Published online Apr 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i4.534

Peer-review started: November 29, 2022

First decision: December 26, 2022

Revised: January 10, 2023

Accepted: March 21, 2023

Article in press: March 21, 2023

Published online: April 27, 2023

Processing time: 144 Days and 22.5 Hours

Acute pancreatitis (AP) has varying severity, and moderately severe and severe AP has prolonged hospitalization and requires multiple interventions. These patients are at risk of malnutrition. There is no proven pharmacotherapy for AP, however, apart from fluid resuscitation, analgesics, and organ support, nutrition plays an important role in the management of AP. Oral or enteral nutrition (EN) is the preferred route of nutrition in AP, however, in a subset of patients, parenteral nutrition is required. EN has various physiological benefits and decreases the risk of infection, intervention, and mortality. There is no proven role of probiotics, glutamine supplementation, antioxidants, and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in patients with AP.

Core Tip: Nutrition improves the outcomes of acute pancreatitis (AP). In mild AP, solid food can be given when the patient is pain-free and hungry. In moderately severe and severe pancreatitis, feeding can begin as early as possible if there are no contraindications for an oral diet. If the patient does not tolerate an oral diet, tube feeding can be tried; and in case of gastric outlet obstruction or gastroparesis, nasojejunal tube feeding is preferred. Parenteral nutrition should be provided in case of complete intolerance or contraindications to oral/enteric feed or supplemented along with enteral feed if energy targets are not met.

- Citation: Gopi S, Saraya A, Gunjan D. Nutrition in acute pancreatitis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(4): 534-543

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i4/534.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i4.534

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an acute inflammatory condition of the pancreas, leading to systemic inflammation, organ failure, infection, morbidity, and mortality. It is a frequent cause of emergency visits and its incidence is rising globally[1]. AP is a catabolic state and malnutrition sets in early, progresses rapidly, and is associated with poor prognosis. The management of AP is centered on fluid resu

Among the patients of AP, nearly 80%-85% will have acute interstitial pancreatitis, usually with mild severity and no risk of mortality. Mild AP is usually self-limiting with an uncomplicated course. Patients do not have local complications or organ failure, and pain subsides early. A low-fat, soft oral diet can be initiated as early as possible when patients feel hungry and are pain-free. Compared with the stepwise introduction of diet from a liquid diet to an oral diet, a full-calorie solid oral food is similarly tolerated and is associated with better calorie intake and a shorter hospital stay[2-4].

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis occurs in 15%-20% of patients, which can be MSAP or SAP with a 5%-30% risk of mortality depending on organ failure and infective complications[5]. These MSAP and SAP will be associated with prolonged hospitalizations, infectious complications, requiring invasive interventions, malnutrition, morbidity, and mortality.

Studies on resting energy expenditure (REE) in AP are limited and have shown that most patients with severe AP and AP with sepsis are hypermetabolic based on gold standard indirect calorimetry (> 110% of predicted energy expenditure by Harris-Benedict equation)[6,7]. Hyperglycemia is often observed during AP and is related to pancreatic necrosis and infections. It is characterized by hyperglucagonemia and relative hypoinsulinemia in the early phase leading to increased gluconeogenesis, while relative hypoinsulinemia extends into the late phase also[8]. Hence, glucose monitoring and control are essential.

In necrotizing AP, severe inflammation in the early phase and sepsis in the later phase leads to increased protein catabolism[9]. In necrotizing AP, skeletal muscle mass and muscle density decrease significantly and rapidly within a month, and it was observed that a decrease in muscle density of ≥ 10% in 1 mo was an independent predictor of mortality[10]. There is increased lipolysis and impaired lipid clearance due to relative hypoinsulinemia and serum triglyceride levels require monitoring in those with severe hypertriglyceridemia as etiology of AP and those in intravenous lipid emulsions.

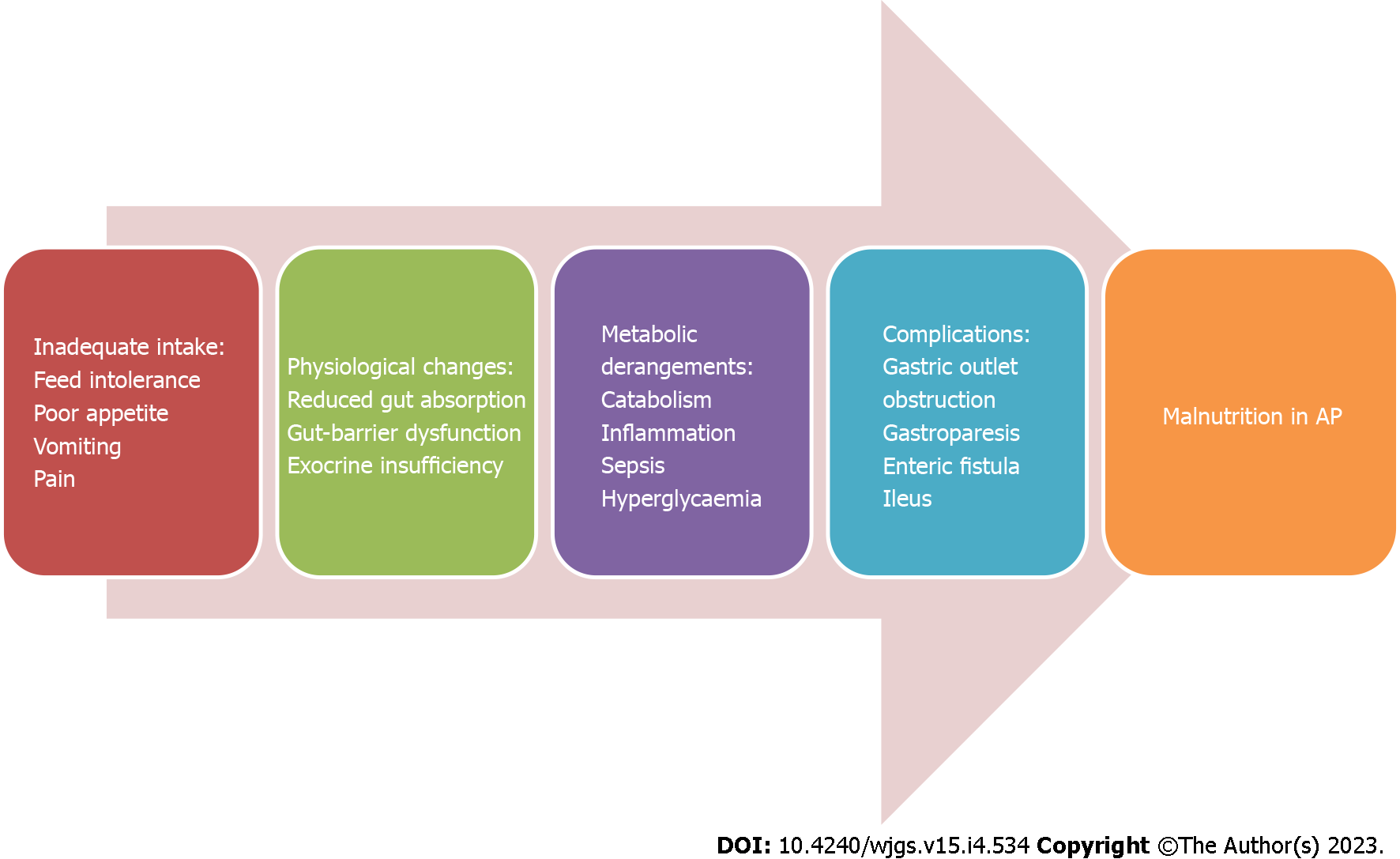

Malnutrition develops rapidly, is common, especially in necrotizing AP, and is multifactorial (Figure 1). The probable causes are: (1) Decreased oral intake due to pain, nausea and vomiting secondary to gastroparesis or gastric outlet obstruction, intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and inappropriate fasting; (2) Increased catabolism in severe AP, and AP with sepsis; (3) Alcoholism; (4) Intestinal failure due to ileus or enteric fistulas; and (5) Exocrine and endocrine dysfunction during AP[11].

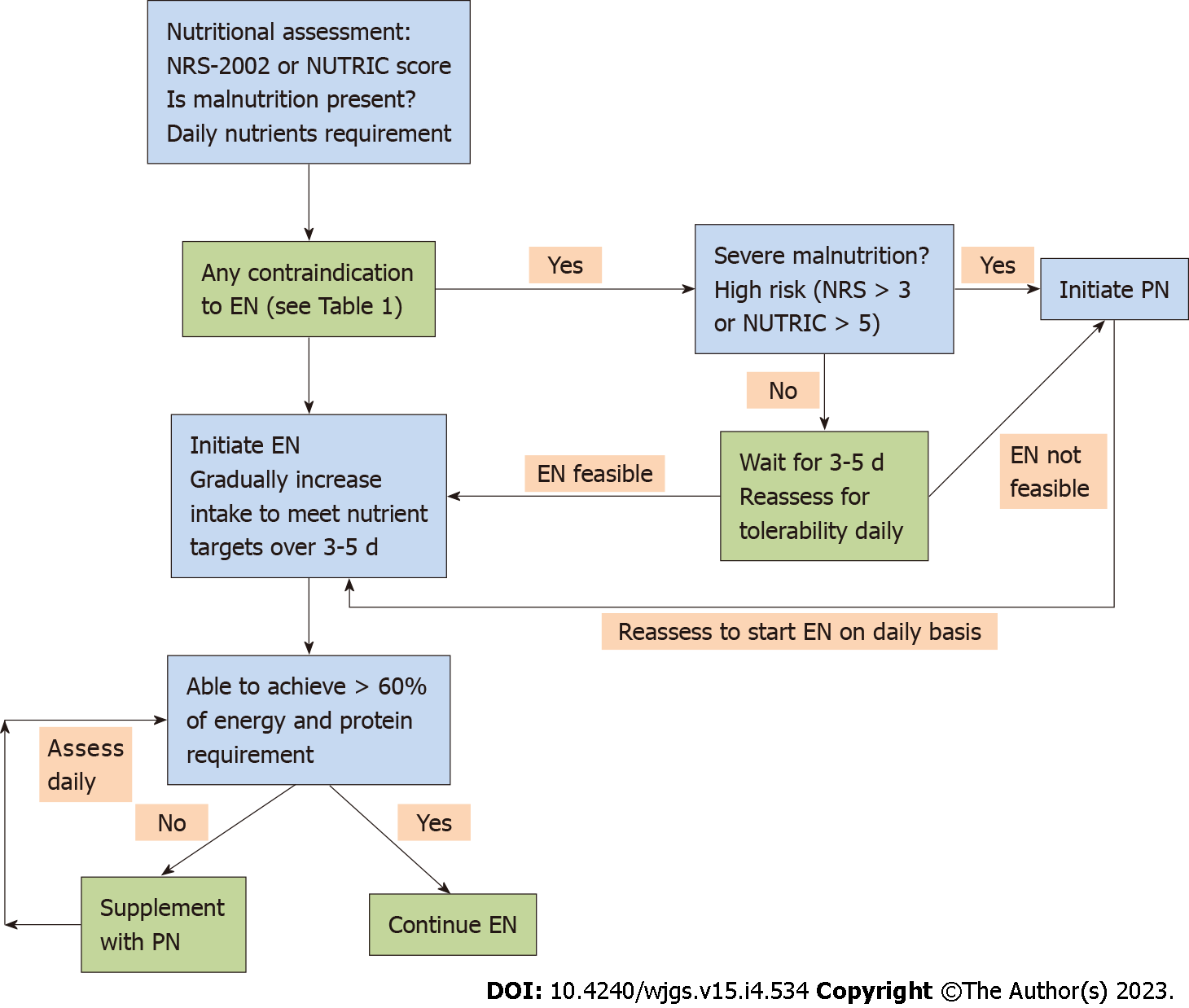

The purpose of nutritional assessment is to assess if a patient is at risk of malnutrition, and the current nutritional status of the patient and to plan personalized nutritional support for a patient depending on the severity of AP and the patient’s current clinical status. Nutritional risk is defined by the present nutritional status and risk of impairment of present status, due to increased requirements caused by stress metabolism of the clinical condition. All patients with predicted mild to moderate AP need to be screened using validated tools like nutritional risk screening (commonly known as NRS)-2002 or nutrition risk in the critically ill (commonly referred to as NUTRIC) score, and those with predicted severe AP need to be considered at nutritional risk with no screening[12]. This helps to identify patients at high nutrition risk, and these are more likely to benefit from early enteral nutrition (EN) with improved outcomes[13]. There are various definitions of the diagnostic criteria for malnutrition, and Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (commonly known as GLIM) criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition were proposed by major nutritional societies for a uniform definition globally[14]. Serum markers like albumin, pre-albumin, or transferrin should be avoided in nutritional assessment in AP, as those serum markers are not truly reflective of malnutrition[15].

Indirect calorimetry is the gold standard for the assessment of calorie requirement, especially in critically ill patients but rarely used given its limited availability. The predicted REE can be calculated using predictive equations like the Harris-Benedict equation or by a simpler weight-based equation of 25-30 kcal/kg/day[13]. In healthy adults, the Harris-Benedict equation can provide an approximate estimate of REE in kcal/day, and the same equation can be used for critically ill patients without any modification. Adjusted body weight is preferred for patients with obesity, edema, or ascites[16].

In those who are not critically ill, like mobile patients without organ failure, an additional 10%-20% of the calculated value from the equation is added to account for physical activity and thermogenesis. In patients who are not critically ill and with malnutrition like low BMI (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), an additional 300-500 kcal is added to improve their nutritional status[16]. The protein requirements are higher than the healthy controls given higher protein catabolism, especially in severe AP and AP with sepsis. Weight-based protein intake (1.2-2 g/kg/day) can be used to target daily protein requirements[13]. A mixed source of energy from carbohydrates, proteins, and fats is preferable. Micronutrients should be supplemented in patients with suspected or confirmed deficiencies, especially in patients with a history of chronic alcohol consumption or pre-existing malnutrition. In patients on total parenteral nutrition (PN), daily supplementation of multivitamins and trace elements is required as per the recommended daily allowances[11].

A proportion of patients with MSAP or SAP on tube feeding cannot tolerate a complete feed that achieves all calorie requirements owing to various reasons like pain, vomiting, and others[17]. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of critically ill patients, permissive underfeeding (40%-60% of estimated caloric requirements) as compared to standard enteral feeding (70%-100% of estimated caloric requirements) was found to have similar clinical outcomes like mortality, infections, and hospital stay with no serious adverse events. An important caveat in that study is that both groups received a similar protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg/day[18]. Hence, in critically ill patients who cannot tolerate entire calorie targets, we can continue with permissive underfeeding. In patients with poor tolerance to tube feeding or those on PN, trophic feeding, i.e. small-volume enteral feeding to stimulate the gut, not to meet the calorie requirements, may help to maintain the intestinal physiology, prevent mucosal atrophy, and improve gut barrier dysfunction[19].

An oral diet is preferred in patients who can take it orally. In patients, who are not able to feed orally, EN by tube feeding is preferred over PN[12]. In addition to meeting the nutritional targets, EN has additional advantages like beneficial gastrointestinal, immunological, and metabolic responses[20]. In conditions with contraindications to EN (Table 1), patients should be assessed for initiating PN (Figure 2)[21,22].

| Contraindications of EN |

| Uncontrolled shock (low dose EN can be initiated once the shock is controlled with fluids and vasopressors with close monitoring for any signs of bowel ischemia). |

| Uncontrolled hypoxemia, hypercapnia, or acidosis (EN can be initiated in patients with stable hypoxemia, and compensated or permissive hypercapnia and acidosis.) |

| Active upper gastrointestinal bleeding (EN can be initiated once bleeding is controlled) |

| Gastric aspirate of > 500 mL/6 h |

| Abdominal compartment syndrome or intra-abdominal pressure of > 20 mm Hg |

| Bowel obstruction or ileus |

| Bowel ischemia |

| High-output fistula without distal feeding access |

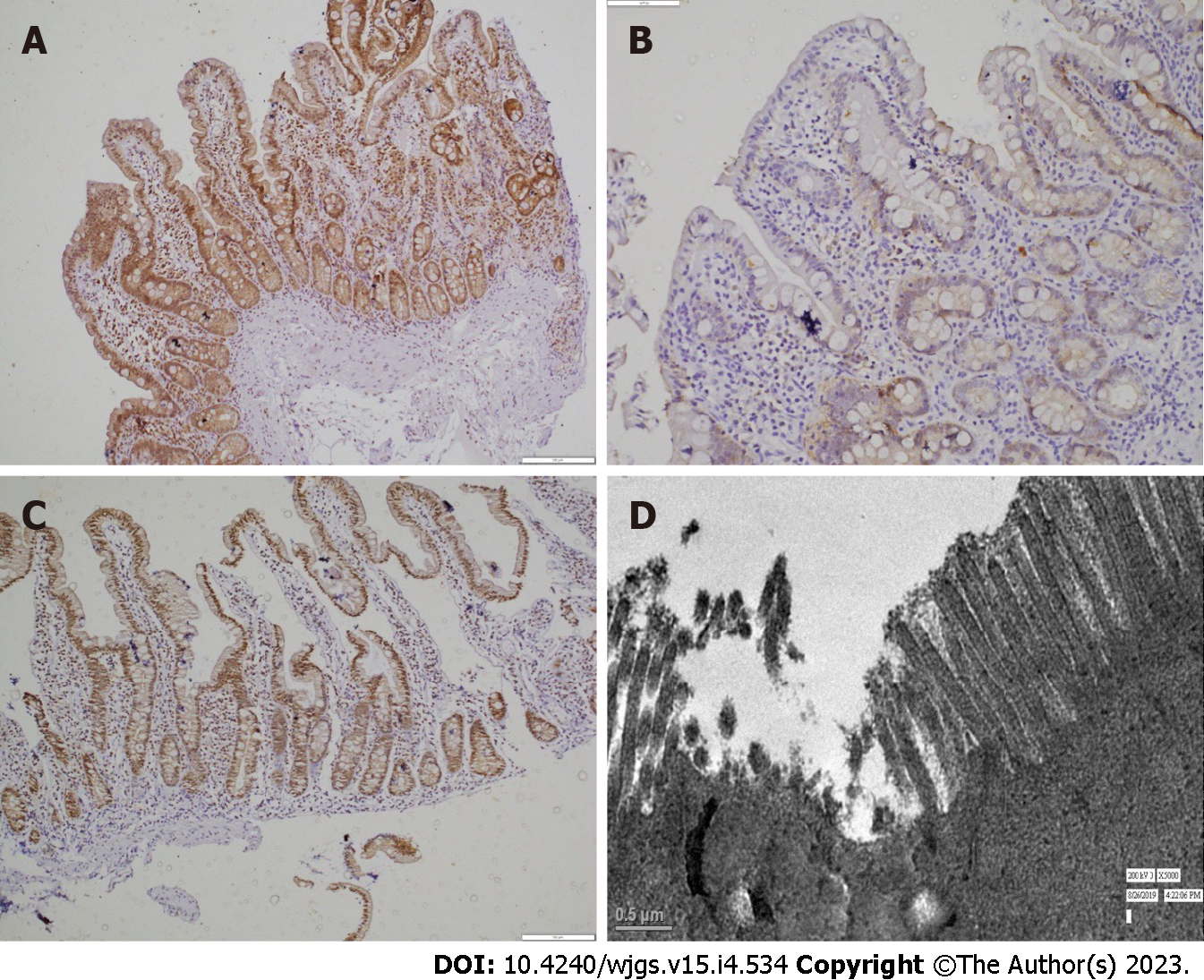

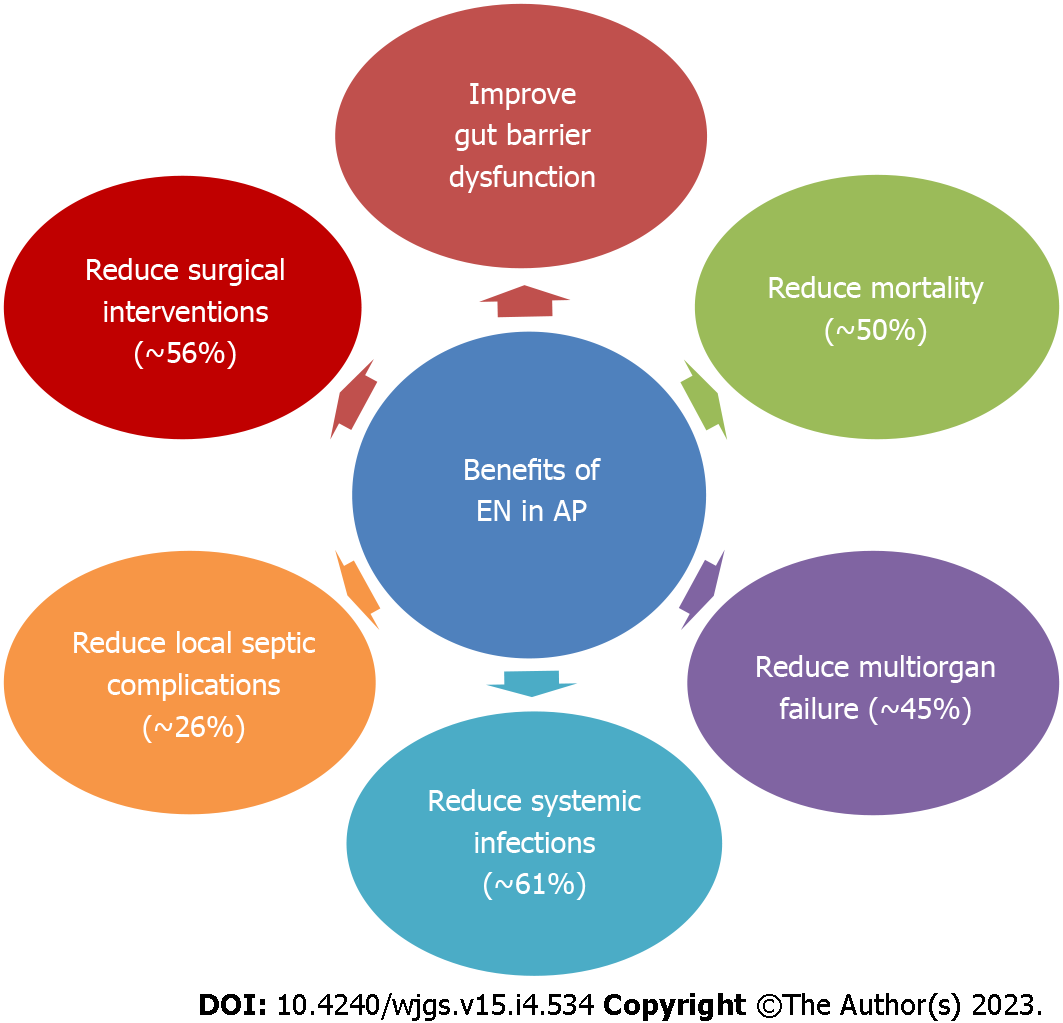

The earlier concept of “pancreatic rest” in AP by continuing patient fasting has fallen out of favor, as the benefits and safety of early EN in AP are now well established in RCTs[12,23]. The gut barrier dysfunction in AP is implicated in increased bacterial translocation and subsequent infection of pancreatic necrosis or collections. EN can improve gut barrier dysfunction and preserve the gut mucosal integrity, prevent bacterial translocation, stimulate gut motility, and improve splanchnic circulation[12,24,25] (Figure 3). EN is the recommended mode of nutritional support in AP. Compared with PN, EN decreases systemic infections, multiorgan failure, hospital stay, mortality, and the need for surgical interventions and the benefit is more pronounced in severe AP (Figure 4)[23,24,26,27].

EN must be started after adequate fluid resuscitation and at least a relatively stable hemodynamic status. Meta-analyses have shown that early EN started within 24-48 h of admission is feasible, tolerated, and associated with lower mortality, organ failure, and infections[28,29]. Two recent RCTs found no difference in mortality, organ failure, or infections between early EN started within 24 h or an oral diet started after 72 h of admission[30,31]. Another prospective cohort study observed that the 3rd d after hospital admission was the best cutoff to reduce infections, with better tolerance and nutritional improvement[32]. A possible explanation is that most of the patients in these two RCTs were not critically ill, and that the benefit of early EN is more pronounced in severe AP compared with other categories of severity[26]. Hence, patients who are not critically ill can be safely started on an oral diet when symptoms improve or an enteral diet, i.e. tube feeding, can be considered after admission if an oral diet is not tolerated. In critically ill patients not tolerating an oral diet, existing data suggest that the EN must be initiated within 48-72 h of admission[5,21]. A RCT is required to justify the benefits of early EN within 24-48 h in this specific group of critically ill patients.

EN can be provided by elemental or semi-elemental or polymeric diets. Elemental diets are completely predigested commercial formulations with the simplest form of nutrients. They contain simple carbohydrates and individual amino acids, are low in fat, and contain medium-chain triglycerides. Semi-elemental formulations are commercial feeds with partially predigested enteral formulations (simple carbohydrates, oligopeptides of varying length, and medium-chain triglycerides), whereas polymeric formulations have intact macronutrient components (complex carbohydrates, whole proteins, and long-chain triglycerides). Most earlier studies showing benefits with early EN compared with parental nutrition or no nutrition were done with a semi-elemental diet while some recent studies done with polymeric formulations also showed benefits[33-35]. A pilot RCT compared a semi-elemental diet with a polymeric diet and showed that both were similarly tolerated and absorbed while hospital stay and weight loss were lower with a semi-elemental diet[36]. A meta-analysis compared semi-elemental and polymeric formulations indirectly using PN as a reference and found that feeding tolerance, complications and mortality were similar in both groups[33]. Hence, the guidelines recommend a standard polymeric diet for EN in AP including critically ill patients[12,13].

A polymeric diet can be from two sources: commercial formulations and kitchen-based preparations. Commercial formulas became more desirable, as they are easy to prepare, less prone to microbial contamination, and provide the desired amount of nutrients. However, commercial formulations are more expensive and have less palatability compared with the kitchen-based diet. Kitchen-based diets are easily available, cost-effective in healthcare settings with limited resources, more palatable, and more acceptable to patients. The concerns of a kitchen-based diet are a long time in preparation, increased risk of microbiological contamination, and uncertainty on their nutritional value, especially with nonstandardized recipes[37,38]. In a recently conducted pilot RCT in patients with MSAP and SAP, we observed that both a kitchen-based diet and commercial polymeric formulations were similarly tolerated (personal communication). In summary, EN in any form is beneficial, and the choice should depend on the availability of formulations and cost.

Nasogastric tube feeding is cheaper, easier to insert, and convenient compared to nasojejunal tube feeding. Physiologically, the nasojejunal tube is thought to decrease pancreatic stimulation and secretion, and probably decrease pain and complications, but RCTs have found no differences between nasogastric and nasojejunal feeding in complication rate, refeeding pain, and hospital stay. A recent Cochrane review concluded that there is insufficient evidence to prove superiority or equivalence or inferiority of nasojejunal feeding over nasogastric feeding[39-42]. So, all patients who do not tolerate oral diet should be initiated on EN through the nasogastric or nasojejunal route. Nasojejunal tube feeding should be preferred if a patient has delayed gastric emptying, gastric outlet obstruction due to pancreatitis, or patients with high-risk of aspiration[21].

Although intermittent bolus feeding is physiological and has theoretical advantages, existing data showed an increased incidence of diarrhea with intermittent feeds without additional clinical benefit in critically ill patients[43]. Hence, continuous feeding is preferred over intermittent feeding in EN in critically ill patients, although direct evidence is not available in patients with AP.

Although EN is the preferred nutrition over PN in AP, the following are the indications for PN in AP (Figure 2): (1) Complete intolerance to EN; (2) Unable to meet nutritional targets with EN alone; and (3) Contraindication to EN.

Immuno-nutrition: (1) Glutamine: Glutamine, a nonessential amino acid, is essential for the survival, proliferation, and function of immune cells. During catabolic/hypercatabolic circumstances, the requirement for glutamine increases rapidly during hypercatabolic states and may lead to impairment of the immune function. A meta-analysis showed the benefit of glutamine supplementation by a reduction in infections, mortality, and hospital stay, and a subgroup analysis showed that those benefits were seen only in patients receiving PN and intravenous glutamine[44]. The risk of bias in the included studies was due to the small sample size and heterogeneity in the severity of the disease. According to European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines, intravenous L-glutamine at a dose of 0.2 g/kg/day should be given in patients on total PN owing to contraindications or nonfeasibility of EN[12]; and (2) Antioxidants: A meta-analysis assessed the effects of antioxidants (including glutamine and other antioxidants) and observed that the antioxidants resulted in a reduction in complications and hospital stay but not mortality[45]. As the results were attributed to glutamine, and a recent Cochrane review did not find any clinical benefit of antioxidants, guidelines do not recommend antioxidant mixtures in AP[12,46].

Probiotics: In experimental models of AP, probiotics were shown to decrease intestinal permeability and hence proposed to reduce infections and mortality[47]. However, in a meta-analysis of clinical trials on patients with AP, there was no benefit of probiotics on infections or mortality, and in one of the RCTs, a multispecies probiotic combination was associated with increased mortality compared to a placebo[48,49]. Currently there is no evidence to support the use of probiotics in AP and the guidelines do not recommend probiotics[12].

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy: In a meta-analysis, the prevalence of exocrine insufficiency in AP during admission was 65%, more commonly seen with severe AP and persisted during follow-up in 35% of cases[50]. In an RCT, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in AP did not show any statistically significant clinical benefit and only 35% of patients had exocrine insufficiency[51]. Although the data are inadequate, there may be a role of enzyme supplementation in AP with exocrine insufficiency to improve absorption and nutrition[12]. However, recent evidence does not support the generalized use of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) in patients with AP.

Normal intra-abdominal pressure is 5-7 mmHg in critically ill patients and IAH is diagnosed when intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) is increased to ≥ 12 mmHg. As most patients with IAH will have ileus, abdominal distension, or high gastric residue, EN can be initiated via the nasojejunal route in patients with IAH[12,52].

If the IAP is < 15 mmHg, early EN can be initiated preferably via the nasojejunal route or nasogastric tube. If the IAP > 15 mmHg, it is preferable to initiate the feed via the nasojejunal route with caution at a slow rate (20 mL/h) and increase it gradually, as tolerated, monitor IAP, and withhold EN if the pressure increases further. In case of an IAP of > 20 mmHg or presence of abdominal compartment syndrome, EN is to be avoided until the IAP reduces, and PN should be initiated[12]. In postoperative patients with an open abdomen, EN, if possible, is associated with mortality benefit, lesser complications, and higher fascial closure rates. Hence, EN should be initiated and tried at least in small amounts and rest supplemented by PN[12].

Oral nutrition or if not tolerated, EN is safe and can be initiated within the first 24 h after the procedure provided there are no other contraindications to EN[12].

In conclusion, AP is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Many patients require prolonged hospitalization, multiple interventions, and develop malnutrition. Nutritional supplementation is an important part of the armamentarium to improve the outcomes in patients with AP. Oral or EN is the preferred route and can be started as early as possible. In mild AP, an oral diet can be started whenever a patient is free of pain and feeling hungry. In MSAP and SAP, if oral feeding is not tolerated, then tube feeding can be initiated. However, some patients may require PN. There is no clear benefit of probiotics, immuno-nutrition, and PERT; and they should not be recommended based on current evidence.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shalaby MN, Egypt; Susak YM, Ukraine S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Iannuzzi JP, King JA, Leong JH, Quan J, Windsor JW, Tanyingoh D, Coward S, Forbes N, Heitman SJ, Shaheen AA, Swain M, Buie M, Underwood FE, Kaplan GG. Global Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:122-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 121.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Moraes JM, Felga GE, Chebli LA, Franco MB, Gomes CA, Gaburri PD, Zanini A, Chebli JM. A full solid diet as the initial meal in mild acute pancreatitis is safe and result in a shorter length of hospitalization: results from a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:517-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Horibe M, Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Minami K, Yahagi N, Iwasaki E, Kanai T. Timing of oral refeeding in acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:725-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sathiaraj E, Murthy S, Mansard MJ, Rao GV, Mahukar S, Reddy DN. Clinical trial: oral feeding with a soft diet compared with clear liquid diet as initial meal in mild acute pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:777-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Forsmark CE, Vege SS, Wilcox CM. Acute Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1972-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dickerson RN, Vehe KL, Mullen JL, Feurer ID. Resting energy expenditure in patients with pancreatitis. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:484-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Valainathan S, Boukris A, Arapis K, Schoch N, Goujon G, Konstantinou D, Bécheur H, Pelletier AL. Energy expenditure in acute pancreatitis evaluated by the Harris-Benedict equation compared with indirect calorimetry. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2019;33:57-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Solomon SS, Duckworth WC, Jallepalli P, Bobal MA, Iyer R. The glucose intolerance of acute pancreatitis: hormonal response to arginine. Diabetes. 1980;29:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bouffard YH, Delafosse BX, Annat GJ, Viale JP, Bertrand OM, Motin JP. Energy expenditure during severe acute pancreatitis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1989;13:26-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Grinsven J, van Vugt JLA, Gharbharan A, Bollen TL, Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, van Eijck CHJ, Boerma D; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. The Association of Computed Tomography-Assessed Body Composition with Mortality in Patients with Necrotizing Pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1000-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Lakananurak N, Gramlich L. Nutrition management in acute pancreatitis: Clinical practice consideration. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:1561-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 12. | Arvanitakis M, Ockenga J, Bezmarevic M, Gianotti L, Krznarić Ž, Lobo DN, Löser C, Madl C, Meier R, Phillips M, Rasmussen HH, Van Hooft JE, Bischoff SC. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:612-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, McCarthy MS, Davanos E, Rice TW, Cresci GA, Gervasio JM, Sacks GS, Roberts PR, Compher C; Society of Critical Care Medicine; American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40:159-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1695] [Cited by in RCA: 1868] [Article Influence: 207.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Jensen GL, Cederholm T, Correia MITD, Gonzalez MC, Fukushima R, Higashiguchi T, de Baptista GA, Barazzoni R, Blaauw R, Coats AJS, Crivelli A, Evans DC, Gramlich L, Fuchs-Tarlovsky V, Keller H, Llido L, Malone A, Mogensen KM, Morley JE, Muscaritoli M, Nyulasi I, Pirlich M, Pisprasert V, de van der Schueren M, Siltharm S, Singer P, Tappenden KA, Velasco N, Waitzberg DL, Yamwong P, Yu J, Compher C, Van Gossum A. GLIM Criteria for the Diagnosis of Malnutrition: A Consensus Report From the Global Clinical Nutrition Community. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;43:32-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 60.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cederholm T, Barazzoni R, Austin P, Ballmer P, Biolo G, Bischoff SC, Compher C, Correia I, Higashiguchi T, Holst M, Jensen GL, Malone A, Muscaritoli M, Nyulasi I, Pirlich M, Rothenberg E, Schindler K, Schneider SM, de van der Schueren MA, Sieber C, Valentini L, Yu JC, Van Gossum A, Singer P. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:49-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 908] [Cited by in RCA: 1482] [Article Influence: 164.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Klein S. A primer of nutritional support for gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1677-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Petrov MS, Correia MI, Windsor JA. Nasogastric tube feeding in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. A systematic review of the literature to determine safety and tolerance. JOP. 2008;9:440-448. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Haddad SH, Al-Dorzi HM, Tamim HM, Jones G, Mehta S, McIntyre L, Solaiman O, Sakkijha MH, Sadat M, Afesh L; PermiT Trial Group. Permissive Underfeeding or Standard Enteral Feeding in Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2398-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang D, Li H, Li Y, Qu L. Gut rest strategy and trophic feeding in the acute phase of critical illness with acute gastrointestinal injury. Nutr Res Rev. 2019;32:176-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McClave SA, DiBaise JK, Mullin GE, Martindale RG. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition Therapy in the Adult Hospitalized Patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34; quiz 335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, Casaer MP, Hiesmayr M, Mayer K, Montejo JC, Pichard C, Preiser JC, van Zanten ARH, Oczkowski S, Szczeklik W, Bischoff SC. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:48-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 989] [Cited by in RCA: 1530] [Article Influence: 218.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lappas BM, Patel D, Kumpf V, Adams DW, Seidner DL. Parenteral Nutrition: Indications, Access, and Complications. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47:39-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Petrov MS, Whelan K. Comparison of complications attributable to enteral and parenteral nutrition in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1287-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wu LM, Sankaran SJ, Plank LD, Windsor JA, Petrov MS. Meta-analysis of gut barrier dysfunction in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1644-1656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Agarwal S, Goswami P, Poudel S, Gunjan D, Singh N, Yadav R, Kumar U, Pandey G, Saraya A. Acute pancreatitis is characterized by generalized intestinal barrier dysfunction in early stage. Pancreatology. 2023;23:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Al-Omran M, Albalawi ZH, Tashkandi MF, Al-Ansary LA. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition for acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010:CD002837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yao H, He C, Deng L, Liao G. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients with severe pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:66-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Petrov MS, Pylypchuk RD, Uchugina AF. A systematic review on the timing of artificial nutrition in acute pancreatitis. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:787-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Feng P, He C, Liao G, Chen Y. Early enteral nutrition versus delayed enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Stimac D, Poropat G, Hauser G, Licul V, Franjic N, Valkovic Zujic P, Milic S. Early nasojejunal tube feeding versus nil-by-mouth in acute pancreatitis: A randomized clinical trial. Pancreatology. 2016;16:523-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bakker OJ, van Brunschot S, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Bosscha K, Ahmed Ali U, Bouwense S, van Grevenstein WM, Heisterkamp J, Houdijk AP, Jansen JM, Karsten TM, Manusama ER, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Schaapherder AF, van der Schelling GP, Schwartz MP, Spanier BW, Tan A, Vecht J, Weusten BL, Witteman BJ, Akkermans LM, Bruno MJ, Dijkgraaf MG, van Ramshorst B, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Early versus on-demand nasoenteric tube feeding in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1983-1993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jin M, Zhang H, Lu B, Li Y, Wu D, Qian J, Yang H. The optimal timing of enteral nutrition and its effect on the prognosis of acute pancreatitis: A propensity score matched cohort study. Pancreatology. 2017;17:651-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Petrov MS, Loveday BP, Pylypchuk RD, McIlroy K, Phillips AR, Windsor JA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enteral nutrition formulations in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1243-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Windsor AC, Kanwar S, Li AG, Barnes E, Guthrie JA, Spark JI, Welsh F, Guillou PJ, Reynolds JV. Compared with parenteral nutrition, enteral feeding attenuates the acute phase response and improves disease severity in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1998;42:431-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Gupta R, Patel K, Calder PC, Yaqoob P, Primrose JN, Johnson CD. A randomised clinical trial to assess the effect of total enteral and total parenteral nutritional support on metabolic, inflammatory and oxidative markers in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis (APACHE II > or =6). Pancreatology. 2003;3:406-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tiengou LE, Gloro R, Pouzoulet J, Bouhier K, Read MH, Arnaud-Battandier F, Plaze JM, Blaizot X, Dao T, Piquet MA. Semi-elemental formula or polymeric formula: is there a better choice for enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Weeks C. Home Blenderized Tube Feeding: A Practical Guide for Clinical Practice. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10:e00001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hurt RT, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Epp LM, Pattinson AK, Lammert LM, Lintz JE, Mundi MS. Blenderized Tube Feeding Use in Adult Home Enteral Nutrition Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30:824-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kumar A, Singh N, Prakash S, Saraya A, Joshi YK. Early enteral nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing nasojejunal and nasogastric routes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Eatock FC, Chong P, Menezes N, Murray L, McKay CJ, Carter CR, Imrie CW. A randomized study of early nasogastric versus nasojejunal feeding in severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:432-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Singh N, Sharma B, Sharma M, Sachdev V, Bhardwaj P, Mani K, Joshi YK, Saraya A. Evaluation of early enteral feeding through nasogastric and nasojejunal tube in severe acute pancreatitis: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Pancreas. 2012;41:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Dutta AK, Goel A, Kirubakaran R, Chacko A, Tharyan P. Nasogastric versus nasojejunal tube feeding for severe acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3:CD010582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 43. | Van Dyck L, Casaer MP. Intermittent or continuous feeding: any difference during the first week? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yong L, Lu QP, Liu SH, Fan H. Efficacy of Glutamine-Enriched Nutrition Support for Patients With Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Meta-Analysis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40:83-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Jeurnink SM, Nijs MM, Prins HA, Greving JP, Siersema PD. Antioxidants as a treatment for acute pancreatitis: A meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2015;15:203-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Moggia E, Koti R, Belgaumkar AP, Fazio F, Pereira SP, Davidson BR, Gurusamy KS. Pharmacological interventions for acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | van Minnen LP, Timmerman HM, Lutgendorff F, Verheem A, Harmsen W, Konstantinov SR, Smidt H, Visser MR, Rijkers GT, Gooszen HG, Akkermans LM. Modification of intestinal flora with multispecies probiotics reduces bacterial translocation and improves clinical course in a rat model of acute pancreatitis. Surgery. 2007;141:470-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Buskens E, Boermeester MA, van Goor H, Timmerman HM, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Bollen TL, van Ramshorst B, Witteman BJ, Rosman C, Ploeg RJ, Brink MA, Schaapherder AF, Dejong CH, Wahab PJ, van Laarhoven CJ, van der Harst E, van Eijck CH, Cuesta MA, Akkermans LM, Gooszen HG; Dutch Acute Pancreatitis Study Group. Probiotic prophylaxis in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:651-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 944] [Cited by in RCA: 862] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Gou S, Yang Z, Liu T, Wu H, Wang C. Use of probiotics in the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2014;18:R57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Huang W, de la Iglesia-García D, Baston-Rey I, Calviño-Suarez C, Lariño-Noia J, Iglesias-Garcia J, Shi N, Zhang X, Cai W, Deng L, Moore D, Singh VK, Xia Q, Windsor JA, Domínguez-Muñoz JE, Sutton R. Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency Following Acute Pancreatitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:1985-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kahl S, Schütte K, Glasbrenner B, Mayerle J, Simon P, Henniges F, Sander-Struckmeier S, Lerch MM, Malfertheiner P. The effect of oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation on the course and outcome of acute pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind parallel-group study. JOP. 2014;15:165-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Reintam Blaser A, Malbrain MLNG, Regli A. Abdominal pressure and gastrointestinal function: an inseparable couple? Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2017;49:146-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |