Published online Oct 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i10.2362

Peer-review started: July 4, 2023

First decision: August 4, 2023

Revised: August 18, 2023

Accepted: August 31, 2023

Article in press: August 31, 2023

Published online: October 27, 2023

Processing time: 114 Days and 22.3 Hours

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive mucocutaneous ulcers (MCUs) are an un

The patient presented with an incidental finding of a small bowel tumor during computed tomography (CT) examination performed for hematuria. The CT scan showed irregular thickening of the distal ileum, which was suggestive of a malignant small bowel tumor. An exploratory laparotomy revealed an 8-cm mass in the distal ileum; thus, a segment of the small intestine, including the mass, was resected. Histopathological analysis revealed an ulceroinfiltrative mass-like lesion with luminal narrowing, marked inflammatory cell infiltration, and large atypical lymphoid cells (positive for EBV-encoded small RNA). A final diagnosis of an EBV-MCU was established. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 7. The patient remained recurrence-free until 12 mo after surgery.

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges for EBV-MCUs and emphasizes the importance of comprehensive evaluation and accurate histopathological analysis.

Core Tip: We report a case that highlights the diagnostic challenges of distinguishing an Epstein–Barr virus-mucocutaneous ulcer from a small bowel adenocarcinoma in a 69-year-old woman. It emphasizes the importance of performing comprehensive evaluation and accurate histopathological analysis to guide appropriate management. Awareness of this rare entity is crucial for its timely diagnosis and prevention of unnecessary invasive procedures.

- Citation: Song JH, Choi JE, Kim JS. Mucocutaneous ulcer positive for Epstein–Barr virus, misdiagnosed as a small bowel adenocarcinoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(10): 2362-2366

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i10/2362.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i10.2362

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive mucocutaneous ulcer (MCU) is an uncommon disorder characterized by ulcerative lesions in the skin, oral cavity, or gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Previous reports have revealed that EBV-MCU is primarily associated with drug-induced immunosuppression or age-related immunosenescence[1]. Most cases of EBV-MCU respond well to conservative treatment, such as reduction of immunosuppressive drugs; surgical resection is required in only a minority of cases[2].

However, EBV-MCU diagnosis is challenging due to the nonspecific nature of the ulcerative lesions, which makes it difficult to distinguish from other tumorous conditions (such as small bowel adenocarcinoma). Small bowel adenocarcinoma is rare, accounting for ~3% of all GI cancers[3]. The rarity of cases and the presence of nonspecific symptoms often pose a challenge to achieving early and accurate diagnosis[4]. The complex etiology and histopathological heterogeneity of small bowel adenocarcinoma further contribute to the difficulty in establishing a definitive diagnosis[5].

A diagnostic challenge arises when EBV-MCU occurs in the GI tract, thereby mimicking small bowel adenocarcinoma. Potential misdiagnosis may subject patients to unnecessary invasive procedures or inappropriate treatment. Thus, both conditions must be differentiated to ensure appropriate management. In this case report, we present a rare case of surgically diagnosed and treated EBV-MCU that was initially misdiagnosed as small bowel adenocarcinoma. By highlighting this case, we aim to raise awareness of the importance of accurately distinguishing between these two conditions to ensure effective management and prevent potential harm to the patients.

A 69-year-old woman presented with hematuria during routine screening.

Computed tomography (CT) urography was performed at the Department of Nephrology. Incidentally, a small bowel tumor was detected on the CT scan, prompting a referral to our department.

The patient had no other underlying diseases, except for hypertension, and did not complain of GI symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain). There was no history of previous pulmonary tuberculosis.

The patient had no relevant family history.

A physical examination revealed normoactive bowel sounds, no abdominal distention, and no prominent tenderness. The vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 141/86 mmHg; pulse rate, 70 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and body temperature, 36.2°C.

Laboratory tests indicated anemia, with the following findings: hemoglobin, 9.2 g/dL (reference: 12–16 g/dL); mean corpuscular volume, 87.8 fL (reference: 80–100 fL); mean corpuscular hemoglobin, 29.8 pg (reference: 26–38 pg); serum iron, 82 μg/dL (reference: 29–164 μg/dL); ferritin, 116 ng/mL (reference: 13–150 ng/mL); and unsaturated iron binding capacity, 135 μg/dL (reference: 191–269 μg/dL). Tumor markers, namely carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, were within their normal limits (0.697 ng/mL and 3.8 U/mL, respectively). No other abnormalities were noted.

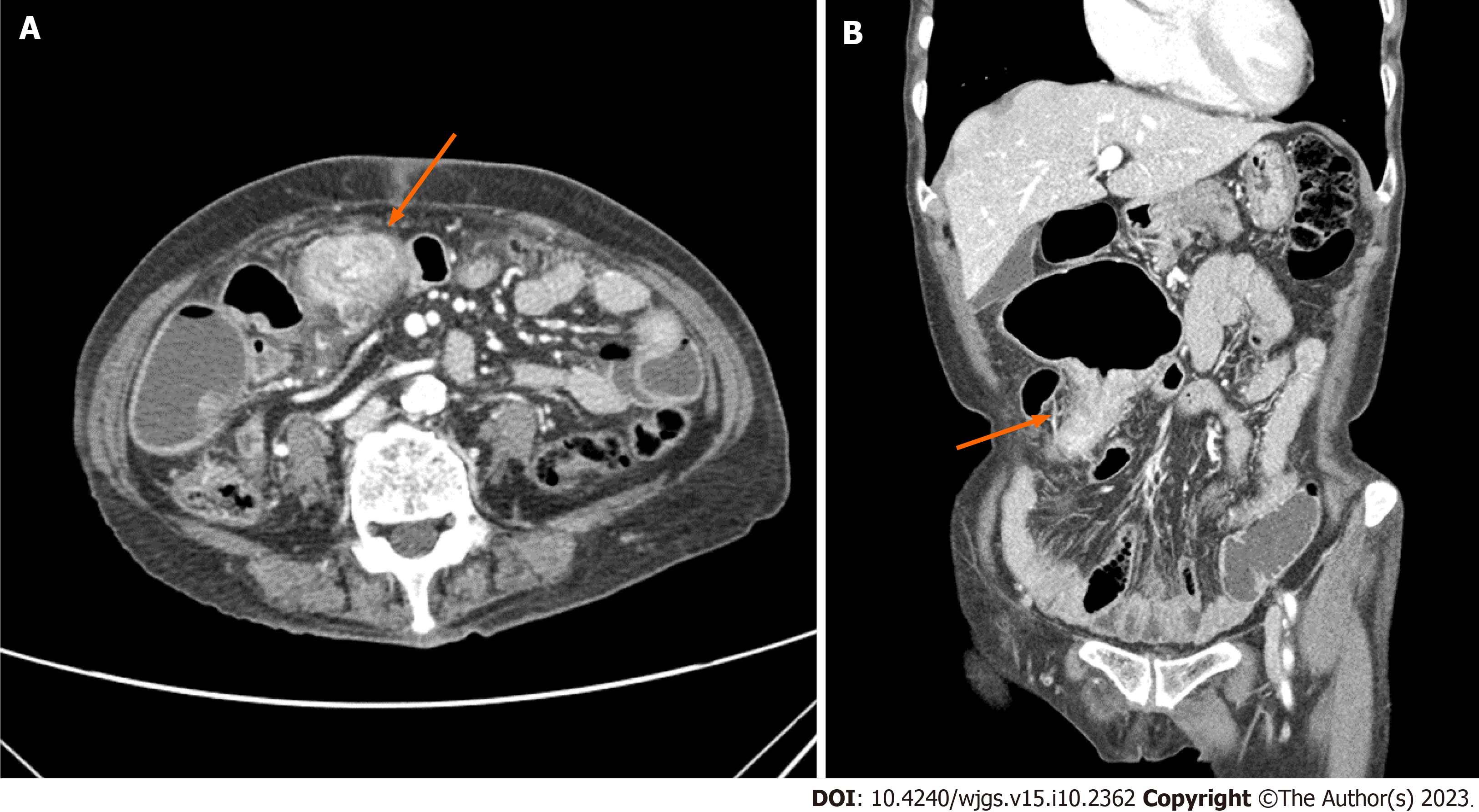

A CT scan revealed irregular thickening of the distal ileum, which caused proximal small bowel dilatation, and several enlarged lymph nodes in the mesentery and preaortic area (Figure 1). These findings suggested the presence of a malignant small bowel tumor with lymph node metastasis. No findings indicative of GI bleeding were observed during an endoscopic evaluation.

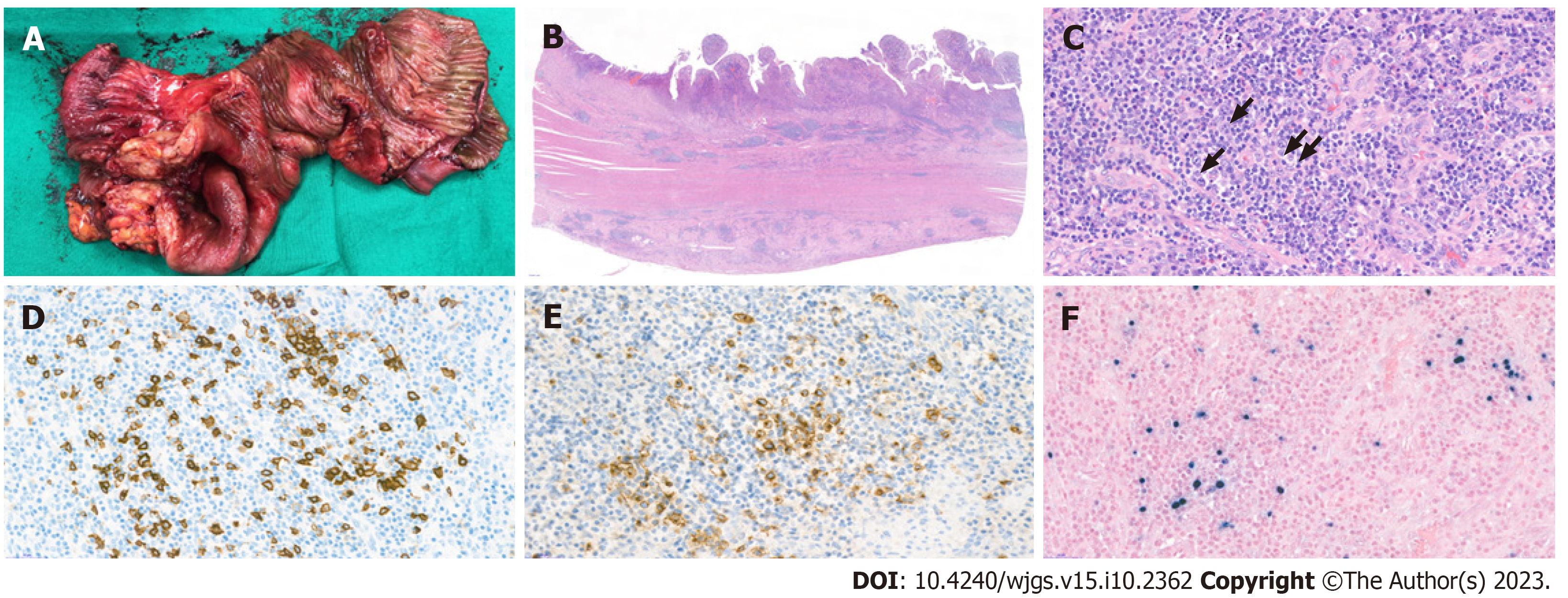

The resected specimen was analyzed histopathologically. Grossly, the specimen showed a single ulcerative lesion with luminal obstruction, and the adjacent mucosa was edematous (Figure 2A). Microscopically, the mucosal surface showed ulceration with the formation of granulation tissue formation and marked inflammatory cell infiltration in all the layers of the colon wall; the inflammatory cells comprised a variable number of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils, as well as a small number of large atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 2B and 2C). Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that these lymphoid cells were B cells with CD20 and CD30 positivity (Figure 2D and 2E). In situ hybridization further revealed that these cells were also positive for EBV-encoded small RNA (Figure 2F). No evidence of definite malignancy or tuberculosis was noted. Thus, a final diagnosis of EBV-MCU was established.

An exploratory laparotomy was performed for definitive diagnosis and treatment. During surgery, a mass of ~8 cm was identified at the distal ileum, 30 cm from the ileocecal valve. A 50-cm segment of the small intestine (including the mass) was resected, and D2 lymphadenectomy was performed. Anastomosis was performed using the hand-sewn method. The resected specimen showed a 7 cm × 4.5 cm ulceroinfiltrative mass-like lesion with luminal narrowing.

The patient had an uneventful postoperative course, and was discharged on postoperative day 7. The patient remained recurrence-free until 12 mo after surgery.

EBV-MCU was first identified as a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder in 2010 by Dojcinov et al[1]. They reported a series of 26 EBV-MCU cases involving the oropharyngeal mucosa, skin, and GI tract; these were associated with drug-induced immunosuppression or age-related immunosenescence. Since then, several cases have been reported, and the 2016 World Health Organization classification recognized the condition as a newly identified entity[6]. Based on the absence of immunosuppression in the present case, the patient was considered to have developed EBV-MCU due to age-related immunosenescence.

A review by Sinit et al[2] discussed the first 100 reported cases of EBV-MCU, which revealed that the most commonly affected site was the oropharyngeal mucosa, followed by the GI tract and skin. The treatments administered included reduction of immunosuppressive drugs, systemic therapy, radiotherapy, and surgical resection in 50, 22, 10, and six cases, respectively. Only one of the six surgically treated cases involved the GI tract[7]. Only two out of the 100 small intestinal cases did not require surgical treatment. Conversely, the present case involved surgical resection of a tumorous lesion in the small intestine, which was initially misdiagnosed as small bowel adenocarcinoma but subsequently confirmed to be EBV-MCU through histopathological analysis.

Ishikawa et al[8] summarized 30 reported cases of EBV-MCUs involving the GI tract. The large intestine was the most commonly affected site, while the small intestine was only involved in three cases. Surgical treatment was undertaken in 10 of the 30 cases. Our case, however, presented with EBV-MCU-induced intestinal obstruction that required surgery; this is consistent with the findings reported by Morita et al[7]. Nonetheless, preoperative endoscopic access was challenging due to the location of the lesion in the small intestine. To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first reported instance of an EBV-MCU causing small intestinal obstruction and necessitating surgical treatment.

For EBV-MCU, the pivotal aspect in clinical practice is its accurate differentiation from other related conditions, such as small bowel adenocarcinoma or intestinal tuberculosis. This differentiation hinges upon comprehensive assessment of the clinical manifestations and imaging features, which enables precise diagnosis and development of tailored treatment strategies. EBV-MCUs frequently emerge in immunocompromised patients, especially those receiving immunosuppressive therapy or undergoing age-related immunosenescence[8]. A reduction in immunosuppressant dose often leads to an improvement in the lesions, which offers a diagnostic clue for EBV-MCU. EBV-MCUs often present as ulcerative lesions with infiltrative margins in mucosal areas on imaging studies.

For small bowel adenocarcinoma, clinical manifestations may include nonspecific signs, such as weight loss, anemia, and abdominal discomfort[9]; conversely, common imaging findings include nodular or irregular thickening of the small bowel wall, which is often accompanied by luminal narrowing. In case of intestinal tuberculosis, patients may present with constitutional symptoms, such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss; imaging findings may include thickened intestinal walls or nodules, mostly in the ileocecal area[10].

While these clinical manifestations and imaging features could help differentiate EBV-MCU from small bowel adenocarcinoma or intestinal tuberculosis, there may be cases with overlapping characteristics. Thus, diagnosis of GI-tract-associated EBV-MCU remains challenging without surgery, and accurate diagnosis requires a combination of clinical assessment, imaging studies, and histopathological analysis[7,8,11].

Although EBV-MCUs rarely affect the GI tract, particularly the small intestine, they should be considered when chronic inflammation with ulceration is observed. The overlapping clinical features between EBV-MCUs and small bowel adenocarcinoma may lead to misdiagnosis, which emphasizes the need for comprehensive evaluation and accurate histopathological analysis. Increased awareness of this rare entity is crucial for timely diagnosis, optimal patient care, and prevention of unnecessary invasive procedures.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hirai T, Japan; Lu H, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Raffeld M, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer--a study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:405-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sinit RB, Horan KL, Dorer RK, Aboulafia DM. Epstein-Barr Virus-Positive Mucocutaneous Ulcer: Case Report and Review of the First 100 Published Cases. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19:e81-e92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4235] [Cited by in RCA: 11365] [Article Influence: 3788.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Dabaja BS, Suki D, Pro B, Bonnen M, Ajani J. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: presentation, prognostic factors, and outcome of 217 patients. Cancer. 2004;101:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aparicio T, Pachev A, Laurent-Puig P, Svrcek M. Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Diagnosis of Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4245] [Cited by in RCA: 5397] [Article Influence: 599.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Morita N, Okuse C, Suetani K, Nakano H, Hiraishi T, Ishigooka S, Mori S, Shimamura T, Asakura T, Koike J, Itoh F, Suzuki M. A rare case of Epstein-Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcer that developed into an intestinal obstruction: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ishikawa E, Satou A, Nakamura M, Nakamura S, Fujishiro M. Epstein-Barr Virus Positive B-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mohammed A, Trujillo S, Ghoneim S, Paranji N, Waghray N. Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma: a Nationwide Population-Based Study. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2023;54:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kentley J, Ooi JL, Potter J, Tiberi S, O'Shaughnessy T, Langmead L, Chin Aleong J, Thaha MA, Kunst H. Intestinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic challenge. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:994-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Roberts TK, Chen X, Liao JJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;5:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |