Published online Feb 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i2.294

Peer-review started: December 2, 2022

First decision: December 19, 2022

Revised: December 25, 2022

Accepted: February 8, 2023

Article in press: February 8, 2023

Published online: February 27, 2023

Processing time: 87 Days and 9.7 Hours

In recent years, mesh has become a standard repair method for parastomal hernia surgery due to its low recurrence rate and low postoperative pain. However, using mesh to repair parastomal hernias also carries potential dangers. One of these dangers is mesh erosion, a rare but serious complication following hernia surgery, particularly parastomal hernia surgery, and has attracted the attention of surgeons in recent years.

Herein, we report the case of a 67-year-old woman with mesh erosion after parastomal hernia surgery. The patient, who underwent parastomal hernia repair surgery 3 years prior, presented to the surgery clinic with a complaint of chronic abdominal pain upon resuming defecation through the anus. Three months later, a portion of the mesh was excreted from the patient’s anus and was removed by a doctor. Imaging revealed that the patient’s colon had formed a t-branch tube structure, which was formed by the mesh erosion. The surgery reconstructed the structure of the colon and eliminated potential bowel perforation.

Surgeons should consider mesh erosion since it has an insidious development and is difficult to diagnose at the early stage.

Core Tip: In recent years, mesh has become a standard repair method for parastomal hernia surgery because it has the advantages of a low recurrence rate and low postoperative pain. However, using mesh to repair parastomal hernias also carries potential dangers. We report a case of a rare complication caused by mesh erosion 3 years after parastomal hernia repair using the keyhole method. Its atypical symptoms and imaging findings complicated the diagnosis. The aim of this case report was to raise awareness of this rare complication among surgeons.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Lin H, Liu JM, Wang X, Cui YF, Lu ZY. Mesh erosion into the colon following repair of parastomal hernia: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(2): 294-302

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i2/294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i2.294

Although the incidence of parastomal hernias remains unknown, it is predicted to be > 30% at 1 year, > 40% at 2 years, and ≥ 50% after many years thereafter[1]. Suture repair is undoubtedly the simplest method for parastomal hernia repair, but its recurrence rate has been reported to be higher than that of mesh repair[2]. Hence, mesh repair remains the mainstream method for treating parastomal hernias. Mesh repair can reduce the recurrence rate but may cause potential mesh-related complications. Currently, there is a lack of comparative evidence between the different mesh types for parastomal hernia repair. However, synthetic uncoated mesh types are generally not considered for intraperitoneal use because of the risk of adhesion, intestinal erosion, and stenosis[1].

Here, we present the case of a patient who underwent parastomal hernia repair with intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair mesh and developed a rare complication 3 years after the procedure. We reviewed 137 cases in 132 case reports of mesh erosion from 1973 to 2022 by searching the keywords, “Mesh Erosion” and “Mesh migration” in PubMed.

In January 2021, a 67-year-old female who had undergone parastomal hernia repair surgery 3 years prior began experiencing chronic abdominal pain upon resuming defecation through the anus.

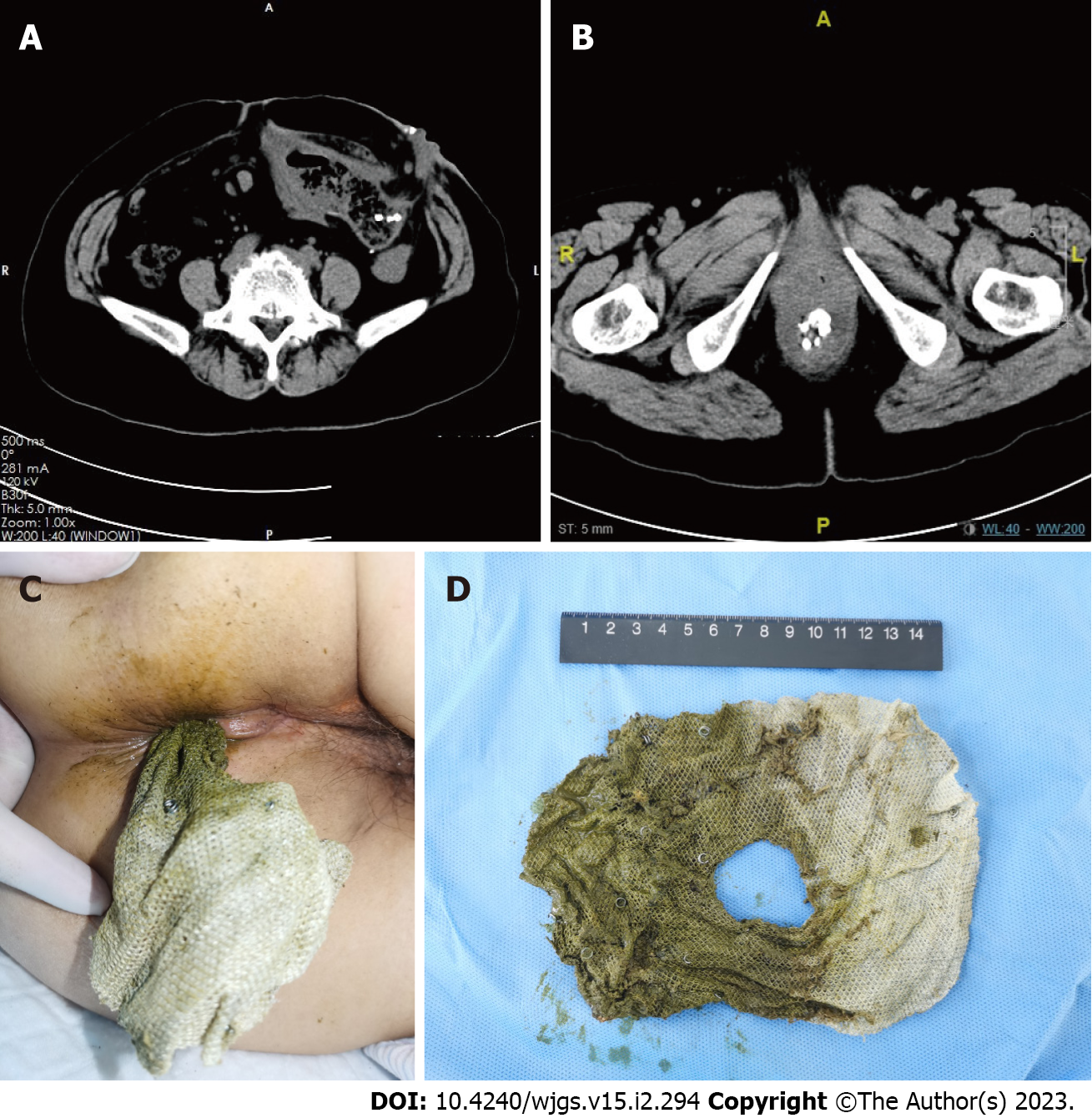

In January 2021, she underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT) for initial workup, which revealed a foreign material located in the distal colon (Figure 1A). Three months later, in April 2021, a portion of the foreign material was excreted from the patient’s anus. The patient consulted our center in an emergency and underwent CT examination again (Figure 1B). The foreign material was removed by a doctor who confirmed the foreign material as the mesh used in a parastomal hernia (Figure 1C and D).

The patient underwent anus-preserving radical resection (Dixon operation) for rectal cancer in November 2010. The pathological diagnosis revealed rectal villous tubular adenocarcinoma with negative margins and no lymph node metastasis. Four months later, she was admitted to the hospital because of difficulty with defecation and was diagnosed with postoperative anastomotic stenosis. The stenosis was removed using a colonoscope. Recurrent defecation difficulties for 3 years led to an emergency colostomy for intestinal obstruction. According to the surgical records, the distal colon was removed and closed from the peritoneal reflection. In January 2018, the patient was admitted to our center and underwent parastomal hernia mesh repair (keyhole, Shanshi, China) for an emerging parastomal hernia.

The patient underwent anus-preserving radical resection (Dixon operation) for rectal cancer in November 2010.

A portion of the foreign material was excreted from the patient’s anus. The foreign material was removed by a doctor who confirmed the foreign material as the mesh used in a parastomal hernia.

Laboratory tests were unremarkable.

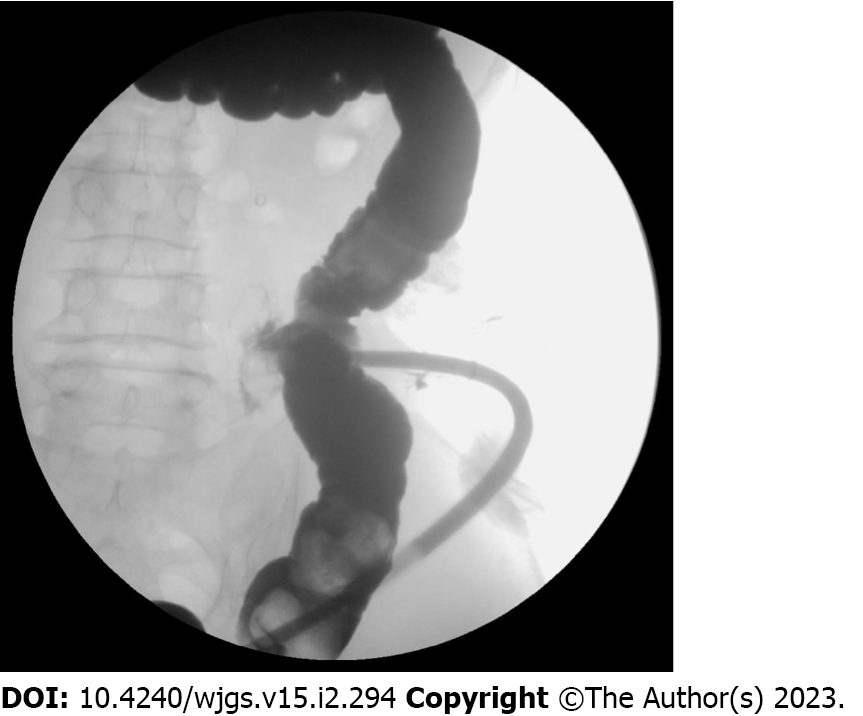

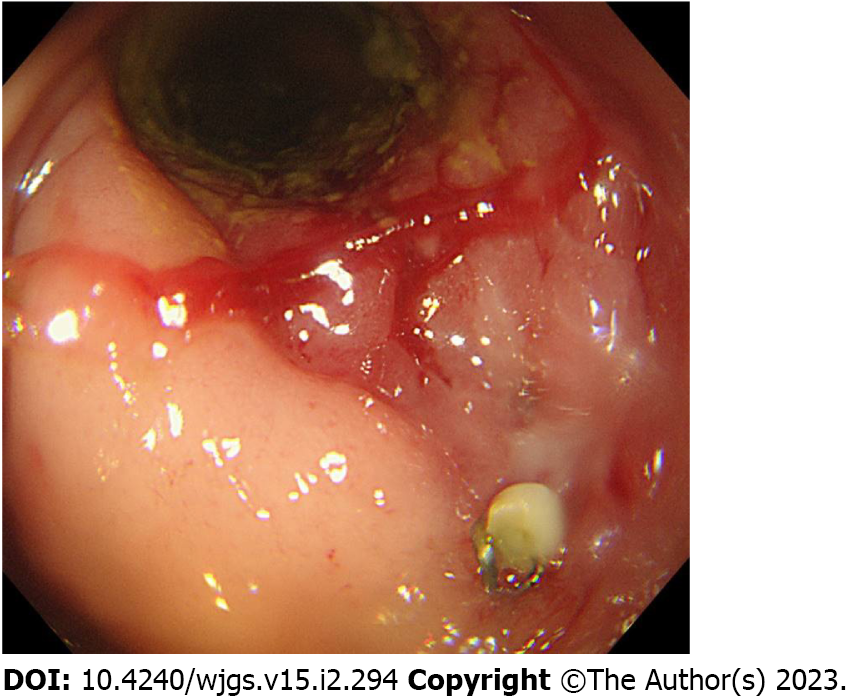

We performed gastrointestinal contrast, where a contrast agent was injected through the stoma revealing a t-branch tube structure in the enterocoelia (Figure 2). Transanal colonoscopy was performed and revealed stenosis blocking the passage of the colonoscope. Severe inflammation triggered by the mesh of the parastomal hernia was observed. Due to severe stenosis at the anastomosis, the t-branch tube structure could not be seen in this direction (Figure 3).

Mesh erosion into the colon secondary to bowel perforation.

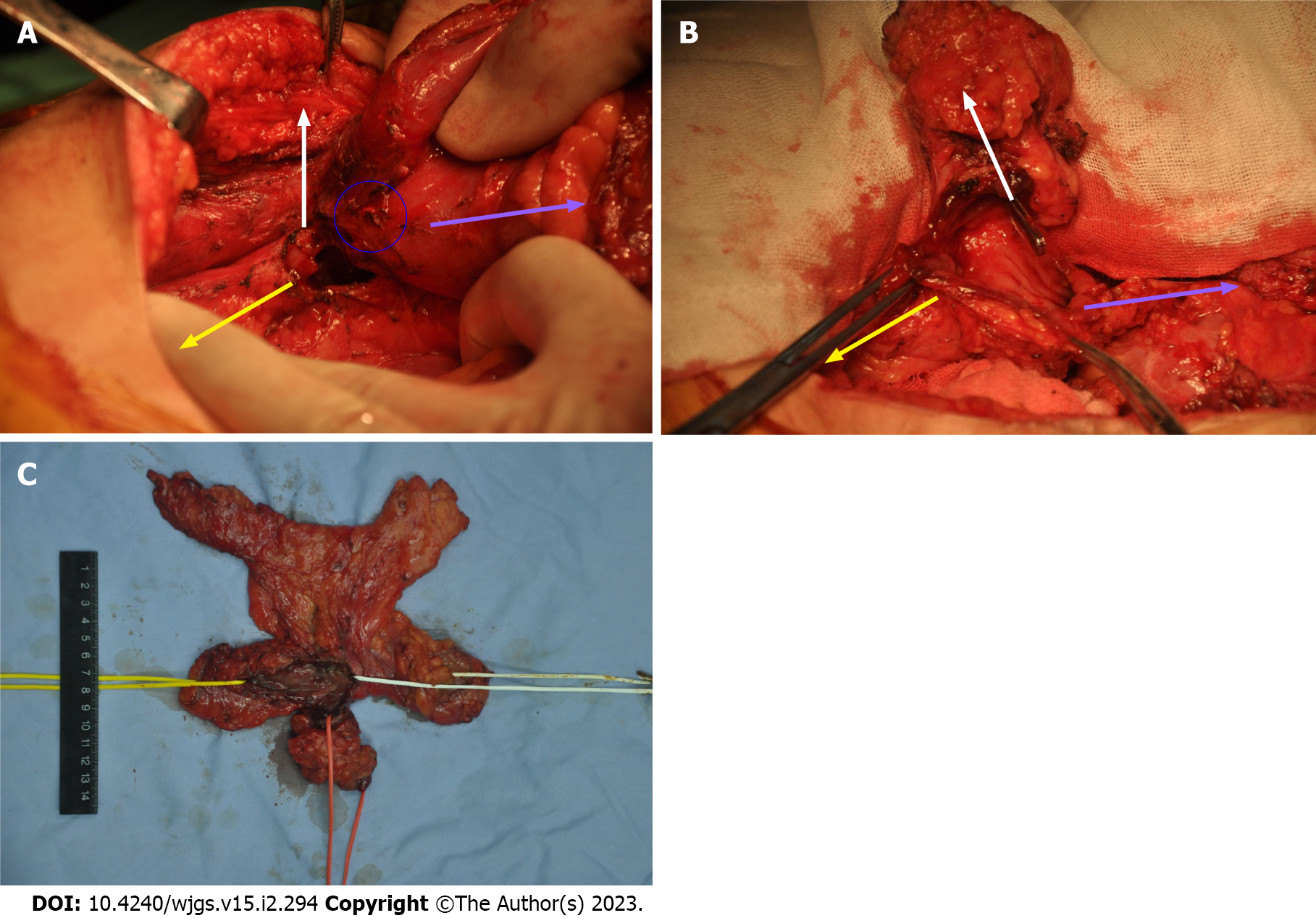

The patient was considered to have a potential intraperitoneal enteral leakage and consented to the elective operation. Midline abdominal incision was created, and the t-branch tube structure formed from the colon near the stoma, proximal and distal colons, and the lateral wall of the small intestine (Figure 4). The t-branch tube and unduly long colon was excised, and the original stoma was closed. A colostomy was reconstructed on the right side of the abdominal wall.

Pathological examination revealed granulomatous inflammation without tumor recurrence. The patient was discharged 10 d after the surgery. The patient showed no discomfort after discharge and continued receiving follow-up care on an outpatient basis.

According to the European Hernia Society guidelines on the prevention and treatment of parastomal hernias, the incidence of parastomal hernia is more than 30% 1 year after fistulization, more than 40% after 2 years, and can reach 50% or even higher over time[1]. In China, the number of patients undergoing abdominal surgery has increased, and the number of patients with parastomal hernias has gradually increased[2]. Due to the higher risk of recurrence after suture repair, mesh repair is still the best way to repair a parastomal hernia[1]. Common complications of a parastomal hernia repair include seroma, intestinal injury, intraoperative and postoperative bleeding, bowel perforation, hernia recurrence, intestinal obstruction, mesh contamination or infection, and chronic pain.

Mesh erosion is commonly considered a rare complication[3]. According to Jeans et al[4], the incidence of mesh erosion after inguinal hernia repair is less than 1%[4]. However, Hamouda et al[5] suggested that this percentage is significantly underestimated[5,6]. Targarona et al[7] reported that the incidence of graft erosion after hiatal hernia surgery was approximately 2.3%[7]. Unlike hiatal hernia, diaphragm movement is the primary cause of mesh migration and erosion[8]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the incidence of mesh erosion after parastomal hernia surgery would be lower than that after hiatal hernia surgery.

In our literature review, there was only one report of mesh erosion after parastomal hernia surgery[9]. There were only a few cases of parastomal hernia and a low incidence of mesh erosion occurring after various hernia surgeries. Particularly, mesh erosions after parastomal hernia surgeries are even more scarce. In addition, the initial symptoms are usually hematochezia, intestinal obstruction, or other digestive system symptoms. Therefore, patients often seek treatment from gastroenterology or gastrointestinal surgery causing underreporting of mesh erosion. Moreover, the primary disease leading to a stoma can shorten the lifespan of patients, which may explain why parastomal hernias are uncommon.

We used “Mesh Erosion” and “Mesh migration” as the keywords to search in PubMed. The reference lists from the extracted studies were manually reviewed to identify additional potentially eligible studies. A total of 132 reports describing 137 cases of mesh erosion from 1973 to 2022 were reviewed (Table 1). All abdominal hernia types except hiatal hernia were included. Erosion caused by mesh placement due to pelvic floor prolapse and other diseases was excluded. The selected studies included 96 cases of mesh erosion of digestive organs, 42 cases of urinary system erosion (including 8 cases of both digestive system and urinary system erosion), and 7 cases of other systems (including 1 case of the inguinal region, 1 case of the testis, 3 cases of migration of only non-eroded organs, 1 case of a uterine adnexa, and 1 case of the heart).

| Patient information | Number of cases | |

| Sex | Male | 110 |

| Female | 27 | |

| Age | ≤ 60 years old | 57 |

| > 60 years old | 80 | |

| Mesh erosion time | ≤ 6 mo | 22 |

| > 6 mo | 114 | |

| Type of hernia | Inguinal hernia | 83 |

| Incision hernia | 33 | |

| Umbilical hernia | 10 | |

| Parastomal hernia | 1 | |

| Obturator hernia | 1 | |

| Abdominal wall strengthening | 5 | |

| Abdominal wall hernia not specified | 5 | |

| History of abdominal surgery other than hernia repair | 56 | |

| Symptoms of prior mesh infection | 17 | |

| Condition of hernia after mesh erosion | Hernia recurrence | 17 |

| Incisional hernia | 3 | |

| History of chemotherapy and immune-suppressive therapy | 8 | |

Agrawal and Avill[10] believed that there are two main methods of mesh migration[10]. The first is the mesh migration along the path of least resistance caused by inadequate fixation or external forces. The second is the slow and gradual migration across the anatomical plane. The mesh may be displaced initially and then eroded into adjacent tissues, which is the erosion and migration of the mesh caused by a foreign body reaction[10]. Local tissue destruction from the inflammatory response, granulation tissue proliferation, and repetition of these two processes results in mesh erosion of the intestine. This process can take several years to occur.

Pathology and colonoscopy in the case reports of Millas et al[11], Celik et al[12], and Riaz et al[13] confirmed granulomatous inflammation at the lesion site, which proves the existence of this process and is consistent with the present case. According to Losanoff et al[14] and Hamouda et al[5], mesh erosion after inguinal hernia surgery is caused by direct contact between the rough mesh surface and organs such as the intestine. The parastomal hernia mesh includes a polyvinylidene difluoride and polyester layer and biological mesh. It is a basic requirement for a parastomal hernia mesh to contact the intestine; therefore, the effect of mesh material on intestinal erosion is irrelevant.

Riaz et al[13] suggested that trimming the sharpened edges of the mesh could prevent damage to the surface of the organs and prevent an inflammatory response that could lead to weakness and mesh erosion[13]. We agree with their opinion that an appropriate mesh should be selected to reduce the necessary trimming. Particularly in cases of parastomal hernia, the central pore should be trimmed to minimize mechanical damage caused by friction between the mesh and intestine.

Goswami et al[15] reported a case of cecal erosion after transabdominal preperitoneal for a right inguinal hernia in a patient with a history of appendectomy before transabdominal preperitoneal[15]. Goswami et al[15] indicated that the adhesion caused by the patient’s previous appendectomy predisposed the patient to further adhesion between the mesh and organ, which eventually promoted mesh erosion. Abdominal adhesions caused by previous surgeries cause the intestine to lose its ability to avoid injury. Moreover, repeated friction between the fixed intestine and the foreign body causes local tissue damage, leading to mesh erosion. Patients with parastomal hernias have had at least one or several previous operations. For a parastomal hernia, more attention should be paid to adhesions caused by previous operations on mesh erosion.

According to Yang[16], titanium tackers used to fix mesh are more likely to adhere to the intestine, which Hollinsky et al[17] confirmed through animal experiments. In our experience, titanium tackers also cause serious adhesions. Persistent inflammation may increase the risk of postoperative hernia mesh erosion and migration[11]. Parastomal hernias involve stomas; therefore, the surgical field is not as sterile as other hernia procedures, potentially leading to mesh erosion. Benedett et al[18] recommended that chemotherapy could lead to intestinal perforation and a difficult postoperative period[18]. Patients with parastomal hernia commonly have intestinal tumors, and the state of immunological prostration induced by chemotherapy should not be disregarded.

In our case, another cause that should not be overlooked is the potential iatrogenic causes. The surgeon who performed the stoma may have intended to perform secondary intestinal anastomosis; therefore, the distal colon of the closed loop was over reserved. Preoperative examination before the parastomal hernia repair did not reveal the status of a closed loop intestine. Irregular operation and incomplete preliminary examination before parastomal hernia repair are also important reasons for t-branch tube formation.

It is difficult to diagnose mesh erosion because of the level of damage needed for a patient to feel symptoms, which can vary and take many years to develop. In our review, we observed 96 bowel mesh erosion cases (Table 2). The symptoms of mesh erosion include chronic abdominal pain, vomiting, digestive tract hemorrhage, bowel perforation, and intestinal obstruction. In patients who may have one or more of these symptoms, a negative fecal occult blood test may occur[12]. Determining mesh status using radiography is also difficult[19]. Among the 96 cases reviewed, the diagnosis was established during surgery in 74 cases, on the first endoscopy in 10 cases, on at least the second endoscopy in 7 cases, and by other means such as CT in 7 cases. A convenient and inexpensive objective assessment of mesh behavior after mesh placement is difficult because there are no routinely available mesh products with unique radiographic labels[20].

| Examinations | Number of cases | ||

| First radiographic diagnosis | Positive | Mesh erosion | 0 |

| Negative | Foreign body | 1 | |

| Other lesions | 13 | ||

| No abnormal | 3 | ||

| First CT diagnosis | Positive | Mesh erosion | 4 |

| Negative | Mesh migration | 2 | |

| Foreign body | 4 | ||

| Other lesions | 44 | ||

| No abnormal | 6 | ||

| First gastrointestinal angiography diagnosis | Positive | Mesh erosion | 1 |

| Negative | Foreign body | 0 | |

| bowel perforation | 12 | ||

| Other lesions | 8 | ||

| No abnormal | 1 | ||

| First colonoscopy diagnosis | Positive | Mesh erosion | 11 |

| Negative | Foreign body | 3 | |

| Other lesions | 17 | ||

| No abnormal | 6 | ||

| Ultrasonic diagnosis | Positive | Mesh erosion | 0 |

| Negative | Mesh migration | 1 | |

| Foreign body | 1 | ||

| Other lesions | 4 | ||

| No abnormal | 2 | ||

| MRI | Positive | Mesh erosion | 0 |

| Negative | Foreign body | 0 | |

| Other lesions | 2 | ||

| No abnormal | 0 | ||

Our literature review concluded that radiography, CT, and gastrointestinal angiography could only diagnose intestinal obstruction and leakage, although identifying the actual cause was still difficult. Doppler ultrasound is only performed after clinical judgment of a doctor to determine the mesh location. In our case, because the metal tackers moved into the intestine with the mesh, the CT scan alone could diagnose mesh erosion in the intestine. Early colonoscopy can only detect inflammation, intestinal polyps, or diverticulum; therefore, it may be wrongly interpreted and misdiagnosed as a malignant tumor[21-23]. The actual cause can only be determined when patients undergo more than one colonoscopy or abdominal exploration after experiencing severe symptoms. The early diagnosis of mesh erosion is complex, and the history of hernia repair should not be ignored when a patient presents with abdominal symptoms.

In our literature review, only 9 patients did not receive surgical treatment, and the remaining patients with mesh erosions received surgical treatment. In the 9 cases opting for non-surgical treatment, some authors believed that surgery should still be performed[24-26]. Previous studies discussed that patients usually refuse surgical treatment at the onset of their symptoms but finally receive surgical treatment once they worsen[27,28]. Therefore, mesh erosion after parastomal hernia surgery should be actively treated. Due to the small number of cases, it was inconclusive if the mesh of a parastomal hernia erosion or the bowel loops should be removed and the stoma rebuilt. We believe that mesh erosion, especially penetration into the intestine, necessitates the removal of some or all of the mesh into the intestinal loops. The segment of the intestinal loop should be resected, and the stoma rebuilt. Owing to repeated operations at the original stoma, local skin scars cause difficulties in care of the stoma. Re-stoma reduces the possibility of postoperative intestinal leakage and improves the future nursing of patients.

Mesh erosion is a rare complication, but its real incidence may be higher than the reported incidence. Previous studies have speculated on the etiology, many of which are more prominent in patients with parastomal hernia after surgery. Mesh erosion has no typical clinical manifestations, imaging, and endoscopy characteristics. With its insidious behavior, mesh erosion is difficult to diagnose at an early stage. Surgeons should be aware of the surgical history of hernia repair especially when the patient with mesh presents with abdominal symptoms.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bloemendaal ALA, United Kingdom; Paparoupa M, Germany S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li L

| 1. | Antoniou SA, Agresta F, Garcia Alamino JM, Berger D, Berrevoet F, Brandsma HT, Bury K, Conze J, Cuccurullo D, Dietz UA, Fortelny RH, Frei-Lanter C, Hansson B, Helgstrand F, Hotouras A, Jänes A, Kroese LF, Lambrecht JR, Kyle-Leinhase I, López-Cano M, Maggiori L, Mandalà V, Miserez M, Montgomery A, Morales-Conde S, Prudhomme M, Rautio T, Smart N, Śmietański M, Szczepkowski M, Stabilini C, Muysoms FE. European Hernia Society guidelines on prevention and treatment of parastomal hernias. Hernia. 2018;22:183-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hansson BM, Slater NJ, van der Velden AS, Groenewoud HM, Buyne OR, de Hingh IH, Bleichrodt RP. Surgical techniques for parastomal hernia repair: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Surg. 2012;255:685-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cunningham HB, Kukreja S, Huerta S. Mesh migration into an inguinal hernia sac following a laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair. Hernia. 2018;22:715-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jeans S, Williams GL, Stephenson BM. Migration after open mesh plug inguinal hernioplasty: a review of the literature. Am Surg. 2007;73:207-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hamouda A, Kennedy J, Grant N, Nigam A, Karanjia N. Mesh erosion into the urinary bladder following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair; is this the tip of the iceberg? Hernia. 2010;14:317-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cunningham HB, Weis JJ, Taveras LR, Huerta S. Mesh migration following abdominal hernia repair: a comprehensive review. Hernia. 2019;23:235-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Targarona EM, Bendahan G, Balague C, Garriga J, Trias M. Mesh in the hiatus: a controversial issue. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1286-96; discussion 1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Griffith PS, Valenti V, Qurashi K, Martinez-Isla A. Rejection of goretex mesh used in prosthetic cruroplasty: a case series. Int J Surg. 2008;6:106-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aldridge AJ, Simson JN. Erosion and perforation of colon by synthetic mesh in a recurrent paracolostomy hernia. Hernia. 2001;5:110-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Agrawal A, Avill R. Mesh migration following repair of inguinal hernia: a case report and review of literature. Hernia. 2006;10:79-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Millas SG, Mesar T, Patel RJ. Chronic abdominal pain after ventral hernia due to mesh migration and erosion into the sigmoid colon from a distant site: a case report and review of literature. Hernia. 2015;19:849-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Celik A, Kutun S, Kockar C, Mengi N, Ulucanlar H, Cetin A. Colonoscopic removal of inguinal hernia mesh: report of a case and literature review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15:408-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Riaz AA, Ismail M, Barsam A, Bunce CJ. Mesh erosion into the bladder: a late complication of incisional hernia repair. A case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2004;8:158-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Losanoff JE, Salwen WA, Basson MD, Levi E. Large neomucosal space 25 years after mesh repair of ventral hernia. Am J Surg. 2010;199:e39-e41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Goswami R, Babor M, Ojo A. Mesh erosion into caecum following laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia (TAPP): a case report and literature review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:669-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang GPC. From intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair to preperitoneal onlay mesh repair. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;10:119-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hollinsky C, Kolbe T, Walter I, Joachim A, Sandberg S, Koch T, Rülicke T, Tuchmann A. Tensile strength and adhesion formation of mesh fixation systems used in laparoscopic incisional hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1318-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Benedetti M, Albertario S, Niebel T, Bianchi C, Tinozzi FP, Moglia P, Arcidiaco M, Tinozzi S. Intestinal perforation as a long-term complication of plug and mesh inguinal hernioplasty: case report. Hernia. 2005;9:93-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chernyak V, Rozenblit AM, Patlas M, Kaul B, Milikow D, Ricci Z. Pelvic pseudolesions after inguinal hernioplasty using prosthetic mesh: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:724-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Downey DM, DuBose JJ, Ritter TA, Dolan JP. Validation of a radiographic model for the assessment of mesh migration. J Surg Res. 2011;166:109-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Whitehead-Clarke TI, Smew F, Zaidi A, Pissas D. A mesh masquerading as malignancy: a cancer misdiagnosed. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu S, Zhou XX, Li L, Yu MS, Zhang H, Zhong WX, Ji F. Mesh migration into the sigmoid colon after inguinal hernia repair presenting as a colonic polyp: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6:564-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Chan RH, Lee KT, Wu CH, Lin WT, Lee JC. Mesh migration into the sigmoid colon mimics a colon tumor, a rare complication after herniorrhaphy: case report. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:155-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gandhi D, Marcin S, Xin Z, Asha B, Kaswala D, Zamir B. Chronic abdominal pain secondary to mesh erosion into cecum following incisional hernia repair: a case report and literature review. Ann Gastroenterol. 2011;24:321-324. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Nikhil K, Rishi N, Rajeev S. Bladder erosion and stone as rare late complication of laparoscopic hernia meshplasty: is endoscopic management an option? Indian J Surg. 2013;75:232-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mendez-Ishizaki Y, Parra JL. Obscure Overt Gastrointestinal Bleeding Secondary to Ventral Hernioplasty Mesh Small Bowel Perforation Visualized With Video Capsule Endoscopy. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3:e167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tung KLM, Cheung HYS, Tang CN. Non-healing enterocutaneous fistula caused by mesh migration. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E73-E74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | AlShammari A, Alyousef F, Alyousif A, Alsulabi Z, AlJishi F, Siraj I, Alotaibi H, Aburahmah M. Chronic abdominal pain after laparoscopic hernia repair due to mesh graft migration to the cecum: a case report. Patient Saf Surg. 2019;13:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |