Published online Feb 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i2.200

Peer-review started: August 18, 2021

First decision: October 2, 2021

Revised: October 15, 2021

Accepted: January 20, 2022

Article in press: January 20, 2022

Published online: February 27, 2022

Processing time: 188 Days and 2.4 Hours

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare nonhereditary disease with a syndrome of multiple gastrointestinal polyps, skin pigmentation, hair loss, and fingernail/toenail dystrophy. Intussusception is a serious condition with an occurrence rate of 5% in adults, which is mainly caused by intestinal tumors or other intestinal occupations.

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to abdominal distension and pain for the past year. Her nausea and vomiting symptoms had been aggravated for the past month. Previous transoral enteroscopy results one year prior showed chronic erosive gastritis protuberans, duodenitis, and jejunitis. She had sparse body hair and brown pigmentation on the skin of her hands and bilateral anterior tibias. The nails of both hands were pale and lacked luster, and the fingernail of her ring finger was longitudinally cracked. Gastroscopy showed extensive diffuse polypoid lump changes in the gastric body and antrum, of 0.5-3 cm in size. Colonoscopy showed multiple polypoid mucosal bulges in the terminal ileum and multiple polyps (0.3-5 cm) throughout the colon. The patient was diagnosed with CCS and underwent partial excision of the polyps, but she refused hormone therapy. One month later, the patient complained of nausea and vomiting, accompanied by abdominal pain and inability to pass gas or stool. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen showed gastrointestinal polyposis and ileocecal intussusception. She underwent stomach and bowel surgery.

CCS, as a rare disease with poor prognosis, should be treated aggressively. Systematic steroids, immunosuppressive agents, and biological agents were not applied; thus, the patient’s symptoms quickly progressed, and intussusception occurred. She had to undergo surgery. Improved compliance may lead to a better prognosis.

Core Tip: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS), a syndrome of multiple gastrointestinal polyps, skin pigmentation, hair loss, and fingernail/toenail dystrophy, is a rare nonhereditary disease. We report a case of CCS that quickly progressed, and intussusception occurred, which eventually led to surgery because systematic steroids, immunosuppressive agents, and biological agents were not applied. As a rare disease with poor prognosis, CCS should be treated aggressively. Meanwhile, improved compliance may lead to a better prognosis.

- Citation: Dong J, Ma TS, Tu JF, Chen YW. Surgery for Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated with intussusception: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(2): 200-210

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i2/200.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i2.200

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare nonhereditary disease with multiple gastrointestinal polyps, skin pigmentation, hair loss, and fingernail/toenail dystrophy. The disease was first reported in 1955[1]. More than 500 confirmed cases have been reported worldwide to date, resulting in an incidence of approximately 1 per million[2,3]. Approximately 75% of the existing reports are from Japan, where the incidence is approximately 3.7 per million[4].

Intussusception is a common complication in children, while in adults, the incidence of intussusception is only approximately 5% and is mainly caused by occupations, such as tumors[5].

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to abdominal distension and pain for 1 year, which had been aggravated with nausea and vomiting for 1 mo.

The patient experienced abdominal distension and pain accompanied by the absence of exhaust defecation without obvious inducement 1 year prior. She was evaluated in a local hospital before admission to our hospital. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) (July 14, 2019) showed edema and thickening of the duodenal wall, with mild dilation of some parts of the small intestine with effusion. Transoral enteroscopy showed chronic erosive gastritis protuberans, duodenitis, and jejunitis. She was treated by fasting, gastrointestinal decompression, antibiotics, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and fluid supplementation, and then she was discharged after relief of abdominal distension and pain and restoration of anal gas evacuation. The patient had cracked fingernails, accompanied by hair loss, weakened sense of taste, and repeated abdominal distension and abdominal pain starting 10 mo prior. One month prior, the patient had nausea and vomiting with aggravated abdominal distension, and diarrhea consisting of yellow-green loose stools. She experienced anorexia and fatigue. In the previous month, her weight loss was approximately 5-6 kg.

The patient was healthy overall except for a 5-year history of hypertension. She had brown pigmentation on the anterior tibia skin of her lower limbs for more than 10 years, and the pigmentation size varied from a coin-sized area when the condition was relieved to an area extending from above the ankle to below the knee when the condition was more severe. The lesion produced itching and discomfort but did not exhibit redness, swelling, or ulceration. The patient had sparse body hair since childhood and had no history of oral steroids or long-term medication use.

She had no infectious disease, drug or food allergy, surgery, or blood transfusion. She also had no family history of gastrointestinal polyposis or other genetic diseases.

Height: 157 cm; weight: 36 kg; body mass index: 14.6 kg/m2; ear temperature: 36.2 °C; breaths: 18/min; pulse: 118 beats/min; blood pressure: 110/78 mmHg. The patient was conscious and alert but less vigorous than usual. Her conjunctivas appeared pale. Brown pigments were visible, particularly on the skin of her hands and bilateral anterior tibia. She had sparse body hair. The nails of both hands were pale and lacked luster, and the fingernail of her ring finger was longitudinally cracked (Figure 1). Small nodules (the size of a red bean) in the right supraclavicular lymph node could be palpated, with clear borders and no adhesions. No edema was noted in either lower limb.

The blood test results were as follows: White blood cell count (11.63 × 109/L↑), neutrophil count (8.4 × 109/L↑), hemoglobin 119 g/L (115-150), and platelet count (545 × 109/L↑). The C-reactive protein level was 1.9 mg/L. The biochemical test results were: Albumin 23.2 g/L (40-55) and blood calcium 1.85 mmol/L (2.11-2.52). The tumor marker test results were as follows: CA19-9 41.1 U/mL (0-37), immunoglobulin E (IgE) 193/mL (0-87), and gastrin 129 ng/L (13-115). Serum Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibodies were positive. The occult blood test in stool was positive (++), and the fat globule test was positive.

No abnormalities were found in the following test results: Liver and kidney function, coagulation function, troponin level, thyroid function, routine urine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, immunoglobulin (G, A, M) levels, immunoglobulin G (IgG) 4 level, complement levels, rheumatoid factor level, hepatitis (A, B, C, D, E) antibodies, TORCH (Toxoplasma gondii, Rubella virus, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2) antibodies, Epstein-Barr virus antibodies, anemia test (ferritin, folic acid, vitamin B12), Mycobacterium tuberculosis antibodies, tuberculosis infection T cells, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, and blood lead level.

During the entire treatment, we recommended that the patient undergo further genetic examination, but she refused because of the expense.

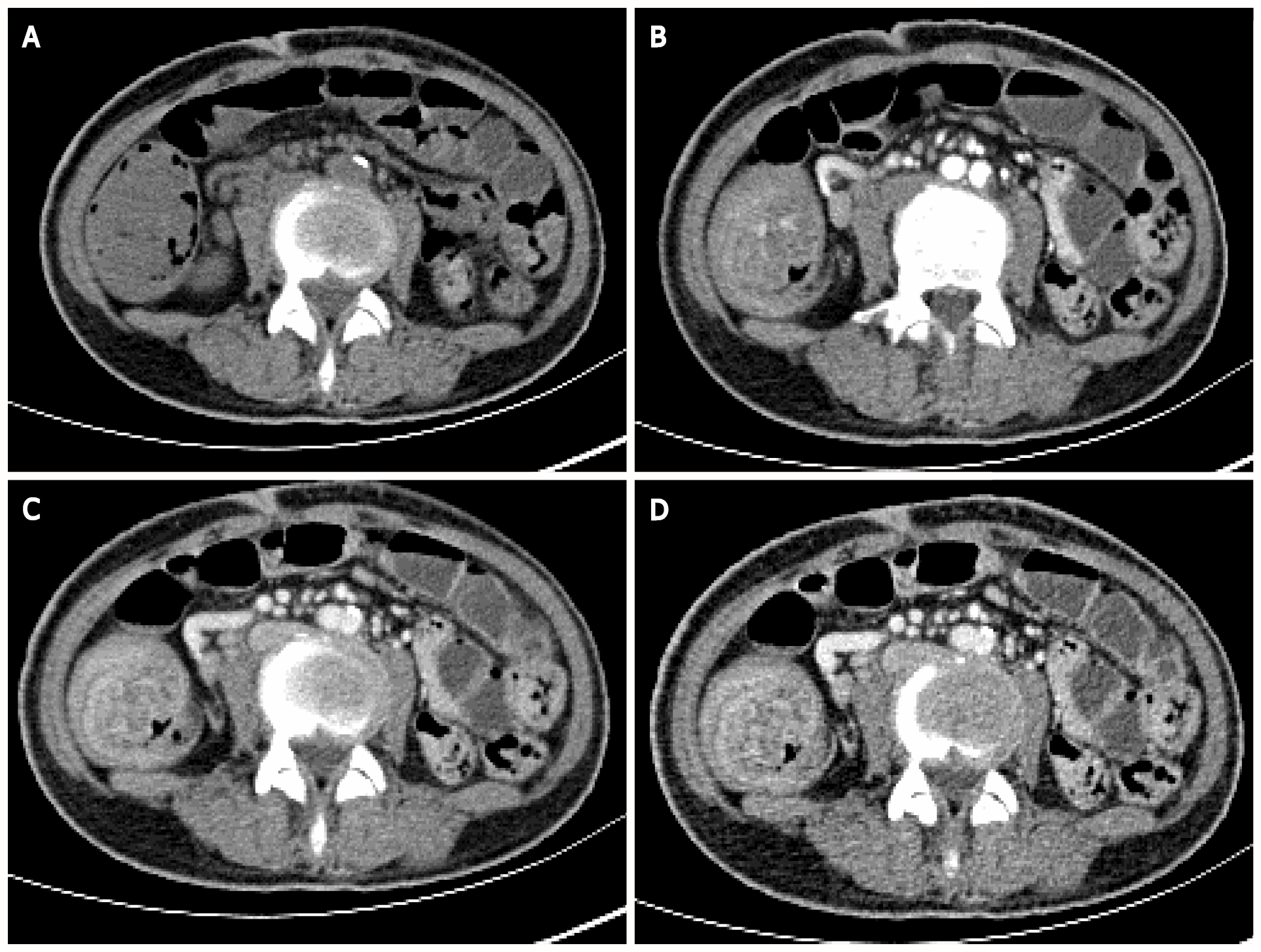

Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen suggested that the gastric wall and part of the small intestine and colon were thickened with multiple cauliflower-like and nodular protrusions and showed obvious heterogeneous enhancement. A diagnosis of multiple polyps (malignant changes were not ruled out) was considered (Figure 2).

Positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT showed multiple nodules with increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) intake in the gastric wall (SUVmax 3.4), descending duodenum and bulb, small intestine, and colon (SUVmax 7.3). Multiple areas of nodular thickening with increased FDG intake were noted in the proximal rectum. Based on her medical history, a diagnosis of multiple polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract (the possibility of malignant changes in individual polyps could not be excluded) was considered (Figure 3).

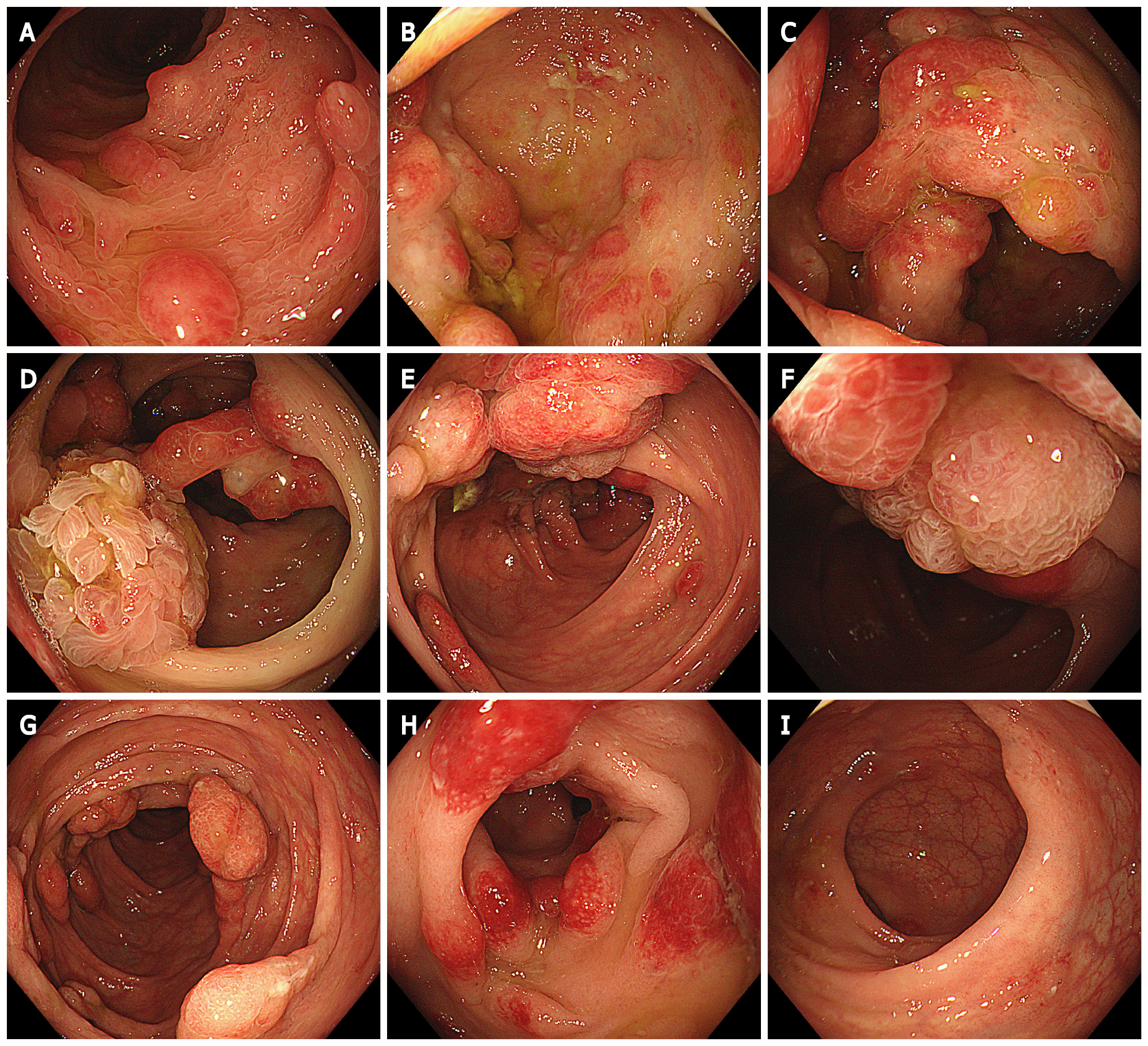

Gastroscopy showed extensive diffuse polypoid lumps of 0.5-3.0 cm in the gastric body, gastric fundus and antrum (Figure 4).

Colonoscopy showed multiple polypoid mucosal bulges in the terminal ileum and multiple polyps (0.3-5 cm) throughout the colon. Some were villus-like changes. Severe hyperemia was found on the surface. Larger polyps appeared in the ascending colon and the hepatic flexure (Figure 5).

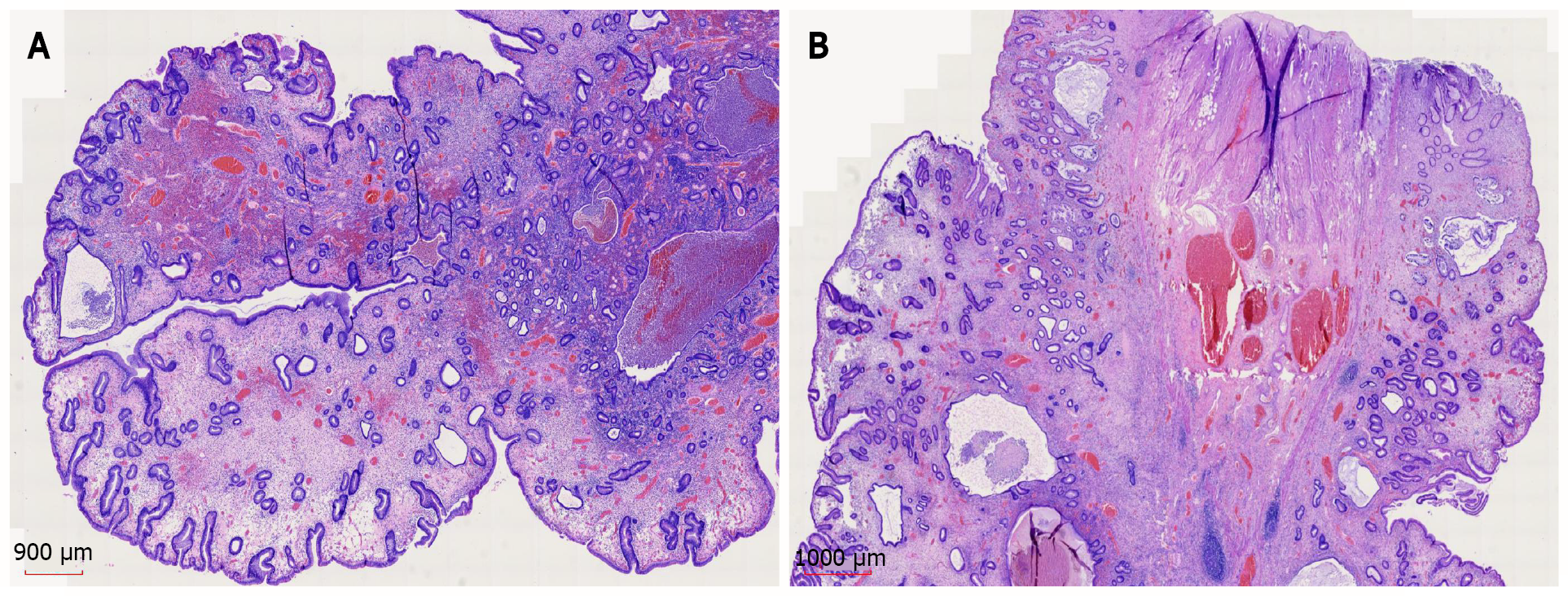

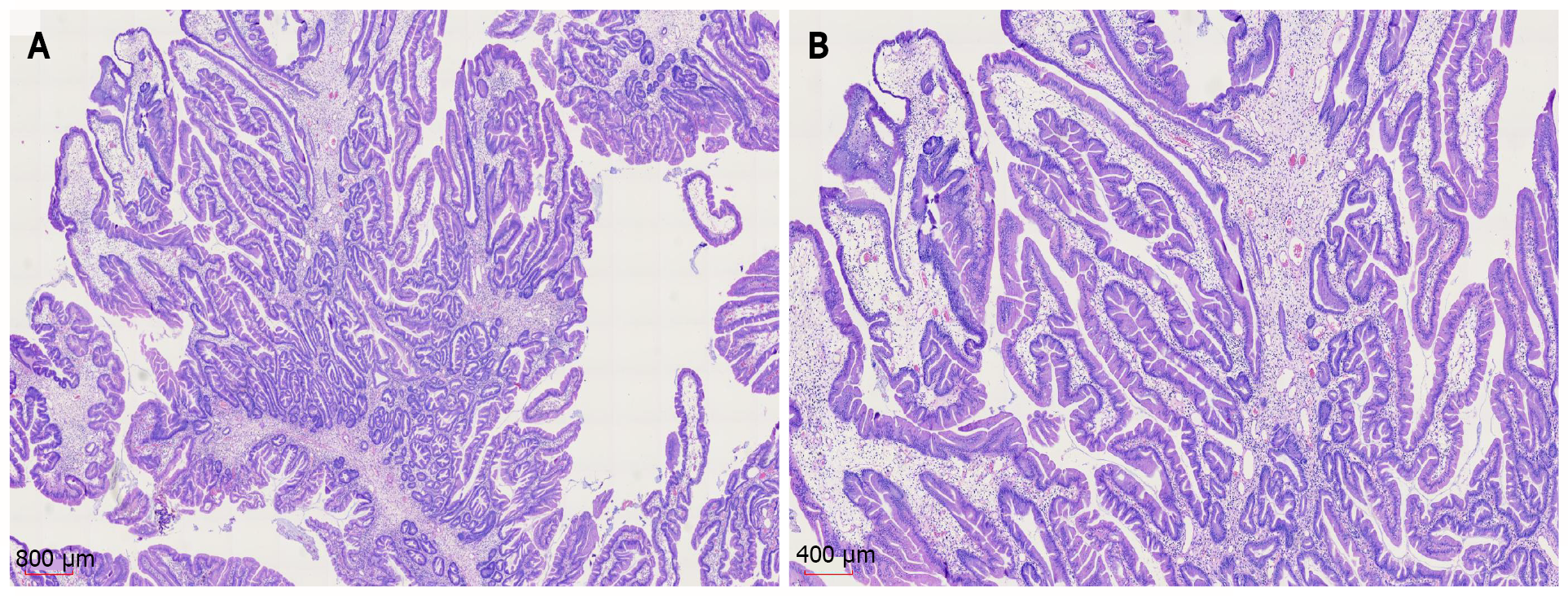

Gastroscopic pathology showed juvenile polyps in the gastric antrum (H. pylori+) (Figure 6). Colonoscopic pathology showed juvenile polyps in the ascending colon (Figure 7).

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

The patient was admitted to the hospital and treated with nutritional agents, digestive enzymes, a PPI, and anti-H. pylori agents (rabeprazole 10 mg bid + bismuth potassium citrate 0.6 g bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid + clarithromycin 0.5 g bid, 14 d). The nail dystrophy and skin pigmentation improved after treatment.

One month after treatment, the patient complained of nausea and vomiting, accompanied by abdominal pain and inability to pass gas or stool. Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen showed gastrointestinal polyposis and ileocecal intussusception (Figure 8).

After fasting, gastrointestinal decompression, somatostatin administration, PPI treatment, and total parenteral nutrition, her symptoms were not significantly improved. The patient and family members refused surgical treatment followed by glucocorticoids. Her symptoms worsened 1 mo later, and she underwent right hemicolon + partial transverse colon + partial ilium resection at another hospital. Postoperative pathology showed inflammatory changes.

After the operation, vomiting and decreased bowel movements recurred. CT showed intestinal obstruction. She underwent subtotal gastrectomy 3 mo after the surgery.

Diarrhea and the triad of abnormal ectodermal lesions (hair loss, skin pigmentation, fingernail/toenail atrophy and loss) are the most common clinical manifestations of CCS. Other manifestations include weight loss, hypoalbuminemia, edema of both lower limbs, dysgeusia, abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and itching[3]. Some patients also have electrolyte disturbances (most common types: Hypokalemia and hypocalcemia), and fractures have been reported occasionally. Almost all of the clinical features of CCS were present in this patient.

CCS is a rare hereditary or familial disorder with multiple intestinal polyps distributed throughout the digestive tract. Most are in the stomach and colon (90%), followed by 80% in the small intestine and 67% in the rectum. They are rare in the esophagus[6]. Approximately 12.3% (26/211) of CCS patients have esophageal involvement[7]. Endoscopy has demonstrated that most polyps are sessile or broad-based and diffusely distributed, vary in size, and are granular, nodular, or irregular in shape. The polyp mucosa is congested with obvious edema, and intestinal folds are thickened[2,8].

Hyperplastic polyps and hamartoma-like polyps are common in CCS histopathology examinations. In addition, 31%-71% of patients may have digestive tract adenomas or adenomatous changes during the course of this disease[9]. The pathological features of typical CCS polyps include propria edema, mild to moderate inflammatory cell infiltration, eosinophil and lymphocyte infiltration (even IgG4 plasma cell infiltration), tortuous hyperplasia of glands, and some cystic expansion filled with protein-rich liquid or concentrated mucus[2].

The histopathology of non-polyp tissue includes edema, mucus-like expansion of the propria, damage to the crypt structure (dilation or branching)[10], and mixed inflammatory infiltration composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils[11].

Due to the extremely low incidence of CCS and the small number of studies available, controversies remain regarding the causes, mechanisms, and effective treatments of CCS.

The mainstream view is that the pathogenesis of CCS is related to autoimmune disorders[12,13]. Patients may have abnormal expression of antinuclear antibodies[14], abnormal IgG4 expression[6,12] (elevated serum IgG4 or infiltration of IgG4 plasma cells in the tissue), other autoimmune diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma)[8,13], and impaired T cell regulatory function[11]. Case studies have shown that steroids and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibody therapy are not effective against CCS in some cases, suggesting that the relationship between CCS and immunity is complicated[15]. The histopathology of the nail matrix of some patients with CCS shows stromal granuloma. Because stromal hypergranulation is common in a variety of inflammatory nail diseases, the inflammatory process may be an important pathogenic factors of CCS[16]. H. pylori infection is also believed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of CCS. Watanabe et al[7] found that approximately 54% of CCS patients had H. pylori infection, and the symptoms of CCS disappeared after anti-H. pylori treatment[17,18].

The diagnosis of CCS should be based on comprehensive consideration of the medical history, physical examination, endoscopic examination and histopathological results. CCS needs to be differentiated from juvenile polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cowden syndrome, Turcot syndrome, and familial adenomatous polyposis[7,19].

The common complications of CCS include gastrointestinal bleeding with anemia, intussusception, gastrointestinal tumors, hypoproteinemia, rectal prolapse, malabsorption, electrolyte imbalance, and vitamin deficiency[20]. Rare complications include recurrent severe acute pancreatitis[21], portal vein thrombosis, membranous glomerulonephritis[14], and recurrent arteriovenous embolism[22]. The probability of a CCS patient with a malignant tumor is 13%[23]. Three histological structures, including polyps[24], adenomas, and adenocarcinomas, may be present concurrently in the gastrointestinal tract in CCS patients. Histological evidence has shown transformation of CCS from polyps to adenomas and then to adenocarcinomas. In 15%-25% of CCS patients, gastric or intestinal carcinoma is diagnosed at the onset of CCS. The total adenoma detection rate over the course of CCS is 31%-71%[7,9]. Therefore, long-term endoscopic monitoring of patients with confirmed or suspected CCS is needed[7].

Due to the low incidence of CCS and the small number of reported cases, no unified or standardized CCS treatment guidelines have been issued in China or abroad. To date, empirical treatment is mainly applied, including steroids, immunosuppressants, biological agents, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, acid blockers, nutritional support, and endoscopic surgical treatment. Steroids are currently well accepted for the treatment of CCS[12,25]. No consensus has been reached about the steroid dosage or duration. Watanabe et al[7] reported that the most significant effective dose of prednisolone for active CCS was 30-49 mg per day. Early tapering of steroids may be related to early recurrence, which suggests that the prednisolone dose should be slowly reduced after endoscopic confirmation of polyp regression. Approximately 61.1%[7] to 61.3%[3] of patients achieve clinical relief after steroid treatment. Osteoporosis is a major side effect of steroids. After steroid-induced remission, immunosuppressive maintenance therapy should be continued[26]. If the abovementioned drug treatments are ineffective, biological agents can be an option[27]. However, it has been suggested that steroids and anti-TNF-α antibodies are not effective for some CCS patients. Whether steroids or biological agents have better efficacy in IgG4-positive patients remains to be proven[15]. Early proactive drug treatment may reduce the incidences of intussusception and surgical intervention. Because most adult intussusceptions are accompanied by tumor changes, surgical treatment is the first choice once intussusception is confirmed. Endoscopic reduction is also an option, but with a high risk; in theory, reduction may lead to abdominal perforation and tumor spread[5,28]. Partial endoscopic mucosal resection plus corticosteroids and anti-plasmin treatment can be used to avoid surgery.

The prognosis of CCS is poor. Lesion size, age, and complications are factors for a poor prognosis[3]. Serious complications can be life-threatening. The 5-year survival rate is less than 45%[29]. The main causes of death are gastrointestinal bleeding, infection, malnutrition, electrolyte imbalance, and heart failure[8]. Because CCS is a rare disease, clinicians may misdiagnose it because they are not familiar with it. Meanwhile, CCS has a risk of malignancy[30]. More than 10% of CCS patients relapse after the disease is relieved via standardized steroid and endoscopic treatments. Therefore, standardized follow-up and endoscopic monitoring are essential during the whole treatment process to reduce the mortality rate of CCS. Evaluation should be performed at an interval of 6-12 mo after treatment or confirmed diagnosis[7]. During the first year after onset of the illness, the patient and her family members refused glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, or biological agents for treatment. The disease progressed rapidly even after she received symptomatic treatment, nutritional support, and surgical treatment. An in-depth understanding of CCS and advanced diagnosis and treatment may improve its prognosis; therefore, the prognosis needs to be reassessed after treatment.

In this case, endoscopy did not show large or multiple polyps at the onset of the symptoms one year prior, and no specific treatment was applied during that year. Large polyps appeared quickly in the gastrointestinal tract. After routine nutritional support and anti-H. pylori treatment, the polyps did not significantly subside. Because systematic steroids, immunosuppressive agents, and biological agents were not applied, the patient’s symptoms quickly progressed, and intussusception occurred. She had to eventually undergo surgery. Thus, CCS, a rare disease with poor prognosis, should be treated aggressively. Learning more about the disease and improved compliance may lead to a better prognosis.

We would like to show our deepest gratitude to our friend, Dr. Yi Chen, a respectable, responsible and resourceful scholar, who has provided us with valuable guidance in every stage of the writing of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Elghali MA S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Cronkhite LW Jr, Canada WJ. Generalized gastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation, alopecia and onychotrophia. N Engl J Med. 1955;252:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hoekstra E, van der Laan J, van der Voorn M. Seventy-five-year-old man with unexplained weight loss and alopecia. Gut. 2020;69:822-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu S, You Y, Ruan G, Zhou L, Chen D, Wu D, Yan X, Zhang S, Zhou W, Li J, Qian J. The Long-Term Clinical and Endoscopic Outcomes of Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11:e00167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oba MS, Murakami Y, Nishiwaki Y, Asakura K, Ohfuji S, Fukushima W, Nakamura Y, Suzuki Y. Estimated Prevalence of Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome, Chronic Enteropathy Associated With SLCO2A1 Gene, and Intestinal Behçet's Disease in Japan in 2017: A Nationwide Survey. J Epidemiol. 2021;31:139-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brill A, Lopez RA. Intussusception In Adults. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2020, StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2020. |

| 6. | Riegert-Johnson DL, Osborn N, Smyrk T, Boardman LA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome hamartomatous polyps are infiltrated with IgG4 plasma cells. Digestion. 2007;75:96-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K, Hokari R, Tanaka M, Hirata I, Hibi T, Kaunitz JD, Miura S. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:327-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Slavik T, Montgomery EA. Cronkhite–Canada syndrome six decades on: the many faces of an enigmatic disease. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:891-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sweetser S, Boardman LA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: an acquired condition of gastrointestinal polyposis and dermatologic abnormalities. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:201-203. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Raimondo M. Novel endosonographic findings in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Endoscopy. 2003;35:464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bettington M, Brown IS, Kumarasinghe MP, de Boer B, Bettington A, Rosty C. The challenging diagnosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a series of 7 cases with clinical follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:215-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK, Sanderson SO, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, Boardman LA. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: support for autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:496-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kao KT, Patel JK, Pampati V. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J Dig Dis. 2009;14:619378. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Takeuchi Y, Yoshikawa M, Tsukamoto N, Shiroi A, Hoshida Y, Enomoto Y, Kimura T, Yamamoto K, Shiiki H, Kikuchi E, Fukui H. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with colon cancer, portal thrombosis, high titer of antinuclear antibodies, and membranous glomerulonephritis. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:791-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Douglas CP, Yang PF, Riordan SM, Wong SW. Ileal intussusception and perforation associated with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:1194-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chuamanochan M, Tovanabutra N, Mahanupab P, Kongkarnka S, Chiewchanvit S. Nail Matrix Pathology in Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: The First Case Report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:860-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Okamoto K, Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Nishiyama H, Ito M, Kohno S. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: remission after treatment with anti-Helicobacter pylori regimen. Digestion. 2008;78:82-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kato K, Ishii Y, Mazaki T, Uehara T, Nakamura H, Kikuchi H, Yamagami H, Sato H, Mizuno S, Soma M, Henmi A, Masuda H, Moriyama M, Tanaka M. Spontaneous Regression of Polyposis following Abdominal Colectomy and Helicobacter pylori Eradication for Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2013;7:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, Peng T. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of a rare case and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520922427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seshadri D, Karagiorgos N, Hyser MJ. A case of cronkhite-Canada syndrome and a review of gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:197-201. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Yasuda T, Ueda T, Matsumoto I, Shirasaka D, Nakajima T, Sawa H, Shinzeki M, Kim Y, Fujino Y, Kuroda Y. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting as recurrent severe acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:570-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sampson JE, Harmon ML, Cushman M, Krawitt EL. Corticosteroid-responsive Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated by thrombosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1137-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nagata J, Kijima H, Hasumi K, Suzuki T, Shirai T, Mine T. Adenocarcinoma and multiple adenomas of the large intestine, associated with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:434-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yashiro M, Kobayashi H, Kubo N, Nishiguchi Y, Wakasa K, Hirakawa K. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome containing colon cancer and serrated adenoma lesions. Digestion. 2004;69:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chakrabarti S. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome (CCS)-A Rare Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:OD08-OD09. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Stanich PP, Lujan G, Hosmer A. Nausea and Diarrhea with Fingernail and Hair Changes. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:e7-e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jiang CD, Myint H, Tie A, Stace NH. Sustained clinical response to infliximab in refractory Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Matsuda S, Yoshinami N, Motoyoshi T. A Rare Case of Colonic Intussusception in an Adult. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:26-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Poulsen A, Nielsen MF. [Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is a rare polyposis syndrome]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2012;174:1612-1613. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Kobori I, Katayama Y, Suzuki Y, Yamaguchi M, Funada K, Gyotoku Y, Fujimoto Y, Shirahasi R, Kusano Y, Ban S, Tamano M. A case of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer associated with Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021;14:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |