Published online Dec 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i12.2945

Peer-review started: September 11, 2023

First decision: November 9, 2023

Revised: November 10, 2023

Accepted: December 2, 2023

Article in press: December 2, 2023

Published online: December 27, 2023

Processing time: 107 Days and 3.7 Hours

Groove pancreatitis (GP) is a rare condition affecting the pancreatic groove region within the dorsal-cranial part of the pancreatic head, duodenum, and common bile duct. As a rare form of chronic pancreatitis, GP poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for clinicians. GP is frequently misdiagnosed or not considered; thus, the diagnosis is often delayed by weeks or months. The treatment of GP is complicated and often requires surgical intervention, especially pancreatoduodenectomy.

A 66-year-old man with a history of long-term drinking was admitted to the gastroenterology department of our hospital, complaining of vomiting and acid reflux. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed luminal stenosis in the desce

GP often involves the descending and horizontal parts of the duodenum and causes duodenal stenosis, impaired duodenal motility, and gastric emptying due to fibrosis.

Core Tip: Groove pancreatitis (GP) is an uncommon form of chronic pancreatitis affecting the pancreatic groove region. In this case study, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed duodenal stenosis and abdominal computed tomography showed probable local pancreatitis. The symptoms of intestinal obstruction were not relieved with conservative therapy. Exploratory laparoscopy revealed a hard mass with scarring in the horizontal part of the duodenum and stenosis. Duodenojejunostomy was performed and routine pathologic examination of the mass biopsy showed extensive proliferation of fibrous tissue, indicating GP. Despite surgical therapy, the patient presented with anastomotic obstruction postoperatively and took a long time to recover.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Cheng HH, Fan WJ. Duodenojejunostomy treatment of groove pancreatitis-induced stenosis and obstruction of the horizontal duodenum: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(12): 2945-2953

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i12/2945.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i12.2945

Groove pancreatitis (GP) is an uncommon form of segmental chronic pancreatitis affecting the pancreaticoduodenal groove, which is a theoretic space bordered by the pancreatic head, duodenum, and common bile duct[1]. GP was first described by Potet and Duclert in 1970 as cystic dystrophy of the pancreas[2]. Despite increased studies in the literature, its true incidence is unknown. GP is frequently misdiagnosed or not considered, and largely remains an unfamiliar entity to most physicians. It can be treated by a conservative approach; but, depending on severity of the clinical symptoms and in cases where malignancy needs to be ruled out, a surgical intervention may be required. Pancreatoduodenectomy is the most common type of resection[3].

Here, we present a patient with duodenal obstruction caused by GP, who was difficult to diagnose. He was treated with duodenojejunostomy and had a slow recovery after surgery.

A 66-year-old man presented to the gastroenterology department of our hospital to address a 3-d history of vomiting and acid reflux.

The patient began experiencing dark vomit 3 d prior after eating soup, with acid reflux and belching. He did not have obvious abdominal pain or diarrhea.

The patient had a history of coronary heart disease for 8 years that was treated with oral clopidogrel bisulfate, rosuvastatin calcium, and bisoprolol fumarate. Three months ago, he was diagnosed with renal insufficiency and took calcium dobesilate. He also previously had surgery for varicosis of the great saphenous vein.

The patient had a 40-year history of drinking and smoking. He denied any allergy history and had an unremarkable family history.

The patient’s temperature was 36.2°C, heart rate was 136 beats per min, respiratory rate was 20 breaths per min, and blood pressure was 119/58 mmHg. Abdominal examination showed slight abdominal tenderness in the epigastric abdomen without rebound tenderness. Abdominal auscultation showed slightly hyperactive bowel sounds. Lung examination was normal.

Routine blood tests revealed an elevated white blood cell count (10.79 × 109 cells/L; normal range: 3.5-9.5 × 109 cells/L) and predominance of neutrophils (80.7%) as well as elevated levels of amylase (85 U/L; normal range: 13-53 U/L), serum urea (16.1 mmol/L; normal range: 3.6-9.5 mmol/L), creatinine (199 µmol/L; normal range: 59-104 µmol/L), and uric acid (771 µmol/L; normal range: 202.3-416.5 µmol/L). Fecal occult blood test was negative. Transaminase and lipase levels and coagulation function were normal. Tumor markers including carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigens 19-9 and 72-4 were normal. Serum gastrin levels and heavy metal blood test were normal.

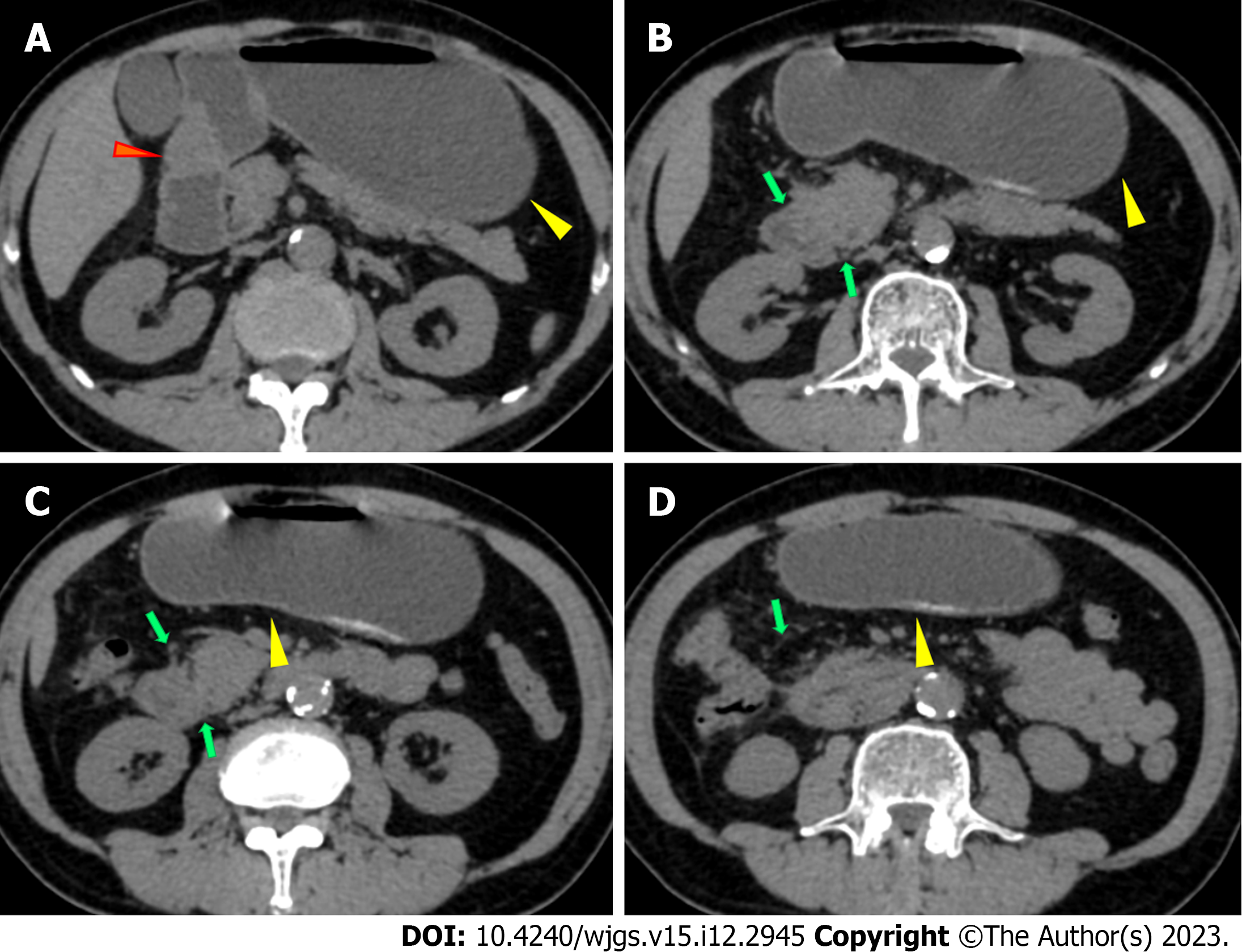

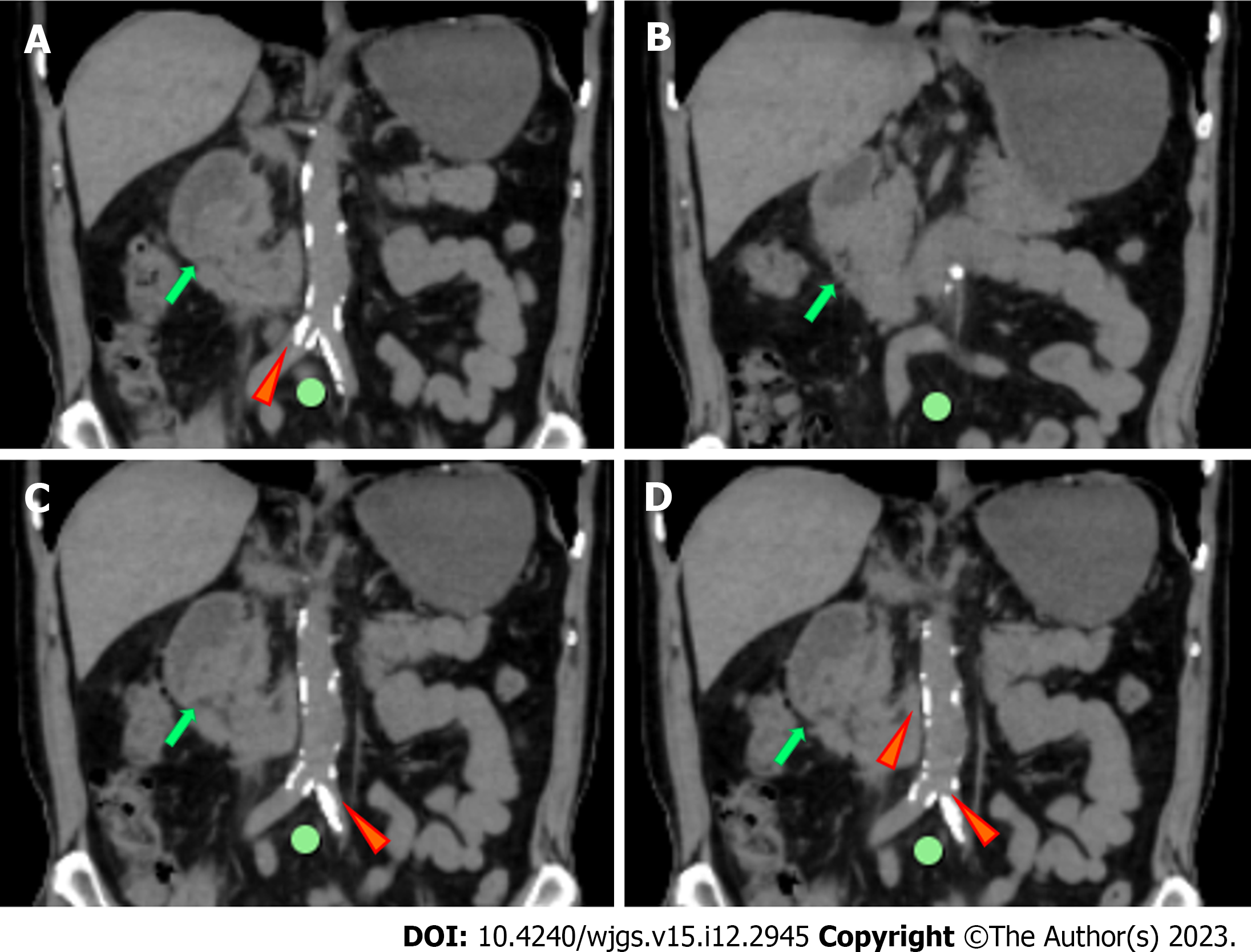

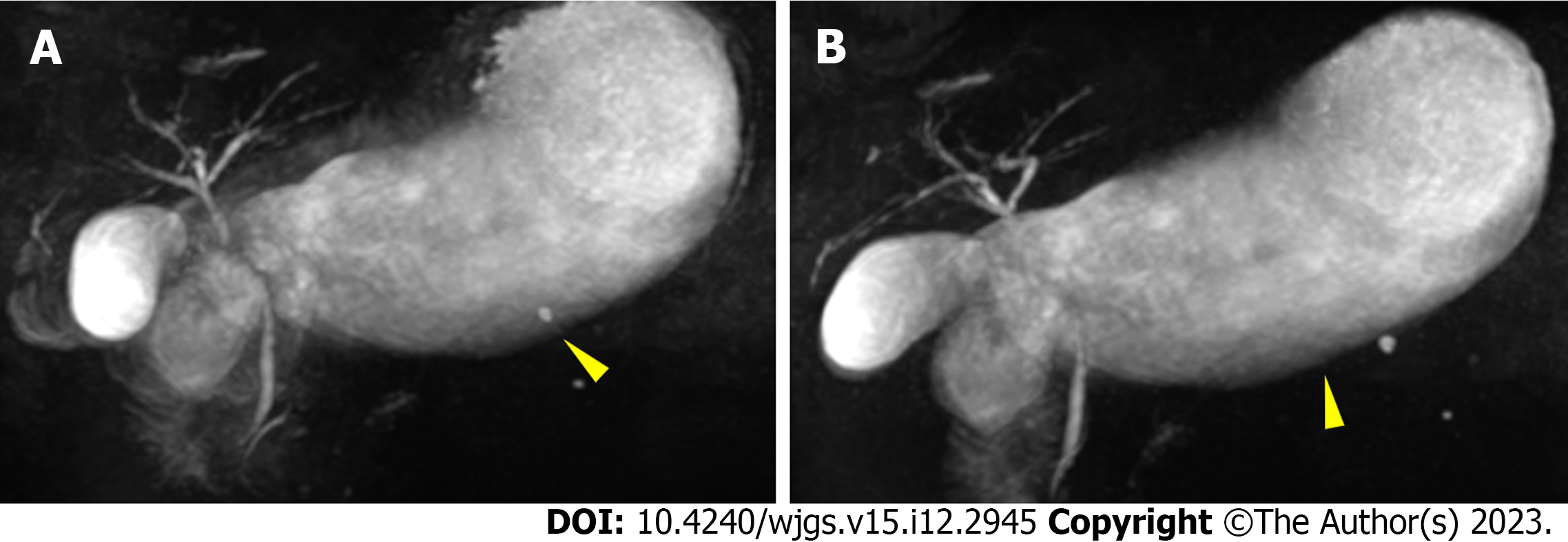

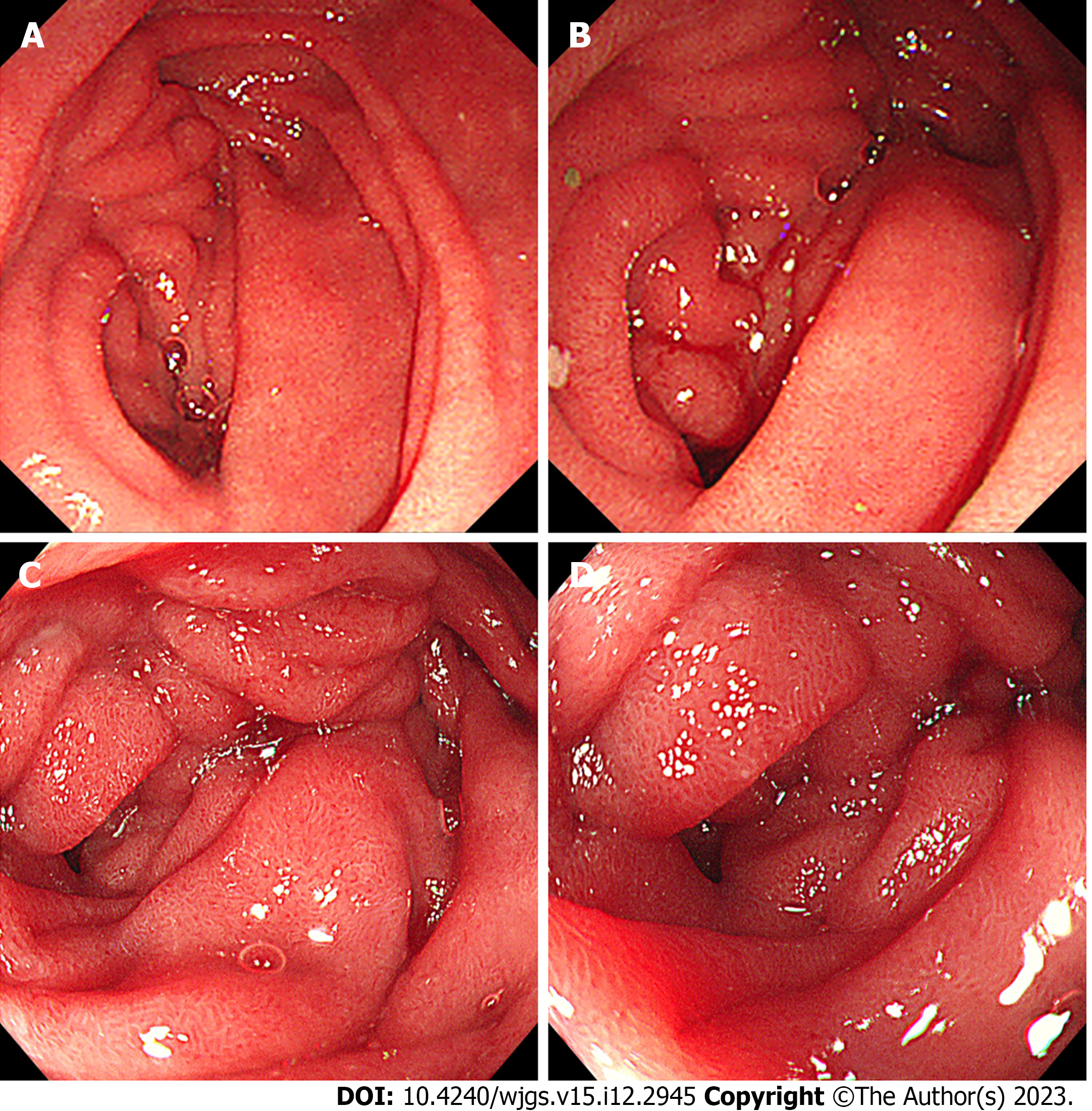

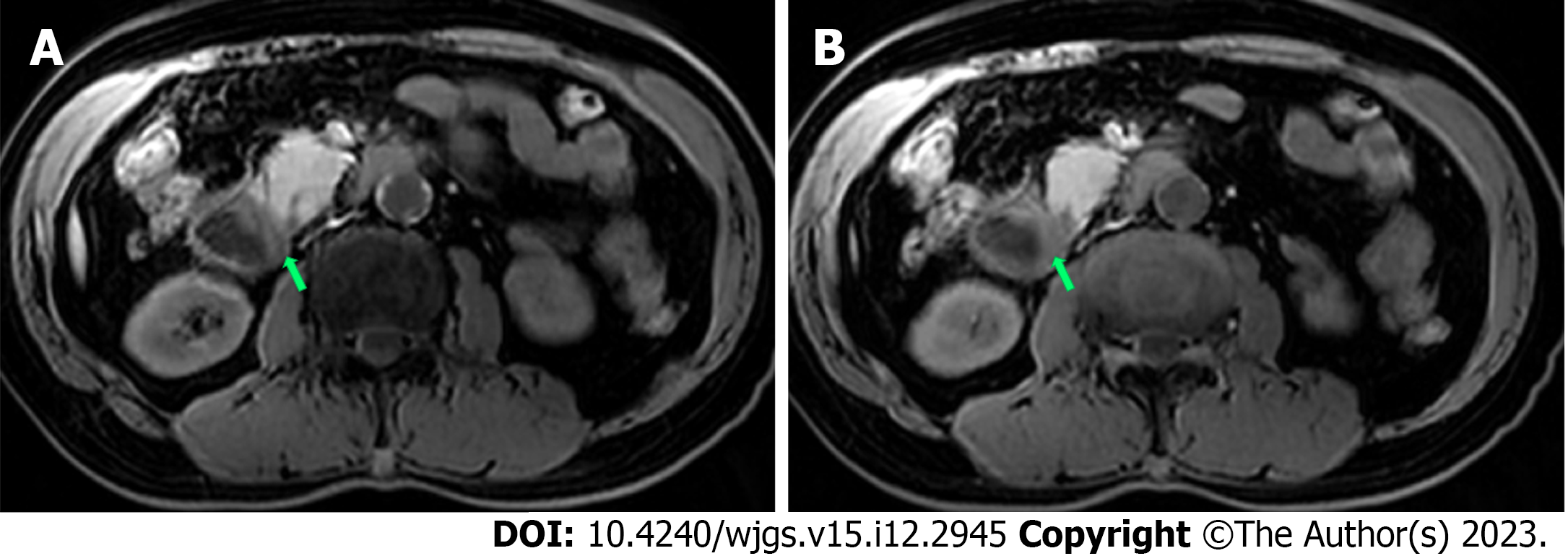

Abdominal plain computed tomography (CT) showed gastric retention and a nodule (35 mm × 23 mm) in the anterior wall of the pylorus (Figure 1), abdominal aortic wall calcification, and partial calcified endometrium inward migration (Figure 2). The CT scan showed gastric retention, an antral nodule, and possible intramural hematoma of the abdominal aorta. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed a normal bile duct and pancreatic duct, and gastric retention (Figure 3). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed multiple erosions in the distal esophagus 30 cm from the incisors, gastric retention, an antral ulcer (6 mm), and a duodenal bulbar ulcer (8 mm). The descending part of the duodenum showed slight edema and obvious luminal stenosis (Figure 4).

Uric acid and serum creatine levels were elevated; thus, the physician noted that febuxostat (20 mg once daily) and coated aldehyde oxystarch could be prescribed. The patient had pain and inflammation in his right knee and right ankle, indicating gout; thus, etoricoxib was considered an option.

Abdominal CT showed slight exudation in the descending and horizontal parts of the duodenum with broadening of the groove region, indicating local pancreatitis around the pancreatic head and gastric retention (Figure 1). An irregular nodule was found in the descending part of the duodenum with no clear demarcation (Figure 2). MRCP showed duodenal wall thickening with exudation (Figure 5) and normal bile and pancreatic ducts.

The patient presented with duodenal stenosis and multiple ulcers; thus, the physician recommended anti-ulcer drugs and enteral nutrition. If the intestinal obstruction symptoms were not relieved in 2 wk, it was advised that surgical exploration be performed.

Duodenal stenosis, duodenal obstruction, gastric ulcer, duodenal bulbar ulcer, gastric retention, reflux esophagitis, chronic pancreatitis (GP), chronic renal insufficiency, gout, intramural hematoma of the abdominal aorta, and coronary heart disease.

After admission, pantoprazole sodium (40 mg twice daily) was used to reduce gastric acid secretion. Parenteral nutrition was administered including amino acid, lipid emulsion, vitamins, and electrolytes. Octreotide acetate (0.3 mg every 12 h) was administered intravenously to reduce intestinal secretion. At 9 d after admission, we tried to insert an enteral nutrition tube through endoscopy and found obvious enema and luminal stenosis of the descending part of the duodenum. We were unsuccessful in inserting the enteral feeding tube; thus, the patient was transferred to the gastrointestinal surgery department to treat the obstruction and clarify the diagnosis.

Exploratory laparoscopy was performed and revealed an omental adhesion and hard mass with scarring in the horizontal part near the descending part of the duodenum (3 cm × 3 cm). The horizontal part of the duodenum showed obvious contraction and stenosis as well as clear gastric retention. The horizontal part of the duodenum showed adhesion with mesocolon transversum, and open surgery was required. Intraoperative frozen section analysis of lymph nodes around the pancreatic head, the hard mass with scarring in the horizontal part of the duodenum, and the mesenteric mass which showed no evidence of malignancy. The patient was diagnosed with obstruction of the horizontal part of the duodenum. Side-to-side duodenojejunostomy was performed and a gastric tube was inserted distal of the anastomotic stoma.

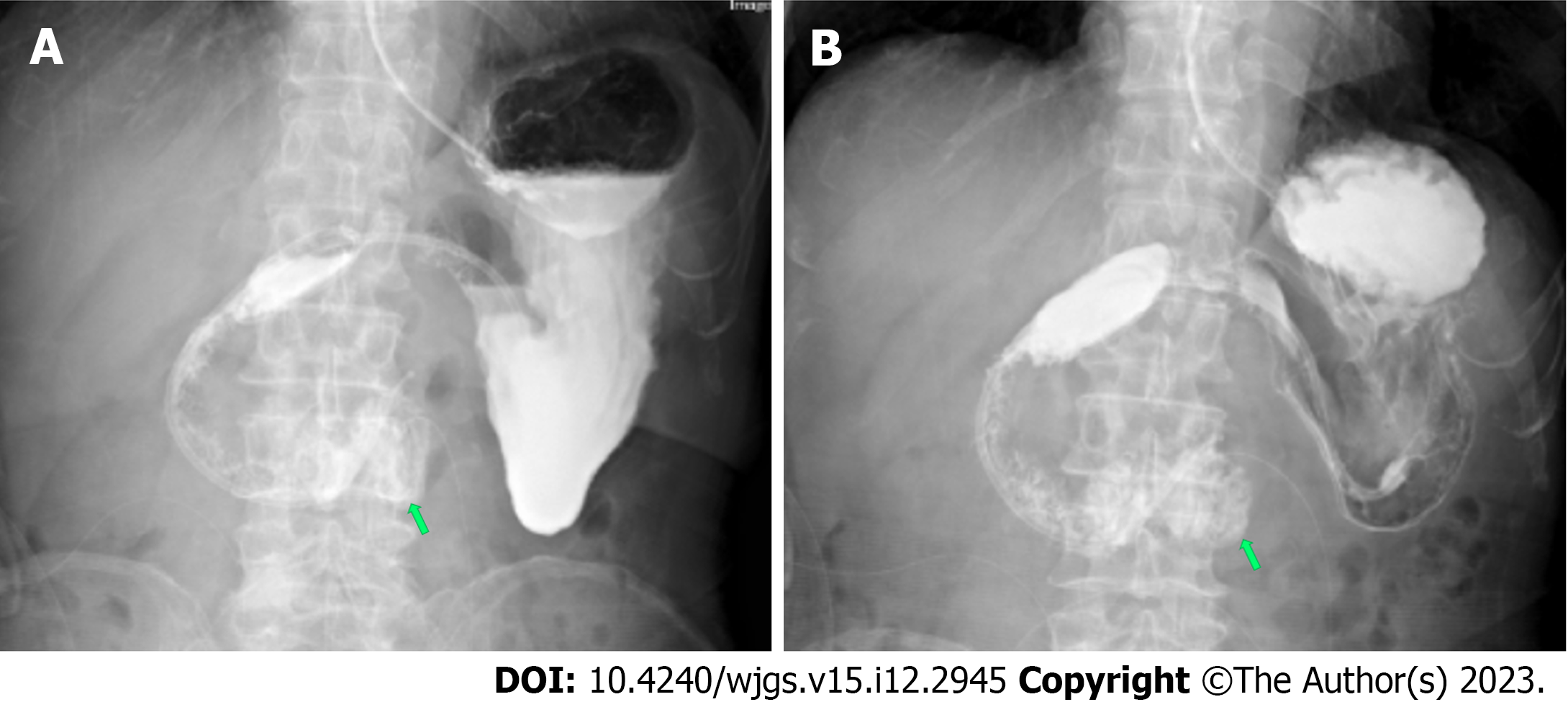

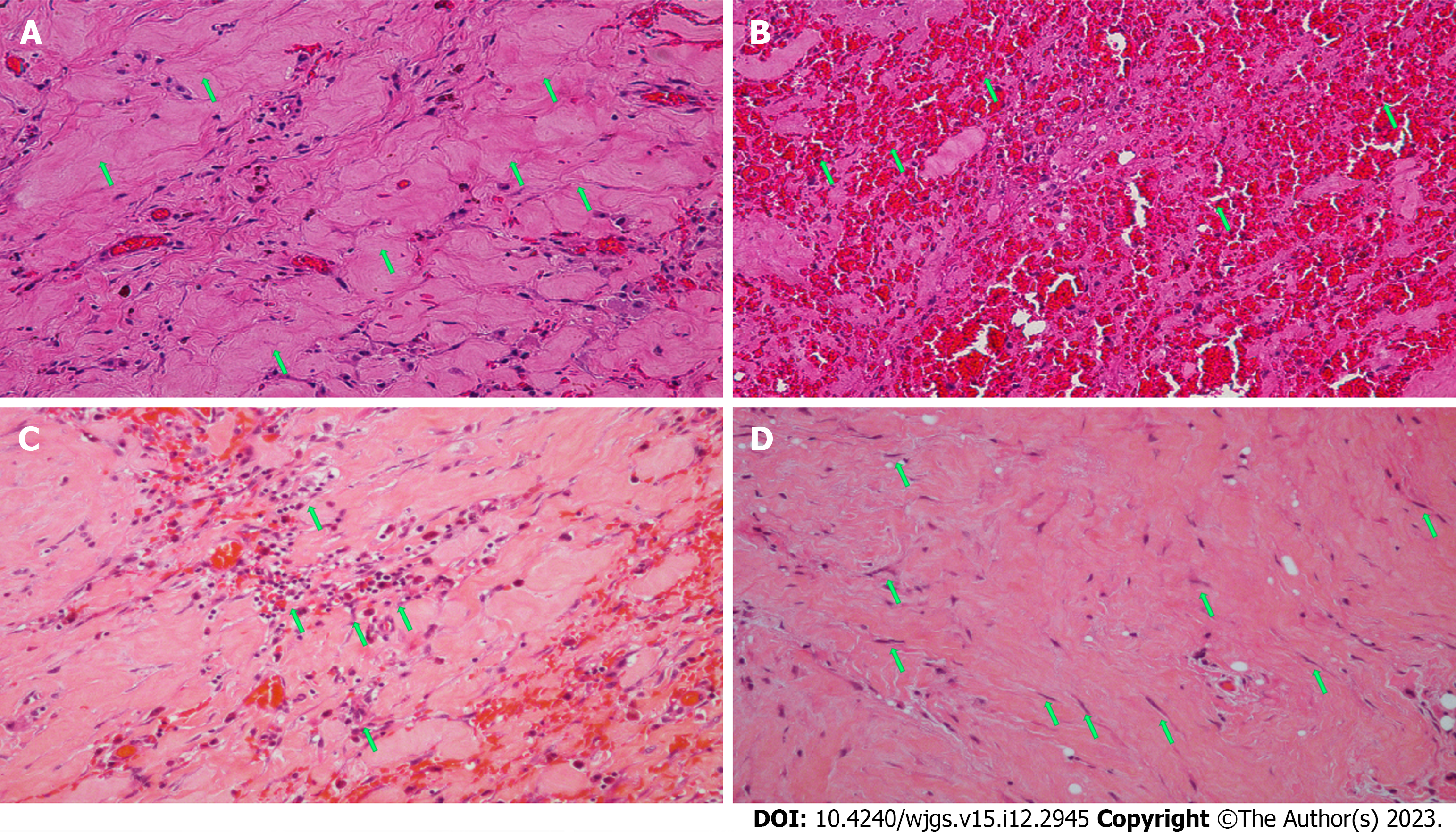

In the 10 d after surgery, parenteral nutrition, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), octreotide acetate, and anti-infective therapy were administered. The amount of drainage fluid from the gastric tube was 600-1000 mL. The patient presented with abdominal distension and vomiting after enteral nutrition. Postoperative abdominal CT showed mesangial thickening and slight exudation in the operative region and exudation and edema around the pancreatic groove region. Postoperative iodine hydrography showed obstruction of the anastomotic stoma and no visualization of the distal small intestine and the colon (Figure 6). Postoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed congestion of the anastomotic stoma and stenosis of the efferent loop (Figure 7). A jejunal nutrition tube was inserted into the efferent loop with effort. About 1 mo after surgery, iodine hydrography showed obstruction of the anastomotic stoma. Another multidisciplinary expert consultation was arranged, and the pathologist conducted histopathological evaluation. The pathology report showed massive proliferation of fibrous tissue, hyaline change and adipose tissue, chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, interstitial hemorrhage, and proliferation of spindle cells (Figure 8). Based on the radiologic and pathologic characteristics, the patient was diagnosed with GP.

Enteral nutrition therapy, PPIs, octreotide acetate, and other supporting treatment were administered. Then, the patient underwent aortic endovascular stent grafting in the cardiovascular department due to penetrating ulcer of the abdominal aorta.

After 3 mo of conservative therapy after surgery, the drainage tube had no fluid and the gastric tube was removed. Iodine hydrography showed that iodine water could enter the jejunum via the horizontal part of the duodenum (Figure 9). Then, the patient was discharged. The patient was followed up by telephone at 2 mo after discharge, and reported a normal diet and no obvious symptoms.

GP is an uncommon form of segmental pancreatitis characterized by formation of fibrous scars in the theoretic space between the C-loop of the duodenum around the pancreatic head and the common bile duct[4]. In 2004, Adsay and Zamboni[5] suggested the term “paraduodenal pancreatitis” as a unifying concept for this special form of chronic pancreatitis. According to the scope of involvement, GP is subdivided into a pure form, which only involves the anatomical groove, and a segmental form, which affects the dorsocranial portion of the pancreatic head[6]. The reported prevalence of GP is between 2.7% and 24.5% in resected specimens that were operated for chronic pancreatitis[7].

The underlying pathophysiological mechanism and etiology of GP remain to be fully elucidated, although the collective research suggests involvement of both structural and anatomic factors. GP often develops in the presence of heterotopic pancreas in the duodenal wall; it is possible that this ectopic tissue develops ischemic inflammation, especially under alcohol stimulation. Other proposed pathophysiologies include pancreatic outflow obstruction at Santorini’s duct, pancreas divisum, and hyperplasia of Brunner’s glands[8]. Long-term alcohol abuse is the most common trigger of GP.

In paraduodenal pancreatitis, the duodenum is always involved by a chronic inflammatory process in the duodenal submucosa and the adjacent pancreatic tissue. Characteristic features of GP are inflammatory thickening and fibrotic changes of the wall and stenosis of the duodenal lumen[9]. Thus, one of the characteristic manifestations are symptoms of obstruction such as vomiting secondary to gastric outlet obstruction. Reportedly, 53.5% of GP cases involve stenosis of the duodenum[6]. The classic signs of such are impaired duodenal motility, duodenal stenosis and disordered gastric emptying. For our patient, the initial symptom was vomiting and the differential diagnosis focused on duodenal stenosis, indicating that GP should be considered as a differential diagnosis of duodenal stenosis.

Regarding laboratory examinations, pancreatic enzyme levels may be slightly increased and tumor marker levels are usually normal. Endoscopy shows luminal narrowing of the duodenum with edema with or without erosions[10]. It is challenging to make a diagnosis of GP on imaging and sometimes CT can show a hypodense, poorly enhanced mass between the pancreatic head and thickened duodenal wall[11]. After the initial CT scan in our patient, little attention was paid to the groove region. A professor from the radiology department reviewed the CT scan and considered the likelihood of local pancreatitis, but the clinicians did not make a diagnosis of GP.

GP is a rare form of chronic pancreatitis, representing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to many clinicians. Despite advanced imaging techniques, even in the most professional centers, many inexperienced radiologists and gastroenterologists experience difficulty in making an accurate diagnosis of GP[12]. Our patient did not have a clear diagnosis before surgery and even during surgery, although the surgeons found a hard mass with scarring in the horizontal part near the descending part of the duodenum, a diagnosis of GP was not made. In general, GP largely remains an unfamiliar entity to most physicians, as they lack recognition of this condition. A study showed that the diagnosis of GP was delayed by weeks and months[13]. Most cases of GP are diagnosed after histopathological examination post-surgical excision. GP is described histopathologically as chronic inflammation and scarring in the anatomical space with fibrosis and proliferation of spindle cells[14].

Optimal management of GP begins with early recognition. Treatment for GP patients aims to relieve gastric outlet obstruction and resolve the presenting nutrition-related symptoms[15]. Conservative treatment options are to stop smoking/alcohol consumption, promote recovery of pancreatic function, and provide analgesics. Surgery should be performed when malignancy is suspected, gastric outlet obstruction occurs, or symptoms are refractory to conservative therapy[16]. Surgical removal of the affected “groove area” is a reliable treatment, and pancreatoduodenectomy is the most common type of resection but with relatively high mortality and morbidity[3]. A study supported recommendation for performing a preliminary gastroenterostomy to relieve symptoms of obstruction[17]. For our patient, the symptoms of intestinal obstruction were not relieved with conservative therapy, so exploratory laparoscopy was performed to clarify the diagnosis. Intra-operative histopathological examination of the biopsies did not demonstrate any malignancy so duodenojejunostomy was performed to relieve the duodenal obstruction. However, the patient presented with anastomotic obstruction postoperatively and took a long time to recover.

The intention of this case report is to make GP more familiar to radiologists and clinicians, which will be helpful in making a correct pre-operative imaging diagnosis and limit delayed diagnosis.

GP appears to manifest a specific set of clinically detectable pathognomonic features, and it should be considered among the differential diagnosis process in patients who present with signs and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction. GP often involves the descending and horizontal parts of the duodenum and causes duodenal stenosis, impaired duodenal motility, and gastric emptying due to fibrosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Brisinda G, Italy; Christodoulidis G, Greece S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Manzelli A, Petrou A, Lazzaro A, Brennan N, Soonawalla Z, Friend P. Groove pancreatitis. A mini-series report and review of the literature. JOP. 2011;12:230-233. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Potet F, Duclert N. Cystic dystrophy on aberrant pancreas of the duodenal wall. Arch Fr Mal App Dig. 1970;59:223-238. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kager LM, Lekkerkerker SJ, Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Fockens P, Boermeester MA, van Hooft JE, Besselink MG. Outcomes After Conservative, Endoscopic, and Surgical Treatment of Groove Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stolte M, Weiss W, Volkholz H, Rösch W. A special form of segmental pancreatitis: "groove pancreatitis". Hepatogastroenterology. 1982;29:198-208. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Adsay NV, Zamboni G. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a clinico-pathologically distinct entity unifying "cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas", "para-duodenal wall cyst", and "groove pancreatitis". Semin Diagn Pathol. 2004;21:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Becker V, Mischke U. Groove pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;10:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Black TP, Guy CD, White RR, Obando J, Burbridge RA. Groove Pancreatitis: Four Cases from a Single Center and Brief Review of the Literature. ACG Case Rep J. 2014;1:154-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Değer KC, Köker İH, Destek S, Toprak H, Yapalak Y, Gönültaş C, Şentürk H. The clinical feature and outcome of groove pancreatitis in a cohort: A single center experience with review of the literature. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022;28:1186-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pallisera-Lloveras A, Ramia-Ángel JM, Vicens-Arbona C, Cifuentes-Rodenas A. Groove pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:280-288. [PubMed] |

| 10. | DeSouza K, Nodit L. Groove pancreatitis: a brief review of a diagnostic challenge. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:417-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gabata T, Kadoya M, Terayama N, Sanada J, Kobayashi S, Matsui O. Groove pancreatic carcinomas: radiological and pathological findings. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1679-1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Valentini G, Surace M, Grosso S, Vernetto A, Serra AM, Andria I, Mazzucco D. Groove pancreatitis. Minerva Gastroenterol (Torino). 2023;69:436-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Teo J, Suthananthan A, Pereira R, Bettington M, Slater K. Could it be groove pancreatitis? A frequently misdiagnosed condition with a surgical solution. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92:2167-2173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hungerford JP, Neill Magarik MA, Hardie AD. The breadth of imaging findings of groove pancreatitis. Clin Imaging. 2015;39:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Frey CF, Mayer KL. Comparison of local resection of the head of the pancreas combined with longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (frey procedure) and duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head (beger procedure). World J Surg. 2003;27:1217-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tezuka K, Makino T, Hirai I, Kimura W. Groove pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2010;27:149-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Latham J, Sanjay P, Watt DG, Walsh SV, Tait IS. Groove pancreatitis: a case series and review of the literature. Scott Med J. 2013;58:e28-e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |