Published online May 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.506

Peer-review started: August 31, 2021

First decision: March 11, 2022

Revised: March 23, 2022

Accepted: April 15, 2022

Article in press: April 15, 2022

Published online: May 27, 2022

Processing time: 266 Days and 18.8 Hours

Aorto-oesophageal fistula (AOF) are uncommon and exceedingly rare after corrosive ingestion. The authors report a case of AOF after corrosive ingestion that survived. A comprehensive literature review was performed to identify all cases of AOF after corrosive ingestion to determine the incidence of this condition, how it is best managed and what the outcomes are.

A previously healthy 30-year-old male, presented with a corrosive oesophageal injury after drain cleaner ingestion. He did not require acute surgical resection, but developed long-segment oesophageal stricturing, which was initially managed with cautious dilatation and later stenting. An AOF was suspected at endoscopy performed two months after the ingestion, when the patient represented with massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The fistula was confirmed on computerised tomographic angiography. The initial bleeding at endoscopy was temporised by oesophageal stenting; a second stent was placed when bleeding recurred later the same day. The stenting successfully achieved temporary bleeding control, but resulted in sudden respiratory distress, which was found to be due to left main bronchus compression caused by the overlapping oesophageal stents. Definitive bleeding control was achieved by endovascular aortic stent-grafting. A retrosternal gastroplasty was subsequently performed to achieve gastrointestinal diversion to reduce the risk of stent-graft sepsis. He was subsequently successfully discharged and remains well one year post injury.

AOF after corrosive ingestion is exceedingly rare, with a very high mortality. Most occur weeks to months after the initial corrosive ingestion. Conservative management is ill-advised.

Core Tip: Aorto-oesophageal fistula (AOF) after corrosive ingestion is exceedingly rare, but is usually catastrophic. We present a case of AOF after corrosive ingestion which was successfully managed with a combination of oesophageal stenting to achieve temporary bleeding control, and endovascular aortic stent-grafting with retrosternal gastroplasty as definitive management. Including this case, only 16 individual cases of this rare condition are found in the literature, with only two survivors prior to this case. Fistula formation usually only occurs weeks to months after the ingestion incident and as such a high level of suspicion is needed to diagnose this illusive and difficult to manage condition.

- Citation: Scriba MF, Kotze U, Naidoo N, Jonas E, Chinnery GE. Aorto-oesophageal fistula after corrosive ingestion: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(5): 506-513

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i5/506.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.506

Aorto-oesophageal fistula (AOF) is a rare, but deadly entity. Chiari’s classic triad of midthoracic pain, a herald bleed, followed by exsanguinating haemorrhage was initially described for AOF after foreign body ingestion but has since been applied to any AOF[1]. The most common causes include complicated thoracic aortic aneurysms, oesophageal foreign bodies and oesophageal carcinoma[1]. Confirming the diagnosis can be challenging and in most cases is only made at post-mortem examination. Management remains controversial and overall survival is low. AOF after corrosive or caustic ingestion are exceedingly rare and only a few cases have been described in the literature. We report a case of an AOF survivor after corrosive ingestion. A comprehensive literature review was performed to identify all cases of AOF after corrosive ingestion to assess how common the condition is, how it is best managed and what the outcomes are.

A comprehensive search of the literature up to March 31, 2021 was performed with the help of a clinical librarian in the following databases: PubMed, PubMed Central, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection and Cochrane Library. No language or time constraints were set. The following keyword search terms were used: [(Aorta OR aorta OR aortas OR aortic) AND (oesophagus OR esophagus OR oesophageal OR esophageal) AND (fistula OR fistulae OR fistulas) AND (corrosive OR corrosion OR corroding OR caustic OR caustics OR lye OR abrasive OR abrasives OR acid OR acids OR alkaline)]. The following MESH terms were also included in the search: ["Aorta" (Mesh) OR “Aortic Diseases” (Mesh)] AND [Esophageal Fistula (Mesh)] AND [“Caustics” (Mesh)] (Supplementary Table 1).

A total of 2460 studies were identified after the initial search, of which only 11 publications met the final inclusion criteria, rendering a total of 15 individual cases of AOF after corrosive ingestion (not including our own case, reported in this publication).

A 30-year-old male, known with a long-segment oesophageal stricture two months after corrosive ingestion, underwent an urgent gastroscopy for an upper gastrointestinal bleed. During the procedure he was noted to have massive bleeding from the oesophagus and an AOF was suspected.

The patient initially presented to our institution five days after accidentally consuming a corrosive substance, later identified as drain cleaner (sodium hydroxide). He was dared to consume the substance at a party and was unaware that it contained a corrosive. Except for a mild tachycardia, vital signs and routine blood work on initial admission were normal. He had an inflamed oropharyngeal mucosa and careful early upper gastrointestinal endoscopy indicated a severe corrosive injury with extensive necrosis of almost the entire oesophageal mucosa, but with viable visible underlying oesophageal muscle (Zargar grade IIb[2]). He also had a milder gastric injury, with superficial focal ulceration but no necrosis, limited to the gastric antrum (Zargar grade IIa[2]). With no features of full thickness gastric or oesophageal necrosis, an endoscopic nasojejunal feeding tube was placed and he was admitted for continued observations and nutritional support.

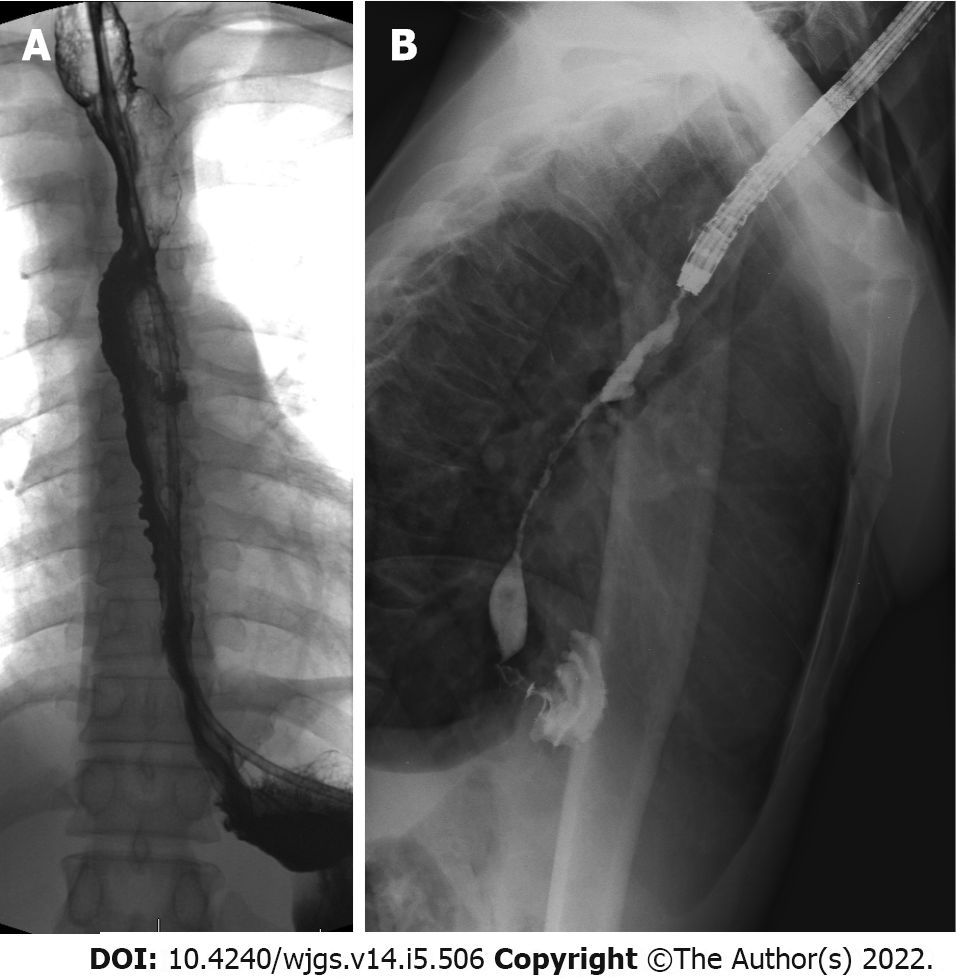

Contrast swallow examination on day nine post injury (Figure 1) confirmed the extensive oesophageal injury with irregular mucosa and already showed early long-segment stricturing. The feeding tube was removed fourteen days later after successful early cautious serial bougie dilatation to 14 mm. He was discharged home three days later tolerating a soft diet.

At his two-weekly review, he again complained of near-complete dysphagia. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with fluoroscopy now confirmed an established high-grade, long oesophageal stricture extending from 25 cm from the front incisors to the oesophagogastric junction. Due to the risk of perforation associated with pneumatic or repeat bougie dilatation, a more gradual dilatation with temporary stenting was opted for. Two overlapping 120 mm × 20 mm fully covered self-expanding metal stents were placed (Taewoong Medical Company, Gojeong, South Korea). He remained well after this, tolerating a soft diet at home.

He returned three weeks later reporting a single episode of haematemesis, but was haemodynamically and generally well. He did not complain of dysphagia. Gastroscopy was again performed, which revealed both stents in-situ and patent. However, the most proximal stent had migrated distally by some 2 cm with an area of stricturing above this. The scope was passed beyond this with complete endoscopic examination down to the second part of the duodenum revealing no signs of gastrointestinal bleeding or pathology. On pulling back the proximal stent to cover the area of developing stricturing, brisk bleeding occurred which was controlled after placement of a third oesophageal stent.

The patient was previously healthy, with no known prior medical or surgical history.

There was no other relevant personal history or family history of note. Other than social alcohol use he denied any other substance use.

After the bleeding from the suspected AOF was temporised, his vital signs showed a blood pressure of 105/67 mmHg, a heart rate of 150 beats/minute, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/minute with oxygen saturation of 97% on room air and a normal Glascow Coma Scale of 15/15. His general examination was normal with no signs of pallor or other abnormalities.

Full blood count showed a formal haemoglobin of 9.3 g/dL and a mild leukocytosis of 11.59 × 109/L. Urea, creatinine and electrolytes were normal.

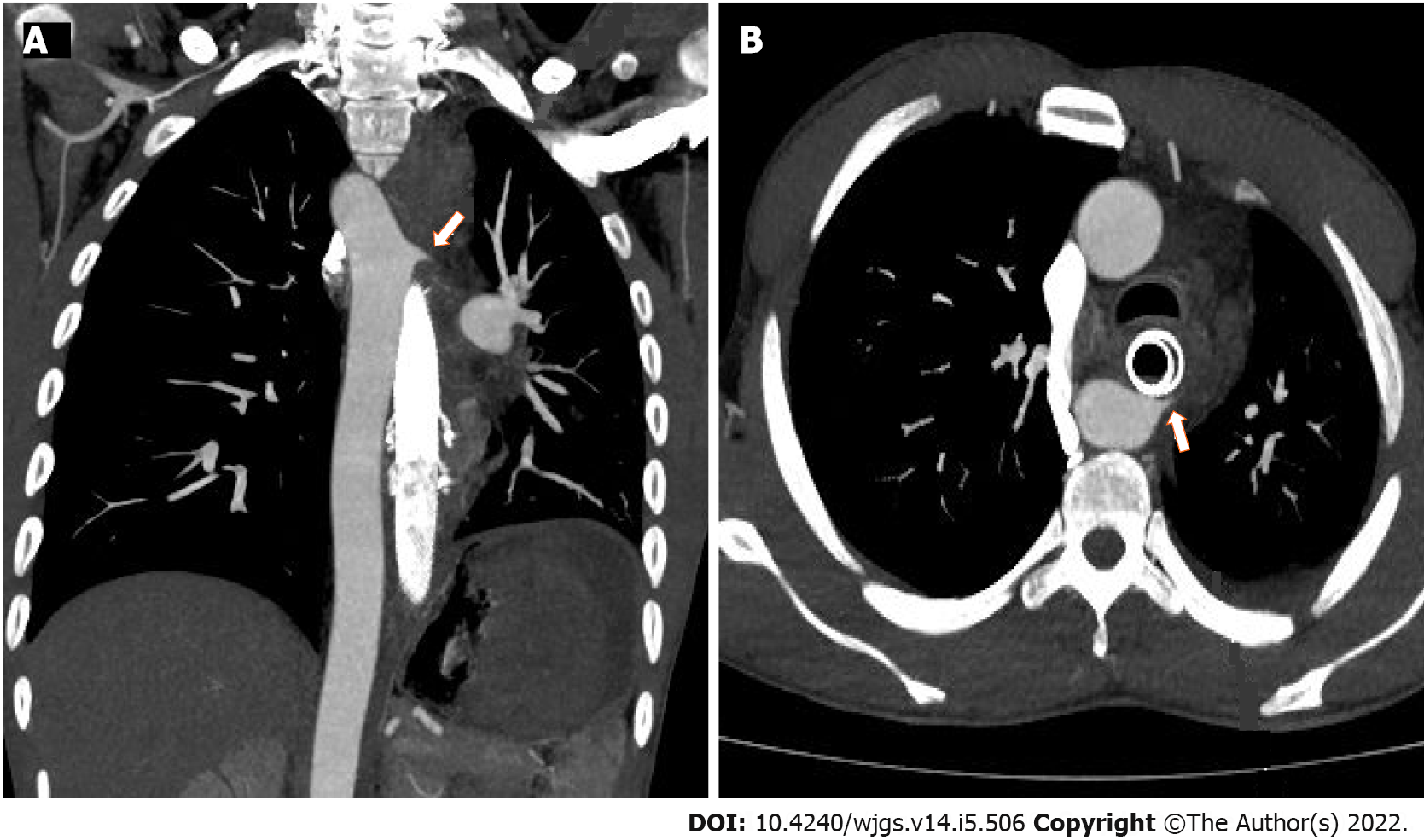

On suspicion of an AOF, an urgent computerised tomographic angiogram (CTA) was performed, which confirmed the fistula in the region of the proximal thoracic oesophagus with an aberrant right-sided aortic arch (Figure 2).

AOF after corrosive ingestion.

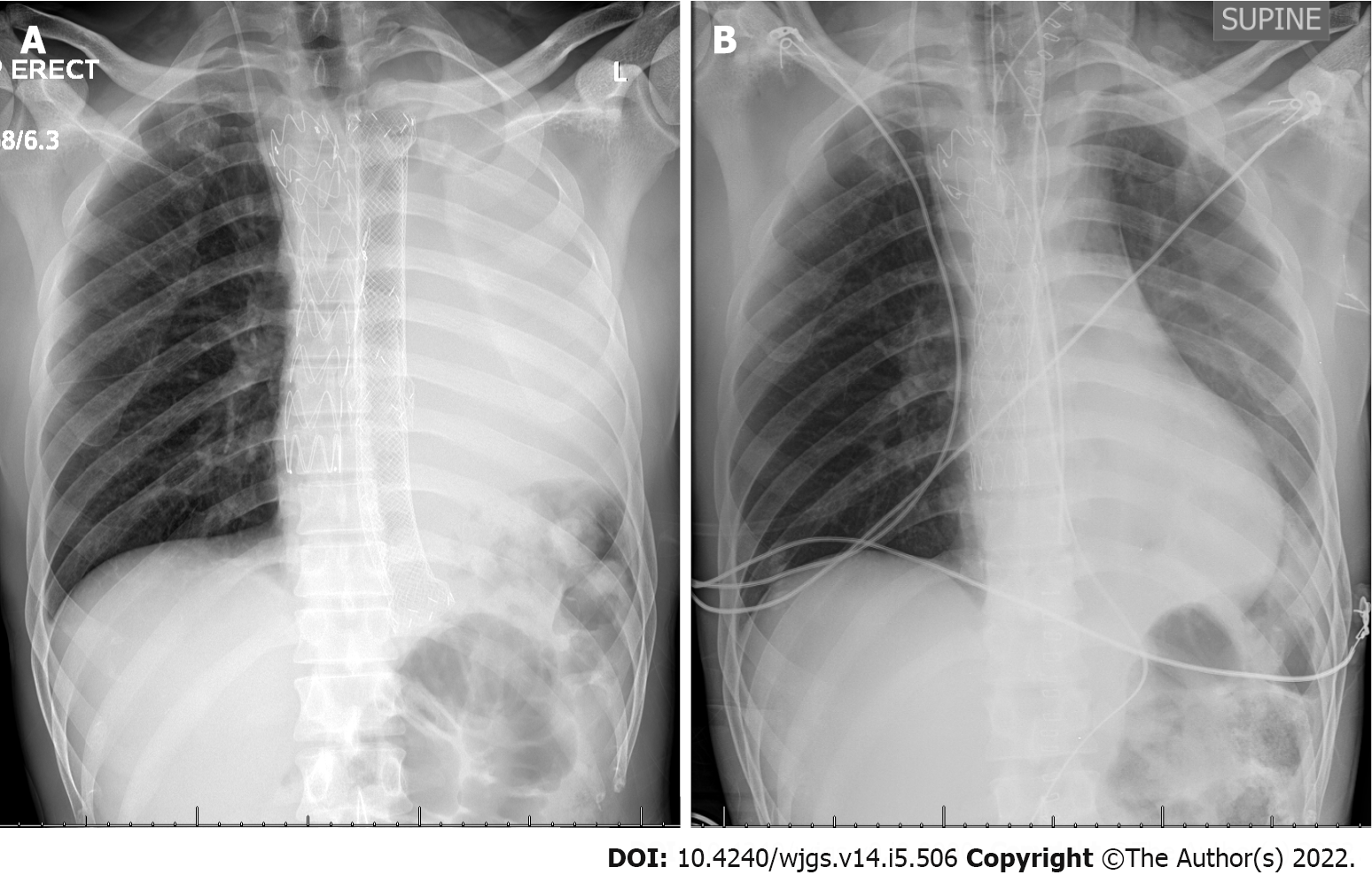

After the bleeding was stopped, the patient was resuscitated with intravenous fluids and admitted. After CTA confirmation of the AOF, an endovascular aortic repair was planned but another massive bleed occurred which was temporised with a fourth oesophageal stent. This was followed by transient respiratory distress and chest X-ray showed a near-complete “white-out” of the left chest (Figure 3). A thoracic endovascular aortic repair via a right femoral approach using a 28 mm (proximal diameter) × 28 mm (distal diameter) × 157 mm (covered length) Valiant thoracic stent graft (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) was then successfully performed.

To prevent endovascular stent contamination, an oesophageal exclusion with a retrosternal gastric conduit was performed five days after the endovascular procedure. On-table bronchoscopy showed extrinsic compression with near-complete occlusion of the left main bronchus. On-table oesophagoscopy with successful retrieval of the four oesophageal stents was performed. Repeat bronchoscopy now revealed a patent left main bronchus, confirming that the extrinsic bronchial occlusion was due to the radial pressure of the oesophageal stents. The oesophageal exclusion was then performed, leaving the native, severely strictured and adherent oesophagus in-situ.

The patient was discharged 13 d later without complication. He subsequently developed mild stricturing of the proximal oesophagogastric anastomosis, which was successfully treated with serial dilatations. At one year post the initial corrosive injury the patient is well and dysphagia-free.

AOF are uncommon. In an extensive literature review in 1991 Hollander and Quick[1] identified a total of only 500 AOF cases of all aetiologies, with 51% being related to thoracic aortic aneurysms, 19% related to foreign body ingestion and 17% related to oesophageal malignancy[1]. Aorta-oesophageal fistula after corrosive ingestion is exceedingly rare. Our own comprehensive literature review on AOF after corrosive ingestion yielded only 15 cases other than our own, with only two other reported survivors. Table 1 outlines numerous characteristics of the entire cohort of 16 cases. Unfortunately, as most cases pre-date 2000, missing data was common in many cases. In the 13 cases where the mode of diagnoses was specified, the diagnosis was only made on imaging in two patients, at surgical exploration in two patients and in the remaining nine at post-mortem examination. The time from corrosive ingestion to AOF formation ranged from 2–62 d, with a median time of 14 d (IQR: 11.5–35.5 d). In only four cases (25%) was a herald bleed prior to massive haemorrhage reported. Five cases had a concomitant fistula between the oesophagus and respiratory tract (four tracheo-oesophageal fistulae and one broncho-oesophageal fistula), while in seven cases a concomitant gastric injury was described. Of the 16 described cases, 13 died resulting in a mortality rate of 81.2%. In four patients (25%) management of the AOF was attempted, of whom three survived.

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Sex | Corrosive agent | Ingestion intent | Days to presentation | Herald bleed | Diagnosis | Management of AOF | Outcome | Associated corrosive injuries |

| Schranz[9], 1934 | 16 | F | Alkali | 1 | 7 | N | Autopsy | - | D | BOF |

| Singh et al[10], 1976 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Autopsy | - | D | - |

| Waller and Rumler[11], 1963 | 10 | M | Alkali | A | 10 | N | Autopsy | - | D | TOF, gastric (necrosis) |

| Rabinovitz et al[12], 1990 | 23 | F | 1 | 1 | 12 | Y | Autopsy | - | D | TOF, gastric and duodenal injuries |

| Singh et al[10], 1976 | 54 | M | Alkali | 1 | 27 | N | Autopsy | - | D | TOF, diaphragm (necrosis, perforation) |

| Ottosson[13], 1981 | 14 | M | Alkali | A | 44 | N | Surgery | Primary repair of the oesophagus and aorta | D | - |

| Sarfati et al[14], 1987 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | D | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | D | 1 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | D | 1 | |

| Rabinovitz et al[12], 1990 | 34 | M | Alkali | S | 23 | Y | Autopsy | - | D | TOF, gastric (necrosis with perforation) |

| Marone et al[7], 2006 | 20 | M | Acid | S | 25 | N | Surgery | Open local aortic repair, then endovascular stent repair. Oesophageal bypass (colon conduit) | S | Gastric necrosis with perforation |

| Yegane et al[15], 2008 | 37 | M | Acid | S | 11 | N | Autopsy | - | D | - |

| 40 | M | Acid | 1 | 2 | N | Autopsy | - | D | - | |

| 67 | M | Acid | 1 | 60 | Y | Autopsy | - | D | Gastric (di Constanzo grade II injury) | |

| Lee et al[8], 2011 | 75 | F | Alkali | 1 | 60 | N | CT | Open aortic repair, total oesophago-gastrectomy | S | Gastric (total gastrectomy) |

| This study2 | 30 | M | Alkali | A | 62 | Y | CT, Endoscopy | Oesophageal stenting endovascular aortic repair, oesophageal bypass (gastric conduit) | S | Gastric (Zargar IIa injury) |

Diagnosis remains challenging. Chiari’s triad is of limited diagnostic value with only a minority of patients in this review having evidence of a herald bleed. Although endoscopy may be useful in suspecting the injury, vascular imaging with angiography or CTA is required to make a definitive diagnosis. Fistulae following corrosive ingestion typically occur more than two weeks post injury. In the context of the case reported the significant radial force exerted by self-expanding oesophageal stents needs to be considered. We postulate that the AOF likely formed due to a combination of factors, including the initial corrosive injury, but cannot exclude that the radial force of the stents placed was contributory. This force was also responsible for bronchial compression, which has previously been described in the literature[3,4]. It needs to be highlighted that using oesophageal stenting in the early management of the corrosive stricture is controversial, but was made by the treating team in light of the severity and length of the corrosive stricture where the risk of perforation using bougie or balloon dilatation was considered too high. Using an oesophageal stent to temporise bleeding was performed as the patient was present in the endoscopy suite where fluoroscopy was readily available, but using balloon tamponade to achieve haemostasis is another option and may be more suitable in other settings.

Conservative management of AOF is invariably fatal and should be reserved for patients not fit for intervention. Effective management of any AOF requires management of the fistula from both the oesophageal and aortic sides. The decision between open and endovascular management of the aorta is controversial and although contemporary guidelines consider open repair the gold standard, this is mostly based on fistulae secondary to thoracic aortic aneurysms, where the primary pathology is vascular[5]. With corrosive ingestion the primary pathology is in the oesophagus. Attempted definitive repair using an endovascular stent-graft leaves the significant concern of oesophageal content gaining access to the synthetic graft via the fistula, with the risk of prosthetic sepsis. For this reason, management of the fistula from the oesophageal side is mandatory. Although oesophageal stenting could facilitate temporizing the bleeding and divert content away from the fistula, long-term results in terms of preventing graft infection are lacking. While a surgical conduit will effectively divert luminal content, leaving the native oesophagus in-situ is associated with a risk of mucocoele formation and possible future risk of malignant transformation[6]. However, this must be weighed up against a difficult oesophageal resection due to extensive mediastinal fibrosis with a high risk of associated surgical morbidity[6].

The patient described in this case report was managed with minimally invasive interventions for temporizing control using oesophageal stenting and definitive management of the aortic defect with endovascular stenting. Surgical management was reserved for the oesophageal reconstruction. Marone et al[7] reported the first successfully managed patient with AOF after corrosive, which involved initial local closure of the fistula via open surgical access followed by endovascular stent repair of the aorta and oesophageal replacement with a retrosternal colonic conduit. Lee et al[8] reported a patient that was successfully managed with surgical repair of the aorta, followed by oesophagogastrectomy.

In view of the extreme rarity of this condition, with only five other cases described in the last 30 years, creating evidence-based management algorithms or follow-up protocols is truly challenging. We do however advise clinicians treating patients after corrosive ingestion to ensure there is regular, planned patient follow-up in all those who sustain significant oesophageal corrosive injuries (Zargar IIb and above) who survive the initial management period. This should be done primarily due to the very high incidence of subsequent stricture formation frequently requiring long term endoscopic treatment. The common scenario of multi-level or long-segment stricturing seen with severe corrosive injuries poses challenging management problems[6]. Clinicians should be alerted to the fact that any reported gastro-intestinal bleeding in these patients, even months after the initial injury, may represent an AOF. We recommend CT angiography as the diagnostic modality of choice and strongly advocate that all diagnosed fistulae be treated on an individualised basis in a multi-disciplinary environment via combined approaches from the vascular and gastro-intestinal sides of the fistula.

Outcomes for AOF after corrosive ingestion remain dismal. Although a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, it should be considered as a cause following corrosive injury and requires a high level of suspicion as fistula formation often occurs in a delayed fashion after the ingestion event. Management should be individualised as guidelines to aid decision-making are lacking. Optimal outcomes are best achieved with multimodality therapy in a multidisciplinary setting.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chanel Robinson (PhD) for providing formal biostatistical support and in revising parts of the paper.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Africa

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chiu CC, Taiwan; Lim KT, Singapore; Link A, Germany S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Hollander JE, Quick G. Aortoesophageal fistula: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Med. 1991;91:279-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Nagi B, Mehta S, Mehta SK. Ingestion of corrosive acids. Spectrum of injury to upper gastrointestinal tract and natural history. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:702-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Farivar AS, Vallières E, Kowdley KV, Wood DE, Mulligan MS. Airway obstruction complicating esophageal stent placement in two post-pneumonectomy patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:e22-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aneeshkumar S, Sundararajan L, Santosham R, Palaniappan R, Dhus U. Erosion of esophageal stent into left main bronchus causing airway compromise. Lung India. 2017;34:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chakfé N, Diener H, Lejay A, Assadian O, Berard X, Caillon J, Fourneau I, Glaudemans AWJM, Koncar I, Lindholt J, Melissano G, Saleem BR, Senneville E, Slart RHJA, Szeberin Z, Venermo M, Vermassen F, Wyss TR; Esvs Guidelines Committee; de Borst GJ, Bastos Gonçalves F, Kakkos SK, Kolh P, Tulamo R, Vega de Ceniga M, Document Reviewers, von Allmen RS, van den Berg JC, Debus ES, Koelemay MJW, Linares-Palomino JP, Moneta GL, Ricco JB, Wanhainen A. Editor's Choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Vascular Graft and Endograft Infections. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;59:339-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 66.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chirica M, Bonavina L, Kelly MD, Sarfati E, Cattan P. Caustic ingestion. Lancet. 2017;389:2041-2052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marone EM, Baccari P, Brioschi C, Tshomba Y, Staudacher C, Chiesa R. Surgical and endovascular treatment of secondary aortoesophageal fistula. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:1409-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee YH, Han HY. CT Findings of an Aortoesophageal Fistula due to Lye Ingestion: A Case Report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2011;64:553. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Schranz D. Ueber eigenartige Faelle von Laugenaetzung. Dtsch Z Gesamte Gerichtl Med. 1934;23:152-159. |

| 10. | Singh AK, Kothawla LK, Karlson KE. Tracheoesophageal and aortoesophageal fistulae complicating corrosive esophagitis. Chest. 1976;70:549-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Waller H, Rumler W. Ueber den ungewoehnlichen Ausgang einer Laugenveraetzung. Med Klin. 1963;58:1719-1721. |

| 12. | Rabinovitz M, Udekwu AO, Campbell WL, Kumar S, Razack A, Van Thiel DH. Tracheoesophageal-aortic fistula complicating lye ingestion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:868-871. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ottosson A. Late aortic rupture after lye ingestion. Arch Toxicol. 1981;47:59-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sarfati E, Gossot D, Assens P, Celerier M. Management of caustic ingestion in adults. Br J Surg. 1987;74:146-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yegane RA, Bashtar R, Bashashati M. Aortoesophageal fistula due to caustic ingestion. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |