludwig K, Seigler HF, Tyler DS. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer: analysis of clinical outcomes from a 13-year institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2001;233:778-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim NK, Baik SH, Seong JS, Kim H, Roh JK, Lee KY, Sohn SK, Cho CH. Oncologic outcomes after neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by curative resection with tumor-specific mesorectal excision for fixed locally advanced rectal cancer: Impact of postirradiated pathologic downstaging on local recurrence and survival. Ann Surg. 2006;244:1024-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Abraha I, Aristei C, Palumbo I, Lupattelli M, Trastulli S, Cirocchi R, De Florio R, Valentini V. Preoperative radiotherapy and curative surgery for the management of localised rectal carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD002102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Putter H, Steup WH, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, van Krieken JH, Leer JW, van de Velde CJ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3104] [Cited by in RCA: 3116] [Article Influence: 129.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, Daban A, Bardet E, Beny A, Ollier JC; EORTC Radiotherapy Group Trial 22921. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1114-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1993] [Cited by in RCA: 2040] [Article Influence: 107.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gérard JP, Conroy T, Bonnetain F, Bouché O, Chapet O, Closon-Dejardin MT, Untereiner M, Leduc B, Francois E, Maurel J, Seitz JF, Buecher B, Mackiewicz R, Ducreux M, Bedenne L. Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4620-4625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1273] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Martin ST, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:918-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 517] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Iskander O, Courtot L, Tabchouri N, Artus A, Michot N, Muller O, Pabst-Giger U, Bourlier P, Kraemer-Bucur A, Lecomte T, Guyetant S, Chapet S, Calais G, Salamé E, Ouaïssi M. Complete Pathological Response Following Radiochemotherapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Short and Long-term Outcome. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:5105-5113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B, Marijnen CAM, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Roodvoets AGH, Nagtegaal ID, Beets-Tan RGH, Blomqvist LK, Fokstuen T, Ten Tije AJ, Capdevila J, Hendriks MP, Edhemovic I, Cervantes A, Nilsson PJ, Glimelius B, van de Velde CJH, Hospers GAP; RAPIDO collaborative investigators. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:29-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 237.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |