Published online May 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.470

Peer-review started: November 6, 2021

First decision: January 9, 2022

Revised: January 18, 2022

Accepted: April 9, 2022

Article in press: April 9, 2022

Published online: May 27, 2022

Processing time: 199 Days and 18 Hours

Cholecystectomy is the preferred treatment option for symptomatic gallstones. However, another option is gallbladder-preserving cholecystolithotomy which preserves the normal physiological functions of the gallbladder in patients desiring to avoid surgical resection.

To compare the feasibility, safety and effectiveness of pure natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) gallbladder-preserving cholecystolithotomy vs laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) for symptomatic gallstones.

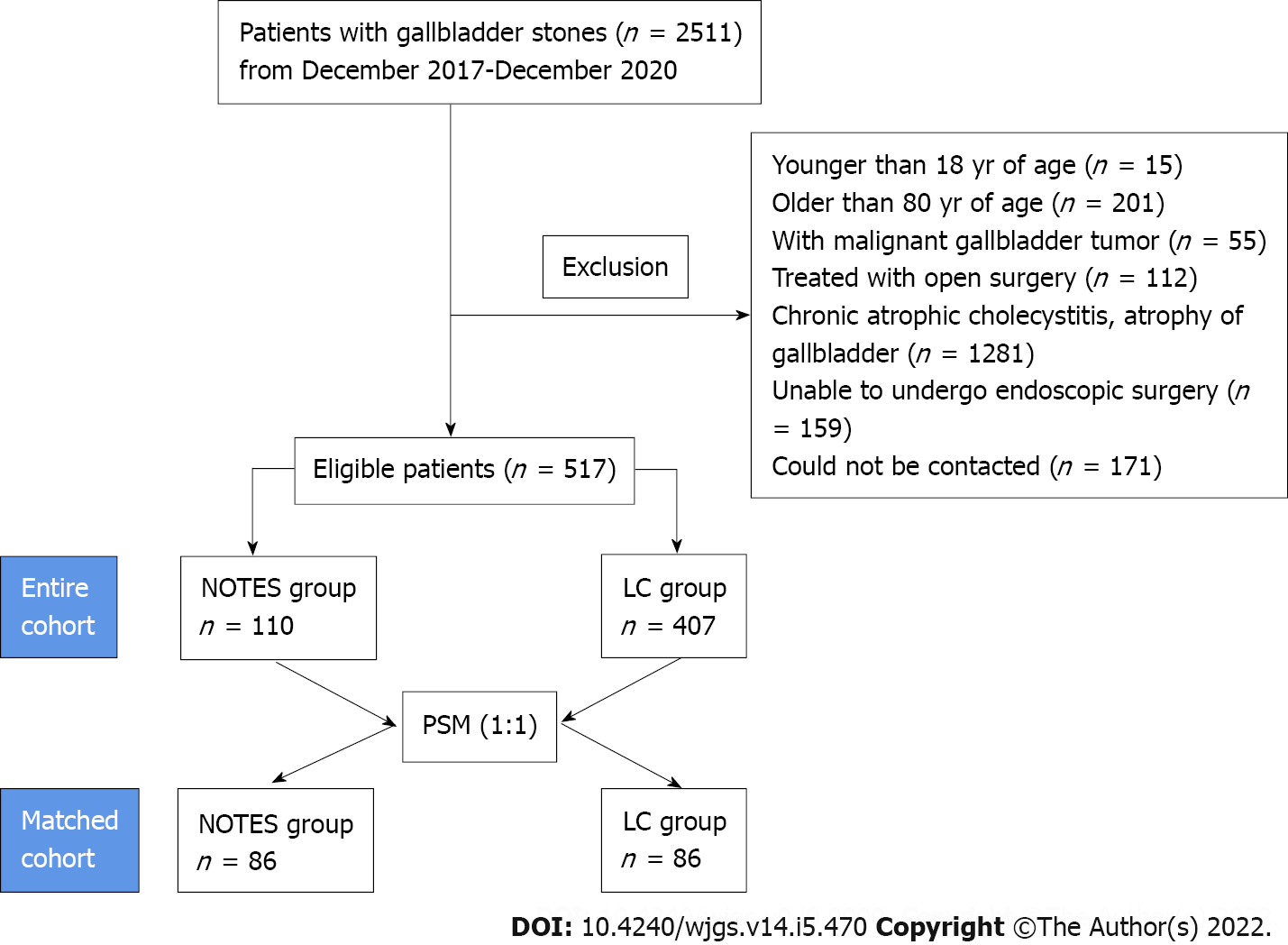

We adopted propensity score matching (1:1) to compare trans-rectal NOTES cholecystolithotomy and LC patients with symptomatic gallstones. We reviewed 2511 patients with symptomatic gallstones from December 2017 to December 2020; 517 patients met the matching criteria (NOTES, 110; LC, 407), yielding 86 pairs.

The technical success rate for the NOTES group was 98.9% vs 100% for the LC group. The median procedure time was 119 min [interquartile ranges (IQRs), 95-175] with NOTES vs 60 min (IQRs, 48-90) with LC (P < 0.001). The frequency of post-operative pain was similar between NOTES and LC: 4.7% (4/85) vs 5.8% (5/95) (P = 0.740). The median duration of post-procedure fasting with NOTES was 1 d (IQRs, 1-2) vs 2 d with LC (IQRs, 1-3) (P < 0.001). The median post-operative hospital stay for NOTES was 4 d (IQRs, 3-6) vs 4 d for LC (IQRs, 3-5), (P = 0.092). During follow-up, diarrhea was significantly less with NOTES (5.8%) compared to LC (18.6%) (P = 0.011). Gallstones and cholecystitis recurrence within a median of 12 mo (range: 6-40 mo) following NOTES was 10.5% and 3.5%, respectively. Concerns regarding the presence of abdominal wall scars were present in 17.4% (n = 15/86) of patients following LC (mainly women).

NOTES provides a feasible new alternative scar-free treatment for patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo cholecystectomy. This minimally invasive organ-sparing procedure both removes the gallstones and preserves the physiological function of the gallbladder. Reducing gallstone recurrence is essential to achieving widespread clinical adoption of NOTES.

Core Tip: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the current gold standard for treating gallstones. However, long-term complications of LC such as duodenogastric reflux, post-cholecystectomy syndrome, bile duct injuries and an increase in colonic cancer remain largely unreported/unstudied. Some experts now advocate simple gallstone extraction with gallbladder preservation (cholecystolithotomy) in order to avoid post-cholecystectomy syndrome, bile duct injury, and its association with colon cancer. The authors’ developed the pure natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery trans-rectal gallbladder preserving cholecystolithotomy technique for removal of gallbladder stones. This study compared trans-rectal gallbladder preserving cholecystolithotomy with traditional LC.

- Citation: Ullah S, Yang BH, Liu D, Lu XY, Liu ZZ, Zhao LX, Zhang JY, Liu BR. Are laparoscopic cholecystectomy and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery gallbladder preserving cholecystolithotomy truly comparable? A propensity matched study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(5): 470-481

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i5/470.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i5.470

Approximately 25 million people in the United States have gallstones, resulting in more than one million hospitalizations each year[1-4]. Cholecystectomy is the gold standard treatment for symptomatic gallstones[5]. For the past three decades, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has been the treatment of choice[6-8] as it is minimally invasive. However, since Rao et al[9]’s description of the first human NOTES trans-gastric appendectomy in 2004, ultra-minimally invasive techniques have evolved including natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) cholecystectomy[9]. Some experts now advocate cholecystolithotomy without gallbladder excision in order to preserve gallbladder function and to avoid gallbladder resection-related complications[10-13]. In addition, cholecystectomy is associated with post-cholecystectomy syndrome, surgical incision complications, and bile duct injury[14-16]. The reasons given for gallbladder preservation include the reported associations of colon cancer, functional gastrointestinal and psychological conditions following cholecystectomy[15-17].

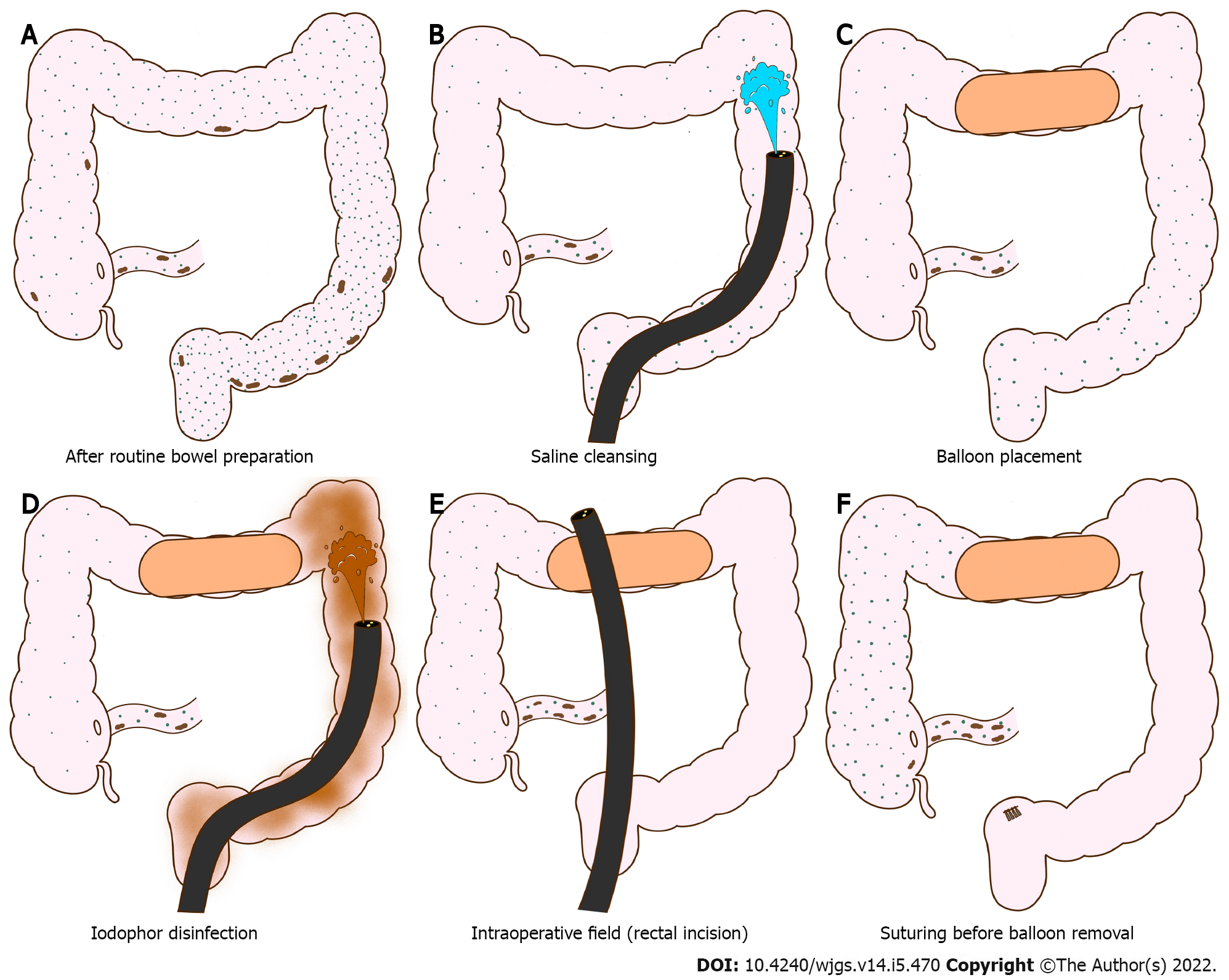

Experimental studies using flexible endoscopic trans-rectal NOTES have suggested this approach as an attractive alternative option for intra-abdominal procedures[18-21]. However, concern regarding peritoneal contamination with trans-rectal NOTES limited the adoption of trans-rectal NOTES as a routine clinical practice. The problem of peritoneal contamination during trans-rectal NOTES has now been largely overcome with the use of a detachable obstructive colonic balloon which prevents distal colonic contamination (Figure 1)[22-24].

No comparison of NOTES and LC for symptomatic gallstones has previously been reported. Therefore, we performed a comparative study of pure NOTES gallbladder preservation cholecystolithotomy and LC to examine relative effectiveness as well as differences in post-operative pain, infection, time to normal diet intake, hospital duration, short- and long-term complications.

The study protocol was approved by the independent ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin University. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedure. All NOTES procedures were performed by an expert gastroenterologist with experience of more than 150 NOTES procedures. The research was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All authors had access to the study data, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

We extracted patient data from the inpatient database of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University who were treated for gallbladder disease from December 2017 to December 2020. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients over the age of 18 years and less than 80 years of age; (2) Patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis confirmed by B-ultrasound or other imaging examination (CT/MRI); (3) Patients with no history of major upper abdominal surgery; (4) A strong desire by the patient to retain the gallbladder; and (5) No absolute surgical contraindications, including severe hepatic, renal, cardiac and pulmonary insufficiency, history of cerebral coma and allergy to anesthesia etc. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Patients younger than 18 years or older than 80 years of age; (2) Patients with acute cholecystitis, chronic atrophic cholecystitis, atrophy of the gallbladder due to any reason and suspicion of gallbladder cancer; (3) Unable to undergo endoscopic surgery for various reasons such as associated other diseases or age factor; and (4) Could not be contacted or loss of information.

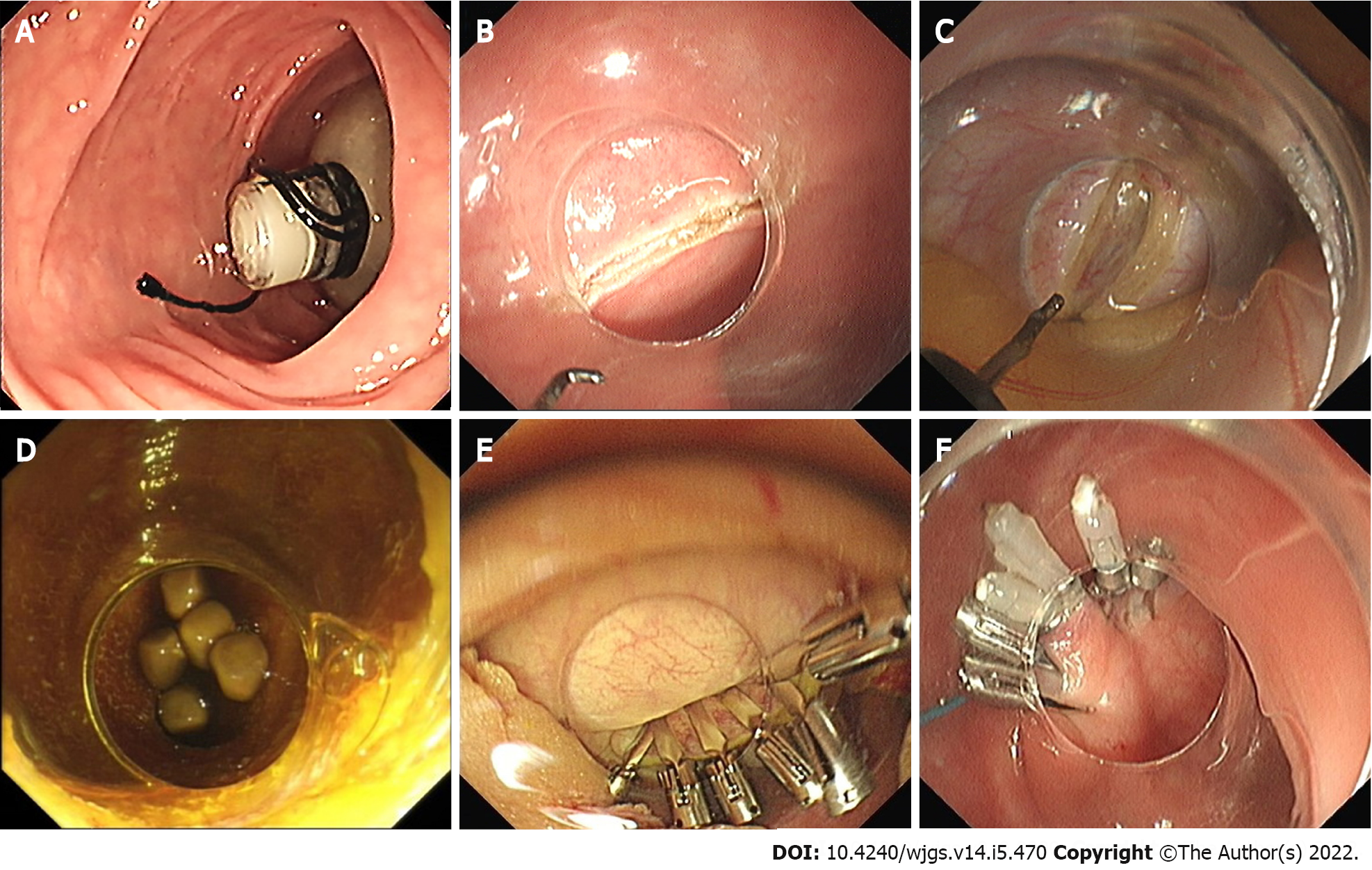

Description of trans-rectal NOTES technique: After routine bowel preparation, all procedures were performed under general anesthesia. With the patients in the lithotomy position, a colonoscope (EVIS GIF-Q260J, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced into the transverse colon for colonic cleansing. A detachable colonic exclusion balloon was placed into the transverse colon with help of the colonoscope and inflated to 3.0-3.5 cm in diameter by injecting 120 to 140 mL of air into the balloon to occlude the transverse colonic lumen (Figure 2A). Cleansing and disinfection of the distal colonic and rectal lumen was then completed with a 0.1% povidone-iodine solution. A disinfected (a low temperature ethylene oxide processed) gastroscope with a transparent cap attached to the tip of the endoscope was inserted and an incision was made on the right anterior wall of the rectum 15 to 20 cm from the anal verge using Hook and IT knives (Figure 2B). The endoscope was advanced upward through the inter-bowel space into the upper peritoneal cavity where the liver and gallbladder were identified. A full-thickness longitudinal incision was created in the gallbladder wall using the Hook and IT knifes (Figure 2C). The tip of the endoscope was inserted into the gallbladder cavity and the bile was aspirated. The lumen was then cleansed with normal saline and the gallstones were extracted from the gallbladder using a biliary stone extractor (E151186, GMBH FLEX, Germany) and removed via the trans-rectal incision (Figure 2D). The gallbladder incision was closed with endoclips (longclip, HX-610-090, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 2E). The endoscope was then withdrawn and the stomal opening in the rectum was closed with endoclips and endoloops (HX-20L-1, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 2F). The colon occlusion balloon was deflated and removed and the colonic mucosa at the site of balloon occlusion was inspected (Videos 1 and 2 ).

Description of laparoscopic technique: LC was performed by expert gastroenterology surgeons with experience of more than 500 cholecystectomies. LC was performed using a standard laparoscopic approach.

The two methods of therapy were compared with regard to treatment success, procedure time, post-operative pain, time to normal diet intake, duration of hospital stay, and post-operative short- and long-term complications, and recurrence rate.

The median follow-up period was one year (range: 6-40 mo). The primary outcome was treatment success. In the NOTES-treated group, treatment success was defined as successful if the procedure was completed using endoscopic surgery without conversion to laparoscopic or open surgery. In the LC group, treatment success was identified as a successful cholecystectomy without converting to open surgery.

Secondary outcomes included procedure time, post-operative pain, duration of post-operative hospital stay, duration of fasting, and post-operative short-term (within 2 wk) and long-term complications, and recurrence rate. In the NOTES group, short-term complications included biliary peritonitis, fever, nausea and vomiting, bleeding and systemic complications (pulmonary embolism, stroke, cardiac events, acute renal failure, and sepsis). Long-term complications included recurrent gallstone, recurrent cholecystitis, diarrhea, constipation, and malignant tumors of the gallbladder. In the LC group, short-term complications included incisional infection, incisional pain, bile duct injury, anesthesia-related complications, and systemic complications. Long-term complications included abdominal pain, hernia, and digestive symptoms. All enrolled patients were followed up by telephone and/or medical records.

We used logistic regression models for the calculation of propensity scores. We used a 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) with the NOTES and LC groups and the caliper value fixed at 0.1 for the propensity matching score. The study matched clinical baseline indicators including age, sex, bilirubin levels, gallbladder stones, temperature, white blood cell count, and hemoglobin. An absolute standard difference of less than 0.1 was considered negligible between both groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentages with 95%CI, and continuous variables (operative time, post-operative hospital stay, fasting time, and recurrent time) were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). The Pearson × 2 and Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was applied for continuous variables. Gender, age, baseline leukocytes, total bilirubin, and number of gallbladder stones were analyzed by univariate Cox proportional risk regression for the 1-year recurrence-free outcome. PSM and all calculations were conducted with Stata/SE 15.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, United States). A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We extracted data from 2511 patients from the inpatient database of patients treated for gallbladder disease. We excluded 15 patients younger than 18 years of age, 201 patients older than 80 years of age, 55 patients with malignant gallbladder tumor, 112 patients with open surgery, 1281 patients with chronic atrophic cholecystitis and/or atrophy of the gallbladder, 159 patients unable to undergo endoscopic surgery, and 171 patients who could not be contacted (lost to follow-up). Consequently, there were 517 patients eligible for matching (NOTES, 110; LC, 407), and yielded 86 patient pairs (Figure 3). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients before and after PSM.

| Variable | NOTES group (n = 86) | LA group (n = 86) | P value |

| Age, n (%) | 0.88 | ||

| ≤ 60 yr | 51 (59.3) | 50 (58.1) | |

| > 60 yr | 35 (40.7) | 36 (41.2) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.53 | ||

| Male | 55 (63.9) | 51 (59.3) | |

| Female | 31 (36.1) | 35 (40.7) | |

| Total bilirubin levels1, n (%) | 0.72 | ||

| 0-25 | 83 (96.5) | 81 (94.2) | |

| > 25 | 3 (3.5) | 5 (5.8) | |

| Temperature2, n (%) | 0.75 | ||

| ≤ 37.2℃ | 6 (6.9) | 5 (5.8) | |

| > 37.2℃ | 80 (93.1) | 81 (94.2) | |

| Gallbladder stones, n (%) | 0.75 | ||

| ≤ 3 | 6 (6.9) | 5 (5.8) | |

| > 3 (or Mud-like gallstones) | 80 (93.1) | 81 (94.2) |

In the NOTES group, one patient (n = 85/86) was referred to open surgery for removal of the gallbladder due to adhesions between the gallbladder and surrounding tissue. The overall success rate was 98.9% (95%CI: 94.3%-99.8%; n = 85/86). All the patients in the LC group successfully underwent LC with a success rate of 100%. Subsequent pathology confirmed chronic cholecystitis in all. The median operative time was 119 min (IQRs, 95-175) in the NOTES group which was longer than the LC group with a median time of 60 min (IQRs, 48-90), (difference, 59 min; P < 0.001). The median duration of fasting in the NOTES group was 1 d (IQRs, 1-2) vs 2 d (IQRs, 1-3) in the LC group, (difference, 1 d; P < 0.001). The median post-operative hospital stay was 4 d (IQRs, 3-6) in the NOTES group vs 4 d in the LC group (IQRs, 3-5), (P = 0.092).

In the NOTES group, 2.3% (95%CI: 0.6%-8.9%; n = 2/85) of patients developed post-operative biliary peritonitis. All the peritonitis patients recovered with abdominal irrigation (percutaneous flushing of the peritoneal cavity with saline solution) and combined antibiotic treatment. In the LC group, 2.3% (95%CI: 0.6%-7.4%; n = 2/86) of patients developed lung infections, 5.8% (95%CI: 2.3%-11.7%; n = 5/86) of patients had severe abdominal pain, 1 (1%, 95%CI: 0.2%-5.7%) patient had a wound infection with fever, and one patient had urinary retention. The mortality rate in both groups was 0%.

During the follow-up period, all patients in the two groups are alive. In the LC group, 18.6% (95%CI: 10.6%-25.6%; n = 16/86) of patients developed diarrhea, of which 8 (8.4%, 95%CI: 4.3%-15.7%) had frequent diarrhea, 5 (5.3%, 95%CI: 2.3%-11.7%) patients were prone to diarrhea after eating fatty foods, 3 (3.3%, 95%CI: 1.1%-8.9%) patients had occasional diarrhea, and diarrhea symptoms were not relieved by symptomatic treatment. In comparison, 5.8% (95%CI: 2.3%-11.8%; n = 5/85) of NOTES patients presented with diarrhea, 3 of them after undergoing cholecystectomy which was significantly less frequent than after LC [difference, 11.5 percentage points (95%CI: 2.5-20.8); P = 0.011]. 2.3% (95%CI: 0.6%-7.4%; n = 2/85) of NOTES patients presented with constipation vs 3.5% (95%CI: 1.1%-8.9%; n = 3/86) of LC patients [difference, 1.03 percentage points (95%CI: -0.5-7); P = 0.663].

In the LC group, 5.8% (95%CI: 2.3%-11.7%; n = 5/86) of patients had pain in the surgical area with anxiety; 17.4% (95%CI: 9.8%-24.4%; n = 15/86) of patients were concerned about scars on the abdominal wall (mainly women). 11.6% (95%CI: 5.8%-18.3%; n = 10/86) of patients had decreased appetite and reduced their diet compared to their preoperative status. Only 2.3% (n = 2/85) of NOTES patients had decreased appetite [difference, 8.4 percentage points (95%CI: 1.3-16.3); P = 0.018]. Two (2.3%, 95%CI: 0.6%-7.4%) patients had back pain after exertion, and one (1.06%, 95%CI: 0.2%-5.7%) patient had chest tightness. One (1.06%, 95%CI: 0.2%-5.7%) patient developed renal calculi (Table 2).

| NOTES group, n (%), (95%Cl) | Laparoscopic group, n (%), (95%Cl) | Differences | |

| Short-term complications | |||

| Biliary peritonitis | 2 (2.3), 0.6-8.9 | 0 (0), - | < 0.497 |

| Post-operative pain (Abdominal or incisional) | 4 (4.7), 1.8-11.4 | 5 (5.8), 2.5-12.9 | 0.740 |

| Lung infection | 0 (0), - | 2 (2.3), 0.6-9.9 | |

| Incisional infection | 0 (0), - | 1 (1.2), 0.2-6.3 | |

| Urinary retention | 0 (0), - | 1 (1.2), 0.2-6.3 | |

| Long-term complications | |||

| Diarrhea | 5 (5.8), 2.5-12.9 | 16 (18.6), 11.8-28.1 | 0.011 |

| Constipation | 2 (2.3), 0.6-8.9 | 3 (3.5), 1.2-9.8 | 0.063 |

| Decreased appetite | 2 (2.3), 0.6-8.9 | 10 (11.6), 6.4-20.1 | 0.018 |

| Pain with anxiety in surgical area | - | 5 (5.8), 2.5-12.9 | |

| Concerned about scars | - | 15 (17.4), 10.9-26.8 | |

| Gallstones recurrence | 9 (10.5), 5.6-18.7 | ||

| Cholecystitis recurrence | 3 (3.5), 1.2-9.8 |

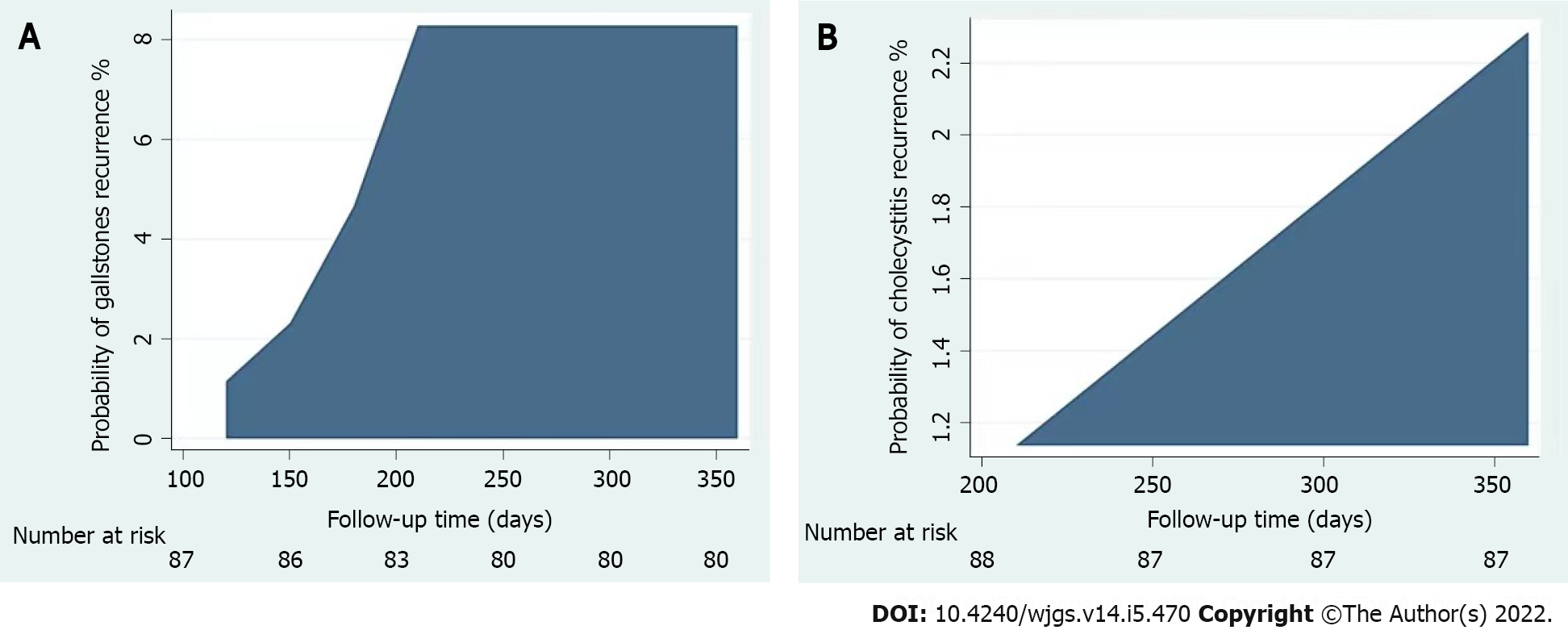

Nine NOTES patients had recurrence of gallbladder stones suggested by abdominal ultrasound. The recurrent gallbladder stones were all mud-like stones with a median recurrence time of 210 d (IQRs, 165-255). The recurrence rate was 10.5% (95%CI: 5.1%-17.2%; n = 9/85); 5 underwent cholecystectomy; 4 patients were asymptomatic and they did not wish to undergo further therapy with either NOTES or LC. We recommended re-NOTES or LC for recurrent cases. The post-operative pathology revealed chronic cholecystitis; 3.5% (95%CI: 1.1%-9%; n = 3/85) of patients had pain in the right upper abdomen and the diagnosis of cholecystitis recurrence was made by ultrasound and CT examination, of which 1 (1.1%, 95%CI: 0.2%-5.8%) patient had gallbladder stones combined with cholecystitis. In patients with recurrence who did not receive surgical treatment, symptoms were significantly reduced after antibiotic treatment. Figure 4A shows the cumulative incidence of recurrent gallbladder stones and Figure 4B shows recurrent cholecystitis in the NOTES patients. To identify risk factors for recurrence of gallbladder stones, we performed univariate Cox regression analysis of gender, baseline leukocytes, number of gallstones, and age, and none of these factors were statistically significant for recurrence of gallbladder stones.

Symptomatic gallstones are common and cholecystectomy remains the ‘gold standard’ for their management[25,26]. In 1987, the first LC was conducted which ushered in the age of cholecystectomy with minimal trauma and rapid recovery. This approach demonstrated superiority and created a precedent for minimally invasive operations. Subsequently, with improved technology, many patients with cholelithiasis worldwide have undergone LC and this technique has become the standard treatment for cholelithiasis. However, simple gallstone extraction with gallbladder preservation (cholecystolithotomy) has been proposed in order to preserve the normal physiological function of the gallbladder, avoid post-cholecystectomy syndrome, bile duct injury, complications due to abdominal wall incisions, bile reflux gastritis, and reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal cancer[27-29]. The justification for this practice includes considerations regarding safety, reduced short- and long-term complications as well as cosmetic results and patient satisfaction. Besides this, in clinical practice, we have found that many Chinese patients express a strong desire for preservation of their gallbladder. In response to the clinical desires and importance of gallbladder preservation in a large number of patients, we developed pure NOTES trans-rectal gallbladder preserving cholecystolithotomy as an ultra-minimally invasive technique for removal of gallbladder stones and gallbladder preservation.

Both LC and NOTES approaches have advantages and disadvantages. The advantages of NOTES cholecystolithotomy include: (1) Organ retention and preserved biological function; (2) No incision on the body surface; (3) Early diet intake (e.g., 6 h after the procedure patients are able to take a liquid diet); (4) Reduced post-operative pain; and (5) Fewer long-term complications compared to LC.

The problem with this approach is the current longer procedure time than that for LC and the potential for recurrence of gallstones. Long operative time is expected during the early clinical stage. During initial laparoscopic surgery, a 2-3 h operation was common. With experience and improved techniques, the operative time for NOTES cholecystolithotomy is expected to decrease.

Gallstone recurrence remains a concern. A recent report showed that the average recurrence risk for percutaneous cholecystolithotomy was 3% in 4 years and 10% in 15 years[30]. In China, a long-term analysis of the gallstone recurrence rate after laparoscopic cholecystolithotomy over more than 15 years reported a rate of 10.1% within both 10 and 15 years[31]. In our study, the recurrence risk of gallstones was 9.8% (9/94) during 6 to 40 mo of follow-up. Widespread use of NOTES cholecystolithotomy may require development of a reliable method to prevent recurrence of gallstones. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial reported that ursodeoxycholic acid is a safe and effective drug for the prevention of gallstone recurrence[32]. In an another meta-analysis Li et al[33] noted that not taking oral ursodeoxycholic acid after gallbladder preserving therapy increased the rate of stone recurrence[33]. Therefore, we recommend that patients who undergo cholecystolithotomy take ursodeoxycholic acid orally to prevent the recurrence of stones. However, further studies are needed to explore the mechanism, dosing and duration of therapy to prevent recurrence of gallstones before final recommendations are made.

The advantage of LC is a shorter procedure time than with NOTES. Disadvantages include: (1) The organ is resected so the loss of its biological function may result in long-term complications; (2) A scar on the body surface; (3) Diet intake is delayed (e.g. on day 2); (4) Risk of incision-related complications; and (5) More short- and long-term complications than that with NOTES (abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, fatty food intolerance, indigestion, association with colon cancer, functional gastrointestinal and psychological conditions)[14-18].

There was no significant difference in duration of hospital stay between the two groups. Initially, we admitted patients after undergoing NOTES procedure for a longer than usual time as this was a preliminary study with a limited sample size. Post-operative stay ranged between 3 and 5 d vs same day surgery for LC in the United States and western world, which might raise questions. The explanation for this is that in China the standard of post-operative care is different, and after all types of abdominal surgery (laparoscopic or open surgery) patients remain in hospital under observation for 3-5 d.

In our study, the most significant differences between the two groups were long-term complications and no wound infections. Although, LC seems to be a 50 min procedure with a good outcome, its long-time complications are largely unstudied including post-cholecystectomy syndrome and a possible association with colon cancer. On the other hand, the only long-term reported (10-15 years of follow-up) complication of percutaneous cholecystolithotomy has been gallstones recurrence. The main reported factors associated with the recurrence of gallstones are a family history of cholelithiasis, a preference for greasy food and gallbladder dysfunction prior to cholecystolithotomy[29-33].

Compared with LC, NOTES is more than a cosmetic technique to perform surgery as it also has the potential to reduce anesthesia requirements, accelerate patient recovery, and, above all, provide minimally invasive access to organs that are otherwise difficult to access with conventional open or laparoscopic approaches. In addition, some patients refuse surgery and some older patients are not considered candidates for surgical procedures. NOTES provides an alternative option to treat gallstone disease. Although we found short-term complications and recurrences, overall, the safety and efficacy were good with NOTES. With time and improved technology these complications will likely be reduced.

This study has some limitations, including NOTES is a new technique, a retrospective study design, small cohort, and absence of a control group which makes the study prone to attrition and possible loss of clinical data. The same limits the generalizability of the study. Additional studies especially larger multi-center trials are needed to confirm the advantages shown here, and to understand the future for this innovative new approach in the treatment of symptomatic gallstones.

In conclusion, NOTES appears to be a minimally invasive and feasible alternative technique for the management of patients with symptomatic gallstones. In our study more than 85% of patients showed good results without complications. Its advantages include no skin wound, organ retention, quick recovery, fewer post-operative complications, and patient satisfaction. Although, this procedure is unlikely to immediately replace LC, it proved useful for patients wishing to avoid surgical resection, and produced good results. Reducing the recurrence of gallstones is essential to achieve widespread clinical adoption of NOTES.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) remains the preferred option for symptomatic gallstones. However, the gallbladder functions in regulating bile flow and storing bile, and cholecystectomy may disrupt the whole biliary system and induce subsequent complications. Simple gallstone extraction with gallbladder preservation (cholecystolithotomy) has been proposed in order to preserve gallbladder function and to avoid gallbladder resection-related complications.

In response to the clinical desires and importance of gallbladder retention in a large number of patients, we developed pure natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) trans-rectal gallbladder preserving cholecystolithotomy as an ultra-minimally invasive technique for removal of gallbladder stones and gallbladder preservation.

To compare the feasibility, safety and effectiveness of pure NOTES gallbladder-preserving cholecystolithotomy vs LC for symptomatic gallstones.

We extracted patient data from the inpatient database and adopted propensity score matching (1:1) to compare trans-rectal NOTES cholecystolithotomy and LC in patients with symptomatic gallstones.

The technical success rate for the NOTES group vs the LC group was 98.9% vs 100%. Post-operative pain was similar between NOTES and LC; however, the median duration of fasting was less in NOTES patients. During the follow-up period, diarrhea was significantly less with NOTES (5.8%) compared to LC (18.6%). The recurrence rate of stones and cholecystitis within a median of 12 mo (range: 6-40 mo) following NOTES was 10.5% and 3.5%, respectively. Concerns regarding the presence of abdominal wall scars were present in patients following LC.

NOTES appears to be a minimally invasive and feasible alternative scar-free technique for the management of patients with symptomatic gallstones. Reducing the recurrence of gallstones is essential to achieve widespread clinical adoption of NOTES.

Although cholecystectomy remains the mainstay in gallstones treatment due to its unique merits, it may not be feasible in surgical patients at high-risk or with biliary deformity. In addition, since post-operative adverse events after removal of the gallbladder are inevitable in some patients, more and more endoscopists are interested in preservation of gallbladder function during the management of gallstones. Therefore, in our opinion NOTES cholecystolithotomy may be an alternative treatment for symptomatic gallstones, especially for patients wishing to avoid surgical resection.

We express our gratitude to Professor David Y Graham, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, United States, for his encouragement and assistance in revising the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cianci P, Italy; Tantau AI, Romania S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Zeng Q, He Y, Qiang DC, Wu LX. Prevalence and epidemiological pattern of gallstones in urban residents in China. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1459-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bar-Meir S. Gallstones: prevalence, diagnosis and treatment. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:111-113. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Festi D, Dormi A, Capodicasa S, Staniscia T, Attili AF, Loria P, Pazzi P, Mazzella G, Sama C, Roda E, Colecchia A. Incidence of gallstone disease in Italy: results from a multicenter, population-based Italian study (the MICOL project). World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5282-5289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Duncan CB, Riall TS. Evidence-based current surgical practice: calculous gallbladder disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:2011-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Litynski GS. Highlights in the History of Laparoscopy. Barbara Bernert Verlag. 1996;165-168. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Zanghì G, Leanza V, Vecchio R, Malaguarnera M, Romano G, Rinzivillo NM, Catania V, Basile F. Single-Incision Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: our experience and review of literature. G Chir. 2015;36:243-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Talseth A, Lydersen S, Skjedlestad F, Hveem K, Edna TH. Trends in cholecystectomy rates in a defined population during and after the period of transition from open to laparoscopic surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:92-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rao GV, Reddy DN, Banerjee R. NOTES: human experience. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008;18:361-70; x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Akiyama H, Nagusa Y, Fujita T, Shirane N, Sasao T, Iwamori S, Hidaka T, Okuhara T. A new method for nonsurgical cholecystolithotomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;161:72-74. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kerlan RK Jr, LaBerge JM, Ring EJ. Percutaneous cholecystolithotomy: preliminary experience. Radiology. 1985;157:653-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pai RD, Fong DG, Bundga ME, Odze RD, Rattner DW, Thompson CC. Transcolonic endoscopic cholecystectomy: a NOTES survival study in a porcine model (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:428-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ye L, Liu J, Tang Y, Yan J, Tao K, Wan C, Wang G. Endoscopic minimal invasive cholecystolithotomy vs laparoscopic cholecystectomy in treatment of cholecystolithiasis in China: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2015;13:227-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jaunoo SS, Mohandas S, Almond LM. Postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS). Int J Surg. 2010;8:15-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barrett M, Asbun HJ, Chien HL, Brunt LM, Telem DA. Bile duct injury and morbidity following cholecystectomy: a need for improvement. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1683-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lum YW, House MG, Hayanga AJ, Schweitzer M. Postcholecystectomy syndrome in the laparoscopic era. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16:482-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang Y, Peng J, Li X, Liao M. Endoscopic-Laparoscopic Cholecystolithotomy in Treatment of Cholecystolithiasis Compared With Traditional Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:377-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tsai MC, Chen CH, Lee HC, Lin HC, Lee CZ. Increased Risk of Depressive Disorder following Cholecystectomy for Gallstones. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Renz BW, Bösch F, Angele MK. Bile Duct Injury after Cholecystectomy: Surgical Therapy. Visc Med. 2017;33:184-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abbasoğlu O, Tekant Y, Alper A, Aydın Ü, Balık A, Bostancı B, Coker A, Doğanay M, Gündoğdu H, Hamaloğlu E, Kapan M, Karademir S, Karayalçın K, Kılıçturgay S, Şare M, Tümer AR, Yağcı G. Prevention and acute management of biliary injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Expert consensus statement. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2016;32:300-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zha Y, Chen XR, Luo D, Jin Y. The prevention of major bile duct injures in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the experience with 13,000 patients in a single center. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:378-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu B, Du B, Pan Y. Video of the Month: Transrectal Gallbladder-Preserving Cholecystolithotomy via Pure Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery: First Time in Humans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Du B, Fan YJ, Zhao LX, Geng XY, Li L, Wu XW, Zhang K, Liu BR. A reliable detachable balloon that prevents abdominal cavity contamination during transrectal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. J Dig Dis. 2019;20:383-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhao LX, Liu ZZ, Ullah S, Liu D, Yang HY, Liu BR. The detachable balloon: A novel device for safe trans-rectal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:931-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lammert F, Gurusamy K, Ko CW, Miquel JF, Méndez-Sánchez N, Portincasa P, van Erpecum KJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Wang DQ. Gallstones. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 590] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Qu Q, Chen W, Liu X, Wang W, Hong T, Liu W, He X. Role of gallbladder-preserving surgery in the treatment of gallstone diseases in young and middle-aged patients in China: results of a 10-year prospective study. Surgery. 2020;167:283-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Du S, Zhu L, Sang X, Mao Y, Lu X, Zhong S, Huang J. Gallbladder carcinoma post gallbladder-preserving cholecystolithotomy: a case report. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2012;1:61-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tan YY, Zhao G, Wang D, Wang JM, Tang JR, Ji ZL. A new strategy of minimally invasive surgery for cholecystolithiasis: calculi removal and gallbladder preservation. Dig Surg. 2013;30:466-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhu X, Liu J, Wang F, Zhao Q, Zhang X, Gu J. Influence of traditional Chinese culture on the choice of patients concerning the technique for treatment of cholelithiasis: Cultural background and historical origins of gallbladder-preserving surgery. Surgery. 2020;167:279-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gao DK, Wei SH, Li W, Ren J, Ma XM, Gu CW, Wu HR. Totally laparoscopic gallbladder-preserving surgery: A minimally invasive and favorable approach for cholelithiasis. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:395-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liu J, Li J, Zhao Q. The analyses of the results of 612 cases with gallbladder stones who underwent fibrocholedocoscope cholecystectomy for removal of caculas and preservation of gallbladder (Chinese Article). Mag Chin Surg. 2009;47:279-281. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Kosters A, Jirsa M, Groen AK. Genetic background of cholesterol gallstone disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1637:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Li W, Huang P, Lei P, Luo H, Yao Z, Xiong Z, Liu B, Hu K. Risk factors for the recurrence of stones after endoscopic minimally invasive cholecystolithotomy in China: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1802-1810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |