Published online Jun 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i6.594

Peer-review started: November 22, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 9, 2022

Accepted: May 13, 2022

Article in press: May 13, 2022

Published online: June 27, 2022

Processing time: 216 Days and 20 Hours

Conventional Billroth II (BII) anastomosis after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) for gastric cancer (GC) is associated with bile reflux gastritis, and Roux-en-Y anastomosis is associated with Roux-Y stasis syndrome (RSS). The uncut Roux-en-Y (URY) gastrojejunostomy reduces these complications by blocking the entry of bile and pancreatic juice into the residual stomach and preserving the impulse originating from the duodenum, while BII with Braun (BB) anastomosis reduces the postoperative biliary reflux without RSS. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic URY with BB anastomosis in patients with GC who underwent radical distal gastrectomy.

To evaluate the value of URY in patients with GC.

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Chinese National Know

Eight studies involving 704 patients were included in this meta-analysis. The incidence of reflux gastritis [odds ratio = 0.07, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.03-0.19, P < 0.00001] was significantly lower in the URY group than in the BB group. The pH of the postoperative gastric fluid was lower in the URY group than in the BB group at 1 d [mean difference (MD) = -2.03, 95%CI: (-2.73)-(-1.32), P < 0.00001] and 3 d [MD = -2.03, 95%CI: (-2.57)-(-2.03), P < 0.00001] after the operation. However, no significant difference in all the intraoperative outcomes was found between the two groups.

This work suggests that URY is superior to BB in gastrointestinal reconstruction after LDG when considering postoperative outcomes.

Core Tip: No consensus is available in the literature regarding the more beneficial technique between laparoscopic Uncut Roux-en-Y (URY) and Billroth II combined Braun (BB) anastomosis for radical distal gastrectomy. This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis comparing URY and BB anastomosis. These two techniques were investigated in terms of surgical outcomes, postoperative recovery, and postoperative complications.

- Citation: Jiao YJ, Lu TT, Liu DM, Xiang X, Wang LL, Ma SX, Wang YF, Chen YQ, Yang KH, Cai H. Comparison between laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y and Billroth II with Braun anastomosis after distal gastrectomy: A meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(6): 594-610

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i6/594.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i6.594

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third most common cause of death from cancer[1]. The latest update from 2018 showed that GC accounted for 5.7% of all cancer cases, 8.2% of all deaths related to cancer, and approximately 782685 total deaths, representing a serious threat to human life and health[2]. The development of the treatments used to cure cancer revealed that radiotherapy as well as neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy may improve the outcomes, but surgery (e.g., traditional open surgery and laparoscopic surgery) is the primary option for an effective cure[3].

Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) was reported for the first time in Japan in 1994[4], when it was performed in combination with Billroth I (BI) gastroduodenostomy in a patient with GC at an early stage. It has been subsequently applied in Asia, due to its low trauma and rapid recovery of the patient. To date, a growing number of studies demonstrated that LDG is an oncologic safe alternative to open distal gastrectomy (ODG) in the treatment of early and advanced GC[5-7]. However, the choice of the most appropriate type of gastrointestinal reconstruction after LDG is still under debate.

Gastrointestinal reconstruction is an important part of GC surgery as well as tumor resection and lymph node dissection, since it is necessary to maintain a satisfactory nutritional status and quality of life, with a postoperative morbidity as low as possible[8]. BI reconstruction has the physiological advantage of allowing food passage through the duodenum[9] and reducing the postoperative weight loss[10]. However, the incidence of short-term complications, such as gastrointestinal fistulas classified as Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa or higher, is high in the BI group due to excessive anastomotic tension[11-13]. BII anastomosis resolves the anastomotic tension, but is prone to postoperative complications potentially associated to residual GC such as postoperative biliary reflux, alkaline reflux gastritis, and esophagitis[14]. Roux-en-Y (RY) anastomosis does not cause anastomotic tension, and the gastric content enters directly into the jejunum, reducing the duodenal lumen pressure and the development of delayed gastric emptying and reflux gastritis. However, Roux-Y stasis syndrome (RSS) has an incidence of 10%-30% due to the abnormal activity in the distal jejunum of the anastomosed stomach[15]. On the other hand, postoperative biliary reflux without RSS can be reduced by performing BII with Braun (BB) anastomosis[16,17]. In addition, a new method of reconstructing the digestive tract, “uncut Roux-en-Y (URY) anastomosis”, was introduced in 1988, which is an improvement of the RY anastomosis, since it can effectively prevent the development of RSS, reflux gastritis, and reflux esophagitis[18,19].

Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis were performed by including the most recent and comprehensive studies, to systematically evaluate the safety and efficacy of the two approaches (URY and BB) for the reconstruction surgery of distal gastrectomy.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis statement[20].

A systematic literature search was performed from January 1994 to August 18, 2021 using PubMed, Embase, Web of science, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, Chinese Biomedical Database, and Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP). The following databases were also used in our search: Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov), Data Archiving and Networked Services, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform/the-ictrp-search-portal), and the reference lists of articles and relevant conference proceedings in August 2021. In addition, we conducted a relevant search by Reference Citation Analysis (RCA) (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com). We cited high-quality references using its results analysis functionality. The search strategy used a combination of the Mesh terms and free terms, such as: “Stomach neoplasms” and “laparoscopy or laparoscopes” and “gastroenterostomy” and “gastric bypass”[21]. All the identified studies were imported into Endnote X9 to identify duplicates and screen eligible studies.

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs comparing the outcomes of URY with those of BB anastomosis in the treatment of patients with GC were included in this study. In case of two or more studies from the same author or institution and the overlap of the study intervals or patients involved, the most recent study or the study with the largest sample size was selected. No language restriction was considered in including the studies. The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) Studies that did not include outcomes of interest; (2) Studies that did not show the statistical analysis necessary to perform the meta-analysis; (3) Studies with mixed LDG and ODG groups, unless the LDG-related data were presented separately; (4) Studies that did not specify the type of reconstruction; and (5) Posters, review articles, commentaries, and abstract-only articles. Two reviewers independently evaluated the titles and abstracts and read the full text to identify the eligible studies according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria[22]. A third reviewer could be involved in case of disagreement between the two reviewers.

Bile reflux means the reflux of bile into the stomach. Bile can easily enter the stomach after gastrectomy, causing a series of discomforts such as acid regurgitation, which can lead to reflux gastritis over time. Inflammation and bleeding may occur in the gastric mucosa, as observed using gastroscopy. The definition of reflux gastritis varies from study to study; whenever a postoperative complication in a study reports alkaline reflux gastritis or bile reflux gastritis, it is directly categorized as reflux gastritis. Postoperative gastroparesis is a disorder characterized by delayed gastric emptying of solid food in the absence of a mechanical obstruction of the stomach, resulting in the cardinal symptoms of early satiety, postprandial fullness, nausea, vomiting, belching, and bloating[23]. Postoperative ileus is a transient interruption of coordinated bowel motility after surgical intervention, which prevents the effective transit of the intestinal contents or tolerance of oral intake[24].

Two reviewers independently extracted the data from the eligible studies using a standardized form including the first author, year of publication, number of patients, study design, participant characteristics, operative details, and outcomes. The surgical outcomes included the operative time, time to perform the anastomosis, number of removed lymph nodes, and intraoperative blood loss. Postoperative recovery indicators included the postoperative hospital stay, time to first passage of flatus or defecation, postoperative gastric fluid pH, and time to first solid diet at days 1 and 3 post operation. Postoperative complications included reflux gastritis, gastroparesis, anastomotic leakage, and ileus. If an outcome was observed at different times in the study, the data at the time of the last observation were extracted.

The risk of bias for all the included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool[25]. The domain included the random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. As regards the non-RCTs, the quality of the studies was evaluated using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS)[26] according to three main factors: (1) Selection of the studied groups; (2) Comparability among groups; and (3) Determination of the outcomes. Each study was scored on an NOS of 0-9, with eligible studies with a score of 6 and high quality studies with a score of 8 and above[27].

The meta-analysis was performed using Review manager (Version 5.4). The results of the dichotomous data are expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), while the effect size of the continuous outcomes was measured as the weighted mean difference (MD) with 95%CI. Heterogeneity was assessed by the χ2 test and I2 statistics and was classified as low (I2 < 25%), moderate (25%< I2 < 50%), and high heterogeneity (I2 > 50%)[28]. When the I2 value was less than 50%, a fixed effects model was used; otherwise, a random effects model was used. Evaluation of publication bias was not conducted because less than ten studies were included. Subgroup analysis was conducted to explore the sources of heterogeneity according to the type of study (RCTs and non-RCTs). The considered information was extracted from the published articles; thus, the authors were not contacted for asking the data. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

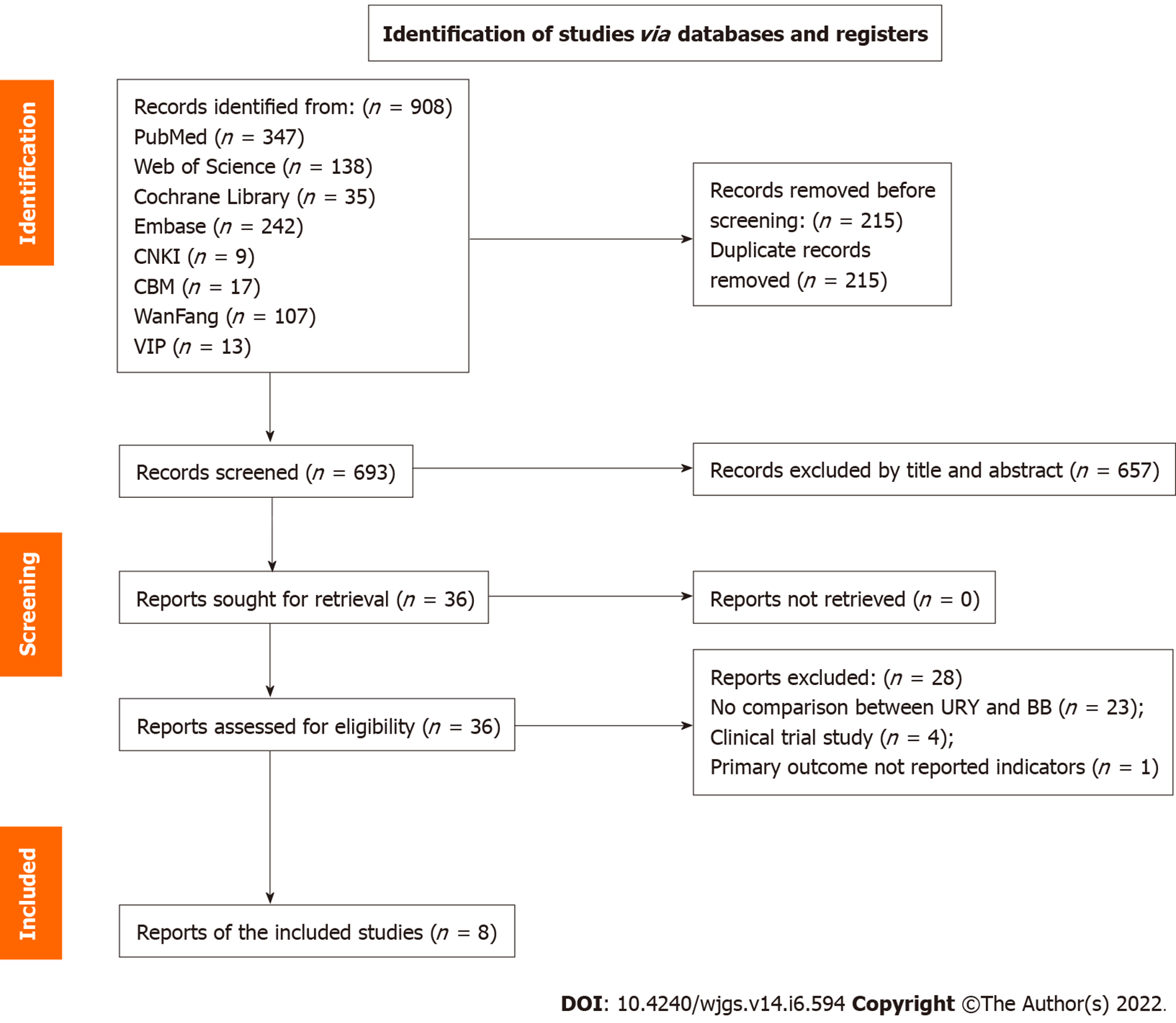

A total of 908 potentially relevant articles were identified, and among these, 36 were selected to read the full text. A total of eight studies were finally included and among them[29-36], three were RCTs[30,31,34] and five were non-RCTs[29,32,33,35,36]. Two reviewers indicated that the techniques of the two anastomosis methods were sufficiently similar so that the results could be pooled. No disagreement occurred between the two reviewers during the study selection process, and all the included articles were chosen after discussion and mutual agreement. The flow diagram of the study selection demonstrating the details of the selection process is shown in Figure 1[37].

The included articles described investigations performed in China and published between 2017 and 2021, and the type of procedure was laparoscopy in all of them. A total of 704 patients were included, and among them, 354 underwent URY and 350 underwent BB. In addition, among them, 272 (38.6% of all the included cases) were from the three included RCTs, and 136 (38.4% of all the URY cases) were in the URY group. The information regarding the characteristics of the included studies is summarized in Table 1. The quality assessment of the RCTs is shown in Table 2. The included RCTs of surgical interventions had certain problems with blinding[38]. The quality of non-RCTs studies had scores between 6 and 8, with a mean of 7.4 (Table 1).

| Ref. | Study type | Country | Period | Number (URY/BB) | Gender (M/F) | Age (URY/BB) | BMI | ASA (I/II/III) | Tumor stage (I/II/III/IV) | Differentiation (H/M/L) | Matched factors1 | NOS score |

| Chen[30], 2018 | RCT | China | 2016.5-2017.9 | URY 30, BB 30 | 17/13, 16/14 | 55.00 ± 5.40, 53.50 ± 7.56 | 22.89 ± 4.23, 21.38 ± 2.02 | NR | 3/10/17/0, 4/12/14/0 | 5/15/10, 4/14/12 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 12 | NA |

| Gao and Xiang[29], 2018 | Retro | China | 2014.1-2017.1 | URY 26, BB 34 | 17/9, 21/13 | 60.61 ± 11.14, 59.72 ± 10.79 | 21.58 ± 1.86, 21.35 ± 1.93 | NR | 0/5/14/7, 0/7/18/9 | 8/7/11, 10/11/13 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 | 8 |

| Li et al[32], 2017 | Retro | China | 2010.1-2016.1 | URY 30, BB 33 | 21/9, 21/12 | 52.81 ± 5.39, 52.09 ± 6.47 | 21.66 ± 2.54, 21.81 ± 2.62 | NR | NG | 8/11/11, 9/12/12 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 12 | 7 |

| Ren et al[31], 2020 | RCT | China | 2015.6-2016.12 | URY 44, BB 44 | 30/14, 28/16 | 59.61 ± 11.14, 59.72 ± 10.79 | 21.51 ± 1.86, 21.38 ± 1.93 | NR | 0/8/25/11, 0/9/23/12 | 14/13/17, 13/14/17 | 1, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 13 | NA |

| Wang et al[36], 2018 | Retro | China | 2015.3-2017.6 | URY 81, BB 58 | 52/29, 46/12 | 56 (30-79), 56.5 (24-77) | NR | NR | 41/20/17/0, 28/13/16/0 | NR | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9 | 8 |

| Wang et al[34], 2021 | RCT | China | 2017.1-2018.5 | URY 62, BB 62 | 44/18, 44/18 | 54.84 ± 8.31; 54.69 ± 10.07 | 22.43 ± 3.07, 22.46 ± 3.17 | 27/28/7, 16/41/5 | NG | NR | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 | NA |

| Wu et al[33], 2021 | Retro | China | 2016.1-2019.4 | URY 45, BB 50 | 27/18, 31/19 | 59.1 ± 6.2, 59.1 ± 6.3 | 23.3 ± 3.0, 23.2 ± 2.9 | NR | 45/0/0/0, 50/0/0/0 | 7/15/23, 8/19/23 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 | 6 |

| Zhou et al[35], 2018 | Retro | China | 2010.6-2015.4 | URY 36, BB 39 | 22/14, 24/15 | 61 ± 5, 61 ± 8 | 23 ± 3, 22 ± 4 | 21/15/0, 23/16/0 | 36/0/0/0, 39/0/0/0 | 11/16/9, 10/19/10 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 13 | 8 |

| Ref. | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blind of participant and personnel | Blind of assessment | Outcome of incomplete data | Selective report | Other bias |

| Chen[30], 2018 | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Ren et al[31], 2020 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Wang et al[34], 2021 | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

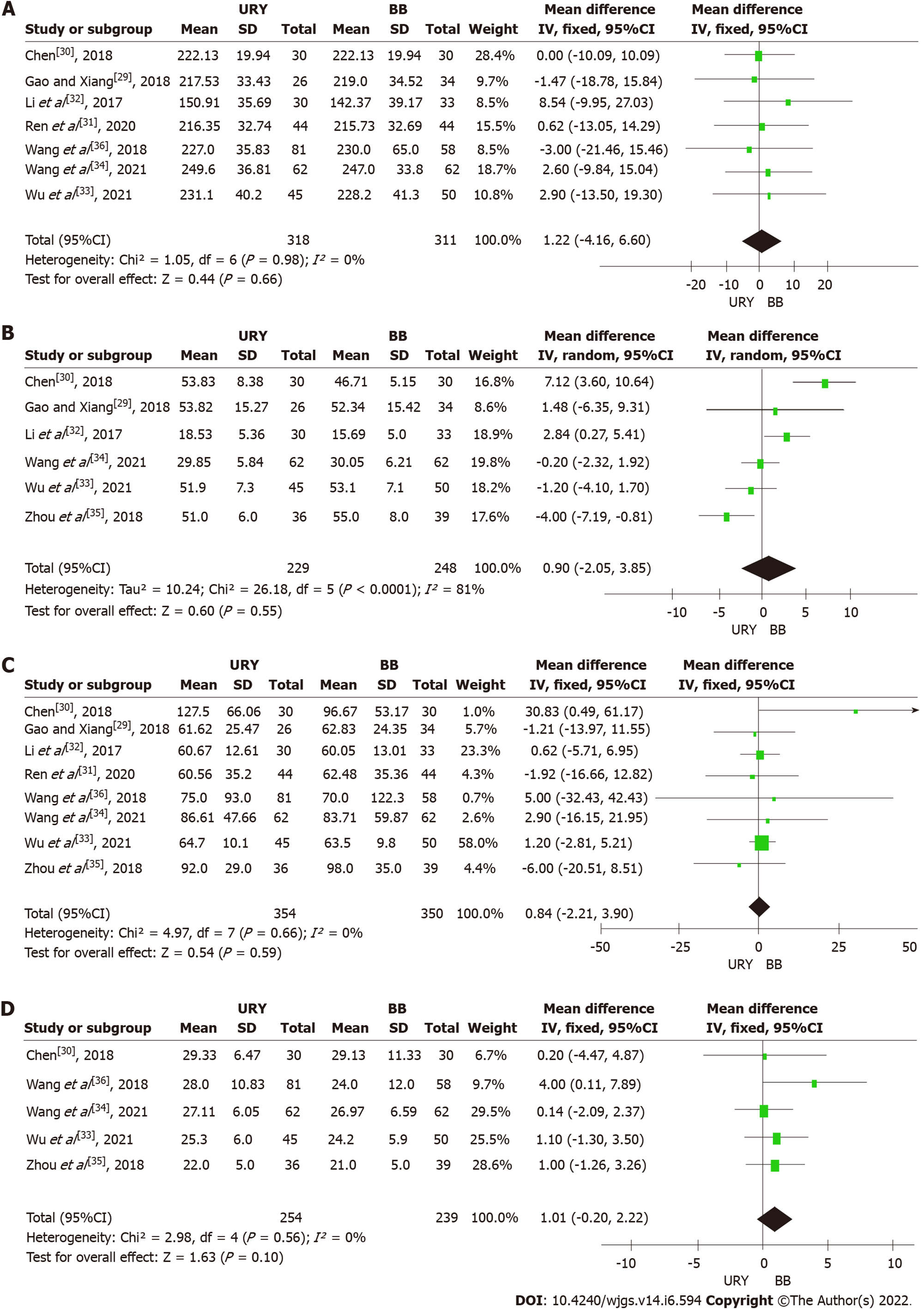

Operative time: Seven studies reported the operative time of the two procedures[29-34,36]. A fixed-effect model was used (χ2 = 1.05, P = 0.98, I2 = 0%) for meta-analysis, revealing that there was no significant difference between the two groups [MD = 1.22, 95%CI: (-4.16)-6.60, P = 0.66] (Figure 2A). The subgroup analysis also revealed no significant difference between the RCTs [MD = 0.93, 95%CI: (-5.87)-7.73, P = 0.79] and non-RCTs subgroups [MD = 1.71, 95%CI: (-7.09)-10.05, P = 0.70] (Table 3).

| Subgroup | Type | No. of studies | No. of patients | Meta-analysis results | Assessment of heterogeneity | |||

| URY | BB | OR/MD (95%CI) | P value | I² | P value | |||

| Operative time | RCTs | 3 | 136 | 136 | 0.93 [(-5.87)-7.73] | 0.79 | 0 | 0.95 |

| Non-RCTs | 4 | 182 | 175 | 1.71 [(-7.09)-10.51] | 0.70 | 0 | 0.82 | |

| Reconstruction time | RCTs | 2 | 92 | 92 | 3.32 [(-3.85)-10.49] | 0.36 | 0.92 | 0.0005 |

| Non-RCTs | 4 | 137 | 156 | -0.41 [(-3.85)-3.03] | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.0009 | |

| Intraoperative blood loss | RCTs | 3 | 136 | 136 | 3.87 [(-7.02)-14.75] | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.16 |

| Non-RCTs | 4 | 218 | 214 | 0.58 [(-2.60)-3.77] | 0.72 | 0 | 0.91 | |

| Total number of harvested lymph nodes | RCTs | 2 | 92 | 92 | 0.15 [(-1.86)-2.16] | 0.88 | 0 | 0.98 |

| Non-RCTs | 3 | 163 | 147 | 1.90 [(-0.14)-3.94] | 0.07 | 0 | 0.39 | |

| Time to first passage of flatus or defecation | RCTs | 2 | 106 | 106 | -0.26 [(-0.87)-0.34] | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.04 |

| Non-RCTs | 5 | 218 | 214 | -0.29 [(-0.59)-0.01] | 0.05 | 0.56 | 0.06 | |

| Time to first solid diet | RCTs | 1 | 44 | 44 | -0.05 [(-1.14)-1.04] | 0.93 | Not applicable | |

| Non-RCTs | 4 | 173 | 164 | -0.29 [(-0.53)-(-0.05)] | 0.02 | 0 | 0.67 | |

| Postoperative hospitalization time | RCTs | 2 | 106 | 106 | -0.01 [(-0.16)-0.14)] | 0.87 | 0 | 0.84 |

| Non-RCTs | 5 | 218 | 214 | -0.26 [(-0.78)-0.26] | 0.32 | 0 | 0.63 | |

| Reflux gastritis | RCTs | 2 | 92 | 92 | 0.03 (0.01-0.11) | < 0.00001 | 0 | 0.70 |

| Non-RCTs | 3 | 193 | 209 | 0.15 (0.03-0.66) | 0.01 | 0 | 0.77 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | RCTs | 2 | 106 | 106 | 0.73 (0.15-3.48) | 0.69 | Not applicable | |

| Non-RCTs | 3 | 107 | 123 | 1.16 (0.23-5.87) | 0.85 | 0 | 0.85 | |

Reconstruction time: Six studies compared the reconstruction time necessary to perform URY and BB[29,30,32-35]. A high heterogeneity (I2 = 81%) was observed among inter-studies; thus, a random effects model was used. The results demonstrated that the reconstruction time was similar between the URY group and BB group [MD = 0.90, 95%CI: (-2.05)-3.85, P = 0.55] (Figure 2B). Moreover, the subgroup analysis did not find any statistically significant difference between the two subgroups [RCTs: MD = 3.32, 95%CI: (-3.85)-10.49, P = 0.36; non-RCTs: MD = -0.41, 95%CI: (-3.85)-3.03, P = 0.81] (Table 3).

Intraoperative blood loss: The intraoperative blood loss was reported in all studies. The evidence suggested a small difference in the intraoperative blood loss between the URY and BB groups [MD = 0.84, 95%CI: (-2.21)-3.90, P = 0.59] (Figure 2C). The meta-analysis among the RCTs indicated no significant difference in the intraoperative blood loss between the two groups [MD = 3.87, 95%CI: (-7.02)-14.75, P = 0.49] with low statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.49, I2 = 45%). The pooled data in the non-RCTs revealed a similar result [MD = 0.58, 95%CI: (-2.60)-3.77, P = 0.72] with the absence of statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.91, I2 = 0%) (Table 3).

Total number of harvested lymph nodes: Five articles reported the total number of harvested lymph nodes[30,33-36]. A fixed effect model was used, which showed a low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The pooled result revealed no significant difference between the two groups [MD = 1.01, 95%CI: (-0.20)-2.22, P = 0.10] (Figure 2D). The subgroup analysis showed no evident statistical difference in the total number of harvested lymph nodes between the URY and BB groups in both the RCT and non-RCT subgroups [RCTs: MD = 0.15, 95%CI: (-1.86)-2.16, P = 0.88; non-RCTs: MD = 1.90, 95%CI: (-0.14)-3.95, P = 0.05] (Table 3).

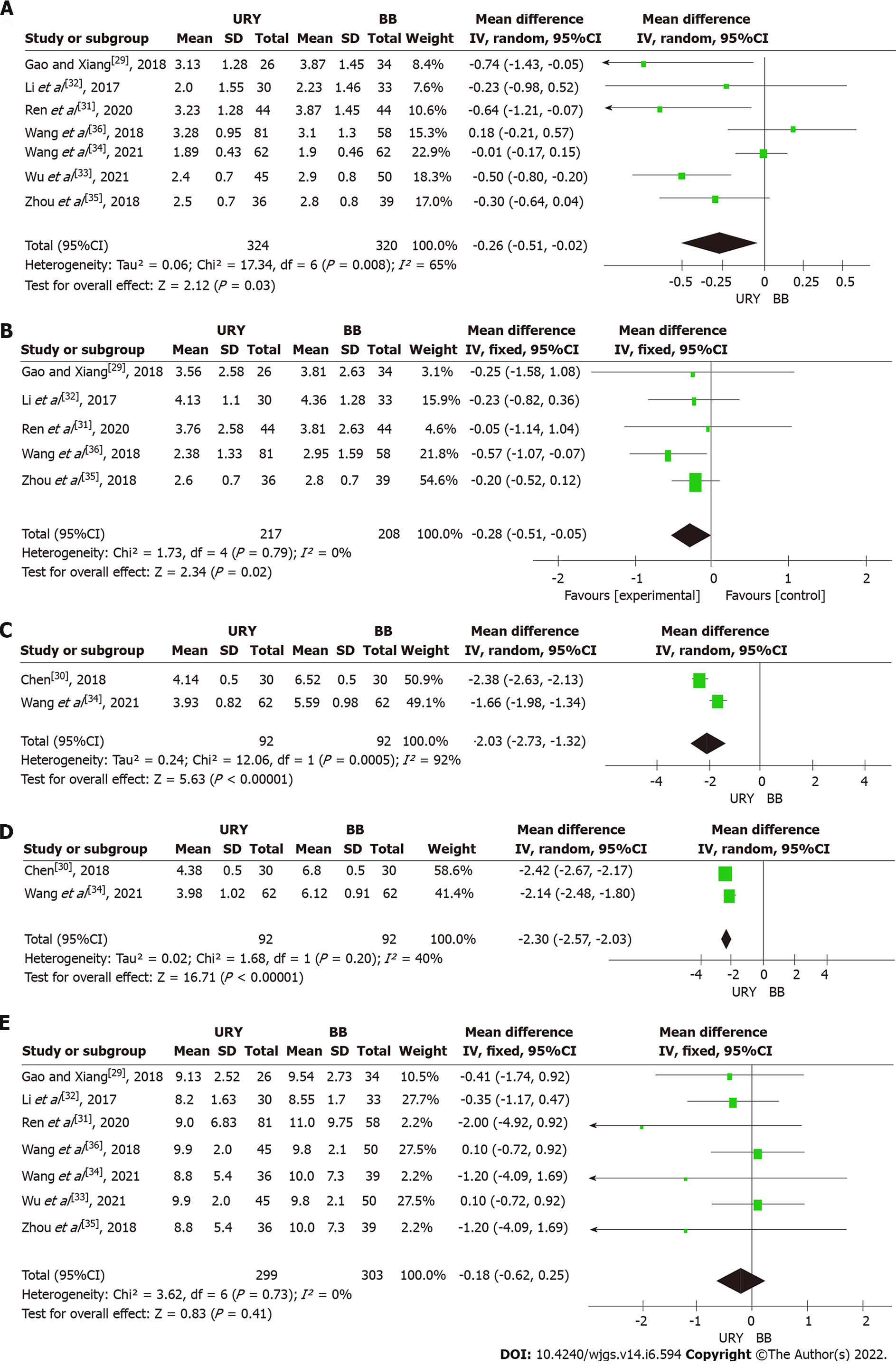

Time to first passage of flatus or defecation: Seven studies involving 644 patients reported the time to first passage of flatus or defecation[29,31-36]. The meta-analysis revealed that URY was associated with a shorter time to first passage of flatus or defecation than BB [MD = -0.26, 95%CI: (-0.51)-(-0.02), P = 0.03] (Figure 3A). A significant heterogeneity was observed among studies (χ2 = 17.34, P = 0.008, I2 = 65%); thus, a random effects model was used. However, no significant difference was found after performing the subgroup analysis between the non-RCT and RCT subgroups [RCTs: MD = -0.26, 95%CI: (-0.87)-0.34, P = 0.40; non-RCTs: MD = -0.29, 95%CI: (-0.59)-0.01, P = 0.05] (Table 3).

Time to first solid diet: Five studies contributed to the meta-analysis regarding this parameter[29,31,32,35,36]. A fixed effects model was used due to a low heterogeneity (I² = 0%). The meta-analysis results showed a significant difference in the time to first solid diet between the URY and BB groups [MD = -0.28, 95%CI: (-0.51)-(-0.05), P = 0.02] (Figure 3B). The subgroup analysis revealed that the URY group had a shorter time to first solid diet than the BB [MD = -0.29, 95%CI: (-0.53)-(-0.05), P = 0.02] in the non-RCTs subgroup, while no statistically significant difference between the two groups was found in the RCT subgroup [MD = -0.05, 95%CI: (-1.14)-1.04, P = 0.93] (Table 3).

Postoperative gastric fluid pH: Two RCTs reported the postoperative pH of the gastric fluid[30,34]. The pooled result on days 1 and 3 revealed that this parameter was superior in the URY than in BB [day 1: MD = -2.03, 95%CI: (-2.73)-(-1.32), P < 0.00001 (Figure 3C); day 3: MD = -2.30, 95%CI: (-2.57)-(-2.03), P < 0.00001 (Figure 3D)]. However, a high heterogeneity was observed in the postoperative gastric fluid pH between days 1 and 3 (I2 = 92% and I2 = 40%, respectively).

Postoperative length of hospital stay: Seven articles reported the postoperative length of hospital stay[29,31-36]. A fixed effects model was used because no significant heterogeneity was present among studies (I2 = 0%). The meta-analysis revealed no significant difference between the two groups [MD = -0.18, 95%CI: (-0.62)-0.25, P = 0.41] (Figure 3E). The subgroup analysis also showed no statistically significant difference between the URY and BB groups in both the non-RCT subgroup [MD = -0.26, 95%CI: (-0.78)-0.26, P = 0.32] and RCT subgroup [MD = -0.01, 95%CI: (-0.16)-0.14, P = 0.87] (Table 3).

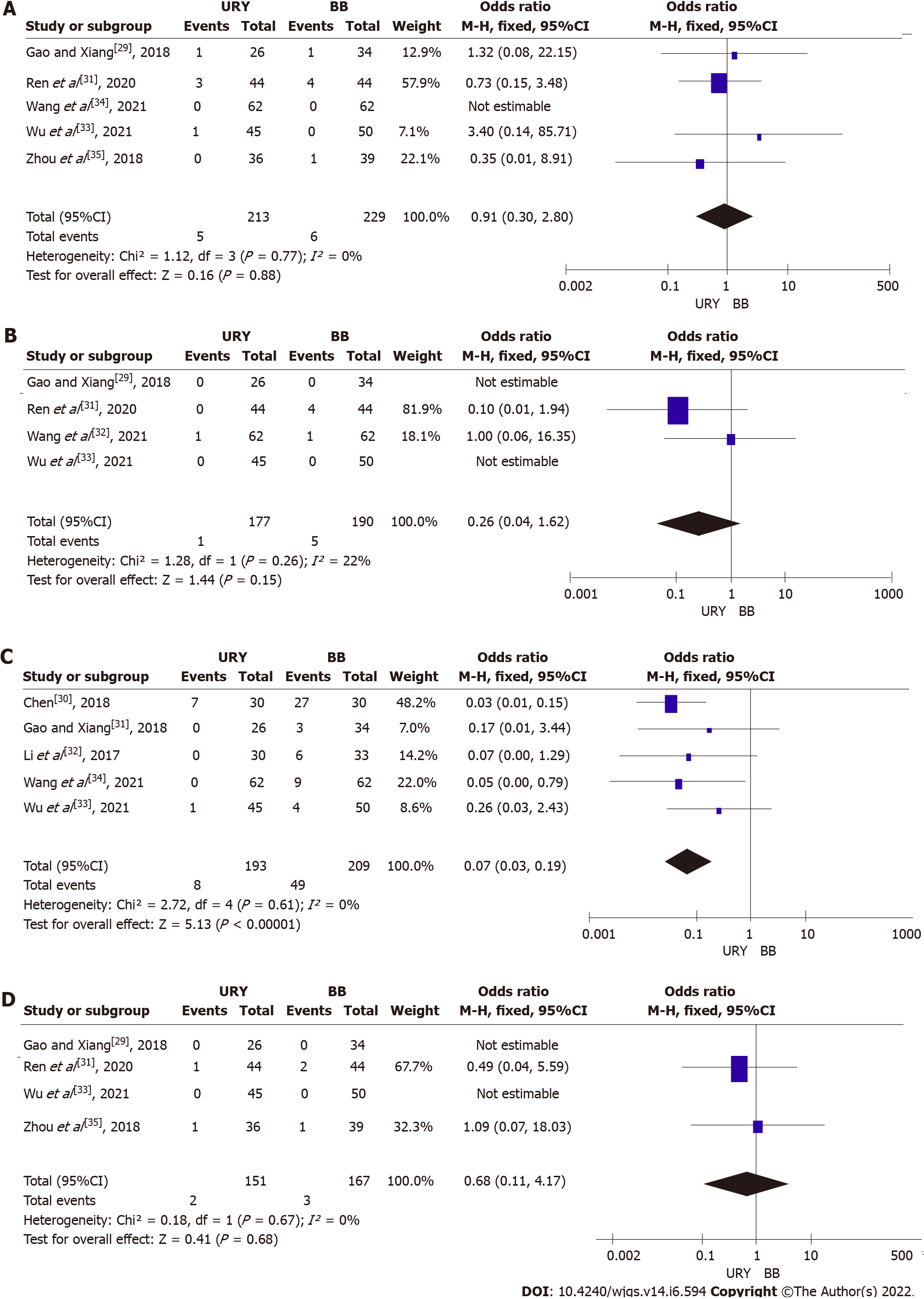

Anastomotic leakage: Five studies reported the presence of anastomotic leakage[29,31,32-35]. A fixed effects model was used (I2 = 0%) due to a low heterogeneity. The incidence of postoperative anastomotic leakage was similar between the URY and BB groups (OR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.30-2.80; P = 0.88) (Figure 4A). The subgroup analysis between RCTs and non-RCTs indicated no significant difference in postoperative anastomotic leakage between the two groups (RCTs: OR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.15-3.48, P = 0.69; non-RCTs: OR = 1.16, 95%CI: 0.23-5.87, P = 0.85) (Table 3).

Ileus: Four articles reported the incidence of postoperative ileus[29,31,33,34]. The meta-analysis showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR = 0.26, 95%CI: 0.04-1.62, P = 0.15). However, a low heterogeneity (I2 = 22%) was observed among studies, and a fixed effects model was used (Figure 4B).

Reflux gastritis: Five studies compared the reflux gastritis between the two groups[29,30,32-34]. A fixed effects model was used due to a low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The incidence of reflux gastritis was significantly lower in the URY group than in the BB group (OR = 0.07; 95%CI: 0.03-0.19; P < 0.00001) (Figure 4C). The subgroup analysis showed that the incidence of reflux gastritis was lower in the URY group than in the BB group, regardless of the subgroup RCT or non-RCT (RCTs: OR = 0.03, 95%CI: 0.01-0.11, P < 0.00001; non-RCTs: OR = 0.15, 95%CI: 0.03-0.66, P = 0.01) (Table 3).

Gastroparesis: A total of four studies reported the incidence of postoperative gastroparesis[29,31,33,35], and among them, two had an incidence of 0[29,33]. The meta-analysis revealed that the incidence of postoperative gastroparesis was not significantly different between the two groups (OR = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.11-4.17, P = 0.68), and it was without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 4D).

In the present study, a sensitivity analysis was performed on the operative time, intraoperative bleeding, reconstruction time, total number of harvested lymph nodes, time to first passage of flatus or defecation, time to first solid diet, postoperative hospitalization time, anastomotic leakage, and reflux gastritis to explore the stability of the included studies by the removal of each study from the meta-analysis and then examining the impact of the removed study on the overall composite estimate. After the exclusion of the relevant studies, when the CIs were within 95%, no significant effect was observed on the overall combined results.

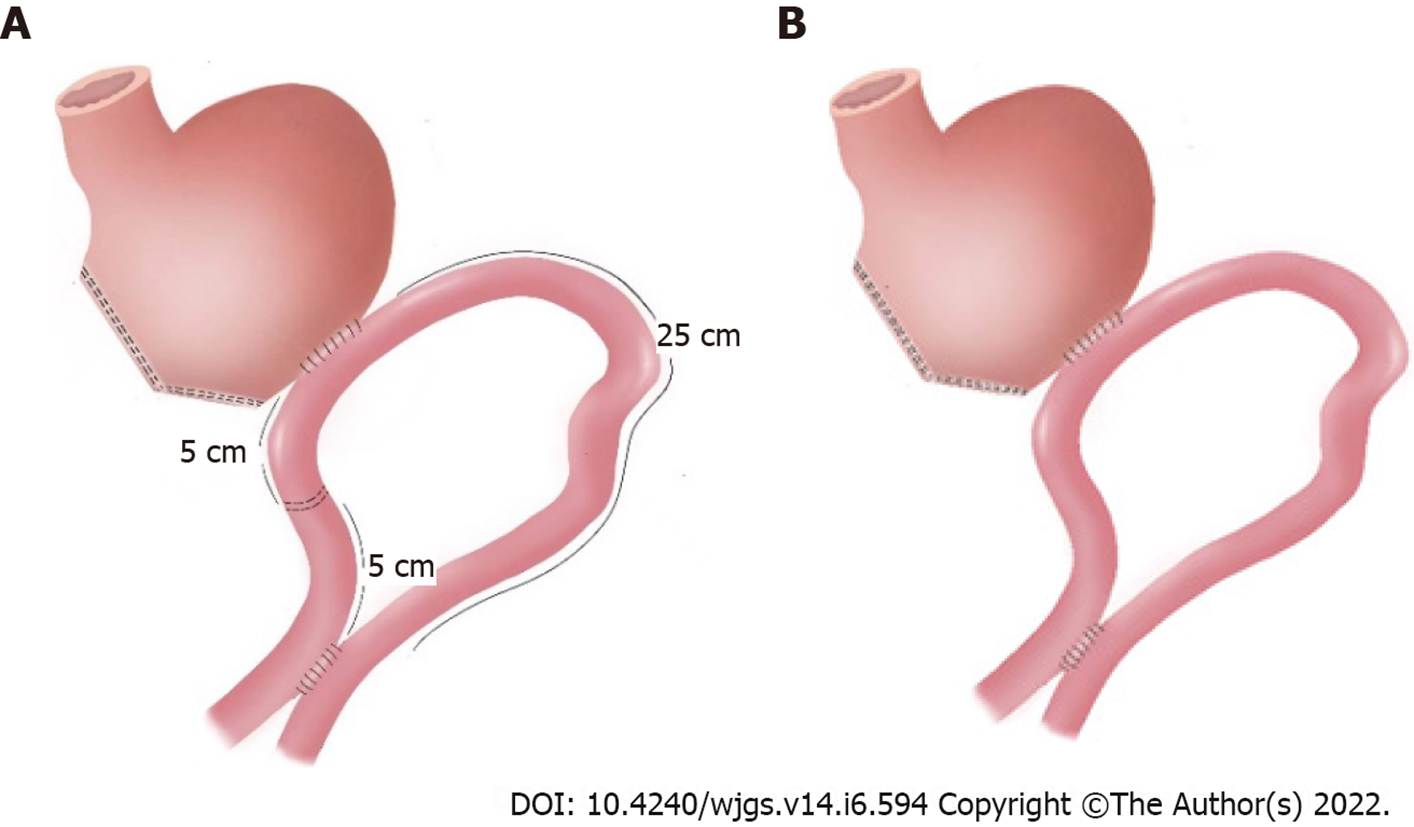

No consensus exists on the most appropriate method to reconstruct the digestive tract for reducing complications and improving the quality of life after LDG. BII reconstruction has been a commonly used anastomosis method nowadays. However, bile reflux occurs frequently after BII due to the structural defects of this type of reconstruction. Therefore, BB’s anastomosis was designed specifically to reduce the flow of bile into the stomach[17], actually also reducing ileus and postoperative gastrointestinal symptoms[16]. URY reconstruction was first reported by Van Stiegman et al[39] in 1988. URY gastrojejunostomy is an improved technique composed of the BII procedure and the BB anastomosis, which includes the additional step of closing the jejunal lumen proximal to the gastrojejunostomy[40]. At the end of distal gastrectomy, a gastrojejunostomy is performed between the residual stomach and the jejunum, approximately 30 cm away from the ligament of Treitz. The side-to-side or end-to-side gastrojejunostomy is performed more often selecting the greater curvature of the residual stomach. Then, a side-to-side jejunojejunostomy is established between the afferent and efferent jejunal limbs, approximately 20 cm distal from the ligament of Treitz and 40 cm distal from the gastrojejunostomy site. Finally, the jejunal lumen is occluded at a site 5 cm proximal to the gastrojejunostomy using different methods[40]. The common methods of jejunal occlusion without transection are the following: Stapling with non-bladed six-row linear staplers or four-row staplers (knifeless GIA, Covidien), placement of four or five tightly tied 3-0 polypropylene seromuscular stitches circularly around the jejunal wall, and jejunal ligature with No. 7 silk and reinforcement by suturing the serosal layers of the upper and lower jejunum at the occlusion site. This anastomosis is considered as a controversial but promising method for gastrointestinal reconstruction after distal gastrectomy. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to evaluate and compare the safety and efficacy of URY reconstruction (Figure 5A) and BB reconstruction (Figure 5B) after distal gastrectomy.

Eight studies involving 704 patients were included in this meta-analysis, divided into 354 who received URY and 350 who received BB[29-36]. No statistical difference in surgical outcomes between the two groups was observed in terms of operative time, intraoperative bleeding, reconstruction time, and lymph node dissection. Our analysis revealed that the reconstruction time had a high degree of heterogeneity both in the total and subgroup analyses, which might be due to factors such as study design, proficiency of the surgeon in performing anastomosis, and cooperation within the surgical team. Our results were like those of a previous study[41], except for the fact that URY in our study had a shorter operative time as well as reconstruction time. This might be due to differences in surgical experience among different reconstructive procedures that might lead to biased results and inconsistent reconstructive approaches (in vivo or ex vivo).

During the postoperative recovery, the mean gastric pH at days 1 and 3 post operation and time to first solid diet were significantly shorter in the URY group than in the BB group. However, the heterogeneity of these observations in our study was high. This might be related to Chen[30]’s study because the author did not use a new negative pressure drainage tube in a timely manner at the beginning of the study to measure the postoperative gastric fluid, leading to a large error in measuring the pH of the gastric fluid in the experimental group in the early stage. The sensitivity analysis of the time to first passage of flatus or defecation, time to first solid diet, and post-operative hospitalization time showed consistency. In addition, URY did not increase the postoperative length of stay compared to BB, which was consistent with the results of Park and Kim[41] and Chen et al[42]. The time to first passage of flatus or defecation in the URY group was shorter than that in the BB group. However, the subgroup analysis showed significance only in the non-RCTs with high heterogeneity, and it was also highly subjective; thus, our results should be interpreted with caution.

In terms of postoperative complications, the URY group had a lower incidence of postoperative reflux gastritis. This result is probably due to the fact that duodenal secretions are diverted to the distal jejunum though the jejunojejunostomy after URY anastomosis compared to BB anastomosis[16]. The uncut limb during the URY procedure preserved the original normal electrical conduction and direction of conduction[40]. This dual action promotes the normal recovery of the postoperative intestinal motility. Reflux gastritis is commonly observed in patients who underwent DG. Endoscopy remains the cornerstone of the diagnosis; the characteristic endoscopic features are adherent mucus, edema, mucosal friability, and erosions. The medical treatment includes antacids and cholestyramine alone or together. Severe cases require surgical treatment. Our study shows that URY is a good way to avoid postoperative reflux gastritis in patients subjected to LDG. Noh et al[43] reported that uncircumcised gastrojejunal RY anastomosis prevents RSS and reduces the alkaline reflux gastritis compared with conventional surgery. A recent clinical study by Park and Kim[41] also indicated that sufficient evidence is available to demonstrate that URY anastomosis reduces postoperative gastritis, duodenal secretion reflux, and gastric residuals. No significant difference in the probability of anastomotic leakage, gastroparesis, or ileus was found in the postoperative period between the two groups. Ma et al[44] demonstrated that URY does not increase the occurrence of postoperative anastomotic leakage and gastrointestinal motility dysfunction for conventional anastomoses.

Although gastrojejunostomy RY anastomosis is an effective method to prevent bile reflux gastritis after DG surgery, the incidence of postoperative RSS is high, seriously affecting the quality of life of patients. URY is a reliable anastomosis after distal radical GC surgery, resulting in few postoperative complications[45], with a lower incidence of RSS compared to RY[18,46,47]. URY gastrojejunostomy reduces RSS by maintaining jejunal continuity (through normal conduction of myoelectric pulses), thereby maintaining the conduction of duodenal pacemaker activity[47]. BI reconstruction is one of the most popular reconstructive procedures after DG, and the incidence of postoperative complications is low; thus, it is considered a good option for surgeons[48]. However, it is not suitable for severe GC cases that require extensive dissection of the stomach, since this approach can lead to excessive anastomotic tension[11]. Our study also demonstrated that the postoperative complication rates after URY were significantly lower than those after BB. Thus, URY might be considered the primary option for reducing the incidence of reflux gastritis and RSS.

Our meta-analysis has several advantages. First, it is the first study comparing URY with BB anastomosis. Second, unlike the comparison of the procedures in previous works, our work considered BB because the URY gastrojejunostomy is a modification of the BII procedure with the BB anastomosis. Third, all the extracted data were cross-checked, and subgroup analysis was performed according to the type of the included studies to improve the credibility of our results. However, several limitations were also present in this study. First, most of the included studies were conducted in tertiary centers, and the recruited patients were carefully selected and had relatively low morbidity and low body mass index, which might result in a limited generalization of these findings. Second, the included studies are mostly observational ones, thus, with a potential selection bias. Third, the included RCTs have a certain bias in the implementation of blinding. This is inevitable because the surgeon cannot perform the procedure without knowing the assigned procedure. Therefore, a large sample size and a rigorously designed RCT are needed to confirm our results. Finally, all the LDG procedures were performed in China, probably because the incidence of GC is higher in East Asia than in most Western countries and distal tumors are more common in Eastern countries[2,49]. Nonetheless, our study provides clinical evidence for surgeons in deciding the optimal reconstruction technique for their patients. Moreover, our hope is that this topic can attract the attention of surgeons in more countries.

URY anastomosis is a safe and effective technique after LDG, and it is better than BB in terms of early postoperative recovery, postoperative gastric juice pH close to normal, and low incidence of reflux gastritis; thus, it can be recommended for gastrointestinal reconstruction after LDG. However, a rigorous RCT design and larger sample size cohorts (including long-term follow-up data) are still necessary to confirm our conclusions.

Gastric cancer (GC) patients have a poor prognosis and high mortality. The efficacy and safety of uncut Roux-en-Y (URY) anastomosis after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) are still controversial.

The URY gastrojejunostomy reduces these complications by blocking the entry of bile and pancreatic juice into the residual stomach and preserves the impulse originating from the duodenum, while BII combined Braun (BB) anastomosis reduces the postoperative biliary reflux without Roux-Y stasis syndrome. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic URY with BB anastomosis in patients with GC who underwent radical distal gastrectomy.

The purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the application value of URY anastomosis in LDG.

PubMed, Embase, Web of science, Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, Chinese Biomedical Database, and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals (VIP) were used to search relevant studies published from January 1994 to August 18, 2021. The following databases were also used in our search: Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov), Data Archiving and Networked Services, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform/the-ictrp-search-portal), and the reference lists of articles and relevant conference proceedings in August 2021. In addition, we conducted a relevant search by Reference Citation Analysis (RCA) (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com). We cited high-quality references using its results analysis functionality. The methodological quality of the eligible randomized clinical trials (RCTs) was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, and the non-RCTs were evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager (Version 5.4).

Eight studies involving 704 patients were included in this meta-analysis. The incidence of reflux gastritis [odds ratio = 0.07, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.03-0.19, P < 0.00001) was significantly lower in the URY group than in the BB group. The pH of the postoperative gastric fluid was lower in the URY group than in the BB group at 1 d [mean difference (MD) = -2.03, 95%CI: (-2.73)-(-1.32), P < 0.00001] and 3 d [MD = -2.03, 95%CI: (-2.57)-(-2.03), P < 0.00001] after the operation. However, no significant difference in all the intraoperative outcomes was found between the two groups.

This work demonstrated that URY is superior to BB in patients with GC when the postoperative outcome is considered. Therefore, this evidence supports the recommendation of URY gastrojejunostomy for gastrointestinal reconstruction after LDG.

Several limitations were present in this study. First, most of the included studies were conducted in tertiary centers, and the recruited patients were carefully selected and had relatively low morbidity and low body mass index, which might result in a limited generalization of these findings. Second, the included studies are mostly observational ones, thus, with a potential selection bias. Third, the included RCTs has a certain bias in the implementation of blinding. This is inevitable because the surgeon cannot perform the procedure without knowing the assigned procedure. Therefore, a large sample size and a rigorously designed RCTs are needed for confirming our results. Finally, all the LDG procedures were performed in China, probably because the incidence of GC is higher in East Asia than in most Western countries and distal tumors are more common in Eastern countries. Moreover, our hope is that this topic can attract the attention of surgeons in more countries.

The authors thank the Key Laboratory of Molecular Diagnostics and Precision Medicine for Surgical Oncology in Gansu Province and the DaVinci Surgery System Database (DSSD, http://www.davincisurgerydatabase.com) for their help and support in the methodology and meta-analysis process. Thanks to Rui Yang of Ningxia Medical University for her help with the article graphics.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: Gansu Provincial Hospital.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chue KM, Singapore; Masaki S, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Suh YS, Lee J, Woo H, Shin D, Kong SH, Lee HJ, Shin A, Yang HK. National cancer screening program for gastric cancer in Korea: Nationwide treatment benefit and cost. Cancer. 2020;126:1929-1939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55768] [Article Influence: 7966.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 3. | Mocan L. Surgical Management of Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146-148. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yakoub D, Athanasiou T, Tekkis P, Hanna GB. Laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: is it an alternative to the open approach? Surg Oncol. 2009;18:322-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Best LM, Mughal M, Gurusamy KS. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD011389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen X, Feng X, Wang M, Yao X. Laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and high-quality nonrandomized comparative studies. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:1998-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Piessen G, Triboulet JP, Mariette C. Reconstruction after gastrectomy: which technique is best? J Visc Surg. 2010;147:e273-e283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kalmár K, Németh J, Kelemen D, Agoston E, Horváth OP. Postprandial gastrointestinal hormone production is different, depending on the type of reconstruction following total gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2006;243:465-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Terashima M, Tanabe K, Yoshida M, Kawahira H, Inada T, Okabe H, Urushihara T, Kawashima Y, Fukushima N, Nakada K. Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45 and changes in body weight are useful tools for evaluation of reconstruction methods following distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S370-S378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xiong JJ, Altaf K, Javed MA, Nunes QM, Huang W, Mai G, Tan CL, Mukherjee R, Sutton R, Hu WM, Liu XB. Roux-en-Y versus Billroth I reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1124-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Van Cutsem E, Sagaert X, Topal B, Haustermans K, Prenen H. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:2654-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1282] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 162.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shoji Y, Kumagai K, Ida S, Ohashi M, Hiki N, Sano T, Nunobe S. Features of the complications for intracorporeal Billroth-I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:1425-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kumagai K, Shimizu K, Yokoyama N, Aida S, Arima S, Aikou T; Japanese Society for the Study of Postoperative Morbidity after Gastrectomy. Questionnaire survey regarding the current status and controversial issues concerning reconstruction after gastrectomy in Japan. Surg Today. 2012;42:411-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Masui T, Kubora T, Nakanishi Y, Aoki K, Sugimoto S, Takamura M, Takeda H, Hashimoto K, Tokuka A. The flow angle beneath the gastrojejunostomy predicts delayed gastric emptying in Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cui LH, Son SY, Shin HJ, Byun C, Hur H, Han SU, Cho YK. Billroth II with Braun Enteroenterostomy Is a Good Alternative Reconstruction to Roux-en-Y Gastrojejunostomy in Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:1803851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vogel SB, Drane WE, Woodward ER. Clinical and radionuclide evaluation of bile diversion by Braun enteroenterostomy: prevention and treatment of alkaline reflux gastritis. An alternative to Roux-en-Y diversion. Ann Surg. 1994;219:458-65; discussion 465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sun MM, Fan YY, Dang SC. Comparison between uncut Roux-en-Y and Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2628-2639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang D, He L, Tong WH, Jia ZF, Su TR, Wang Q. Randomized controlled trial of uncut Roux-en-Y vs Billroth II reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Which technique is better for avoiding biliary reflux and gastritis? World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6350-6356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Pieper D, Buechter RB, Li L, Prediger B, Eikermann M. Systematic review found AMSTAR, but not R(evised)-AMSTAR, to have good measurement properties. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:574-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:944-52.. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li J, Gao W, Punja S, Ma B, Vohra S, Duan N, Gabler N, Yang K, Kravitz RL. Reporting quality of N-of-1 trials published between 1985 and 2013: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;76:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim D, Gedney R, Allen S, Zlomke H, Winter E, Craver J, Pinnola AD, Lancaster W, Adams D. Does etiology of gastroparesis determine clinical outcomes in gastric electrical stimulation treatment of gastroparesis? Surg Endosc. 2021;35:4550-4554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bragg D, El-Sharkawy AM, Psaltis E, Maxwell-Armstrong CA, Lobo DN. Postoperative ileus: Recent developments in pathophysiology and management. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:367-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18487] [Cited by in RCA: 24762] [Article Influence: 1768.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 26. | Luchini C, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World J Meta-Anal. 2017;5:80-84. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 617] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 69.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (82)] |

| 27. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 12610] [Article Influence: 840.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 25756] [Article Influence: 1119.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gao DS, Xiang BH. Study of different anastomoses of B-II+Braun and Uncut Roux-en-Y in radical surgery for distal gastric cancer. Zhejiang Clinical Medical Journal. 2018;20:3. |

| 30. | Chen LF. The contrast on effect of nondetached Roux-en-Y and BillrothII plus Braun on prevention of bile reflux postoperative gastric cancer. Lanzhou University, 2018. |

| 31. | Ren N, Liu XL, Wei LM, Cui JF. Comparison of Billroth II combining Braun anastomosis and Roux-en-Y anastomosis in laparoscopic distal gastric cancer surgery. Chin J Curr Adv Gen Surg. 2020;23:197-199, 206. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Li ST, Ji G, Fen J, Zhang B, Wang LR, Liu ZH, Yang YJ. Comparison of the results of different methods of gastrointestinal tract reconstruction in laparoscopic distal gastric cancer surgery. Med J National Defending Forces Southwest China. 2017;27:717-719. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Wu SH, Liu SH, Zhou F. Clinical comparative study of different anastomosis methods of B-II+Braun and Uncut Roux-en-Y during radical laparoscopic radical gastrectomy. J Clin Surg. 2021;29:154-157. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Wang J, Wang Q, Dong J, Yang K, Ji S, Fan Y, Wang C, Ma Q, Wei Q, Ji G. Total Laparoscopic Uncut Roux-en-Y for Radical Distal Gastrectomy: An Interim Analysis of a Randomized, Controlled, Clinical Trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhou JF, He QL, Wang JX, Qian HY. Application value of different digestive tract reconstruction methods in labparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Chin J Dig Surg. 2018;17:592-598. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Wang Y, Li Z, Shan F, Zhang L, Li S, Jia Y, Chen Y, Xue K, Miao R, Gao X, Yan C, Wu Z, Ji J. [Comparison of the safety and the costs between laparoscopic assisted or totally laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y and BillrothII(+Braun reconstruction--a single center prospective cohort study]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;21:312-317. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 40061] [Article Influence: 10015.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 38. | McCulloch P, Taylor I, Sasako M, Lovett B, Griffin D. Randomised trials in surgery: problems and possible solutions. BMJ. 2002;324:1448-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 553] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Van Stiegmann G, Goff JS. An alternative to Roux-en-Y for treatment of bile reflux gastritis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;166:69-70. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Huang Y, Wang S, Shi Y, Tang D, Wang W, Chong Y, Zhou H, Xiong Q, Wang J, Wang D. Uncut Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:1341-1347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Park JY, Kim YJ. Uncut Roux-en-Y Reconstruction after Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy Can Be a Favorable Method in Terms of Gastritis, Bile Reflux, and Gastric Residue. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14:229-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chen XJ, Chen YZ, Chen DW, Chen YL, Xiang J, Lin YJ, Chen S, Peng JS. The Development and Future of Digestive Tract Reconstruction after Distal Gastrectomy: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cancer. 2019;10:789-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Noh SM. Improvement of the Roux limb function using a new type of "uncut Roux" limb. Am J Surg. 2000;180:37-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ma Y, Li F, Zhou X, Wang B, Lu S, Wang W, Yu S, Fu W. Four reconstruction methods after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Park YS, Shin DJ, Son SY, Kim KH, Park DJ, Ahn SH, Kim HH. Roux Stasis Syndrome and Gastric Food Stasis After Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy with Uncut Roux-en-Y Reconstruction in Gastric Cancer Patients: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. World J Surg. 2018;42:4022-4032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Jangjoo A, Mehrabi Bahar M, Aliakbarian M. Uncut Roux-en-y esophagojejunostomy: A new reconstruction technique after total gastrectomy. Indian J Surg. 2010;72:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Tu BN, Kelly KA. Elimination of the Roux stasis syndrome using a new type of "uncut Roux" limb. Am J Surg. 1995;170:381-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kim MS, Kwon Y, Park EP, An L, Park H, Park S. Revisiting Laparoscopic Reconstruction for Billroth 1 Versus Billroth 2 Versus Roux-en-Y After Distal Gastrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in the Modern Era. World J Surg. 2019;43:1581-1593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Strong VE, Song KY, Park CH, Jacks LM, Gonen M, Shah M, Coit DG, Brennan MF. Comparison of gastric cancer survival following R0 resection in the United States and Korea using an internationally validated nomogram. Ann Surg. 2010;251:640-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |