Published online Dec 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i12.2938

Peer-review started: August 29, 2023

First decision: September 29, 2023

Revised: October 11, 2023

Accepted: November 10, 2023

Article in press: November 10, 2023

Published online: December 27, 2023

Processing time: 120 Days and 4 Hours

Klebsiella variicola (K. variicola) is a member of the Klebsiella genus and is often misidentified as Klebsiella pneumoniae. In this report, we present a rare case of invasive liver abscess caused by K. variicola.

We report a rare case of liver abscess due to K. variicola. A 57-year-old female patient presented with back pain for a month. She developed a high-grade fever associated with chills, and went into a coma and developed shock. The clinical examinations and tests after admission confirmed a diagnosis of primary liver abscess caused by K. variicola complicated by intracranial infection and septic shock. The patient successfully recovered following early percutaneous drainage of the abscess, prompt appropriate antibiotic administration, and timely open surgical drainage.

This is a case of successful treatment of invasive liver abscess syndrome caused by K. variicola, which has rarely been reported. The findings of this report point to the need for further study of this disease.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of liver abscess caused by Klebsiella variicola (K. variicola) complicated by intracranial infection and septic shock. Invasive liver abscess syndrome was mainly caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in previous reports. The patient successfully recovered following early percutaneous drainage of the abscess, prompt appropriate antibiotic administration, and timely open surgical drainage. Regarding the information in the case, we consider that more attention should be given to K. variicola in clinical practice.

- Citation: Zhang PJ, Lu ZH, Cao LJ, Chen H, Sun Y. Successful treatment of invasive liver abscess syndrome caused by Klebsiella variicola with intracranial infection and septic shock: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(12): 2938-2944

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i12/2938.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i12.2938

Klebsiella variicola (K. variicola) was initially believed to be a plant-associated distant lineage of Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae)[1]. Currently, K. variicola is gaining recognition as a cause of several human infections. Nevertheless, its virulence profile has not been fully characterized. The clinical significance of K. variicola infection is obscure. K.variicola is very difficult to differentiate from K. pneumoniae by imprecise detection methods, which have underestimated its real prevalence. In fact, approximately 20% of the human isolates assumed to be K. pneumoniae were in fact K. variicola or Klebsiella quasipneumoniae[2]. During the last two decades, invasive liver abscess syndrome due to K. pneumoniae has been increasingly reported worldwide, especially in the Asia Pacific region, and it is associated with high morbidity and mortality[3]. However, invasive liver abscess syndrome caused by K. variicola is still rarely described. Intriguingly, several methods (such as molecular, genomic, and proteomic methods) have been developed to correctly identify this species. In this paper, we present a case of invasive liver abscess syndrome due to K. variicola complicated by intracranial infection and septic shock. There should be increasing awareness among clinicians about this emerging invasive syndrome due to K. variicola.

A 57-year-old female patient was referred to our hospital with a high-grade fever associated with chills for 3 d.

The patient presented with a high fever associated with chills for 3 d and then developed shock and went into a coma.

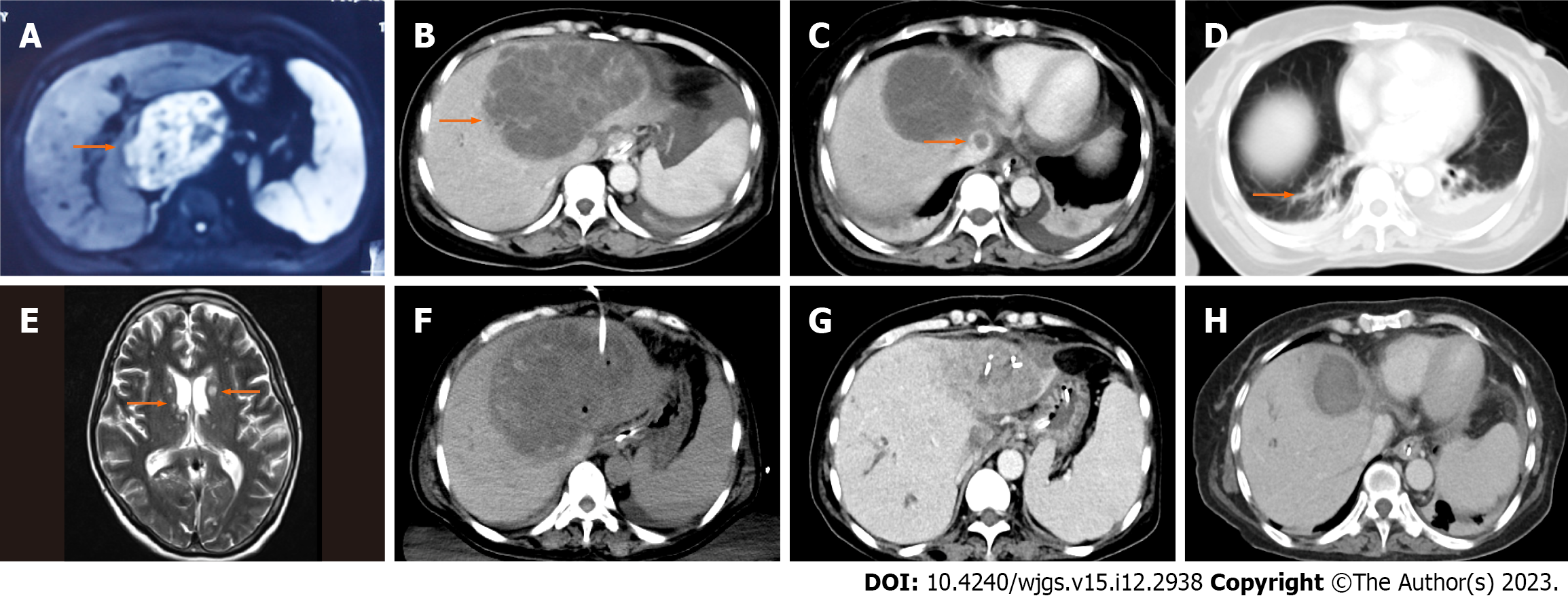

One month prior, the patient complained of right-sided back pain and was diagnosed with liver abscess based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver (Figure 1A). She was treated with antibiotics (third generation cephalosporins) for 2 wk in a local hospital and then was discharged home.

The patient had no family history of cancer. She had no history of diabetes mellitus or immunodeficiency and was neither a smoker nor a drinker.

When admitted, the patient’s initial vital signs were: Body temperature, 37.3 °C; heart rate, 111 beats per minute; blood pressure, 136/85 mmHg; respiratory rate, 30 breaths per minute. She had an oxygen saturation of 98% on 3 L/min oxygen. She was in a condition of somnolence. Physical examination of the heart and lung did not reveal abnormalities. Tenderness could be elicited in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The neck was stiff, and Kernig’s sign was positive.

Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 11.77 × 109/L with an elevated neutrophil percentage of 90.4%. The concentration of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein was 214.6 mg/L. The results of the liver function test were as follows: Aspartate aminotransferase at 104 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase at 111 IU/L. There were no significant ab

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a single abscess in the left lobe of the liver (125 mm × 97 mm) (Figure 1B) and a thrombus in the inferior vena cava (Figure 1C). A chest CT scan showed focal small patchy infiltrates in both lungs (Figure 1D).

On the 2nd d after admission, she presented with a persistent high fever and was in a coma. Considering the possibility of intracranial infection, a cranial MRI examination was performed. There were multiple abnormally high signals on T2-weighted images in the whole brain (Figure 1E).

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was invasive liver abscess syndrome caused by a K. variicola infection.

Considering the diagnosis of invasive liver abscess syndrome with septic shock and intracranial infection, empirical treatment with intravenous meropenem (2000 mg q8h) was immediately initiated. Furthermore, emergency ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage (10F) of the liver abscess was performed (Figure 1F), which drained 900 mL of yellow pus over the first 24 h. The liver aspirate was submitted for bacterial culture.

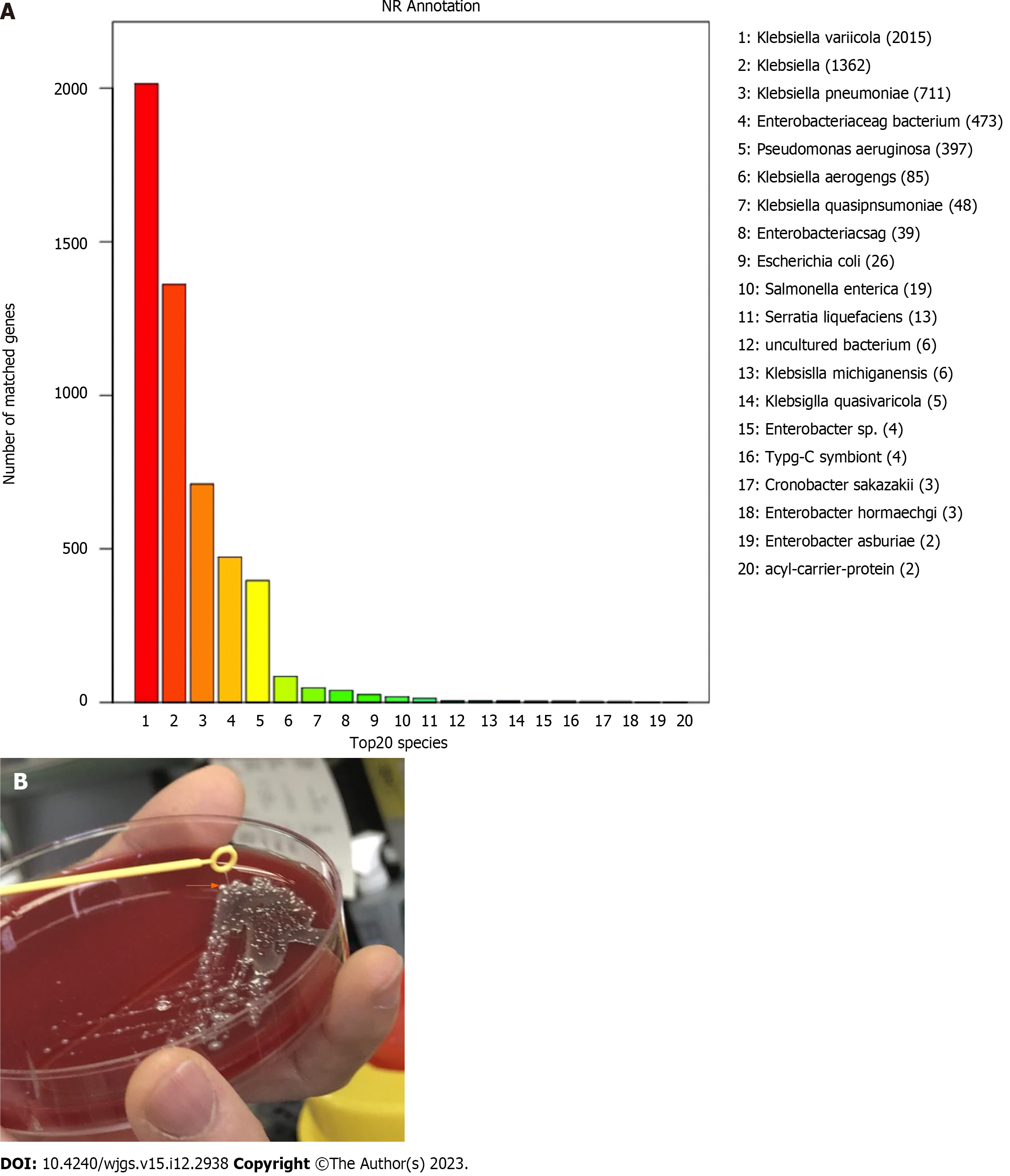

On the 5th d after admission, K. variicola was isolated from two independent samples of blood and liver pus. These results were different from those of blood cultures from the local hospital. Furthermore, the isolate was confirmed by whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (Figure 2A). The strain showed a hypermucoviscous phenotype, which was investigated by the string test (Figure 2B). The isolate was resistant to ceftriaxone and cefoxitin but susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulanate, aminoglycosides, cotrimoxazole, and meropenem. Therefore, antibiotic treatment with meropenem was continued.

The drainage volume of the liver abscess gradually decreased, but the two hemogram parameters, the white blood cell count and neutrophil percentage, remained at considerably high levels. On the 10th d, surgical drainage of the liver abscess was performed. Following aspiration of approximately 800 mL of the purulent fluid, a dual drainage tube (28F) was inserted into the bottom of the abscess. The cavity of the abscess was rinsed with saline, and continuous negative pressure was used to drain fluid through the tube.

In the next few days, her critical condition improved, and she gradually recovered her consciousness. On the 23rd d, she was transferred to the general ward and continued receiving antibiotic therapy. At 18 d after the surgery, CT reexamination revealed a marked reduction in the size of the abscess (Figure 1G), and the inferior vena cava thrombus had completely disappeared (Figure 1H).

The patient was discharged with a drainage tube (12F) due to ongoing bile leakage, while antibiotic therapy (cotrimoxazole) was continued in the outpatient clinic due to an intracranial infection. A telephone follow-up after 3 mo showed that she had recovered with no neurologic sequelae, and the antibiotic treatment was discontinued. The drainage volume gradually decreased, and the latest abdominal ultrasound showed no lesions in her liver.

Bacterial liver abscess is a potentially life-threatening disease. It is caused by various organisms, including Escherichia coli, K. pneumoniae, Streptococcus anginosus, and anaerobes such as Bacteroides. In recent years, the incidence rate of bacterial liver abscess has been rising, especially those caused by K. pneumoniae. Primary liver abscess (KLA) caused by K. pneumoniae emerged in East Asia but has been increasingly reported in other parts of the world[4]. Approximately 13% of patients with KLA have septic metastatic ocular or central nervous system lesions, which are associated with high morbidity and mortality[4]. K. variicola is a relatively newly discovered bacterium that was first described in 2004[1]. Due to its new discovery and close resemblance to K. pneumoniae, it is often misclassified as K. pneumoniae[5]. The clinical significance of K. variicola infection has been observed by imprecise detection methods, which underestimate its real prevalence.

K. variicola, as well as K. pneumoniae, is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for various infections, such as bloodstream infections, respiratory tract infections, and urinary tract infections[6,7]. In general, K. variicola isolates displayed lower antibiotic resistance rates than K. pneumoniae[8]. However, this fact was not associated with a better treatment response[9,10]. In fact, infections caused by K. variicola are more severe than those caused by K. pneumoniae[6].

Historically, K. pneumoniae was divided into three different phylogenetic groups based on sequencing of gyrA and parC genes. KpI was the largest cluster, which included K. pneumoniae subspecies; the KpII and KpIII clusters included K. quasipneumoniae and K. variicola, respectively[11]. Unfortunately, K. variicola was likely under-recognized because of its similar phylogenetic and biochemical properties to K. pneumoniae. Although biochemical techniques could be suggestive, these tests were not conclusive given that overlap might occur[11].

At present, the only definitive method to differentiate species is WGS or targeted sequencing[12]. Currently, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has been widely used for the identification of bacterial species as it is a fast and economical technique. The most up-to-date versions of MALDI-TOF MS databases include reference spectra that allow to differentiate K. varicola from K. pneumonieae. In our case, K. variicola was identified at our hospital by using MALDI-TOF MS, Bruker library version 6.0.0.0 (Bruker Autoflex MALDI TOF-MS, Germany), but the results of the blood culture in the local hospital were K. pneumoniae. Considering that the results were inconsistent, the genomic DNA of the bacteria isolated from the pus culture was extracted using QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions and the isolate was identified as K. variicola by WGS. WGS was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq PE150 (Illumina, San Diego, United States) and the draft genome sequence was annotated using the microbial genome database which contains a large collection of microbial genomes from NCBI. This Whole Genome Sequencing project has been deposited in National Genomics Data Center under the accession No. PRJCA020759 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn). The prevalence of K. variicola is unclear, mainly due to the difficulties in identifying this species or its misidentification[5]. Although the management of this case was not affected by misidentification, correct species identification carried important prognostic and epidemiologic implications. As it has been previously suggested that patients with K. variicola have a poor prognosis, hypermucoid strains often have the ability to spread from the site of infection to other areas, making their removal and treatment difficult[13].

Invasive liver abscess syndrome is associated with both host and virulence factors. A striking finding of this study is the hypermucoviscous phenotype of K. variicola. Emerging evidence has demonstrated an association between the hypermucoviscous phenotype and invasive isolates of K. pneumoniae. It has been increasingly reported, including in young and immunocompetent patients, that the hypermucoviscous phenotype is significantly associated with the capacity of K. pneumoniae to cause serious infections, such as pyogenic liver abscess syndrome and metastatic dissemination to other parts of the body, including the eyes, central nervous system, and lungs[14-16]. The hypermucoviscous phenotype was present in the encapsulated strains of K. pneumoniae (mostly K1 and to a lesser extent K2), which produced vast amounts of extracapsular polysaccharide constituting a mucoviscous web that protected these strains from phagocytosis by neutrophils and from killing by serum complement[17,18]. To the best of our knowledge, there have been few reports concerning K. variicola with the hypermucoviscous phenotype causing invasive liver abscess syndrome[19]. Apart from virulence factors, KLA has been significantly associated with underlying diabetes mellitus compared to non-K. pneumonia primary liver abscess, especially in those who developed metastatic infection[20]. K. variicola has also been associated with infections in immunocompromised individuals. Some comorbidities, such as systemic lupus erythematous, cancer, diabetes mellitus, hepatobiliary diseases, solid organ transplantation, and alcoholism, have been reported in several studies[9,10]. In this case, our patient was a healthy middle-aged woman with no history of diabetes mellitus or immunodeficiency. However, the laboratory investigations after admission showed that the patient’s random blood glucose level was as high as 16.34 mmol/L, and her glycosylated hemoglobin was mildly higher (6.5%). It is generally accepted that a high blood glucose level can reduce phagocyte chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and bactericidal activity and can contribute to bacterial growth and a compromised host defense system[21]. Our case suggested that K. variicola infections could also occur in immunocompetent patients.

There are currently no definite guidelines for managing invasive liver abscesses. The basic consensus is the combination of early percutaneous drainage or open (laparoscopic) surgical drainage of the abscess and the prompt administration of appropriate antibiotics. As interventional radiology advances, percutaneous drainage has become more widespread. However, aggressive hepatic resection has been found to be more beneficial to patients with an acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II score of 15 or greater. Our patient benefited from the empirically and sufficiently intravenous use of meropenem and early percutaneous drainage of abscesses. However, the patient’s condition did not improve in the following days. Surgical drainage was performed in a timely manner considering that the liver abscess was relatively large (larger than 10 cm in diameter). Fortunately, the surgery was successful, and the patient was cured.

We have presented a rare case to raise clinician awareness of this worldwide emerging invasive syndrome. There is no doubt that invasive liver abscess syndrome caused by K. variicola is a devastating disease that can progress rapidly. In addition, urgent diagnosis and treatment are very important. Regarding the information raised in this case, we suggest that K. variicola, as an underappreciated pathogen, should be given more attention in clinical practice.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kvolik S, Croatia; Pitondo-Silva A, Brazil S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Rosenblueth M, Martínez L, Silva J, Martínez-Romero E. Klebsiella variicola, a novel species with clinical and plant-associated isolates. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2004;27:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Martin RM, Bachman MA. Colonization, Infection, and the Accessory Genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 504] [Cited by in RCA: 581] [Article Influence: 83.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tseng CW, Chen YT, Lin CL, Liang JA. Association between chronic pancreatitis and pyogenic liver abscess: a nationwide population study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:505-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rodríguez-Medina N, Barrios-Camacho H, Duran-Bedolla J, Garza-Ramos U. Klebsiella variicola: an emerging pathogen in humans. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8:973-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maatallah M, Vading M, Kabir MH, Bakhrouf A, Kalin M, Nauclér P, Brisse S, Giske CG. Klebsiella variicola is a frequent cause of bloodstream infection in the stockholm area, and associated with higher mortality compared to K. pneumoniae. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Long SW, Linson SE, Ojeda Saavedra M, Cantu C, Davis JJ, Brettin T, Olsen RJ. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Human Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates Reveals Misidentification and Misunderstandings of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella variicola, and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae. mSphere. 2017;2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Garza-Ramos U, Moreno-Dominguez S, Hernández-Castro R, Silva-Sanchez J, Barrios H, Reyna-Flores F, Sanchez-Perez A, Carrillo-Casas EM, Sanchez-León MC, Moncada-Barron D. Identification and Characterization of Imipenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Susceptible Klebsiella variicola Isolates Obtained from the Same Patient. Microb Drug Resist. 2016;22:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Seki M, Gotoh K, Nakamura S, Akeda Y, Yoshii T, Miyaguchi S, Inohara H, Horii T, Oishi K, Iida T, Tomono K. Fatal sepsis caused by an unusual Klebsiella species that was misidentified by an automated identification system. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:801-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Berry GJ, Loeffelholz MJ, Williams-Bouyer N. An Investigation into Laboratory Misidentification of a Bloodstream Klebsiella variicola Infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2793-2794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alves MS, Dias RC, de Castro AC, Riley LW, Moreira BM. Identification of clinical isolates of indole-positive and indole-negative Klebsiella spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3640-3646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fontana L, Bonura E, Lyski Z, Messer W. The Brief Case: Klebsiella variicola-Identifying the Misidentified. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Garza-Ramos U, Silva-Sanchez J, Barrios H, Rodriguez-Medina N, Martínez-Barnetche J, Andrade V. Draft Genome Sequence of the First Hypermucoviscous Klebsiella variicola Clinical Isolate. Genome Announc. 2015;3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Choby JE, Howard-Anderson J, Weiss DS. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae - clinical and molecular perspectives. J Intern Med. 2020;287:283-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 79.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vila A, Cassata A, Pagella H, Amadio C, Yeh KM, Chang FY, Siu LK. Appearance of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome in Argentina: case report and review of molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis. Open Microbiol J. 2011;5:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de Campos TA, Gonçalves LF, Magalhães KG, de Paulo Martins V, Pappas Júnior GJ, Peirano G, Pitout JDD, Gonçalves GB, Furlan JPR, Stehling EG, Pitondo-Silva A. A Fatal Bacteremia Caused by Hypermucousviscous KPC-2 Producing Extensively Drug-Resistant K64-ST11 Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brazil. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cerwenka H. Pyogenic liver abscess: differences in etiology and treatment in Southeast Asia and Central Europe. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2458-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rivero A, Gomez E, Alland D, Huang DB, Chiang T. K2 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae causing a liver abscess associated with infective endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:639-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Harada S, Aoki K, Yamamoto S, Ishii Y, Sekiya N, Kurai H, Furukawa K, Doi A, Tochitani K, Kubo K, Yamaguchi Y, Narita M, Kamiyama S, Suzuki J, Fukuchi T, Gu Y, Okinaka K, Shiiki S, Hayakawa K, Tachikawa N, Kasahara K, Nakamura T, Yokota K, Komatsu M, Takamiya M, Tateda K, Doi Y. Clinical and Molecular Characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates Causing Bloodstream Infections in Japan: Occurrence of Hypervirulent Infections in Health Care. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:e01206-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang J, Yan Y, Xue X, Wang K, Shen D. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae and non-Klebsiella pneumoniae pathogens in Beijing: a retrospective analysis. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:1088-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lin YT, Wang FD, Wu PF, Fung CP. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in diabetic patients: association of glycemic control with the clinical characteristics. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |