Published online Nov 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i11.2537

Peer-review started: July 21, 2023

First decision: August 15, 2023

Revised: September 27, 2023

Accepted: October 30, 2023

Article in press: October 30, 2023

Published online: November 27, 2023

Processing time: 128 Days and 23.2 Hours

Patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) are at risk of developing complications such as perianal fistulas. Patients with Crohn’s perianal fistulas (CPF) are affected by fecal incontinence (FI), bleeding, pain, swelling, and purulent perianal discharge, and generally face a higher treatment burden than patients with CD without CPF.

To gain insights into the burden of illness/quality of life in patients with CPF and their treatment preferences and satisfaction.

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted in patients with CD aged 21-90 years via a web-enabled questionnaire in seven countries (April-August 2021). Patients were recruited into three cohorts: Cohort 1 included patients without perianal fistulas; cohort 2 included patients with perianal fistulas without fistula-related surgery; and cohort 3 included patients with perianal fistulas and fistula-related surgery. Validated patient-reported outcome measures were used to assess quality of life. Drivers of treatment preferences were measured using a discrete choice experiment (DCE).

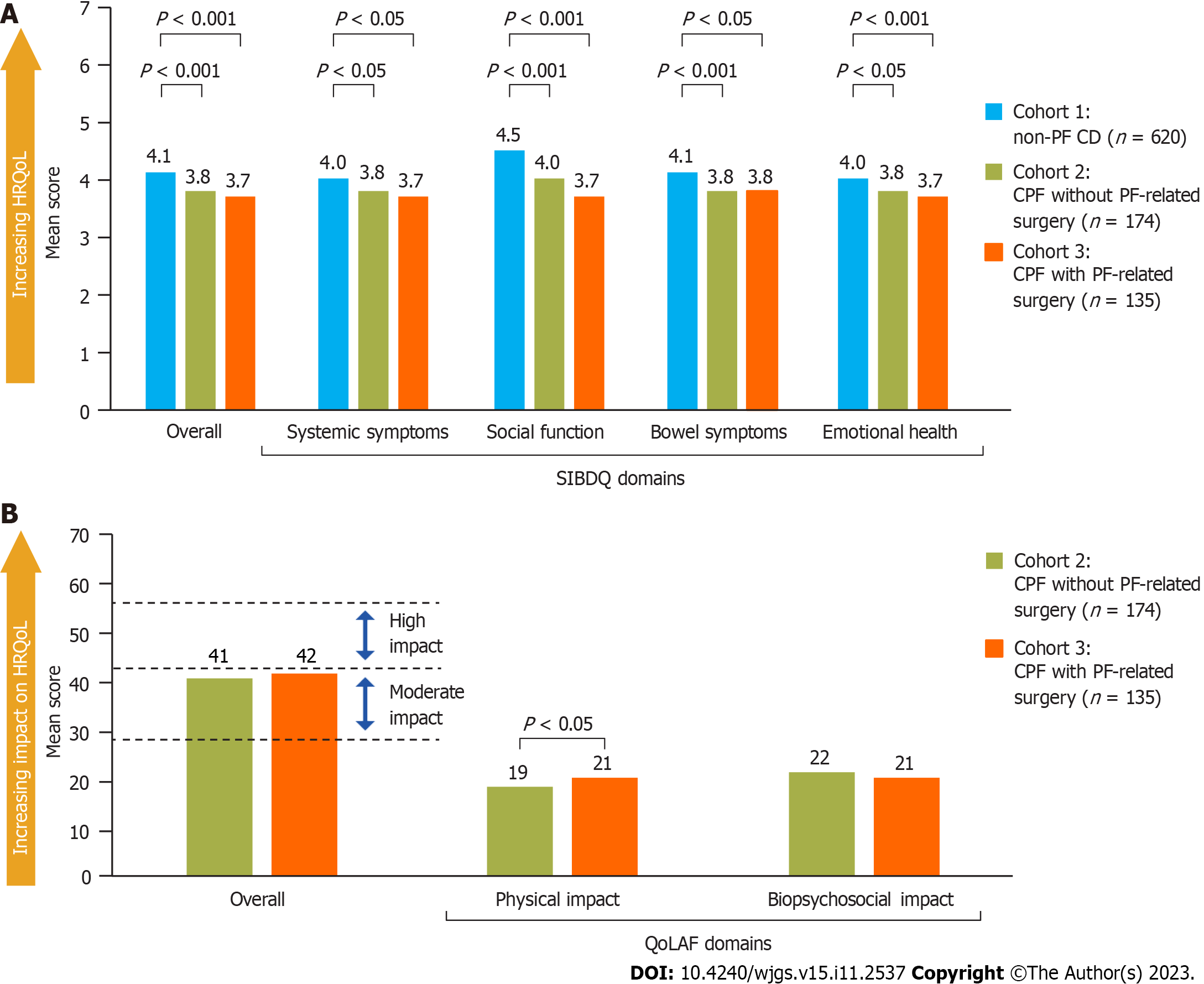

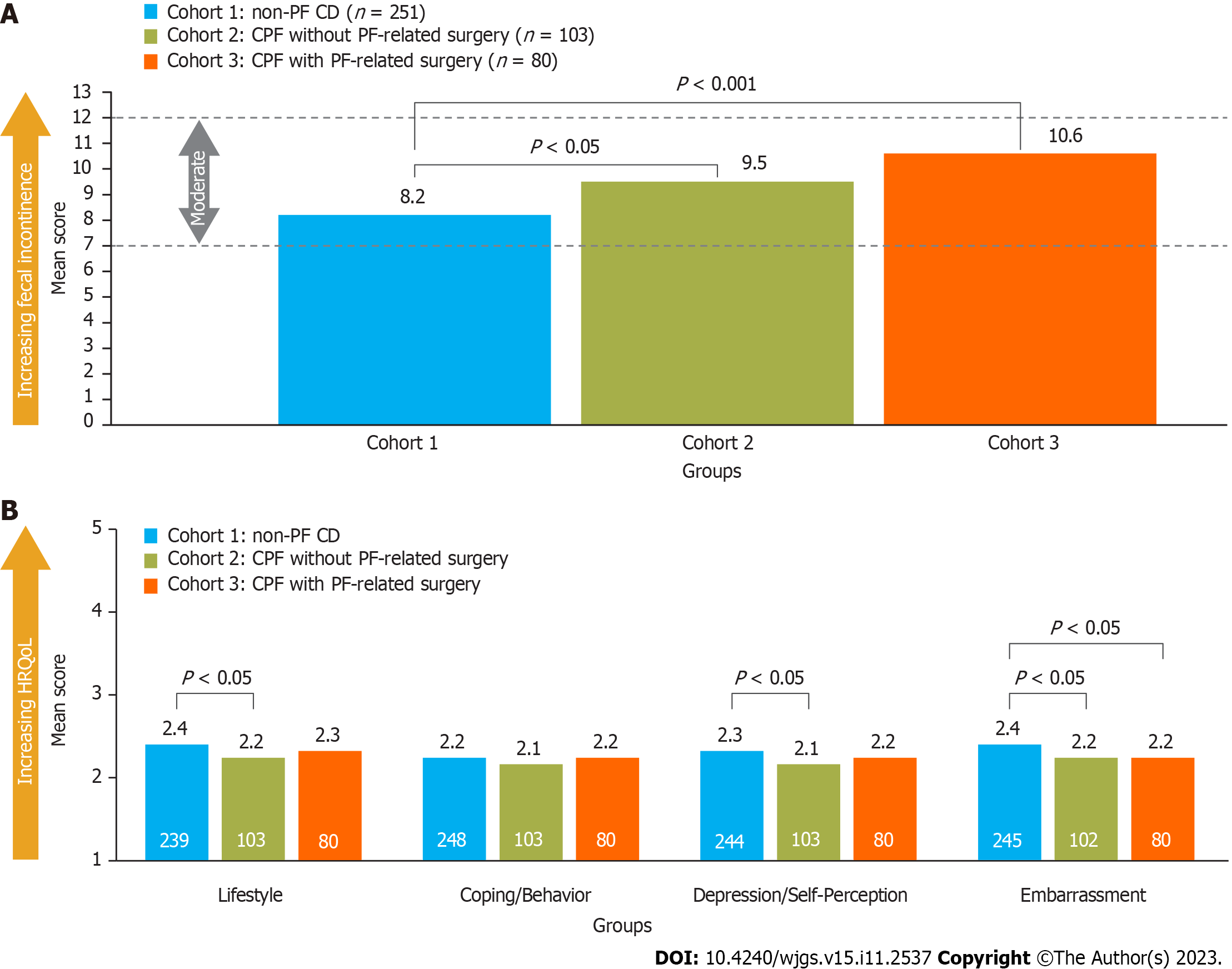

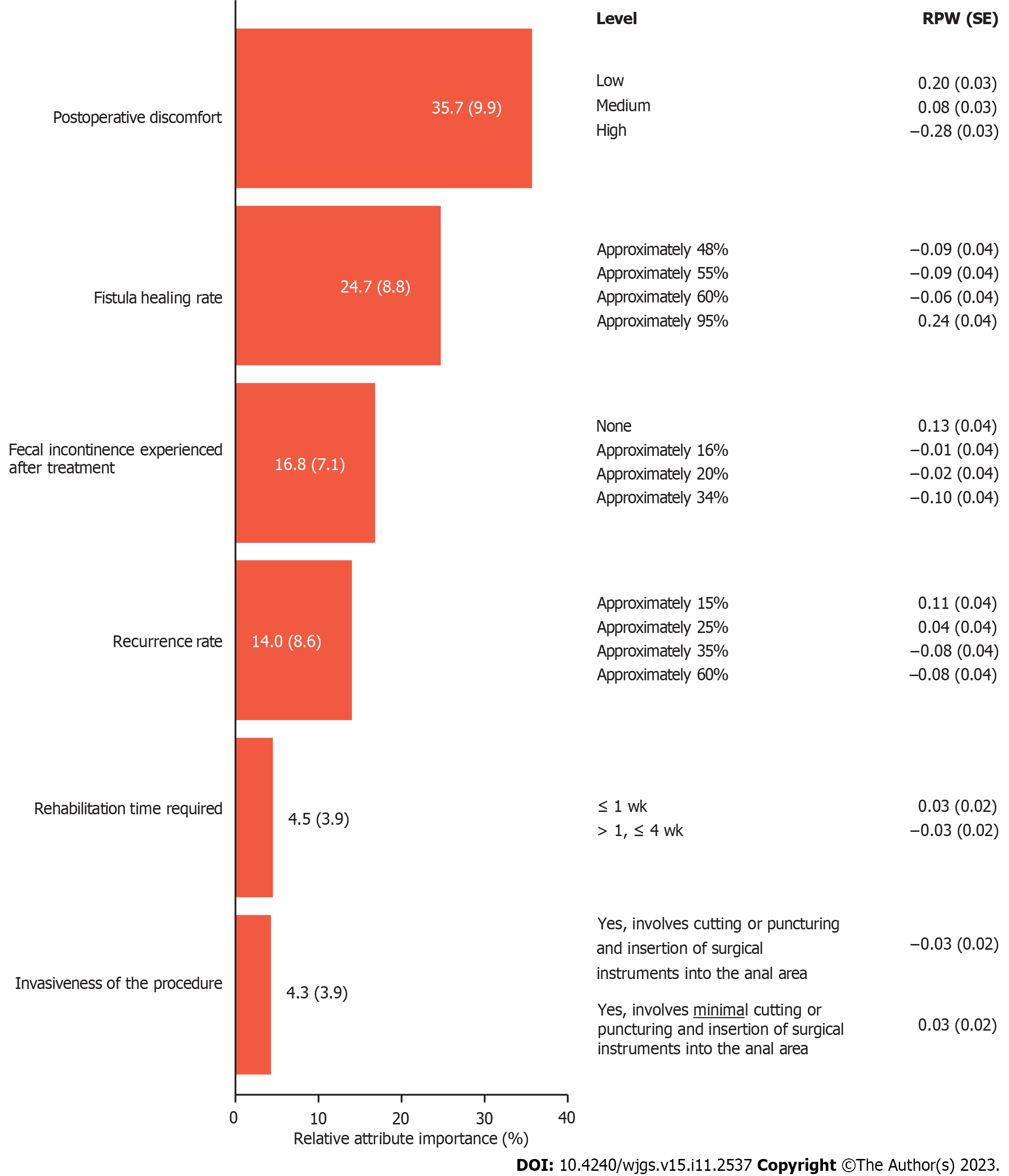

In total, 929 patients were recruited (cohort 1, n = 620; cohort 2, n = 174; cohort 3, n = 135). Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire scores were worse for patients with CPF (cohorts 2 and 3) than for those with CD without CPF (cohort 1): Mean score 3.8 and 3.7 vs 4.1, respectively, (P < 0.001). Similarly, mean Revised FI and FI Quality of Life scores were worse for patients with CPF than for those with CD without CPF. Quality of Life with Anal Fistula scores were similar in patients with CPF with or without CPF-related surgery (cohorts 2 and 3): Mean score 41 and 42, respectively. In the DCE, postoperative discomfort and fistula healing rate were the most important treatment attributes influencing treatment choice: Mean relative importance 35.7 and 24.7, respectively.

The burden of illness in CD is significantly higher for patients with CPF and patients rate lower postoperative discomfort and higher healing rates as the most desirable treatment attributes.

Core Tip: This is the largest known observational study to quantify the burden of illness associated with Crohn’s perianal fistulas (CPF) across multiple countries, utilizing a comprehensive set of outcomes including symptom burden and impacts, and treatment experience, satisfaction, and preferences. This study confirmed that the burden of illness for patients with Crohn’s disease is significantly higher for those with CPF than those without. Patients with CPF rated lower postoperative discomfort and higher healing rates as the most desirable treatment attributes. Assessing patient treatment preferences is key to helping healthcare professionals with clinical management and treatment decisions associated with CPF.

- Citation: Karki C, Athavale A, Abilash V, Hantsbarger G, Geransar P, Lee K, Milicevic S, Perovic M, Raven L, Sajak-Szczerba M, Silber A, Yoon A, Tozer P. Multi-national observational study to assess quality of life and treatment preferences in patients with Crohn’s perianal fistulas. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(11): 2537-2552

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i11/2537.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i11.2537

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, with an annual global incidence of up to 20.2 cases per 100000 persons[1,2]. Patients with CD are at risk of developing complications such as perianal fistulas (PF), which are estimated to develop in up to 50% of patients[3,4]. It has been estimated that up to 73% of patients with Crohn’s perianal fistulas (CPF) are affected by fecal incontinence (FI)[5-7]. Symptoms specifically related to fistulas often include bleeding, pain, swelling, and purulent perianal discharge, and patients with CPF generally face a higher treatment burden than patients with CD without PF[3,8-10].

There are many treatments utilized for the care of patients with CPF that are aimed at initial disease control, symptom reduction, or fistula healing, depending on the nature of the fistulas and surrounding perianal disease, overall luminal disease, and the personal treatment goals. Treatment options for the management of CPF include seton placement for drainage, pharmacological therapies (e.g., antibiotics, immunomodulators, and anti-tumor necrosis factor agents), and surgical procedures (e.g., ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract, advancement flaps, and newer procedures including fistula plugs, fibrin glue, and fistula tract laser closure)[8,11]; however, with limited evidence to support the use of these treatments, there is a lack of consensus on the standard of care for patients with CPF[3,12-15]. Most treatments for CPF are associated with low rates of remission and high rates of relapse or treatment failure, leading to patients undergoing repeated cycles of treatments and surgeries[4,16-18].

Published studies on the burden of illness and quality of life for patients with CPF are limited[4]. This cross-sectional multi-country observational study was conducted to gain a more in-depth understanding of the burden of illness of CPF through a comparison of the disease burden, treatment experiences, preferences and satisfaction, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients with CPF and patients with CD without PF. Furthermore, this study compared these outcomes for patients with and without PF-related surgery to assess the impact of PF-related surgery on the burden on CPF.

Assessing patient treatment preferences is key to helping healthcare professionals with clinical management and treatment decisions associated with CPF. Given the heterogeneous treatment options available to patients with CPF (pharmacological therapies, seton placement/palliative treatment, surgical options, and stem cell therapies), this study assessed patients’ treatment preferences and satisfaction using a discrete choice experiment (DCE) methodology. DCEs are designed to elicit preferences in the healthcare setting and have been utilized increasingly over the past decade[19-23]. In a DCE, patients are asked to select their preferred choice from a set of hypothetical treatment profiles that describe attributes such as treatment efficacy, treatment side effects, or health states to identify the relative importance of these treatment attributes and an underlying utility function[24]. To our knowledge, this study includes the first DCE conducted in a population of patients with CPF.

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted via a 45-min web-enabled patient questionnaire in seven countries (France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Japan) from April 2021 to August 2021. Patient recruitment was undertaken by a third-party recruitment company, Dynata LLC (New York, United States). Patients in Dynata’s online panel of patients were invited to participate based on profile data including self-reported physician-diagnosed CD. The questionnaire was pre-tested by conducting patient interviews (n = 7, 60 min each) across key countries to assess whether the comprehension of the questions was as intended and to identify potential sources of response error. Patients aged 21-90 years at the time of consent were eligible if they had a self-reported physician diagnosis of CD and had either been treated for CPF in the past 12 mo (CPF cohorts) or never experienced PF (non-PF CD cohort). Patients with a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis were excluded.

Based on maximum feasibility, research questions, and the objectives of the study, the global target study size was N = 855 (n = 150 Canada, France, Germany, and United Kingdom; n = 120 Spain; n = 90 Australia; n = 45 Japan). Patients were recruited into one of three cohorts based on their responses to carefully tailored screening questions prior to entering the web-enabled questionnaire: Cohort 1 included patients with CD who had never experienced perianal fistulas (non-PF CD), cohort 2 included patients with CPF who had no PF-related surgery in the past 12 mo but may have received pharmacotherapy and/or seton placement, and cohort 3 included patients with CPF who had PF-related surgery in the past 12 mo (with or without pharmacotherapy and/or seton placement). For the purposes of this study, only reparative/interventional PF-related procedures were considered as surgery (seton placement was not included in this description because almost all patients with CPF will undergo seton placement); hence patients in cohort 2 (without PF-related surgery) as well as patients in cohort 3 may have received seton placement.

The co-primary objectives of the study were to compare the HRQoL and treatment experiences, preferences, and satisfaction of patients with CD with and without CPF in an international study across seven countries, using standard validated general and disease-specific patient-reported outcomes measures and a DCE.

The secondary objective of the study was to compare HRQoL and treatment experiences, preferences, and satisfaction among patients with CPF who had PF-related surgery (with or without pharmacotherapy) with those patients with CPF who had no PF-related surgery in the past 12 mo.

Patient-reported outcome measures were used to assess the HRQoL (disease specific), FI, and its impact on HRQoL, and general health status of participating patients.

The HRQoL measures administered in this study included the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ)[25] and the Quality of Life in patients with Anal Fistula (QoLAF) questionnaire[26]. SIBDQ is a 10-item questionnaire designed to assess the impact of inflammatory bowel diseases in general on HRQoL, with each item scored on a 7-point scale (1 = poor health-related quality of life, 7 = optimum health-related quality of life). The recall period was 2 wk, and a difference of 9 points was considered a clinically significant difference based on total score (prior to dividing the total score by 10)[26]. The QoLAF questionnaire, designed to specifically assess the impact of anal fistulas on HRQoL, is composed of physical impact and biopsychosocial impact domains and summed scores range from 14 to 70 (14 points = zero impact, 15-28 points = limited impact, 29-42 points = moderate impact, 43-56 points = high impact, and 57-70 points = very high impact)[26,27].

FI and its impact on daily life was measured using the Revised Faecal Incontinence Score (RFIS)[28] and the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) questionnaire[29]. The RFIS is a questionnaire with five items related to FI and leakage altering a person’s lifestyle and two additional items related to FI associated with urge and undergarment soiling. Scores range from 0 to 20 (≤ 3 = none or very mild FI, 4-6 mild FI, 7-12 moderate FI, ≥ 13 severe FI). Scores for each item were summed and the mean was taken. The recall period for the RFIS was 4 wk. The FIQL is a 29-item questionnaire composed of four domains: Lifestyle, coping/behavior, depression/self-perception, and embarrassment. Scores range from 1 to 5 for each domain (no overall score), with a lower score indicating a worse HRQoL in that domain. The minimally important difference is 1.1-1.2 points per subscale[29,30]. The recall period for the FIQL was “the last month”.

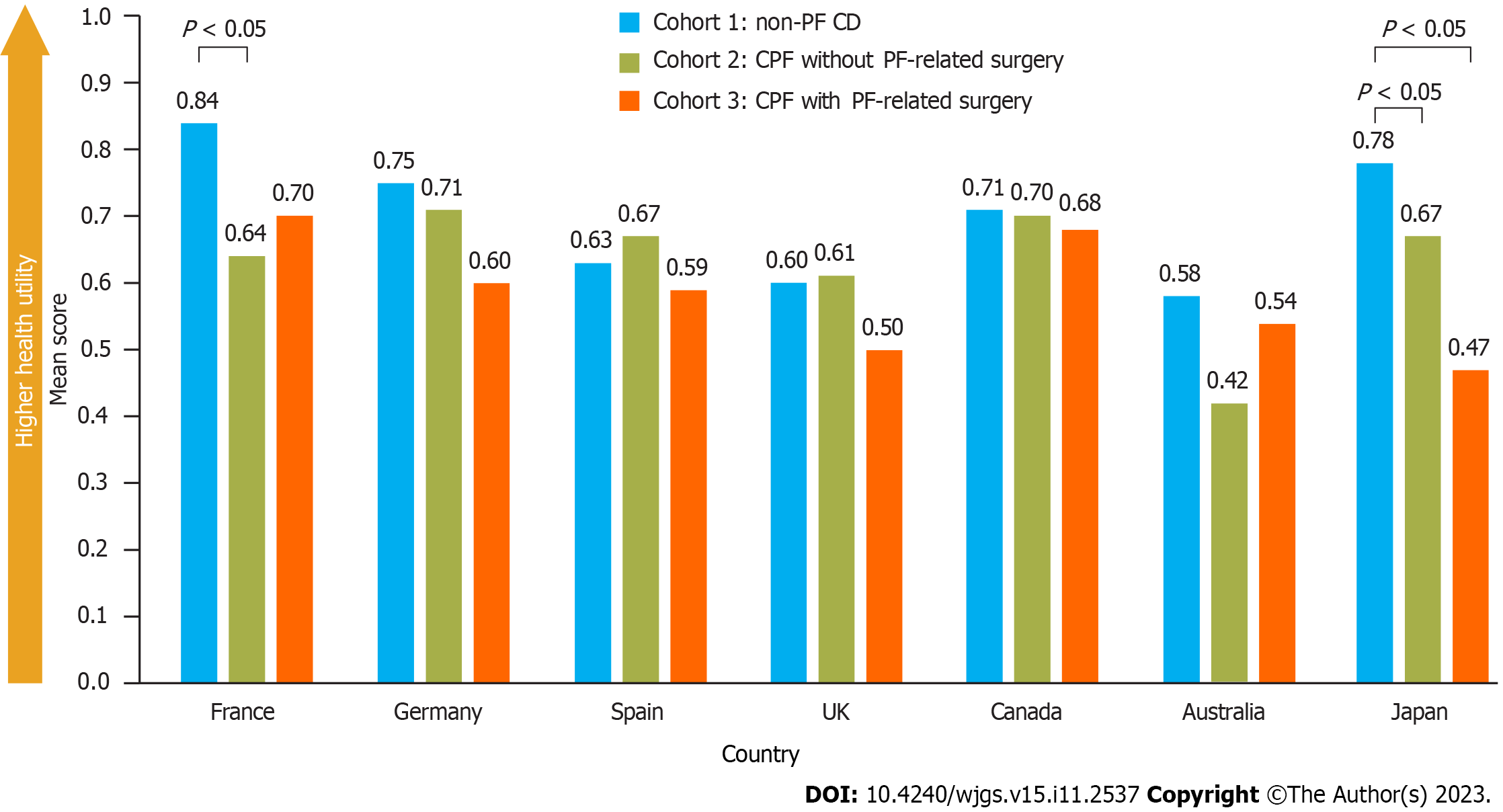

The EuroQol EQ-5D-5L questionnaire was utilized to assess the overall health status of the participating patients at the time of survey completion[31]. The questionnaire measures five dimensions of health including mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression and also includes a visual analog scale (VAS) to rate overall health. Each dimension has 5 levels: No problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and extreme problems. The total score ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher score indicating a better HRQoL. In countries where descriptions for only 3 levels of each dimension were published (EQ-5D-3L), a crosswalk score that maps EQ-5D-3L to EQ-5D-5L (3 vs 5 response options) was utilized.

Patient preferences for CPF treatment attributes were assessed through a DCE in patients with CPF. The DCE for this study included six treatment attributes across 2-4 levels (Table 1). It was estimated that a sample size of 260 patients would be sufficient to analyze each attribute, based on guidance by Yang et al[32]. Levels for each treatment attribute were derived from evidence in currently available literature[33-46] and used to develop hypothetical treatment profiles. The attributes included type of treatment, treatment success rate (overall success rate, potentially including radiologic healing rate), postoperative pain (pain following the treatment), rehabilitation time (time to resuming normal daily activities), recurrence rate (proportion of patients with a recurrence of CPF following treatment), and FI rate (proportion of patients with FI following treatment). In total, 10 choice sets were presented to each patient with two hypothetical treatments available for each choice. Patients had the option of selecting one hypothetical treatment profile as their most preferred treatment in each choice set, or to select neither.

| Attribute | Level | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Postoperative discomfort | Low | Medium | High | - |

| Fistula healing: Proportion of patients who have fistula closure/fistula healing and minimal fluid collection in the fistula after treatment | 48% | 55% | 60% | 95% |

| Fecal incontinence: Proportion of patients who experienced fecal incontinence after treatment | 0% | 16% | 20% | 34% |

| Recurrence: Proportion of patients with a return of symptoms related to anal fistula (discharge, pain, odor) after treatment | 15% | 25% | 35% | 60% |

| Rehabilitation time: Time taken to resume normal daily activities | Up to 1 wk | More than 1 wk, up to 4 wk | - | - |

| Invasiveness: Does the treatment involve cutting or puncturing of the skin? | Yes, involves cutting or puncturing and insertion of surgical instruments into the anal area | Yes, involves minimal cutting or puncturing and an injection of the treatment into the anal area | - | - |

Patients were asked to complete a list of questions to assess their treatment experience and CD experience. Questions included a wide range of demographic and clinical characteristics including diagnosis, treatment, and disease severity and complications, with medication and surgical experience being of particular interest. Interference with patients’ lives due to CD/CPF and specific disease attributes was assessed over the past 12 mo using a score ranging from 1 to 9 (a higher number indicating more significant interference with life). The impact of CPF on activities of daily living (ADL) over the past 12 mo was assessed using a score ranging from 1 to 7 (a higher number indicating more significant interference with ADL).

Patient satisfaction with currently available treatments for CPF was measured by assessing patient satisfaction with current PF treatments and PF treatment attributes, both scored 1-9 (low score indicating low satisfaction).

Patients were asked to rate their level of involvement in CD/PF treatment decision making as “not at all”, “slightly”, “moderately”, “very much”, or “I don’t feel the need to be involved”.

For all endpoints, data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, P values were calculated using t-tests and statistical significance was assessed at the 5% level. Bivariate comparisons were made between CPF cohorts (cohorts 2 and 3) and the non-PF cohort (cohort 1). Generalized linear models were used to statistically control for the effects of potential confounders in the data between patients with and without CPF.

The DCE data were analyzed using a hierarchical Bayesian model using the attribute levels as predictor variables and choice as the outcome variable. This model generated a mean relative attribute importance score for each attribute and a mean relative preference weight (RPW) for each level within the attributes tested.

This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and submitted to all applicable local Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Committees to ensure compliance with all ethical standards in each country.

In total, 929 patients were recruited; 620 patients had CD without PF (non-PF CD, cohort 1) and 309 patients had CPF (cohorts 2 and 3 combined; Figure 1). From each country, except Australia and Japan, 100 and 50 patients were recruited to cohort 1 and cohorts 2 and 3 combined, respectively. Australia and Japan both recruited 60 patients to cohort 1, and 29 and 30 patients to cohorts 2 and 3 combined, respectively.

The age distribution of patients was similar across the cohorts, with the exception that the non-PF CD cohort (cohort 1) had a greater proportion of patients aged 61-80 years than cohorts 2 and 3 (Table 2). A greater proportion of patients in the CPF cohorts were male compared with the non-PF CD cohort. Further patient demographics and characteristics used in the multivariable analyses to control for potential confounders in the patient-reported outcomes (comorbidities, CD flare-up status, employment status, and marital status) are provided in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1.

| Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | Cohorts 2 + 3 | |

| All non-PF CD (n = 620) | CPF no surgery (n = 174) | CPF with surgery (n = 135) | All CPF (n = 309) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 360 (58)a | 116 (67)b | 93 (69)b | 209 (68)c |

| Age, yr, n (%)1 | ||||

| 21-40 | 340 (55)a,d,e | 112 (64)c | 90 (67)c | 202 (65)c |

| 41-60 | 208 (34)b | 59 (34)b | 44 (33)b | 103 (33)b |

| 61-80 | 72 (12)a,d,e | 3 (2)c | 1 (1)c | 4 (1)c |

| CD flare-up status, n (%) | ||||

| Recent flare-up | 270 (44)a,e | 85 (49)e | 87 (64)c,d | 172 (56)c |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Asthma | 88 (14)b | 27 (16)b | 30 (22)b | 57 (18)b |

| Obesity | 87 (14)b | 31 (18)b | 22 (16)b | 53 (17)b |

| Cardiovascular disease | 33 (5)a,e | 13 (7)b | 17 (13)c | 30 (10)c |

| COPD | 17 (3)e | 4 (2)d | 11 (8)c,d | 15 (5)b |

| Cancer | 22 (4)b | 7 (4)b | 7 (5)b | 14 (5)b |

| Renal disease | 14 (2)b | 6 (3)b | 6 (4)b | 12 (4)b |

The questionnaire was generally well understood by respondents in the pre-test cognitive interviews and no major changes were required; however, in response to respondent feedback, minor modifications were made to the sentence structure and wording for further clarification.

HRQoL: Overall SIBDQ scores were lower (worse) for patients with CPF (cohorts 2 and 3) than those with non-PF CD (cohort 1) with significantly lower scores across all four domains of the SIBDQ (Figure 2A). Multivariable analyses to control for potential confounders (patient demographics and characteristics, identified via a model building approach) showed that SIBDQ scores after adjustment were still significantly lower for patients with CPF compared with those without CPF (other variables that were statistically significant are shown in Supplementary Table 2).

In patients with CPF, total (overall) QoLAF scores were comparable between cohorts 2 and 3. Biopsychosocial impact scores were similar, but for the physical impact domain, patients in cohort 3 (who had PF-related surgery) had a significantly higher (worse) score than those in cohort 2 (patients with no surgery, Figure 2B).

Overall, 47% of patients reported FI and completed the RFIS and FIQL questionnaires. A significantly lower proportion of patients with non-PF CD reported FI than those with CPF (40% in cohort 1 vs 59% and 59% in cohorts 2 and 3, respectively). Furthermore, mean RFIS scores were significantly higher (worse) in patients with CPF than in those without (Figure 3A). After using multivariable analyses to control for patient demographics (identified via a model building approach), RFIS scores were still significantly higher for patients with CPF compared with those without CPF (other variables that were statistically significant are shown in Supplementary Table 3).

Significantly lower (worse) FIQL scores were noted for patients with CPF and no PF-related surgery experience than for those with non-PF CD (cohort 2 vs cohort 1) across all domains except coping/behavior, whereas patients with PF-related surgery experience (cohort 3) reported significantly lower RFIS scores than cohort 1 only for the embarrassment domain (Figure 3B).

EQ-5D scores were not significantly different between cohorts, except in France where scores were significantly higher (better) for patients with non-PF CD (cohort 1) than those with CPF without PF-related surgery (cohort 2), and in Japan where scores were significantly higher for patients with non-PF CD than those with CPF, irrespective of PF-related surgery experience (Figure 4). After adjusting for confounding variables (identified via a model building approach), CPF was found to have a significantly negative impact on EQ-5D-5L scores in France, Germany, and Japan, but not in the other countries. EQ-5D VAS scores for overall health were not significantly different between cohorts across all countries (Supplementary Figure 1).

A higher proportion of patients with CPF had moderate or severe disease, CD-related complications, and had experienced reported FI, compared with patients with non-PF CD (Table 3). CD-related complications included fatigue, abdominal pain/cramping, gastrointestinal pain, pain/difficulty with bowel movements, and pain when sitting (Supplementary Table 4). At the time of enrollment, a higher proportion of patients with CPF were currently taking or had previously taken CD-related medication than those with non-PF CD (98% vs 94%, respectively, P < 0.05; Table 4). Also, a higher proportion of patients with CPF had CD-related surgeries than those without CPF (cohort 1) and the proportion was greatest in those who had PF-related surgery (cohort 3). This likely accounts for the higher proportion of patients in cohort 3 with surgical failures compared with cohorts 1 and 2.

| Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | Cohorts 2 + 3 | |

| All non-PF CD (n = 620) | CPF no surgery (n = 174) | CPF with surgery (n = 135) | All CPF (n = 309) | |

| Ever experienced fecal incontinence, n (%) | 251 (40)a,b,c | 103 (59)d | 80 (59)d | 183 (59)d |

| More than 5 CD complications, n (%) | 266 (43)a,b,c | 135 (78)d | 111 (82)d | 246 (80)d |

| PF experience | ||||

| Number of unique PFs (mean ± SD) | NA | 2.3 (1.4)b | 3.0 (3.0)a | NA |

| Experience with PF recurrence/persistence, n (%) | NA | 84 (48)e | 80 (59)e | NA |

| CD severity (physician classified) at diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Mild | 187 (30)a,b,c | 24 (14)d | 23 (17)d | 47 (15)d |

| Moderate | 298 (48)a,b,c | 123 (71)b,d | 78 (58)a,d | 201 (65)d |

| Severe | 86 (14)b | 22 (13)b | 31 (23)a,d | 53 (17)e |

| Not sure | 49 (8)a,b,c | 5 (3)d | 3 (2)d | 8 (3)d |

| Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | Cohorts 2 + 3 | |

| All non-PF CD (n = 620) | CPF no surgery (n = 174) | CPF with surgery (n = 135) | All CPF (n = 309) | |

| CD-related medication experience, n (%) | ||||

| Currently taking | 429 (69)a,b,c | 147 (84)d | 108 (80)d | 255 (83)d |

| Previously taken | 155 (25)a,b,c | 27 (16)d | 22 (16)d | 49 (16)d |

| Never taken | 36 (6)a,c | 0b,d | 5 (4)a | 5 (2)d |

| CD-related surgical experience | ||||

| Frequency of surgical experience ever, n (%) | 190 (31)a,b,c | 78 (45)b,d | 119 (88)a,d | 197 (64)d |

| Number of surgeries in the past 12 mo (mean ± SD) | 1.5 (0.9)b,c | 1.8 (1.1)b | 2.2 (1.3)a,d | 2.0 (1.3)d |

| Number of surgeries in the past 12 mo (median) | 1e | 1e | 2e | 2e |

| Frequency of surgical failure ever, n (%) | 52 (27)b,c | 22 (28)b | 55 (46)a,d | 77 (39)d |

| Number of failed surgeries ever (mean ± SD) | 1.7 (2.1)e | 2.2 (1.6)e | 1.9 (1.8)e | 2.0 (1.7)e |

| Number of failed surgeries ever (median) | 1e | 2e | 1e | 1e |

| PF-related surgical care | ||||

| PF-related procedure or surgery frequency (mean ± SD) | NA | NA | 5.6 (3.5)e | NA |

| One PF-related procedure or surgery | NA | NA | 9 (7)e | NA |

| Two PF-related procedures or surgeries | NA | NA | 21 (16)e | NA |

| Three or more PF-related procedures or surgeries | NA | NA | 105 (78)e | NA |

| Failure of PF-related procedure or surgical care (at any time) ever, n (%) | ||||

| One failed PF-related procedure or surgery | NA | NA | 35 (26)e | NA |

| Two or more failed PF-related procedure or surgery | NA | NA | 19 (14)e | NA |

In patients with CPF and PF-related surgery experience (cohort 3), 78% had three or more such procedures or surgeries related to their PF and 87% of patients experienced ≥ 1 complication after surgery or seton placement. The most frequent complications after PF-related surgery or seton placement included fever/infection, worsening of pain/swelling around the anus, and worsening of bloody or foul-smelling discharge from an opening around the anus (Supplementary Table 5).

The mean RPW provided an estimation of the strength of preference for each level within the attributes tested (higher RPWs indicated a higher preference and lower RPWs indicated a lower preference). Patient preferences were driven by levels of postoperative discomfort [mean RPW (standard error, SE) of 0.20 (0.03) for low levels of discomfort vs -0.28 (0.03) for high levels of discomfort]. Patients also preferred treatments that result in high rates of fistula healing with minimal fluid collection [mean RPW (SE) of 0.24 (0.04) for treatments with approximately 95% fistula healing rate vs -0.09 (0.04) for treatments with approximately 48% or approximately 55% fistula healing rate]. Levels of FI after treatment were also a driving factor in patient treatment preferences [mean RPW (SE) of 0.13 (0.04) for no FI vs -0.10 (0.04) for approximately 34% rate of FI after treatment]. Overall, of the tested attributes, postoperative discomfort and fistula healing rate were the most important attributes influencing patient choice in the treatment of CPF (Figure 5).

Overall impact of CD/CPF on life: Disease impact (in terms of interference with a patient’s life) was significantly greater in patients with CPF than those without, with worse impact scores for all cohorts during flare-up (Supplemen

Impact of CD/CPF disease attributes on HRQoL: Patients with CPF experienced a significantly higher impact of disease attributes on their HRQoL than patients with non-PF CD (Supplementary Table 7). The most impactful disease attributes were diarrhea (cohorts 1 and 2) and anorectal stricture (patients with PF-related surgery, cohort 3).

Impact of CD/CPF disease attributes on activities of daily living: Overall, significantly higher scores (higher impact) across all activities were recorded for patients with CPF vs those without. For patients without CPF, the most affected activities were exercising [mean ± SD 4.0 (1.6)], being satisfied with life [4.0 (1.7)], and ability to go to school [including any level of education; 4.0 (1.6)]. For patients with CPF, the most affected activities were exercising [4.6 (1.5)], being satisfied with life [4.6 (1.5)], and ability to work outside home [4.6 (1.5)].

Treatment satisfaction: Mean satisfaction scores were moderate (6.2-6.9) for all PF treatment options and similar in both cohorts of patients with CPF; however, patients with PF-related surgery (cohort 3) had significantly less satisfaction with long-term seton placement than those without PF-related surgery (cohort 2): 6.2 vs 6.7, respectively; P < 0.05 (Table 5).

| Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | |

| CPF no surgery (n = 174) | CPF with surgery (n = 135) | |

| Satisfaction with PF treatments (on a scale of 1-9), mean ± SD, % rated ≥ 7 | ||

| Medication | 6.5 (1.4), 57a | 6.4 (1.5), 50a |

| Long-term seton placement | 6.7 (1.5), 57b | 6.2 (1.7), 47c |

| Endorectal/anal advancement flap | 6.2 (1.7), 52a | 6.3 (1.7), 52a |

| Fibrin glue | 6.4 (1.9), 61a | 6.2 (1.6), 45a |

| Anal fistula plug | 6.6 (1.8), 66a | 6.5 (1.6), 56a |

| Fistulectomy/fistulotomy | 6.9 (1.6), 68a | 6.3 (1.9), 50a |

| LIFT (ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract) | 6.7 (1.5), 65a | 6.2 (1.7), 46a |

| Satisfaction with PF treatment attributes (on a scale of 1-9), mean ± SD, % rated ≥ 7 | ||

| Aids in closure of external opening of the fistulas | 6.4 (1.5), 48a | 6.5 (1.6), 55a |

| Reduction or no drainage | 6.4 (1.6), 54a | 6.4 (1.6), 51a |

| Time required for symptom improvement | 6.3 (1.6), 54a | 6.3 (1.7), 50a |

| Time required for rehabilitation | 6.2 (1.7), 51a | 6.2 (1.8), 52a |

| Length of duration before symptom(s) recur | 6.3 (1.7), 52a | 6.3 (1.8), 52a |

| Has minimal side effects (local pain, redness, itchiness) | 6.2 (1.9), 54a | 6.3 (1.8), 53a |

| Minimal risk of fecal incontinence | 6.3 (1.7), 51a | 6.4 (1.7), 53a |

| Not requiring a long-term seton placement | 6.4 (1.7), 52a | 6.6 (1.7), 59a |

| Less invasive nature of treatment (not requiring incision) | 6.4 (1.7), 56a | 6.3 (1.8), 48a |

Involvement in CD/PF treatment decision making: The majority of patients across all cohorts in all countries were either moderately or very much involved in their CD/CPF treatment decision making (78%-81%); 1%-3% indicated no involvement and 1%-2% indicated they did not feel the need to be involved.

Patients with CPF are a subset of patients with CD that experience a more complex clinical disease course and may require unique treatment considerations. This large multi-country study used validated patient-reported outcome measures and general questionnaires to assess the burden of illness for patients with CPF compared with patients with non-PF CD. For patients with CPF, these outcomes were also compared between those who had PF-related surgery and those who did not. A DCE was also conducted to assess the treatment preferences of patients with CPF.

As shown in this study, patients with CPF have an incrementally higher symptom burden due to both CD and PF than patients with non-PF CD. Severity of CD is higher in patients with CPF than in those with non-PF CD, with the greatest severity observed in those with PF-related surgery: A higher proportion of patients with CPF experience FI and CD-related complications such as fatigue, abdominal and gastrointestinal pain, and difficulty with bowel movements. In addition, patients with CPF can experience symptoms directly related to their fistulas such as purulent discharge, perianal pain, and FI. The greater CD severity in patients with CPF is reflected in the higher proportion of patients with CPF who received CD-related medications and surgery than in patients with non-PF CD. Furthermore, patients with CPF were shown to have a significant impact on their overall HRQoL. This finding is in line with a 2023 study by Spinelli et al[47], where patients with CPF reported a greater impact on overall quality of life, well-being, relationships, social life, and work life than those with CD without CPF[47]. In the current study, there was no significant difference in reported HRQoL between patients who had PF-related surgery and those who had not. Patients with CPF reported a greater impact of CD/CPF disease attributes on HRQoL, irrespective of PF-related surgery, than patients with non-PF CD.

A high proportion of patients in this study reported being actively involved in their treatment decision making, and for patients with CPF, satisfaction with PF treatment options was only moderate, regardless of whether they had experienced surgical intervention or not. The DCE performed in this study showed that patients with CPF prioritize postoperative discomfort and healing rate as the primary attributes when selecting a hypothetical treatment choice. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time a DCE has been performed in this patient population, offering a unique perspective on patient preferences for CPF treatments.

The key findings from this study are in keeping with the core outcomes identified by Sahnan et al[48] and are comparable with the findings of a recent study in a similar patient population conducted in the United States[48,49]. Further research on the potential impact of age, sex, and disease severity on patients’ treatment preferences could support healthcare professionals in the clinical management and treatment decisions for CPF.

There are some limitations that should be acknowledged with studies of this type. Patient responses to questionnaires can be subject to recall, selection, and/or social desirability bias, and inaccuracies owing to self-reported diagnosis and the use of complex medical terminology. The risks of such effects were partly mitigated by limiting the recall period to 12 mo or less and using pre-test telephone interviews and a web-enabled questionnaire. There was no validation sample of patients in relation to self-reported diagnosis (for cohort categorization) because it was assumed that patients would know whether or not they have CPF. Finally, the sample population may not have been representative of the wider population of patients with CD, and any country/regional differences need to be further evaluated.

This is the largest known observational study to quantify the burden of illness associated with CPF across multiple countries utilizing a comprehensive set of outcomes including symptom burden and impacts, and treatment experience, satisfaction, and preferences. This study confirmed that the burden of illness for patients with CD is significantly higher for those with CPF than those without. CPF management should aim to reduce the overall disease burden, including treatment-related burden or complications, such as FI, to improve HRQoL for these patients.

The burden of illness in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) is perceived to be greater in those with perianal fistulas vs those without. However, there is limited literature directly comparing the symptom burden, impact on quality of life and the treatment experiences, and preferences in patients with CD with and without perianal fistula.

A more in-depth understanding of disease burden and treatment preferences of patients with Crohn’s perianal fistula will be key in raising disease awareness and helping healthcare professionals with the clinical management of these patients.

To examine the symptom burden, health-related quality of life, and treatment experiences, satisfaction, and preferences for patients with CD with and without perianal fistula, and to further assess the incremental burden of these measures for patients who have and have not received perianal fistula-related surgery.

A large cross-sectional, multi-country observational study was conducted via a pre-tested web-enabled questionnaire in seven countries. Data on disease insights and experiences were collected, and validated patient-reported outcome measures were used to assess the disease-specific health-related quality of life, fecal incontinence, and general health status of participating patients. All participating patients had CD and comparisons were made between patients without perianal fistula and those with perianal fistula (with further comparisons between those with and without perianal fistula-related surgery). Patient preferences for perianal fistula treatments were also assessed using a discrete choice experiment.

This study demonstrated that symptom burden, severity of disease, CD-related medication/surgical interventions, and impact on health-related quality of life in patients with CD are significantly higher for those with perianal fistula than those without. Patients with Crohn’s perianal fistula were found to prioritize postoperative discomfort and healing rate as the primary attributes when selecting a hypothetical surgical treatment choice.

For patients with CD, the symptom and treatment burden and impact on health-related quality of life are significantly higher for those with perianal fistula than those without. Future Crohn’s perianal fistula management should aim to reduce the treatment-related burden or complications, in order to improve health-related quality of life for these patients.

The patient satisfaction rates and surgical treatment preferences highlighted in this study should be considered by healthcare professionals when making decisions regarding the clinical management of patients with Crohn’s perianal fistula.

The authors would like to thank Emily Sharpe, PhD, for her contributions to this study; Sally McTaggart, PhD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK for the Medical writing support; and Takeda Pharmaceuticals for supporting this study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Choi YS, South Korea; Zhou W, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46-54.e42; quiz e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3789] [Cited by in RCA: 3526] [Article Influence: 271.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Freeman HJ. Natural history and long-term clinical course of Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Lightner AL, Ashburn JH, Brar MS, Carvello M, Chandrasinghe P, van Overstraeten AB, Fleshner PR, Gallo G, Kotze PG, Holubar SD, Reza LM, Spinelli A, Strong SA, Tozer PJ, Truong A, Warusavitarne J, Yamamoto T, Zaghiyan K. Fistulizing Crohn's disease. Curr Probl Surg. 2020;57:100808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Panes J, Reinisch W, Rupniewska E, Khan S, Forns J, Khalid JM, Bojic D, Patel H. Burden and outcomes for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4821-4834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kamal N, Motwani K, Wellington J, Wong U, Cross RK. Fecal Incontinence in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohns Colitis 360. 2021;3:otab013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Norton C, Dibley LB, Bassett P. Faecal incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease: associations and effect on quality of life. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e302-e311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Petryszyn PW, Paradowski L. Stool patterns and symptoms of disordered anorectal function in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27:813-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Steinhart AH, Panaccione R, Targownik L, Bressler B, Khanna R, Marshall JK, Afif W, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, Borgaonkar M, Chauhan U, Halloran B, Jones J, Kennedy E, Leontiadis GI, Loftus EV Jr, Meddings J, Moayyedi P, Murthy S, Plamondon S, Rosenfeld G, Schwartz D, Seow CH, Williams C. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Medical Management of Perianal Fistulizing Crohn's Disease: The Toronto Consensus. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fan Y, Delgado-Aros S, Valdecantos WC, Janak JC, Moore PC, Crabtree MM, Stidham RW. Characteristics of Patients with Crohn's Disease With or Without Perianal Fistulae in the CorEvitas Inflammatory Bowel Disease Registry. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:214-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gold SL, Cohen-Mekelburg S, Schneider Y, Steinlauf A. Perianal Fistulas in Patients With Crohn's Disease, Part 1: Current Medical Management. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14:470-481. [PubMed] |

| 11. | de Groof EJ, Cabral VN, Buskens CJ, Morton DG, Hahnloser D, Bemelman WA; research committee of the European Society of Coloproctology. Systematic review of evidence and consensus on perianal fistula: an analysis of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:O119-O134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 927] [Article Influence: 132.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, Magro Dias FJ, Rogler G, Lakatos PL, Adamina M, Ardizzone S, Buskens CJ, Sebastian S, Laureti S, Sampietro GM, Vucelic B, van der Woude CJ, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Maaser C, Portela F, Vavricka SR, Gomollón F; ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical Management and Special Situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:135-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 66.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, Spinelli A, Warusavitarne J, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, Doherty G, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Fiorino G, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gisbert JP, Gomollon F, González Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Kucharzik T, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Stassen L, Torres J, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Zmora O. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Surgical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:155-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 73.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, Adamina M, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gomollon F, González-Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Spinelli A, Stassen L, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Warusavitarne J, Zmora O, Fiorino G. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:4-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 991] [Cited by in RCA: 902] [Article Influence: 180.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Chen G, Pedarla V, Null KD, Cazzetta SE, Khan QR, Schwartz DA. Health Care Costs and Resource Utilization Among Patients With Crohn's Disease With and Without Perianal Fistula. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:870-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Adegbola SO, Dibley L, Sahnan K, Wade T, Verjee A, Sawyer R, Mannick S, McCluskey D, Yassin N, Phillips RKS, Tozer PJ, Norton C, Hart AL. Burden of disease and adaptation to life in patients with Crohn's perianal fistula: a qualitative exploration. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Molendijk I, Nuij VJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, van der Woude CJ. Disappointing durable remission rates in complex Crohn's disease fistula. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2022-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ryan M, Bate A, Eastmond CJ, Ludbrook A. Use of discrete choice experiments to elicit preferences. Qual Health Care. 2001;10 Suppl 1:i55-i60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kjaer T. A review of the discrete choice experiment-with emphasis on its application in health care: Syddansk Universitet Denmark, 2005. [cited 10 October 2023]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265363271_A_review_of_the_Discrete_Choice_Experiment-with_Emphasis_on_Its_Application_in_Health_Care. |

| 21. | Wang Y, Wang Z, Li X, Pang X, Wang S. Application of Discrete Choice Experiment in Health Care: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front Public Health. 2021;9:673698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Athavale A, Gooch K, Walker D, Suh M, Scaife J, Haber A, Hadker N, Dmochowski R. A patient-reported, non-interventional, cross-sectional discrete choice experiment to determine treatment attribute preferences in treatment-naïve overactive bladder patients in the US. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2139-2152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dubow J, Avidan AY, Corser B, Athavale A, Seiden D, Kushida C. Preferences for Attributes of Sodium Oxybate Treatment: A Discrete Choice Experiment in Patients with Narcolepsy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:937-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kleij KS, Tangermann U, Amelung VE, Krauth C. Patients' preferences for primary health care - a systematic literature review of discrete choice experiments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn's Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-1578. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Ferrer-Márquez M, Espínola-Cortés N, Reina-Duarte Á, Granero-Molina J, Fernández-Sola C, Hernández-Padilla JM. Analysis and description of disease-specific quality of life in patients with anal fistula. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 2018;96:213-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ferrer-Márquez M, Espínola-Cortés N, Reina-Duarte A, Granero-Molina J, Fernández-Sola C, Hernández-Padilla JM. Design and Psychometric Evaluation of the Quality of Life in Patients With Anal Fistula Questionnaire. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:1083-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sansoni J, Hawthorne G, Fleming G, Marosszeky N. The revised faecal incontinence scale: a clinical validation of a new, short measure for assessment and outcomes evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:652-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantonis C, Thorson AG, Wexner SD, Bliss D, Lowry AC. Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:9-16; discussion 16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bols EM, Hendriks HJ, Berghmans LC, Baeten CG, de Bie RA. Responsiveness and interpretability of incontinence severity scores and FIQL in patients with fecal incontinence: a secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:469-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rencz F, Lakatos PL, Gulácsi L, Brodszky V, Kürti Z, Lovas S, Banai J, Herszényi L, Cserni T, Molnár T, Péntek M, Palatka K. Validity of the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-3L in patients with Crohn's disease. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:141-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yang JC, Johnson FR, Kilambi V, Mohamed AF. Sample size and utility-difference precision in discrete-choice experiments: A meta-simulation approach. J Choice Model. 2015;16: 50-57. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart DC, Dignass A, Nachury M, Ferrante M, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Grimaud JC, de la Portilla F, Goldin E, Richard MP, Leselbaum A, Danese S; ADMIRE CD Study Group Collaborators. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1281-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 730] [Article Influence: 81.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB; American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Gold SL, Cohen-Mekelburg S, Schneider Y, Steinlauf A. Perianal Fistulas in Patients With Crohn's Disease, Part 2: Surgical, Endoscopic, and Future Therapies. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14:521-528. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Stellingwerf ME, van Praag EM, Tozer PJ, Bemelman WA, Buskens CJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endorectal advancement flap and ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for cryptoglandular and Crohn's high perianal fistulas. BJS Open. 2019;3:231-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | van Praag EM, Stellingwerf ME, van der Bilt JDW, Bemelman WA, Gecse KB, Buskens CJ. Ligation of the Intersphincteric Fistula Tract and Endorectal Advancement Flap for High Perianal Fistulas in Crohn's Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:757-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart DC, Dignass A, Nachury M, Ferrante M, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Grimaud JC, de la Portilla F, Goldin E, Richard MP, Diez MC, Tagarro I, Leselbaum A, Danese S; ADMIRE CD Study Group Collaborators. Long-term Efficacy and Safety of Stem Cell Therapy (Cx601) for Complex Perianal Fistulas in Patients With Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1334-1342.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | van Koperen PJ, Safiruddin F, Bemelman WA, Slors JF. Outcome of surgical treatment for fistula in ano in Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2009;96:675-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bakhtawar N, Usman M. Factors Increasing the Risk of Recurrence in Fistula-in-ano. Cureus. 2019;11:e4200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Becker HD, Starlinger M. Clinical course after transanal advancement flap repair of perianal fistula in patients with Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1995;82:603-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, Da Silva G, Efron J, Weiss EG, Vernava AM 3rd, Nogueras JJ. Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1616-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Vander Mijnsbrugge GJH, Felt-Bersma RJF, Ho DKF, Molenaar CBH. Perianal fistulas and the lift procedure: results, predictive factors for success, and long-term results with subsequent treatment. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:639-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Visscher AP, Schuur D, Roos R, Van der Mijnsbrugge GJ, Meijerink WJ, Felt-Bersma RJ. Long-term follow-up after surgery for simple and complex cryptoglandular fistulas: fecal incontinence and impact on quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Göttgens KWA, Wasowicz DK, Stijns J, Zimmerman D. Ligation of the Intersphincteric Fistula Tract for High Transsphincteric Fistula Yields Moderate Results at Best: Is the Tide Turning? Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:1231-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Schiano di Visconte M, Bellio G. Comparison of porcine collagen paste injection and rectal advancement flap for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistulas: a 2-year follow-up study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1723-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Spinelli A, Yanai H, Girardi P, Milicevic S, Carvello M, Maroli A, Avedano L. The Impact of Crohn’s Perianal Fistula on Quality of Life: Results of an International Patient Survey. Crohn's Colitis. 2023;5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sahnan K, Tozer PJ, Adegbola SO, Lee MJ, Heywood N, McNair AGK, Hind D, Yassin N, Lobo AJ, Brown SR, Sebastian S, Phillips RKS, Lung PFC, Faiz OD, Crook K, Blackwell S, Verjee A, Hart AL, Fearnhead NS; ENiGMA collaborators. Developing a core outcome set for fistulising perianal Crohn's disease. Gut. 2019;68:226-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Athavale A, Edelblut J, Chen M, Cazzetta SE, Nazarey PP, Fan T, Hadker N, Jiang J. S1022 Treatment Preferences in Crohn’s Disease Perianal Fistula: Patient Perspectives. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology|ACG 2022; 117(10S). |