Published online Mar 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i3.430

Peer-review started: November 26, 2022

First decision: January 3, 2023

Revised: January 15, 2023

Accepted: February 22, 2023

Article in press: February 22, 2023

Published online: March 27, 2023

Processing time: 121 Days and 7.1 Hours

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignant tumors. After resection, one of the major problems is its peritoneal dissemination and recurrence. Some free cancer cells may still exist after resection. In addition, the surgery itself may lead to the dissemination of tumor cells. Therefore, it is necessary to remove residual tumor cells. Recently, some researchers found that extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage (EIPL) plus intraperitoneal chemotherapy can improve the prognosis of patients and eradicate peritoneal free cancer for GC patients. However, few studies explored the safety and long-term outcome of EIPL after curative gastrectomy.

To evaluate the efficacy and long-term outcome of advanced GC patients treated with EIPL.

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 150 patients with advanced GC were enrolled in this study. The patients were randomly allocated to two groups. All patients received laparotomy. For the non-EIPL group, peritoneal lavage was washed using no more than 3 L of warm saline. In the EIPL group, patients received 10 L or more of saline (1 L at a time) before the closure of the abdomen. The surviving rate analysis was compared by the Kaplan-Meier method. The prognostic factors were carried out using the Cox appropriate hazard pattern.

The basic information in the EIPL group and the non-EIPL group had no significant difference. The median follow-up time was 30 mo (range: 0-45 mo). The 1- and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates were 71.0% and 26.5%, respectively. The symptoms of ileus and abdominal abscess appeared more frequently in the non-EIPL group (P < 0.05). For the OS of patients, the EIPL, Borrmann classification, tumor size, N stage, T stage and vascular invasion were significant indicators. Then multivariate analysis revealed that EIPL, tumor size, vascular invasion, N stage and T stage were independent prognostic factors. The prognosis of the EIPL group was better than the non-EIPL group (P < 0.001). The 3-year survival rate of the EIPL group (38.4%) was higher than the non-EIPL group (21.7%). For the recurrence-free survival (RFS) of patients, the risk factor of RFS included EIPL, N stage, vascular invasion, type of surgery, tumor location, Borrmann classification, and tumor size. EIPL and tumor size were independent risk factors. The RFS curve of the EIPL group was better than the non-EIPL group (P = 0.004), and the recurrence rate of the EIPL group (24.7%) was lower than the non-EIPL group (46.4%). The overall recurrence rate and peritoneum recurrence rate in the EIPL group was lower than the non-EIPL group (P < 0.05).

EIPL can reduce the possibility of perioperative complications including ileus and abdominal abscess. In addition, the overall survival curve and RFS curve were better in the EIPL group.

Core Tip: It has been found that extensive intraoperative abdominal lavage (EIPL) combined with abdominal chemotherapy can improve the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. However, few studies have explored the safety and long-term efficacy of EIPL after therapeutic gastrectomy. This randomized study evaluated the efficacy and long-term outcome of advanced gastric cancer patients with extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage.

- Citation: Song ED, Xia HB, Zhang LX, Ma J, Luo PQ, Yang LZ, Xiang BH, Zhou BC, Chen L, Sheng H, Fang Y, Han WX, Wei ZJ, Xu AM. Efficacy and outcome of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage plus surgery vs surgery alone with advanced gastric cancer patients. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(3): 430-439

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i3/430.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i3.430

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignant tumors. Its morbidity and mortality in China have been increasing in recent years[1,2]. Despite great advances in surgery and other treatment, the 5-year survival rate of GC is low[3,4]. After resection, one of the major problems is its peritoneal dissemination and recurrence. Peritoneal recurrence is more likely to occur in advanced GC patients. Although chemotherapy is applied, the prognosis of these patients remains poor[5].

Some free cancer cells may still exist after resection. In addition, the surgery itself may lead to the dissemination of tumor cells[6,7]. Therefore, it is necessary to remove residual tumor cells. Recently, extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage (EIPL) has received more attention. It is a useful treatment that can wash the abdominal cavity completely using 10 L of physiological saline (up to 10 times). Based on a previous study, EIPL is a safe and simple procedure[8]. Some researchers found that EIPL plus intraperitoneal chemotherapy can improve the prognosis of patients[9]. This technique can eradicate peritoneal free cancer, which is beneficial for the recurrence-free survival (RFS) of GC patients[7,10]. However, few studies explored the safety and long-term outcome of EIPL after curative gastrectomy.

In this study, we explored the efficacy and 3-year outcome of advanced GC patients with the technique of EIPL and analyzed the possible mechanism.

The study population was advanced GC patients with clinically T3 or T4 and M0 disease according to computed tomographic scans and ultrasonographic gastroscopy. The seventh American Joint Committee was used for the tumor, node and metastasis stage. Each patient signed the informed consent, and this study was approved by the institutional review board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Anqing Municipal Hospital and The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University.

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, patients were included in the research. The inclusion criteria included: (1) All patients were confirmed GC with T3/4NanyM0; (2) The surgery was definite and complete resection of cancer; (3) These patients did not have heart disease or any important organ failure; and (4) The patient was available for follow-up. The exclusion criteria included: (1) The patient had previous malignant tumors or various primary tumors; and (2) The patient had accepted radiation treatment or chemotherapy treatment previously.

If patients were confirmed with cT3 or cT4 and M0 disease and were suitable for radical gastrectomy, they were formally included in the study and then randomized. Patients were randomized to the EIPL group or non-EIPL group in a 1:1 ratio. Allocation was performed using sealed opaque envelopes that contained computer-generated random numbers and the procedure to which patients were allocated. Research participants were randomized to the EIPL arm or non-EIPL arm based on random permuted blocks with a varying block size of four, assuming equal allocation between treatment arms. The cytological examination was performed by introducing saline into the cavity. The cytological statuses were negative. After the exploratory operation, the envelopes were opened to determine whether EIPL was applied. A total, proximal or distal gastrectomy was completed depending on the primary tumor location. Total gastrectomy or partial resection with D2 lymphadenectomy was performed by the guidelines of the Japanese Research Society[11]. All patients received laparotomy, which reduced the influence of surgical methods. In addition, after clinical preoperative evaluation, the patient’s preoperative nutritional status was good.

For the non-EIPL group, peritoneal lavage was washed using no more than 3 L of warm saline. In the EIPL group, patients received 10 L or more of saline (1 L at a time) before the closure of the abdomen. Patients were excluded if the stage was not detected as T3 or T4 and M0. In the end, 100 patients were finally included in this study between March 2016 and March 2017. The external population included 50 GC patients who were hospitalized at The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University and Anqing Municipal Hospital from March 2016 to November 2017, and the methods and procedures were consistent with our group (Supplementary Figure 1).

The patient’s demographic and clinicopathological data were recorded, including age, sex, tumor location, tumor size, differentiation grade, pathological type, etc. The routine laboratory data including neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), etc were collected.

Peripheral blood tests were obtained within 1 wk before surgery and on the 2nd day after surgery. The cutoff value of CEA was determined according to the normal level. We determined the following indexes: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR); neutrophil count; and lymphocyte count. These two variables were grouped into the low group and high group according to the optimal cutoff values, which were calculated based on the Youden index [maximum (sensitivity + specificity-1)][12].

Tumor location was classified into five subgroups according to the anatomy of the stomach: gastric cardia; fundus of stomach; body of stomach; gastric antrum; and pylorus. Among them, upper means cardia and fundus of stomach. Middle means body of stomach. Low means gastric antrum and pylorus. To prevent the influence of esophageal cancer on the results of this study, gastroesophageal junction tumors were not included in our research. The postoperative complications, the length of hospital stay and other outcomes were also recorded. The complications included abscess, leakage, bleeding, etc.

After the operation, the patients received eight 3-wk cycles of oral S-1 plus intravenous oxaliplatin. Diagnosis of recurrence was made by abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, gastroscopy and pathology tests. We collected follow-up data through telephone and outpatient visits every 90 d until December 2020.

The baseline characteristics analysis of the non-EIPL group and EIPL group patients was performed including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, tumor location, differentiated grade, T stage, N stage, tumor size, Borrmann classification, CEA, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, NLR and platelet count. The outcome after surgery was analyzed, including type of surgery, the time from surgery to first flatus, postoperative hospital stays, abdominal pain, ileus, abdominal abscess, leakage, bleeding, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, NLR and platelet count. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and were analyzed by the Student’s t-test. Categorical values were identified by count (percent) and were analyzed by χ2test or Fisher exact test. The Kaplan-Meier method and Log-rank test were used to compare the prognosis of the non-EIPL group and EIPL group. In addition, variables including sex, age, EIPL/non-EIPL, tumor size, type of surgery, tumor location, Borrmann classification, differentiated grade, T stage, N stage and vascular invasion were enrolled into the univariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model to determine the factors influencing the GC patient’s overall survival (OS). Subsequently, risk factors screened by univariate analysis (P < 0.05) were enrolled into the multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model to determine the independent risk factors influencing the OS. The SPSS app (17.0 version) was used for statistical analysis.

The baseline characteristic analysis of the 150 patients was shown in Table 1. Among them, 109 (72.67%) were male, and 41 (27.33%) were female. The median age was 67 years (range: 35-80 years). The basic information in the EIPL group and the non-EIPL group had no significant difference. The median follow-up time was 30 mo (range: 0-45 mo). The 1- and 3-year OS rates were 71.0% and 26.5%, respectively.

| Variables | Non-EIPL group, n = 75 | EIPL group, n = 75 | P value |

| Age in yr | 66.93 ± 9.38 | 64.55 ± 8.22 | 0.099 |

| Sex | 0.200 | ||

| Male | 51 | 58 | |

| Female | 24 | 17 | |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 21.51 ± 2.29 | 21.64 ± 3.34 | 0.786 |

| Smoking status | 0.373 | ||

| Yes | 55 | 50 | |

| No | 20 | 25 | |

| Tumor location | 0.260 | ||

| Upper | 21 | 14 | |

| Middle | 11 | 17 | |

| Low | 43 | 44 | |

| Differentiated grade | 0.121 | ||

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Middle | 55 | 45 | |

| Low | 20 | 30 | |

| T stage | 0.405 | ||

| T3 | 4 | 2 | |

| T4 | 71 | 73 | |

| N stage | 0.112 | ||

| N0 | 13 | 24 | |

| N1 | 18 | 12 | |

| N2 | 14 | 17 | |

| N3 | 30 | 22 | |

| Tumor size in cm | 5.52 ± 2.21 | 5.37 ± 2.32 | 0.671 |

| Borrmann classification | 0.100 | ||

| II | 7 | 14 | |

| III | 68 | 61 | |

| CEA in g/L | 16.21 ± 78.06 | 14.13 ± 35.88 | 0.834 |

| Neutrophil count as 109/L | 3.49 ± 1.32 | 4.71 ± 8.39 | 0.215 |

| Lymphocyte count as 109/L | 1.35 ± 0.47 | 1.76 ± 2.48 | 0.164 |

| NLR | 3.02 ± 1.96 | 3.03 ± 2.20 | 0.989 |

| Platelet as 109/L | 202.52 ± 61.39 | 226.19 ± 90.94 | 0.064 |

Table 2 presented the results of surgery. There was no significant difference in time (surgery to first flatus), postoperative hospital stay, abdominal pain, bleeding, leakage or another blood index between the two groups (P > 0.05), but the symptoms of ileus and abdominal abscess appeared more frequently in the non-EIPL group (P < 0.05).

| Variables | Non-EIPL group, n = 75 | EIPL group, n = 75 | P value |

| Type of surgery | 0.242 | ||

| Total | 55 | 61 | |

| Distal | 20 | 14 | |

| Time, surgery to first flatus in d | 4.19 ± 0.99 | 3.95 ± 0.87 | 0.108 |

| Postoperative hospital stay in d | 15.26 ± 3.10 | 14.48 ± 1.97 | 0.072 |

| Abdominal pain | 10/75 | 5/75 | 0.174 |

| Ileus | 15/75 | 3/75 | 0.003 |

| Abdominal abscess | 9/75 | 1/75 | 0.009 |

| Leakage | 5/75 | 2/75 | 0.246 |

| Bleeding | 6/75 | 3/75 | 0.302 |

| Neutrophil count as 109/L | 10.36 ± 3.32 | 10.03 ± 3.56 | 0.552 |

| Lymphocyte cell as 109/L | 1.02 ± 0.63 | 1.00 ± 0.60 | 0.817 |

| NLR | 13.48 ± 8.55 | 11.87 ± 5.22 | 0.169 |

| Platelet as 109/L | 171.00 ± 59.98 | 179.73 ± 60.38 | 0.381 |

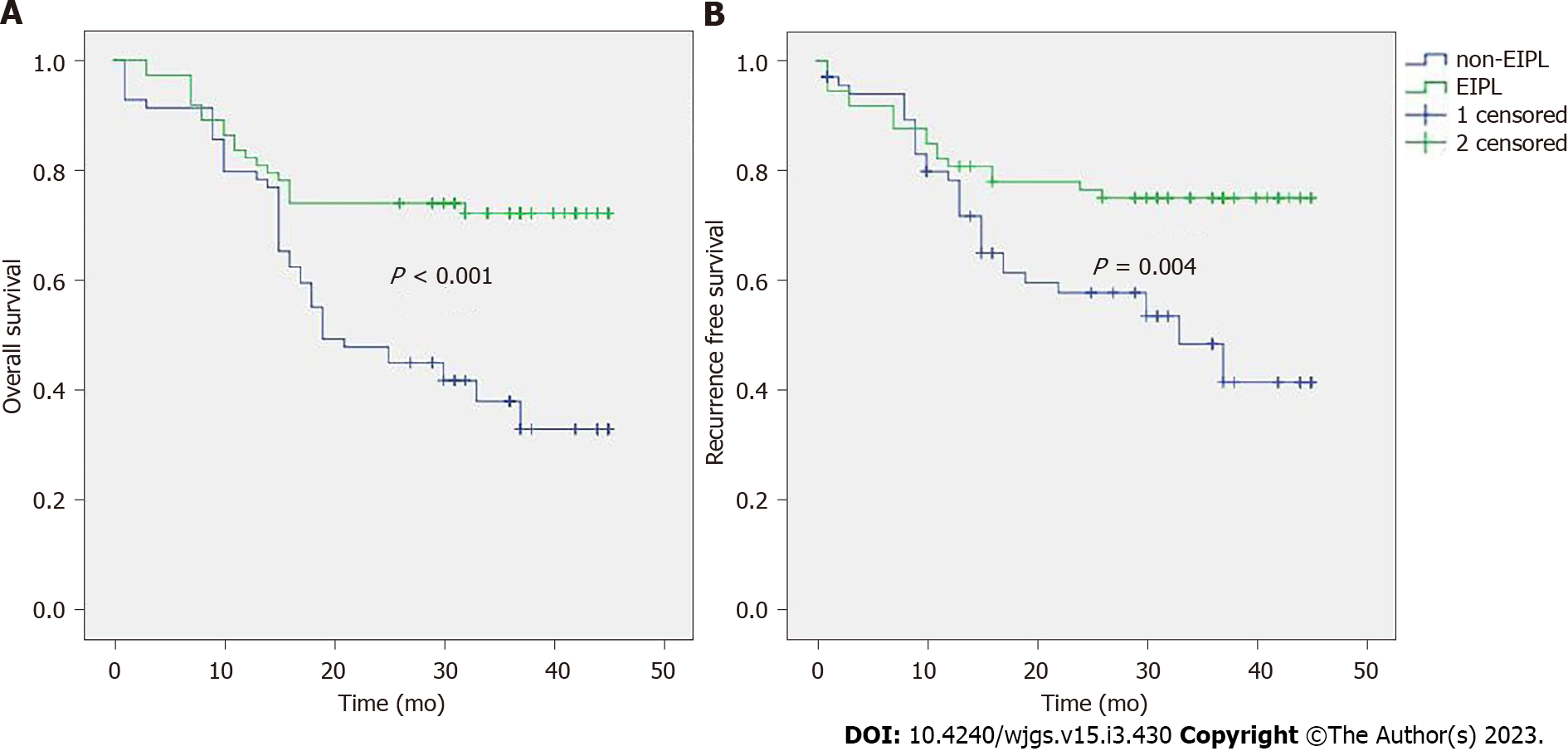

Risk factors of OS were shown in Table 3. The result showed that the EIPL, Borrmann classification, tumor size, N stage, T stage and vascular invasion were significant indicators. Then multivariate analysis revealed that EIPL, tumor size, vascular invasion, N stage and T stage were independent prognostic factors (Table 4). The survival curve (Figure 1A) revealed that the prognosis of the EIPL group was better than the non-EIPL group (P < 0.001). The 3-year survival rate of the EIPL group (38.4%) was higher than the non-EIPL group (21.7%).

| Variable | β | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Sex | 0.514 | 1.671 (0.983-2.841) | 0.058 |

| Age | 0.024 | 1.025 (0.994-1.056) | 0.114 |

| EIPL/Non-EIPL | -0.991 | 0.371 (0.218,0.631) | 0.000 |

| Tumor size | 0.192 | 1.211 (1.088-1.348) | 0.000 |

| Type of surgery | 0.185 | 1.203 (0.653-2.214) | 0.553 |

| Tumor location | 0.075 | 0.928 (0.689-1.250) | 0.622 |

| Borrmann classification | -1.474 | 0.229 (0.072-0.731) | 0.013 |

| Differentiated grade | 0.491 | 0.612 (0.351-1.067) | 0.083 |

| T stage | 1.250 | 3.489 (1.094-11.130) | 0.035 |

| N stage | 0.535 | 1.707 (1.339-2.176) | 0.000 |

| Vascular invasion | -0.954 | 0.385 (0.235-0.632) | 0.000 |

| Variable | β | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| EIPL/Non-EIPL | -0.861 | 0.423 (0.246-0.727) | 0.002 |

| Tumor size | 0.139 | 1.149 (1.025-1.289) | 0.017 |

| Borrmann classification | -0.268 | 0.765 (0.211-2.775) | 0.684 |

| T stage | 1.395 | 4.034 (1.255-12.971) | 0.019 |

| N stage | 0.313 | 1.368 (1.034-1.811) | 0.029 |

| Vascular invasion | -0.608 | 0.545 (0.317-0.935) | 0.027 |

The risk factor of RFS included EIPL, N stage, vascular invasion, type of surgery, tumor location, Borrmann classification and tumor size (Supplementary Table 1). EIPL and tumor size were independent risk factors (Supplementary Table 2). The RFS curve of the EIPL group was better than the non-EIPL group (P = 0.004) (Figure 1B), and the recurrence rate of the EIPL group (24.7%) was lower than the non-EIPL group (46.4%).

The recurrence rate of lymph node, node and other organs in the EIPL group and the non-EIPL group were not significantly different (P > 0.05), but the overall recurrence rate and peritoneum recurrence rate in the EIPL group was lower than the non-EIPL group (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 3).

Positive peritoneal lavage cytology and peritoneal recurrence are associated with the prognosis of GC[13,14]. Previous research has reported that EIPL combined with intraperitoneal treatment is an effective treatment for GC patients[9] that can reduce the recurrence rate of advanced patients. However, the safety and effect of EIPL alone remained unclear. Therefore, this study explored the clinical value of EIPL.

Our results indicated that the OS curve and RFS curve of the EIPL group were better than the non-EIPL group, and the technique of EIPL was a significant factor in OS and RFS in advanced GC patients. EIPL may reduce the recurrence rate of the tumor and improve the outcome for patients. Yamamoto et al[6] also conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of EIPL with pancreatic cancer patients and found similar conclusions. Based on these studies, the technique of EIPL needs to be applied to abdominal cancers.

Intraoperative bleeding and surgery can lead to residual tumor cells in the abdominal cavities, which may increase the risk of peritoneal metastasis. In our study, intraoperative blood loss between two groups was not significantly different. In the non-EIPL group, intraperitoneal lavage does not exceed 3 L of saline, which may make it difficult to remove free peritoneal cancer cells. The technique of EIPL can remove free cancer cells and blood in the abdominal cavity with plenty of washing (10 L or more of saline), which can prevent free cancer cells from attaching to the peritoneum[15].

In recent years, several reports[15-17] have shown that inflammation was linked to poor survival. Inflammation can stimulate the proliferation of malignant tumors cells, promote metastasis and destroy the adaptive immune response[16]. In this study, we found that the preoperative inflammatory index of NLR in the non-EIPL group was lower than in the EIPL group. However, the level of postoperative NLR in the non-EIPL group was higher than in the EIPL group. As for patients with high levels of NLR, the anti-tumor immune response of T cells and natural killer cells in the system may be surrounded by several neutrophils, which may decrease the opportunity to contact tumor cells[17,18]. Therefore, the free peritoneal cancer cells may survive in this course.

This study concluded that the symptoms of ileus appeared more in the non-EIPL group than in the EIPL group. In addition, EIPL can reduce the possibility of abdominal abscess, but the complications of bleeding and leakage have no significant difference. Indeed, EIPL is similar to the so-called limiting dilution method[19]. This technique can clean up the peritoneal effusion and reduce the risk of infection. The ten washes of regular warm saline can promote intestinal motility and functional recovery, and this may be helpful for surgeons to find the bleeding location.

All patients received laparotomy, which reduced the influence of different surgical methods. The patients also had good preoperative nutritional statuses, which made no obvious difference. As for the factors of type of surgery, when the proximal resection margin ranged from 3 to 5 cm, there was no significant difference between distal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy for the 5-year OS of GC patients[20]. We concluded that EIPL can reduce the possibility of perioperative complications including ileus and abdominal abscess, and the technique of EIPL may be beneficial for perioperative complications to make patients more comfortable after the operation. This conclusion was consistent with a previous study[8].

Although EIPL could not reduce the recurrence rate of lymph nodes, nodes and other organs, the overall recurrence rate and peritoneum recurrence rate in the EIPL group were lower than in the non-EIPL group. The OS curve and RFS curve were better in the EIPL group. Currently, only three RCTs are ongoing to explore the long-term efficacy of EIPL in advanced GC. Kuramoto et al[9] concluded that the peritoneal recurrence rate of the EIPL group was significantly lower than that of the non-EIPL (6.7% vs 45.8%, P = 0.013). There was no difference in recurrence rate for liver transfer, lymph node and other organ transfer cases between the two groups, which was similar to our study. Among 88 patients who had positive cytology, EIPL-intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IPC) greatly improved the 5-year survival of patients (44%) compared with 0% in patients with surgery alone. The prognosis of patients is poorer than in our study because the recruited patients of their study had positive cytology.

Another advantage is that IPC was not used in our study. It may remove side effects associated with chemotherapy and confound the effect of EIPL. Misawa et al[21] conducted an RCT indicating that peritoneal RFS was not significantly different between the EIPL group and the non-EIPL group. The 3-year OS rate and RFS rate were better than our study, and the reason is that the proportion of T4 (49.5%) and N3 (28.1%) was smaller than our study population (T4: 96.0%, N3: 34.7%).The value of EIPL may be related to the stage of T status and N status. The patients of our study (more cases of T4 and N3) had a higher risk of recurrence, and the reduction of recurrence rate was significant in the EIPL group. One RCT based in Singapore is still ongoing[22]. Eligible patients having cT3 or cT4 with M0 disease are also in their criteria, but our study collected more clinical information and explored the safety and efficacy of the EIPL group. Our study showed that the technique of EIPL can reduce the perioperative complications of patients.

Our study had several limitations. First, we analyzed only advanced GC patients, which is not representative of all patients. Second, the sample size was relatively small, and more cases are needed to verify our results.

In conclusion, EIPL can reduce the possibility of perioperative complications including ileus and abdominal abscess. The OS curve and RFS curve were better in the EIPL group. This technique is easy and inexpensive. Therefore, EIPL can benefit advanced GC patients and would be a promising therapeutic strategy in the future.

After resection, one of the major problems is the peritoneal dissemination and recurrence of gastric cancer (GC). It is necessary to remove residual tumor cells. Recently, a study found that extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage (EIPL) plus intraperitoneal chemotherapy can improve the prognosis of patients and eradicate peritoneal free cancer for GC patients.

The efficacy and outcome of advanced GC patients treated with EIPL has not been determined.

Evaluating the efficacy and long-term outcome of advanced GC patients treated with EIPL.

A total of 150 patients with advanced GC were enrolled in this study according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and randomly allocated to 2 groups. For the non-EIPL group, peritoneal lavage was performed using no more than 3 L of warm saline. In the EIPL group, patients received 10 L or more of saline (1 L at a time) before the closure of the abdomen. The surviving rate analysis was compared by the Kaplan-Meier method. Using the Cox appropriate hazard pattern was used to screen the prognostic factors.

The basic information in the EIPL group and the non-EIPL group had no significant differences. The symptoms of ileus and abdominal abscess appeared more frequently in the non-EIPL group. The multivariate analysis revealed that EIPL, tumor size, vascular invasion, N stage and T stage were independent prognostic factors for the overall survival of patients. The prognosis of the EIPL group was better than the non-EIPL group, and the 3-year survival rate of the EIPL group was higher than the non-EIPL group. For the recurrence-free survival (RFS) of patients, the risk factor included EIPL, N stage, vascular invasion, type of surgery, tumor location, Borrmann classification and tumor size. EIPL and tumor size were independent risk factors. The RFS curve of the EIPL group was better than the non-EIPL group (P = 0.004), and the recurrence rate of the EIPL group was lower than the non-EIPL group. The overall recurrence rate and peritoneum recurrence rate in the EIPL group was lower than the non-EIPL group.

The overall survival curve and RFS curve were better in the EIPL group. The possibility of perioperative complications, including ileus and abdominal abscess, could be reduced by EIPL.

EIPL could benefit advanced GC patients because it is inexpensive and easy and would be a promising therapeutic strategy in the future.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Çiftci AB, Turkey; Li L, New Zealand S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradi-Lakeh M, MacIntyre MF, Allen C, Hansen G, Woodbrook R, Wolfe C, Hamadeh RR, Moore A, Werdecker A, Gessner BD, Te Ao B, McMahon B, Karimkhani C, Yu C, Cooke GS, Schwebel DC, Carpenter DO, Pereira DM, Nash D, Kazi DS, De Leo D, Plass D, Ukwaja KN, Thurston GD, Yun Jin K, Simard EP, Mills E, Park EK, Catalá-López F, deVeber G, Gotay C, Khan G, Hosgood HD 3rd, Santos IS, Leasher JL, Singh J, Leigh J, Jonas JB, Sanabria J, Beardsley J, Jacobsen KH, Takahashi K, Franklin RC, Ronfani L, Montico M, Naldi L, Tonelli M, Geleijnse J, Petzold M, Shrime MG, Younis M, Yonemoto N, Breitborde N, Yip P, Pourmalek F, Lotufo PA, Esteghamati A, Hankey GJ, Ali R, Lunevicius R, Malekzadeh R, Dellavalle R, Weintraub R, Lucas R, Hay R, Rojas-Rueda D, Westerman R, Sepanlou SG, Nolte S, Patten S, Weichenthal S, Abera SF, Fereshtehnejad SM, Shiue I, Driscoll T, Vasankari T, Alsharif U, Rahimi-Movaghar V, Vlassov VV, Marcenes WS, Mekonnen W, Melaku YA, Yano Y, Artaman A, Campos I, MacLachlan J, Mueller U, Kim D, Trillini M, Eshrati B, Williams HC, Shibuya K, Dandona R, Murthy K, Cowie B, Amare AT, Antonio CA, Castañeda-Orjuela C, van Gool CH, Violante F, Oh IH, Deribe K, Soreide K, Knibbs L, Kereselidze M, Green M, Cardenas R, Roy N, Tillmann T, Li Y, Krueger H, Monasta L, Dey S, Sheikhbahaei S, Hafezi-Nejad N, Kumar GA, Sreeramareddy CT, Dandona L, Wang H, Vollset SE, Mokdad A, Salomon JA, Lozano R, Vos T, Forouzanfar M, Lopez A, Murray C, Naghavi M. The Global Burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:505-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1945] [Cited by in RCA: 2055] [Article Influence: 205.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu Y, Zhang Q, Ren C, Ding Y, Jin G, Hu Z, Xu Y, Shen H. A germline variant N375S in MET and gastric cancer susceptibility in a Chinese population. J Biomed Res. 2012;26:315-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang W, Li YF, Sun XW, Chen YB, Li W, Xu DZ, Guan XX, Huang CY, Zhan YQ, Zhou ZW. Prognosis of 980 patients with gastric cancer after surgical resection. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29:923-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang LX, Chen L, Xu AM. A Simple Model Established by Blood Markers Predicting Overall Survival After Radical Resection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spratt JS, Adcock RA, Muskovin M, Sherrill W, McKeown J. Clinical delivery system for intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1980;40:256-260. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yamamoto K, Shimada S, Hirota M, Yagi Y, Matsuda M, Baba H. EIPL (extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage) therapy significantly reduces peritoneal recurrence after pancreatectomy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1321-1328. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Shimada S, Tanaka E, Marutsuka T, Honmyo U, Tokunaga H, Yagi Y, Aoki N, Ogawa M. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage and chemotherapy for gastric cancer patients with peritoneal free cancer cells. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:168-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guo J, Xu A, Sun X, Zhao X, Xia Y, Rao H, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Chen L, Zhang T, Li G, Xu H, Xu D. Combined Surgery and Extensive Intraoperative Peritoneal Lavage vs Surgery Alone for Treatment of Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: The SEIPLUS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:610-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kuramoto M, Shimada S, Ikeshima S, Matsuo A, Yagi Y, Matsuda M, Yonemura Y, Baba H. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage as a standard prophylactic strategy for peritoneal recurrence in patients with gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250:242-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Misawa K, Mochizuki Y, Sakai M, Teramoto H, Morimoto D, Nakayama H, Tanaka N, Matsui T, Ito Y, Ito S, Tanaka K, Uemura K, Morita S, Kodera Y; Chubu Clinical Oncology Group. Randomized clinical trial of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage versus standard treatment for resectable advanced gastric cancer (CCOG 1102 trial). Br J Surg. 2019;106:1602-1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1897] [Article Influence: 135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ribeiro U Jr, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Zilberstein B, Mucerino D, Yagi OK, Bresciani CC, Jacob CE, Iryia K, Gama-Rodrigues J. Does the intraoperative peritoneal lavage cytology add prognostic information in patients with potentially curative gastric resection? J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:170-176, discussion 176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nakagawa S, Nashimoto A, Yabusaki H. Role of staging laparoscopy with peritoneal lavage cytology in the treatment of locally advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arita T, Ichikawa D, Konishi H, Komatsu S, Shiozaki A, Hiramoto H, Hamada J, Shoda K, Kawaguchi T, Hirajima S, Nagata H, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Otsuji E. Increase in peritoneal recurrence induced by intraoperative hemorrhage in gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:758-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8581] [Cited by in RCA: 8322] [Article Influence: 489.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8437] [Cited by in RCA: 8178] [Article Influence: 545.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Smyth MJ, Dunn GP, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting: the roles of immunity in suppressing tumor development and shaping tumor immunogenicity. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:1-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 578] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ruiz-Tovar J, Llavero C, Muñoz JL, Zubiaga L, Diez M. Effect of Peritoneal Lavage with Clindamycin-Gentamicin Solution on Post-Operative Pain and Analytic Acute-Phase Reactants after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2016;17:357-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jiang Y, Yang F, Ma J, Zhang N, Zhang C, Li G, Li Z. Surgical and oncological outcomes of distal gastrectomy compared to total gastrectomy for middle-third gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Lett. 2022;24:291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Misawa K, Mochizuki Y, Ohashi N, Matsui T, Nakayama H, Tsuboi K, Sakai M, Ito S, Morita S, Kodera Y. A randomized phase III trial exploring the prognostic value of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage in addition to standard treatment for resectable advanced gastric cancer: CCOG 1102 study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:101-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim G, Chen E, Tay AY, Lee JS, Phua JN, Shabbir A, So JB, Tai BC. Extensive peritoneal lavage after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer (EXPEL): study protocol of an international multicentre randomised controlled trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |