Published online May 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.514

Peer-review started: January 8, 2022

First decision: March 13, 2022

Revised: April 1, 2022

Accepted: May 7, 2022

Article in press: May 7, 2022

Published online: May 27, 2022

Processing time: 136 Days and 21.2 Hours

Castleman disease is an uncommon nonclonal lymphoproliferative disorder, which frequently mimics both benign and malignant abnormalities in several regions. Depending on the number of lymph nodes or regions involved, Castleman disease (CD) varies in diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. It rarely occurs in the pancreas alone without any distinct clinical feature and tends to be confused with pancreatic paraganglioma (PGL), neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), and primary tumors, thus impeding proper diagnosis and treatment.

A 28-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the neck of the pancreas, detected by ultrasound during a health examination. Physical examination and laboratory findings were normal. The mass showed hypervascularity on enhanced computed tomography (CT), significantly increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, and slightly increased somatostatin receptor (SSTR) expression on 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT, suggesting no distant metastases and subdiagnoses such as pancreatic PGL, NET, or primary tumor. Intraoperative pathology suggested lymphatic hyperplasia, and only simple tumor resection was performed. The patient was diagnosed with the hyaline vascular variant of CD, which was confirmed by postoperative immunohistochemistry. The patient was discharged successfully, and no recurrence was observed on regular review.

High glucose uptake and slightly elevated SSTR expression are potentially new diagnostic features of CD of the pancreas.

Core tip: Some rare tumors with high blood supply to the pancreas, such as Castleman disease (CD), paraganglioma, and neuroendocrine tumors are difficult for clinicians to differentially diagnose based on conventional imaging and clinical presentation. In our case, CD of the pancreas had no obvious clinical features as previously reported but showed higher glucose uptake and mildly increased somatostatin receptor expression on positron emission tomography/computed tomography, which might help in the diagnosis.

-

Citation: Liu SL, Luo M, Gou HX, Yang XL, He K. Castleman disease of the pancreas mimicking pancreatic malignancy on

68Ga-DOTATATE and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(5): 514-520 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i5/514.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.514

Castleman disease (CD), a rare nonclonal lymphoproliferative disorder of unknown etiology, is alternatively known as giant lymph node hyperplasia or angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia, first described by Dr. Benjamin Castleman in 1954[1]. Variably manifested and capable of influencing any region in the body, CD largely imitates both benign and malignant tumors in the neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis[2]. Despite increasing reports on CD, the condition remains difficult to diagnose, particularly when it appears as a pancreatic mass[3]. With the ability to collect structural and metabolic information, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) plays a pivotal role in the early diagnosis, robust characterization, and therapeutic evaluation of CD[4]. However, no 18F-FDG PET/CT images of pancreatic CD have thus far been reported. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT is the first choice for evaluating the well-differentiated histologic subtypes of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), but its diagnostic value for identifying CD has yet to be determined[5].

A 28-year-old woman presented to our department with the complaint of a pancreatic lesion, which was detected by ultrasound during a physical examination conducted 1 wk earlier.

The patient showed a feel-good self-report without abdominal pain, distension, diarrhea, fever, and other discomforts.

The patient had good health history.

The personal and family history of the patient was unremarkable.

The vital signs of the patient were within the normal range. No yellow staining of skin and sclera was observed. Abdominal physical examination revealed no positive signs without tenderness and lumps in the abdomen.

Blood analysis revealed mild anemia, with low hemoglobin concentration (102 g/L), normal leukocyte count, and normal platelet count. All liver function indexes were normal. The following were also normal: levels of serum amylase, lipase and alkaline phosphatase; plasma or urinary metanephrine levels; and tumor markers for alpha-fetoprotein (1.97 ng/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (3.63 ng/mL), carbohydrate antigen (CA) 153 (16.40 U/mL), and CA199 (19.66 U/mL). Endoscopic results suggested chronic nonatrophic gastritis with erosion. Fasting and postprandial insulin levels were within the normal range.

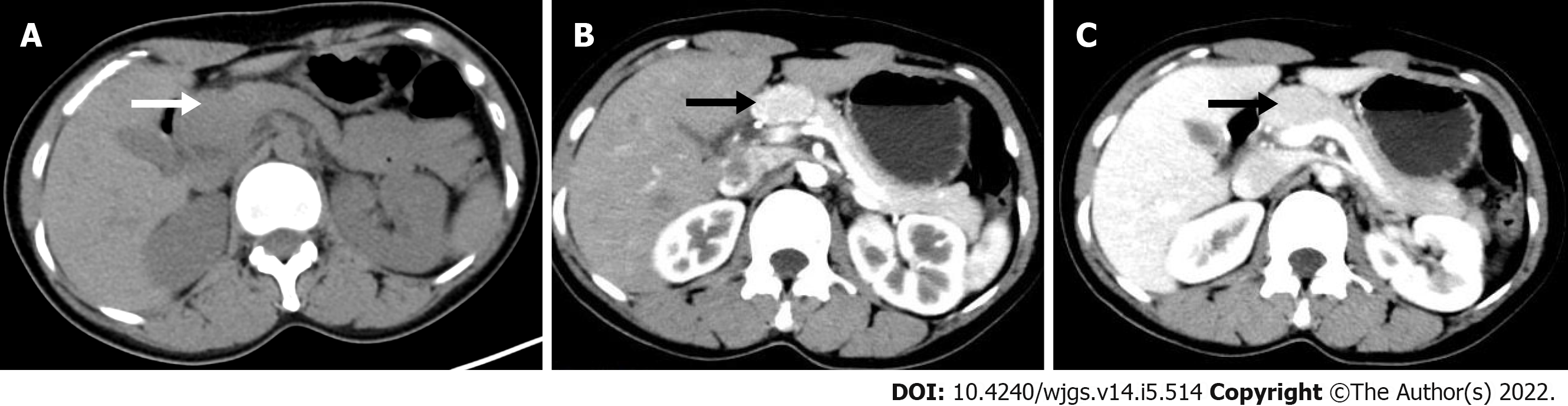

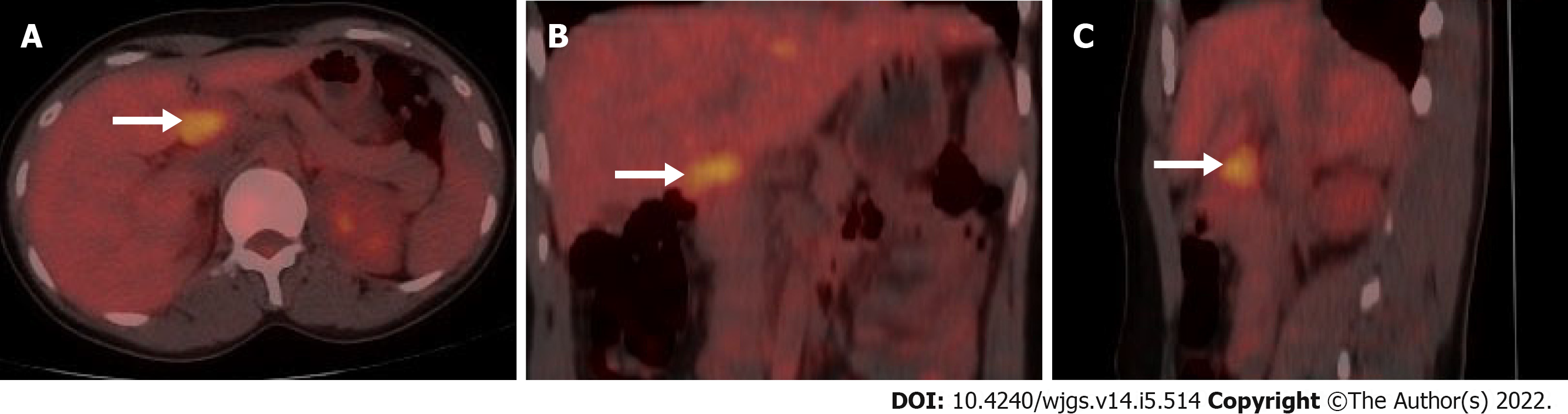

A plain CT scan (Figure 1A) showed a hyperdense lesion (arrow) measuring 3.0 cm × 2.0 cm × 2.5 cm in the neck of the pancreas. On contrast-enhanced CT, the lesion (arrow) showed significant enhancement in the arterial phase (Figure 1B), evenly distributed with smooth and well-defined boundaries, and gradually washed out in the venous phase (Figure 1C). 18F-FDG PET/CT images (Figure 2) showed glucose hypermetabolism with an standardized uptake value (SUV)max of 3.6 in the pancreatic mass.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was pancreatic hypervascular malignancy, not excluding CD, paraganglioma (PGL), and NETs.

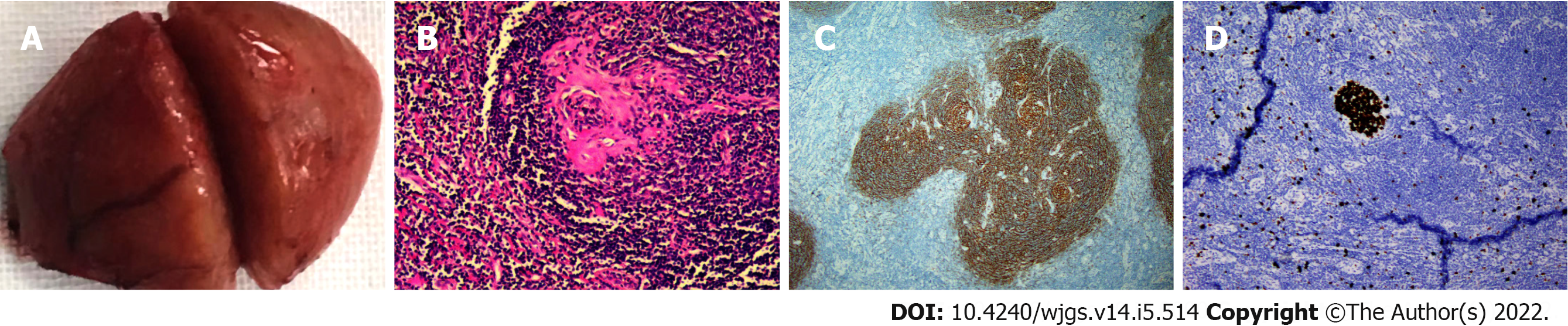

On the basis of neoplastic etiology, we intended to perform pancreaticoduodenectomy. During exploratory laparotomy, we found that the mass had a rich blood supply. We completely separated it from the pancreatic tissue. The size of the tumor was 3.5 cm × 3 cm with a complete envelope (Figure 4A). Intraoperative frozen section examination (hematoxylin–eosin staining) suggested lymphatic hyperplasia, germinal centers with regressive transformation, and expanded mantle with “an onion skin” rimming of small lymphocytes (Figure 4B). Given the high probability of a benign mass, we performed simple tumor resection.

Immunohistochemistry: CD3 and CD5 (T zone +), CD20 (B zone +), CD10 and BCL-6 (germinal center +), BCL-2 (low expression in the germinal center, high expression outside the germinal center), CD21 (Figure 4C) and CD23 (follicular dendritic cell proliferation in the germinal center), Ki-67 (Figure 4D, high expression in the germinal center, low expression outside the germinal center), and Cyclin D1(). The immunohistochemical profile was consistent with the hyaline vascular variant of CD. The patient showed no apparent discomfort after surgery and was discharged after 1 wk. No recurrence of abdominal ultrasonography was reported after half a year.

CD occurs throughout the body. Approximately 70% of the condition presents in the chest, 15% in the neck, and 15% in the abdomen–pelvis, principally involving lymphoid tissues. Castleman disease also occasionally occurs in extralymphatic sites, such as the larynx, lungs, pancreas, meninges, and muscles[6-8]. It is subclassified because of the number of enlarged lymph nodes[9]. The involvement of a single lymph node or region is referred to as unicentric CD (UCD), whereas that of multiple lymph nodes is known as multicentric CD (MCD). A battery of pathological variants includes the classic hyaline vascular type, the less common plasma cell variant and human-herpesvirus-8-associated type, and the multicentric type, not otherwise specified[10]. Moreover, 90% of the cases of hyaline vascular CD are unicentric[11]. UCD typically manifests as an asymptomatic mass with a benign growth, but MCD presents with diffuse lymphadenopathy, organ dysfunction, and systemic inflammation.

Complete removal of lymph nodes is an effective and usually curative treatment for UCD, and the recurrence rate is low. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are alternative therapies when the mass cannot be completely removed surgically[9,12]. By contrast, MCD has a poor prognosis, with a high recurrence rate associated with clinicopathological features and a high risk of malignancy leading to possible transformation into malignant lymphoma, plasmacytoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma, among others[4]. Meanwhile, treatment options for MCD are complex and include steroid therapy, chemotherapy, antiviral drugs, or the use of antiproliferative regimens[4,13]. Therefore, the clinical typing of CD determines the corresponding diagnosis and prognosis.

Conventional imaging [CT/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] is not widely used to guide typing because it fails to distinguish clearly between reactive hyperplasia and pathological enlargement of lymph nodes, nor does it sensitively detect the involvement of normal-sized lymph nodes[4]. However, 18F-FDG PET/CT can be used to assess the metabolism of lymph node enlargement. Although lymph node biopsy is the only method for the definitive diagnosis of CD, available evidence suggests that previous FDG-PET/CT can help differentiate CD subtypes and guide subsequent treatment and monitoring[13]. In our case, the 18F-FDG PET/CT results showed that the mass was solitary in the pancreas with high glucose metabolism and no distant metastases, consistent with the diagnosis of UCD. CD is rarely reported on 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT, and the ability and accuracy of its classification are unknown. In our case, UCD showed higher SSTR expression.

When the tumor is located in the pancreas and is highly vascularized, some rare conditions other than CD including PGL and NETs should also be considered[14].

PGL, a rare type of vascular NET, results from a paraganglial cell cluster that develops from the ectoderm of the neural crest[15]. The majority of the tumors are benign, and only 10% of the tumors are malignant. Although up to 77% of the tumors are commonly located retroperitoneally, the PGL is rarely located in the pancreas. A retrospective analysis of 15 cases diagnosed with PGL located in the pancreas summarized the clinical and imaging features of the disease[14]. Most patients exhibit no apparent symptoms or abdominal discomfort caused by compression. Enhanced CT suggests significant enhancement of the mass at the early stage. MR images reveal tumor isointensity for the T1-weighted image and hyperintensity, hypointensity, or mixed intensity for the T2-weighted image. PGL located in the chest and pelvis may overproduce some hormones, particularly catecholamine which causes sweating, palpitations, and hypertension. PGLs most commonly overexpress SSTR2. [68Ga]-Somatostatin agonists (SSTas) target SSTR2 and are internalized into the cells. DOTA-coupled SSTas exhibit excellent affinity for SSTR2[16]. Owing to its ultrahigh detection rate, [68Ga] DOTA-somatostatin analog PET/CT has become the preferred imaging approach to diagnosing retroperitoneal PGL[17]. However, [68Ga] SSTas PET can inevitably lead to false-positive findings, including metastatic lymph nodes owing to various cancers, meningioma, the pituitary gland, inflammatory diseases, and some rare conditions, such as fibrous dysplasia[18]. Focal pancreatic accumulation in the uncinate process may mimic pancreatic NETs.

Pancreatic NETs (pNETs) are heterogeneous epithelial neoplasms derived from pluripotent stem cells of the neuroendocrine system[19]. The tumor is malignant and classified as either functional or nonfunctional[14]. Nonfunctional pNETs are asymptomatic or manifest local compression, whereas functional pNETs cause clinical syndromes associated with hormone hypersecretion according to the cell of origin. In MRI, the tumor presents with hypointensity on T1-weighted imaging and mostly hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging; however, few are isointense or hypointense. In enhanced CT images, the functional pNET shows a clear boundary and rich blood supply, and the diameter of the tumor is generally < 2 cm[14]. The nonfunctional pNET presents heterogeneous enhancement, necrosis, and cystic degeneration in enhanced CT images and often has a larger diameter (> 5 cm) than that of the functional pNET. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT, the first choice for evaluating well-differentiated histological subtypes of NETs, provides staging with improved accuracy and additional treatment choices[20].

CD rarely occurs in the pancreas. CD of the pancreas often presents with an abundant blood supply, which, together with the lack of specificity in the clinical presentation, further blurs the distinction of the disease from NETs and PGL. PET/CT is supposed to be selected to guide the typing and subsequent treatment choices for CD. In our case, PET/CT showed that CD was solitary in the pancreas, and complete surgical resection led to a good prognosis. In addition to abundant blood supply, high glucose uptake and slightly elevated SSTR expression are potentially new diagnostic features of CD of the pancreas.

We are grateful to the patient for providing the information, support, and the written informed consent allowing us to publish their data. We thank Dr. Liu (Department of pathology, the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University) for providing pathological data.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jian X, China; Velikova TV, Bulgaria S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Castleman B, Towne VW. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital: Case No. 40231. N Engl J Med. 1954;250:1001-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bonekamp D, Horton KM, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Castleman disease: the great mimic. Radiographics. 2011;31:1793-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang Z, Jin T, Zhang X, Wu Z. Pancreatic mass found to be Castleman disease, a rare case report. Asian J Surg. 2020;43:767-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Koa B, Borja AJ, Aly M, Padmanabhan S, Tran J, Zhang V, Rojulpote C, Pierson SK, Tamakloe MA, Khor JS, Werner TJ, Fajgenbaum DC, Alavi A, Revheim ME. Emerging role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Castleman disease: a review. Insights Imaging. 2021;12:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Verçosa AFA, Flamini MEDM, Loureiro LVM, Flamini RC. 68Ga-DOTATATE and 18F-FDG in Castleman Disease. Clin Nucl Med. 2020;45:868-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Johkoh T, Müller NL, Ichikado K, Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Honda O, Tomiyama N, Naitoh H, Nakamura H, Yamamoto S. Intrathoracic multicentric Castleman disease: CT findings in 12 patients. Radiology. 1998;209:477-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Keller AR, Hochholzer L, Castleman B. Hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer. 1972;29:670-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McAdams HP, Rosado-de-Christenson M, Fishback NF, Templeton PA. Castleman disease of the thorax: radiologic features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1998;209:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mitsos S, Stamatopoulos A, Patrini D, George RS, Lawrence DR, Panagiotopoulos N. The role of surgical resection in Unicentric Castleman's disease: a systematic review. Adv Respir Med. 2018;86:36-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cronin DM, Warnke RA. Castleman disease: an update on classification and the spectrum of associated lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:236-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tey HL, Tang MB. A case of paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman's disease presenting as erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e754-e756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang X, Rao H, Xu X, Li Z, Liao B, Wu H, Li M, Tong X, Li J, Cai Q. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of Castleman disease: A multicenter study of 185 Chinese patients. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barker R, Kazmi F, Stebbing J, Ngan S, Chinn R, Nelson M, O'Doherty M, Bower M. FDG-PET/CT imaging in the management of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:648-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang W, Qin Y, Zhang H, Chen K, Liu Z, Zheng S. A rare case of retroperitoneal paraganglioma located in the neck of the pancreas: a case report and literature review. Gland Surg. 2021;10:1523-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Corssmit EP, Romijn JA. Clinical management of paragangliomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171:R231-R243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wild D, Mäcke HR, Waser B, Reubi JC, Ginj M, Rasch H, Müller-Brand J, Hofmann M. 68Ga-DOTANOC: a first compound for PET imaging with high affinity for somatostatin receptor subtypes 2 and 5. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Taïeb D, Hicks RJ, Hindié E, Guillet BA, Avram A, Ghedini P, Timmers HJ, Scott AT, Elojeimy S, Rubello D, Virgolini IJ, Fanti S, Balogova S, Pandit-Taskar N, Pacak K. European Association of Nuclear Medicine Practice Guideline/Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging Procedure Standard 2019 for radionuclide imaging of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:2112-2137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Archier A, Varoquaux A, Garrigue P, Montava M, Guerin C, Gabriel S, Beschmout E, Morange I, Fakhry N, Castinetti F, Sebag F, Barlier A, Loundou A, Guillet B, Pacak K, Taïeb D. Prospective comparison of (68)Ga-DOTATATE and (18)F-FDOPA PET/CT in patients with various pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas with emphasis on sporadic cases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1248-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A, Evans DB. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063-3072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3022] [Cited by in RCA: 3242] [Article Influence: 190.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Deroose CM, Hindié E, Kebebew E, Goichot B, Pacak K, Taïeb D, Imperiale A. Molecular Imaging of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Current Status and Future Directions. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1949-1956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |