Published online Apr 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i4.352

Peer-review started: November 28, 2021

First decision: December 26, 2021

Revised: January 6, 2022

Accepted: March 26, 2022

Article in press: March 26, 2022

Published online: April 27, 2022

Processing time: 147 Days and 0.7 Hours

Primary encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is a rare but devastating disease that causes fibrocollagenous cocoon-like encapsulation of the bowel, resulting in bowel obstruction. The pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment strategies of EPS remain unclear so far. Since most patients are diagnosed during exploratory laparotomy, for the non-surgically diagnosed patients with primary EPS, the surgical timing is also uncertain.

A 44-year-old female patient was referred to our center on September 6, 2021, with complaints of abdominal distention and bilious vomiting for 2 d. Physical examination revealed that the vital signs were stable, and the abdomen was slightly distended. Computerized tomography scan showed a conglomerate of multiple intestinal loops encapsulated in a thick sac-like membrane, which was surrounded by abdominal ascites. The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic EPS. Recovery was observed after abdominal paracentesis, and the patient was discharged on September 13 after the resumption of a normal diet. This case raised a question: When should an exploratory laparotomy be performed on patients who are non-surgically diagnosed with EPS. As a result, we conducted a review of the literature on the clinical manifestations, intraoperative findings, surgical methods, and therapeutic effects of EPS.

Recurrent intestinal obstructions and abdominal mass combined with the imaging of encapsulated bowel are helpful in diagnosing idiopathic EPS. Small intestinal resection should be avoided.

Core Tip: Primary encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS), also called an abdominal cocoon, is so rare that the etiology, pathogenesis, treatment strategies of primary EPS remain vague. We reported a case of primary EPS and carried out a comprehensive literature analysis. The data indicated for the first time that recurrent intestinal obstructions and abdominal mass combined with the imaging of encapsulated bowel are helpful in diagnosing primary EPS. Surgical treatments are promising, but care should be taken to avoid small intestinal resection. Elective abdominal exploration might decrease complications of patients with primary EPS, but further research is required to substantiate this.

- Citation: Deng P, Xiong LX, He P, Hu JH, Zou QX, Le SL, Wen SL. Surgical timing for primary encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(4): 352-361

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i4/352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i4.352

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is a rare but chronic syndrome, clinically presenting as acute and subacute intestinal obstruction, with abdominal pain, distention, vomiting, and constipation. EPS can be classified as primary (idiopathic) and secondary (cases where causes for the disease have been identified)[1]. Secondary EPS cases are reported to be associated with peritoneal dialysis (PD), tuberculosis, β-adrenergic blocker usage, endometriosis, etc[2-5]. With the broader applications of PD, the cases of PD-related EPS have increased up to 0.7%[6]. The pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment strategies of secondary EPS have been well established[7-9]. The term primary EPS, which is also called idiopathic EPS, was first used by Foo et al[8] in 1978 to describe EPS cases of unknown origin in young women residing in tropical or subtropical countries. However, primary EPS has since been found to develop in elderly men. The etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment strategies for primary EPS remain vague. This paper reports a patient diagnosed with primary EPS and compiles 63 primary EPS cases reported in the literature.

A 44-year-old female patient was admitted to the emergency department of our institution on September 6, 2021, with complaints of abdominal distention and bilious vomiting for 2 d.

The patient had experienced abdominal distension and bilious vomiting the day before with no obvious precipitating factors. She had no fever, abdominal pain, constipation, and normal menstruation. She was treated with fasting and parenteral nutrition; the patient ceased vomiting, but abdominal distention continued.

She had three episodes of abdominal pain, abdominal distention, and bilious vomiting. The last episode occurred 3 years before, with abdominal distention and massive ascites. The patient recovered after abdominal paracentesis, which indicated bloody ascites. A year ago, she had schizophrenia and took aripiprazole orally (10 mg QD). She had untreated menstrual cramps when she was young, and her menstruation is regular. No weight loss was observed before.

There was no unremarkable personal or family history.

The patient’s vital signs were stable and the abdomen was slightly distended. There was mild tenderness in the right upper abdomen, but there was no rebound tenderness. A palpable, soft, low mobility mass (6 cm × 8 cm) was detected in the upper right abdomen, and the abdomen ascites sign was positive.

Leukocyte count: 5.66 × 109/L, percentage of neutrophils (NEU%): 65.2%; Hemoglobin: 122 g/L; C-reactive protein: 14.3 mg/L; carcinoembryonic antigen: 2.1 ng/mL; and tuberculosis antibody and T.Spot-TB tests were negative.

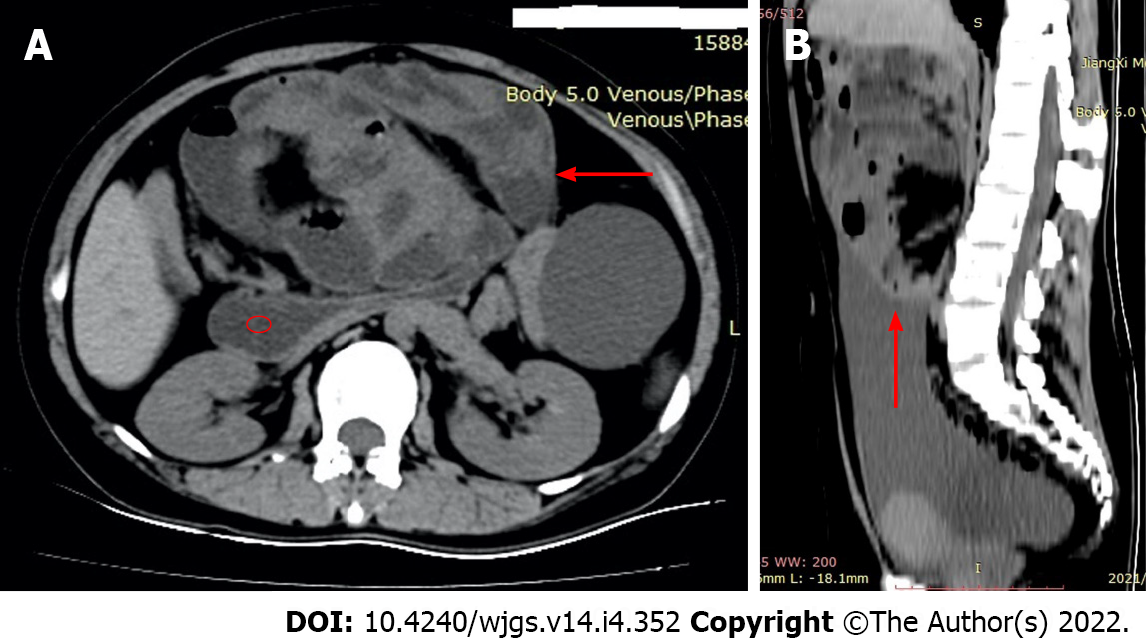

Computerized tomography (CT) scan showed a conglomerate of multiple intestinal loops encapsulated in a thick sac-like membrane, which was surrounded by abdominal ascites (Figure 1). “Gourd sign” (Figure 1A) was also observed in this case, which refers to the expansion of the horizontal part of the duodenum caused by an abdominal cocoon.

According to the clinical manifestations of recurrent intestinal obstruction, abdominal mass, and imaging features of encased bowel, this case was clinically diagnosed as primary EPS.

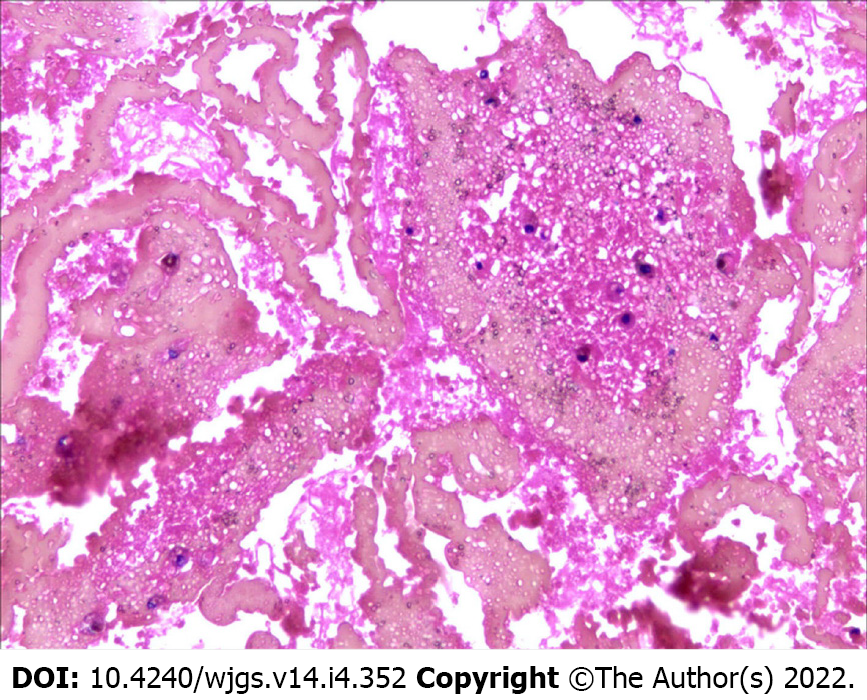

Laparoscopic exploration was proposed but was not accepted by the patient and her husband. Abdominal drainage was performed for 3 d, and a total of 2200 mL of blood liquid was removed. No carcinoma cells were found in the centrifugal cytology of ascites (Figure 2).

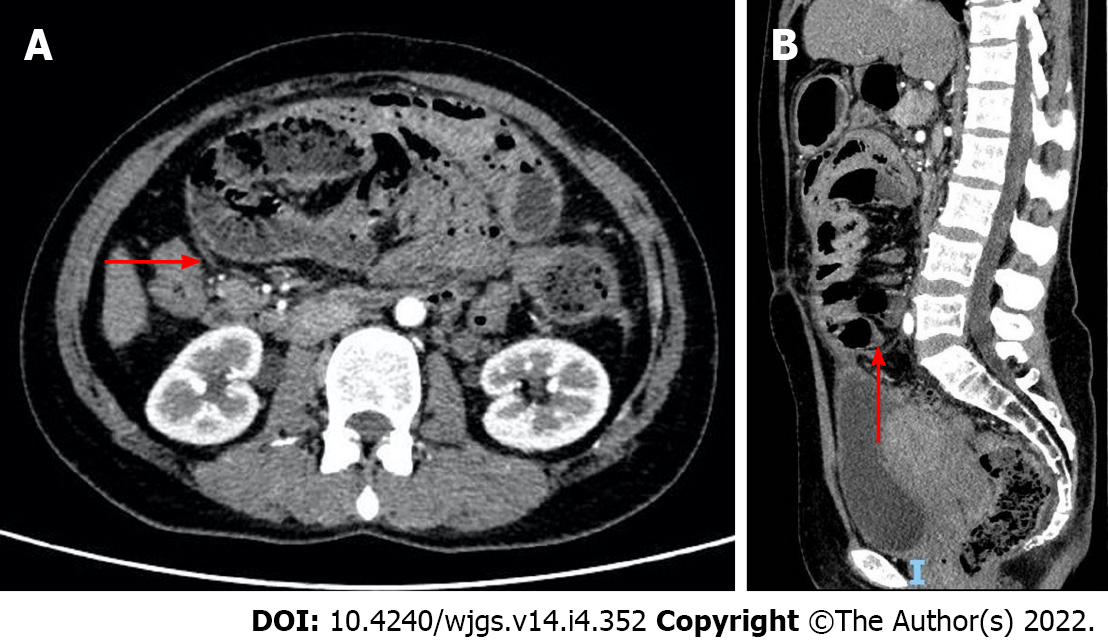

After this, the patient felt well, her abdominal distention was completely relieved, and she was put on a semi-liquid diet. After abdominal ultrasound confirmed the absence of ascites in the abdominal cavity, an abdominal contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) (September 9, 2021) scan was arranged, which revealed that the entire small intestine was dilated, clustered, and wrapped in an enhancing sac, separating the intestine from ascending colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon (Figure 3). She was discharged on September 13 after resuming a normal diet, with no recurrence of symptoms in the following month.

A systematic search of the literature, focusing on article titles and abstracts of publications in the English language using the PubMed database, was performed; the publication date of these articles was from January 2004 to September 2021. The search was executed utilizing the following keywords: “abdominal cocoon”, “encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis”, “sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis”, and “peritoneal encapsulation”. Manual searches of reference lists of the publications were performed to supplement the electronic search.

Case series without clinical details were excluded. Case reports with features of EPS that might be associated with PD, including abdominal tuberculosis, abdominal surgery, recurrent peritonitis, ventriculoperitoneal or peritoneovenous shunts, liver transplantation, abdominal trauma, beta-blocker treatment (practolol or propranolol), intraperitoneal chemotherapy, endometrioid carcinomas, intraperitoneal povidone-iodine use, liver cirrhosis, carcinomatous peritonitis, fibrogenic foreign material, systemic lupus erythematosus, and parasitic infection, were determined to be secondary EPS and were excluded.

Two investigators independently read the articles. The following information was extracted from the reports: Country (of the author), year (of publication), age/sex (of the patient), major syndrome, past history, major symptoms (of peritonitis and abdominal mass), radiologic tools, ascites characteristics, operations, intraoperative findings, histopathology, curative effect, and follow-up status. A total of 52 reports[10-61] from January 2004 to September 2021 with data of 63 patients was reviewed (Table 1). A total of 14 females with the median age of 38 years (range: 12-64 years) and 49 males with the median age of 45.5 years (range: 7-82 years) were reported; the difference of age between female and male patients was statistically significant (rank-sum test). Recurrent abdominal distention, abdominal pain or colicky pain, nausea, vomiting or bilious vomiting, anal defecation, and dehydration or malnutrition were among the symptoms reported by the patients. Also, 68.25% of the cases reported chronic symptoms, with the duration of the syndrome being more than 2 mo. Moreover, there were significant differences in the distribution of symptoms between male and female patients, with female patients exhibiting more acute symptoms. There were only 4.76% of the cases with the peritonitis symptom of rebound tenderness. Abdominal mass was palpable in 34.92% of cases, and only five patients (7.94%) were noted with ascites.

| Aspects of case description | Male, n = 49 | Female, n = 14 | Frequency as %, Z, χ2 | ||

| Age | R (7-82), M = 45.5 | R (12-64), M = 38 | Z = 4.833 | ||

| Duration of symptoms | > 2 mo | 37 | 6 | 68.25 | χ2 = 8.625, P < 0.01 |

| < 2 mo | 3 | 0 | 4.76 | ||

| ≤ 1 mo | 9 | 8 | 26.98 | ||

| Sign of peritonitis | Not mentioned | 12 | 5 | 26.98 | χ2 = 0.484, P > 0.5 |

| Soft | 12 | 4 | 25.40 | ||

| Tenderness | 23 | 4 | 42.86 | ||

| Rebound tenderness | 2 | 1 | 4.76 | ||

| Abdominal mass | 15 | 7 | 34.92 | ||

| Ascites | 2 | 3 | 7.94 | ||

| Classification | Not mentioned | 2 | 1 | 4.76 | χ2 = 9.422, P < 0.01 |

| Type I | 13 | 2 | 23.81 | ||

| Type II | 26 | 5 | 49.21 | ||

| Type III | 8 | 6 | 22.22 | ||

| Lack greater omentum | 6 | 0 | 9.52 | ||

| Operation | Non surgery | 2 | 1 | 4.76 | χ2 = 12.21, P < 0.01 |

| Laparotomy | 1 | 4 | 7.94 | ||

| Dissection + adhesionlysis | 39 | 9 | 76.19 | ||

| Partial resection | 7 | 0 | 11.11 | ||

| Histopathology (of the membrane) | 30 | 4 | 53.97 | ||

| Curative effect | Not mentioned | 4 | 1 | 7.94 | χ2 = 0.635, P > 0.5 |

| Uneventful recover | 37 | 11 | 76.19 | ||

| Prolonged recover | 6 | 2 | 12.70 | ||

| Leakage | 2 | 0 | 3.17 | ||

The intraoperative findings were analyzed and the cases were divided into the following three types according to the classification of primary EPS[8,9]: Type I: A segment of the small intestine is wrapped by a fibrous capsule; Type II: All intestines are encapsulated by fibers; and Type III: All small intestines and other organs are encapsulated by fibers. Type III and II EPS were more common in females than males, while only three male patients were noted with the absence of greater omentum. Nonoperative treatment was performed in three patients; exploratory surgery was performed in five patients; dissection of membrane and adhesiolysis was performed successfully in 76.19% of patients, and the partial resection of the small intestine was performed only in seven patients (11.11%).

The pathological description data were available for 53% of the cases. Most of the cases were pathologically reported as fibroconnective tissue proliferation with chronic inflammatory infiltration. Most of the patients (76.19%) recovered eventually, except for two patients who developed anastomotic leakage after partial resection of the intestine.

The conditions of intestinal membrane encapsulation have been described using a variety of terms. Akbulut[9] emphasized the correct usage of terms, such as peritoneal encapsulation (PE), abdominal cocoon, idiopathic EPS, and secondary EPS. PE is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by an accessory peritoneal membrane derived from the yolk sac peritoneum in the early stages of fetal life[62]; it is not the consequence of chronic inflammation. Unlike PE, EPS is an acquired disease and is associated with chronic peritoneal inflammation that might be provoked by various factors[63]. Depending on the underlying triggering factors and the properties of the fibrocollagenous membrane, EPS can be classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary[64]. The primary form (EPS of unknown origin) is also known as an abdominal cocoon and was first described by Foo et al[8] in 1978.

Primary EPS was thought to be present in tropical and subtropical areas, leading to theories of gynecologic infection or retrograde menstruation as the cause[65]. Although several studies have confirmed the equatorial predilection of primary EPS, men are more vulnerable to EPS than women[66]; however, female patients are younger than men when they develop symptoms.

The diagnosis of EPS was based on clinical manifestations and imaging findings, and most patients were diagnosed during explorative laparotomy. Recurrent intestinal obstructions characterize the clinical manifestation of primary EPS. In a large case series of primary EPS, the average duration of symptoms was 3.9 years before malnourishment symptoms developed[66]. In our study, 68.25% of the patients had a history of recurrent intestinal obstructions for more than 3 mo. While some patients with idiopathic EPS had no symptoms, the majority had abdominal pain, distention, nausea, vomiting or bilious vomiting, constipation, appetite loss, weight loss, dehydration, and malnutrition.

In this study, the physical examination of EPS patients revealed a higher occurrence of mild tenderness (42.86%) compared to rebound tenderness. The abdominal mass was palpable in 34.9% of patients, which is inconsistent with the literature report[8]. This may be due to the difference in case selection methods. Massive ascites was rare and did not seem to indicate a serious condition. There were five patients with massive ascites in the reports reviewed; one case improved by paracentesis, and four cases reported an uneventful recovery after the operation. Bloody ascites was rarer but found in both male (n = 15) and female (n = 21) patients, which questions theories of retrograde menstruation. Therefore, there may be a different cause for the massive bloody ascites in patients with primary EPS.

Blood tests did not report abnormal values, except for some patients with dehydration, electrolyte disorder, and malnutrition. The various imaging tools available for diagnosing EPS are erect abdominal X-ray, ultrasonography, barium meal, and CT or CECT. The air-fluid levels of dilated small bowel of EPS patients are visible in erect abdominal X-rays but are non-specific[28]. Ultrasound may show peritoneal thickening, ascites, and dilated bowel loops enclosed within a membrane; barium meal studies of the small intestine are useful in detecting clumped small bowel loops in the abdomen, which is also known as the cauliflower sign. CT or CECT may be the first choice for preoperative diagnosis of idiopathic EPS by providing the following image features: (1) Thickened jejunal and ileal loops encased in a thick fibrocollagenous membrane[27]; (2) “cauliflower-like” sign[67] or abdominal cystic masses with intestines freely floating in the fluid; and (3) “bottle gourd” sign[29] or dilated duodenum in patients with abdominal cocoon due to jejunal obstruction. Out of these, feature one is more common and specific.

Although the diagnosis of primary EPS is facilitated by the patient`s past history, existing symptoms, physical signs, radiological imaging, and above all, high-level clinical suspicion are major factors contributing to proper detection of the disease[47]. In this study, the preoperative diagnosis rate of primary EPS was low, and most patients were diagnosed in exploratively laparotomy or laparoscopy[11,17].

Presently, the management strategy of secondary EPS associated with PD is well established. However, very few reports suggest the surgical timing for patients who are non-surgically diagnosed with idiopathic EPS. Whether non-surgical management, such as tamoxifen, is efficacious for idiopathic EPS[15]. Célicout et al[68] believed non-surgical treatment is required in ascites and subacute intestinal obstruction.

Primary EPS could be categorized into three types according to the extent of bowel encapsulated by the membrane. Type II refers to all types of intestines encapsulated by a membrane and is the most common. In this study, the greater omentum was absent in six male patients[17,18,32,41,56,59], with age ranging from 19 years to 69 years. These cases may be diagnosed as PE or primary EPS, as both are accompanied by embryonic abnormalities[58], such as the absence of greater omentum or greater omentum dysplasia.

Dissection of membrane and adhesiolysis should be performed to all encased intestinal segments by concentrating on the following tips: (1) operate softly and lightly to avoid damaging the bowel and causing iatrogenic bowel perforation[46,54]; (2) resection of the intestine should be performed only when the bowel is nonviable; (3) anastomosis should not be the primary choice as it may increase the incidence of anastomotic leakage[25,47,68]; (4) prophylactic appendectomy is worth recommending because it is difficult to surgically treat acute appendicitis that may occur later[41]; (5) in order to reduce the complication of postoperative adhesive intestinal obstruction, it is recommended that nasointestinal obstruction tube should be installed during the operation[32]; and (6) application of an anti-adhesive substance may help prevent the patients from developing early postoperative small bowel obstruction[41,54].

Thirty-four reports describe the pathological features of the cases. The characteristic histopathological features were fibrocollagenous tissue proliferation, moderate chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and lymphatic endothelial cells[10,14,20]; some cases were accompanied by calcification[30] and hyalinization[36].

Of the 63 cases we reviewed, three patients were discharged after non-surgical treatment, five patients underwent exploratory laparotomy only, while membrane dissection and adhesiolysis were successfully performed on 76.19% of cases. Partial resection of the small bowel was performed for seven cases, two of which developed leakage, resulting in one death[47]. Early postoperative small bowel obstruction[59] was common and difficult to manage, leading to the delayed recovery of eight cases. Total parenteral nutrition with complete gastrointestinal rest was proposed[69], while reoperation was recommended. Other complications, such as poorly healed incision[21], were the cause of the prolonged recovery of one case. However, in general, the surgical effect of primary EPS seems optimistic, which is in contrast with that of secondary EPS associated PD[70].

Owing to the uncommon nature of primary EPS, its etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment strategies remain unclear. This paper presents a case of non-surgically diagnosed primary EPS, treated with paracentesis, and her CT scan with and without ascites. Recurrent intestinal obstructions and abdominal mass combined with the imaging of encapsulated bowel help diagnose primary EPS. The surgical effect of excision of membrane and adhesiolysis seems optimistic; however, small intestinal resection should be avoided as it could lead to anastomotic leakage. Elective abdominal exploration might decrease the complications of primary EPS patients with the recurrent syndrome, but further research is required to substantiate this.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bairwa DBL, India; Mohammed F, Sudan S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Dave A, McMahon J, Zahid A. Congenital peritoneal encapsulation: A review and novel classification system. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:2294-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Ulmer C, Braun N, Rieber F, Latus J, Hirschburger S, Emmel J, Alscher MD, Steurer W, Thon KP. Efficacy and morbidity of surgical therapy in late-stage encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Surgery. 2013;153:219-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singal R, Satyashree B, Mittal A, Sharma BP, Singal S, Zaman M, Shardha P. Tubercular abdominal cocoon in children - a single centre study in remote area of northern India. Clujul Med. 2017;90:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Noh SH, Ye BD, So H, Kim YS, Suh DJ, Yoon SN. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in a long-term propranolol user. Intest Res. 2016;14:375-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Katz CB, Diggory RT, Samee A. Abdominal cocoon. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rigby RJ, Hawley CM. Sclerosing peritonitis: the experience in Australia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, Nakayama M, Miyazaki M, Nakamoto H, Tranaeus A. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25 Suppl 4:S83-S95. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, Foong WC, Sinniah R. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg. 1978;65:427-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akbulut S. Accurate definition and management of idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:675-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Bhatta OP, Verma R, Shrestha G, Sharma D, Dahal R, Kansakar PBS. An unusual case of intestinal obstruction due to abdominal cocoon: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;85:106282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aziz W, Malik Y, Haseeb S, Mirza RT, Aamer S. Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome: A Laparoscopic Approach. Cureus. 2021;13:e16787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yin MY, Qian LJ, Xi LT, Yu YX, Shi YQ, Liu L, Xu CF. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in an AMA-M2 positive patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:6138-6144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ulusoy C, Nikolovski A, Öztürk NN. Difficult to Diagnose the Cause of Intestinal Obstruction due to Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saqib SU, Farooq R, Saleem O, Moeen S, Chawla TU. Acute presentation of cocoon abdomen as septic peritonitis mimicking with strangulated internal herniation: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2021;7:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wetherell J, Woolley K, Chadha R, Kostka J, Adilovic E, Nepal P. Idiopathic Sclerosing Encapsulating Peritonitis in a Patient with Atypical Symptoms and Imaging Findings. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2021;2021:6695806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Karona P, Blevrakis E, Kastanaki P, Tzouganakis A, Kastanakis M. Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome: An Extremely Rare Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction. Cureus. 2021;13:e14351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tang H, Xia R, Xu S, Tao C, Wang C. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis presenting with paroxysmal abdominal pain and strangulated mechanical bowel obstruction: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Song WJ, Liu XY, Saad GAA, Khan A, Yang KY, Zhang Y, Liu JY, He LY. Primary abdominal cocoon with cryptorchidism: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lasheen O, ElKorety M. Abdominal Cocoon or Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis: A Rare Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sivakumar J, Brown G, Galea L, Choi J. An intraoperative diagnosis of sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang Z, Zhang M, Li L. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: three case reports and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520949104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kang JH. A rare case of intestinal obstruction: Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis of unknown cause. Turk J Emerg Med. 2020;20:152-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou H, Xu J, Xie X, Han J. Idiopathic cocoon abdomen with congenital colon malrotation: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2020;20:124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Akbas A, Hacım NA, Dagmura H, Meric S, Altınel Y, Solmaz A. Two Different Clinical Approaches with Mortality Assessment of Four Cases: Complete and Incomplete Type of Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome. Case Rep Surg. 2020;2020:4631710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Park GH, Lee BC, Hyun DW, Choi JB, Park YM, Jung HJ, Jo HJ. Mechanical intestinal obstruction following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in a patient with abdominal cocoon syndrome. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjz370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yue B, Cui Z, Kang W, Wang H, Xiang Y, Huang Z, Jin X. Abdominal cocoon with bilateral cryptorchidism and seminoma in the right testis: a case report and review of literature. BMC Surg. 2019;19:167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Saqib SU, Pal I. Sclerosing peritonitis presenting as complete mechanical bowel obstruction: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13:310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mohakud S, Juneja A, Lal H. Abdominal cocoon: preoperative diagnosis on CT. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sharma V, Mandavdhare HS, Singh H, Gorsi U. Significance of Bottle Gourd sign on computed tomography in patients with abdominal cocoon: a case series. Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92:192-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Renko AE, Witte SR, Cooper AB. Abdominal cocoon syndrome: an obstructive adhesiolytic metamorphosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sovatzidis A, Nikolaidou E, Katsourakis A, Chatzis I, Noussios G. Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome: Two Cases of an Anatomical Abnormality. Case Rep Surg. 2019;2019:3276919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Xia J, Xie W, Chen L, Liu D. Abdominal cocoon with early postoperative small bowel obstruction: A case report and review of literature in China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Al-Azzawi M, Al-Alawi R. Idiopathic abdominal cocoon: a rare presentation of small bowel obstruction in a virgin abdomen. How much do we know? BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kirshtein B, Mizrahi S, Sinelnikov I, Lantsberg L. Abdominal cocoon as a rare cause of small bowel obstruction in an elderly man: report of a case and review of the literature. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:73-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Shah MY, Gedam BS, Sonarkar R, Gopinath KS. Abdominal cocoon: an unusual cause of subacute intestinal obstruction. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:391-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Obaid O, Alhalabi D, Ghonami M. Intestinal Obstruction in a Patient with Sclerosing Encapsulating Peritonitis. Case Rep Surg. 2017;2017:8316147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Cheng Y, Qu L, Li J, Wang B, Geng J, Xing D. Abdominal cocoon accompanied by multiple peritoneal loose body. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lim MC, Chotai NC, Giron DM. Idiopathic Sclerosing Encapsulating Peritonitis: A Rare Cause of Subacute Intestinal Obstruction. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:8206894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fei X, Yang HR, Yu PF, Sheng HB, Gu GL. Idiopathic abdominal cocoon syndrome with unilateral abdominal cryptorchidism and greater omentum hypoplasia in a young case of small bowel obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4958-4962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yang CS, Kim D. Unusual intestinal obstruction due to idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a report of two cases and a review. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016;90:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhang Y, Liu WD, He JT, Liu Q, Zhai DG. A rare case of abdominal cocoon presenting as umbilical hernia. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:1415-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Uzunoglu Y, Altintoprak F, Yalkin O, Gunduz Y, Cakmak G, Ozkan OV, Celebi F. Rare etiology of mechanical intestinal obstruction: Abdominal cocoon syndrome. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:728-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Frost JH, Price EE. Abdominal cocoon: idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Solmaz A, Tokoçin M, Arıcı S, Yiğitbaş H, Yavuz E, Gülçiçek OB, Erçetin C, Çelebi F. Abdominal cocoon syndrome is a rare cause of mechanical intestinal obstructions: a report of two cases. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Rasihashemi SZ, Ramouz A, Ebrahimi F. An unusual small bowel obstruction (abdominal cocoon): a case report. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2014;27:82-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Naniwadekar RG, Kulkarni SR, Bane P, Agrarwal S, Garje A. Abdominal cocoon: an unusual presentation of small bowel obstruction. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:173-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kadow JS, Fingerhut CJ, Fernandes Vde B, Coradazzi KR, Silva LM, Penachim TJ. Encapsulating peritonitis: computed tomography and surgical correlation. Radiol Bras. 2014;47:262-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cağlar M, Cetinkaya N, Ozgü E, Güngör T. Persistent ascites due to sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis mimicking ovarian carcinoma: A case report. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2014;15:201-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Al Ani AH, Al Zayani N, Najmeddine M, Jacob S, Nair S. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (abdominal cocoon) in adult male. A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:735-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Al-Thani H, El Mabrok J, Al Shaibani N, El-Menyar A. Abdominal cocoon and adhesiolysis: a case report and a literature review. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:381950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Awe JA. Abdominal cocoon syndrome (idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis): how easy is its diagnosis preoperatively? Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:604061. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Sharma D, Nair RP, Dani T, Shetty P. Abdominal cocoon-A rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:955-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Kayastha K, Mirza B. Abdominal cocoon simulating acute appendicitis. APSP J Case Rep. 2012;3:8. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Meshikhes AW, Bojal S. A rare cause of small bowel obstruction: Abdominal cocoon. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:272-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Bassiouny IE, Abbas TO. Small bowel cocoon: a distinct disease with a new developmental etiology. Case Rep Surg. 2011;2011:940515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Gupta RK, Chandra AS, Bajracharya A, Sah PL. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in an adult male with intermittent subacute bowel obstruction, preoperative multidetector-row CT (MDCT) diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Jayant M, Kaushik R. Cocoon within an abdominal cocoon. J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2011:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Xu P, Chen LH, Li YM. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon): a report of 5 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3649-3651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zheng YB, Zhang PF, Ma S, Tong SL. Abdominal cocoon complicated with early postoperative small bowel obstruction. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:294-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Mohd Noor NH, Zaki NM, Kaur G, Naik VR, Zakaria AZ. Abdominal cocoon in association with adenomyosis and leiomyomata of the uterus and endometriotic cyst : unusual presentation. Malays J Med Sci. 2004;11:81-85. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Devay AO, Gomceli I, Korukluoglu B, Kusdemir A. An unusual and difficult diagnosis of intestinal obstruction: The abdominal cocoon. Case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Serter A, Kocakoç E, Çipe G. Supposed to be rare cause of intestinal obstruction; abdominal cocoon: report of two cases. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:586-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Browne LP, Patel J, Guillerman RP, Hanson IC, Cass DL. Abdominal cocoon: a unique presentation in an immunodeficient infant. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:263-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Tannoury JN, Abboud BN. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: abdominal cocoon. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1999-2004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 65. | Danford CJ, Lin SC, Smith MP, Wolf JL. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3101-3111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 66. | Li N, Zhu W, Li Y, Gong J, Gu L, Li M, Cao L, Li J. Surgical treatment and perioperative management of idiopathic abdominal cocoon: single-center review of 65 cases. World J Surg. 2014;38:1860-1867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ibrarullah M, Mishra T. Abdominal Cocoon: "Cauliflower Sign" on CT Scan. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:243-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Célicout B, Levard H, Hay J, Msika S, Fingerhut A, Pelissier E. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: early and late results of surgical management in 32 cases. French Associations for Surgical Research. Dig Surg. 1998;15:697-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Cheng SP, Liu CL. Early postoperative small bowel obstruction (Br J Surg 2004; 91: 683-691). Br J Surg. 2004;91:1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Kawanishi H. Surgical and medical treatments of encapsulation peritoneal sclerosis. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;177:38-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |